Abstract

Objectives

In resource-constrained settings, tuberculosis (TB) is a common opportunistic infection and cause of death in HIV-infected persons. TB may be present at the start of antiretroviral therapy (ART), but it is often under-diagnosed. We describe approaches to TB diagnosis and screening of TB in ART programs in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods and findings

We surveyed ART programs treating HIV-infected adults in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America in 2012 using online questionnaires to collect program-level and patient-level data. Forty-seven sites from 26 countries participated. Patient-level data were collected on 987 adult TB patients from 40 sites (median age 34.7 years; 54% female). Sputum smear microscopy and chest radiograph were available in 47 (100%) sites, TB culture in 44 (94%), and Xpert MTB/RIF in 23 (49%). Xpert MTB/RIF was rarely available in Central Africa and South America. In sites with access to these diagnostics, microscopy was used in 745 (76%) patients diagnosed with TB, culture in 220 (24%), and chest X-ray in 688 (70%) patients. When free of charge culture was done in 27% of patients, compared to 21% when there was a fee (p = 0.033). Corresponding percentages for Xpert MTB/RIF were 26% and 15% of patients (p = 0.001). Screening practices for active disease before starting ART included symptom screening (46 sites, 98%), chest X-ray (38, 81%), sputum microscopy (37, 79%), culture (16, 34%), and Xpert MTB/RIF (5, 11%).

Conclusions

Mycobacterial culture was infrequently used despite its availability at most sites, while Xpert MTB/RIF was not generally available. Use of available diagnostics was higher when offered free of charge.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most common opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings and associated with high mortality in patients who start antiretroviral combination therapy (ART) [1], [2]. In high TB-incidence settings, TB may frequently be present at ART initiation, but not always diagnosed, and contributes significantly to mortality in the first weeks and months of ART [3], [4]. One risk factor for early mortality is an unmasking or paradoxical immune reconstitution syndrome that may occur after ART start, particularly in severely immunosuppressed patients [1], [5]–[8].

The overall incidence of TB is substantially reduced with long-term ART in both adults and children [2], [9]–[11] but additional interventions are needed to control TB in HIV-infected patients including screening, improved diagnosis and preventive therapy [12]–[14]. TB screening and diagnosis before starting ART is important, since the initiation of ART shortly after the initiation of TB treatment improves survival, particularly in patients with low CD4 cell counts [15]–[17].

In a survey of 15 ART programs in 12 countries in Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America, as well as Asia, we previously showed that the capacity of programs to diagnose TB was often limited in 2008 [18]. Since then, new diagnostic tools for rapid TB diagnosis have been introduced and have shown promising results [19], [20]. In 2012, we undertook a large scale survey on the integration of TB and HIV services, diagnostic, screening, preventive and treatment practices within the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) collaboration. Here, we report the results on the availability and use of TB diagnostics across adult ART programs in low- and middle-income countries, using both program-level and patient-level data.

Methods

IeDEA includes networks of ART programs in low- and middle-income countries from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Central and South America, as well as North America [21]–[23]. Data are collected at each site as part of routine monitoring at program enrollment and each follow-up visit. We surveyed ART sites in low- and middle-income countries participating in IeDEA across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Central and South America between March 1 and July 1, 2012. A total of 71 sites treating adults or children were invited and 58 sites (81.7%) participated, including 11 pediatric sites treating children only. See File S1 and Table S1 in Supporting Information for a list of investigators and sites.

Data collection

Representatives from participating IeDEA regions and the TB and pediatric working groups of IeDEA developed this project. The survey was written in English, translated into French and Spanish, and pilot-tested in both languages. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools (see https://redcap.vanderbilt.edu/) [24]. The survey consisted of three components: Section A was an online questionnaire on integration of services, diagnostic, screening, preventive and treatment practices related to TB at the sites; Section B included eight clinical scenarios on TB and HIV management to assess the practices of treating clinicians; and Section C requested routinely collected data on consecutive TB patients seen during the study period.

Section A was completed by local data managers or medical staff. Data collected included site characteristics (level of care, urban or rural setting, number of HIV patients actively followed-up, number of TB cases seen), diagnostic and screening practices, infection control measures, treatment schemes, prevention and prophylaxis practices, integration of HIV and TB care, costs to patients and TB case definitions. Availability was assessed as access to the provider on site, within 5 km, within 10 km, within 20 km, within 30 km, within 40 km, within 50 km, more than 50 km, or not available. In Section B, treating physicians and clinical officers at the sites were asked to address clinical scenarios for hypothetical TB patients presenting at their clinic (Table S2). Treating physicians were instructed that the answers should reflect current practices at their treatment program and not necessarily the best practice available. Sections A and B consisted of one questionnaire per site. In Section C, we requested data on HIV-infected TB patients consecutively seen from the start of the study period on March 1 through to July 1, 2012, up to a maximum of 50 patients per site. TB cases were defined based on the local case definition; all received anti-TB treatment. Collected data included age, sex, pregnancy status at time of TB diagnosis, date of enrollment into HIV care, date of TB diagnosis, start date of TB treatment, prescribed TB regimen, start date of ART, CD4 cell count, WHO clinical stage at ART start, date of any previous TB episode, type of screening, type of episode (new case, relapse, treatment after failure, etc.), disease manifestation, sputum microscopy result, culture result, nucleic acid amplification test result, clinical signs and symptoms (coughing, night sweats, fever, weight loss), use of tuberculin skin testing (TST) and isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT). Seven sites from four regions (Asia-Pacific, Caribbean-Central-South America, Central Africa, Southern Africa) did not contribute individual-level patient data because the data collection was not covered by the local IRB approval (four sites), or because of logistical reasons (three sites).

