Abstract

Difficulties associated with long term culture of primary trophoblasts have proven to be a major hurdle in their functional characterization. In order to circumvent this issue, several model cell lines have been established over many years using a variety of different approaches. These include lines derived from gestational tumors, or transformation/immortalization of primary trophoblast cells. Due to their differing origins, gene expression profiles, and behavior in vitro, different model lines have been utilized to investigate specific aspects of trophoblast biology. However, generally speaking, the molecular mechanisms underlying functional differences remain unclear. In this study, we profiled genome-scale DNA methylation in primary first trimester trophoblast cells and seven commonly used trophoblast-derived cell lines in an attempt to identify functional pathways differentially regulated by epigenetic modification in these cells. We identified a general increase in DNA promoter methylation levels in four choriocarcinoma (CCA)-derived lines and transformed HTR-8/SVneo cells, including hypermethylation of several genes regularly seen in human cancers, while other differences in methylation were noted in genes linked to immune responsiveness, cell morphology, development and migration across the different cell populations. Interestingly, CCA-derived lines show an overall methylation profile more similar to unrelated solid cancers than to untransformed trophoblasts, highlighting the role of aberrant DNA methylation in CCA development and/or long term culturing. Comparison of DNA methylation and gene expression in CCA lines and cytotrophoblasts revealed a significant contribution of DNA methylation to overall expression profile, most likely underlying functional variation between cells of different origin. These data highlight the variability in epigenetic state between primary trophoblasts and cell models in pathways underpinning a wide range of cell functions, providing valuable candidate pathways for future functional investigation in different cell populations. This study also confirms the need for caution in the interpretation of data generated from manipulation of such pathways in vitro.

Keywords: placenta, trophoblast, cell line, DNA methylation, epigenetics

INTRODUCTION

The human placenta is a temporary extra-embryonic organ that facilitates the exchange of nutrients and waste between the mother and fetus (Gauster et al. , 2009). It is heterogeneous in nature, comprising several cell types including trophoblasts (derived from the trophectoderm), mesenchymal cells (extra-embryonic and embryonic in origin), stromal fibroblasts and connective tissue, amongst others.

The trophoblast population is composed of three distinct cell types - stem-cell like villous cytotrophoblasts (CTBs), a multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast (ST) layer, and invasive extravillous cytotrophoblasts (EVTs) (Benerischke and Kaufmann, 2006). Each of these has specialized functions, important for proper placental and fetal development. Not surprisingly, cells of these different compartments display differences in morphology, function, and antigen and gene expression (Huppertz, 2008). Additionally, these populations differ in their expression of molecules involved in cell adhesion, proteases and their inhibitors, cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and receptors, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules (reviewed in (Hannan et al. , 2010)). For example, CTBs do not express HLA-G, while EVTs express HLA-C, HLA-E and HLA-G, but not HLA-A and HLA-B or HLA-DR (Apps et al. , 2009).

A variety of approaches are available for isolating specific populations of primary trophoblast cells for functional characterization (Apps et al., 2009), (Aboagye-Mathiesen et al. , 1996, Caulfield et al. , 1992, James et al. , 2007, Loke et al. , 1989, Manoussaka et al. , 2005, Petroff et al. , 2006, Stenqvist et al. , 2008, Yeger et al. , 1989). Generally speaking, these are labor intensive and the resulting cells are suitable for only short term characterization of specific trophoblast function in vitro [discussed in (King et al. , 2000)]. Consequently trophoblast-derived cell lines have become an important tool for studying processes underlying placental development and function.

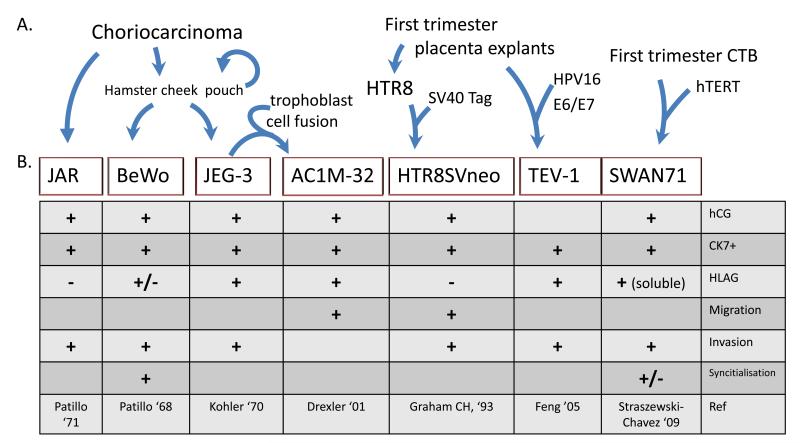

Each of the widely used trophoblast-derived cell lines has its own unique origin, functional characteristics and antigenic properties (Apps et al., 2009, Frank et al. , 2001, Hannan et al., 2010, King et al., 2000, Shiverick et al. , 2001, Sullivan, 2004) (Figure 1). In general terms, functions of the primary cells and tissues, from which they were derived, are at least partially replicated within cell lines, making them useful for dissecting mechanisms underlying specific trophoblast functions. Cell lines derived from gestational choriocarcinoma (CCA) were the first to be developed and have proven invaluable in studying trophoblast migration, as unlike many other tumor cells, some maintain their invasive potential in culture (Frank et al. , 1999). These cell lines have been in use for up to 40 years, and several choriocarcinoma and derivative trophoblast hybrid cell lines exist including JAR, JEG-3, BeWo and AC1M. JAR and JEG-3 lines are widely used to study molecular mechanisms underlying proliferation and invasive potential, while BeWo and AC1M-32 and -88 are commonly used to study processes underlying syncytialisation, and adhesion and migration, respectively (Figure 1) (Hannan et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Derivation and features of trophoblast cell models used in this study. A) JAR, BeWo, JEG-3, and AC1M-32 cell lines were all derived from primary choriocarcinoma tumour material, with (BeWo, JEG-3) or without (JAR) extensive repeated passaging (over several years) through hamster cheek pouches and cell fusion with primary placental trophoblasts (AC1M32). HTR8/SVneo and TEV-1 were derived from first trimester placental villous explants via transformation with Simian Virus -40 large T antigen (SV40Tag) or Human papilloma virus (HPV)-16 E6/E7 proteins, whereas SWAN-71 was derived by immortalisation of purified first trimester trophoblasts (CTB) with human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT). B) Features and utility of specific trophoblast cell line models. hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin, HLAG - human leukocyte antigen G.

