Abstract

Background

Long term survival for patients with AIDS-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is feasible in settings with available combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). However, given limited oncology resources, outcomes for AIDS-associated DLBCL in South Africa are unknown.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of survival in patients with newly diagnosed AIDS-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treated at a tertiary teaching hospital in Cape Town, South Africa with CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy (January 2004 until Dec 2010). HIV and lymphoma related prognostic factors were evaluated.

Results

36 patients evaluated; median age 37.3 years, 52.8% men, and 61.1% black South Africans. Median CD4 count 184 cells/μl (in 27.8% this was < 100 cells/μl), 80% high-risk according to the age-adjusted International Prognostic Index. Concurrent Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 25%. Two-year overall survival (OS) was 40.5% (median OS 10.5 months, 95%CI 6.5 – 31.8). ECOG performance status of 2 or more (25.4% versus 50.0%, p = 0.01) and poor response to cART (18.0% versus 53.9%, p = 0.03) predicted inferior 2-year OS. No difference in 2-year OS was demonstrated in patients co-infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (p = 0.87).

Conclusions

Two-year OS for patients with AIDS-related DLBCL treated with CHOP like regimens and cART is comparable to that seen in the US and Europe. Important factors effecting OS in AIDS-related DLBCL in South Africa include performance status at presentation and response to cART. Patients with co-morbid Mycobacterium tuberculosis or hepatitis B seropositivity appear to tolerate CHOP in our setting. Additional improvements in outcomes are likely possible.

Keywords: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, AIDS-related lymphoma, South-Africa, AIDS-related lymphoma risk score

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection increases the risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and other aggressive B-cell lymphomas1 and approximately 80% of AIDS-related lymphomas (ARL) are DLBCL.2 In South Africa, a large proportion of DLBCL are attributable to HIV. In Johannesburg, where HIV seroprevalence is >30%, 79.8% of DLBCL cases between Jan 2004 and Dec 2006 were HIV related.3 In the Western Cape, where HIV seroprevalence is approximately 15%, the Tygerberg Lymphoma Study Group noted a proportional increase in ARL from 6% to 37% between 2002-2009, despite large-scale roll out of combination antiretroviral treatment (cART) starting in 2004.4

The standard of care for DLBCL in patients not infected with HIV is CHOP (intravenous cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and oral prednisone)5,6 combined with the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab7 in settings where rituximab is available. For patients with AIDS, successful management of HIV with cART results in significant immune reconstitution, improves long-term outcomes and has allowed for evaluation of chemotherapeutic regimens for ARL. Several prospective studies have demonstrated dramatic improvement in outcomes in AIDS-related DLBCL compared to outcomes observed before the availability of cART.8-10 Chemotherapy regimens that have been evaluated include CHOP, and the continuous infusional regimens EPOCH (96 hour etoposide, doxorubicin, vincristine combined with prednisone and cyclophosphamide)11 and CDE (96 hour cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and etoposide).12 Each of these regimens has also been evaluated in combination with rituximab in patients with HIV.13,14 Although the combination of rituximab and CHOP is well established as first line treatment in HIV negative DLBCL, there remains equipoise regarding safety of rituximab in AIDS patients with CD4 counts <50 cells/μl.15,16

Implementation of regimens developed in the United States and Europe to address the increasing burden of HIV-associated DLBCL in South Africa’s public sector hospitals has been limited by lack of infrastructure to provide infusional regimens, lack of access to rituximab, and limited growth factors and other supportive care measures. As such, initial attempts to manage HIV-associated DLBCL in the setting of cART roll-out in South Africa has relied on CHOP as the most feasible treatment option. CHOP was the standard of care for nearly all patients with DLBCL treated at Tygerberg Hospital affiliated to Stellenbosch University in the Western Cape, South Africa. Outcomes in HIV positive patients treated with CHOP and cART appear comparable to outcomes in HIV negative patients receiving CHOP for DLBCL in some settings.9 However, given differences in infectious co-morbidities, differences in support care, and differences in health care delivery, outcomes using CHOP for the treatment of HIV-associated DLBCL in South Africa remains unknown. Furthermore, HIV specific risk factors may remain relevant for prognosis in AIDS-related DLBCL in South Africa. Given uncertainties regarding the optimal approach to treatment of HIV-related DLBCL in South Africa, we evaluated outcomes and prognostic factors17-19 in patients treated with the most commonly used regimen, CHOP or a CHOP-like regimen, during the period of early cART roll-out.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

We retrospectively analyzed all newly diagnosed DLBCL patients with documented HIV infection, treated with CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy at Tygerberg Hospital over 7 years (1st January 2004 until 31th December 2010). Clinical and therapeutic data were obtained from patient folders and laboratory data from the National Health Laboratory Service database. Deaths were identified by patient records and hospital databases. This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center Office for Human Research Protections, and complies with Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.20

Patient selection, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were identified by a Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) search of diagnostic codes for DLBCL on the electronic database containing histological, cytological and hematological data. Patients identified were reviewed for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) confirmation of HIV and histologically confirmed DLBCL. Only patients 15 years and older undergoing treatment with CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy were included.

