Background: LOXL2 induces metastasis/invasion of breast cancer cells.

Results: MCF-7 cells expressing nuclear associated LOXL2 have an invasive EMT phenotype.

Conclusion: Nuclear associated catalytically competent LOXL2 contributes to stabilization of Snail1 transcription factor.

Significance: This is the first study to directly compare the potencies of nuclear associated and secreted LOXL2s in breast cancer metastasis/invasion in vitro.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Cell Invasion, Epithelial-to-mesenchymal Transition, Lysyl Oxidase, Post-translational Modification, Site-directed Mutagenesis, Lysyl Oxidase-Like 2

Abstract

LOXL2 is a copper- and lysine tyrosylquinone-dependent amine oxidase that has been proposed to function both extracellularly and intracellularly to activate oncogenic signaling pathways leading to EMT and invasion of breast cancer cells. In this study, we selected MCF-7 cells that stably express forms of recombinant LOXL2 differing in their subcellular localizations and catalytic competencies. This enabled us to dissect the molecular functions of intracellular and extracellular LOXL2s and examine their contributions to breast cancer metastasis/invasion. We discovered that secreted LOXL2 (∼100-kDa) is N-glycosylated at Asn-455 and Asn-644, whereas intracellular LOXL2 (∼75-kDa) is nonglycosylated and N-terminally processed, and is primarily associated with the nucleus. Both forms of LOXL2 can oxidize lysine in solution. However, we found that expression of intracellular LOXL2 is more strongly associated with EMT and invasiveness than secreted LOXL2 in vitro. The results indicate that nuclear associated LOXL2 contributes to the stabilization of Snail1 transcription factor at the protein level to induce EMT and promote invasion in vitro, through repression of E-cadherin, occludin, and estrogen receptor-α, and up-regulation of vimentin, fibronectin, and MT1-MMP.

Introduction

Lysyl oxidase (LOX)4 and lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2) are copper-dependent amine oxidases that contain lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ), a cofactor that is post-translationally derived from conserved Lys-653 and Tyr-689 (numbered according to LOXL2) residues by Cu2+ and molecular oxygen (1–3). LOX and LOXL2 share a highly conserved C-terminal amine oxidase domain, but LOXL2 differs from LOX at its N terminus, bearing four scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domains. LOX and LOXL2 are highly up-regulated in metastatic/invasive breast cancer cells and tissues, and their expression promotes invasion of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo (4, 5). LOX-induced ECM stiffening has been shown to alter cellular mechanotransduction and activate the focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/Src signaling pathway, thereby promoting cell proliferation, metastatic dissemination, and invasion of breast cancer cells (6–9). Analogously, ECM stiffening caused by secreted LOXL2 is proposed to be responsible for promoting the invasion of breast cancer cells through up-regulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) (10). Alternatively, secreted LOX and LOXL2 are hypothesized to promote tumor metastasis and invasion of breast and gastric cancer by activating the focal adhesion kinase/Src pathway via hydrogen peroxide, a byproduct formed during the oxidation of ECM substrates by these proteins (11, 12). Recently, an antibody developed to specifically target the fourth SRCR domain of LOXL2 was shown to reduce the invasive potential of MDA-MB-435 cells in xenograft models, supporting the proposed ECM function of LOXL2 (13).

Intracellular functions of LOXL2 have also been postulated because a perinuclear expression pattern of LOXL2 has been reported for some basal-like breast and larynx squamous carcinomas (14–16). One proposal is that LOXL2 induces EMT by stabilizing Snail1 transcription factor, a suppressor of CDH1 (E-cadherin) (17). In this mechanism, LOXL2 oxidizes Lys-98 and/or Lys-137 of Snail1 to induce an undefined conformational change that protects Snail1 from glycogen synthase kinase 3 β (GSK3β)-catalyzed phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitinylation and proteasomal degradation. Alternatively, LOXL2 is hypothesized to down-regulate CDH1 through demethylation of trimethylated Lys-4 of histone H3 (H3K4(me3)) (18). For this second mechanism, two unprecedented roles of LOXL2 have been proposed: catalyzing the demethylation of H3K4(me3) to form an alcohol, and the subsequent oxidation of the alcohol to an aldehyde. Finally, it has also been suggested that LOXL2 regulates cell polarity in basal-like breast cancer cells by transcriptionally down-regulating tight junction proteins (claudin-1 and Lgl2) independently of E-cadherin (15).

We wish to dissect and understand the molecular functions of LOXL2 in relation to breast cancer metastasis/invasion so that ultimately therapies targeting this protein can be developed. During the course of our study to define the extent and functions of the post-translational modifications (PTMs) of LOXL2, we selected MCF-7 cells stably expressing recombinant LOXL2s differing in their subcellular localizations and catalytic competencies. This study describes our examination of these different LOXL2s, focusing on their respective potencies to induce EMT and promote invasion in vitro.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. (Walkersville, MD). Heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and tunicamycin were from Sigma-Aldrich. The cDNA containing the complete open reading frame of LOXL2 (GenBank accession number: NM_002318.2) was from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD). pEXPR-IBA42 vector and MagStrep type2HC beads were from IBA (Göttingen, Germany). pcDNA3.1/Hygro(−), hygromycin B, and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen. SuperFect transfection reagent was from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) and endoglycosidase H (Endo H) were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, Halt EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture, and Halt phosphatase inhibitor mixture were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cycloheximide (CHX) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Expression Vector Construction and Site-directed Mutagenesis

The Strep-tag II coding sequence was engineered at the 3′ end of the gene of interest by first subcloning the gene into a vector containing Strep-tag II (i.e. pEXPR-IBA42), and then LOXL2-StrepII DNA was lifted out by PCR and cloned into pcDNA3.1/Hygro(−) expression vector. The asparagine residues at 288, 455, and 644 of LOXL2 were mutated to glutamine by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) to produce N288Q, N455Q, and N644Q mutants. The primer pair used to generate the N288Q mutant was: forward (5′-GGACCCCATGAAGCAAGTCACCTGCGAG-3′), reverse (5′-CTCGCAGGTGACTTGCTTCATGGGGTCC-3′). The sets of primers for generating N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 are described elsewhere (19). The lysine residue at 653 was mutated to either arginine (K653R) or serine (K653S) using the following primer pairs: K653R forward (5′-CAGAGGGCCACAGGGCCAGCTTCTG-3′), K653R reverse (5′-CAGAAGCTGGCCCTGTGGCCCTCTG-3′); K653S forward (5′-CAGAGGGCCACAGTGCCAGCTTCTGCT-3′), K653S reverse (5′-AGCAGAAGCTGGCACTGTGGCCCTCTG-3′). Sequences were then validated by DNA sequencing (DNA Sequencing Facility at the University of California, Berkeley).