Non-tumour derived placental cell lines have also been produced from primary placental tissue and cells using a range of transformation methods, including constitutive expression of telomerase (SWAN-71) (Aplin et al. , 2006), SV-40 large T antigen (HTR8/SVneo) (Graham et al. , 1993), and retroviral vector-mediated processes (TEV1) (Feng et al. , 2005). The SWAN-71 cells closely resemble EVTs in the expression of immunological antigens and growth factors, and the ability to invade matrigel (Aplin et al., 2006). The transformed HTR-8/SVneo cell line, derived from the cytotrophoblast-like HTR-8 cells, resembles EVTs when grown on matrigel (Graham et al., 1993). The TEV-1 cell line resembles EVTs in the expression of immunological antigens and phenotypic characteristics (Feng et al., 2005). Unlike the immortalized CCA cell lines, which have been cultured beyond 200 passages, some of the newer model lines show a lower proliferative capacity in culture, ranging from 10- [untransformed EVT-like HTR-8, SWAN-71], to over 100 passages (TEV-1).

In light of recent attempts to characterize genome-wide gene expression differences between trophoblast models (Burleigh et al. , 2007) and the unequivocal role of epigenetic variation in mediating changes in gene expression in cell function and development, including placental development and trophoblast function in animal and cell culture systems (Arima et al. , 2006, Li et al. , 1992, Rahnama et al. , 2006, Serman et al. , 2007, Vlahovic et al. , 1999), we aimed to profile genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in a wide range of trophoblast models with differing origins and functional capacities. Seven commonly used placental cell lines, TEV-1, HTR8/SVneo, SWAN-71, AC1M32, BeWo, JAR and JEG-3, were examined along with purified first trimester villous cytotrophoblasts (vCTB) and extravillous trophoblasts (EVT). Furthermore, we directly compared our methylation data to previously generated gene expression data in order to highlight the wide-ranging functional consequences associated methylation variation between different trophoblast populations.

METHODS

Purified primary trophoblast populations

Trophoblast cells were isolated as previously described (Tapia et al. , 2008) and purity of preparations determined using antibodies to the trophoblast-specific cytokeratin-7 (CK-7, 1:100 dilution, clone OV-TL 12/30, DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) or HLAG as previously described (Novakovic et al. , 2009). Only cell preparations in which 95% of the cells were positive for CK7 were used for subsequent experiments. In this study a combination of two independent villous CTB populations were pooled to produce one sample (863/864_vCTB). In addition, HLAG+ and HLAG− trophoblast cell populations were isolated from a further clinical sample. Freshly isolated trophoblast cells were stained with EGFR and HLA-G antibodies and the EGFR-HLAG+ (F58_EVTs) or EGFR+HLAG− (F58_vCTB) isolated by preparative FACS to >99% purity. These correspond to EVT and vCTB trophoblast populations respectively (Apps et al. , 2008). Ethical approval for the use of these tissues was obtained from the Local Research Ethics Committee.

Trophoblast-derived cell lines

JEG-3 (HTB-36; (Kohler and Bridson, 1971)) and JAR cells (HTB-144; (Pattillo et al. , 1971)) were maintained in RPMI-1640:10% FCS, BeWO (CCL-98; (Pattillo and Gey, 1968)) in Hams F12: 10% FCS and AC1M32 (Drexler et al. , 2001) in RPMI-1640:10% CS-FCS for 2–3 passages following thawing. Placenta-derived cell lines HTR-8/SVneo (Graham et al., 1993), SWAN-71 (Straszewski-Chavez et al. , 2009) and TEV-1 (Feng et al., 2005) were obtained from Drs C. Graham (Queen’s University, ON, Canada), G. Mor (Yale University, CT, USA) and H. Feng (University of Hong Kong, HK, China), respectively. These were cultured in RPMI-1640:5% FCS (HTR-8/SVneo), Hams F12/Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM):5% FCS:75 mM HEPES (TEV-1), or DMEM:10% FCS (SWAN-71) on plastic, fibronectin or laminin (Becton Dickinson). All cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 to approximately 80% confluence prior to harvesting for DNA extraction.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA samples were processed using the Methyl Easy™ bisulphite modification kit (Human Genetic Signatures, Sydney, Australia), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This process results in selective conversion of unmethylated cytosine nucleotides to uracil, thereby introducing a base-change in genomic DNA analogous to that seen with a SNP. This is detectable using appropriate bead-array technology with a single bead detecting either methylated or unmethylated sequences. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis was performed at the Australian Genome Research Facility (Melbourne, Australia). Infinium arrays were hybridized and scanned as per manufacturer’s instructions at Service XS (Leiden, The Netherlands). The arrays were background normalized in BeadStudio (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Individual probe β-values (range 0–1) were calculated in BeadStudio and are approximate representations of the absolute methylation percentage of specific CpG sites within the sample population. The values were derived by comparing the ratio of intensities between the methylated and unmethylated alleles using the following formula:

where Signal B is the array intensity value for the methylated allele and Signal A is the non-methylated allele. Any probe within a sample with a detection p value of 0.05 or greater was excluded from further analysis and recorded as an ‘NA’ (not analyzable) for that particular sample. Data analysis was carried out using the statistical programming language R with Bioconductor packages (Gentleman et al. , 2004). Heatmaps were generated using R language package gplots (cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/gplots.pdf).

Locus specific DNA methylation analysis was performed using the Sequenom EpiTYPER MaldiTOF technology as previously described (Wong et al. , 2008). PCR primers are listed in Supplementary table 1.

Gene Ontology and Pathway analysis

Our approach involved an initial interrogation of data sets with the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) application (Ingenuity® Systems, Redwood City, CA; www.ingenuity.com), followed by functional annotation using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (Dennis et al. , 2003, Huang da et al. , 2007). The IPA functional analysis identified molecular and cellular functions and disease-associated genes most significantly enriched in each of the data sets. The DAVID Ontology tool was used to determine the enrichment of individual gene ontology (GO) terms in each data set. Only ‘Biological process’ and ‘Molecular function’ GO terms, which showed significant enrichment (p <0.05), were reported.

Publicly available gene expression microarray data analysis

Gene expression data was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (Barrett and Edgar, 2006, Sayers et al. , 2009), (Database issue D885-D890). CEL files were downloaded from series GSE9973 (Bilban et al. , 2009) and GSE2531 (Burleigh et al., 2007) and processed with the bio-conductor package gcrma (Wu and Irizarry). The two expression matrices were merged based on probe ID as both were generated using the same array platform, the Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array. These comprised three samples of JEG-3, four of BeWo, isolates of primary EVT and five samples of vCTB. Gene expression data was then linked with the methylation data according to gene name. Sample quantiles were produced from the methylation data. The expression values of the genes in each quantile were then plotted as box and whisker plots.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

Infinium Methylation array data accurately reflects endogenous DNA methylation levels

A mixed purified population of CK7+ cytotrophoblasts (863/864_vCTB), and HLAG+ extravillous trophoblasts (F58_EVT) and HLAG− vCTB (F58_vCTB) fractions, both obtained from the same original vCTB population were available for methylation profiling in this study, along with seven commonly used trophoblast cell models, with different derivations (Figure 1). Validation of results obtained using methylation array analysis was carried out by Sequenom MassArray Epityping. Fourteen genes were tested in different cell lines. Methylation data was plotted where a single CpG site was interrogated by both Infinium and Sequenom platforms. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the correlation between Infinium and Sequenom (which approximates absolute % CpG methylation) for such assays. Pearsons correlation coefficient was 0.78, which is comparable or higher than that previously reported for similar comparisons (Katari et al. , 2009, Yuen et al. , 2009), and is equivalent in sensitivity to the corresponding correlation between bisulphite sequencing and Sequenom analysis, further supporting the utility of the Infinium platform.

