Abstract

Background: Healthy dietary patterns may protect against age-related cognitive decline, but results of studies have been inconsistent.

Objective: We examined associations between Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)– and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change in a prospective, population-based study.

Design: Participants included 3831 men and women ≥65 y of age who were residents of Cache County, UT, in 1995. Cognitive function was assessed by using the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) ≤4 times over 11 y. Diet-adherence scores were computed by summing across the energy-adjusted rank-order of individual food and nutrient components and categorizing participants into quintiles of the distribution of the diet accordance score. Mixed-effects repeated-measures models were used to examine 3MS scores over time across increasing quintiles of dietary accordance scores and individual food components that comprised each score.

Results: The range of rank-order DASH and Mediterranean diet scores was 1661–25,596 and 2407–26,947, respectively. Higher DASH and Mediterranean diet scores were associated with higher average 3MS scores. People in quintile 5 of DASH averaged 0.97 points higher than those in quintile 1 (P = 0.001). The corresponding difference for Mediterranean quintiles was 0.94 (P = 0.001). These differences were consistent over 11 y. Higher intakes of whole grains and nuts and legumes were also associated with higher average 3MS scores [mean quintile 5 compared with 1 differences: 1.19 (P < 0.001), 1.22 (P < 0.001), respectively].

Conclusions: Higher levels of accordance with both the DASH and Mediterranean dietary patterns were associated with consistently higher levels of cognitive function in elderly men and women over an 11-y period. Whole grains and nuts and legumes were positively associated with higher cognitive functions and may be core neuroprotective foods common to various healthy plant-centered diets around the globe.

INTRODUCTION

Age-related cognitive decline is a result of neurodegenerative diseases, the most common of which is Alzheimer disease (AD)4, which is the third most costly disease in the United States (1). A delay of the onset of AD by 5 y has been projected to reduce its prevalence by 50%, and thus, lifestyle changes with modest effects could translate into a large reduction in disease burden (2).

Previous studies of single nutrients and risk of age-related cognitive decline and AD have provided mixed results (3). Single-nutrient analyses have largely ignored the complexity of the diet, and defining dietary exposures as a dietary pattern may better predict disease risk and provide a clearer link to food-based public health recommendations (4).

Two dietary patterns of interest are the Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. A traditional Mediterranean dietary pattern, which was shown by Keys (5) to be associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease in the Seven Countries Study and popularized in the mid-1970s in his book (6), includes largely whole, minimally processed plant foods including cereal grains, legumes, vegetables, fruit, nuts, and fish with small amounts of meat, milk, and dairy products and a regular, modest intake of alcohol (7, 8). The importance of the Mediterranean-type dietary patterns in maintaining cognitive function is uncertain because, in some studies, it has shown a protective effect (9–14), whereas in other studies, it has not shown a protective effect (15–19). Diets in the Mediterranean region are diverse as are the definitions of Mediterranean diets used in scientific studies (7), and the concept of a Mediterranean diet as a unified, meaningful regional and global dietary pattern has been questioned (20, 21).

The DASH diet substantially reduced elevated blood pressure in clinical trials (22) and is recommended in the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans (23). The DASH combination diet emphasizes fruit, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and includes whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts and is reduced in fats, red meat, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages. Because of the known association between hypertension and cognitive function, it is plausible that the DASH diet may also reduce risk of cognitive decline (24).

In the current study, we evaluated prospective associations between DASH and Mediterranean dietary accordance scores and individual food groups that contribute to each dietary score and cognitive function in elderly men and women in the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging [hereafter referred to as the Cache County Memory Study (CCMS)].

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

The CCMS is a large population-based prospective study of the prevalence and incidence of dementia in elderly residents of Cache County, UT. In 1995, all residents of Cache County ≥65 y of age were invited to participate, and 5092 (90%) subjects completed the baseline interview (1995–1996) (25). Reassessments of the cohort were completed in 1998–1999, 2002–2003, and 2005–2006. The average length of follow-up for subjects who completed all 4 assessments was 10.6 y. The cohort is predominately non-Hispanic White (>90%) and the genetic make-up is broadly representative of other US populations of Northern European ancestry (26). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Utah State University, the Johns Hopkins University, and Duke University. All study participants, or their next of kin in cases of impaired persons, gave written informed consent to participate.

Of the 5092 participants who completed the baseline interview, 355 subjects were shown to be demented at baseline [Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) <87] and were not asked to complete the self-administered food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (27). Of the 4737 subjects who were asked to complete the FFQ, 3829 subjects (81%) completed and returned the questionnaire. An additional 249 participants were excluded because they provided implausible energy intakes (≤500 or ≥5000 kcal/d; n = 125) or because they were later diagnosed as having prevalent dementia (n = 124), which left 3580 subjects for analysis.

Assessments

The baseline survey included information on demographic characteristics, health history, family history of dementia, use of medications and dietary supplements, alcohol, tobacco, and other lifestyle factors. The 3MS for epidemiologic studies (25) was used to assess cognitive function at baseline and subsequent assessments. The 3MS is a 100-point expanded version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (28) that has been used in many epidemiologic studies and shown to be useful as a global measure of cognitive function and decline in noninstitutionalized elderly men and women (29). A multistage clinical assessment protocol, which has been described in detail elsewhere, was used to diagnose dementia (30). Participants diagnosed with dementia did not complete a 3MS at subsequent assessments (ie, we had a 3MS score at baseline and each subsequent visit up to and including the wave when the individual was diagnosed with dementia).

The usual dietary intake over the previous year was also assessed at baseline (1995) by using a 142-item self-administered FFQ patterned after the methods developed for use in the Nurses’ Health Study (Harvard FFQ) with a food list modified to include foods frequently included in 24-h recalls collected from elderly people who were residing in a neighboring county (16). Similar questionnaires have been shown to provide reasonable estimates of the usual dietary intake in populations of varied ages and demographic characteristics including a population of elderly women (31, 32). Participants reported their frequency of consumption of listed food items or groups. The nutrient composition of food items was obtained by using a time-specific version of the Food Processor Program (version 7.0; ESHA Research) nutrient-composition database. Average daily intakes of nutrients were computed by multiplying the nutrient content of the food item by the reported frequency of intake and summing over all food items. Daily intakes of nutrients and servings of food groups used to create diet accordance scores were adjusted for the total energy intake by using the residual regression method of Willett et al (31).

