Abstract

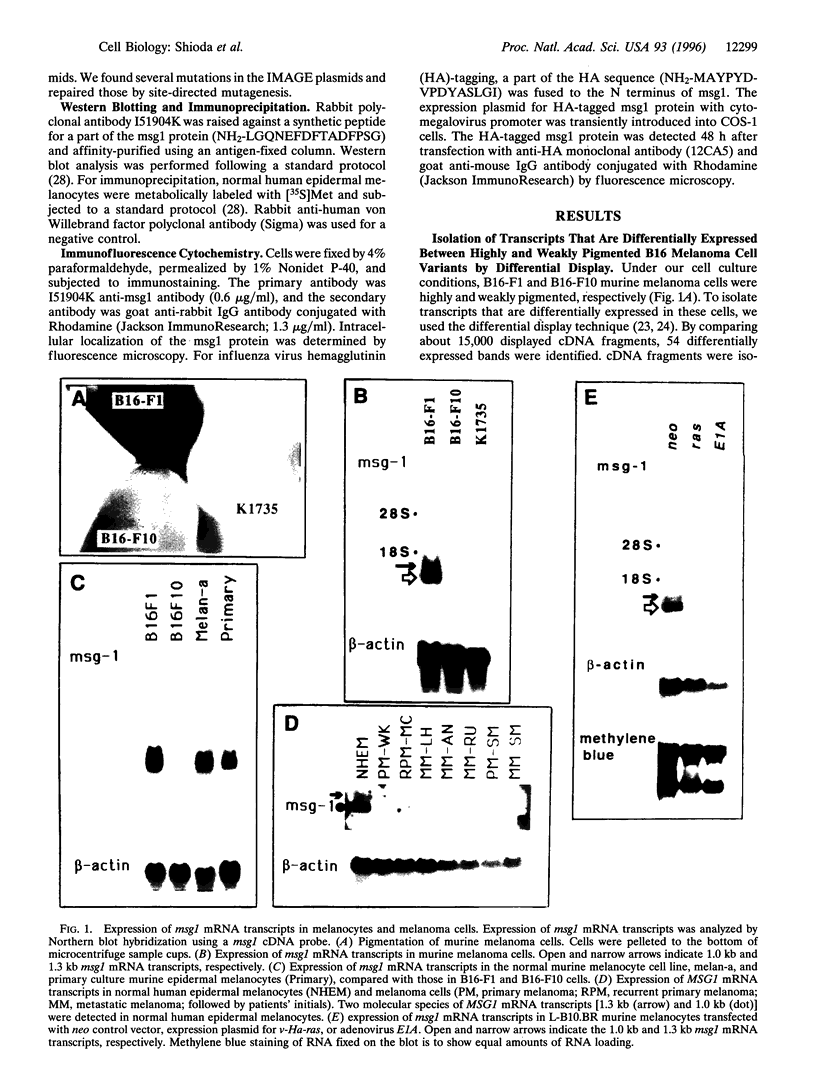

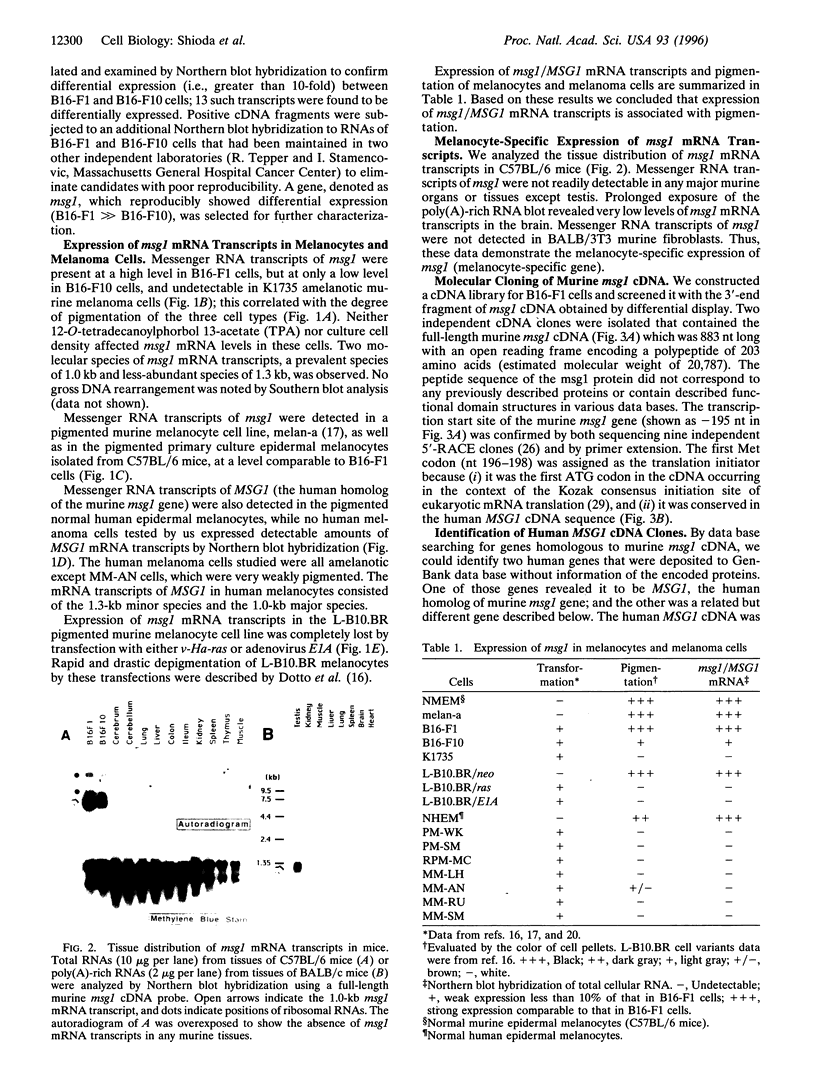

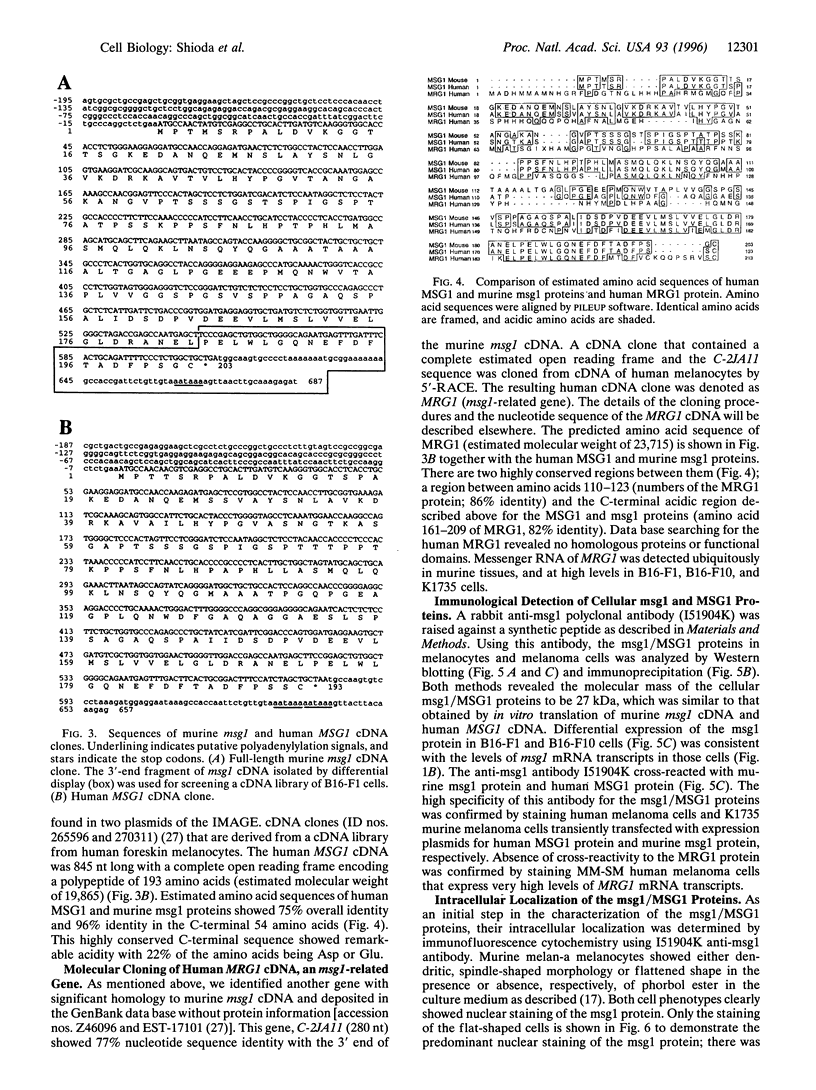

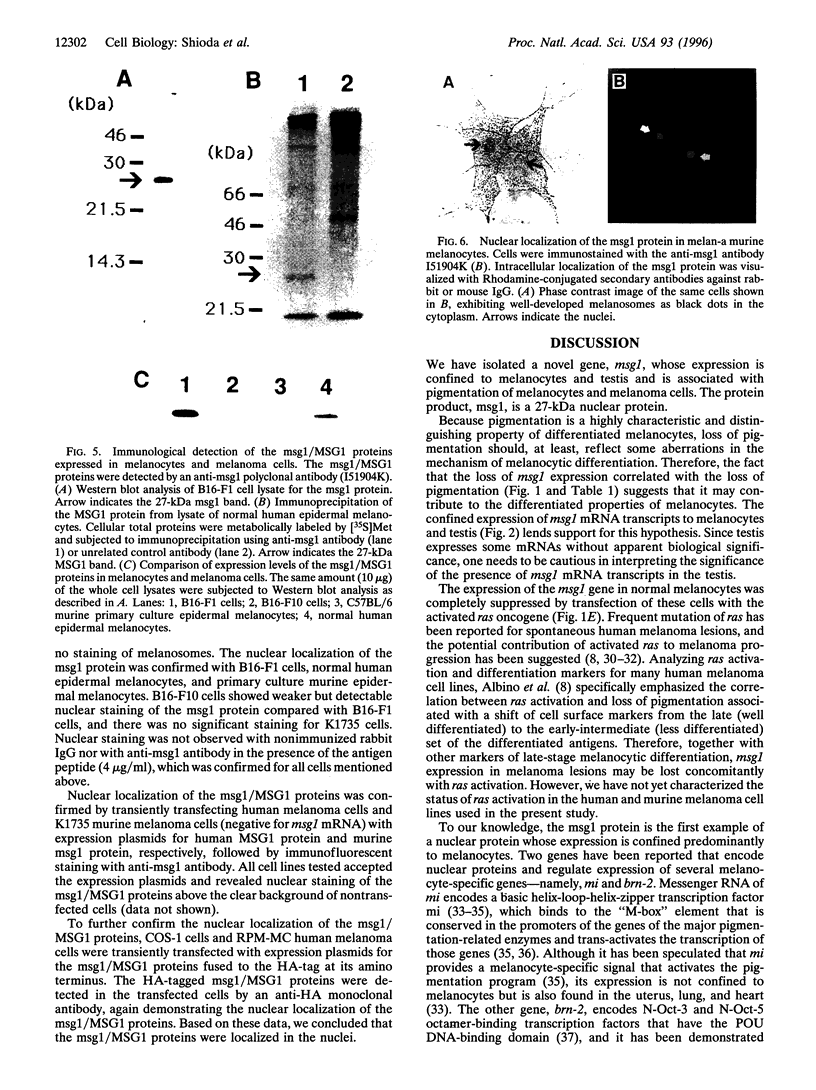

Messenger RNA transcripts of the highly pigmented murine melanoma B16-F1 cells were compared with those from their weakly pigmented derivative B16-F10 cells by differential display. A novel gene called msg1 (melanocyte-specific gene) was found to be expressed at high levels in B16-F1 cells but at low levels in B16-F10 cells. Expression of msg1 was undetectable in the amelanotic K1735 murine melanoma cells. The pigmented murine melanocyte cell line melan-a expressed msg1, as did pigmented primary cultures of murine and human melanocytes; however, seven amelanotic or very weakly pigmented human melanoma cell lines were negative. Transformation of murine melanocytes by transfection with v-Ha-ras or Ela was accompanied by depigmentation and led to complete loss of msg1 expression. The normal tissue distribution of msg1 mRNA transcripts in adult mice was confined to melanocytes and testis. Murine msg1 and human MSG1 genes encode a predicted protein of 27 kDa with 75% overall amino acid identity and 96% identity within the C-terminal acidic domain of 54 amino acids. This C-terminal domain was conserved with 76% amino acid identity in another protein product of a novel human gene, MRG1 (msg1-related gene), isolated from normal human melanocyte cDNA by 5'-rapid amplification of cDNA ends based on the homology to msg1. The msg1 protein was localized to the melanocyte nucleus by immunofluorescence cytochemistry. We conclude that msg1 encodes a nuclear protein, is melanocyte-specific, and appears to be lost in depigmented melanoma cells.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Albino A. P., Nanus D. M., Mentle I. R., Cordon-Cardo C., McNutt N. S., Bressler J., Andreeff M. Analysis of ras oncogenes in malignant melanoma and precursor lesions: correlation of point mutations with differentiation phenotype. Oncogene. 1989 Nov;4(11):1363–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D. C. Colour genes, oncogenes and melanocyte differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1991 Feb;98(Pt 2):135–139. doi: 10.1242/jcs.98.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D. C., Cooper P. J., Hart I. R. A line of non-tumorigenic mouse melanocytes, syngeneic with the B16 melanoma and requiring a tumour promoter for growth. Int J Cancer. 1987 Mar 15;39(3):414–418. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D. C., Dexter T. J., Ormerod E. J., Hart I. R. Increased experimental metastatic capacity of a murine melanoma following induction of differentiation. Cancer Res. 1986 Jul;46(7):3239–3244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D. C. Genetics, development, and malignancy of melanocytes. Int Rev Cytol. 1993;146:191–260. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley N. J., Eisen T., Goding C. R. Melanocyte-specific expression of the human tyrosinase promoter: activation by the microphthalmia gene product and role of the initiator. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Dec;14(12):7996–8006. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers H. R., Etoh T., Doherty J. R., Sober A. J., Mihm M. C., Jr Cell migration and actin organization in cultured human primary, recurrent cutaneous and metastatic melanoma. Time-lapse and image analysis. Am J Pathol. 1991 Aug;139(2):423–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou P. Y., Fasman G. D. Empirical predictions of protein conformation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. H., Jr, Elder D. E., Guerry D., 4th, Epstein M. N., Greene M. H., Van Horn M. A study of tumor progression: the precursor lesions of superficial spreading and nodular melanoma. Hum Pathol. 1984 Dec;15(12):1147–1165. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. H. Tumour progression and the nature of cancer. Br J Cancer. 1991 Oct;64(4):631–644. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotto G. P., Moellmann G., Ghosh S., Edwards M., Halaban R. Transformation of murine melanocytes by basic fibroblast growth factor cDNA and oncogenes and selective suppression of the transformed phenotype in a reconstituted cutaneous environment. J Cell Biol. 1989 Dec;109(6 Pt 1):3115–3128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen T., Easty D. J., Bennett D. C., Goding C. R. The POU domain transcription factor Brn-2: elevated expression in malignant melanoma and regulation of melanocyte-specific gene expression. Oncogene. 1995 Nov 16;11(10):2157–2164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler I. J., Gruys E., Cifone M. A., Barnes Z., Bucana C. Demonstration of multiple phenotypic diversity in a murine melanoma of recent origin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981 Oct;67(4):947–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler I. J. Selection of successive tumour lines for metastasis. Nat New Biol. 1973 Apr 4;242(118):148–149. doi: 