Background: Receptor-activating autoantibodies are associated with various cardiovascular diseases.

Results: A human monoclonal autoantibody isolated from a patient with idiopathic postural hypotension activates the β2-adrenergic receptor and induces potent vasodilatation.

Conclusion: This antibody demonstrates sufficient activity to produce postural hypotension in its host.

Significance: This is the first human monoclonal autoantibody that activates an autonomic receptor.

Keywords: Adrenergic Receptor, Autoimmunity, Cardiovascular Disease, Pathogenesis, Vascular, Human Monoclonal Autoantibody, Postural Hypotension, Vasodilatory

Abstract

Functional autoantibodies to the autonomic receptors are increasingly recognized in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases. To date, no human activating monoclonal autoantibodies to these receptors have been available. In this study, we describe for the first time a β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR)-activating monoclonal autoantibody (C5F2) produced from the lymphocytes of a patient with idiopathic postural hypotension. C5F2, an IgG3 isotype, recognizes an epitope in the N terminus of the second extracellular loop (ECL2) of β2AR. Surface plasmon resonance analysis revealed high binding affinity for the β2AR ECL2 peptide. Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence demonstrated specific binding to β2AR in H9c2 cardiomyocytes, CHO cells expressing human β2AR, and rat aorta. C5F2 stimulated cyclic AMP production in β2AR-transfected CHO cells and induced potent dilation of isolated rat cremaster arterioles, both of which were specifically blocked by the β2AR-selective antagonist ICI-118551 and by the β2AR ECL2 peptide. This monoclonal antibody demonstrated sufficient activity to produce postural hypotension in its host. Its availability provides a unique opportunity to identify previously unrecognized causes and new pharmacological management of postural hypotension and other cardiovascular diseases.

Introduction

Agonistic autoantibodies to the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)2 are increasingly recognized to contribute to disease pathogenesis. The classic example is Graves disease, which is characterized by autoantibodies that activate the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor. Over the past 2 decades, extensive studies have demonstrated that autoimmune activation of GPCR plays an important role in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Activating autoantibodies to the autonomic β1/β2-adrenergic, M2 muscarinic and α1-adrenergic receptors are variably present in patients with cardiomyopathy (1–3), myocarditis (4, 5), hypertension (6–8), and cardiac arrhythmias (9–12). These autoantibodies primarily target the second extracellular loop (ECL2) of their respective receptors to mediate receptor activation (13, 14). The pathological significance of these autoantibodies has been demonstrated in animals immunized with peptides corresponding to ECL2 of β1/β2-adrenergic receptors (15, 16), the M2 muscarinic receptor (17, 18), and the α1-adrenergic receptor (19, 20).

We recently reported the association of vasodilatory polyclonal autoantibodies to the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) and/or M3 muscarinic receptor in postural hypotension patients (21, 22). These autoantibodies possess sufficient bioactivity to alter the postural vascular response, thus contributing to the pathophysiology of postural hypotension, especially the “idiopathic” type, i.e. without known causes.

In this study, we describe a novel human monoclonal anti-β2AR autoantibody derived from a patient with idiopathic postural hypotension. Our report directly links this human IgG autoantibody with a functional in vitro impact on β2AR mediation of smooth muscle vasodilatation. Our evidence supports the hypothesis that autoantibodies play a role in the control of hypotension.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Clinical Description

The patient at 48 years of age developed repetitive episodes of a supraventricular tachycardia and subsequently hypotensive episodes upon standing. During the posture test, he demonstrated a significant drop in systolic/diastolic blood pressure of 52/22 mm Hg and a significant increase in heart rate of 18 beats/min. This was partially diminished when he was placed on the non-selective βAR blocker carvedilol. The patient was not on any immunomodulatory medications at the time. His serum demonstrated significantly elevated titer and functional activity of anti-β2AR autoantibodies (22).

Hybridoma Production

Peripheral lymphocytes were separated from whole blood by Histopaque-1077 Hybri-Max (Sigma) and stimulated for 1 week with pokeweed mitogen (2 μg/ml) in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium containing 10% human AB serum. Cells were washed three times with Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium without serum and fused with HMMA2.11TG/0 cells (human/mouse myeloma cell line) using polyethylene glycol 1000 as described previously (23). Hybridomas were selected by culture in hypoxanthine/aminopterin/thymidine medium and screened by ELISA as described previously (22) using a synthetic peptide (HWYRATHQEAINCYANETCCDFFTNQ) derived from ECL2 of human β2AR (primary accession number P07550). Cloning of hybridomas was achieved by limiting dilution and was performed three times. Established clones were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum. Positive clones were checked for isotype with isotype-specific secondary antibodies (Sigma). This study was approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board, and the subject provided written informed consent.

Epitope Mapping

Epitope mapping for monoclonal antibody C5F2 was performed with Multipin solid-phase peptides (Mimotopes), which comprised a set of 19 octapeptides overlapping by 7 amino acids spanning ECL2 of β2AR. C5F2 IgG (1:50) was added to the wells of a 96-well plate along with the solid-phase peptides and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The peptides were washed with PBS/Tween 20 and incubated with anti-human IgG antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma). The reactivity of C5F2 to the solid-phase peptides was measured by adding tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution in the developing plate. The absorbance values were read at 405 nm.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

SPR measurements were performed on a BIAcore T100 instrument (GE Healthcare). The N-terminally biotinylated β2AR ECL2 peptide (1 mg/ml) was immobilized on a streptavidin-coated sensor chip at a flow rate of 5 μl/min for 5 min. Increasing concentrations of C5F2 (3–100 nm) were injected into the flow cells at 5 μl/min for 12 min in running buffer (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, and 0.005% Surfactant P20), followed by a 5-min dissociation phase with running buffer at the same flow rate. The sensor chip was regenerated with 50 mm NaOH and 1 m NaCl. Affinity, association, and dissociation rate constants were calculated using the BIAevaluation software.