Statistical analyses

The present analysis included ART programs treating patients aged 16 years or older, and focused on TB diagnostics and screening practices. Descriptive statistics were used to compare characteristics of sites and TB patients. Variables of interest included program-level characteristics (such as level of care, setting, cumulative HIV cohort size, or availability of diagnostics), clinical decision making using hypothetical clinical scenarios (such as decision to conduct sputum smear microscopy, culture, or chest X-ray), and individual-level patient data (such as age, sex, WHO clinical stage, on ART or not when TB treatment started, use of sputum smear microscopy, culture, Xpert MTB/RIF, or chest X-ray to diagnose TB). We distinguished between the availability of diagnostics (“access”) and how diagnostic tools were used at the patient level at sites with access to the tools (“use”). We assumed that there was access to a tool if it was available on or off site. We used χ2 tests or Fisher's exact tests to assess differences between groups in binary variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Results are presented overall and stratified by IeDEA region. All analyses were performed in Stata version 11.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Data sharing statement

The data held by the IeDEA consortium are available to other investigators, based on a concept note describing the planned analysis which was approved by the regional Steering Groups and, if analyses involve several regions, by the Executive Committee of IeDEA. Further details are provided at www.iedea.org/welcome-to-iedea/working-groups/concept-sheets/iedea-multi-region-concepts-principles-and-procedures.

Ethics statement

Data were collected through IeDEA cohorts. Ethics committees and/or Institutional Review Boards in all host countries approved the collection and transfer of anonymized data (see File S2 in Supporting Information for a complete list). Where requested per local regulations informed consent was provided. In addition, the Vanderbilt University Health Science Committee, Nashville, Tennessee (USA), the Ethics Committee of the University of Bern (Switzerland), and the University of Cape Town (South Africa) approved the analyses of these observational data for this specific project.

Results

Program and patient characteristics

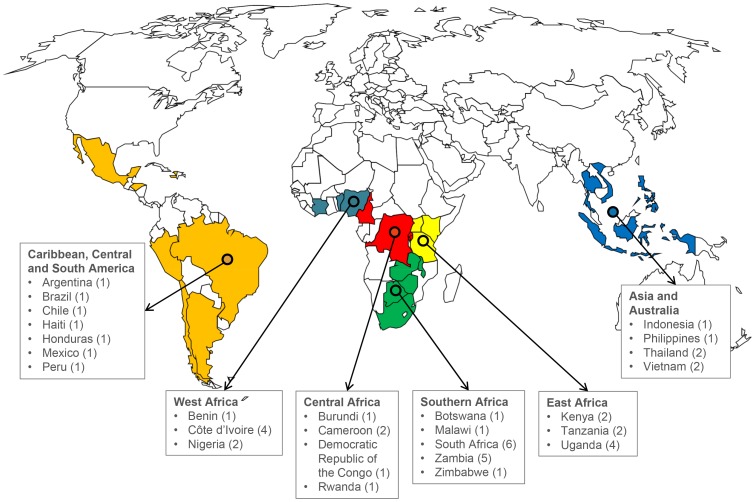

Forty-seven ART sites from 26 countries treating adult HIV patients were included (see map in Figure 1 and list in Table S1). These sites treat more than 250,000 HIV-infected adult patients, with almost 18,000 new TB cases diagnosed each year. Twenty-four (51.1%) sites were tertiary care centers and 15 (31.9%) were treating adults only (Table 1). Twenty-eight (59.6%) sites had a specialized TB clinic or ward on site with dedicated staff, nine (19.1%) sites had no specialized clinic, and 10 (21.3%) sites referred TB patients elsewhere. Data on 987 adult TB patients from 40 sites were available. In seven sites, investigators were unable to collect patient data for this survey or no TB cases were seen during the study period. The median age of TB patients was 34.7 years (interquartile range [IQR] 29.4–40.9) and 442 patients (44.8%) were female. The median CD4 cell count at ART initiation was 127 cells/mm3 (IQR 42–250), and 128 (13.0%) patients had a history of previous TB. The median time between TB treatment and ART initiation was 37 days (IQR 15–124). The characteristics of patients are presented in Table S3.

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of the 47 ART programs the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) collaboration, which treat adults in lower income countries and participated in the survey project.