Diagnosis, staging and risk assessment

Diagnosis and staging were based on standard-of-care practice at our institution. Lymph node and bone marrow histopathology and immunohistochemistry was supplemented by data from fine needle aspirations including flow cytometry. Results were reviewed by experienced histo- and hematopathologists. Diagnosis was made according to 2001 World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria.21 Where diagnostic uncertainty regarding possible Burkitt lymphoma existed, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis were performed to exclude MYC rearrangements (8q24) or translocation (8;14) fusion genes.22 No cases were sent for external review nor reclassified upon internal review.

Staging studies included physical exam, bone marrow trephine biopsy, and computerized axial tomography (CT), with stage determined using the Ann Arbor staging system modified at Cotswold.23 Patients with symptoms or signs suggesting central nervous system (CNS) involvement or involvement of high risk anatomical sites (paranasal sinuses, testis, orbit, bone marrow and bone)24 underwent lumbar puncture for cytopathologic evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid, as well as CT or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. Baseline evaluation of left ventricular ejection fraction was performed in all patients.

In patients with clinical and radiographic features suggestive of active Mycobacterium tuberculosis co-infection (TB), relevant samples were collected for microscopy and culture and when indicated, started antituberculous therapy. Serological evaluation for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) was performed on some patients prior to initiation of chemotherapy. Presence of the HBV surface antigen was regarded as HBV infected, and was managed using nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, lamivudine and tenofovir, agents with demonstrated activity against HBV, as part of cART. Presence of HBV surface antibodies without HBV surface antigen was regarded as immunity to HBV due to past infection as the national immunization schedule included HBV vaccination only since 1995.

Patient management and treatment

Patients were treated with CHOP consisting of cyclophosphamide (750mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), doxorubicin (50mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), vincristine (1.4mg/m2, max. 2mg intravenously on day 1) and prednisone (100mg orally) on days 1-5. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 45%, received the CHOP-like regimen CNOP, in which doxorubicin is substituted by an alternate anthracycline, mitoxantrone (8mg/m2 intravenously on day 1) to limit cardiotoxicity. For stage I or II, 4 cycles of chemotherapy was administered and for stage III-IV 6 to 8 cycles. Intrathecal chemoprophylaxis (methotrexate 12mg, cytarabine 30mg and dexamethasone 1mg) was given at every cycle of chemotherapy to all patients with either documented involvement or high risk of CNS involvement.

Precautions to minimize infective complications included antiseptic mouthwash and prophylactic antibiotics during the time of neutropenia. Growth factors (granulocyte colony stimulating factor, G-CSF) were not available for primary prophylaxis or to ensure that chemotherapy cycles could be given on time. Patients who progressed despite treatment or had a relapse after an initial response were subsequently treated with second line chemotherapies.

Patients not receiving cART at the time of diagnosis of DLBCL were referred to the Division of Infectious Diseases at Tygerberg Hospital to initiate cART, comprising primarily of stavudine, lamivudine and efavirenz, as soon as possible while receiving chemotherapy. Follow-up regarding cART was done at HIV clinics during and after completion of chemotherapy. Virologic suppression was evaluated according to the WHO treatment guidelines at 8-12 weeks after initiating therapy.25

Statistical analysis

Our primary objective was to document 2-year overall survival (OS) in South African patients with AIDS-related DLBCL treated with CHOP or CNOP at an academic institution using Kaplan-Meier methodology. Secondary objectives included evaluation of response rates, progression free survival (PFS) and prognostic factors for death. Individual prognostic factors evaluated included ECOG performance status, presence of extranodal disease, diagnosis of AIDS prior to diagnosis of DLBCL, CD4 count < 100 cells/μl, WHO defined virologic response to cART (sustained HIV viral load of < 200 RNA copies/ml), TB, sex and ethnicity. Patients were stratified by the International Prognostic Index (IPI),26 the age-adjusted (aa)IPI,27 and an AIDS-related lymphoma score, and these were evaluated in our setting.

Response to therapy was classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease or progressive disease (PD) according to the International Workshop criteria28 at three months, six months and twelve months after initiation of therapy. In patients achieving a CR, clinical follow up was generally done 3-monthly for two years then 6-monthly for two years then annually thereafter for a total of 5 years. OS was calculated from the time of DLBCL diagnosis, PFS was calculated as the time from DLBCL diagnosis to progression, relapse or death. Patients were censored at time of last clinical evaluation.