Stable Transfection and Expression of LOXL2 in MCF-7 Cells

MCF-7 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Transfection with the pcDNA construct was performed at 70% confluency. Stable cell lines were selected from single cells in the presence of 150 μg/ml hygromycin. After 1 month, stable MCF-7 cell lines were expanded and adapted to serum-free medium (SFM) for protein isolation.

Bright Field Microscopy

Cells were seeded in 25-cm2 T-flasks and cultured to ∼50% confluency. Bright field images of live cells were captured using an IX81 inverted research microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) fitted with a 20× objective and a humidified enclosure maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Images were acquired using Slidebook version 5.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). All raw images were processed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunoblot Analysis

The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: mouse StrepMAB-Classic (IBA); rabbit anti-LOXL2 and mouse anti-vimentin (Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit anti-Snail1, rabbit anti-claudin-1, rabbit anti-GSK3β, rabbit anti-estrogen receptor α, rabbit anti-MMP-2, and rabbit anti-MMP-9 (Cell Signaling Technology); rabbit anti-β-actin, rabbit anti-fibronectin, rabbit anti-lamin B1, mouse anti-E-cadherin, rabbit anti-occludin, mouse anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and rabbit anti-Snail1 (Abcam); and rabbit anti-MT1-MMP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The secondary antibodies used were: HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG and HRP-linked goat anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology).

Subcellular Fractionation

The soluble cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of MDA-MB-231 cells and various stable MCF-7 cells were isolated using the subcellular protein fractionation kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce).

Tunicamycin, PNGase F, and Endo H Treatments

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured to preconfluence and then adapted to SFM with 10 μg/ml tunicamycin for 12 h before harvest. For PNGase F and Endo H treatment, protein samples were concentrated and then denatured and enzymatically deglycosylated at 37 °C for 3 h.

LOX Activity Assay

N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 from soluble cell lysates and WT LOXL2 from conditioned SFM were isolated using MagStrep type2HC beads, according to the manufacturer's protocol (IBA). The amine oxidase activity of the isolated proteins was determined by the standard Amplex Red assay at pH 8.0 and 37 °C, following the described method (20) with some modification. Briefly, 1 μg of isolated proteins was preincubated with reaction mixture consisting of 50 mm HEPBS (pH 8.0), 50 μm Amplex Red, and 0.1 unit/ml horseradish peroxidase (total volume of 98 μl) at 37 °C for 2 min. 2 μl of l-lysine (final concentration of 50 μm) was added to this mixture to initiate the reaction. The absorbance increase at 560 nm, corresponding to the formation of the oxidized Amplex Red (resorufin), was measured as the change in milliabsorbance units per minute by a Shimadzu UV-2550 UV-visible spectrophotometer with a Peltier temperature controller set to 37 °C. Initial rates of substrate oxidation were collected as triplicates from the linear slopes of the absorbance change at 560 nm after the substrate was added. The unit of rate was converted from milliabsorbance units per minute to pmol of H2O2 formed per minute per μg of LOXL2 (pmol of H2O2/min/μg). The ϵ value for resorufin at 560 nm was determined to be 54,400 ± 600 m−1cm−1.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (3 × 105) were seeded in P35 dishes and grown to 70% confluency. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA and random hexamers using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs). PCR amplification of cDNA was carried out using the following primer pairs: E-cadherin (5′-CAGCACGTACACAGCCCTAA-3′, 5′-ACCTGAGGCTTTGGATTCCT-3′); occludin (5′-GATGACTTCAGGCAGCCTCG-3′, 5′-CTATGTTTTCTGTCTATCATAGTC-3′); estrogen receptor α (5′-TGGGCTTACTGACCAACCTG-3′, 5′-CCTGATCATGGAGGGTCAAA-3′); vimentin (5′-CCGACAGGATGTTGACAATG-3′, 5′-TCAGAGAGGTCGGCAAACTT-3′); fibronectin (5′-GGTTTCCCATTATGCCATTG-3′, 5′-TTCCAAGACATGTGCAGCTC-3′); Snail1 (5′-GAAAGGCCTTCAACTGCAAA-3′, 5′-TGACATCTGAGTGGGTCTGG-3′); glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (5′-AACATCATCCCTGCTTCCAC-3′, 5′-GACCACCTGGTCCTCAGTGT-3′). The following two-step PCR conditions were used: 95 °C for 30 s, 95 °C for 30 s, and 55 °C for 30 s for a total of 30 cycles. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel.

Matrigel in Vitro Invasion Assay

An in vitro invasion assay was conducted using BD BioCoat Matrigel invasion chambers (BD Biosciences). MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells in conditioned SFM were added (2.5 × 104/well) to the upper chambers and allowed to invade through the Matrigel or migrate through the control insert. Growth medium in the lower chamber contained 5% FBS as a chemoattractant. The upper chambers were then rinsed with SFM and wiped with cotton swabs to remove noninvading cells. Cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed and stained with Diff-Quik staining kit (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA). The cells were counted at three random views per membrane under the microscope. Assays were run in triplicate.

Snail1 Stability during CHX Treatment

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (0.5 × 106) were adapted to SFM for 2 days in P60 dishes and then incubated with 10 μg/ml CHX for the time intervals of 0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h. The expression level of Snail1 in cell lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-Snail1 antibody.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Student's t test and considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selection of MCF-7 Cells Stably Expressing Catalytically Competent Intracellular or Extracellular LOXL2

This study began as an investigation into the functions of the PTMs of LOXL2. First, we selected MCF-7 cells stably expressing full-length wild-type LOXL2 (WT LOXL2) fused to a C-terminal Strep-tag II (i.e. an affinity tag with the amino acid sequence WSHPQFEK) and found that WT LOXL2 was mostly secreted as an ∼100-kDa protein, as reported previously (Fig. 1A) (21). The endogenous LOXL2 secreted from MDA-MB-231 cells was also ∼100 kDa, which is significantly larger than the predicted molecular mass of ∼84 kDa for residues 26–774 of LOXL2 (i.e. LOXL2 without the predicted signal peptide). PNGase F treatment of the culture media of MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-7 cells stably expressing WT LOXL2 noticeably reduced the mass of both LOXL2s, indicating that the secreted LOXL2s were N-glycosylated (Fig. 1A). Using truncated LOXL2s produced in Drosophila Schneider 2 (S2) cells, we recently demonstrated that secreted LOXL2 is N-glycosylated at least at Asn-455 and Asn-644 and that the N-linked glycans at these sites are independently important for proper protein folding and secretion from S2 cells (19, 22). In addition to Asn-455 and Asn-644, NetNGlyc 1.0 server predicts that Asn-288 is also an N-glycosylation site (i.e. Asn-X-(Ser/Thr)) in LOXL2, whereas NetOGlyc 3.1 server predicts no O-linked glycosylation sites in LOXL2.