The regions correspond to the IeDEA regions. Countries with at least one site completing Section A of the questionnaire are shown. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of adult ART programs included in the analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of 47 adult ART programs from lower income countries and 987 adult patients seen during the study period in the programs participating in the study.

| Characteristic | All | Asia Pacific | Caribbean-Central-South America | Central Africa | East Africa | Southern Africa | West Africa |

| ART program characteristics | |||||||

| Number of sites, n | 47 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 14 | 7 |

| Number of countries, n | 26 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Setting, n (%) | |||||||

| Urban | 38 (80.8) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 5 (100) | 4 (50.0) | 10 (71.4) | 6 (85.7) |

| Peri-urban | 7 (14.9) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | |||

| Rural | 2 (4.3) | 2 (25.0) | |||||

| Level of care, n (%) | |||||||

| Primary | 15 (31.9) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (25.0) | 10 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| Secondary | 8 (17) | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (40) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) |

| Tertiary | 24 (51.1) | 5(83.3) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (60) | 5 (62.5) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (42.8) |

| Treating adults and children, n (%) | |||||||

| Adults and children | 32 (68.1) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (100) | 6 (75.0) | 12 (85.7) | 5 (71.4) |

| Adults only | 15 (31.9) | 5 (8.33) | 4 (57.1) | 0 | 2 (25.0) | 2(14.3) | 2 (28.6) |

| Cost model | |||||||

| Full payment by the patient | 2 (4.3) | 2 (28.6) | |||||

| Cost sharing (partial payment) | 19 (40.4) | 3 (50) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (80) | 2 (25) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (71.4) |

| Available at no cost for the patient | 23 (48.9) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (20) | 6 (75) | 9 (64.3) | 0 |

| Other | 3 (6.4) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0 | |||

| Cumulative number of patients enrolled 1, n | 251,377 | 8,861 | 19,029 | 11,977 | 103,954 | 76,767 | 30,789 |

| New TB cases per year, n | 17,748 | 296 | 1,693 | 606 | 2,134 | 12,378 | 641 |

| Pre-ART TB (on average) 2, median, % | 22.9 | 26 | 33.9 | 37.8 | 10.4 | 18.9 | 22.7 |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||

| No. of patients | 987 | 35 | 71 | 47 | 255 | 481 | 98 |

| Age at start of ART, median (IQR), years | 34.7 (29.4–41) | 32.7 (28.6–37.2) | 34 (27.3–42.4) | 37.1 (30.1–44.6) | 35.2 (29.3–42.3) | 34.4 (29.1–39.6) | 36.2 (31.2–42.2) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 442 (44.8) | 8 (22.9) | 29 (40.8) | 23 (40.8) | 119 (46.7) | 210 (43.7) | 53 (54.1) |

| Site of disease, n (%) | |||||||

| Pulmonary | 685 (69.4) | 24 (68.6) | 56 (78.9) | 23 (48.9) | 198 (77.6) | 328 (68.2) | 56 (57.1) |

| Extrapulmonary | 293 (29.7) | 11 (31.4) | 12 (16.9) | 20 (42.6) | 57 (22.3) | 152 (31.6) | 41 (41.8) |

| Unknown | 9 (0.9) | 0 | 3 (4.2) | 4 (8.5) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (1) |

| Type of TB patient, n (%) | |||||||

| New case | 863 (87.4) | 25 (71.4) | 60 (84.6) | 37 (78.7) | 236 (92.6) | 413 (85.9) | 92 (93.9) |

| Relapse | 78 (7.9) | 5 (14.3) | 6 (8.4) | 1 (2.1) | 13 (5.1) | 47 (9.8) | 6 (6.1) |

| Treatment after default | 11 (1.1) | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 3 (1.2) | 6 (1.2) | 0 |

| Other | 23 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 9 (19.1) | 1 (0.4) | 13 (2.7) | 0 |

| CD4 cell count (cells/µl) 1 | |||||||

| At time of ART start, median (IQR) | 127 (42–250) | 58 (21–186) | 192.5 (71–355) | 148 (49–336) | 105 (31–271) | 113 (42–217) | 163.5 (73–281) |

| Missing observations, n (%) | 158 (16.1) | 2 (5.7) | 13 (18.3) | 12 (25.6) | 43 (16.9) | 84 (17.5) | 4 (4.1) |

| WHO clinical stage 1, n (%) | |||||||

| I and II | 58 (6.3) | 0 | 3 (4.6) | 1 (2.3) | 19 (7.5) | 15 (3.5) | 20 (21.0) |

| III and IV | 863 (93.7) | 35 (100) | 63 (94.4) | 42 (97.7) | 234 (92.5) | 414 (96.5) | 75 (79.0) |

| Missing observations, n | 66 (6.7) | 0 | 5 (7) | 4 (8.6) | 2 (0.8) | 52 (10.8) | 3 (3.1) |

| Previous history of TB, n (%) | 180 (18.2) | 0 | 49 (69) | 11 (23.4) | 41 (16.1) | 56 (11.6) | 23 (23.5) |

| Delay between TB diagnosis and TB treatment, n (%) | |||||||

| Within 2 days | 810 (82.1) | 23 (65.7) | 60 (84.5) | 47 (100) | 217 (85.1) | 401 (83.4) | 62 (63.3) |

| More than 2 days | 177 (17.9) | 12 (34.3) | 11 (15.5) | 38 (14.9) | 80 (16.6) | 36 (36.7) | |

| Median delay between TB treatment and ART 2, days, (IQR) | 37 (15–124) | 18.5 (11–30) | 17 (14–68) | 33 (27–127) | 63 (31–150) | 41.5 (17–129) | 36 (32–85) |

| TB treatment before enrolment to ART | 388 (39.1) | 26 (74.3) | 41 (57.7) | 15 (31.9) | 51 (20.0) | 246 (51.1) | 9 (9.2) |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; TB, tuberculosis; SMS: Short Message Service.

followed-up at time of survey.

proportion of adults with previous history of TB before starting ART.