Trophoblast cell lines differing in origin show variability in methylation levels and distribution

In order to obtain a single measure of overall DNA methylation in different trophoblast populations, we calculated a methylation index (MI) in a similar manner to that previously reported for Infinium methylation data (Bibikova et al. , 2009). MI represents the mean β-value of all Infinium probes for which β–values were obtained from all samples. In addition, we examined the distribution of MI relative to CpG density, by dividing probes into those located in annotated CpG islands (CGI-associated) and those that did not fall in these regions (non-CGI associated) according to Infinium annotation.

Interestingly, a gradient of MI was observed in CGI-associated methylation from non-transformed primary trophoblasts (MI=0.128 for F58_EVTs and MI=0.144 for F58_vCTB), to transformed trophoblasts (TEV-1, MI=0.181 and SWAN-71, MI=0.186) through to HTRA8/SVneo (MI=0.276) and CCA derived trophoblast models (MI=0.263 for JEG-3 and MI=0.306 for JAR cells) (Table 1). A smaller increase in average methylation relative to primary vCTB is also apparent in all cell models at the non-CGI Infinium probes, most likely due to the higher ‘basal’ methylation level at these CpG sites in the primary vCTB cells, relative to the CGI-associated sequences (Table 1). Thus, there is a selective increase in CGI-associated DNA methylation with transformation from primary trophoblasts to immortalized cellular models, supporting promoter methylation-induced gene silencing as a mechanism underlying the transformation process.

Table 1.

| CGI | non-CGI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average β value |

Fold increase c/f CTB |

Average β value |

Fold increase c/f CTB |

|

| Primary cells | ||||

| CTB | 0.134 | 1 | 0.459 | 1 |

| CTB (HLAG−) | 0.144 | 1.07 | 0.483 | 1.05 |

| EVT (HLAG+) | 0.128 | 0.955 | 0.377 | 0.82 |

| Cord blooda. | 0.185 | 1.38 | 0.612 | 1.33 |

| Trophoblast cell lines | ||||

| BeWo | 0.288 | 2.15 | 0.539 | 1.17 |

| JAR | 0.306 | 2.28 | 0.570 | 1.24 |

| JEG-3 | 0.263 | 1.96 | 0.512 | 1.12 |

| AC1M-32 | 0.271 | 2.02 | 0.466 | 1.10 |

| SWAN-71 | 0.186 | 1.39 | 0.538 | 1.17 |

| TEV-1 | 0.181 | 1.35 | 0.557 | 1.21 |

| HTR8/SVneo | 0.276 | 2.06 | 0.685 | 1.49 |

| Tumour lines | ||||

| REH-1 | 0.346 | 2.59 | 0.751 | 1.63 |

| MCF-7 | 0.224 | 1.67 | 0.547 | 1.19 |

| SW48 | 0.291 | 2.17 | 0.602 | 1.31 |

We also explored the distribution of this methylation in relation to the recently described age-associated differentially methylated regions (aDMRs). These are regions of the genome, recently identified as showing variable methylation over time (Rakyan et al. , 2010), primarily in non-CGI regions. When MI was examined in relation to aDMRs in trophoblasts and derived cell models, a clear enrichment of hypermethylation in these sequences was also apparent, consistent with their localization in primarily non-CGI genomic regions (Supplementary Figure 2)

In order to visualize the proportion of Infinium probes showing differential methylation between the three populations of primary cells and the seven placenta cell lines, each was plotted against all others using a scatter plot matrix (Supplementary Figure 3). As anticipated primary vCTBs (863/864_vCTB and F58_vCTB) and EVTs (F58_EVT) showed generally highly correlated methylation, while there was a trend towards hypermethylation of specific probe sets in AC1M32, BEWO, JAR, JEG-3 and HTR8/SVneo cell lines relative to primary cell counterparts (Supplementary Figure 3). This is in agreement with the increasing MI for these cell lines. Remarkably, very few probes showed a loss of methylation in the cell lines compared to primary trophoblasts, confirming that cellular transformation of trophoblasts in culture is associated with an excess of ‘gain of methylation’, rather than “loss of methylation” events at promoter regions.

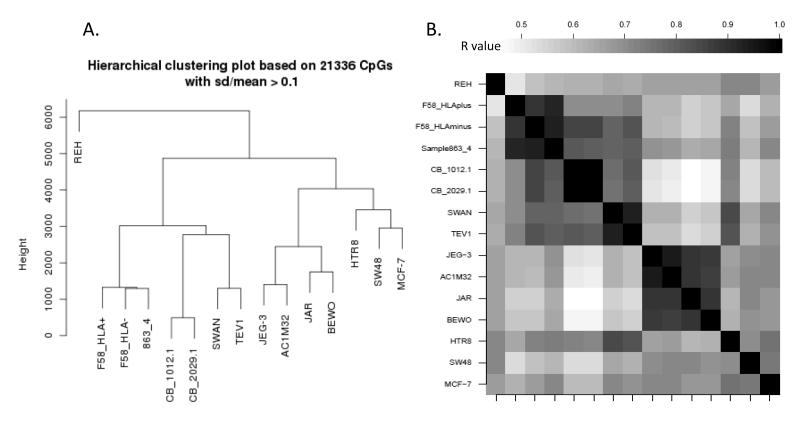

Epigenetic similarity between trophoblast cells is dependent on cell origin and degree of transformation

The overall relationship of methylation profiles of primary first trimester vCTBs and EVTs was compared to seven trophoblast-derived cell lines using unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis for Infinium probes showing a coefficient of variation greater than 0.1 (ie. most highly variable probes). To put the level of relatedness in context, we included data from primary cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMC), two solid cancer cell lines (SW48 and MCF-7), and one blood cancer cell line (REH) in the analysis (Figure 2A). The resulting relationships were based on their overall correlations (Figure 2B). Trophoblast-derived cells were found in two main branches. As expected the four CCA lines clustered together, away from primary CTBs and trophoblast-derived cell lines, other than HTRA8/SVneo (Figure 2A). Interestingly, TEV1 and SWAN-71 were most similar to each other despite their independent generation using differing methodologies and starting material (Figure 1), suggesting a common trophoblast origin. The HTR8/SVneo cell line clustered in the CCA branch but showed an overall methylation profile more similar to unrelated solid tumours (SV48 and MCF-7) than to the tumour-derived trophoblast models (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Relatedness of primary trophoblast DNA methylation profile to other cell lines. (A) Unsupervised Hierarchical Clustering of methylation data for all variable Infinium probes (sd/mean >0.1) highlighting the similarity in methylation profile of purified cytotrophoblasts 863_4 (863/4_vCTB), sorted HLAG+ EVTs (F58_HLA+), and HLAG- vCTB (F58_HLA-). SWAN-71 and TEV1 transformed trophoblasts cluster together as do non-transformed cord blood mononuclear cells (CB_1012.1 and CB_2029.1). Interestingly, the transformed HTRA8 SV/neo cell line clusters more closely with non-trophoblastic solid tumours SW48 (colon cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) than to either CCA-derived trophoblast lines, or other transformed trophoblast cells. All CCA-derived cells cluster together as anticipated. (B) Correlation plot of data used for cluster analysis. Note the clear distinction of the primary cell block comprising trophoblasts, cord blood and transformed SWAN and TEV1 cells.