The log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions between the groups. Patient characteristics were compared between the groups with Chi-square or Fisher′s exact test in small sample situations. Differences between groups were regarded as significant for p values less than 0.05. Statistical evaluation was done in collaboration with the Centre for Statistical Consultation of Stellenbosch University.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

At Tygerberg Hospital, 281 cases of newly diagnosed DLBCL were identified 2004-2010. HIV serology was available in 60% of these cases diagnosed 2004 - 2006 compared to 81.9% diagnosed 2007 – 2010, when the availability of cART improved.29 Fifty (17.8%) patients were known to be HIV infected of which 14 (28%) were excluded from our analysis due to not receiving chemotherapy. Nine of these 14 died shortly after the initial diagnosis and 5 patients were lost to follow-up before starting treatment. Thirty six patients were treated with curative intent and included in the study Table 1. Nineteen (52.8%) patients were male, 17 (47.2%) female. Median age was 37 years (range 23 – 64), only 1 patient was older than 60. Twenty two (61.1%) were of black African and 14 (38.9%) of mixed ancestry.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical Features of 36 patients with AIDS-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

| Characteristics | Number (% or range) |

|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) | 35.5 (23-64) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 19 (52.8%) |

| Female | 17 (47.2%) |

| Race | |

| Black Africans | 22 (61.1%) |

| Mixed ancestry | 14 (38.9%) |

| Caucasians | 0 (0%) |

| Prior diagnosis of AIDS | |

| Yes | 21 (58.3%) |

| No | 15 (41.7%) |

| CD4 count at diagnosis | |

| MedianCD4 count (range) | 184 (28 – 2978) |

| Patients with CD4 count of < 100 cells/μl | 10/36 (27.8%) |

| ECOG Performance status | |

| 0-1 | 21 (58.3%) |

| ≥ 2 | 15 (41.7%) |

| Extranodal disease | |

| No | 8 (22.2%) |

| Yes | 28 (77.8%) |

| CNS involvement | |

| No | 30 (83.3%) |

| Yes | 6 (16.7%) |

| DLBCL Stage | |

| I | 1 (2.8%) |

| II | 4 (11.1%) |

| III | 3 (8.3%) |

| IV | 28 (77.8%) |

| International Prognostic Index (IPI)* | |

| 0 – 2 (Low / low-intermediate risk) | 17 (47.2%) |

| 3 – 5 (High-intermediate / high risk) | 19 (52.8%) |

| Age-adjusted IPI° (n = 35) | |

| 0 – 1 (Low / low-intermediate risk) | 7 (20.0%) |

| 2 – 3 (High-intermediate / high risk) | 28 (80.0%) |

| AIDS-related lymphoma risk score˜ | |

| 0 (Low risk) | 8 (22.2%) |

| 1 (Intermediate risk) | 16 (44.4%) |

| 2 (High risk) | 12 (33.3%) |

AIDS, Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; CNS, central nervous system

IPI, International Prognostic Index: a) Serum LDH above normal; b) Ann Arbor stage III or IV; c) ECOG performance status > 1; d) extranodal involvement > 1; e) Age > 60 years (1 point assigned for every adverse feature)26

Age-adjusted IPI: Includes all parameters as IPI with the exception of age (1 point assigned for every adverse feature)27

AIDS-related lymphoma risk score: a) IPI score 3 – 5; b) Prior diagnosis of AIDS excluding DLBCL as sole criterion for AIDS (1 point assigned for each feature)19

Twenty one (58.3%) had WHO stage IV disease (AIDS) prior to or at the time of diagnosis, not including AIDS-related DLBCL as the sole diagnostic criterion for AIDS. Median CD4 lymphocyte count at lymphoma diagnosis was 184 cells/μl (range 28 – 2978), 10 (27.8%) patients were severely immunocompromised defined as CD4 count < 100 cells/μl. Active TB was present in 9 of 36 (25.0%) patients; 7 had pulmonary and 2 had extrapulmonary disease as defined by the WHO criteria.30 Of 15 patients screened for Hepatitis B, 10 (66.7%) had serological evidence of prior exposure to Hepatitis B (HBsAb positive), which is similar to other urban HIV clinics in South Africa.31 Only 1 patient was HBV surface Ag positive with a detectable HBV viral load and was started on cART including tenofovir and lamivudine that effectively suppressed the replication of both viruses. No patients were seropositive for HCV. Additional co-morbidities and baseline complications of DLBCL were noted. Seven (19.4%) patients had renal dysfunction due to acute kidney injury from tumor lysis syndrome (3) or chronic kidney disease due to polycystic kidney disease, congenital single kidney with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis or focal proliferative glomerulonephritis (4). Lymphoma compressing the major airways, large blood vessels or spinal cord complicated the management of 4 (10.8%) patients.

