Abstract

In colonoscopic study, benign colorectal strictures with or without symptomatic pain are not rarely encountered. Benign colorectal stricture can be caused by a number of problems, such as anastomotic stricture after surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, postendoscopic submucosal dissection, diverticular disease, ischemic colitis, and so on. There are various modalities for the management of benign colorectal stricture. Endoscopic balloon dilatation is generally considered as the primary treatment for benign colorectal stricture. In refractory benign colorectal strictures, several treatment sessions of balloon dilatation are needed for successful dilatation. The self-expandable metal stent and many combined techniques are performed at present. However, there is no specific algorithmic modality for refractory benign colorectal strictures.

Keywords: Colorectal surgery; Dilatation; Endoscopy, gastrointestinal

INTRODUCTION

Benign colorectal strictures can develop after diverticulitis, ischemic colitis, radiation colitis, or colonic resection. Recently, colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection has become another possible culprit for the development of this benign stricture, which usually occurs after resection of a lateral spreading tumor, occupying 75% of the lumen. Surgical treatment of these lesions is technically challenging because of the fibrosis and/or inflammation. Anastomotic strictures after surgery, occurring in 5% to 20% of cases after low anterior resection, could be a serious condition that may require endoscopic or surgical treatment. Despite this serious condition, most strictures could be managed successfully with several treatment modalities, such as direct digital dilation, transanal surgical treatment, endoscopic balloon dilation, and stent insertion. However, other varieties of endoscopic or surgical techniques are required in refractory strictures, especially after failure of the first endoscopic management. Data on refractory cases in colorectal benign strictures are limited and this will be discussed.

ENDOSCOPIC MANAGEMENT OF BENIGN COLORECTAL STRICTURES

Balloon dilation

Endoscopic balloon dilation has been used as a first treatment modality for the treatment of benign colorectal strictures. However, varying results have been reported with regard to the success rate of this procedure.1,2 Despite its simplicity and immediate efficacy in up to 80% of cases, this technique requires several treatment sessions and is associated with a significant rate of recurrent benign stenosis. Predictors of a successful outcome include: a relatively narrow stenosis (<10 mm), a short segment stricture (<4 cm), and anastomotic strictures. Poor predictors include: numerous strictures, complete obstruction, associated fistulas within the stricture, active inflammation around the stricture, recent surgery, a tight angulation, and malignancy.3

Balloons usually exert a radial vector force against the strictured tissue, and these often require sequential dilation using a larger balloon over two to three endoscopic sessions in order to achieve long-term success. However, this may not be determined until the results of the first dilation are known. Immediate relief of symptoms has been reported in 77% of patients and long-term relief in 44% of patients.4

Fifty-five patients with Crohn symptomatic strictures were studied. Endoscopic treatment was successful in 76% and surgery was required in 2%. The long-term success of endoscopic balloon dilation was reported to depend on the type of strictures, their location, and their length. Failure of endoscopic treatment was observed in long-segment strictures in the terminal ileum.5 In one study, 55 patients with ileocolonic strictures secondary to Crohn disease underwent 78 balloon dilations. Dilatation resulted in complete relief of obstructive symptoms in 34 patients after one or repetitive dilatations. Total long-term success rate was 62%. Complications of peritoneal perforation occurred in six patients. However, four of these patients showed improvement with administration of intravenous fluid and antibiotics.6

Balloon dilatation is more useful in patients with anastomotic strictures. In one study, endoscopic dilatation in 94 patients with postoperative anastomotic stenosis was successful in 59% of patients who underwent resection for cancer and in 88% who underwent resection for a benign condition. Complications occurred in 17 patients (benign restenosis, perforation, abscess). High success and low risk rates make endoscopic balloon dilatation the treatment of choice to avoid high risk of reoperation in patient with benign anstomoticstrictures.2

Self-expandable metal stent

Placement of a self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) has been suggested as one of therapeutic modalities for the relief of benign colorectal strictures.7 Unlike uncovered stents, fully covered SEMS has several advantages in the management of benign strictures. These fully covered SEMS have limited local tissue reaction; thus, they are used in benign conditions such as colonic strictures, fistulas, perforation, and leaks in the digestive tract.8,9

