Abstract

Aim

The primary aim of this study is to compare survival to hospital discharge with a modified Rankin score (MRS) ≤3 between standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) plus an active impedance threshold device (ITD) versus standard CPR plus a sham ITD in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Secondary aims are to compare functional status and depression at discharge and at 3 and 6 months post discharge in survivors.

Materials and Methods

Design

Prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled, clinical trial.

Population

Patients with non-traumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treated by emergency medical services (EMS) providers.

Setting

EMS systems participating in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium.

Sample Size

Based on a one-sided significance level of 0.025, power = 0.90, a survival with MRS ≤ 3 to discharge rate of 5.33% with standard CPR and sham ITD, and two interim analyses, a maximum of 14,742 evaluable patients are needed to detect a 6.69% survival with MRS ≤ 3 to discharge with standard CPR and active ITD (1.36% absolute survival difference).

Conclusion

If the ITD demonstrates the hypothesized improvement in survival, it is estimated that2,700 deaths from cardiac arrest per year would be averted in North America alone.

Keywords: Cardiac arrest, sudden death, impedance threshold device, CPR

Introduction

Little is known about how to optimize resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. This is evident from the very low survival rates that are currently reported. (1-3) The advent of automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) and their potential for wide-spread use by less highly trained emergency medical service (EMS) providers and lay persons has not resulted in the substantial increased survival rates anticipated. (4) This has led to speculation that sooner and better circulation of oxygenated blood to the brain and heart may be important, even with AED availability.

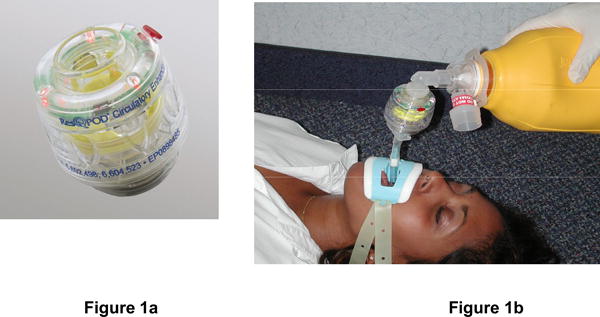

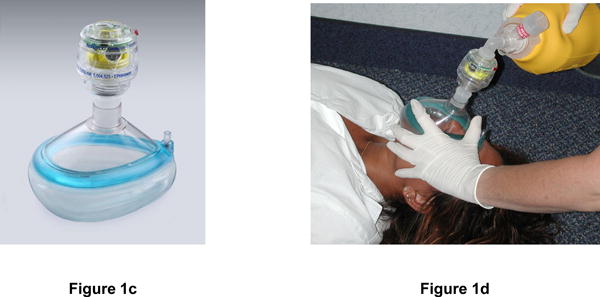

The Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) was created to evaluate the treatment of people with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest or life-threatening injury. (5) ROC is conducting a large randomized trial that uses a partial factorial design to test two strategies to increase blood flow during CPR. One strategy involves the impedance threshold device (ITD). (Figures 1a-d) This device enhances venous return and cardiac output by increasing the degree of negative intrathoracic pressure during decompression. It also increases coronary perfusion pressure so as to enhance delivery of oxygenated blood to the heart. The second strategy involves initiating resuscitation with a several minute period of manual compressions and ventilations before rhythm analysis (Analyze Later), rather than attempting defibrillation with a briefer period of manual compressions and ventilations (Analyze Early). Both strategies will be implemented concurrently in similar patient populations. The purpose of this paper is to describe the rationale and methods for the assessment of the impedance threshold device. The rationale and methods for the assessment of Analyze Later versus Analyze Early are described in a companion paper.

Figure 1. Description of Impedance Threshold Device.