Most patients (86.1%) had advanced DLBCL, 28 (77.8%) had stage IV and 3 (8.3%) stage III Table 1. Twenty eight (77.8%) had DLBCL involving extranodal sites of which 6 (16.7%) had CNS involvement. When classified according to the IPI26 19 (52.8%) patients had high-intermediate or high risk indices compared to 17 (47.2%) with low or low-intermediate risk indices. In the 35 of 36 patients <60 year-old, 28 (80.0 %) patients were classified as high-intermediate or high risk compared to 7 (20.0%) low or low-intermediate risk as classified by the aaIPI.27 By the AIDS-related lymphoma risk score,19 12 (33.3%) patients were classified as high risk, 16 (44.4%) intermediate risk and 8 (22.2%) as low risk.

Treatment

Thirty four patients (94.4%) received standard CHOP and 2 (5.6%) CNOP. A median of 5 cycles (range 1 – 10) of first line chemotherapy were administered. Fourteen (38.9%) patients completed planned 1st line therapy. Reasons for failure to complete 1st line therapy included 13 deaths (36.1%) occurring early during treatment, 5 (13.9%) progressive disease and 4 (11.1%) lost to follow-up. Early deaths were attributed to treatment-related complications (neutropenic sepsis and renal failure secondary to tumor lysis) in 6 cases, a direct consequence of lymphoma in 6. One outpatient died without a documented cause of death. Six patients received second line chemotherapy: 3 died due to progression of lymphoma despite chemotherapy, 2 had a complete response and 1 was lost to follow-up.

A total of 28 (77.8%) patients received cART during their treatment for DLBCL: 9 [median CD4 count 162 cells/μl (range 28 – 624)] were on cART at the time of diagnosis, 19 [median CD4 count 194 cells/μl (range 28 – 472)] were started during chemotherapy, and 8 [median CD4 count of 130 cells/μl (range 28 – 2978)] failed to start cART either due to early death or loss to follow-up. Virologic suppression was demonstrated in 6 (67%) patient on cART at baseline and 15 (79%) of patients initiated on cART during chemotherapy. In the 7 patients that did not achieve virologic suppression, 4 had documented poor adherence and 3 died within 8 – 12 weeks after initiation of cART before an assessment could be made.

Best response to treatment and survival outcomes

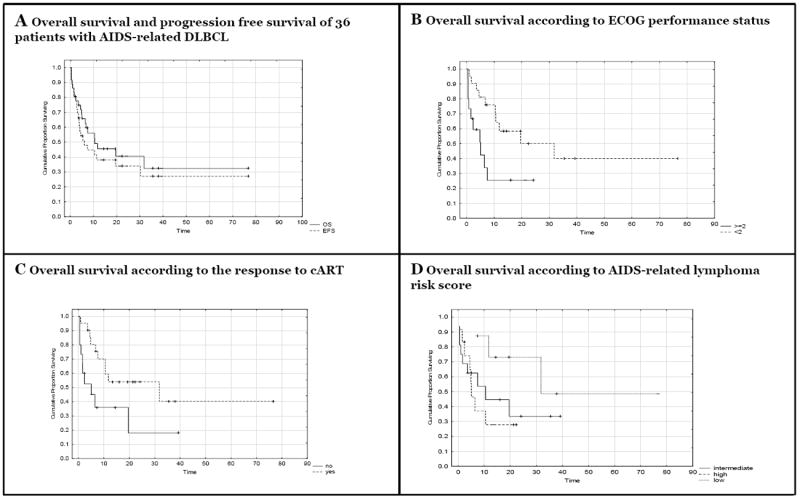

Twenty six (72.2%) patients had an objective response to chemotherapy. Fourteen (38.9%) achieved a CR with 1st line chemotherapy with 2 patients relapsing 3 and 6 months after completion of therapy. Twelve (33.3%) achieved a PR, of these 1 achieved CR with salvage therapy, 6 died (4 due to lymphoma, 1 due to renal failure and 1 due to sepsis) and 4 were lost to follow-up. One (2.8%) patient had primary PD and died despite salvage chemotherapy. Nine (25.0%) patients died early during treatment before response evaluation could be performed (4 due to lymphoma, 3 due to sepsis, 1 due to tumor lysis, and in 1 no documented cause could be identified). The patients’ response to CNOP was comparable to those that received CHOP: 1 achieved CR and relapsed 6 months after completion of therapy and 1 died within 1 month of initiation of treatment due to neutropenic sepsis. The estimated 2-year overall survival (OS) was 40.5%; median OS was 10.5 months (95% CI 6.5 –31.8), 2-year PFS was 34.0%; median PFS was 6.1 months (95% CI 3.8 – 30.3) Figure 1A.

Figure 1. A-D Survival outcomes of 36 patients with AIDS-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

A: 2-year OS was 40.5%; median survival was 10.5 months (95% CI 6.5 –31.8). 2-year PFS was 34.0%; median PFS time of 6.1 months (95% CI 3.8 – 30.3).

B: 2-year OS was 50.0% for ECOG score < 2 and 25.4% for ≥ 2 (p = 0.02).

C: Patients that had a response to cART showed significantly improved survival compared to those not responding (53.9% versus 18.0%; p = 0.03)25.