Permanent insertion of SEMS is also associated with a significant and unacceptable rate of complications, such as new stricture formation and perforation. Only a few studies have reported on the usefulness of fully covered SEMS in patients with benign colorectal strictures. One recent study, which included 43 patients with symptomatic strictures, reported on the effectiveness of fully covered SEMS in the management of benign colorectal strictures. All patients with strictures during a 6-year study period were included. The efficacy of the stent, technical success, stent retrieval, safety, and recurrence of symptoms were evaluated during the follow-up. SEMS insertion was successful in all patients. Clinical success was obtained in 81% and migration was observed in 63%. The mean duration of stents was 21 days. Recurrence of obstructive symptoms was observed in 53%, irrespective of migration. The authors insisted that fully covered SEMS is safe and effective for treatment of symptomatic benign strictures, despite a high rate of spontaneous migration.10 Although this study could not define the predictive risk factors for clinical success or recurrence, refractory patients who underwent several balloon dilation sessions were successfully managed. Conduct of future studies will be needed in order to define the best treatment option, such as balloon dilation vs. early fully covered SEMS insertion.

Biodegradable stents have recently been developed for use in the management of refractory benign esophageal strictures. The poly-L-lactic based stent and polydiosanone based stent were mainly used for refractory benign esophageal strictures. In particular, a polydiosanone stent is a semicrystalline, biodegradable polymer, which degrades by random hydrolysis and at low pH. None of the degradation products is harmful. The prolonged dilatory effect before stent absorption and the progressive stent degradation could represent a favorable solution for patients with benign strictures refractory to standard dilation therapy compared with self-expandable metal and plastic stents for esophageal strictures.11,12 Currently, use of biodegradable stents in the management of colorectal refractory benign strictures, same as benign esophageal strictures, has been attempted. Treatment of 10 patients with postsurgical colorectal strictures (n=7) and fistula (n=3) with biodegradable polydiosanone stents was an effective alternative in short to medium terms. The fistulas were successfully closed in all patients. Among the six patients who received stents for strictures, symptoms resolved in five; in the remaining patients, the stent migrated shortly after the endoscopy. If biodegradable stents are to be used for the treatment of strictures and fistulas, the proximity of the stricture should be close to the anus because of the inflexibility, and the need to fix stents in the colon was important.13 In another study, 11 patients with postsurgical benign strictures located within 20 cm from the anal verge, refractory to mechanical or pneumatic dilation (at least three sessions) were included. Five of them had complete resolution of the stricture and relief of symptoms. Two of 11 patients required surgical treatment during the follow-up period. The overall success rate of the biodegradable stent was 45%.14 Treatment using biodegradable stents in the management of refractory anastomotic colorectal stricture is very safe. They concluded that, instead of a nondedicated biodegradable stent which carried a high migration risk, dedicated stents with a large diameter and antimigration findings could improve the outcome of patients with refractory benign colorectal stricture.

COMBINED TECHNIQUES

Most benign colorectal strictures could be managed with several sessions of balloon dilation or fully covered SEMS insertion. Several studies have reported on the use of combined endoscopic or a novel method other than these techniques. There are many modalities for refractory benign colorectal strictures. Most modalities originated from the method for refractory benign esophageal stricture. Variable therapeutic options continue to evolve and have taken much of their lead from the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures.