Immunoblotting

H9c2 cardiomyocytes were washed, harvested, and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. Cell lysates with an equal amount of protein (50 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline plus Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with 1 μg/ml C5F2 or rabbit anti-β2AR polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Bound antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). The immunoreaction was quantified by densitometric scanning. C5F2 specificity was tested by preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide (20 μg/ml) for 5 h at room temperature.

Immunostaining

CHO cells expressing human β2AR were cultured on glass coverslips in a 6-well plate for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. For tissue staining, rat aorta frozen sections were fixed with acetone. After blocking, cells or tissue sections were incubated with C5F2, C5F2 pre-absorbed with the β2AR ECL2 peptide, pooled normal human IgG (Sigma), or rabbit anti-β2AR polyclonal antibody (5–10 μg/ml) for 1 h, followed by incubation with FITC-labeled anti-human or anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 META laser scanning confocal microscope.

cAMP Assay

C5F2-mediated β2AR activation of cAMP production in CHO cells was measured using the cAMP Hunter eXpress GPCR assay kit (DiscoveRx) as described (22). Briefly, 30,000 cAMP Hunter eXpress β2AR-expressing CHO cells were dispensed into each well of a 96-well culture plate and incubated overnight. The medium was then removed, and assay buffer containing the cAMP antibody and C5F2 (0.05–500 nm) were sequentially added and incubated for 30 min. C5F2 in the presence of the β2AR-selective blocker ICI-118551, C5F2 pre-absorbed with an excess of the β2AR ECL2 peptide, pooled normal human IgG, and the β-agonist isoproterenol (used as a positive control) were all tested in triplicate. Following sample treatment, cAMP detection reagent and solution were added, and the chemiluminescent signal was read on a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner BioSystems). The cAMP values are expressed as relative luminescence units.

Isolated Arteriole Assay

The vasodilatory effect of C5F2 via activation of β2AR on resistance vessels was examined using an isolated rat cremaster arteriole assay as described (22, 24). Briefly, cremaster arterioles were removed from anesthetized Sprague-Dawley rats (180–250 g). An ∼2-mm segment of the main intramuscular arteriole was microdissected, transferred to a temperature-regulated superfusion chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation), and cannulated at each end with glass micropipettes. Measurements of internal vessel diameter were made using a video edge detector (Model VED-205, Crescent Electronics). After equilibration and development of steady-state myogenic tone, the arterioles were perfused with C5F2 (0.5–500 nm). The β2AR blocker ICI-118551 was then added to the perfusate containing the maximally effective dose of C5F2, and the effect on vessel diameter was recorded. The effects of C5F2 preincubated with the β2AR ECL2 peptide and pooled normal human IgG were also tested. Data are reported as a percentage of the maximal dilatory response to normalize the values. The maximal dilatory response was defined as the increase in diameter from basal tone to the maximal Ca2+-free passive dilation at 70 mm Hg measured at the end of each preparation. This procedure was approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cloning and Sequencing of Ig Variable Regions

RNA was extracted from C5F2 hybridoma cells using an RNAqueous RNA isolation kit (Ambion). One microliter of purified RNA was used for RT-PCR. In brief, RNA was converted to cDNA using a One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). Individual reactions were performed for the human heavy chain (five primers), κ-light chain (four primers), and λ-light chain (eight primers) as detailed for single-cell reactions (25). The reaction mixture was then run on an agarose gel to confirm the presence of a properly sized band and the lack of contamination in the buffer controls. Positive samples were sequenced to obtain V and J gene usage. Finally, another round of PCR was performed using V and J gene-specific primers containing restriction sites for cloning into a transient expression vector (25). Nucleotide alignments with germ-line genes were performed using the sequence analysis tools IgBLAST (26) and IMGT/V-QUEST (27, 28).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. Comparison between individual groups was performed by Student's unpaired t test and one-way analysis of variance, followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Generation of Human Monoclonal Autoantibody

Over 5000 wells were screened for the presence of anti-β2AR antibodies by a β2AR ECL2 peptide-based ELISA. Eleven positive supernatants were selected for retesting to eliminate unstable clones. Two of the 11 supernatants were stably positive, and one single clone (C5F2) was obtained after repeated limiting dilution. C5F2 was found to be of the IgG3 isotype, and secretion has been stable for >6 months.