The ITD (Figure 1a) is designed to be inserted easily between a facemask or advanced airway (e.g., ET tube, Combitube, or LMA) and a manual resuscitation bag (Figure 1b). In addition to an advanced airway, the ITD can be attached to any pediatric or adult facemask (Figure 1c) taking care to provide a continuously tight seal around the nose and mouth during compressions and ventilations (Figure 1d). As such, the device can be easily used by rescuers trained at both basic and advanced life support levels and moved quickly from any facemask once the patient is intubated. The ITD contains ventilation timing assist lights, which flash at 10/minute at 1 second/flash to help promote the proper ventilation rate and duration for the patient with an advanced airway. For this trial, ITDs will be specially manufactured in an opaque color so that active (functional) and sham (non-functional placebo) devices will appear externally identical.

Background and Significance

The ITD is based on the principle that creating a greater negative intrathoracic pressure on the upstroke of CPR leads to increased venous blood return to the heart and increased cardiac output. (6-19) Compared with standard CPR, improved hemodymanics with use of the ITD is dependent on the quality of CPR provided (20-26) and the degree of chest wall recoil. (27,28) This concept has been evaluated in animals (6,7,9-11,14,16,18) as well as in human patients with prolonged cardiac arrest undergoing standard manual CPR. (29-31)

The first controlled animal study of the ITD with standard CPR used a four-minute period of cardiac arrest followed by standard CPR with an automated compression device. (16) Standard CPR was performed with and without the ITD in an alternating fashion. Each time the ITD was removed from the respiratory circuit, the coronary perfusion pressures and vital organ perfusion decreased; each time the ITD was added back, perfusion pressures stabilized or increased.

A similar study evaluated active ITD versus sham ITD for 11 minutes after a six-minute period of cardiac arrest without CPR. (6) A sham ITD was used in the control group and an active ITD in the other. After 6 minutes of cardiac arrest and 6 minutes of standard CPR, radiolabeled microspheres were injected to measure vital organ blood flow. The active ITD increased left ventricular flow by 100%, and nearly normalized blood flow to the brain compared to the sham ITD. After a total of 17 minutes of ventricular fibrillation and 11 minutes of CPR, 3/11 pigs in the sham ITD group and 6/11 pigs in the active ITD group were resuscitated by direct current shock. In many ways, this six-minute arrest time prior to start of CPR more closely resembles clinical field experience where the time from arrest to the start of CPR in the United States ranges from 4-8 minutes in cities with highly efficient EMS systems.

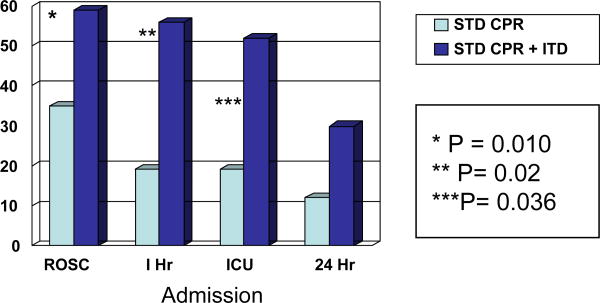

A recent human study randomized 230 adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to receive standard CPR and sham ITD versus standard CPR and active ITD. (29, 30) The primary outcome of this study was admittance to ICU. (29) Femoral arterial blood pressures were also evaluated during standard CPR at the scene in 22 other patients using the same protocol. (30)

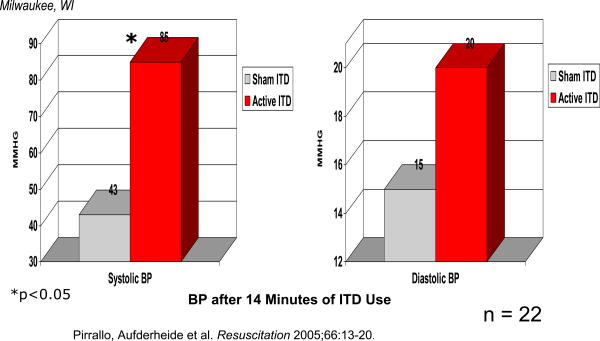

ICU admissions for all patients were not significantly different with use of the active ITD versus sham ITD (25% vs. 17%, respectively, P=NS). However, there were significantly increased ICU admissions in patients presenting in pulseless electrical activity (PEA) with use of active ITD, 19% (5 of 26) vs. 52% (14 of 27) (P = 0.02; not significant when corrected for comparisons in three rhythm groups-.05/3=.017). (Figure 2) In the hemodynamic study, systolic blood pressure was significantly increased with the active ITD versus the sham ITD: 85.1 ± 28.9 mmHg (n = 10) versus 42.9 ± 15.1 mmHg (n = 12), respectively; P < 0.001. (Figure 3)

Figure 2. Outcomes for Patients Presenting with PEA.