Availability of diagnostics

Sputum smear microscopy and chest X-ray were available at all sites (Table 2). Eighteen (38.3%) sites reported using two sputum samples collected on the spot and early in the morning, 16 (34.0%) used three sputum samples, 12 (25.5%) sites used at least one sputum per patient, and 18 (38.3%) sites used other procedures. Thirty-two sites (68.1%) had conventional chest X-ray and 7 (14.9%) digital X-ray. TST was available in 29 (61.7%) sites. Mycobacterial culture was available in 44 (93.6%) sites (Table 2). The most frequently available culture systems were solid media based culture in 16 sites (36.4%) and liquid culture (MGIT 960, Beckton Dickinson, USA) in 15 sites (34.1%). The semi-automated molecular diagnostic assay Xpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, USA) was available in about half of the sites (23 sites, 48.9%). The average turnaround time for a TB diagnosis was reported to range between 3 and 4 days (median 3 days, range 1–14) in smear-positive cases and 8–9 days in smear-negative cases (median 7 days, range 1–30). Details on the availability and use of diagnostics are presented in Table S4.

Table 2. Program-level characteristics associated with the availability of sputum smear microscopy, culture, chest X-ray, Xpert MTB/RIF, and tuberculin skin testing (TST) in 47 ART programs treating adults in lower income countries.

| Program-level characteristic | Sputum microscopy | Culture | Chest X-ray | Xpert MTB/RIF | TST | ||||||

| n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | ||

| Total | 47 (100) | 44 (93.6) | 47 (100) | 23 (48.9) | 29 (61.7) | ||||||

| IeDEA region | – | 0.63 | – | 0.41 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Asia-Pacific | 6 | 6 (100) | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||||||

| Caribbean-Central-South America | 7 | 7 (100) | 7 | 2 (28.6) | 6 (85.7) | ||||||

| Central Africa | 5 | 4 (80.0) | 5 | 1 (20.0) | 5 (100) | ||||||

| East Africa | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 8 | 4 (50.0) | 2 (25.0) | ||||||

| Southern Africa | 14 | 13 (92.9) | 14 | 9 (64.3) | 4 (28.6) | ||||||

| West Africa | 7 | 7 (100) | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 7 (100) | ||||||

| Setting | – | 0.62 | – | 0.89 | 0.017 | ||||||

| Urban | 38 | 36 (95.7) | 38 | 18 (47.4) | 27 (71.0) | ||||||

| Peri-urban | 7 | 6 (85.7)) | 7 | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) | ||||||

| Rural | 2 | 2 (100) | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||||||

| Level of care | – | 0.71 | – | 0.70 | 0.32 | ||||||

| Primary | 15 | 14 (93.3) | 15 | 7 (46.7) | 7 (46.7) | ||||||

| Secondary | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | ||||||

| Tertiary | 24 | 23 (95.8) | 24 | 13 (54.2) | 17 (70.8) | ||||||

| Treating adults and children | – | 0.22 | – | 0.68 | 0.077 | ||||||

| Adults and children | 15 | 15 (100) | 15 | 8 (53.3) | 12 (80.0) | ||||||

| Adults only | 32 | 29 (90.6) | 32 | 15 (46.8) | 17 (53.1) | ||||||

| Cumulative number of adults enrolled in HIV care 1 | – | 0.65 | – | 0.27 | 0.12 | ||||||

| Below 1,000 | 5 | 5 (100) | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||||||

| 1,001 to 10,000 | 37 | 34 (91.9) | 37 | 16 (43.2) | 25 (67.6) | ||||||

| 10,001 to 20,000 | 5 | 5 (100) | 5 | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | ||||||

| New TB cases per year, n | – | 0.19 | – | 0.74 | 0.014 | ||||||

| Below 100 | 23 | 20 (86.7) | 23 | 10 (43.5) | 19 (82.6) | ||||||

| 100 to 1,000 | 18 | 18 (100) | 18 | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | ||||||

| >1,000 | 6 | 6 (100) | 6 | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | ||||||

ART, antiretroviral treatment; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Chi square tests were used to calculate P values.

followed-up at time of survey.

TST was less frequently available in sites from East and Southern Africa compared to other regions (25% and 28.6%, versus 83.3% to 100%, P = 0.001, Table 2). The availability of all other TB diagnostics varied across regions, but differences did not reach statistical significance. TST was also more frequently available in urban settings compared to peri-urban and rural settings (71.0%, 14.3% and 50.0%; P = 0.017), as well as more frequent in smaller sites with fewer TB cases (82.6% in sites with fewer than 100 TB cases per year, compared to 44.4% and 33.3% in sites with 100 to 1,000 and more than 1,000 cases; P = 0.014).