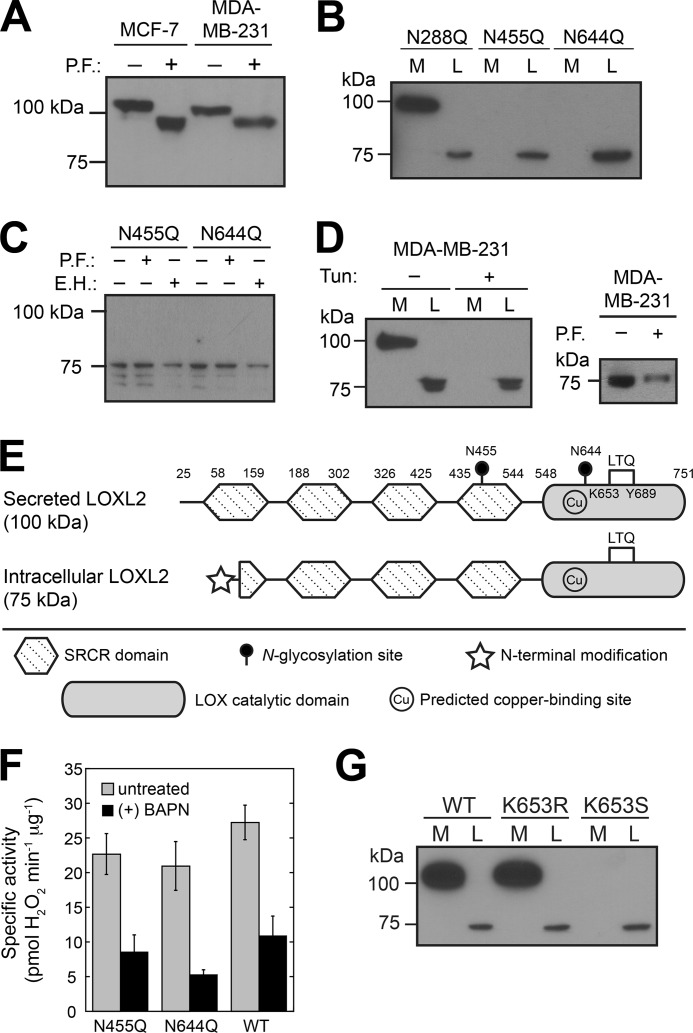

FIGURE 1.

Secreted LOXL2 is N-glycosylated at Asn-455 and Asn-644, whereas cytosolic LOXL2 is nonglycosylated, N-terminally processed, and N-terminally modified. A, PNGase F (P.F.) treatment reduces the masses of recombinant WT LOXL2 and endogenous LOXL2 secreted from stable MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. B, N-glycosylation at Asn-455 and Asn-644, but not Asn-288, is essential for secretion into the growth medium (M). A 75-kDa form of LOXL2 is detected in the lysates (L) of all cell lines. C, PNGase F and Endo H (E.H.) treatment do not alter the masses of N455Q and N644Q LOXL2. D, left panel, tunicamycin (Tun.) treatment blocks secretion of endogenous LOXL2 from MDA-MB-231 cells. A non-N-glycosylated intracellular LOXL2 is expressed with or without tunicamycin treatment. Right panel: PNGase-F treatment of MDA-MB-231 cell lysates does not reduce the mass of intracellular LOXL2. E, schematic diagrams of secreted and intracellular LOXL2. The precursor residues for the LTQ cofactor are Lys-653 and Tyr-689. The predicted secretion signal encompasses residues 1–25 (not shown). The predicted copper-binding site is His-626-XX-His-628-XX-His-630. F, N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 (isolated from stable MCF-7 cell lysates) and WT LOXL2 (isolated from the growth medium of stable MCF-7 cells) have similar specific activity toward lysine in the standard Amplex Red assay at 37 °C, pH 8.0. Error bars indicate means ± S.E. G, the positive charge at residue 653 (but not the LTQ cofactor) is essential for folding and secretion of LOXL2 from stable MCF-7 cells.

To determine whether Asn-288 is N-glycosylated in WT LOXL2 and to confirm that N-glycosylation is important for the secretion of LOXL2 from breast cancer cells, we selected stable MCF-7 cells expressing N288Q, N455Q, and N644Q LOXL2s. We detected N288Q LOXL2 mostly in the culture medium as an ∼100-kDa protein, indicating that Asn-288 is not N-glycosylated (Fig. 1B). In contrast, neither N455Q LOXL2 nor N644Q LOXL2 were secreted from stable MCF-7 cells, but were instead found in the soluble cell lysate as ∼75-kDa proteins. These 75-kDa forms of N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 seemed not to be glycosylated at all as neither PNGase F treatment nor endoglycosidase H treatment affected the size of these proteins (Fig. 1C). These results confirm that the N-linked glycans at Asn-455 and Asn-644 are independently essential for secretion from breast cancer cells as disruption of N-glycosylation at either site results in the loss of the N-linked glycan at the other site and total inhibition of secretion, a phenomenon for which there is some precedent (23, 24). Interestingly, the N455Q and N644Q LOXL2s produced in MCF-7 cells were soluble, in contrast to the corresponding truncated forms of recombinant LOXL2 expressed in S2 cells, which were detected in minute quantities only in the insoluble S2 cell lysate, implicating rapid endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of nonglycosylated LOXL2 (19). The stark difference suggests that in MCF-7 cells, the N-linked glycans are essential neither for the folding nor for the stability of LOXL2.