Epitope Mapping and Binding Characteristics of Monoclonal Antibody C5F2

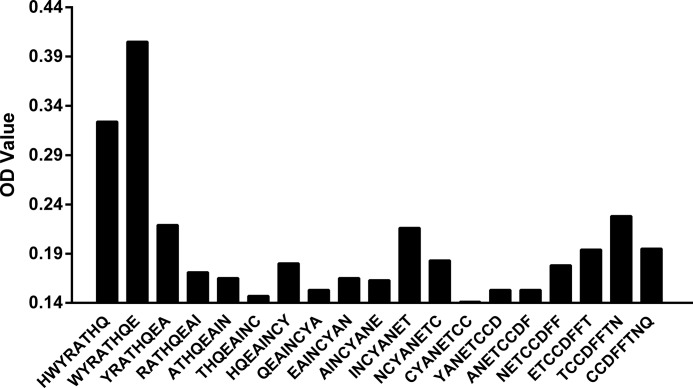

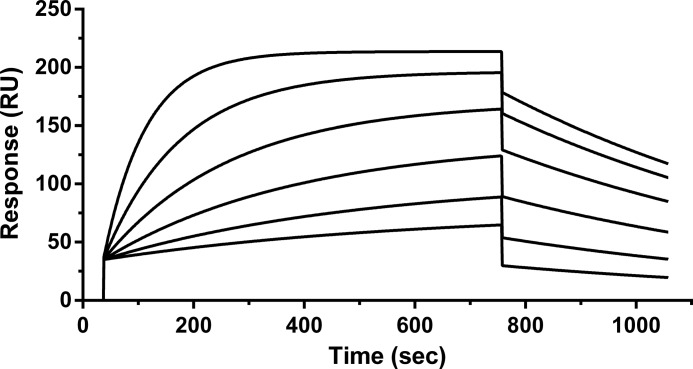

To determine the epitope of C5F2, a set of 19 overlapping peptides covering ECL2 of β2AR were synthesized and tested for their reactivity with C5F2. The only sequence recognized by C5F2 was HWYRATHQE, which is located at the N terminus of β2AR ECL2 (Fig. 1) and which is similar to the reported epitope of an agonistic mouse monoclonal antibody against human β2AR (29). The binding affinity and kinetics of C5F2 were analyzed by SPR using a BIAcore instrument. The sensorgrams showing interaction of increasing concentrations of C5F2 with the immobilized biotinylated β2AR ECL2 peptide (Fig. 2) demonstrated a high binding affinity (KD = 13 nm) of C5F2 for the peptide. SPR measurements yielded an equilibrium constant of 7.8 × 107 m−1, with an association rate constant of 1.1 × 105 m−1 s−1 and a dissociation rate constant of 1.4 × 10−3 s−1.

FIGURE 1.

Monoclonal antibody C5F2 epitope mapping. Epitope determination was performed by ELISA using a Multipin peptide set of 19 overlapping octapeptides spanning human β2AR ECL2. C5F2 reacted predominantly with peptides HWYRATHQ and WYRATHQE at the N terminus of β2AR ECL2.

FIGURE 2.

SPR sensorgrams of C5F2 binding to the peptide. The sensorgrams were generated by injecting increasing concentrations (3.1, 6.2, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 nm) of C5F2 onto the immobilized β2AR ECL2 peptide. The SPR response was measured in resonance units (RU) versus time. Binding constants were calculated using the BIAevaluation software.