Use of diagnostics

Overall, sputum microscopy was done in 745 (75.7%) patients, mycobacterial culture in 220 (23.9%), Xpert MTB/RIF in 120 (20.6%), and chest X-ray in 688 (69.7%, Table 3). Results were similar when restricting the analysis to the 642 patients with pulmonary TB: 574 patients (83.8%) had sputum microscopy, 137 (21.3%) mycobacterial culture, 83 (21.0%) Xpert MTB/RIF, and 460 patients (67.1%) had a chest X-ray. In sites where diagnostic tools were available, the geographic region, degree of urbanization, level of care and payment models were associated with their use (Table 3). For example, culture was more frequently used in sites from the Caribbean, Central and South America than in sites from East Africa (66.2% versus 2.5%, P<0.0001). Mycobacterial culture was also more frequently used in urban settings (27.3% in urban settings versus 15.5% in peri-urban and 4.9% in rural settings, P<0.0001).

Table 3. Availability and use of tuberculosis (TB) diagnostics in adult TB patients from 47 ART programs in lower income countries.

| Program-level characteristic | Total | Sputum microscopy | Culture | Chest X-ray | Xpert MTB/RIF | TST | ||||||||||

| Access n | Used n (%) | P value | Access n | Used n (%) | P value | Access n | Used n (%) | P value | Access n | Used n (%) | P value | Access n | Used n (%) | P value | ||

| Total | 987 | 987 | 745 (75.5) | 919 | 220 (23.9) | 987 | 688 (69.7) | 584 | 120 (20.6) | 380 | 39 (10.3) | |||||

| IeDEA region | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||||||

| Asia-Pacific | 35 (3.6) | 35 | 31 (88.6) | 35 | 17 (48.6) | 35 | 33 (94.3) | 21 | 5 (23.8) | 21 | 0 | |||||

| Caribbean-Central-South America | 71 (7.2) | 71 | 61 (85.9) | 71 | 47 (66.2) | 71 | 47 (66.2) | 54 | 10 (18.5) | 71 | 27 (38) | |||||

| Central Africa | 47 (4.8) | 47 | 19 (40.4) | 31 | 3 (9.7) | 47 | 25 (53.2) | 20 | 0 | 47 | 1 (2.1) | |||||

| East Africa | 255 (25.8) | 255 | 212 (83.1) | 244 | 6 (2.5) | 255 | 165 (65.7) | 158 | 3 (1.9) | 49 | 0 | |||||

| Southern Africa | 481 (48.7) | 481 | 353 (72.9) | 440 | 143 (32.5) | 481 | 341 (70.9) | 300 | 101 (33.7) | 94 | 3 (3.2) | |||||

| West Africa | 98 (9.9) | 98 | 71 (72.4) | 98 | 4 (4.1) | 98 | 77 (70.6) | 31 | 1 (3.2) | 98 | 8 (8.1) | |||||

| Setting | 0.012 | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.010 | 0.26 | |||||||||||

| Urban | 754 (76.4) | 754 | 554 (73.5) | 697 | 190 (27.3) | 754 | 520 (69.0) | 432 | 86 (19.9) | 358 | 39 (10.9) | |||||

| Peri-urban | 192 (19.4) | 192 | 154 (80.2) | 181 | 28 (15.5) | 192 | 140 (72.9) | 121 | 33 (27.3) | 12 | 0 | |||||

| Rural | 41 (4.1) | 41 | 37 (90.2) | 41 | 2 (4.9) | 41 | 28 (6.4) | 31 | 1 (3.2) | 10 | 0 | |||||

| Level of care | <0.0001 | 0.015 | 0.46 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||||||

| Primary | 418 (42.0) | 418 | 289 (69.1) | 377 | 73 (19.4) | 418 | 299 (71.5) | 230 | 76 (33.0) | 162 | 5 (3.1) | |||||

| Secondary | 200 (20.0) | 200 | 154 (77.0) | 189 | 56 (29.6) | 200 | 140 (70) | 105 | 20 (19.0) | 78 | 8 (10.3) | |||||

| Tertiary | 369 (38.0) | 369 | 302 (81.8) | 353 | 91 (25.8) | 369 | 249 (67.5) | 249 | 24 (9.6) | 140 | 26 (18.6) | |||||

| Treating adults and children | 0.64 | <0.0001 | 0.13 | 0.69 | <0.0001 | |||||||||||

| Adults and children | 735 (74.5) | 735 | 552 (75.1) | 667 | 137 (20.6) | 735 | 522 (71.0) | 405 | 85 (21.0) | 133 | 25 (18.8) | |||||

| Adults only | 252 (25.5) | 252 | 193 (76.6) | 252 | 83 (32.9) | 252 | 166 (6–5.86) | 179 | 35 (19.6) | 247 | 14 (5.7) | |||||

| Cumulative number of adults enrolled in HIV care | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.069 | <0.0001 | 0.22 | |||||||||||

| Below 1,000 | 27 (2.9) | 27 | 21 (77.8) | 27 | 5 (18.5) | 27 | 23 (85.2) | 14 | 0 | 13 | 0 | |||||

| 1,001 to 10,000 | 739 (78.3) | 739 | 541 (73.2) | 671 | 172 (25.6) | 739 | 494 (66.9) | 410 | 107 (26.1) | 355 | 39 (11.0) | |||||