DASH and Mediterranean diet accordance scores were computed from food and nutrient components emphasized or minimized in the dietary patterns. The DASH diet score included the following 8 components: high intakes of fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, nuts and legumes, and whole grains and low intakes of sodium, sweetened beverages, and red and processed meats. These components were selected to represent food groups targeted in the DASH diet (33) and were similar to the components defined by others who have examined accordance to a DASH-style eating pattern in population-based studies (34–36); most of the studies focused on food or food-group targets, but at least one study was nutrient based (34). We chose a scoring paradigm most similar to that reported by Fung et al (35). The Mediterranean diet accordance score also included the following 8 components: high intakes of fruit, vegetables, total grains, fish, legumes, and ratio of MUFAs to SFAs and low intakes of meat and meat products and high-fat dairy products. These components were selected to represent food groups defined by other authors who have examined accordance to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern, although there has been considerable variability in the components used to define a Mediterranean-style diet in the literature (7, 37).

Moderate alcohol consumption is often included in Mediterranean diet accordance scores but was not included here because of the low rates of alcohol consumption in this population. Only 2.7% of the study population reported consuming ≥1 alcoholic beverage/d. High intakes of fruit, vegetables, whole grains and nuts and legumes are common components of both the DASH score and Mediterranean score. Individual food items obtained from the FFQ used to define DASH and Mediterranean dietary patterns in the current study are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Food and nutrient groups and scoring criteria for DASH and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns in the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging (n = 3580)1

| Food group | Food items | Scoring criteria2 | Median (25th, 75th percentiles) | DASH diet score components | Mediterranean diet score components |

| All grains (servings/d) | Dark and white bread or pita, cold breakfast cereal, cooked cereal, oatmeal, popcorn, other grains (bulgur, kasha, couscous), rice crackers, pasta, tortillas (n = 14) | Positive | 2.9 (2.0, 4.1) | No | Yes |

| Whole grains (servings/d) | Dark bread or pita, whole-grain cold breakfast cereal, cooked cereal, oatmeal, popcorn, other grains (bulgur, kasha, couscous) (n = 6) | Positive | 1.14 (0.57, 2.2) | Yes | No |

| Legumes (servings/d) | Dried beans, peas, lentils, tofu, soybeans, green beans (n = 6) | Positive | 0.21 (0.14, 0.57) | Yes3 | Yes |

| Nuts (servings/d) | Peanuts, peanut butter, other nuts (n = 3) | Positive | 0.14 (0.13, 0.43) | Yes3 | No |

| Fruit (servings/d) | All fruit and 100% juices (n = 15) | Positive | 2.4 (1.5, 3.4) | Yes | Yes |

| Vegetables (servings/d) | All vegetables except potatoes and legumes (n = 23) | Positive | 2.3 (1.5, 3.6) | Yes | Yes |

| All meat (servings/d) | Beef, pork, lamb, chicken, turkey, liver, salami, bologna, hot dogs, bacon, sausage, processed meat (n = 12) | Negative | 0.99 (0.63, 1.6) | No | Yes |

| Red and processed meat (servings/d) | Beef, pork, lamb, liver, salami, bologna, hot dogs, bacon, sausage, other processed meat (n = 10) | Negative | 0.84 (0.35, 1.14) | Yes | No |

| Fish (servings/d) | Canned tuna fish, salmon/dark meat fish, other white meat fish, fish sandwiches (n = 4) | Positive | 0.14 (0.07, 0.28) | No | Yes |

| Full-fat dairy (servings/d) | Whole milk, chocolate milk, ice cream, cheddar and other hard cheese (n = 4) | Negative | 0.5 (0.21, 0.93) | No | Yes |

| Low-fat dairy (servings/d) | Skim or low-fat milk, yogurt, cottage or ricotta cheese (n = 4) | Positive | 1.07 (0.43, 2.5) | Yes | No |

| Sweetened beverages (servings/d) | Soda pop, punch, and other sweetened beverages (n = 6) | Negative | 0.28 (0.07, 0.86) | Yes | No |

| MUFA:SUFA ratio | Ratio of total monounsaturated fatty acids/total saturated fatty acids | Positive | 1.07 (0.96, 1.17) | No | Yes |

| Sodium (mg) | Sum of sodium content of all foods | Negative | 2616 (1833, 3233) | Yes | No |

Food and nutrient intakes were adjusted for total energy intake by using the residual regression method. DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

Positive scoring denotes that a participant who consumed the lowest amount received a rank score of 1, and a participant who consumed the highest amount received a rank score of 3850; inverse scoring denotes that a participant who consumed the lowest amount received a rank score of 3580, and a participant who consumed the highest amount received a rank score of 1.

Nuts and legumes were combined for the DASH-style diet pattern score.

DASH and Mediterranean diet accordance scores were computed by summing across ranked scores of each relevant food and nutrient component. Participants were ranked according to their intake of each food component of both the DASH and Mediterranean-style eating patterns including fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy foods, whole grains, total grains, nuts and legumes, the MUFA:SUFA ratio, and fish (the participant who consumed the highest amount in each food group received a rank of 3580, and the participant who consumed the lowest amount received a rank of 1). Participants were ranked in reverse order of their intakes of the red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, sodium, and full-fat dairy foods. To create DASH and Mediterranean accordance scores, the respective food and nutrient component rank scores were summed, and participants were categorized into quintiles of the cohort's distribution of the DASH and Mediterranean diet accordance score. Other authors have created similar accordance scores by summing across quintile scores for food groups (19) or on the basis of dichotomous scores above or below the median (37), but summing across ranks preserves more information from the original food groups while putting each food group on an equal scale and reducing the impact of skewness and outliers in distributions of the original scores.