The clustering of non transformed CBMCs with primary trophoblast cells and TEV1 and SWAN-71 in a separate branch from all other cells highlights the level of methylation changes associated with cancer-associated transformation and/or long term cell culturing, irrespective of tumour cell type. Conversely, the higher degree of clustering between the four CCA lines and the two solid cancer cell lines, implicates tumour-associated methylation as a driver of this groups relatedness. However, the HTR8/SVneo data suggest that the level of DNA methylation change associated with some non-tumourgenic cell models may be more extreme than in other lines.

We also examined the relationship between the CCA-derived lines and HTR8/SVneo further and showed a similar number of hypermethylated probes relative to primary trophoblasts in each case. Independent unsupervised clustering of the 1,217 most variable probes across these samples (>1.5 SD above the mean) revealed that only a minority of probes are methylated across all CCA lines and very few are commonly methylated between the CCA lines and HTR8/SVneo (Supplementary Figure 4). This suggests that a different set of genes were hypermethylated in the transformation process associated with HTR8/SVneo relative to the cancerous CCA lines.

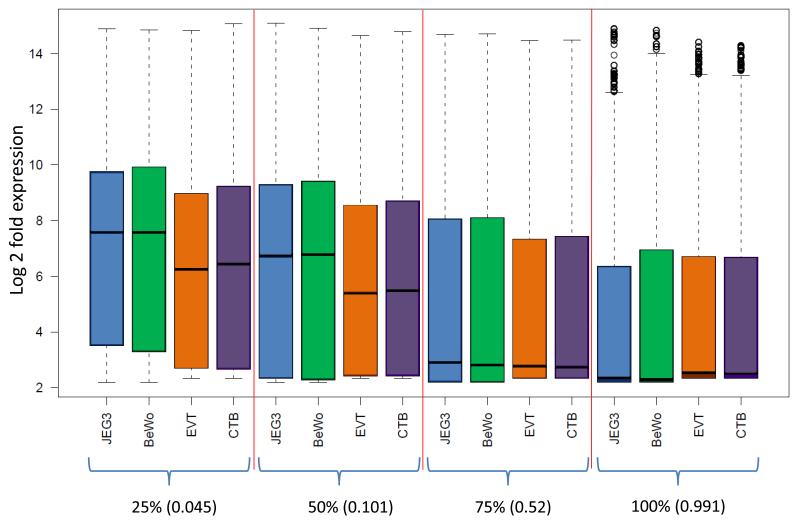

DNA methylation level is inversely correlated with gene expression in both primary trophoblasts and choriocarcinoma cell lines

In order to gauge the general effect of DNA methylation on associated gene expression level, Infinium probe methylation level in non-related primary vCTBs and EVTs, and two CCA lines (BeWO and JEG-3), was correlated with publically available expression data. Methylation probes were quantiled according to methylation, with mean β values of 0.044 (bottom 25% of probes), 0.102 (25-50%), 0.521 (50-75%) and 0.991 (top 25% of probes), and plotted against either individual sets of expression array data (Supplementary figure 5) or the mean of array data for specific cell populations (Figure 3). A general decrease in median expression level was seen for each of JEG-3, BeWo, EVT and vCTBs with increasing methylation level. In addition, there was a marked down regulation in median gene expression between the second (50%) to third quartiles (75%) associated with a change in mean methylation from 0.102 to 0.521. The inter-quartile range of expression levels was also lower in the upper two quartiles relative to the lower methylation quartiles (Figure 3), reflecting the variable expression of genes with low promoter methylation, and general silencing of genes with high promoter methylation levels. While intermediate levels of DNA methylation are not always associated with lower basal gene expression levels, they can play a major role in regulating the capacity for gene expression changes in response to stimuli. Therefore our ‘map’ of promoter methylation may inform future studies that measure the effects of exogenous stimuli on trophoblast cell function, by explaining variations in gene expression in response to treatment. For example, partially methylated genes may be less likely to respond to a stimulus relative to genes with a fully unmethylated promoter region.

Figure 3.

Relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression in trophoblast cell populations. Illumina BeadChip methylation data for JEG-3, BeWo, purified HLAG+ EVTs (F58_EVT) and purified vCTB (863/864 vCTB) was divided into quantiles according to probe numbers (ie. equal numbers of Infinium probes in each group). Mean methylation β-value for each group is shown in parentheses. These were then plotted (x-axis) against the corresponding gene expression values obtained from publicly available vCTB and EVT data (intensities; y-axis) in order to display the overall effect of increasing methylation on gene expression. This analysis clearly shows a decreasing median gene expression with increasing methylation, highlighting the functional relevance of DNA methylation in these cell lines.

Infinium probes hypermethylated in placental cell lines

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed to identify genes and pathways undergoing epigenetic silencing in placental cell lines of different origins. Probes with a β value >0.6 in each cell line were deemed to be ‘hypermethylated’ relative to CTB cells, provided the CTB β value was <0.2 (i.e. ≥0.4 β value increase). These stringent cut-offs were chosen to select methylation differences that are most likely to be biologically relevant (i.e. result in differential gene expression). The number of probes showing hypermethylation in each cell line is shown in Supplementary Table 2. CCA lines had between 1,461 (AC1M32) and 2,561 (JAR) probes showing hypermethylation compared to primary 363/64 CTBs, representing between 6-11% of all Infinium probes available for analysis. A large number of hypermethylated probes were also observed for HTR8/SVneo (1,509). Far fewer hypermethylated probes were apparent in SWAN-71 and TEV1, (357 and 279, respectively). Interestingly, while 1,012 probes (covering 749 genes; many genes have more than a single probe on the array) showed consistent hypermethylation across all CCA lines, only 347 (297 genes) were commonly methylated in HTR8/SVneo and CCA lines (Supplementary Figure 6). Furthermore, only 33 probes were hypermethylated across all 7 trophoblast models (Supplementary Table 2). A summary of the top Functions from Ingenuity Pathways and DAVID gene ontology analysis is shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 7, respectively. The results of this analysis reflect the similarity between probes hypermethylated in CCA lines.