| 10,001 to 20,000 | 178 (18.9) | 178 | 141 (79.2) | 178 | 41 (23.0) | 178 | 128 (71.9) | 117 | 13 (11.1) | 12 | 0 | |||||

| New TB cases per year, n | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.016 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | |||||||||||

| Below 100 | 280 (28.4) | 280 | 184 (65.7) | 212 | 54 (25.5) | 280 | 198 (70.7) | 138 | 12 (8.7) | 214 | 30 (14.0) | |||||

| 100 to 1,000 | 471 (47.7) | 471 | 366 (77.7) | 471 | 88 (18.7) | 471 | 310 (65.8) | 331 | 74 (22.4) | 101 | 1 (1.0) | |||||

| >1,000 | 236 (23.9) | 236 | 195 (82.6) | 236 | 78 (33.4) | 236 | 180 (76.3) | 115 | 34 (29.6) | 65 | 8 (12.3) | |||||

The analysis was restricted to patients from sites with access to the diagnostic tools.

Chi square tests were used to calculate P values.

Costs to patients, availability and use

In about half of sites services were free to patients (23 sites, 48.9%). In the other sites (24 sites, 51.1%), the median cost to patients was 2.1 USD (12 sites, IQR 1.5–3.0) for sputum smear microscopy, 25.0 USD (12 sites, IQR 13.7–40.7) for culture, 7.7 USD (20 sites, IQR 5.3–12.0) for chest radiographs, and 50.0 USD (3 sites, IQR 29.6–129.8) for Xpert MTB/RIF. The availability of TB diagnostics was similar in sites providing services for free compared to sites charging patients. But expensive diagnostics (more than 20.0 USD per test) were more frequently used in sites where patients did not have to pay for it. Mycobacterial culture was used in 26.8% of patients from the 20 sites offering free cultures versus 20.8% in the other sites (p = 0.033, Table 4). The same was true for Xpert MTB/RIF (26.2% versus 15.2%, p = 0.001). In contrast, there was no evidence that diagnostics such as sputum microscopy or chest X-ray were more frequently used in sites providing services free of charge (Table 4).

Table 4. Availability and use of tuberculosis (TB) diagnostics in HIV-infected individuals, comparing sites with a cost model of free services to the patients and all other sites with full payment, cost sharing or any other cost model.

| Diagnostic | Access to diagnostics in sites, n (%) | Use of diagnostics in patients with access to the diagnostics, n (%) | ||||||

| Total | Sites with free service | All other sites | P value | Total | Sites with free service | All other sites | P value | |

| (n = 987) | (n = 545) | (n = 442) | ||||||

| Sputum microscopy | 40 | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 0.99 | 987 (100) | 415 (76.1) | 330 (74.6) | 0.59 |

| Culture | 37 | 17 (85.0) | 20 (100) | 0.072 | 919 (93.1) | 128 (26.8) | 92 (20.8) | 0.033 |

| Xpert MTB/RIF | 20 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | 0.21 | 584 (59.1) | 74 (26.2) | 46 (15.2) | 0.001 |

| Chest X-Ray | 40 | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 0.99 | 987 (100) | 368 (67.5) | 320 (72.4) | 0.10 |

| Tuberculin skin test | 23 | 9 (45.0) | 14 (70.0) | 0.11 | 380 (38.5) | 9 (5.7) | 30 (13.8) | 0.012 |

Analysis was restricted to sites which contributed patient data and to patients from sites with access to the diagnostics.

Chi square tests were used to calculate P values.

Screening practices before ART initiation

Forty-four (93.6%) sites reported following national guidelines to screen suspected TB cases. Screening practices for active disease included symptom screening (46 sites, 97.9%), chest X-ray (38 sites, 80.9%), sputum smear microscopy (37 sites, 78.7%), culture (16 sites, 34.0%), TST (11 sites, 23.4%) and Xpert MTB/RIF (5 sites, 10.6%, Table S5). To examine the approach of physicians and clinical officers to screen for TB, we confronted them with the hypothetical scenario of an adult newly diagnosed with HIV. At the 46 sites reporting symptom screening as part of their screening practices, 43 (93.5%) physicians reported choosing symptom to screen for TB. In contrast, less than a quarter of clinicians mentioned using sputum smear microscopy and Xpert MTB/RIF despite the fact that these diagnostics were part of the screening practices at their site.

Discussion

We surveyed 47 ART sites in a global network of HIV adult treatment programs. We found that the use of mycobacterial culture for TB diagnosis was low despite its availability at most sites, while Xpert MTB/RIF was both infrequently available and used. Programs providing services free of charge were associated with higher levels of use of the available diagnostic tools. Our study builds on a smaller survey of the ART in Lower Income Countries (ART-LINC) collaboration in 2008, which showed that the availability of TB diagnostics varied widely across ART programs [18]. The present study covered many additional sites within the larger IeDEA network across Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and Central and South America and offers a global view on ART programs in the low and middle-income countries heavily affected by the generalized HIV and TB epidemics. In this study, we also collected and analyzed information on individual patients and the clinical decision making by treating physicians and clinical officers. This approach allowed us to study the availability, use, and practice of TB diagnostics in parallel.