In a complementary experiment, tunicamycin, an inhibitor of GlcNAc C-1-phosphotransferase (25), was added to the growth medium of MDA-MB-231 cells, whereupon no secretion of endogenous LOXL2 was observed. Instead, ∼75-kDa LOXL2 was found in the soluble cell lysate (Fig. 1D, left panel). Similar to N455Q and N644Q LOXL2s, the size of ∼75-kDa LOXL2 in MDA-MB-231 cells was not reduced after PNGase F treatment (Fig. 1D, right panel). Altogether, these data support our hypothesis that the intracellular ∼75-kDa LOXL2 is not N-glycosylated. Intriguingly, we also detected the ∼75-kDa LOXL2 in the soluble cell lysate of MDA-MB-231 cells without tunicamycin treatment (Fig. 1D, left panel), as well as in the lysates of MCF-7 cells stably expressing either N288Q LOXL2 or WT LOXL2 (Fig. 1, B and G). These MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells are all capable of producing ∼100-kDa N-glycosylated LOXL2; thus, it is probable that LOXL2 overexpression in these cells overwhelms or saturates the glycosylation pathway, allowing some LOXL2 to escape glycosylation and consequently avoid secretion. In addition, the mass of the full-length nonglycosylated LOXL2 without the predicted signal peptide (i.e. without residues 1–25) is ∼84 kDa, suggesting that an ∼9-kDa fragment of the first SRCR domain was processed to produce the 75-kDa forms (Fig. 1E). We subjected N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 to N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation (Stanford PAN Facility); however, the N termini were blocked. This is somewhat expected as at least 80–90% of eukaryotic cytosolic proteins are reported to be N-terminally blocked (26). Efforts to identify the protease responsible for the formation of ∼75-kDa LOXL2 are underway.

We examined the catalytic competencies of N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 purified from stable MCF-7 cell lysates, as well as WT LOXL2 isolated from stable MCF-7 cell medium, and found that the nonglycosylated LOXL2s were as active as the N-glycosylated WT LOXL2 in the oxidation of l-lysine, an in vitro LOX substrate (Fig. 1F). Moreover, all three forms of LOXL2 are inhibited roughly equally by β-aminopropionitrile, which is commonly used to inhibit LOX and LOXL2 in solution (27, 28). These results suggest that the N-terminal modification of ∼75-kDa LOXL2 and the absence of N-linked glycans at Asn-455 and Asn-644 do not significantly impact the catalytic properties of LOXL2 in solution.

Selection of MCF-7 Cells Stably Expressing Catalytically Incompetent Intracellular or Extracellular LOXL2

We previously confirmed by mass spectrometry that Lys-653 and Tyr-689 are the precursor residues for the LTQ cofactor in LOXL2 (19). Biogenesis of the LTQ cofactor is proposed to be autocatalytic, requiring only Cu2+ and molecular oxygen (3, 29). Presumably, Cu2+ incorporation and LTQ biogenesis take place in the endoplasmic reticulum, which is a more oxidative environment than the cytosol (30). Model studies indicate that biogenesis occurs after the active site is prearranged (31, 32).

To examine whether LTQ cofactor formation is a prerequisite for LOXL2 maturation, we selected MCF-7 cells stably expressing K653R or K653S LOXL2, neither of which is capable of forming the LTQ cofactor. K653R LOXL2 was secreted into the medium and detected as an ∼100-kDa protein, identical in size to N-glycosylated full-length WT LOXL2 (Fig. 1G). In contrast, K653S LOXL2 was detected exclusively as ∼75-kDa protein in the soluble lysate, identical to N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 (Fig. 1, B and G). These data demonstrate that when the positive charge of the side chain at residue 653 is preserved, the LOXL2 maturation pathway is not sufficiently sensitive to distinguish LOXL2 containing the precursor residues of the LTQ cofactor from LOXL2 with properly cross-linked LTQ. This may account for the nonstoichiometric amount of LTQ cofactor detected in native LOX (33). However, removal of the charge (i.e. K653S) seems to have completely inhibited N-glycosylation. Because the N-glycosylation site at Asn-644 is within eight amino acid residues of Lys-653, it is possible that elimination of the positive charge in the active site induced some conformational change that impeded N-glycosylation and directed LOXL2 down the same path as N455Q and N644Q LOXL2, i.e. toward processing to an ∼75-kDa form that was retained in the cytosol. In any case, we were able to select MCF-7 cells expressing catalytically incompetent LOXL2 in either the medium or the cytosol (i.e. K653R or K653S LOXL2, respectively).

MCF-7 Cells Stably Expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2 Exhibit Mesenchymal Morphology

Upon selecting MCF-7 cells stably expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2, we were surprised to notice that the cells no longer displayed the cellular morphology characteristic of parental MCF-7 cells (i.e. epithelial, cobblestone-like), and instead had assumed morphology strikingly similar to that of MDA-MB-231 cells (i.e. mesenchymal, spindle-shaped) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, we did not observe any morphological changes for MCF-7 cells stably expressing K653R or K653S LOXL2 (Fig. 2A). MCF-7 cells stably expressing WT or N288Q LOXL2 mostly exhibited epithelial morphology, but minor populations of cells exhibited a mesenchymal appearance, consistent with a previous observation (21).

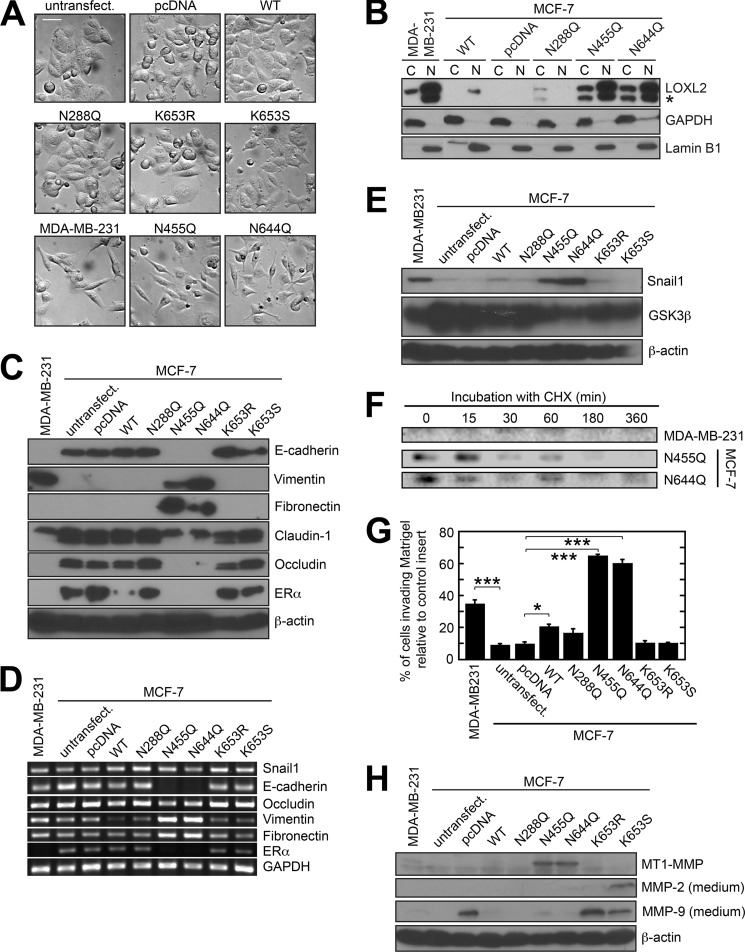

FIGURE 2.