The top Ingenuity Molecular and Cellular functions consistently hypermethylated in all choriocarcinomas and the HTR8/SVneo cell line were ‘cancer’, ‘cell movement’, ‘cell development’, and ‘cell growth and proliferation’, reflecting the highly proliferative nature of these cell lines, and the silencing of many tumour suppressor genes by promoter methylation (Supplementary Table 3). Similar genes are also selectively hypermethylated in CCA relative to SWAN-71 and TEV1 cells (230 cancer-associated genes). Conversely, 29 cancer-associated genes are commonly hypermethylated in SWAN-71 and TEV1 relative to CCAs, including the tumour suppressor E-cadherin, encoded by CDH1 (for which 4/7 probes show at least Δβ>0.2), which was also unmethylated in primary cytotrophoblasts. E-cadherin silencing is thought to increase proliferation, invasion, and/or metastasis in a variety of different human tumours (Berx and van Roy, 2009, van Roy and Berx, 2008).

Placenta-specific tumor-suppressor gene methylation is not always present in trophoblast cell lines

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) recognized 264 Cancer-associated genes (out of a total 643 genes in the IPA list), showing hypermethylation in all CCA lines and hypomethylation in CTBs (β<0.2), suggesting that the silencing of these genes is an aberration associated with choriocarcinoma development. However, recent studies have identified several cancer-associated genes that are selectively methylated in human placental tissue and primary trophoblast cells (Chiu et al. , 2007, Novakovic et al. , 2008). The role of this methylation in specifying specific aspects of placental function remains unclear.

We were interested in examining the methylation of several tumour-associated genes previously demonstrated to show increasing methylation in placental cell lines as a first step in understanding their potential involvement in specific aspects of trophoblast functioning. Differences in methylation of such genes were predicted to impact on functional characteristics of host cell lines. Table 2 lists the methylation levels of several published tumour-suppressor genes in vCTBs and the seven cell lines. Interestingly, several genes (APC, CD44, RASSF1 and KIAA0101), all previously shown to be monoallelically methylated in the placenta, were hypomethylated in all non-CCA derived trophoblast cell lines, and in the case of KIAA0101, also in the CCA lines. Given the roles of these genes as inhibitors of proliferation, migration and tumourogenesis, it is unclear why transformation should lead to a decrease in methylation levels at these sites. Despite these aberrations, the general trend in CCA is an increase in methylation of this class of genes, supporting a role for such methylation in specifying some of the ‘tumour-like properties’ of trophoblast cells (Ferretti et al. , 2007).

Table 2.

| Gene | vCTBs | AC1M | BeWo | JAR | JEG-3 | HTR-8 | SWAN | TEV-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| CD44 | 0.34 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| KIAA0101 | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| RASSF1 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.66 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| SFRP2 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| WIF1 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.41 |

| CDKN2A (p16) | 0.277 | 0.433 | 0.465 | 0.440 | 0.417 | 0.477 | 0.462 | 0.441 |

| EGR4 | 0.746 | 0.617 | 0.868 | 0.879 | 0.714 | 0.835 | 0.797 | 0.632 |

| SIM1 | 0.466 | 0.756 | 0.870 | 0.879 | 0.704 | 0.368 | 0.563 | 0.559 |

| DAB2IP | 0.645 | 0.812 | 0.882 | 0.869 | 0.836 | 0.360 | 0.220 | 0.389 |

Trophoblast cell lines show variation in epigenetic signatures at immune-related genes

Due to the differential expression of HLA markers in different placental cell lines, we sought to determine if these differences can be explained by DNA methylation (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary figure 8A). CTB cells show a range of methylation levels for the different HLA genes (0.04 for HLA-G to 0.64 for HLA-DRA), however, they do not express any of these HLA markers. Likewise for placental cell lines, DNA methylation level did not correspond with HLA expression patterns. One possible exception is the CCA cell line JEG-3, which showed high methylation for HLA markers that are not expressed in this cell line - HLA-A (0.68), HLA-B (0.8), HLA-DRA (0.76) and HLA-F (0.91), and lower methylation for HLA-C (0.28), HLA-E (0.54) and HLA-G (0.5), all of which are expressed in this cell line (r2 = 0.75). These data support the idea that a lower DNA methylation is associated with a potential for gene expression, whereas a high level of methylation is not generally compatible with either basal or inducible gene expression. However it is clear that the lower methylation of the specific sites in cells such as primary vCTB is not sufficient in itself to drive expression of genes such as HLA-C.

Further analysis of genes involved in regulation of immune response (GO term: 0050776), revealed 40 immune regulators with differential methylation in different cell lines (Supplementary figure 8B). Specific genes showing differential methylation between CCA and primary vCTBs in at least 2 probes include SYK (7 probes), TNF, CD40, STAT5B, CR1, IL15, TLR2 and RBP4. The consequences of such differential methylation on immune regulatory properties and antigen expression will require further investigation.

A role for altered DNA methylation in regulating hCG?

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is a hormone produced by the syncitiotrophoblast layer and secreted into the maternal compartment. It is also expressed more highly in EVTs than villous CTBs. Choriocarcinomas (such as those used to generate CCA cell models) are epithelial tumors which produce hCG (Seckl et al. , 2010). In this study, we found that the hCG α-subunit gene promoter shows approximately equal methylation in all trophoblast cell lines tested. However, that of the β-subunit gene differed between cell populations. CGB5 and 8, which make up 60-80% of total hCG-β transcripts (Uuskula et al. , 2010), show low methylation in primary vCTBs (mean β=0.28) and almost no methylation in EVTs (mean β=0.054), consistent with the elevated expression of hCG in EVTs relative to CTBs (Handschuh et al. , 2007). Increasingly higher methylation of these genes was seen in CCA lines (mean β=0.44) and transformed SWAN-71, TEV1 and HTR8/SVneo cells (mean β=0.76). CGB1 and CGB2 variants also show low methylation in primary EVTs (mean β=0.24), vCTBs (mean β=0.42) and CCA lines (mean β=0.41), with higher methylation in TEV1, Swan-71 and HTR8/SVneo lines (mean β=0.83). (Supplementary Figure 9). This methylation pattern supports a model whereby hCG expression and/or inducibility will be higher in primary EVTs, vCTBs and CCA cell lines relative to transformed placental lines. Non-placental cancer cell lines (MCF7, REH, SW48) show high levels of methylation, raising the intriguing potential that hCG may contribute to the invasive potential of CCA lines and primary trophoblasts, but not other cancer cell lines. Further supporting this hypothesis, treatment of MCF7 cells with hCG results in decreased cell proliferation and invasive potential (Rao Ch et al. , 2004).