Statistical analysis

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences between continuous variables over quintiles of diet scores (Tables 2 and 3) because several of the variables had highly skewed distributions. The power of the Kruskal-Wallis test remained high because of the large sample size. The chi-square test was used to evaluate differences for categorical variables (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Participant characteristics by quintiles of the 8-component DASH diet score in the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging1

| Quintile 1 (n = 716) | Quintile 2 (n = 716) | Quintile 3 (n = 716) | Quintile 4 (n = 714) | Quintile 5 (n = 718) | ||

| 1661–11,236 | 11,248–13,362 | 13,371–15,329 | 15,330–17,416 | 17,418–26,596 | P | |

| Mediterranean score | 11,164.5; 4204.82 | 13,079.5; 3454.5 | 14,282.5; 4030.2 | 15,458.0; 4193.2 | 17,683.0; 4336.0 | <0.001 |

| Baseline 3MS: 1995–1996 | 92.0; 7.0 | 92.0; 6.4 | 93.0; 5.8 | 93.0; 6.1 | 94.0; 6.1 | <0.001 |

| Age (y) | 73.8; 9.6 | 73.5; 9.9 | 74.3; 9.9 | 74.0; 10.4 | 74.8; 9.8 | 0.475 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8; 5.5 | 25.9; 5.9 | 26.4; 5.7 | 25.7; 5.7 | 25.0; 5.2 | <0.001 |

| M (%) | 54.9 | 44.6 | 40.4 | 36.6 | 38 | <0.001 |

| More than high school education (%) | 39.9 | 45.8 | 46.8 | 53.5 | 60.9 | <0.001 |

| Daily moderate exercise (%) | 32.8 | 35.6 | 38.8 | 39.9 | 45.7 | <0.001 |

| MVM use (yes) (%) | 33.1 | 39.9 | 43.4 | 46.5 | 50.1 | <0.001 |

| Ever smoke (%)3 | 28.5 | 19.7 | 19.1 | 16.1 | 11.0 | <0.001 |

| Ever drank (%)3 | 23.1 | 14.3 | 15.7 | 14.8 | 13.0 | <0.001 |

| At least one APOE e4 allele (%) | 32.0 | 32.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 32.0 | 0.586 |

| Dietary intake (/d) | ||||||

| Energy (kcal) | 2031.1; 1038.8 | 1680.8; 957.9 | 1736.3; 991.2 | 1734.5; 886.2 | 1952.8; 823.5 | <0.001 |

| Fat (percentage of energy) | 35.6; 5.2 | 32.6; 5.4 | 31.0; 5.5 | 29.0; 5.5 | 26.8; 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrate (percentage of energy) | 48.6; 6.9 | 51.9; 6.7 | 53.4; 6.7 | 56.2; 6.8 | 58.6; 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Protein (percentage of energy) | 17.3; 3.2 | 17.4; 3.7 | 17.9; 3.6 | 17.6; 3.4 | 17.6; 3.3 | 0.039 |

| Saturated fat (g)4 | 29.2; 6.3 | 25.1; 5.0 | 23.2; 5.1 | 21.6; 5.2 | 17.9; 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Ratio of MUFAs to SFAs | 1.1; 0.2 | 1.1; 0.2 | 1.1; 0.2 | 1.1; 0.2 | 1.1; 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g)4 | 1.2; 0.4 | 1.2; 0.3 | 1.1; 0.3 | 1.1; 0.3 | 1.1; 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Omega-6 fatty acids (g)4 | 11.3; 3.6 | 10.9; 2.8 | 10.4; 2.9 | 10.0; 3.0 | 9.4; 3.3 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg)4 | 320.7; 164.9 | 285.8; 134.5 | 269.4; 125.4 | 246.9; 113.5 | 218.0; 131.2 | <0.001 |

| Fiber (g)4 | 13.9; 5.1 | 16.7; 4.9 | 18.4; 5.1 | 20.3; 6.0 | 24.2; 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin C (mg)4 | 89.5; 56.9 | 113.1; 64.2 | 132.3; 65.6 | 147.7; 79.7 | 175.3; 87.2 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin E (mg)4 | 7.2; 1.9 | 7.5; 1.8 | 7.5; 1.7 | 7.7; 1.9 | 8.0; 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Folate (μg)4 | 243.1; 103.7 | 277.2; 93.0 | 300.0; 93.1 | 322.9; 122.5 | 358.5; 128.4 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B-6 (mg)4 | 1.9; 0.6 | 2.0; 0.6 | 2.1; 0.6 | 2.2; 0.7 | 2.4; 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B-12 (μg)4 | 5.3; 3.1 | 5.3; 2.5 | 5.4; 2.7 | 5.4; 2.5 | 5.1; 2.8 | 0.005 |

| Sodium (mg)4 | 2782.7; 632.7 | 2657.2; 558.4 | 2585.6; 488.8 | 2573.7; 534.7 | 2443.4; 520.1 | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg)4 | 712.1; 354.2 | 793.9; 356.4 | 870.8; 438.5 | 1009.1; 498.9 | 1155.4; 485.3 | <0.001 |

| Potassium (mg)4 | 2676.2; 666.4 | 3006.3; 605.1 | 3227.5; 674.1 | 3503.7; 707.2 | 3884.1; 828.0 | <0.001 |

| Magnesium (mg)4 | 253.8; 53.5 | 283.6; 43.8 | 305.4; 49.8 | 327.5; 55.9 | 361.8; 65.2 | <0.001 |

| Zinc (mg)4 | 10.9; 3.1 | 10.9; 2.7 | 11.1; 2.8 | 11.1; 3.1 | 11.0; 2.8 | 0.111 |

P values were obtained by using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; MVM, multivitamin-mineral supplement; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

Median; interquartile range (all such values).

An ever smoker was defined as a subject who reported ever regularly smoking; an ever drinker was defined as a subject who reported ever regularly drinking alcohol.

Energy-adjusted nutrient intakes per day.

TABLE 3.

Participant characteristics by quintiles of the 8-component Mediterranean diet score in the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging1

| Quintile 1 (n = 716) | Quintile 2 (n = 716) | Quintile 3 (n = 716) | Quintile 4 (n = 716) | Quintile 5 (n = 716) | ||

| 2407–11,224 | 11,229–13,315 | 13,318–15,240 | 15,242–17,451 | 17,456–26,947 | P | |

| DASH score | 11,146.5; 4535.02 | 12,921.5; 3814.2 | 14,099.0; 4039.2 | 15,483.0; 3959.8 | 17,653.5; 4096.8 | <0.001 |

| Baseline 3MS: 1995–1996 | 92.0; 8.0 | 93.0; 8.0 | 92.0; 8.0 | 93.0; 7.0 | 93.0; 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Age (y) | 73.8; 10.2 | 74.1; 10.2 | 74.4; 10.0 | 74.0; 9.7 | 74.2; 9.7 | 0.895 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7; 5.7 | 25.8; 5.8 | 25.8; 5.7 | 25.8; 5.4 | 25.4; 5.5 | 0.060 |

| M (%) | 54.4 | 47.6 | 40.6 | 37.0 | 34.8 | <0.001 |

| More than a high school education (%) | 43.1 | 47.8 | 48.1 | 48.7 | 59.2 | <0.001 |