We found that TB diagnostics were not systematically used even when available. This was illustrated by sputum microscopy and mycobacterial culture, which were not necessarily used for the diagnosis of pulmonary TB even in sites with access to these diagnostics. The discrepancy between availability and use underlines that programmatic issues are essential to the control of TB in the HIV-positive population and need to be considered when new TB diagnostic and screening tools become available in ART programs. Lin and colleagues recently showed that not only new tools are needed to improve TB control, but that the overall quality of patient care and the reduction of patient loss before diagnosis need to be considered as part of an overall implementation concept [25]. The low use of available tools could also be a reflection of some sites performing culture or sputum microscopy only in selected cases, such as treatment failure or relapse, depending on their guidelines. It could also reflect breakdowns in the supply chain for reagents, lack of local expertise on how to use these tools, adherence to national guidelines, or the cost of the test.

The availability of diagnostic tools was similar in programs providing tests free of charge and programs charging patients, but some diagnostics were more frequently used where no costs to patients were incurred. This was particularly true for the automated molecular diagnostic assay Xpert MTB/RIF. It appears that not only the distance to the diagnostic facility matters [26], but also the costs of these diagnostics to the patients. Even if the price of TB diagnostics such as Xpert MTB/RIF has been reduced [27], the costs to the patients may still be prohibitive in relation to their budget. Patients may face difficult choices when balancing the costs of diagnostics with other demands on the family budget. Having free TB diagnostics appears to be important for the successful implementation of TB control in the HIV-infected population.

Our study has several limitations. The results were based on a survey mainly reflecting the situation during the study period as reported by the site representatives. It is therefore difficult to distinguish between intermittent or consistent availability and use. However, we substantiated our findings by collecting data from patient seen during the study period, and by assessing scenarios to capture the clinical decision making of treating physicians and clinical officers.

The ART programs participating in the IeDEA network may not be representative of all ART programs in a country or region. IeDEA sites tend to be located in urban settings, collect data using electronic medical record systems and many of them participate in additional research projects outside the IeDEA collaboration. Of note, a recent survey of HIV care centers in sub-Saharan Africa within the International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs (ICAP)-Columbia University program showed a lower availability of TB diagnostics such as sputum smear microscopy and culture than in our study [28]. This might be explained by the nature of the ICAP program, which consisted of a larger proportion of smaller sites in rural settings, compared to the IeDEA collaboration, which included larger sites in urban settings [21]. Unfortunately, there are only few studies examining availability and use of TB diagnostics in ART programs in low and middle-income countries, which limits the potential for comparisons with other settings. Another limitation is that the analysis of individual patient data was based on those having been diagnosed with TB, rather than those suspected of having TB, although the latter case was addressed in a hypothetical case scenario. Finally, we cannot exclude that the answers provided by the clinicians in the scenarios strictly represented the current practice in their ART program.

In conclusion, we found that access to and use of TB diagnostics is still limited in ART programs and that tests are not systematically used, even when available. Improved diagnostic capacities are necessary for better patient care, to increase TB case retention, reduce delays before treatment initiation, and thereby reducing the risk of onward transmission. Our study suggests that the availability of diagnostics alone does not automatically lead to their use at the patient level, particularly if not free of charge to patients.

Our report underlines the challenges of implementing TB diagnostics in the field. Therefore, when implementing TB diagnostics, our study suggests that it is crucial to consider the affordability of diagnostic tests, the supply chain of reagents, training of laboratory staff, short distances to diagnostic facilities, and prompt access to TB care for diagnosed patients [25], [29]. Further studies need to focus on the barriers preventing access to TB diagnostics and their adequate use. This may have implications for the situation in ART programs as well as TB care centers outside of ART programs. In the meantime, we will continue to monitor availability and use of diagnostics in ART programs in resource limited settings.

Supporting Information

List of all ART programs participating in the survey and which completed at least Section A (n = 58), including programs treating adults, children, or both. Sites marked with a star are programs treating children only and were therefore excluded from the present analysis.

(DOC)

Eight hypothetical cases typical for different clinical situations in the context of HIV and tuberculosis management.

(DOC)

Characteristics of adult tuberculosis (TB) patients seen during the study period from antiretroviral (ART) programs in lower income countries, overall and stratified by IeDEA regions.

(DOC)

Availability of TB diagnostics in 47 adult ART programs in lower income countries, by IeDEA regions.

(DOC)

Diagnostic tools as part of the screening practices to diagnose active TB in HIV-infected individuals before starting ART in 47 adult ART programs in lower income countries, overall and stratified by IeDEA regions.

(DOC)

IeDEA tuberculosis working group and participating IeDEA sites and investigators.

(DOC)

Ethics statement including a full list of Ethics Committees and/or Institutional Review Boards.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank all sites who participated in this survey and the patients whose data were used in this study. We are indebted to the advisory panel that helped to develop the survey project and the IeDEA Tuberculosis Working group for following up on the project's progress. We also would like to thank all regional data centers who contributed to the coordination of the study, as well as the recording and entry of data.