D: 2-year OS was 72.9% for low risk, 33.5% for intermediate risk and 27.8% for high risk (p = 0.18).

Median follow up period was 6.9 months. Patient follow up at 1 year: 13 out of 18 (72.2%) at 2 years: 9 out of 17 (52.9%) and at 3 years: 3 out of 16 (18.8%)

Prognostic factors and indices

The majority of our study population was <60 years-old (97.2%), presented with advanced stages of disease (86.1%) and had elevated LDH levels (91.7%). These individual factors were not prognostic. However, compared to subjects with an ECOG performance status of 0-1, those with an ECOG performance status of 2 or more had significantly worse 2-year OS (25.4% versus 50.0%, p = 0.02, Figure 1B) and PFS rate of 18.5% versus 43.7% (p = 0.01). When comparing the presence and absence of extranodal site involvement a non-significant trend towards a worse 2-year OS (33.9% versus 58.3%, p = 0.16) and PFS (30.6% versus 41.7%, p = 0.37) were observed in the group with extranodal involvement. Six (16.7%) patients had documented CNS involvement by DLBCL: 5 (83.3%) died due to lymphoma within 8 months of diagnosis with a median OS of 5.6 months (3 had a PR and 2 had primary PD); 1 patient with PR on 1st line chemotherapy achieved a CR after salvage therapy, and this patient was alive 15 months after completing therapy. Differences in survival between patients with and without CNS involvement were not statistically significant (p = 0.24, Table 2). An additional 7 patients deemed to be at high risk of CNS involvement received prophylactic IT chemotherapy with systemic chemotherapy. No documented cases of CNS relapse in these patients nor the low risk patients that did not receive IT chemoprophylaxis were identified. No differences in 2 year-OS were observed for sex (p = 0.72), ethnicity (p = 0.38) or TB co-infection (p = 0.87).

Table 2.

Prognostic factors for overall survival and progression-free survival in 36 patients with AIDS-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with CHOP or CHOP-like regimens

| Prognostic Factor | 2-year OS | p value | 2-year PFS | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 30.7% | 24.4% | ||

| Female | 45.3% | 0.72 | 41.2% | 0.37 |

| Race | ||||

| Black Africans | 29.8% | 24.5% | ||

| Mixed ancestry | 55.0% | 0.38 | 47.1% | 0.43 |

| Prior diagnosis of AIDS | ||||

| Yes | 30.1% | 27.3% | ||

| No | 56.6% | 0.31 | 44.0% | 0.54 |

| CD4 count at diagnosis | ||||

| ≥ 100 cells/μl | 48.0% | 38.9% | ||

| < 100 cells/μl | 22.9% | 0.10 | 22.9% | 0.27 |

| Virologic Response to cART | ||||

| Yes | 53.9% | 45.4% | ||

| No | 18% | 0.03 | 14.1% | 0.03 |

| ECOG Performance status | ||||

| 0-1 | 50.0% | 43.7% | ||

| ≥ 2 | 25.4% | 0.02 | 18.5% | 0.01 |

| CNS involvement | ||||

| Yes | 16.6% | 0.0% | ||

| No | 44.5% | 0.24 | 39.5% | 0.20 |

| Age-adjusted IPI | ||||

| 0 – 1 | 71.4% | 42.9% | ||

| 2 – 3 | 36.8% | 0.50 | 33.7% | 0.99 |

| AIDS-related lymphoma risk score | ||||

| Low risk | 72.9% | 62.5% | ||

| Intermediate risk | 33.5% | 24.6% | ||

| High risk | 27.8% | 0.18 | 27.8% | 0.24 |

OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; AIDS, Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index

A diagnosis of AIDS prior to the diagnosis of DLBCL did not have a significant impact on the OS or PFS (p = 0.31 and p = 0.54). Advanced stages of immunosuppression (CD4 count < 100 cells/μl) showed a trend for a worse OS but not PFS (p = 0.10 and 0.27 respectively) when compared to those with a CD4 count of ≥100 cells/μl. Patients achieving a favorable virological response to cART (as defined by WHO criteria) had statistically significant superior 2-year OS (53.9% versus 18.0%, p = 0.03) and PFS (45.4% versus 14.1%, p = 0.03 Figure 1C) compared to patients who did not. Outcomes with 1st line chemotherapy of patients on cART at the time of diagnosis (4 CR, 2 PR, 1PD, 4 deaths) and patients that started cART during chemotherapy (9 CR, 8 PR, 5 deaths, 2 lost to follow-up) were superior to those patients that failed to receive cART (1 CR, 5 deaths, 2 lost to follow-up). The median OS in the 3 groups were 6.93 months, 10.53 months and 1.03 months respectively.