ROSC=Return of Spontaneous Circulation; 1 Hr=1-Hour Survival; ICU=ICU Admission Rate; 24 Hr=24 Hour Survival

Figure 3. Femoral Arterial Blood Pressure in Humans During CPR with ITD Use.

The ITD in combination with conventional manual CPR was evaluated in a case-control study in large EMS system in Staffordshire, England. (31) Survival to emergency department admittance was significantly greater among patients with any initial rhythm who received the ITD (61/181 [34%]) compared with historical controls (180/808 [22%]) (P<0.01). No device-related adverse effects were observed.

In summary, these studies demonstrate that the ITD improves hemodynamics and short-term outcomes. A large trial is now required to demonstrate whether the ITD significantly improves survival to hospital discharge and functional status.

Aims

The primary aim of the trial is to compare survival to hospital discharge with a modified Rankin score (MRS) ≤3 between standard CPR plus active ITD versus standard CPR plus sham ITD in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Secondary aims are to compare survival to discharge, functional status scores at discharge and at 1, 3 and 6 months as well as depression at 3 and 6 months between standard CPR plus active ITD versus standard CPR plus sham ITD in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study qualifies for waiver of consent in emergency research as outlined in the United States by FDA regulation 21CFR50.24 and in Canada by the Tri-Council Agreement for research in emergency health situations (Article 2.8).

This randomized trial will evaluate manual CPR with either an active or sham ITD in adult patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Randomization will occur through use of a study ITD that is constructed such that the sham and active valves are indistinguishable.

Study Episodes

Episodes attended by EMS will be included if a study device was taken from its sealed container. All such episodes will be followed for purposes of safety evaluation.

Study Population

Included will be persons aged 18 years or more (or local age of consent) who suffer non-traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest outside of the hospital in the study communities who receive defibrillation and/or chest compressions by EMS providers dispatched to the scene. The etiology will be presumed to be non-traumatic in origin unless the apparent cause is due to blunt, penetrating or burn related injury, drowning, strangulation, electrocution, or exsanguination.

Excluded will be persons with ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) orders; trauma; known prisoners; known pregnancy; persons bearing a designated indicator (e.g. bracelet) of their having “opted out” of the trial as required by local IRBs; tracheostomy; CPR performed with any mechanical compression device; ventilated with a mechanical device (e.g. automated transport ventilator); or initial treatment by a non-ROC EMS agency/provider with no agreement in place to obtain relevant EMS data.

Comparison Populations

The ITD is conjectured to provide an improvement in the rate of neurologically intact (MRS ≤ 3) survival to hospital discharge in those patients experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OOHCA) of cardiac origin and treated by EMS within 15 minutes of initial call to 911. There is, however, no known contraindication to the use of the ITD in the relatively few patients for whom the cardiac origin of OOHCA cannot be accurately determined, and such patients may be included in the clinical trial to contribute safety information.

Efficacy Population

Analysis of primary and secondary efficacy outcomes will be conducted on a modified intent-to-treat basis. In order to be included in these analyses, patients must meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the ITD/sham device intervention. Furthermore, they must have had a response time from call received at 911 dispatch to arrival at the scene of less than 15 minutes, and had the ITD actually applied.

Safety Population

Evaluation of the safety of the ITD will be made using all data from patients who were treated with a device, regardless of whether they are a member of the efficacy population.