Trophoblast cell lines show variation in epigenetic signatures across several gene families

Unsupervised clustering of primary vCTBs, EVTs, seven trophoblast cell lines, CBMCs and human cancer cell lines, was performed using several different lists of genes, selected from the Gene Ontology database (http://www.geneontology.org/). Classes of genes analysed included ‘Homeobox genes’, ‘negative regulators of migration’, negative regulators of cell cycle’, ‘inhibitors of canonical Wnt signalling’ and ‘regulators of immune response’, and were chosen due to their potential roles in proper trophoblast function. Clustering based on any of these groups resulted in the separation of primary vCTBs, CBMCs and SWAN-71 and TEV1 cell lines from Choriocarcinoma lines (Supplementary figure 8B-F). Analysis of ‘inhibitors of Wnt signalling’ supports published data, and visually shows that APC, SFRP1, SFRP2, and SOX2 are unmethylated in CBMCs, show higher methylation in cytotrophoblasts, and complete methylation in CCA lines (Supplementary figure 8F). Our analysis revealed differences between primary cells and CCA lines across several gene families and genes involved in specific pathways. This suggests that the large-scale differences in DNA methylation between vCTBs and CCA lines are not limited to a specific group of genes, but affect genes involved in many different aspects of trophoblast cell function.

Concluding comments

In this study we have revealed the wide-ranging and functionally relevant differences in DNA methylation profile that exist between primary human trophoblasts and derived cell models. At present it is unclear which of these differences are due to the variable starting material (eg. tumour vs non tumour), transformation process, or cell culturing factors (media, cell culturing), or a combination of all 3 factors. Irrespective of this, the extent of epigenetic differences and the proven role of epigenetic modification in regulation of gene expression and therefore cell morphology and function, is anticipated to impart profound functional differences on the cell models relative to their primary trophoblast counterparts. The classes of genes shown to be selectively altered need to be considered in the interpretation of functional data obtained in such systems, supporting replication of findings in primary cell populations wherever possible. Conversely, further analysis of differentially methylated pathways identified in this study in cell models with different functional capacities, offers tremendous opportunities to identify candidate genes involved in specific aspects of trophoblast function and capacity. Finally, as changes in DNA methylation alone cannot fully explain all of the known expression differences between cell models, there is a need for investigation of other epigenetic processes in trophoblast cells.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Correlation between Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip and Sequenom locus-specific methylation analysis. Methylation levels in 14 genes were assessed using Sequenom MassARRAY Epityping spanning specific CpG sites interrogated on the Infinium BeadChip Arrays. Correlation between platforms was 0.78 supporting the use of the Infinium system for profiling DNA methylation in this study. Genes interrogated were MX1, RARb, TNFRSF10A, TNFRSF10B, DUSP1, GSTO1, ATOX1, GPX7, HIF3A, DAB2IP, RASSF4, RASSF5 TBC1D10C and ZMYND10.

Supplementary Figure 2. Box and whisker plots showing selective methylation of age-related differentially methylated probes in transformed and tumour-derived trophoblast cell lines. Distribution of normalised Infinium β-values for cells used in this study is plotted on the y-axis. A) All probes for which data was obtained in all cell lines; B) distribution of aDMR methylation levels; C) distribution of CGI-associated Infinium methylation levels.

Supplementary Figure 3. Correlation plots showing degree of relatedness of all trophoblast-cells used in this study. A conditional scatter plot matrix of hexagonally binned trophoblast cell data, as implemented in the R package hexbin (hexbin: Hexagonal Binning Routines. R package version 1.22.0). Each scatterplot is comprised of a 20 × 20 matrix of hexagon bins. Count values are displayed as a colour gradient running from white (low count) to red (high count) on a perceptually linear scale. Green represents intermediate count number. Red boxed areas reflect cell populations showing highly correlated DNA methylation profiles.

Supplementary Figure 4. Unsupervised Hierarchical clustering of most highly variable Infinium methylation probes. Very few probes are commonly methylated between HTRA8/SVneo and other cell lines. CCA cell lines show some probes commonly methylated in all instances, while SWAN-71, TEV1 and HTR8/SVneo share a separate group of commonly methylated probes.

Supplementary Figure 5. Relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression level in primary trophoblasts and trophoblast-derived cell model lines. Expression values for individual samples are plotted on the y-axis against average quartiled DNA methylation levels for the same cell type (although not the identical isolate).

Supplementary Figure 6. Venn diagrams of genes showing hypermethylation (β>0.6) across several cell lines compared to primary vCTBs (β<0.2). Each CCA line had over 1,100 hypermethylated probes, of which 749 were hypermethylated in every CCA line, reflecting a co-ordinated hypermethylation of genes potentially associated with tumour progression. Of these, 297 probes were also hypermethylated in HTR8/SVneo cells (an intermediate cell line, showing some DNA methylation similarity to human cancers). In contrast, only 143 probes were hypermethylated in both SWAN-71 and TEV1 lines, and only 33 were hypermethylated in all 7 cell lines (AC1M32, BEWO, JAR, JEG-3, HTR8/SVneo, SWAN-71 and TEV-1).

Supplementary Figure 7. DAVID Gene Ontology analysis of top ranking ‘Molecular Functions’ in Choriocarcinoma cell lines, as a percentage of the total number of genes used for Ontology analysis. Ion binding, DNA binding, and transcriptional factor activity account for 55-58% of all hypermethylated genes in CCA. This reflects the similarity of probes showing hypermethylation in CCA lines. Furthermore, none of these three Molecular Functions were enriched in HTR8/SVneo, SWAN or TEV-1 cell lines (data not shown).

Supplementary Figure 8. Unsupervised clustering of samples based on specific gene ontology lists. A) HLA markers, B) Regulators of immune response, C) Negative regulators of migration, D) Negative regulators of cell cycle, E) Homeobox genes, F) Inhibitors of canonical Wnt signalling. Genes on the ‘Gene ontology’ list, which did not appear in the Infinium HumanMethylation27 array gene list, were not used for the clustering. Cell types are plotted on the X axis, and probes on the Y axis. White corresponds to 0% methylation and black to 100% methylation.

Supplementary Figure. Variable methylation of hCG promoters in trophoblasts of different origins. Clustering of samples based on hCG gene probe methylation levels. Cell types are plotted on the X axis, and specific transcript associated probes on the Y axis. White corresponds to 0% methylation and black to 100% methylation.