Phenotype comparison of MDA-MB-231 cells, untransfected MCF-7 cells, empty vector-transfected MCF-7 cells, and MCF-7 cells stably expressing various recombinant forms of LOXL2. A, MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2 exhibit spindle-shaped (i.e. mesenchymal) morphology, similar to MDA-MB-231 cells. In contrast, MCF-7 cells stably expressing WT, K653R, K653S, or N288Q LOXL2 exhibit almost exclusively epithelial morphology. All images are the same magnification. Bar: 50 μm. B, immunoblot analysis of the subcellular distribution of endogenous and recombinant LOXL2 in MDA-MB-231 cells and stable MCF-7 cells expressing various forms of recombinant LOXL2, respectively. Lanes were rearranged for clarity of presentation. GAPDH and lamin B1 were used as loading controls for the cytosolic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions, respectively. * denotes a nonspecific protein. C, immunoblot analysis of the expression of several epithelial and mesenchymal markers in MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-7 cells stably expressing various recombinant LOXL2s. β-actin was used as a loading control. D, qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of several epithelial and mesenchymal markers in MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-7 cells stably expressing various recombinant LOXL2s. GAPDH was used as a loading control. E, immunoblot analysis of the expression of Snail1 and GSK3β in MDA-MB-231 cells and various stable MCF-7 cells. β-Actin was used as a loading control. F, immunoblot analysis showing the stability of Snail1 protein in the lysates of CHX-treated MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2. G, a Matrigel in vitro invasion assay was used to determine the invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 cells and various stable MCF-7 cells. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.0001. Error bars indicate means ± S.E. H, immunoblot analysis of the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (in the crude SFM) and MT1-MMP (in the cell lysate) of MDA-MB-231 cells and stable MCF-7 cells. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 Are Nuclear Associated

To explore the mechanism by which the morphological changes of MCF-7 cells stably expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 were induced, we first determined the subcellular localization of LOXL2 in MDA-MB-231 cells and stable MCF-7 cells. To this end, we separated the nuclear and cytosolic fractions of the cell lysates before subjecting them to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). The results indicate that the partitioning of intracellular LOXL2 favors the nuclear fraction in MDA-MB-231 cells, as well as in MCF-7 cells expressing WT, N455Q, and N644Q LOXL2. Not surprisingly, both the nuclear and the total intracellular dosage of LOXL2 in MCF-7 cells expressing WT LOXL2 (which can be secreted) were dramatically lower than in cells expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2 (which cannot be secreted). Thus, our data suggest the likelihood that catalytically competent, nuclear associated LOXL2 plays a dose-dependent role in the phenotypic transformation of MCF-7 cells and may also contribute to the mesenchymal phenotype of MDA-MB-231 cells.

Cells Expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 Exhibit an EMT Phenotype

The morphological transformation of MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2 implicated that these cells had undergone EMT; therefore, we decided to conduct immunoblot analysis to examine the expression levels of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in all the cells (Fig. 2C). We used MDA-MB-231 cells as a positive control for the mesenchymal phenotype, whereas untransfected and empty vector-transfected MCF-7 cells served as positive controls for the epithelial phenotype. In MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-7 cells stably expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2, we did not detect any expression of the classical epithelial marker, E-cadherin. Instead, we detected elevated expression of two mesenchymal markers: vimentin and fibronectin.

As expected from their morphology, MCF-7 cells expressing WT LOXL2, N288Q LOXL2, or the catalytically incompetent K653R LOXL2 (each of which is mostly secreted) expressed the aforementioned markers at levels consistent with the control epithelial cells (Fig. 2C). The cells expressing nuclear associated catalytically incompetent K653S LOXL2 also exhibited an epithelial phenotype, strongly indicating that the EMT observed in cells expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 is LOX amine oxidase-dependent.

We next examined the expression level of claudin-1 and occludin, two tight junction proteins that are essential for maintaining apical-basal cell polarity (34). We found that both proteins were down-regulated in MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2, as well as in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, we did not see down-regulation of these proteins in MCF-7 cells expressing K653S, WT, N288Q, or K653R LOXL2. These results suggest that nuclear-localized LOXL2 contributes to loss-of-polarity of breast cancer cells via down-regulation of claudin-1 and occludin. Altogether, these results suggest that expression of N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 contributes to EMT in these cells.

Snail1 Is Stabilized at the Protein Level in MCF-7 Cells Expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2

Snail1 transcription factor directly represses E-cadherin, occludin, claudin-1, and estrogen receptor α (ERα) by binding to a corresponding regulatory sequence at the 5′ end of each gene (35–38). In epithelial cells undergoing EMT, Snail1 also binds to the fibronectin (FN1) promoter together with p65 unit of NF-κB and PARP1 to up-regulate its transcription (39). Expression of Snail1 is also tightly correlated with expression of vimentin (40–42). Because we detected down-regulation of E-cadherin, occludin, and claudin-1, as well as up-regulation of fibronectin and vimentin, we hypothesized that Snail1 is highly likely the gatekeeper through which nuclear associated LOXL2 induces EMT, analogous to the hypothesis described by Peinado and co-workers (17). To evaluate this hypothesis, we determined the level of ERα protein expression and found that ERα was almost absent in MCF-7 cells stably expressing N455Q or N644Q LOXL2, as well as in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2C). In contrast, untransfected MCF-7 cells and the remaining stable MCF-7 cells remained positive for ERα. We also checked the expression of E-cadherin, occludin, ERα, vimentin, and fibronectin at the mRNA level by qRT-PCR and observed that E-cadherin, occludin, and ERα are transcriptionally down-regulated, whereas vimentin and fibronectin are transcriptionally up-regulated in cells expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 (Fig. 2D). These results strongly indicate that nuclear associated and catalytically competent LOXL2 switches on Snail1-governed oncogenic signaling pathways. To determine whether LOXL2 regulates Snail1 at the transcriptional level, we next checked the mRNA levels of SNAI1 by qRT-PCR. We did not detect any mRNA up-regulation in the mesenchymal cells, indicating that nuclear associated LOXL2 does not regulate Snail1 at the transcriptional level (Fig. 2D).