Intervention

The intervention will be implemented by the first qualified provider to arrive at the scene of cardiac arrest and continued by subsequent providers in all ROC sites. Upon arrival of EMS providers at a patient with cardiac arrest, CPR will be initiated. Defibrillation will be performed consistent with local practice and cluster assignment (see companion paper). For subjects who are being ventilated with bag-mask or advanced airway (e.g., Combitube, laryngeal mask airway [LMA], or endotracheal tube), EMS providers will insert an ITD between the bag and the mask/airway. The ITD is constructed in a manner (male connection to the mask/airway or advanced airway, and female connection to the ventilation bag/apparatus) that prevents its proper orientation to the patient from being inadvertently reversed. Training will target use of the ITD with initial management of the airway to assure the earliest placement of the ITD during CPR. To assure correct ventilation rate, the rescuers will turn on the ventilation timing assist lights on the device once an advanced airway has been established. The providers will be instructed to immediately remove the ITD if the patient has return of spontaneous circulation or is breathing spontaneously (to facilitate rapid elimination of inspiratory impedance in a resuscitated patient). The study ITD has a safety check valve that opens if the pressure in the airway is <16 cm H2O in the event the rescuer does not recognize spontaneous respirations. The providers will be instructed to immediately reapply the ITD if such a patient has recurrent cardiac arrest.

If the ITD fills with fluid, the EMS providers will be instructed to disconnect the ITD, removing the fluid by forcing air through the device, suction the patient, and reapply the ITD. If the ITD fills with fluid a second time, the ITD will be permanently removed. Use of the ITD will be discontinued on arrival to the hospital. All other resuscitative measures will follow individual EMS agency standard operating procedures.

Random Allocation

Study devices will be randomly allocated in a proportion of 1:1 active vs. sham, with distribution determined by the coordinating center based on permuted blocks of concealed size within strata defined by participating site and within site by participating agency or subagency. Devices will be packaged with a flexible connector to facilitate adjunct equipment such as CO2 monitoring. A mask will also be provided to facilitate achievement of a good seal between the patient's face and the ventilatory circuit so as to maintain the intrathoracic pressure. Each ITD package will be identifiable by a coded number, which will be recorded on the emergency care record. Active and sham ITDs look identical. Patients will be considered randomized if the ITD package is opened. If two bags are opened during the arrest episode, the patient will be assigned to the treatment group of the bag opened by the first-arriving vehicle.

Training

The training objectives for the ITD study include: review of optimal CPR performance, scientific basis for and review of the study protocol, practicum/“hands-on” session, and post-test, requiring approximately 2 hours of didactic instruction and 1 hour of practicum. Supplemental web-based training materials will also be available for initial training or retraining. Some type of retraining will occur at least every 6 months. Initial and retraining performance criteria include: correct assembly of the airway, time to ITD application < 30 seconds, continuously tight seal maintained during compressions and ventilations when ITD is used with a facemask, ventilation timing lights turned on following placement of an advanced airway, immediate removal of ITD with return of spontaneous circulation, immediate reapplication of the ITD with re-arrest, and clear or remove ITD if it fills with fluid.

Run-in Phase

After personnel have been trained in use of the ITD, sites will initiate a run-in phase. Evidence of compliance with the protocol and completion and submission of the data will be required before the site can enroll in the active phase of the trial.

Monitoring Protocol Compliance

A monitoring committee will evaluate protocol compliance during the run-in and active phases of the trial. Guidelines include: ITDs should be placed on 90% of ITD eligible patients, interval from ROC-ITD vehicle arrival to placement of ITD is < 5 minutes for 90% of analyzable cases, providers should report a continuously tight facemask seal during compressions and ventilations when the ITD is used with a bag-valve-mask, and there should be no inappropriate enrollment or treatment of subjects. Compliance will be further monitored by tracking the incidence of not using the ITD with a facemask (ITD use with advanced airway only), opening a bag but not using the ITD, and opening more than one ITD bag/patient.

Performance of high quality CPR is considered essential to the success of any intervention during resuscitation. Accordingly, all participating EMS agencies have implemented a high-quality system for monitoring individual components of CPR, to include the rate of chest compressions, the rate of ventilation, and the proportion of pulseless resuscitation time during which chest compressions are provided (i.e. CPR fraction) as described in the companion paper.