References

- Aboagye-Mathiesen G, Laugesen J, Zdravkovic M, Ebbesen P. Isolation and characterization of human placental trophoblast subpopulations from first-trimester chorionic villi. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:14–22. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.1.14-22.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin JD, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Kalionis B, Dunk C, Morrish D, Forbes K, Baczyk D, Rote N, Malassine A, Knofler M. Trophoblast differentiation: progenitor cells, fusion and migration -- a workshop report. Placenta. 2006;27(Suppl A):S141–3. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apps R, Gardner L, Hiby SE, Sharkey AM, Moffett A. Conformation of human leucocyte antigen-C molecules at the surface of human trophoblast cells. Immunology. 2008;124:322–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apps R, Murphy SP, Fernando R, Gardner L, Ahad T, Moffett A. Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) expression of primary trophoblast cells and placental cell lines, determined using single antigen beads to characterize allotype specificities of anti-HLA antibodies. Immunology. 2009;127:26–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima T, Hata K, Tanaka S, Kusumi M, Li E, Kato K, Shiota K, Sasaki H, Wake N. Loss of the maternal imprint in Dnmt3Lmat-/- mice leads to a differentiation defect in the extraembryonic tissue. Developmental biology. 2006;297:361–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Edgar R. Gene expression omnibus: microarray data storage, submission, retrieval, and analysis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:352–69. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benerischke K, Kaufmann P. Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, van Roy F. Involvement of members of the cadherin superfamily in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a003129. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibikova M, Le J, Barnes B, Saedinia-Melnyk S, Zhou L, Shen R, Gunderson KL. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling using Infinium assay. Epigenomics. 2009;1:177–200. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilban M, Haslinger P, Prast J, Klinglmuller F, Woelfel T, Haider S, Sachs A, Otterbein LE, Desoye G, Hiden U, et al. Identification of novel trophoblast invasion-related genes: heme oxygenase-1 controls motility via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1000–13. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh DW, Kendziorski CM, Choi YJ, Grindle KM, Grendell RL, Magness RR, Golos TG. Microarray analysis of BeWo and JEG3 trophoblast cell lines: identification of differentially expressed transcripts. Placenta. 2007;28:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield JJ, Sargent IL, Ferry BL, Starkey PM, Redman CW. Isolation and characterisation of a subpopulation of human chorionic cytotrophoblast using a monoclonal anti-trophoblast antibody (NDOG2) in flow cytometry. J Reprod Immunol. 1992;21:71–85. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(92)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu RW, Chim SS, Wong IH, Wong CS, Lee WS, To KF, Tong JH, Yuen RK, Shum AS, Chan JK, et al. Hypermethylation of RASSF1A in human and rhesus placentas. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:941–50. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Jr., Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler HGDW, MacLeod R, Quentmeier H, Steube KG, Uphoff CC, editors. DSMZ Catalogue of Human and Animal Cell Lines. DEutscher Sammlung Von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen; Braunschweig: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Feng HC, Choy MY, Deng W, Wong HL, Lau WM, Cheung AN, Ngan HY, Tsao SW. Establishment and characterization of a human first-trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line (TEV-1) J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:e21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti C, Bruni L, Dangles-Marie V, Pecking AP, Bellet D. Molecular circuits shared by placental and cancer cells, and their implications in the proliferative, invasive and migratory capacities of trophoblasts. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:121–41. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank HG, Funayama H, Gaus G, Schmitz U. Choriocarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid cells: reconstructing the pathway from normal to malignant trophoblast - Concept and perspectives: a Review. Placenta. 1999;20:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Frank HG, Morrish DW, Potgens A, Genbacev O, Kumpel B, Caniggia I. Cell culture models of human trophoblast: primary culture of trophoblast--a workshop report. Placenta. 2001;22(Suppl A):S107–9. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauster M, Moser G, Orendi K, Huppertz B. Factors involved in regulating trophoblast fusion: potential role in the development of preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30(Suppl A):S49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham CH, Hawley TS, Hawley RG, MacDougall JR, Kerbel RS, Khoo N, Lala PK. Establishment and characterization of first trimester human trophoblast cells with extended lifespan. Exp Cell Res. 1993;206:204–11. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschuh K, Guibourdenche J, Tsatsaris V, Guesnon M, Laurendeau I, Evain-Brion D, Fournier T. Human chorionic gonadotropin produced by the invasive trophoblast but not the villous trophoblast promotes cell invasion and is down-regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5011–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan NJ, Paiva P, Dimitriadis E, Salamonsen LA. Models for study of human embryo implantation: choice of cell lines? Biol Reprod. 2010;82:235–45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Collins JR, Alvord WG, Roayaei J, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. The DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R183. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B. The anatomy of the normal placenta. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1296–302. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.055277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JL, Stone PR, Chamley LW. The isolation and characterization of a population of extravillous trophoblast progenitors from first trimester human placenta. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2111–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katari S, Turan N, Bibikova M, Erinle O, Chalian R, Foster M, Gaughan JP, Coutifaris C, Sapienza C. DNA methylation and gene expression differences in children conceived in vitro or in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, Thomas L, Bischof P. Cell culture models of trophoblast II: trophoblast cell lines--a workshop report. Placenta. 2000;21(Suppl A):S113–9. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler PO, Bridson WE. Isolation of hormone-producing clonal lines of human choriocarcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971;32:683–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem-32-5-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke YW, Gardner L, Grabowska A. Isolation of human extravillous trophoblast cells by attachment to laminin-coated magnetic beads. Placenta. 1989;10:407–15. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(89)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoussaka MS, Jackson DJ, Lock RJ, Sooranna SR, Kumpel BM. Flow cytometric characterisation of cells of differing densities isolated from human term placentae and enrichment of villous trophoblast cells. Placenta. 2005;26:308–18. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic B, Rakyan V, Ng HK, Manuelpillai U, Dewi C, Wong NC, Morley R, Down T, Beck S, Craig JM, et al. Specific tumour-associated methylation in normal human term placenta and first-trimester cytotrophoblasts. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:547–54. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic B, Sibson M, Ng HK, Manuelpillai U, Rakyan V, Down T, Beck S, Fournier T, Evain-Brion D, Dimitriadis E, et al. Placenta-specific methylation of the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene: implications for feedback autoregulation of active vitamin D levels at the fetomaternal interface. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14838–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809542200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattillo RA, Gey GO. The establishment of a cell line of human hormone-synthesizing trophoblastic cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 1968;28:1231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattillo RA, Gey GO, Delfs E, Huang WY, Hause L, Garancis DJ, Knoth M, Amatruda J, Bertino J, Friesen HG, et al. The hormone-synthesizing trophoblastic cell in vitro: a model for cancer research and placental hormone synthesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1971;172:288–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb34942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff MG, Phillips TA, Ka H, Pace JL, Hunt JS. Isolation and culture of term human trophoblast cells. Methods Mol Med. 2006;121:203–17. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-983-4:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahnama F, Shafiei F, Gluckman PD, Mitchell MD, Lobie PE. Epigenetic regulation of human trophoblastic cell migration and invasion. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5275–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakyan VK, Down TA, Maslau S, Andrew T, Yang TP, Beyan H, Whittaker P, McCann OT, Finer S, Valdes AM, et al. Human aging-associated DNA hypermethylation occurs preferentially at bivalent chromatin domains. Genome research. 2010;20:434–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.103101.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Ch V, Li X, Manna SK, Lei ZM, Aggarwal BB. Human chorionic gonadotropin decreases proliferation and invasion of breast cancer MCF-7 cells by inhibiting NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25503–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Edgar R, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D5–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckl MJ, Savage PM, Hancock BW, Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, Lurain JR, Schink JC, Cagayan FM, Golfier F, Ngan H, et al. Hyperglycosylated hCG in the management of quiescent and chemorefractory gestational trophoblastic diseases. Gynecologic oncology. 2010;117:505–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.016. author reply 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serman L, Vlahovic M, Sijan M, Bulic-Jakus F, Serman A, Sincic N, Matijevic R, Juric-Lekic G, Katusic A. The impact of 5-azacytidine on placental weight, glycoprotein pattern and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in rat placenta. Placenta. 2007;28:803–11. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiverick KT, King A, Frank H, Whitley GS, Cartwright JE, Schneider H. Cell culture models of human trophoblast II: trophoblast cell lines--a workshop report. Placenta. 2001;22(Suppl A):S104–6. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenqvist AC, Chen T, Hedlund M, Dimova T, Nagaeva O, Kjellberg L, Innala E, Mincheva-Nilsson L. An efficient optimized method for isolation of villous trophoblast cells from human early pregnancy placenta suitable for functional and molecular studies. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straszewski-Chavez SL, Abrahams VM, Alvero AB, Aldo PB, Ma Y, Guller S, Romero R, Mor G. The isolation and characterization of a novel telomerase immortalized first trimester trophoblast cell line, Swan 71. Placenta. 2009;30:939–48. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MH. Endocrine cell lines from the placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;228:103–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia A, Salamonsen LA, Manuelpillai U, Dimitriadis E. Leukemia inhibitory factor promotes human first trimester extravillous trophoblast adhesion to extracellular matrix and secretion of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and -2. Hum Reprod. 2008 doi: 10.1093/humrep/den121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uuskula L, Rull K, Nagirnaja L, Laan M. Methylation Allelic Polymorphism (MAP) in Chorionic Gonadotropin {beta}5 (CGB5) and Its Association with Pregnancy Success. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Roy F, Berx G. The cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3756–88. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahovic M, Bulic-Jakus F, Juric-Lekic G, Fucic A, Maric S, Serman D. Changes in the placenta and in the rat embryo caused by the demethylating agent 5-azacytidine. The International journal of developmental biology. 1999;43:843–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong NC, Novakovic B, Weinrich B, Dewi C, Andronikos R, Sibson M, Macrae F, Morley R, Pertile MD, Craig JM, et al. Methylation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene in human placenta and hypermethylation in choriocarcinoma cells. Cancer letters. 2008;268:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JZ, Irizarry R. gcrma: Background Adjustment Using Sequence Information. R package version 2200.