Receptor Binding of C5F2

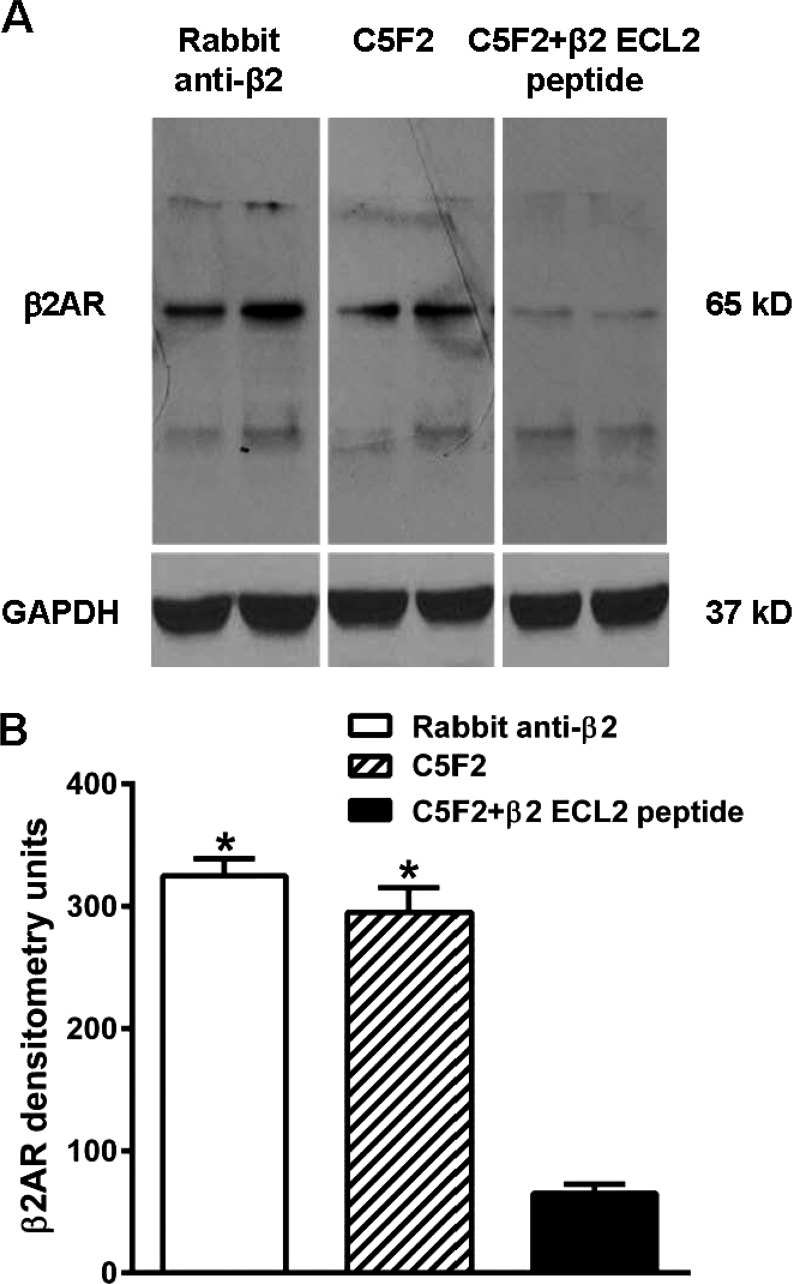

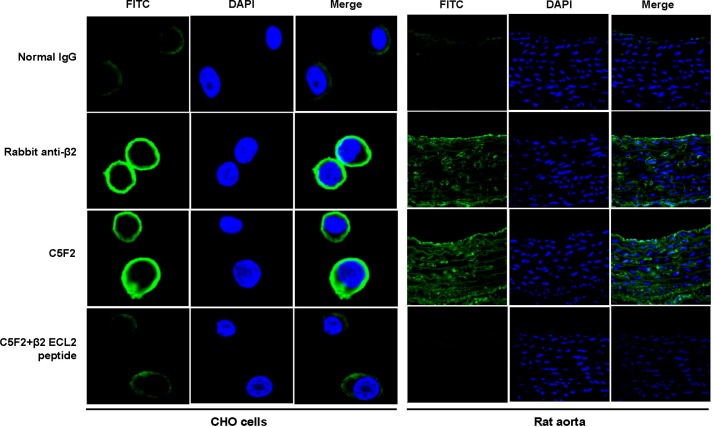

Western blotting with C5F2 or rabbit anti-β2AR polyclonal antibody as a positive control revealed an immunoreactive band of ∼65 kDa in the H9c2 cell lysate (Fig. 3), which corresponded to glycosylated β2AR (30). To check the specificity of reactivity, C5F2 was neutralized with the β2AR ECL2 peptide before immunodetection (Fig. 3). The intensity of the immunoreactive band was greatly decreased by peptide pre-absorption. To analyze binding of C5F2 to β2AR, immunofluorescence was also performed with rat aorta and CHO cells expressing human β2AR. C5F2 reacted with the receptor in both aorta tissue and CHO cells (Fig. 4). In rat aorta, C5F2 binding was observed in the endothelium, as well as in the medial smooth muscle cell. The staining pattern was similar to that obtained with rabbit anti-β2AR polyclonal antibody. Preincubation of C5F2 with the β2AR ECL2 peptide diminished the fluorescence signal in both aorta tissue and CHO cells, confirming the specific binding of C5F2 to β2AR. Pooled normal human IgG did not show any significant reactivity.

FIGURE 3.

Immunoblot reactivity of C5F2 with β2AR from H9c2 cardiomyocytes. A, representative immunoblot of β2AR. H9c2 cell lysate, loaded in duplicated lanes, was probed with C5F2 or rabbit anti-β2AR polyclonal antibody (positive control). GAPDH was used as an internal loading control. Both C5F2 and the positive control antibody reacted with 65-kDa β2AR. C5F2 specificity was confirmed by blocking with the β2AR ECL2 peptide. B, densitometric analysis of the immunoblot band for β2AR. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.01 versus C5F2 + β2 ECL2 peptide (n = 3).

FIGURE 4.

Immunofluorescence staining of β2AR with C5F2 in CHO cells and rat aorta. CHO cells expressing human β2AR and rat aorta tissue were stained with C5F2, rabbit anti-β2AR polyclonal antibody (positive control), or pooled normal human IgG (negative control) and FITC (green)-labeled secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Both C5F2 and the positive control antibody demonstrated strong reactivity, whereas normal control IgG did not show any significant binding. C5F2 binding was abolished by pre-absorption with the β2AR ECL2 peptide. All images were obtained at ×40 magnification.

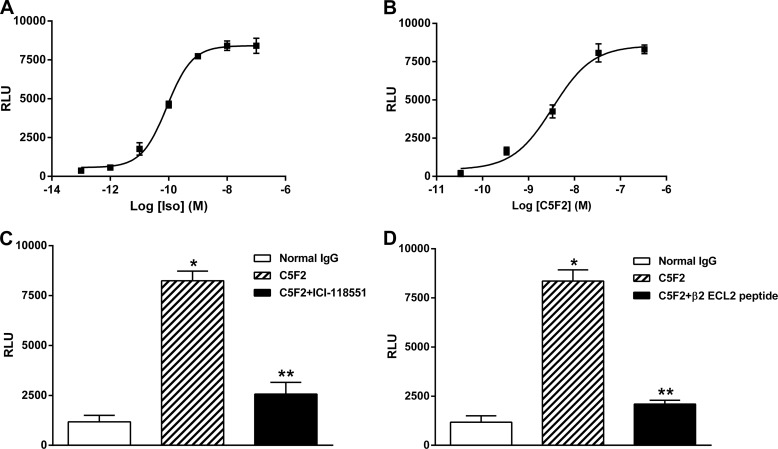

C5F2-stimulated cAMP Production

C5F2 was tested for its ability to stimulate cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human β2AR (Fig. 5). A typical dose response for the β-agonist control isoproterenol is shown in Fig. 5A. A similar dose effect for C5F2 was observed (Fig. 5B). C5F2 reached its maximal effect at ∼50 nm with an EC50 of 3 nm. C5F2 (50 nm) induced a significant increase in cAMP production compared with pooled normal human IgG (8352 ± 574 versus 1175 ± 324 relative luminescence units; p < 0.01), which was effectively blocked by the β2AR-specific blocker ICI-118551 (1 μm) (Fig. 5C) and by preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide (Fig. 5D) (2568 ± 581 and 2095 ± 199 relative luminescence units, respectively; p < 0.01). No significant increase in cAMP production was found with normal human IgG compared with the buffer base line.