Expected Adverse Events

The following will be considered adverse events if they occur during the resuscitative effort or the hospital stay:

Pulmonary Edema

The presence of pulmonary edema in patients who survive long enough to receive a hospital-based chest x-ray (first emergency department or ICU chest x-ray) will be evaluated. Because pulmonary congestion in the immediate aftermath of cardiac arrest is not an unexpected finding, its incidence will be monitored in each treatment arm. Similarly, in the out-of-hospital setting, all incidences where the valve fills with fluid will be reported.

Device Failure

Any instances of device malfunctions will be reported.

Other

Vomiting during CPR is a common and anticipated complication of any method of CPR and its occurrence will be monitored in each treatment arm. Clinical diagnoses of cerebral bleeding, stroke, seizures, bleeding requiring transfusion or surgical intervention, recurrent cardiac arrest, serious rib fractures, sternal fractures, internal thoracic or abdominal injuries as well as any other major medical or surgical outcomes will be collected from the hospital discharge summary.

Notably, death or neurological impairment of an individual patient is not considered an adverse event in this study.

Results

Primary

The primary analysis of treatment efficacy will be based on a comparison across treatment arms (active and sham ITD) of the observed proportion of patients in the efficacy population with neurologically intact (MRS ≤ 3) survival to hospital discharge.

Secondary

The secondary outcomes are MRS at 3 and 6 months following hospital discharge; Adult Lifestyle and Function (ALFI) version of the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) at 1, 3 and 6 months; (32, 33) as well as Health Utilities Index III (HUI3) score (34) and Geriatric Depression Scale (T-GDS) (35) score at 3 and 6 months.

All secondary analyses of efficacy outcomes are directed toward finding supporting evidence for the findings of the primary efficacy analysis. Hence, there is no plan to make any statistical adjustment for the multiple comparisons inherent in the secondary efficacy analyses.

In-Hospital Morbidity

Number of hospital days and time interval from 911 call to patient death will be described for all hospitalized patients as measures of morbidity after resuscitation.

Prespecified Subgroup Analyses

First recorded cardiac arrest rhythm prior to ITD application (VF/VT vs. PEA vs. asystole vs. not obtained before device implementation);

Observational status of arrest (witnessed by EMS vs. witnessed by bystanders vs. unwitnessed);

In witnessed cardiac arrests, response time interval from call to initiation of CPR by EMS (<10 vs. ≥ 10 minutes); (15)

Analyze Early vs. Analyze Later vs. not participating in these cohorts.

Analyses will be performed in each subgroup, along with tests for statistically significant interactions. However, it is recognized that the study is not powered adequately to detect interactions, and thus all subgroup analyses will be of an exploratory nature.

Sample Size and Study Duration

The potential benefit of the ITD to increase neurologically intact survival is hypothesized to vary according to presenting cardiac rhythm from 20.2% to 24.2% in VT/VF, from 4.20% to 5.88% in PEA, and from 1.05% to 1.47% in asystole. Any potential benefit of the ITD is hypothesized to be greatest when it is used as early as practicable, which might be prior to determination of the prior rhythm. The study is therefore powered to detect the differences that would be observed in a population that included 25% VT/VF, 25% PEA, and 50% asystole.

Based on a one-sided significance level of 0.025, power = 0.90, a survival with MRS < 3 to discharge rate of 5.32% with standard CPR and sham ITD, and two interim analyses, a maximum of 14,742 evaluable patients are needed to detect a 6.68% survival with MRS < 3 to discharge with standard CPR and active ITD (1.36% absolute survival difference). The study will require approximately 16-18 months of enrollment.