| Daily moderate exercise (%) | 31.2 | 37.4 | 39.5 | 39.1 | 45.7 | <0.001 |

| MVM use (yes) (%) | 36.6 | 39.0 | 41.5 | 45.6 | 50.3 | <0.001 |

| Ever smoke (%)3 | 25.6 | 21.0 | 18.3 | 15.9 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Ever drank (%)3 | 21.4 | 17.3 | 14.8 | 13.6 | 13.3 | <0.001 |

| At least one copy of the APOE e4 allele (%) | 32.0 | 27.8 | 35.2 | 30.4 | 30.8 | 0.854 |

| Dietary intake (/d) | ||||||

| Energy (kcal) | 2043.2; 1063.3 | 1775.7; 973.5 | 1771.3; 981.1 | 1694.0; 841.3 | 1912.3; 859.0 | <0.001 |

| Fat (percentage of total energy) | 35.4; 5.7 | 32.5; 5.6 | 3.7; 5.5 | 29.6; 5.4 | 26.7; 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrate (percentage of total energy) | 48.9; 6.8 | 51.9; 7.1 | 53.7; 6.9 | 55.3; 6.5 | 58.8; 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Protein (percentage of total energy) | 17.4; 3.5 | 17.6; 3.7 | 17.8; 3.6 | 17.5; 3.2 | 17.4; 3.3 | 0.114 |

| Saturated fat (g)4 | 28.2; 7.5 | 25.1; 4.7 | 23.5; 4.8 | 21.9; 4.3 | 18.5; 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g)4 | 1.1; 0.4 | 1.1; 0.3 | 1.1; 0.3 | 1.2; 0.3 | 1.2; 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Omega-6 fatty acids (g)4 | 10.5; 3.6 | 10.6; 3.1 | 10.5; 3.0 | 10.8; 3.2 | 9.9; 3.4 | <0.001 |

| Ratio of MUFAs to SFAs | 1.0; 0.2 | 1.0; 0.2 | 1.1; 0.2 | 1.1; 0.2 | 1.2; 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg)4 | 307.0; 165.3 | 282.4; 136.6 | 273.0; 133.0 | 254.8; 124.5 | 225.1; 126.6 | <0.001 |

| Fiber (g)4 | 13.8; 5.5 | 16.6; 4.7 | 18.4; 5.8 | 20.0; 5.8 | 24.1; 8.6 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin C (mg)4 | 87.6; 58.4 | 113.9; 63.4 | 132.6; 70.9 | 143.6; 73.8 | 179.2; 89.3 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin E (mg)4 | 6.8; 1.9 | 7.3; 1.7 | 7.5; 1.6 | 7.9; 1.5 | 8.3; 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Folate (μg)4 | 246.0; 105.9 | 279.0; 97.3 | 297.2; 95.8 | 317.6; 100.8 | 365.2; 134.3 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B-6 (mg)4 | 1.8; 0.7 | 2.0; 0.6 | 2.1; 0.7 | 2.2; 0.7 | 2.4; 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B-12 (μg)4 | 5.5; 2.9 | 5.5; 2.7 | 5.4; 2.6 | 5.3; 2.5 | 4.9; 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Sodium (mg)4 | 2555.4; 712.9 | 2574.1; 583.8 | 2611.9; 506.5 | 2625.6; 500.0 | 2623.5; 577.3 | 0.011 |

| Calcium (mg)4 | 926.3; 557.1 | 849.3; 528.7 | 863.9; 480.4 | 875.4; 509.8 | 896.9; 491.7 | 0.057 |

| Potassium (mg)4 | 2809.8; 816.7 | 3081.4; 787.5 | 3222.3; 791.9 | 3334.5; 766.1 | 3723.3; 982.9 | <0.001 |

| Magnesium (mg)4 | 272.6; 68.5 | 289.8; 58.9 | 302.7; 63.7 | 315.3; 64.0 | 349.4; 77.4 | <0.001 |

| Zinc (mg)4 | 11.2; 3.4 | 11.1; 2.8 | 11.0; 2.7 | 10.9; 2.6 | 10.7; 3.0 | 0.033 |

P values were obtained by using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; MVM, multivitamin-mineral supplement; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

Median; interquartile range (all such values).

An ever smoker was defined as a subject who reported ever regularly smoking; an ever drinker was defined as a subject who reported ever regularly drinking alcohol.

Energy-adjusted nutrient intakes per day.

Repeated-measures mixed effects linear regression models were created with the SAS statistical software package (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc.) and used to examine associations between quintiles of the diet accordance scores and individual food components and the average 3MS score over 11 y of follow-up. The ordered variable that represented quintiles of the distribution of diet accordance scores were treated as both continuous and categorical variables in separate models with the lowest quintile of intake as the reference group. Including quintiles as continuous variables in the model (1 df) provided a test of the linear association of an increasing quintile of intake and 3MS scores (P-linear trend).

Multivariable models controlled for sex, age, age squared, level of education (no post–high school education compared with some post–high school education), an indicator for low BMI [(in kg/m2) <18.5], frequency of participation in moderate physical activity, regular multivitamin and minerals use (yes compared with no), and history of smoking (ever compared with never) and drinking alcohol (ever compared with never), and comorbidities including diabetes, myocardial infarction, and stroke (yes compared with no) because these variables were associated with both dietary patterns and 3MS scores. Both linear and quadratic terms for the follow-up time were included in mixed models to account for curvilinear trajectories of 3MS performance over time. Both linear and quadratic terms for age were included in mixed models to account for the curvilinear effect of age and 3MS scores. Interactions between the diet accordance scores and time (linear and quadratic effects) were tested by comparing the likelihood ratio test statistics between models with and without interaction terms. Reported P values were 2-sided, and the type I error rate for statistical significance was 0.05. A Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the P values of tests of individual food components of diet scores (Table 4). In addition, residuals from the models were skewed, but sample sizes were large, and when we transformed to normality by using −log(–3MS), our results were qualitatively unchanged, and thus, we present results for the more interpretable nontransformed 3MS.

TABLE 4.