FIGURE 5.

C5F2-induced cAMP production in CHO cells. β2AR-expressing CHO cells were treated with C5F2 or the β-agonist control isoproterenol (Iso). cAMP levels were measured using a luminescence assay. A, dose-response curve of isoproterenol. B, dose-response curve of C5F2. C5F2 stimulated cAMP production in a dose-dependent fashion similar to isoproterenol. Compared with normal human control IgG, C5F2 significantly increased cAMP production (*, p < 0.01; n = 3), whereas the β2AR-selective blocker ICI-118551 (C) or preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide (D) effectively blocked the C5F2-induced β2AR activation of cAMP production (**, p < 0.01; n = 3). Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. RLU, relative luminescence units.

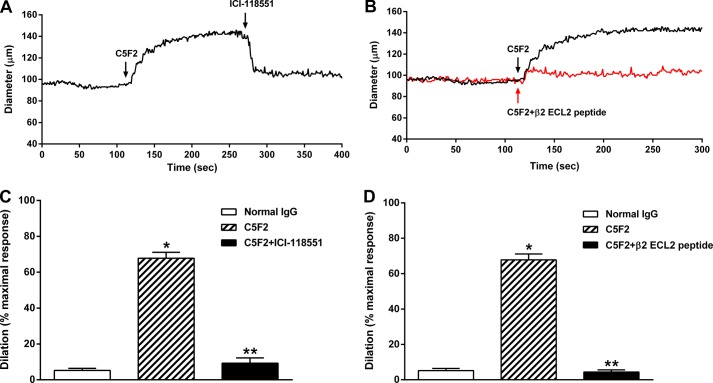

C5F2-induced Vasodilatation

The vasodilator response to C5F2 was examined using a rat cremaster arteriolar assay (Fig. 6). There was a significant dose effect on vasodilatation for C5F2 (data not shown). Representative tracings of C5F2-induced vasodilatation and its blockade by the β2AR-specific blocker ICI-118551 and by preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide are shown in Fig. 6 (A and B). C5F2 (100 nm)-induced vasodilatation was significantly decreased by ICI-118551 (1 μm) (Fig. 6C) and by preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide (Fig. 6D) (from 67.8 ± 5.8% to 9.3 ± 5.1% and 4.4 ± 2.1%, respectively; p < 0.01), indicating that antibody activation of vascular β2AR may contribute to systemic vasodilatation. Pooled normal human IgG failed to produce any significant vasodilatation.

FIGURE 6.

C5F2-induced resistance arteriolar dilation. The vasodilatory effect of C5F2 was examined using an isolated rat cremaster arteriole assay. Representative tracings of C5F2-induced vasodilatation and its blockade by the β2AR-selective blocker ICI-118551 (A) or preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide (B) are shown. Compared with normal human control IgG, C5F2 caused a significant dilation (*, p < 0.01; n = 3), which was almost completely blocked by ICI-118551 (C) or preincubation with the β2AR ECL2 peptide (D) (**, p < 0.01; n = 3). Data (mean ± S.D.) are expressed as a percentage of the maximal dilatory response, which was defined as the increase in diameter from basal tone to the maximal Ca2+-free passive dilation at 70 mm Hg measured at the end of each preparation.