Peinado et al. (17, 43) hypothesized that intracellular LOXL2 stabilizes Snail1 protein by oxidizing Lys-98 and/or Lys-137, leading to an undefined conformational change that protects Snail1 from phosphorylation by GSK3β. We detected up-regulation of Snail1 protein in MCF-7 cells stably expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2, where the protein level of Snail1 was even higher than in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2E). In contrast, GSK3β was noticeably down-regulated in MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2, similar to MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2E). The reduced expression level of GSK3β in these invasive cells may contribute to the stabilization of Snail1. Finally, we examined the stability of Snail1 by arresting protein synthesis with CHX. In MCF-7 cells stably expressing N644Q LOXL2, detectable Snail1 protein levels persisted for up to 6 h (Fig. 2F), whereas in cells expressing N455Q, Snail1 could not be detected at the 6-h time point. This is consistent with the slight increase in Snail1 protein observed in cells expressing N644Q LOXL2 (Fig. 2E). Experiments to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 increase Snail1 protein concentration are underway.

Cells Expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 Are Highly Invasive

Using a Matrigel in vitro Transwell invasion assay, we examined the invasiveness of stable MCF-7 cells in comparison with empty vector-transfected MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2G). MCF-7 cells stably expressing nuclear associated N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 were highly invasive as compared with cells transfected with empty vector (p < 0.0001) and were also more invasive than MDA-MB-231 cells. On the other hand, the invasiveness of MCF-7 cells expressing K653S LOXL2 was not statistically distinguishable from empty vector-transfected MCF-7 cells. To ensure that the apparent invasiveness was not the byproduct of increased cell proliferation, we examined the expression level of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) by immunoblot. PCNA levels at 2 days after seeding (i.e. the timeframe during which the Matrigel invasion assay was performed) did not vary significantly among the cell lines (data not shown). Thus, as with EMT, it appears that the catalytic activity of nuclear associated LOXL2 plays an essential role in promoting breast cancer cell invasion in vitro.

Notably, although we did not detect mesenchymal markers in the MCF-7 cells stably expressing WT LOXL2 (Fig. 2C), this cell line exhibited statistically significant invasiveness (p < 0.05) relative to the negative control. This supports a previous study reporting that MCF-7 cells stably transfected with WT LOXL2 and transplanted into the mammary fat pads of nude mice were shown to invade other tissues and organs (4). However, further study is necessary to determine whether the invasiveness of MCF-7 cells expressing WT LOXL2 (which is mostly secreted) is due to the secreted LOXL2 or reflects the presence of the nuclear associated ∼75-kDa LOXL2 (Fig. 2B).

N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 Up-regulate MT1-MMP

To gain insight into why MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 were more invasive than those expressing primarily secreted LOXL2 or catalytically inactive intracellular LOXL2, we conducted immunoblot experiments to examine the expression levels of MMPs that have been linked to breast cancer metastasis/invasion, namely MMP-2, MMP-9, and MT1-MMP (MMP-14) (44–46). Among these MMPs, Snail1 has been shown to up-regulate MMP-2 and MT1-MMP in hepatocellular and pancreatic ductal carcinomas (47, 48). We observed up-regulation of MT1-MMP in MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 (Fig. 2H). MT1-MMP is a transmembrane MMP that activates MMP-2 and MMP-9 by processing pro-MMP2 and pro-MMP9 secreted from fibroblasts in the vicinity of tumor cells to facilitate degradation of ECM proteins (46, 49, 50). MT1-MMP can also directly degrade ECM proteins and plays an essential role in the invasion of ovarian cancer cells (51). Because cell invasion was examined in the absence of fibroblasts, the MT1-MMP produced by invasive MCF-7 cells is likely to be directly involved in Matrigel degradation.

That MCF-7 cells stably expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 were even more invasive than basal-like MDA-MB-231 cells deserves some discussion. Tumor cells are known to penetrate three-dimensional matrices in two different manners of invasion: mesenchymal-like or amoeboid-like. The former employs MMP-catalyzed matrix degradation, whereas the latter is protease-independent and relies on actinomyosin contractility (52, 53). MDA-MB-231 cells have been shown to invade three-dimensional Matrigel primarily by amoeboid locomotion (54, 55). The up-regulation of fibronectin and MT1-MMP in the MCF-7 cells expressing N455Q and N644Q LOXL2 would be consistent with mesenchymal-like locomotion and may account for some of the disparity in cell invasiveness as compared with MDA-MB-231 cells, where these proteins were not up-regulated. Confirmation of the mechanism by which these MCF-7 cells invade requires further study.

Conclusion

We detected two forms of endogenous LOXL2 in basal-like MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells: ∼100-kDa LOXL2, which is N-glycosylated and secreted, and ∼75-kDa LOXL2, which is nonglycosylated and intracellular. The latter has an apparent affinity for the nucleus. By manipulating the PTMs of LOXL2 (e.g. N-glycosylation and LTQ cofactor formation), we were able to select MCF-7 cells stably expressing recombinant LOXL2s differing in their subcellular localizations and catalytic competencies. This enabled us to dissect the functions of intracellular and extracellular LOXL2 and independently assess their contributions to EMT and cell invasion. Here, we demonstrated that in cells expressing nuclear associated nonglycosylated (∼75-kDa) LOXL2, Snail1 protein was stabilized in a LOX amine oxidase-dependent fashion. This Snail1 stabilization induced EMT by down-regulation of epithelial markers and up-regulation of mesenchymal markers and additionally promoted in vitro invasion via activation of vimentin, fibronectin, and MT1-MMP. In contrast, cells expressing secreted N-glycosylated LOXL2 exhibited an epithelial phenotype and relatively low invasiveness under our in vitro experimental conditions. We speculate that the consequences of overexpressing secreted LOXL2, which have been documented elsewhere (4, 10, 13), may require a longer time frame and a tumor microenvironment with complex interactions between LOXL2 and proteins secreted by fibroblasts (e.g. ECM structural proteins, MMP-2/MMP-9, and other proteins) to alter mechanotransduction of breast cancer cells to induce EMT and promote invasion in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heather Shinogle for technical assistance in microscopic image acquisition, and Tomoo Iwakuma for invaluable insight and suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P20 RR015563 (to M. M., Center of Biomedical Research Excellence for Cancer Experimental Therapeutics), GM079446-02 (to M. M.), and P30-CA168524 (to D. R. W.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Grant AHA0765445Z (to M. M.) and National Science Foundation Grant CAREER MCB-0747377 (to M. M.).