Conclusion

A large clinical trial is needed to determine the impact of the ITD on survival to hospital discharge and functional outcome for patients with cardiac arrest. Preliminary data indicates the ITD has potential to have substantial impact. If the ITD demonstrates the hypothesized improvement in survival, we estimate that the premature demise of approximately 2,700 victims of cardiac arrest1 per year would be averted in North America compared to standard CPR without use of the ITD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a cooperative agreement (5U01 HL077863) with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute in partnership with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) - Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Defense Research and Development Canada, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Footnotes

Number of treatable cardiac arrests × Proportion of cases with non VF initial rhythm or VF that does not respond to initial shock × Absolute difference in survival i.e. (US population 295,483,056 × 0.53 per 1000 population (52) + Canadian population 31,127,234 × 0.57 per 1000 population (53)) × Absolute difference

Conflict of interest statement: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tom P. Aufderheide, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Peter J. Kudenchuk, Seattle, Washington, USA

Jerris R. Hedges, Portland, Oregon, USA

Graham Nichol, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Richard E. Kerber, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Paul Dorian, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Daniel P. Davis, San Diego, California, USA

Ahamed H. Idris, Dallas, Texas, USA

Clifton W. Callaway, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Scott Emerson, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Ian G. Stiell, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Thomas E. Terndrup, Birmingham, Alabama, USA