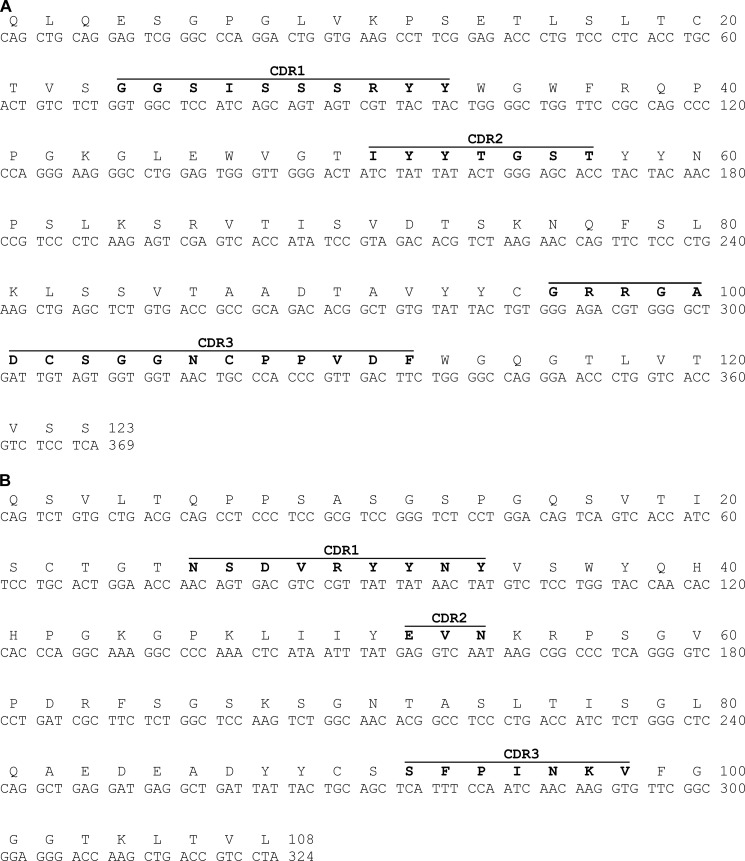

Sequence Analysis of C5F2 Variable Regions

The VH(D)J/VLJ genes of the C5F2 heavy chain and λ-light chain were cloned and sequenced. The nucleotide sequences of the C5F2 VH and VL genes, shown in Fig. 7 (A and B), were submitted to the IgBLAST and International Immunogenetics Information System (IMGT) databases for comparison with germ-line sequences. The germ-line genes most homologous to the C5F2 VH and VL genes are VH4-39 and VL2-8, respectively. The C5F2 VH gene has 97.3% homology to the germ-line VH4-39 gene, and the C5F2 VL gene has 93.8% homology to the germ-line VL2-8 gene.

FIGURE 7.

Nucleotide and translated amino acid sequences of the C5F2 heavy chain (A) and λ-light chain (B) variable regions. The sequences were analyzed using the IgBLAST and IMGT/V-QUEST tools. The CDRs are highlighted in boldface.

DISCUSSION

Isolating monoclonal autoantibodies from humans by cell fusion presents a considerable challenge due to the small number of antigen-specific activated B cells in circulation. The difficulty in obtaining functionally active monoclonal antibodies, e.g. thyroid-stimulating monoclonal antibodies, is well recognized (31). To date, only one human thyroid-stimulating monoclonal autoantibody has been isolated and characterized (32). Here, we have reported the successful cloning of an agonist-like anti-β2AR monoclonal antibody (C5F2) from a patient with idiopathic postural hypotension and recurrent cardiac tachyarrhythmias. This antibody recognized an epitope in the N-terminal sequence of β2AR ECL2, which may be critical for formation of the active receptor conformation. ECL2 appears to be a major autoimmune target, as most reported GPCR autoantibodies target this domain. Previous studies on the β1AR structure revealed that the only predicted amino acid stretch containing both B and T cell epitopes accessible to antibodies was located in ECL2 of β1AR (33). This may well be the case for other GPCRs.

A single-chain variable fragment derived from a mouse β2AR-activating monoclonal antibody (GenBankTM accession number AJ574851) has been reported previously (34). Although it is very difficult to compare the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of fully human and fully mouse antibodies, the mouse antibody heavy chain CDR3 is GGRGLDV, and our human heavy chain CDR3 is GRRGADCSGGNCPPVDF, indicating that perhaps the GXRGXD motif is important for binding to the receptor.

The mechanism by which autoantibodies activate β2AR is not yet clear. GPCR autoantibodies act as allosteric modulators of their target receptors, which may promote or stabilize receptor conformational changes required for receptor activation. It is known that GPCRs can exist as functional dimers (35); therefore, the bivalent autoantibodies may exert their agonistic effect by inducing and stabilizing an active dimeric receptor conformation. This concept was supported by the loss of activity from cleavage of an agonistic mouse anti-β2AR monoclonal antibody into monovalent Fab fragments and restoration after cross-linking of the fragments with anti-mouse IgG (36).

The monoclonal antibody C5F2 had a high binding affinity for the β2AR ECL2 peptide as measured by SPR. In addition, it reacted with differing tissues known to possess β2AR, including native β2AR, in H9c2 cardiomyocytes, CHO cells expressing human β2AR, rat aorta, and rat cremaster arterioles. Specific binding of C5F2 to β2AR was confirmed by inhibition with the β2AR ECL2 peptide. Functionally, C5F2 was able to stimulate cAMP production in β2AR-expressing CHO cells, which could be specifically blocked by a β2AR-selective antagonist and by the β2AR ECL2 peptide. More importantly, C5F2 perfusion of resistance arterioles produced a potent vasodilatation, which could also be inhibited by the β2AR blocker and β2AR ECL2 peptide, indicating that antibody activation of vascular β2AR may contribute to systemic vasodilatation. The functional activity of C5F2 was consistent with that of serum IgG polyclonal autoantibodies from the patient and of serum anti-β2AR autoantibodies harbored in a subgroup of postural hypotension patients (21, 22). β2AR-mediated vasodilatation in resistance arteries involves two different mechanisms: direct vasodilatation via activation of cAMP/PKA-mediated dephosphorylation of the smooth muscle myosin (37) and endothelial nitric oxide-mediated vasodilatation (38). The finding that β2AR-activating autoantibodies intrinsically possess the capability to induce significant systemic arteriolar vasodilatation suggests that these autoantibodies may contribute to postural hypotension by altering the normal autonomic response to upright posture.

Both β1AR and β2AR have a significant impact on cardiac function. The identification of a unique role for each in atrial and ventricular function has occupied a large number of investigators over the years since these receptors were identified. We recently reported that activation of β2AR following autoimmunization of a rabbit model with the β2AR ECL2 peptide was associated with development of sustained atrial tachyarrhythmias that were distinctly different from those observed in the β1AR-autoimmunized rabbit (16). It is possible that activating autoantibodies to β2AR and β1AR may induce cardiac tachyarrhythmias when other risk factors such as aberrant atrioventricular conduction and ischemia coexist.