10.1038/newbio242148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel A. D., Kim P. S. Modular structure of transcription factors: implications for gene regulation. Cell. 1991 May 31;65(5):717–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90378-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohman M. A., Dush M. K., Martin G. R. Rapid production of full-length cDNAs from rare transcripts: amplification using a single gene-specific oligonucleotide primer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Dec;85(23):8998–9002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlich D., Mattaj I. W. Nucleocytoplasmic transport. Science. 1996 Mar 15;271(5255):1513–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Treacy M. N., Simmons D. M., Ingraham H. A., Swanson L. W., Rosenfeld M. G. Expression of a large family of POU-domain regulatory genes in mammalian brain development. Nature. 1989 Jul 6;340(6228):35–41. doi: 10.1038/340035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemesath T. J., Steingrímsson E., McGill G., Hansen M. J., Vaught J., Hodgkinson C. A., Arnheiter H., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Fisher D. E. microphthalmia, a critical factor in melanocyte development, defines a discrete transcription factor family. Genes Dev. 1994 Nov 15;8(22):2770–2780. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlyn M., Kath R., Williams N., Valyi-Nagy I., Rodeck U. Growth-regulatory factors for normal, premalignant, and malignant human cells in vitro. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;54:213–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60812-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson C. A., Moore K. J., Nakayama A., Steingrímsson E., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Arnheiter H. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell. 1993 Jul 30;74(2):395–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90429-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. J., Lingrel J. B., Krakowsky J. M., Anderson K. P. A helix-loop-helix transcription factor-like gene is located at the mi locus. J Biol Chem. 1993 Oct 5;268(28):20687–20690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Lin J. J., Su Z. Z., Goldstein N. I., Fisher P. B. Subtraction hybridization identifies a novel melanoma differentiation associated gene, mda-7, modulated during human melanoma differentiation, growth and progression. Oncogene. 