- LOX

- lysyl oxidase

- LOXL2

- lysyl oxidase-like 2

- LTQ

- lysine tyrosylquinone

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- SRCR

- scavenger receptor cysteine-rich

- EMT

- epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- GSK3β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3 β

- PNGase F

- peptide-N-glycosidase F

- Endo H

- endoglycosidase H

- ERα

- estrogen receptor α

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- SFM

- serum-free medium

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- HEPBS

- N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(4-butanesulfonic acid).

REFERENCES

- 1. Csiszar K. (2001) Lysyl oxidases: a novel multifunctional amine oxidase family. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 70, 1–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith-Mungo L. I., Kagan H. M. (1998) Lysyl oxidase: properties, regulation and multiple functions in biology. Matrix Biol. 16, 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang S. X., Mure M., Medzihradszky K. F., Burlingame A. L., Brown D. E., Dooley D. M., Smith A. J., Kagan H. M., Klinman J. P. (1996) A crosslinked cofactor in lysyl oxidase: redox function for amino acid side chains. Science 273, 1078–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akiri G., Sabo E., Dafni H., Vadasz Z., Kartvelishvily Y., Gan N., Kessler O., Cohen T., Resnick M., Neeman M., Neufeld G. (2003) Lysyl oxidase-related protein-1 promotes tumor fibrosis and tumor progression in vivo. Cancer Res. 63, 1657–1666 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kirschmann D. A., Seftor E. A., Fong S. F., Nieva D. R., Sullivan C. M., Edwards E. M., Sommer P., Csiszar K., Hendrix M. J. (2002) A molecular role for lysyl oxidase in breast cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 62, 4478–4483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker A. M., Bird D., Lang G., Cox T. R., Erler J. T. (2013) Lysyl oxidase enzymatic function increases stiffness to drive colorectal cancer progression through FAK. Oncogene 32, 1863–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Erler J. T., Bennewith K. L., Cox T. R., Lang G., Bird D., Koong A., Le Q. T., Giaccia A. J. (2009) Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell 15, 35–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kass L., Erler J. T., Dembo M., Weaver V. M. (2007) Mammary epithelial cell: influence of extracellular matrix composition and organization during development and tumorigenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 1987–1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levental K. R., Yu H., Kass L., Lakins J. N., Egeblad M., Erler J. T., Fong S. F., Csiszar K., Giaccia A., Weninger W., Yamauchi M., Gasser D. L., Weaver V. M. (2009) Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 139, 891–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barker H. E., Chang J., Cox T. R., Lang G., Bird D., Nicolau M., Evans H. R., Gartland A., Erler J. T. (2011) LOXL2-mediated matrix remodeling in metastasis and mammary gland involution. Cancer Res. 71, 1561–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Payne S. L., Fogelgren B., Hess A. R., Seftor E. A., Wiley E. L., Fong S. F., Csiszar K., Hendrix M. J., Kirschmann D. A. (2005) Lysyl oxidase regulates breast cancer cell migration and adhesion through a hydrogen peroxide-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 65, 11429–11436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peng L., Ran Y. L., Hu H., Yu L., Liu Q., Zhou Z., Sun Y. M., Sun L. C., Pan J., Sun L. X., Zhao P., Yang Z. H. (2009) Secreted LOXL2 is a novel therapeutic target that promotes gastric cancer metastasis via the Src/FAK pathway. Carcinogenesis 30, 1660–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barry-Hamilton V., Spangler R., Marshall D., McCauley S., Rodriguez H. M., Oyasu M., Mikels A., Vaysberg M., Ghermazien H., Wai C., Garcia C. A., Velayo A. C., Jorgensen B., Biermann D., Tsai D., Green J., Zaffryar-Eilot S., Holzer A., Ogg S., Thai D., Neufeld G., Van Vlasselaer P., Smith V. (2010) Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat. Med. 16, 1009–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cano A., Santamaría P. G., Moreno-Bueno G. (2012) LOXL2 in epithelial cell plasticity and tumor progression. Future Oncol. 8, 1095–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moreno-Bueno G., Salvador F., Martín A., Floristán A., Cuevas E. P., Santos V., Montes A., Morales S., Castilla M. A., Rojo-Sebastián A., Martínez A., Hardisson D., Csiszar K., Portillo F., Peinado H., Palacios J., Cano A. (2011) Lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2), a new regulator of cell polarity required for metastatic dissemination of basal-like breast carcinomas. EMBO Mol. Med. 3, 528–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peinado H., Moreno-Bueno G., Hardisson D., Pérez-Gómez E., Santos V., Mendiola M., de Diego J. I., Nistal M., Quintanilla M., Portillo F., Cano A. (2008) Lysyl oxidase-like 2 as a new poor prognosis marker of squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 68, 4541–4550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peinado H., Del Carmen Iglesias-de la Cruz M., Olmeda D., Csiszar K., Fong K. S., Vega S., Nieto M. A., Cano A., Portillo F. (2005) A molecular role for lysyl oxidase-like 2 enzyme in Snail regulation and tumor progression. EMBO J. 24, 3446–3458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herranz N., Dave N., Millanes-Romero A., Morey L., Díaz V. M., Lórenz-Fonfría V., Gutierrez-Gallego R., Jerónimo C., Di Croce L., García de Herreros A., Peiró S. (2012) Lysyl oxidase-like 2 deaminates lysine 4 in histone H3. Mol. Cell 46, 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu L., Go E. P., Finney J., Moon H., Lantz M., Rebecchi K., Desaire H., Mure M. (2013) Post-translational modifications of recombinant human lysyl oxidase-like 2 (rhLOXL2) secreted from Drosophila S2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5357–5363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palamakumbura A. H., Trackman P. C. (2002) A fluorometric assay for detection of lysyl oxidase enzyme activity in biological samples. Anal. Biochem. 300, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollosi P., Yakushiji J. K., Fong K. S., Csiszar K., Fong S. F. (2009) Lysyl oxidase-like 2 promotes migration in noninvasive breast cancer cells but not in normal breast epithelial cells. Int. J. Cancer 125, 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rebecchi K. R., Go E. P., Xu L., Woodin C. L., Mure M., Desaire H. (2011) A general protease digestion procedure for optimal protein sequence coverage and post-translational modifications analysis of recombinant glycoproteins: application to the characterization of human lysyl oxidase-like 2 glycosylation. Anal. Chem. 83, 8484–8491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bence M., Sahin-Tóth M. (2011) Asparagine-linked glycosylation of human chymotrypsin C is required for folding and secretion but not for enzyme activity. FEBS J. 278, 4338–4350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petrecca K., Atanasiu R., Akhavan A., Shrier A. (1999) N-Linked glycosylation sites determine HERG channel surface membrane expression. J. Physiol. 