Differences in 3MS scores by quintile (quintiles 2–5) scores of the DASH diet score, Mediterranean diet score, or energy-adjusted servings per day of food groups comprising the DASH diet and Mediterranean diet scores compared with quintile 1 (reference) in the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging (n = 3580)1

| Quintile of accordance score and food group |

|||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P2 | P-linear trend3 | P-quintile 5 compared with 1 | |

| DASH and components (multivariable adjusted)4 | |||||||

| DASH | 0.35 ± 0.29 | 0.68 ± 0.29 | 0.96 ± 0.29 | 0.97 ± 0.29 | 0.0031 | 0.0001 | 0.0009 |

| Whole grains | 1.32 ± 0.29 | 1.02 ± 0.29 | 0.78 ± 0.29 | 1.19 ± 0.29 | <0.00015 | 0.00545 | <0.00015 |

| Nuts and legumes | 0.80 ± 0.29 | 1.11 ± 0.29 | 1.24 ± 0.29 | 1.22 ± 0.29 | <0.00015 | <0.00015 | <0.00015 |

| Fruit | 0.56 ± 0.29 | 0.89 ± 0.29 | 0.66 ± 0.29 | 0.30 ± 0.29 | 0.0232 | 0.2921 | 0.3002 |

| Vegetables | 0.67 ± 0.29 | 1.17 ± 0.29 | 0.70 ± 0.29 | 0.69 ± 0.29 | 0.00245 | 0.0371 | 0.0188 |

| Red and processed meat | −0.02 ± 0.29 | 0.03 ± 0.29 | −0.35 ± 0.29 | −0.18 ± 0.29 | 0.6403 | 0.2796 | 0.5286 |

| Low-fat dairy | −0.13 ± 0.29 | 0.64 ± 0.29 | 0.42 ± 0.29 | 0.41 ± 0.29 | 0.0414 | 0.0369 | 0.1644 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.33 ± 0.29 | 0.18 ± 0.29 | 0.39 ± 0.29 | −0.11 ± 0.29 | 0.3575 | 0.7899 | 0.6969 |

| Sodium | 0.47 ± 0.29 | 0.70 ± 0.29 | 0.77 ± 0.29 | 0.41 ± 0.29 | 0.0673 | 0.0862 | 0.1532 |

| Mediterranean and components (multivariable adjusted)4 | |||||||

| Mediterranean | 0.68 ± 0.29 | 0.62 ± 0.29 | 0.83 ± 0.29 | 0.94 ± 0.29 | 0.0149 | 0.0022 | 0.0014 |

| All grains | 0.39 ± 0.29 | 0.53 ± 0.29 | 0.74 ± 0.29 | 0.47 ± 0.29 | 0.1328 | 0.0466 | 0.1008 |

| Legumes | 0.47 ± 0.29 | 0.57 ± 0.28 | 1.32 ± 0.29 | 1.16 ± 0.29 | <0.00015 | <0.00015 | <0.00015 |

| Fruit | 0.56 ± 0.29 | 0.89 ± 0.29 | 0.66 ± 0.29 | 0.30 ± 0.29 | 0.0232 | 0.2921 | 0.3002 |

| Vegetables | 0.67 ± 0.29 | 1.17 ± 0.29 | 0.70 ± 0.29 | 0.69 ± 0.29 | 0.00275 | 0.0308 | 0.0142 |

| Meat and meat products | 0.27 ± 0.29 | 0.14 ± 0.29 | −0.15 ± 0.29 | 0.15 ± 0.29 | 0.6396 | 0.8418 | 0.6199 |

| Fish | 0.41 ± 0.29 | 0.54 ± 0.29 | −0.01 ± 0.28 | 0.05 ± 0.29 | 0.1732 | 0.6422 | 0.8483 |

| Full-fat dairy | 0.60 ± 0.29 | 0.55 ± 0.29 | 0.51 ± 0.29 | −0.41 ± 0.29 | 0.00085 | 0.1696 | 0.1529 |

| Ratio of MUFAs to SFAs | 0.19 ± 0.29 | 0.48 ± 0.29 | 0.37 ± 0.29 | 0.30 ± 0.29 | 0.5124 | 0.2192 | 0.2902 |

All values are means ± SEs. DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

Significance of the F value was determined by using type 3 tests of fixed effects; the variable representing the quintile score was entered into the model in the class statement.

Significance of the F value was determined by using type 3 tests of fixed effects; the variable representing the quintile scores was entered into the model as a continuous variable.

The multivariable model included the following covariates: age, sex, education, BMI, frequency of moderate physical activity, multivitamin and mineral supplement use, history of drinking and smoking, and history of diabetes, heart attack, and stroke.

P values remained significant at a type I error rate for statistical significance of 0.05 after applying a Bonferroni correction (0.05 ÷ 8 = 0.0063), which adjusted for the 8 tests run for different food components of the DASH and Mediterranean diet scores.

All prospective analyses were conditioned on dementia-free survival. Nearly all participants (98%) were followed up with a 3MS evaluation or determined to be lost to dementia or death. A complete 3MS assessment and plausible dietary assessment were available from 3530 participants at the baseline assessment (1995–1996). In addition, complete 3MS assessments were available from 2740 participants the 1998–99 examination, 1904 participants in the 2002–2003 examination, and 1255 participants in the 2005–2006 examination. A complete-case analysis was used in all multivariable models; 6.6% of observations (235 of 3580) were excluded because data for one or more of the covariates included in the multivariable models was missing.

RESULTS

The DASH diet score and Mediterranean diet score were positively correlated (r = 0.62, P value ≤0.001), and 53% (n = 383) of subjects in the highest quintile of the DASH score were also in the highest quintile of the Mediterranean score. Participants in the highest quintile of DASH or Mediterranean diet scores were more likely to be women and more educated, physically active, and likely to take a multivitamin and mineral dietary supplement than were subjects in lower quintiles of either score (Tables 2 and 3). Participants in the highest quintile of the DASH or Mediterranean diet scores consumed less total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol than did subjects in the lowest quintile of either diet score. An increasing quintile of Mediterranean but not DASH diet accordance scores was associated with increasing omega-3 fatty acid intake. Increasing quintiles of DASH and Mediterranean scores were associated with decreasing rates of smoking and alcohol intake. Subjects in the highest quintile of either accordance score consumed more of most micronutrients except for zinc than did subjects in lower quintiles. The pattern of calcium intake was different between the 2 diet scores; no differences were observed across quintiles of the Mediterranean diet score (P = 0.057), but calcium intake was higher in upper compared with lower quintiles of the DASH score (P < 0.001).