1995 Dec 21;11(12):2477–2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Lin J., Su Z. Z., Herlyn M., Kerbel R. S., Weissman B. E., Welch D. R., Fisher P. B. The melanoma differentiation-associated gene mda-6, which encodes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, is differentially expressed during growth, differentiation and progression in human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 1995 May 4;10(9):1855–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Lin J., Young S. M., Goldstein N. I., Waxman S., Davila V., Chellappan S. P., Fisher P. B. Cell cycle gene expression and E2F transcription factor complexes in human melanoma cells induced to terminally differentiate. Oncogene. 1995 Sep 21;11(6):1179–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbel R. S. Growth dominance of the metastatic cancer cell: cellular and molecular aspects. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;55:87–132. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: an update. J Cell Biol. 1989 Feb;108(2):229–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider J. W., Schmoyer M. E. Spontaneous maturation and differentiation of B16 melanoma cells in culture. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975 Sep;55(3):641–647. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.3.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon G., Auffray C., Polymeropoulos M., Soares M. B. The I.M.A.G.E. Consortium: an integrated molecular analysis of genomes and their expression. Genomics. 1996 Apr 1;33(1):151–152. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P., Averboukh L., Pardee A. B. Distribution and cloning of eukaryotic mRNAs by means of differential display: refinements and optimization. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993 Jul 11;21(14):3269–3275. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P., Pardee A. B. Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992 Aug 14;257(5072):967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. J., Tjian R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science. 1989 Jul 28;245(4916):371–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2667136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortonne J. P. Retinoic acid and pigment cells: a review of in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Br J Dermatol. 