515, 41–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stanley P., Schachter H., Taniguchi N. (2009) Chapter 8, N-Glycans. in Essentials of Glycobiology (Varki A., Cummings R., Esko J., Freeze H. H., Stanley P., Bertozzi C., Hart G., Etzler M. eds), Second Ed., pp. 101–114, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polevoda B., Sherman F. (2003) N-terminal acetyltransferases and sequence requirements for N-terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 325, 595–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodriguez H. M., Vaysberg M., Mikels A., McCauley S., Velayo A. C., Garcia C., Smith V. (2010) Modulation of lysyl oxidase-like 2 enzymatic activity by an allosteric antibody inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20964–20974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tang S. S., Trackman P. C., Kagan H. M. (1983) Reaction of aortic lysyl oxidase with β-aminopropionitrile. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 4331–4338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bollinger J. A., Brown D. E., Dooley D. M. (2005) The formation of lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ) is a self-processing reaction. Expression and characterization of a Drosophila lysyl oxidase. Biochemistry 44, 11708–11714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tu B. P., Weissman J. S. (2004) Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences. J. Cell Biol. 164, 341–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moore R. H., Spies M. A., Culpepper M. B., Murakawa T., Hirota S., Okajima T., Tanizawa K., Mure M. (2007) Trapping of a dopaquinone intermediate in the TPQ cofactor biogenesis in a copper-containing amine oxidase from Arthrobacter globiformis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 11524–11534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mure M., Wang S. X., Klinman J. P. (2003) Synthesis and characterization of model compounds of the lysine tyrosyl quinone cofactor of lysyl oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6113–6125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tang C., Klinman J. P. (2001) The catalytic function of bovine lysyl oxidase in the absence of copper. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30575–30578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martin-Belmonte F., Perez-Moreno M. (2012) Epithelial cell polarity, stem cells and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 23–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Batlle E., Sancho E., Francí C., Domínguez D., Monfar M., Baulida J., García De Herreros A. (2000) The transcription factor Snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cano A., Pérez-Moreno M. A., Rodrigo I., Locascio A., Blanco M. J., del Barrio M. G., Portillo F., Nieto M. A. (2000) The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dhasarathy A., Kajita M., Wade P. A. (2007) The transcription factor Snail mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transitions by repression of estrogen receptor-α. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 2907–2918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martínez-Estrada O. M., Cullerés A., Soriano F. X., Peinado H., Bolós V., Martínez F. O., Reina M., Cano A., Fabre M., Vilaró S. (2006) The transcription factors Slug and Snail act as repressors of Claudin-1 expression in epithelial cells. Biochem. J. 394, 449–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stanisavljevic J., Porta-de-la-Riva M., Batlle R., de Herreros A. G., Baulida J. (2011) The p65 subunit of NF-κB and PARP1 assist Snail1 in activating fibronectin transcription. J. Cell Sci. 124, 4161–4171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin C. Y., Tsai P. H., Kandaswami C. C., Lee P. P., Huang C. J., Hwang J. J., Lee M. T. (2011) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 cooperates with transcription factor Snail to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Sci. 102, 815–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mendez M. G., Kojima S., Goldman R. D. (2010) Vimentin induces changes in cell shape, motility, and adhesion during the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. FASEB J. 24, 1838–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Olmeda D., Jordá M., Peinado H., Fabra A., Cano A. (2007) Snail silencing effectively suppresses tumour growth and invasiveness. Oncogene 26, 1862–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peinado H., Portillo F., Cano A. (2005) Switching on-off Snail: LOXL2 versus GSK3β. Cell Cycle 4, 1749–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim E. S., Kim J. S., Kim S. G., Hwang S., Lee C. H., Moon A. (2011) Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and breast cell invasion through S1P3-Gαq coupling. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2220–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miyazawa Y., Uekita T., Ito Y., Seiki M., Yamaguchi H., Sakai R. (2013) CDCP1 regulates the function of MT1-MMP and invadopodia-mediated invasion of cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 11, 628–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Toth M., Chvyrkova I., Bernardo M. M., Hernandez-Barrantes S., Fridman R. (2003) Pro-MMP-9 activation by the MT1-MMP/MMP-2 axis and MMP-3: role of TIMP-2 and plasma membranes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308, 386–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miyoshi A., Kitajima Y., Sumi K., Sato K., Hagiwara A., Koga Y., Miyazaki K. (2004) Snail and SIP1 increase cancer invasion by upregulating MMP family in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Br. J. Cancer 90, 1265–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shields M. A., Dangi-Garimella S., Krantz S. B., Bentrem D. J., Munshi H. G. (2011) Pancreatic cancer cells respond to type I collagen by inducing Snail expression to promote membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase-dependent collagen invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 10495–10504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saad S., Gottlieb D. J., Bradstock K. F., Overall C. M., Bendall L. J. (2002) Cancer cell-associated fibronectin induces release of matrix metalloproteinase-2 from normal fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 62, 283–289 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Welm B., Mott J., Werb Z. (2002) Developmental biology: vasculogenesis is a wreck without RECK. Curr. Biol. 12, R209–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sodek K. L., Ringuette M. J., Brown T. J. (2007) MT1-MMP is the critical determinant of matrix degradation and invasion by ovarian cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 97, 358–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sanz-Moreno V., Marshall C. J. (2010) The plasticity of cytoskeletal dynamics underlying neoplastic cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 690–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wolf K., Mazo I., Leung H., Engelke K., von Andrian U. H., Deryugina E. I., Strongin A. Y., Bröcker E. B., Friedl P. (2003) Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal-amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J. Cell Biol. 160, 267–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Poincloux R., Collin O., Lizárraga F., Romao M., Debray M., Piel M., Chavrier P. (2011) Contractility of the cell rear drives invasion of breast tumor cells in 3D Matrigel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1943–1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Terry S. J., Elbediwy A., Zihni C., Harris A. R., Bailly M., Charras G. T., Balda M. S., Matter K. (2012) Stimulation of cortical myosin phosphorylation by p114RhoGEF drives cell migration and tumor cell invasion. PLoS One 7, e50188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]