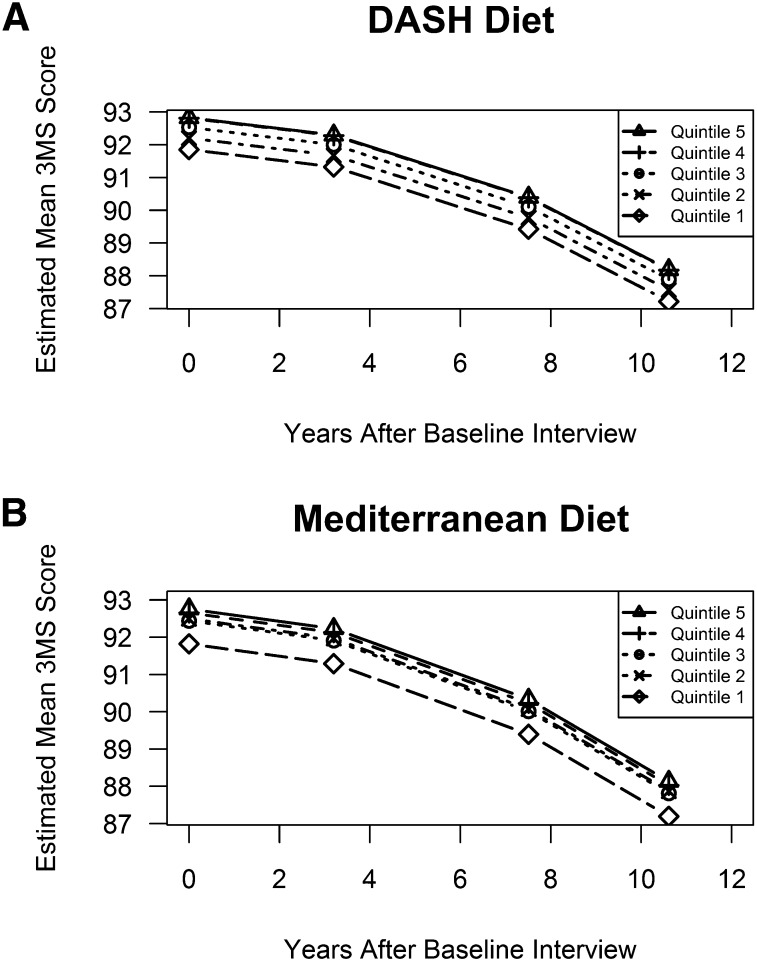

In mixed-effects linear regression models that included age and sex, an increasing quintile of both the DASH and Mediterranean diet scores was associated with higher mean 3MS scores at the baseline interview (Table 4). Within each quintile of the DASH and Mediterranean diet scores, the mean 3MS decreased over the 11 y of follow-up and the relative differences in mean 3MS score between quintiles of each diet score were maintained over the 11 y of follow-up (P from the likelihood ratio test for the time × quintile and time squared × quintile interaction = 0.34 and 0.64, respectively, for the DASH die score and 0.28 and 0.37 respectively, for the Mediterranean diet score). The lack of statistical significance for the time × quintile and time squared × quintile score interactions indicated that the differences in 3MS scores between quintiles of both DASH and Mediterranean scores were consistent over time (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Mean changes in 3MS scores across increasing quintiles of DASH diet accordance scores (A) and Mediterranean diet accordance scores (B) (quintile 1, time 0 = reference) over 11 y of observation in the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging (n = 3580). The multivariable model included the following covariates: age, sex, education, BMI, frequency of moderate physical activity, multivitamin and mineral supplement use, history of drinking and smoking, and history of diabetes, heart attack, and stroke. Significance of the F value was determined from the type 3 tests of fixed effects (P = 0.001); the variable that represents quintile scores was entered into the model as a continuous variable (P-linear trend < 0.001). DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

In models that controlled for age and sex, participants in the highest quintile of the DASH diet score scored 1.93 points higher on the baseline assessment than did subjects in the lowest quintile of the DASH diet score (P < 0.001). Similarly, participants in the highest quintile of the Mediterranean diet score scored 1.41 points higher on the baseline assessment than did subjects in the lowest quintile of the Mediterranean diet score (P < 0.001). In models that also included covariates for the level of education, low BMI (<18.5), frequency of moderate physical activity, multivitamin mineral use, history of smoking and drinking, and myocardial infarction, stroke, and diabetes, participants in the highest quintile of the DASH diet score scored an average of 0.97 points higher than did subjects in the lowest quintile (P = 0.001) (Table 4). In the corresponding model for Mediterranean diet score quintiles, the difference was 0.94 (P = 0.001). In these multivariable models, subjects in the highest 3 quintiles (quintiles 3–5) of the DASH diet score had 3MS scores 0.68, 0.96, and 0.97 points higher, respectively, at the baseline interview than those of subjects in the lowest (first) quintile of the DASH diet score (P = 0.019, 0.001, 0.001, respectively; P-trend < 0.001). Subjects in the second quintile had a 3MS score that was not significantly different from that of subjects in the lowest quintile (P = 0.224). Similarly, subjects in the highest 4 quintiles (quintiles 2–5) of the Mediterranean diet score had 3MS scores 0.68, 0.62, 0.83, and 0.94 points higher at the baseline interview than those of subjects in the lowest (first) quintile of the Mediterranean diet score (P = 0.018, 0.032, 0.004, and 0.001, respectively; P-trend = 0.0022). These differences were maintained over time, and the rates of 3MS change over time were not significantly different across the quintile groups (Figure 1).

Similar mixed-effects multivariable linear regression models were used to explore individual effects of food and nutrient components that made up the DASH and Mediterranean diet scores on 3MS scores over time (Table 4). After a Bonferroni correction was applied to the level of significance, increasing quintiles of whole grains (a component of both DASH and Mediterranean diets), nuts and legumes (combined; component of the DASH diet), and legumes only (component of the Mediterranean diet) were each independently associated with higher 3MS scores (P-linear trend = 0.0054, <0.0001, and <0.0001, respectively). No similar trends were observed for other single food or nutrient components of the DASH or Mediterranean diet accordance scores (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Cognitive decline is an early manifestation of dementia, including AD, and, thus, is a statistically powerful study outcome in cohort studies with repeated measures (38–40). compared with lower levels of accordance, higher accordance to the DASH and Mediterranean-style diets were both similarly associated with higher cognitive function at baseline in elderly men and women in the CCMS. These differences were similar to being ∼3 y younger in age and were maintained across 11 y of follow-up. A higher consumption of whole grains and nuts and legumes were each independently associated with higher cognitive scores at the baseline assessment.

The pioneering Seven Countries Study by Keys et al (41) in the 1950s to 1960s identified the traditional diet on the Greek island of Crete in the southern Mediterranean Sea as a model for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Mediterranean dietary patterns have been associated with reduced risk of overall mortality and a broad range of chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative disease (42). The importance of Mediterranean-type dietary patterns in maintaining cognitive function is uncertain because, in some studies, it has shown a protective effect (10–15, 43, 44), whereas in other studies, it has not shown a protective effect (16–19).