Funding Statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number Southern Africa: U01AI069924, Asia: U01AI069907, Central Africa: U01A096299, East Africa: U01AI069911, Caribbean, Central and South America: U01AI069923 and West Africa: U01AI069919. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R (2008) Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 22: 1897–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brinkhof MW, Egger M, Boulle A, May M, Hosseinipour M, et al. (2007) Tuberculosis after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in low-income and high-income countries. Clin Infect Dis 45: 1518–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lawn SD, Wilkinson RJ, Lipman MC, Wood R (2008) Immune reconstitution and "unmasking" of tuberculosis during antiretroviral therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177: 680–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koenig SP, Riviere C, Leger P, Jospeh P, Severe P, et al. (2009) High mortality among patients with AIDS who received a diagnosis of tuberculosis in the first 3 months of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 48: 829–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies MA, Meintjes G (2009) Assessing the contribution of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome to mortality in developing country antiretroviral therapy programs. Clin Infect Dis 49: 973–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moh R, Danel C, Messou E, Ouassa T, Gabillard D, et al. (2007) Incidence and determinants of mortality and morbidity following early antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV-infected adults in West Africa. AIDS 21: 2483–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meintjes G, Lawn SD, Scano F, Maartens G, French MA, et al. (2008) Tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: case definitions for use in resource-limited settings. Lancet Infect Dis 8: 516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, et al. (2010) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 10: 251–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Badri M, Wilson D, Wood R (2002) Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet 359: 2059–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edmonds A, Lusiama J, Napravnik S, Kitetele F, Van RA et al.. (2009) Anti-retroviral therapy reduces incident tuberculosis in HIV-infected children. Int J Epidemiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Suthar AB, Lawn SD, del Amo J, Getahun H, Dye C, et al. (2012) Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of tuberculosis in adults with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 9: e1001270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aït-Khaled N, Alarcon E, Bissell K, Boillot F, Caminero JA, et al. (2009) Isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV: public health challenges and implementation issues. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 13: 927–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corbett EL, Marston B, Churchyard GJ, De Cock KM (2006) Tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities, challenges, and change in the era of antiretroviral treatment. Lancet 367: 926–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lönnroth K, Raviglione M (2008) Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: prospect for control. Sem Respir Crit Care Med 29: 481–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, et al. (2010) Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine 362: 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, Borand L, Rekacewicz C, et al. (2011) Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-Infected adults with tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine 365: 1471–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Havlir DV, Kendall MA, Ive P, Kumwenda J, Swindells S, et al. (2011) Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine 365: 1482–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fenner L, Forster M, Boulle A, Phiri S, Braitstein P, et al. (2011) Tuberculosis in HIV programmes in lower-income countries: practices and risk factors. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 620–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boehme CC, Nicol MP, Nabeta P, Michael JS, Gotuzzo E, et al. (2011) Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: a multicentre implementation study. Lancet 377: 1495–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicol MP, Workman L, Isaacs W, Munro J, Black F, et al. (2011) Accuracy of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children admitted to hospital in Cape Town, South Africa: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 11: 819–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, Lyamuya RE, Mukumbi H, et al. (2012) Cohort Profile: the international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol 41: 1256–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gange SJ, Kitahata MM, Saag MS, Bangsberg DR, Bosch RJ, et al. (2007) Cohort profile: the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). Int J Epidemiol 36: 294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McGowan CC, Cahn P, Gotuzzo E, Padgett D, Pape JW, et al. (2007) Cohort Profile: Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV research (CCASAnet) collaboration within the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) programme. Int J Epidemiol 36: 969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, et al. (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin HH, Dowdy D, Dye C, Murray M, Cohen T (2012) The impact of new tuberculosis diagnostics on transmission: why context matters. Bull World Health Organ 90: 739–747A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lawn SD, Kerkhoff AD, Wood R (2012) Location of Xpert(R) MTB/RIF in centralised laboratories in South Africa undermines potential impact. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 16: 701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization (2011) Rapid implementation of the Xpert MTB/RIF diagnostic test. Technical and operational 'How to' practical considerations. World Health Organization Document WHO/HTM/TB/2011 2: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saito S, Howard AA, Reid MJ, Elul B, Scardigli A, et al. (2012) TB diagnostic capacity in sub-Saharan African HIV care settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 61: 216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zumla A, Abubakar I, Raviglione M, Hoelscher M, Ditiu L, et al. (2012) Drug-resistant tuberculosis -- current dilemmas, unanswered questions, challenges, and priority needs. Journal of Infectious Diseases 205: S228–S240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of all ART programs participating in the survey and which completed at least Section A (n = 58), including programs treating adults, children, or both. Sites marked with a star are programs treating children only and were therefore excluded from the present analysis.

(DOC)

Eight hypothetical cases typical for different clinical situations in the context of HIV and tuberculosis management.

(DOC)

Characteristics of adult tuberculosis (TB) patients seen during the study period from antiretroviral (ART) programs in lower income countries, overall and stratified by IeDEA regions.

(DOC)

Availability of TB diagnostics in 47 adult ART programs in lower income countries, by IeDEA regions.

(DOC)

Diagnostic tools as part of the screening practices to diagnose active TB in HIV-infected individuals before starting ART in 47 adult ART programs in lower income countries, overall and stratified by IeDEA regions.

(DOC)

IeDEA tuberculosis working group and participating IeDEA sites and investigators.

(DOC)

Ethics statement including a full list of Ethics Committees and/or Institutional Review Boards.

(DOC)