References

- 1.Niemann JT. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1992 Oct 8;327(15):1075–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg MS, Horwood BT, Cummins RO, Reynolds-Haertle R, Hearne TR. Cardiac arrest and resuscitation: a tale of 29 cities. Ann Emerg Med. 1990 Feb;19(2):179–86. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker LB, Ostrander MP, Barrett J, Kondos GT. Outcomes of CPR in a Large Metropolitan Area- Where are the Survivors? Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(4):355–61. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81654-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichol G, Stiell IG, Laupacis A, Pham B, De Maio V, Wells GA. A Cumulative Metaanalysis Of The Effectiveness of Defibrillator-Capable Emergency Medical Services For Victims Of Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(4):517–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis DP, Garberson LA, Andrusiek DL, Hostler D, Daya M, Pirrallo R, Craig A, Stephens S, Larsen J, Drum AF, Fowler R. A Descriptive Analysis of Emergency Medical Service Systems Participating in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) Network. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007 Oct-Dec;11(4):369–82. doi: 10.1080/10903120701537147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lurie KG, Voelckel WG, Zielinski T, McKnite S, Lindstrom P, Peterson C, et al. Improving standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation with an inspiratory impedance threshold valve in a porcine model of cardiac arrest. Anesth Analg. 2001 Sep;93(3):649–55. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200109000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lurie KG, Barnes T, Zielinski T, McKnite D. Evaluation of a prototypic inspiratory impedance threshold valve designed to enhance the efficiency of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Respir Care. 2003;48(1):52–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lurie KG, Voelckel W, Plaisance P, et al. Use of an inspiratory impedance threshold valve during CPR: a progress report. Resuscitation. 2000;44(3):219–30. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langhelle A, Stromme T, Sunde K, et al. Inspiratory impedance threshold valve during CPR. Resuscitation. 2002;52(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lurie KG, Zielinski T, McKnite S, Aufderheide TP, Voelckel W, et al. Use of an inspiratory impedance valve improves neurologically intact survival in a porcine model of ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;105(1):124–9. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yannopoulos D, Aufderheide TP, McKnite S, Kotsifas K, Charris R, Nadkarni V, Lurie KG. Hemodynamic and respiratory effects of negative tracheal pressure during CPR in pigs. Resuscitation. 2006 Jun;69(3):487–94. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babbs CF, Yannopoulos D. A dose-response curve for the negative bias pressure of an intrathoracic pressure regulator during CPR. Resuscitation. 2006 Dec;71(3):365–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plaisance P, Lurie KG, Payen D. Inspiratory impedance during active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomized evaluation in patients in cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2000 Mar 7;101(9):989–94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lurie KG, Voelckel WG, Zielinski T, McKnite S, Lindstrom P, Peterson C, et al. Improving standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation with an inspiratory impedance threshold valve in a porcine model of cardiac arrest. Anesth Analg. 2001 Sep;93(3):649–55. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200109000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolcke BB, Mauer DK, Schoefmann MF, Teichmann H, Provo TA, Lindner KH, et al. Comparison of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus the combination of active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation and an inspiratory impedance threshold device for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003 Nov 4;108(18):2201–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095787.99180.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lurie KG, Mulligan KA, McKnite S, Detloff B, Lindstrom P, Lindner KH. Optimizing standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation with an inspiratory impedance threshold valve. Chest. 1998 Apr;113(4):1084–90. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.4.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aufderheide TP, Lurie KG. Vital organ blood flow with the impedance threshold device. Crit Care Med. 2006 Dec;34(12 Suppl):S466–S473. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000246013.47237.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yannopoulos D, Sigurdsson G, McKnite S, Benditt D, Lurie KG. Reducing ventilation frequency combined with an inspiratory impedance device improves CPR efficiency in swine model of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2004 Apr;61(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigurdsson G, Yannopoulos D, McKnite SH, Lurie KG. Cardiorespiratory interactions and blood flow generation during cardiac arrest and other states of low blood flow. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003 Jun;9(3):183–8. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aufderheide TP, Sigurdsson G, Pirrallo RG, Yannopoulos D, McKnite S, von Briesen C, et al. Hyperventilation-induced hypotension during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2004 Apr 27;109(16):1960–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126594.79136.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yannopoulos D, Aufderheide T. Acute management of sudden cardiac death in adults based upon new CPR guidelines. Europace. 2007 Jan;9(1):2–9. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yannopoulos D, Tang W, Roussos C, Aufderheide TP, Idris AH, Lurie KG. Reducing ventilation frequency during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a porcine model of cardiac arrest. Respir Care. 2005 May;50(5):601–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yannopoulos D, Aufderheide TP, Gabrielli A, Beiser DG, McKnite SH, Pirrallo RG, Wigginton J, Becker L, Vanden Hoek T, Tang W, Nadkarni VM, Klein JP, Idris AH, Lurie KG. Clinical and hemodynamic comparison of 15:2 and 30:2 compression-to-ventilation ratios for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 2006 May;34(5):1444–1449. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000216705.83305.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milander MM, Hiscok PS, Sanders AB, Kern KB, Berg RA, Ewy GA. Chest compression and ventilation rates during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: the effects of audible tone guidance. Acad Emerg Med. 1995 Aug;2(8):708–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abella BS, Alvarado JP, Myklebust H, Edelson DP, Barry A, O'Hearn N, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005 Jan 19;293(3):305–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wik L, Kramer-Johansen J, Myklebust H, Sorebo H, Svensson L, Fellows B, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005 Jan 19;293(3):299–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yannopoulos D, McKnite S, Aufderheide TP, Sigurdsson G, Pirrallo RG, Benditt D, Lurie KG. Effects of incomplete chest wall decompression during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on coronary and cerebral perfusion pressures in a porcine model of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2005 Mar;64(3):363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aufderheide TP, Pirrallo RG, Yannopoulos D, Klein JP, von Briesen C, Sparks CW, et al. Incomplete chest wall decompression: a clinical evaluation of CPR performance by EMS personnel and assessment of alternative manual chest compression-decompression techniques. Resuscitation. 2005 Mar;64(3):353–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aufderheide T, Pirrallo RG, Provo TA, Lurie KG. Clinical evaluation of an inspiratory impedance threshold device during standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2005 Apr;33(4):734–740. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000155909.09061.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirrallo RG, Aufderheide TP, Provo TA, Lurie KG. Effect of an inspiratory impedance threshold device on hemodynamics during conventional manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005 Jul;66(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thayne RC, Thomas DC, Neville JD, van Dellen A. Use of an impedance threshold device improves short-term outcomes following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. Oct;67(1):103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roccaforte WH, Burke WJ, Bayer BL, Wengel SP. Validation of a Telephone Version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1992;40:697–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State:” a Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002 Feb;40(2):113–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP, Conley DM, Potter JF. The reliability and validity of the Geriatric Depression Rating Scale administered by telephone. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995 Jun;43(6):674–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.