Established indices for prognosticating survival in patients with DLBCL or AIDS-associated lymphoma could not be validated in this small cohort. Using the aaIPI, high / high-intermediate risk patients and a low / low-intermediate risk patients had a 2-year OS of 36.8% compared to 71.4% (p = 0.50) and PFS rates of 33.7% compared to 42.7% (p = 0.99). The large absolute differences in OS did not reach statistical significance most likely due to few low risk patients. The AIDS-related lymphoma risk score divided our patients in high, intermediate and low risk groups with 2-year OS rates of 27.8%, 33.5% and 72.9% (p = 0.18, Figure 1D) and 2 year PFS rates of 27.8%, 24.6% and 62.5% (p = 0.24) respectively.

Baseline factors that were significant (p < 0.05) or showed significant trends (p ≤ 0.1) in predicting 2-year OS in univariate analyses, ECOG performance score (< 2 versus ≥ 2), CD4 count (< 100 cells/μl versus ≥ 100 cells/μl) and virological response to cART (favorable versus unfavorable) were evaluated in an exploratory multivariate analysis, however none remained statistically significant independent predictors of death in this study (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Policies regarding public sector availability of cART have a large effect on the approach to diagnosing and treating AIDS-related DLBCL and other malignancies in South Africa. This retrospective study of HIV positive patients with DLBCL treated with standard chemotherapy (CHOP or CHOP-like regimens) at Tygerberg Hospital with curative intent from January 2004 until December 2010 is an early attempt to evaluate outcomes in this patient population when treated with CHOP. As noted in other studies of AIDS–related lymphomas, a majority of patients presented with stage III/IV disease.9,15,17-19,32 Additionally, 40% of patients in this study had an ECOG performance status of ≥2. Despite these high risk features and despite limited use of G-CSF, 2-year OS of 40% and 2-year PFS of 34% were comparable to other studies of CHOP from US and European centers.15,33

Besides demonstrating the feasibility of treating AIDS-related DLBCL is South Africa, our study evaluated several individual prognostic factors and indices. Both lymphoma-related and HIV-specific factors appear important in our setting. Poor performance status, generally attributed to lymphoma, was a significant risk factor for death. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed (baseline CD4 lymphocyte count< 100 cells/μl) had a 2-year OS of 22.9% compared to 48.0% (p = 0.10) for those with more preserved immunity (baseline CD4 lymphocyte count ≥ 100 cells/μl). Although the differences in outcomes did not reach statistical significance in our study, a clear trend towards a worse outcome is consistent with that seen in most studies of AIDS-related malignancies.17,26,34-36 On the other hand, response to cART was associated with improved OS and PFS.10,17 Importantly, a prior AIDS diagnosis or TB did not play a major role in the outcome of our patients. This was encouraging as TB is particularly important co-morbidity in our patient population. Importantly, 9 (25.0%) patients were diagnosed with and treated for active TB during the time they received treatment for lymphoma.

Although we used CHOP to treat AIDS-related DLBCL during this time period, other therapeutic regimens have demonstrated the potential to further improve lymphoma related outcomes in other settings. Treatment of HIV-negative DLBCL using rituximab (R), a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, in combination with CHOP (R-CHOP) resulted in improved survival outcomes compared to CHOP, but with a dramatic increase in costs.37,38 A randomized controlled trial of R-CHOP compared to CHOP in HIV positive patients did not demonstrate improved OS with the addition of rituximab, despite improved response rates, due to increase in infectious deaths in patients with low CD4 counts.22 However, subsequent studies suggest R-CHOP is safe and effective in a selected HIV-positive population.7 Furthermore, OS of 60% and progression free survival of 73% at 53 months has been demonstrated with the 96-hour infusional regimen dose-adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin).11 Subsequent published data on dose-adjusted EPOCH with the sequential or concurrent addition of rituximab reported a 2 year progression free survival (PFS) of 63 or 66% respectively and a 2 year OS of 67 or 70% respectively.13 However, significant cost related to infusion pumps, central lines and necessary G-CSF also make dose-adjusted EPOCH more difficult to implement in resource limited settings than CHOP.

Oral chemotherapy is desirable in resource limited setting. Mwanda et al. reported on their results of a prospective study evaluating dose-modified oral chemotherapy in patients with AIDS-related lymphomas in Kenya and Uganda.32 The overall response rate (ORR) (72.2%) and 2-year overall survival (40.5%) of CHOP for AIDS-related DLBCL in our study versus that of oral chemotherapy in patients with a range of AIDS-related lymphomas (documented ORR by intention-to-treat 64%, ORR in assessable patients 78%; estimated 2-year overall survival ~40%) were similar. However, comparison of these results should be interpreted with caution. On one hand, only 37% of patients in the East African study versus 77.8% in this series received cART during or immediately after completion of chemotherapy. On the other hand high-risk patients such as those with ECOG performance score of >3, patients that were not expected to survive 6 weeks and unacceptable end organ function, and those with CNS disease were excluded; patient selection led to treatment of 49 (32.9%) of a total of 149 patients with proven lymphoma and HIV infection in the Mwanda et al. study, compared to 36 of 50 (72%) of patients in our series. Furthermore, prospective clinical trials may benefit from close monitoring and follow-up that is not part of routine practice in resource limited settings. Further research on alternatives to CHOP is needed.