- Yeger H, Lines LD, Wong PY, Silver MM. Enzymatic isolation of human trophoblast and culture on various substrates: comparison of first trimester with term trophoblast. Placenta. 1989;10:137–51. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(89)90036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen RK, Avila L, Penaherrera MS, von Dadelszen P, Lefebvre L, Kobor MS, Robinson WP. Human placental-specific epipolymorphism and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. PloS one. 2009;4:e7389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Correlation between Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip and Sequenom locus-specific methylation analysis. Methylation levels in 14 genes were assessed using Sequenom MassARRAY Epityping spanning specific CpG sites interrogated on the Infinium BeadChip Arrays. Correlation between platforms was 0.78 supporting the use of the Infinium system for profiling DNA methylation in this study. Genes interrogated were MX1, RARb, TNFRSF10A, TNFRSF10B, DUSP1, GSTO1, ATOX1, GPX7, HIF3A, DAB2IP, RASSF4, RASSF5 TBC1D10C and ZMYND10.

Supplementary Figure 2. Box and whisker plots showing selective methylation of age-related differentially methylated probes in transformed and tumour-derived trophoblast cell lines. Distribution of normalised Infinium β-values for cells used in this study is plotted on the y-axis. A) All probes for which data was obtained in all cell lines; B) distribution of aDMR methylation levels; C) distribution of CGI-associated Infinium methylation levels.

Supplementary Figure 3. Correlation plots showing degree of relatedness of all trophoblast-cells used in this study. A conditional scatter plot matrix of hexagonally binned trophoblast cell data, as implemented in the R package hexbin (hexbin: Hexagonal Binning Routines. R package version 1.22.0). Each scatterplot is comprised of a 20 × 20 matrix of hexagon bins. Count values are displayed as a colour gradient running from white (low count) to red (high count) on a perceptually linear scale. Green represents intermediate count number. Red boxed areas reflect cell populations showing highly correlated DNA methylation profiles.

Supplementary Figure 4. Unsupervised Hierarchical clustering of most highly variable Infinium methylation probes. Very few probes are commonly methylated between HTRA8/SVneo and other cell lines. CCA cell lines show some probes commonly methylated in all instances, while SWAN-71, TEV1 and HTR8/SVneo share a separate group of commonly methylated probes.

Supplementary Figure 5. Relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression level in primary trophoblasts and trophoblast-derived cell model lines. Expression values for individual samples are plotted on the y-axis against average quartiled DNA methylation levels for the same cell type (although not the identical isolate).

Supplementary Figure 6. Venn diagrams of genes showing hypermethylation (β>0.6) across several cell lines compared to primary vCTBs (β<0.2). Each CCA line had over 1,100 hypermethylated probes, of which 749 were hypermethylated in every CCA line, reflecting a co-ordinated hypermethylation of genes potentially associated with tumour progression. Of these, 297 probes were also hypermethylated in HTR8/SVneo cells (an intermediate cell line, showing some DNA methylation similarity to human cancers). In contrast, only 143 probes were hypermethylated in both SWAN-71 and TEV1 lines, and only 33 were hypermethylated in all 7 cell lines (AC1M32, BEWO, JAR, JEG-3, HTR8/SVneo, SWAN-71 and TEV-1).

Supplementary Figure 7. DAVID Gene Ontology analysis of top ranking ‘Molecular Functions’ in Choriocarcinoma cell lines, as a percentage of the total number of genes used for Ontology analysis. Ion binding, DNA binding, and transcriptional factor activity account for 55-58% of all hypermethylated genes in CCA. This reflects the similarity of probes showing hypermethylation in CCA lines. Furthermore, none of these three Molecular Functions were enriched in HTR8/SVneo, SWAN or TEV-1 cell lines (data not shown).

Supplementary Figure 8. Unsupervised clustering of samples based on specific gene ontology lists. A) HLA markers, B) Regulators of immune response, C) Negative regulators of migration, D) Negative regulators of cell cycle, E) Homeobox genes, F) Inhibitors of canonical Wnt signalling. Genes on the ‘Gene ontology’ list, which did not appear in the Infinium HumanMethylation27 array gene list, were not used for the clustering. Cell types are plotted on the X axis, and probes on the Y axis. White corresponds to 0% methylation and black to 100% methylation.

Supplementary Figure. Variable methylation of hCG promoters in trophoblasts of different origins. Clustering of samples based on hCG gene probe methylation levels. Cell types are plotted on the X axis, and specific transcript associated probes on the Y axis. White corresponds to 0% methylation and black to 100% methylation.