Diets in the Mediterranean region are diverse as are the definitions of Mediterranean diets used in scientific studies (7), and the concept of a Mediterranean diet as a unified, meaningful regional and global dietary pattern has been seriously questioned (20, 21). Bere and Brug (20) pointed out that the associations with positive health outcomes in studies that used Mediterranean dietary pattern scores were not necessarily based on Mediterranean foods, both in studies within and outside the Mediterranean region, and argued that it seems appropriate to promote local diets with dietary variety, minimal processing, cultural diversity, and heritage rather than promote the idea of a global Mediterranean diet. We agree that a pitfall of the definition, evaluation, and endorsement of dietary patterns for health promotion is that the patterns are artificial constructs that may become stereotypes that obscure the recognition of healthy dietary patterns in other regions and cultures.

The DASH diet substantially reduced blood pressure in hypertensive and normotensive individuals in clinical trials (22) and is recommended in the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2010) (23). A high accordance to DASH-style diets has been associated with lower risk of CHD and stroke in middle-aged women during 24 y of follow-up (35) and lower risk of heart failure in women in the Swedish Mammography Cohort (45). Because of the association between hypertension and subsequent cognitive decline and dementia, it is plausible that the DASH diet may reduce risk of cognitive decline by lowering blood pressure in hypertensive individuals. The DASH diet has also been associated with reduced risk of other chronic conditions and may have beneficial effects on brain health via diverse mechanisms unrelated to blood pressure (46–50). Few previous studies have examined associations between DASH dietary accordance and cognitive function in the elderly (51).

Our findings that 2 food groups (ie, whole grains and nuts and legumes) may be primarily responsible for the similar protective associations of DASH and Mediterranean dietary patterns may provide a simple path for linking public-health nutrition recommendations with agricultural policy around the globe. For example, all traditional and industrialized agricultural economies are based on cereal grains, and more attention to the health hazards of a low intake of whole grains and high intake of refined grains is warranted.

Whole grain is a component of the DASH diet but is not consistently differentiated from refined grains in Mediterranean-style diet scores. For example, Trichopoulou et al (37) included refined grains such as pasta, starches, crisp bread, breakfast cereals, biscuits, pastry, and other cereal products in their Mediterranean diet score. No previous study, to our knowledge, has examined associations between whole-grain consumption and cognitive decline or dementia apart from its contribution to a dietary pattern. Strong epidemiologic evidence supports associations between a high consumption of whole-grain foods and lower risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes (52).

In addition, nuts and legumes, which are common components of the DASH and Mediterranean diet scores, were observed to be beneficial for cognition. Nuts and legumes share similar nutrient profiles in that both are high in fiber, protein, unsaturated fatty acids, folic acid, other essential micronutrients, and a variety of phytochemicals. Nut consumption was associated with decreased prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome in adult participants in the 1999–2004 NHANES (34). Legumes have been shown to reduce the concentration of blood cholesterol in randomized trials (35). To our knowledge, no previous study has reported on the independent effects of nuts or legume consumption and cognition in the elderly.

The CCMS, which is a large population-based, prospective study of predominantly non-Hispanic white elderly men and women from a geographically defined area where the median life expectancy exceeds that of the US population by 10–12 y (53), has a high rate of participation, which is a factor that is known to reduce bias in observational studies of the aged (54). An additional unique feature of the Cache cohort is that 90% of the participants are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (or Mormon) religion. This religion discourages its members from drinking alcohol or smoking, and low smoking and drinking rates were observed in participants. Because of the low rates of alcohol consumption in this cohort, alcohol was not included in the Mediterranean adherence score and this may have limited the generalizability of our findings regarding this score (and this may make comparisons between the Mediterranean score used in the current study and other studies difficult). In addition, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints lifestyle likely contributes to the increased longevity and low burden of chronic disease (55), especially in the oldest-old, which is an advantage for studying conditions or diseases of the aged; however, these associations should also be assessed in other aging populations with a higher burden of chronic disease.

A weakness of this and other observational studies was that the purported effects of dietary factors may have been confounded by associated healthy lifestyle factors; this weakness applies to studies of single nutrients, single foods, and dietary patterns. For example, participants with high dietary accordance scores were more educated and more likely to be physical active than were participants with low dietary accordance scores. We controlled for these and other characteristics that were related to both diet and cognition, but there may have been other unmeasured characteristics or residual confounding that may have biased our results toward the null. However, an alternative hypothesis was that the effects related to diet reflected lifelong differences in healthy lifestyles that included a healthy diet. Little is known about associations between patterns of lifestyles and risk of cognitive decline and dementia (56). In addition, we observed cognitive benefits of diet at the baseline assessment that were maintained but not modified over the time of these observations. Our findings could not distinguish whether the observed differences in cognitive function were because of preexisting differences that may have been confounded with the diet or progression of cognitive decline that may have been modified by diet if the cohort were to have been followed for a longer period of time.