1992 Sep;127 (Suppl 41):43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb16987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J. A., Loganzo F., Jr, Shea C. R., Walker G. J., Flores J. F., Glendening J. M., Bogdany J. K., Shiel M. J., Haluska F. G., Fountain J. W. Loss of expression of the p16/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2 tumor suppressor gene in melanocytic lesions correlates with invasive stage of tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1995 Jul 1;55(13):2713–2718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer M., Edmundson A. B. Use of helical wheels to represent the structures of proteins and to identify segments with helical potential. Biophys J. 1967 Mar;7(2):121–135. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(67)86579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shioda T., Ohta T., Isselbacher K. J., Rhoads D. B. Differentiation-dependent expression of the Na+/glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) in LLC-PK1 cells: role of protein kinase C activation and ongoing transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Dec 6;91(25):11919–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla V. K., Hughes D. C., Hughes L. E., McCormick F., Padua R. A. ras mutations in human melanotic lesions: K-ras activation is a frequent and early event in melanoma development. Oncogene Res. 1989;5(2):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soballe P. W., Herlyn M. Cellular pathways leading to melanoma differentiation: therapeutic implications. Melanoma Res. 1994 Aug;4(4):213–223. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura A., Halaban R., Moellmann G., Cowan J. M., Lerner M. R., Lerner A. B. Normal murine melanocytes in culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1987 Jul;23(7):519–522. doi: 10.1007/BF02628423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J. A., Murphy K., Baker E., Sutherland G. R., Parsons P. G., Sturm R. A., Thomson F. The brn-2 gene regulates the melanocytic phenotype and tumorigenic potential of human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 1995 Aug 17;11(4):691–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H., Kobayashi H., Ohkawara A., Kuzumaki N. Differential expression of ras oncogene products among the types of human melanomas and melanocytic nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 1989 Jul;93(1):54–59. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van 't Veer L. J., Burgering B. M., Versteeg R., Boot A. J., Ruiter D. J., Osanto S., Schrier P. I., Bos J. L. N-ras mutations in human cutaneous melanoma from sun-exposed body sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Jul;9(7):3114–3116. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]