A combined technique of endoscopic electroincision using the tip of a polypectomy snare or papillotome and balloon dilatation was used in 36 patients with benign colorectal anastomotic strictures. Recurrence of the stricture was found in only five of these patients at 1-year follow-up, and all were treated successfully by further balloon dilatation.15 The other combined modality was used at the completely obstructed anastomosis stricture. A puncture catheter (polyethylene catheter) with a needle and a flexible metallic sheath at the distal end could penetrate the central obstructed anastomosis stricture under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control. The guide-wire was passed through the catheter and pneumatic dilatation was then performed. More expandable dilatation was performed repeatedly for successful web destruction.16 Another study also reported that endoscopic reanastomosis in a sigmoid cancer patient with a completely strictured colorectal anastomosis was performed successfully using a transrectal puncture needle and wire guided balloon dilatation.17 A novel hybrid technique using transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) and balloon dilation for the treatment of a benign complete colorectal anastomotic stricture has been reported.18 The stricture was incised with a vessel-sealing device using a 20-cm TEM rectoscope. Endoscopic balloon dilation was performed after reopening of the lumen. TEM-assisted balloon strictureplasty could be a minimally invasive solution for bridging the gap between radical surgery and conservative treatment. In refractory benign strictures involved around the rectum, electrocautery can be performed via flexible sigmoidoscopy using a urologic resectoscope19 or by TEM with balloon dilatation. Laser ablation has also been reported for the treatment of strictures.20 One study reported the use of TEM combined with a Nd:YAG laser for resection of an anastomotic stricture.21 Dilation of the stricture using TEM can be achieved at the same time as resection.

CONCLUSIONS

Novel endoscopic techniques are emerging for the management of refractory benign colorectal strictures; these would be of great help in the management of patients who suffered from strictures.