The availability of this human monoclonal autoantibody has important implications for future studies on the precise mechanisms of antibody-mediated receptor activation. Detailed analysis of antibody-receptor interactions with powerful techniques such as x-ray crystallography can also be expected to lead to new interventions based on specific inhibition of pathological autoantibodies.

The effects of C5F2 on receptor binding of orthosteric ligands remain to be studied. The orthosteric ligand-binding sites on β2AR are located within a pocket formed by the first and second extracellular loops (39). Whether allosteric autoantibodies can alter orthosteric ligand binding will be determined by future competitive binding studies. Moreover, the allosteric modulation of orthosteric agonist-mediated signaling by autoantibodies and its implications in cardiovascular pathophysiology need to be explored. A single-chain variable fragment constructed from a mouse β2AR-activating monoclonal antibody has been shown to serve as an allosteric inverse agonist (34). Further studies on C5F2 using a similar approach will provide important data supporting development of novel and highly specific allosteric GPCR modulators.

In conclusion, an agonist-like human anti-β2AR monoclonal autoantibody was isolated and characterized. The specificity and functional properties of this antibody support the concept that circulating autoantibodies serve as vasodilators and may cause or exacerbate orthostasis by altering the compensatory postural vascular response. The known impact of β2AR agonists on cardiac function and the association of tachyarrhythmias in the patient harboring this autoantibody support a broad role of these autoantibodies in cardiovascular pathophysiology. The availability of this first human monoclonal autoantibody to β2AR provides opportunities to identify previously unrecognized causes and new pharmacological management of postural hypotension and other cardiovascular diseases.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL056267 and P30 GM103510. This work was also supported by a Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant, an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship, and individual grant support from Will and Helen Webster.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- ECL2

- second extracellular loop

- β2ΑR

- β2-adrenergic receptor

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- CDR

- complementarity-determining region.