In conclusion, a higher accordance to each of DASH or Mediterranean-style diets was similarly associated with higher baseline 3MS scores that were maintained for 11 y of observation in predominately non-Hispanic white elderly men and women of the CCMS. In analyses that examined individual food-group contributions, whole grains (a DASH diet component) and nuts and legumes (common components of DASH and Mediterranean-style diet scores) provided similar benefits as did diet scores that included 8 food components. The promotion of the consumption of whole grains and legumes and nuts may provide a dietary strategy aimed at a cognitive benefit that is adaptable to diverse cultures and regions around the globe.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—HW, RGM, JTT, MCN, and KAW-B: contributed to the design of the study; HW, AB, AC, AQ, and CC: contributed to the analysis of data; and all authors: contributed to the writing and editing of the final manuscript. None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AD, Alzheimer disease; CCMS, Cache County Memory Study; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moschetti K, Cummings PL, Sorvillo F, Kuo T. Burden of Alzheimer's disease-related mortality in the United States, 1999-2008. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1509–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1337–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillette Guyonnet S, Abellan Van Kan G, Andrieu S, Barberger Gateau P, Berr C, Bonnefoy M, Dartigues JF, de Groot L, Ferry M, Galan P, et al. IANA task force on nutrition and cognitive decline with aging. J Nutr Health Aging 2007;11:132–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol 2002;13:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keys A. Coronary heart disease–the global picture. Atherosclerosis 1975;22:149–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keys A. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brill JB. Mediterranean diet. Am J Lifestyle Medicine 2008;3:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, Drescher G, Ferro-Luzzi A, Helsing E, Trichopoulos D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;61(suppl):1402S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Mediterranean diet, Alzheimer disease, and vascular mediation. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1709–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Mayeux R, Stern Y. Mediterranean diet and Alzheimer disease mortality. Neurology 2007;69:1084–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Mayeux R, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Luchsinger JA. Mediterranean diet and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2009;66:216–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Schupf N, Brickman AM, Cosentino S, Tang MX, Stern Y. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2009;302:627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tangney CC, Kwasny MJ, Li H, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Morris MC. Adherence to a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern and cognitive decline in a community population. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:601–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye X, Scott T, Gao X, Maras JE, Bakun PJ, Tucker KL. Mediterranean diet, healthy eating index 2005, and cognitive function in middle-aged and older puerto rican adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:276–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Féart C, Samieri C, Rondeau V, Amieva H, Portet F, Dartigues JF, Scarmeas N, Barberger-Gateau P. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet, cognitive decline, and risk of dementia. JAMA 2009;302:638–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Cerhan JR, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Ivnik RJ, Boeve BF, O'Connor HM, et al. Vegetables, unsaturated fats, moderate alcohol intake, and mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010;29:413–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ. The Mediterranean diet is not related to cognitive change in a large prospective investigation: the PATH Through Life study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:635–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vercambre MN, Grodstein F, Berr C, Kang JH. Mediterranean diet and cognitive decline in women with cardiovascular disease or risk factors. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:816–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesse-Guyot E, Andreeva VA, Lassale C, Ferry M, Jeandel C, Hercberg S, Galan P. Mediterranean diet and cognitive function: a French study. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bere E, Brug J. Is the term 'Mediterranean diet’ a misnomer? Public Health Nutr 2010;13:2127–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serra-Majem L, Trichopoulou A, Ngo de la Cruz J, Cervera P, Garcia Alvarez A, La Vecchia C, Lemtouni A, Trichopoulos D. Does the definition of the Mediterranean diet need to be updated? Public Health Nutr 2004;7:927–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Vogt TM, Cutler JA, Windhauser MM, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. USDA. 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Updated 15 August 2013. Available from: http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/dietaryguidelines.htm (cited 8 Sept 2013).

- 24.Novak V, Hajjar I. The relationship between blood pressure and cognitive function. Nature reviews. Cardiology 2010;7:686–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Plassman BL, Norton MC, Wyse BW, Breitner JC. An adaptation of the modified mini-mental state examination: analysis of demographic influences and normative data: the cache county study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2002;15:28–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLellan T, Jorde LB, Skolnick MH. Genetic distances between the Utah Mormons and related populations. Am J Hum Genet 1984;36:836–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wengreen HJ, Munger RG, Corcoran CD, Zandi P, Hayden KM, Fotuhi M, Skoog I, Norton MC, Tschanz J, Breitner JC, et al. Antioxidant intake and cognitive function of elderly men and women: the Cache County Study. J Nutr Health Aging 2007;11:230–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng EL, Chui HC, Schneider LS, Metzger LE. Alzheimer's dementia: performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987;55:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Skoog I, West N, Norton MC, Wyse BW, Nickles R, Breitner JC. Dementia diagnoses from clinical and neuropsychological data compared: the Cache County study. Neurology 2000;54:1290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munger RG, Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Kaye SA, Sellers TA. Dietary assessment of older Iowa women with a food frequency questionnaire: nutrient intake, reproducibility, and comparison with 24-hour dietary recall interviews. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136:192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogt TM, Appel LJ, Obarzanek E, Moore TJ, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Cutler JA, Windhauser MM, et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension: rationale, design, and methods. DASH Collaborative Research Group. J Am Diet Assoc 1999;99(suppl):S12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellen PB, Gao SK, Vitolins MZ, Goff DC., Jr Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Folsom AR, Parker ED, Harnack LJ. Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linn RT, Wolf PA, Bachman DL, Knoefel JE, Cobb JL, Belanger AJ, Kaplan EF, D'Agostino RB. The 'preclinical phase’ of probable Alzheimer's disease. A 13-year prospective study of the Framingham cohort. Arch Neurol 1995;52:485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Small BJ, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Backman L. The course of cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer disease: three- and 6-year follow-up of a population-based sample. Arch Neurol 2000;57:839–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Beckett LA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Fox JH, Bach J. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology 2002;59:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keys A. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Tang MX, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 2006;59:912–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Psaltopoulou T, Kyrozis A, Stathopoulos P, Trichopoulos D, Vassilopoulos D, Trichopoulou A. Diet, physical activity and cognitive impairment among elders: the EPIC-Greece cohort (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition). Public Health Nutr 2008;11:1054–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levitan EB, Wolk A, Mittleman MA. Consistency with the DASH diet and incidence of heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:851–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liese AD, Nichols M, Sun X, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Haffner SM. Adherence to the DASH Diet is inversely associated with incidence of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1434–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi T, Azizi F. Beneficial effects of a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2823–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor EN, Fung TT, Curhan GC. DASH-style diet associates with reduced risk for kidney stones. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:2253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dixon LB, Subar AF, Peters U, Weissfeld JL, Bresalier RS, Risch A, Schatzkin A, Hayes RB. Adherence to the USDA food guide, DASH eating plan, and Mediterranean dietary pattern reduces risk of colorectal adenoma. J Nutr 2007;137:2443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin PH, Ginty F, Appel LJ, Aickin M, Bohannon A, Garnero P, Barclay D, Svetkey LP. The DASH diet and sodium reduction improve markers of bone turnover and calcium metabolism in adults. J Nutr 2003;133:3130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Craighead L, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Browndyke JN, Strauman TA, Sherwood A. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension 2010;55:1331–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jonnalagadda SS, Harnack L, Liu RH, McKeown N, Seal C, Liu S, Fahey GC. Putting the whole grain puzzle together: health benefits associated with whole grains–summary of American Society for Nutrition 2010 Satellite Symposium. J Nutr 2011;141:1011S–22S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray CUS. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norton MC, Breitner JC, Welsh KA, Wyse BW. Characteristics of nonresponders in a community survey of the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:1252–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Enstrom JE. Cancer mortality among Mormons. Cancer 1975;36:825–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norton MC, Dew J, Smith H, Fauth E, Piercy KW, Breitner JC, Tschanz J, Wengreen H, Welsh-Bohmer K. Lifestyle behavior pattern is associated with different levels of risk for incident dementia and Alzheimer's disease: the Cache County study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]