Our study adds to a growing body of evidence that cART significant improves OS in patients AIDS-related lymphoma in resource limited settings. cART improves outcomes in patients treated with either oral chemotherapy32 or those treated with CHOP.10 We further demonstrates that virologic suppression is associated with a significantly improved 2-year survival (53.9% versus 18.0%, p = 0.03).

Given the high burden of HIV infection and AIDS-related lymphoma in South Africa, curative intent approaches are urgently needed.39 Given current resource limitations, standard therapies for AIDS-related lymphoma that often include rituximab, G-CSF and/or infusional chemotherapy regimens, are currently not feasible at the scale needed to address the burden of disease, and further experience with oral regimens is required. Patients with diagnosed with DLBCL in South Africa should be tested for HIV, and those with AIDS-related DLBCL in should at least receive CHOP with appropriate supportive care. Improved therapy is needed for patients with CNS involvement, and clinical trials evaluating the safety and feasibility of implementation of other established therapies or novel approaches are urgently needed for the treatment of AIDS-related DLBCL in South Africa.

Despite our encouraging findings with CHOP and cART, it should be noted that a significant proportion of patients (28%) diagnosed with HIV-associated DLBCL at our institution never received treatment, mainly due to late presentation or loss to follow-up. Common reasons for delays in diagnosing lymphoproliferative disorders such as DLBCL include empiric use of anti-tuberculous treatment for lymphadenopathy in immunocompromised patients and limited access to existing speciality health care due in part to language barriers and lack of transportation. By the exclusion of these patients, our study population probably included a slightly more favorable risk group compared to the general patient population that presents with AIDS-related DLBCL to our institution. This might have resulted in more favorable survival outcomes than would otherwise be expected. Furthermore, of the patients treated for DLBCL in this study, HIV viral suppression was not achieved within the first 3 month of starting cART in 33% due to limitations in availability (8 patients, between 2004 and 2006), and poor drug adherence (4 patients). Additional strategies to improve the outcomes in HIV-associated DLBCL in South Africa may be possible through 1) testing all patients with DLBCL for HIV 2) further improving accessibility and adherence to cART for patients with AIDS-related malignancies 3) earlier diagnosis and treatment through community health care worker education, increased diagnostic capacity, and improved accessibility to referral hospitals and 4) identifying patients that would benefit most from more intensive supportive measures and closer follow-up using CD4 count, ECOG performance status, or established risk scores like the aaIPI and AIDS-related lymphoma risk score.

In conclusion, an estimated 34% of patients with AIDS-related DLBCL who initiated CHOP at Tygerberg Hospital were alive and lymphoma-free at 2 years. Patients with AIDS-related DLBCL in South Africa generally present with poor risk features including: high risk indices according to the aaIPI and advanced levels of immunosuppression (CD4 count < 100 cells/μl). Response to cART was an important factor influencing overall survival. Importantly, the high prevalence of co-infections in our population did not have a significant impact on outcome, demonstrating that lymphoma therapy can be integrated with antimicrobial therapy in this setting. Further improvements in the treatment of AIDS-related DLBCL in South Africa will likely require investment in infrastructure, access to affordable cancer drugs for treating AIDS-related malignancies in South Africa, as well as evaluation novel regimens within the setting of clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mr. Justin Harvey for the statistical analysis of the data and Prof. Judith Jacobson from Columbia University, NY.