REFERENCES

- 1. Magnusson Y., Wallukat G., Waagstein F., Hjalmarson A., Hoebeke J. (1994) Autoimmunity in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Characterization of antibodies against the β1-adrenoceptor with positive chronotropic effect. Circulation 89, 2760–2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jahns R., Boivin V., Siegmund C., Inselmann G., Lohse M. J., Boege F. (1999) Autoantibodies activating human β1-adrenergic receptors are associated with reduced cardiac function in chronic heart failure. Circulation 99, 649–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wallukat G., Fu H. M., Matsui S., Hjalmarson A., Fu M. L. (1999) Autoantibodies against M2 muscarinic receptors in patients with cardiomyopathy display non-desensitized agonist-like effects. Life Sci. 64, 465–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wallukat G., Morwinski M., Kowal K., Förster A., Boewer V., Wollenberger A. (1991) Autoantibodies against the β-adrenergic receptor in human myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: β-adrenergic agonism without desensitization. Eur. Heart J. 12, 178–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mascaro-Blanco A., Alvarez K., Yu X., Lindenfeld J., Olansky L., Lyons T., Duvall D., Heuser J. S., Gosmanova A., Rubenstein C. J., Cooper L. T., Kem D. C., Cunningham M. W. (2008) Consequences of unlocking the cardiac myosin molecule in human myocarditis and cardiomyopathies. Autoimmunity 41, 442–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fu M. L., Herlitz H., Wallukat G., Hilme E., Hedner T., Hoebeke J., Hjalmarson A. (1994) Functional autoimmune epitope on α1-adrenergic receptors in patients with malignant hypertension. Lancet 344, 1660–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luther H. P., Homuth V., Wallukat G. (1997) α1-Adrenergic receptor antibodies in patients with primary hypertension. Hypertension 29, 678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wenzel K., Haase H., Wallukat G., Derer W., Bartel S., Homuth V., Herse F., Hubner N., Schulz H., Janczikowski M., Lindschau C., Schroeder C., Verlohren S., Morano I., Muller D. N., Luft F. C., Dietz R., Dechend R., Karczewski P. (2008) Potential relevance of α1-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies in refractory hypertension. PLoS ONE 3, e3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chiale P. A., Ferrari I., Mahler E., Vallazza M. A., Elizari M. V., Rosenbaum M. B., Levin M. J. (2001) Differential profile and biochemical effects of antiautonomic membrane receptor antibodies in ventricular arrhythmias and sinus node dysfunction. Circulation 103, 1765–1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiale P. A., Garro H. A., Schmidberg J., Sánchez R. A., Acunzo R. S., Lago M., Levy G., Levin M. (2006) Inappropriate sinus tachycardia may be related to an immunologic disorder involving cardiac β-adrenergic receptors. Heart Rhythm 3, 1182–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baba A., Yoshikawa T., Fukuda Y., Sugiyama T., Shimada M., Akaishi M., Tsuchimoto K., Ogawa S., Fu M. (2004) Autoantibodies against M2-muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: new upstream targets in atrial fibrillation in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 25, 1108–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stavrakis S., Yu X., Patterson E., Huang S., Hamlett S. R., Chalmers L., Pappy R., Cunningham M. W., Morshed S. A., Davies T. F., Lazzara R., Kem D. C. (2009) Activating autoantibodies to the β1-adrenergic and M2 muscarinic receptors facilitate atrial fibrillation in patients with Graves' hyperthyroidism. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54, 1309–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wallukat G., Nissen E., Morwinski R., Müller J. (2000) Autoantibodies against the β and muscarinic receptors in cardiomyopathy. Herz 25, 261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dragun D., Philippe A., Catar R., Hegner B. (2009) Autoimmune mediated G-protein receptor activation in cardiovascular and renal pathologies. Thromb. Haemost. 101, 643–648 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jahns R., Boivin V., Hein L., Triebel S., Angermann C. E., Ertl G., Lohse M. J. (2004) Direct evidence for a β1-adrenergic receptor-directed autoimmune attack as a cause of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1419–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li H., Scherlag B. J., Kem D. C., Zillner C., Male S., Thirunavukkarasu S., Shen X., Pitha J. V., Cunningham M. W., Lazzara R., Yu X. (2013) Atrial tachycardia provoked in the presence of activating autoantibodies to β2-adrenergic receptor in the rabbit. Heart Rhythm 10, 436–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fu M. L., Schulze W., Wallukat G., Hjalmarson A., Hoebeke J. (1996) A synthetic peptide corresponding to the second extracellular loop of the human M2 acetylcholine receptor induces pharmacological and morphological changes in cardiomyocytes by active immunization after 6 months in rabbits. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 78, 203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matsui S., Fu M. L., Katsuda S., Hayase M., Yamaguchi N., Teraoka K., Kurihara T., Takekoshi N., Murakami E., Hoebeke J., Hjalmarson A. (1997) Peptides derived from cardiovascular G-protein-coupled receptors induce morphological cardiomyopathic changes in immunized rabbits. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 29, 641–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou Z., Liao Y. H., Wei Y., Wei F., Wang B., Li L., Wang M., Liu K. (2005) Cardiac remodeling after long-term stimulation by antibodies against the α1-adrenergic receptor in rats. Clin. Immunol. 114, 164–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wenzel K., Wallukat G., Qadri F., Hubner N., Schulz H., Hummel O., Herse F., Heuser A., Fischer R., Heidecke H., Luft F. C., Muller D. N., Dietz R., Dechend R. (2010) α1A-adrenergic receptor-directed autoimmunity induces left ventricular damage and diastolic dysfunction in rats. PLoS ONE 5, e9409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu X., Stavrakis S., Hill M. A., Huang S., Reim S., Li H., Khan M., Hamlett S., Cunningham M. W., Kem D. C. (2012) Autoantibody activation of β-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors contributes to an “autoimmune” orthostatic hypotension. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 6, 40–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li H., Kem D. C., Reim S., Khan M., Vanderlinde-Wood M., Zillner C., Collier D., Liles C., Hill M. A., Cunningham M. W., Aston C. E., Yu X. (2012) Agonistic autoantibodies as vasodilators in orthostatic hypotension: a new mechanism. Hypertension 59, 402–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adderson E. E., Shikhman A. R., Ward K. E., Cunningham M. W. (1998) Molecular analysis of polyreactive monoclonal antibodies from rheumatic carditis: human anti-N-acetylglucosamine/anti-myosin antibody V region genes. J. Immunol. 161, 2020–2031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hill M. A., Zou H., Davis M. J., Potocnik S. J., Price S. (2000) Transient increases in diameter and [Ca2+]i are not obligatory for myogenic constriction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, H345–H352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith K., Garman L., Wrammert J., Zheng N. Y., Capra J. D., Ahmed R., Wilson P. C. (2009) Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen. Nat. Protoc. 4, 372–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ye J., Ma N., Madden T. L., Ostell J. M. (2013) IgBLAST: an immunoglobulin variable domain sequence analysis tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W34–W40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giudicelli V., Chaume D., Lefranc M. P. (2004) IMGT/V-QUEST, an integrated software program for immunoglobulin and T cell receptor V-J and V-D-J rearrangement analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W435–W440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brochet X., Lefranc M. P., Giudicelli V. (2008) IMGT/V-QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W503–W508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lebesgue D., Wallukat G., Mijares A., Granier C., Argibay J., Hoebeke J. (1998) An agonist-like monoclonal antibody against the human β2-adrenoceptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 348, 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benovic J. L., Shorr R. G., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1984) The mammalian β2-adrenergic receptor: purification and characterization. Biochemistry 23, 4510–4518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McLachlan S. M., Rapoport B. (2004) Thyroid stimulating monoclonal antibodies: overcoming the road blocks and the way forward. Clin. Endocrinol. 61, 10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanders J., Evans M., Premawardhana L. D., Depraetere H., Jeffreys J., Richards T., Furmaniak J., Rees Smith B. (2003) Human monoclonal thyroid stimulating autoantibody. Lancet 362, 126–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoebeke J. (1996) Structural basis of autoimmunity against G protein coupled membrane receptors. Int. J. Cardiol. 54, 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peter J. C., Eftekhari P., Billiald P., Wallukat G., Hoebeke J. (2003) scFv single chain antibody variable fragment as inverse agonist of the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36740–36747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Milligan G. (2004) G protein-coupled receptor dimerization: function and ligand pharmacology. Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mijares A., Lebesgue D., Wallukat G., Hoebeke J. (2000) From agonist to antagonist: Fab fragments of an agonist-like monoclonal anti-β2-adrenoceptor antibody behave as antagonists. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murray K. J. (1990) Cyclic AMP and mechanisms of vasodilation. Pharmacol. Ther. 47, 329–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Queen L. R., Ferro A. (2006) β-Adrenergic receptors and nitric oxide generation in the cardiovascular system. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1070–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noda K., Saad Y., Graham R. M., Karnik S. S. (1994) The high affinity state of the β2-adrenergic receptor requires unique interaction between conserved and non-conserved extracellular loop cysteines. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6743–6752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]