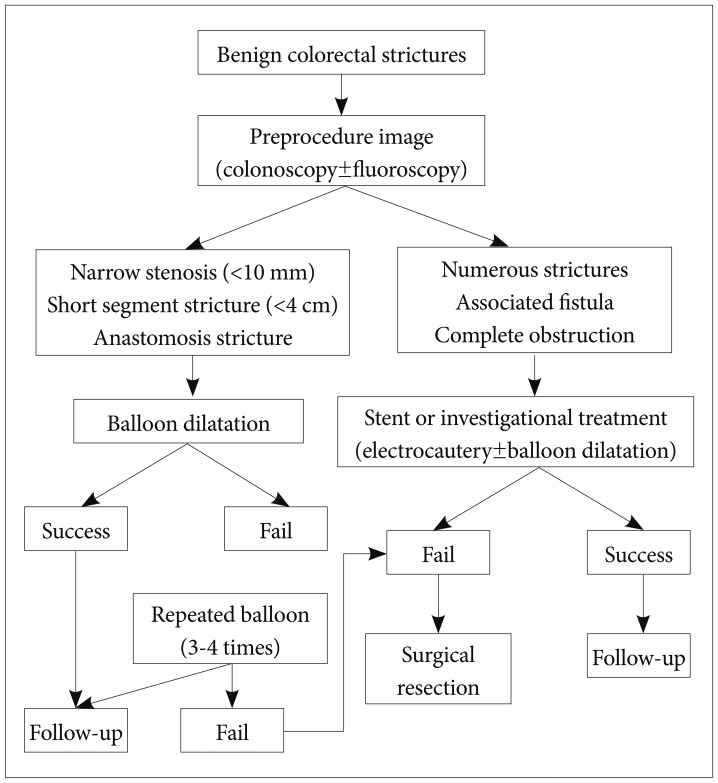

Endoscopic balloon dilatation is considered as the first line treatment modality. Endoscopic dilation of colonic strictures offers many advantages over surgical management, including preservation of intestinal length. The procedure for balloon dilatation is quick, simple, and can be easily controlled by endoscopists. Repeat dilations are often necessary, and the number of repeated dilations seems to vary between two and three or more. If a trial of several balloon dilatations fails, the patient will need an alternative modality. The secondary use of a SEMS is also considered. It is safe and effective for the treatment of refractory benign colonic strictures, despite a high rate of spontaneous migration. In particular, the biodegradable stent is very safe and does not need to be retrieved because it will be degraded naturally with tissue reaction. However, stent insertion was not indicated in numerous strictures. Combined investigational modality can also be considered if only one modality like balloon or SEMS cannot be performed due to a poor situation (e.g., numerous strictures). Wire guided balloon dilation after use of a puncture needle, eletroincision, and TEM using balloon dilatation and combined techniques could be attempted. These different treatments suggest that a single method is not adequate for all refractory benign colorectal strictures. What is important is that the etiology and pathogenesis behind colorectal stricture should be analyzed, given the success rate of a nonoperative intervention method. Finally, surgical treatment is reserved for patients who fail all endoscopic remediation or those are not candidates for endoscopic treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical Management of benign colorectal strictures. Endoscopic balloon dilatation is generally considered as the primary treatment for benign colorectal stricture. In refractory cases, several treatment sessions of balloon dilatation are usually needed. Self-expandable metal stent and many other combined techniques are under evaluation for refractory benign conditions.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Garcea G, Sutton CD, Lloyd TD, Jameson J, Scott A, Kelly MJ. Management of benign rectal strictures: a review of present therapeutic procedures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1451–1460. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6792-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suchan KL, Muldner A, Manegold BC. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative colorectal anastomotic strictures. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1110–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8926-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemberg B, Vargo JJ. Balloon dilation of colonic strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2123–2125. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breysem Y, Janssens JF, Coremans G, Vantrappen G, Hendrickx G, Rutgeerts P. Endoscopic balloon dilation of colonic and ileo-colonic Crohn's strictures: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:142–147. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonin EA, Baron TH. Update on the indications and use of colonic stents. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:374–382. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller T, Rieder B, Bechtner G, Pfeiffer A. The response of Crohn's strictures to endoscopic balloon dilation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:634–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liangpunsakul S, Rex DK. Management of benign colonic strictures. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;5:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsereteli Z, Sporn E, Geiger TM, et al. Placement of a covered polyester stent prevents complications from a colorectal anastomotic leak and supports healing: randomized controlled trial in a large animal model. Surgery. 2008;144:786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forshaw MJ, Sankararajah D, Stewart M, Parker MC. Self-expanding metallic stents in the treatment of benign colorectal disease: indications and outcomes. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanbiervliet G, Bichard P, Demarquay JF, et al. Fully covered self-expanding metal stents for benign colonic strictures. Endoscopy. 2013;45:35–41. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito Y, Tanaka T, Andoh A, et al. Novel biodegradable stents for benign esophageal strictures following endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:330–333. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9873-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito Y, Tanaka T, Andoh A, et al. Usefulness of biodegradable stents constructed of poly-l-lactic acid monofilaments in patients with benign esophageal stenosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3977–3980. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez Roldán F, González Carro P, Villafáñez García MC, et al. Usefulness of biodegradable polydioxanone stents in the treatment of postsurgical colorectal strictures and fistulas. Endoscopy. 2012;44:297–300. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Repici A, Pagano N, Rando G, et al. A retrospective analysis of early and late outcome of biodegradable stent placement in the management of refractory anastomotic colorectal strictures. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2487–2491. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truong S, Willis S, Schumpelick V. Endoscopic therapy of benign anastomotic strictures of the colorectum by electroincision and balloon dilatation. Endoscopy. 1997;29:845–849. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curcio G, Spada M, di Francesco F, et al. Completely obstructed colorectal anastomosis: a new non-electrosurgical endoscopic approach before balloon dilatation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4751–4754. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i37.4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dafnis G. A novel technique for endoscopic reanastomosis in a patient with a completely strictured colorectal anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2008;40(Suppl 2):E79–E80. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolthuis AM, Rutgeerts P, Penninckx F, D'Hoore A. A novel hybrid technique using transanal endoscopic microsurgery and balloon dilation in the treatment of a benign complete colorectal anastomotic stricture. Endoscopy. 2011;43(Suppl 2 UCTN):E176–E177. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton CD, Marshall LJ, White SA, Flint N, Berry DP, Kelly MJ. Tenyear experience of endoscopic transanal resection. Ann Surg. 2002;235:355–362. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luck A, Chapuis P, Sinclair G, Hood J. Endoscopic laser stricturotomy and balloon dilatation for benign colorectal strictures. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:594–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2001.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato K, Saito T, Matsuda M, Imai M, Kasai S, Mito M. Successful treatment of a rectal anastomotic stenosis by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) using the contact Nd:YAG laser. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:485–487. doi: 10.1007/s004649900398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]