Research Support

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Gucalp A, Noy A. Spectrum of HIV lymphoma 2009. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17(4):362–367. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328338f6b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sparano JA. HIV-associated lymphoma: The evidence for treating aggressively but with caution. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19(5):458–463. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282c8c835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantina H, Wiggill TM, Carmona S, Perner Y, Stevens WS. Characterization of lymphomas in a high prevalence HIV setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(5):656–660. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bf5544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abayomi EA, Somers A, Grewal R, et al. Impact of the HIV epidemic and anti-retroviral treatment policy on lymphoma incidence and subtypes seen in the western cape of south africa, 2002-2009: Preliminary findings of the tygerberg lymphoma study group. Transfus Apher Sci. 2011;44(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb JA, Gutterman JU, McCredie KB, Rodriguez V, Frei E., 3rd Chemotherapy of malignant lymphoma with adriamycin. Cancer Res. 1973;33(11):3024–3028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(14):1002–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304083281404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribera JM, Oriol A, Morgades M, et al. Safety and efficacy of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone and rituximab in patients with human immunodeficiency virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II trial. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(4):411–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine AM. Management of AIDS-related lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20(5):522–528. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283094ec7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarro JT, Lloveras N, Ribera JM, Oriol A, Mate JL, Feliu E. The prognosis of HIV-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and highly active antiretroviral therapy is similar to that of HIV-negative patients receiving chemotherapy. Haematologica. 2005;90(5):704–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bateganya MH, Stanaway J, Brentlinger PE, et al. Predictors of survival after a diagnosis of non-hodgkin lymphoma in a resource-limited setting: A retrospective study on the impact of HIV infection and its treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(4):312–319. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820c011a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little RF, Pittaluga S, Grant N, et al. Highly effective treatment of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma with dose-adjusted EPOCH: Impact of antiretroviral therapy suspension and tumor biology. Blood. 2003;101(12):4653–4659. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparano JA, Wiernik PH, Strack M, et al. Infusional cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and etoposide in HIV-related non-hodgkin’s lymphoma: A follow-up report of a highly active regimen. Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;14(3-4):263–271. doi: 10.3109/10428199409049677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparano JA, Lee JY, Kaplan LD, et al. Rituximab plus concurrent infusional EPOCH chemotherapy is highly effective in HIV-associated B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115(15):3008–3016. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-231613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tirelli U, Spina M, Jaeger U, et al. Infusional CDE with rituximab for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-hodgkin’s lymphoma: Preliminary results of a phase I/II study. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2002;159:149–153. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56352-2_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan LD, Lee JY, Ambinder RF, et al. Rituximab does not improve clinical outcome in a randomized phase 3 trial of CHOP with or without rituximab in patients with HIV-associated non-hodgkin lymphoma: AIDS-malignancies consortium trial 010. Blood. 2005;106(5):1538–1543. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabanillas F. Front-line management of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(6):642–645. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833ed848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann C, Wolf E, Fatkenheuer G, et al. Response to highly active antiretroviral therapy strongly predicts outcome in patients with AIDS-related lymphoma. AIDS. 2003;17(10):1521–1529. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miralles P, Berenguer J, Ribera JM, et al. Prognosis of AIDS-related systemic non-hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and highly active antiretroviral therapy depends exclusively on tumor-related factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(2):167–173. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802bb5d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka PY, Pracchia LF, Bellesso M, Chamone DA, Calore EE, Pereira J. A prognostic score for AIDS-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in brazil. Ann Hematol. 2010;89(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0761-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vollmann J, Winau R. Informed consent in human experimentation before the nuremberg code. BMJ. 1996;313(7070):1445–1449. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7070.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffe ES. Pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Vol. 3. Iarc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taub R, Kirsch I, Morton C, et al. Translocation of the c-myc gene into the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in human burkitt lymphoma and murine plasmacytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(24):7837–7841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowther D, Lister TA. The cotswolds report on the investigation and staging of hodgkin’s disease. Br J Cancer. 1990;62(4):551–552. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arkenau HT, Chong G, Cunningham D, et al. The role of intrathecal chemotherapy prophylaxis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):541–545. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2010. p. 156. 2010 revision ed. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A predictive model for aggressive non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. the international non-hodgkin’s lymphoma prognostic factors project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore DF, Jr, Cabanillas F. Overview of prognostic factors in non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998;12(10 Suppl 8):17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI sponsored international working group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosam A, Uldrick TS, Shaik F, Carrara H, Aboobaker J, Coovadia H. An evaluation of the early effects of a combination antiretroviral therapy programme on the management of AIDS-associated kaposi’s sarcoma in KwaZulu-natal, south africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(11):671–673. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: Guidelines for national programmes. 4. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2009. [2012]. p. 160. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241547833_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Firnhaber C, Reyneke A, Schulze D, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B co-infection in a south african urban government HIV clinic. S Afr Med J. 2008;98(7):541–544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mwanda WO, Orem J, Fu P, et al. Dose-modified oral chemotherapy in the treatment of AIDS-related non-hodgkin’s lymphoma in east africa. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3480–3488. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim ST, Karim R, Tulpule A, Nathwani BN, Levine AM. Prognostic factors in HIV-related diffuse large-cell lymphoma: Before versus after highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8477–8482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study group. Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, et al. Prognosis of HIV-associated non-hodgkin lymphoma in patients starting combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2009;23(15):2029–2037. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e531c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine AM, Sullivan-Halley J, Pike MC, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-related lymphoma. prognostic factors predictive of survival. Cancer. 1991;68(11):2466–2472. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911201)68:11<2466::aid-cncr2820681124>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiessard F, Morlat P, Marimoutou C, et al. Prognostic factors after non-hodgkin lymphoma in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: Aquitaine cohort, france, 1986-1997. groupe d’epidemiologie clinique du SIDA en aquitaine (GECSA) Cancer. 2000;88(7):1696–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: A randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(2):105–116. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: A study by the groupe d’etudes des lymphomes de l’adulte. Blood. 2010;116(12):2040–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sissolak G, Juritz J, Sissolak D, Wood L, Jacobs P. Lymphoma--emerging realities in sub-saharan africa. Transfus Apher Sci. 2010;42(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]