Background: The EGF receptor, ErbB2, and ErbB3 can interact to form dimers.

Results: Analyses of these interactions show that ErbB3 interacts strongly with ErbB2 but weakly with the EGF receptor. All ErbB receptor interactions are enhanced by erlotinib and lapatinib.

Conclusion: ErbB3 binds and is functionally affected by tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Significance: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors restructure the network of ErbB interactions.

Keywords: Cancer Biology, Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), Growth Factors, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, ErbB2, ErbB3

Abstract

ErbB3 is a member of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases. It is unique because it is the only member of the family whose kinase domain is defective. As a result, it is obliged to form heterodimers with other ErbB receptors to signal. In this study, we characterized the interaction of ErbB3 with the EGF receptor and ErbB2 and assessed the effects of Food and Drug Administration-approved therapeutic agents on these interactions. Our findings support the concept that ErbB3 exists in preformed clusters that can be dissociated by NRG-1β and that it interacts with other ErbB receptors in a distinctly hierarchical fashion. Our study also shows that all pairings of the EGF receptor, ErbB2, and ErbB3 form ligand-independent dimers/oligomers. The small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors erlotinib and lapatinib differentially enhance the dimerization of the various ErbB receptor pairings, with the EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimer being particularly sensitive to the effects of erlotinib. The data suggest that the physiological effects of these drugs may involve not only inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity but also a dynamic restructuring of the entire network of receptors.

Introduction

The ErbB family consists of four homologous receptor tyrosine kinases: the EGF receptor, ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 (1). All of these receptors possess the standard structure for a receptor tyrosine kinase: an extracellular ligand binding domain, a single-pass transmembrane domain, an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, and a C-terminal tail harboring phosphorylatable tyrosine residues. With the exception of ErbB2, which has no known ligand, these receptors bind a homologous family of growth factors (2).

In the traditional model for receptor activation, the receptors exist in the membrane as monomers. Upon ligand binding, the receptor undergoes an extensive conformational change that allows the formation of back-to-back dimers by the extracellular domains of the receptors (3–5). Essentially all possible heterocombinations of ErbB family members can form. However, the ligandless ErbB2 appears to be the universally preferred dimerization partner (6–8). In addition, the EGF receptor and ErbB4 form homodimers. Dimerization of the extracellular domain permits the formation of activating asymmetric dimers of the intracellular kinase domains (9–11). In this asymmetric dimer, the activity of one kinase domain is stimulated, and it phosphorylates tyrosines on the C-terminal tail of its partner subunit. These tyrosines then serve as binding sites for the recruitment of SH2 and PTB domain-containing proteins that activate signaling pathways downstream of the receptor (12).

Within the ErbB family, ErbB3 is unique in that its tyrosine kinase domain is largely inactive (13, 14). As a result, ErbB3 must heterodimerize with a kinase-active partner to transduce a signal. ErbB2 appears to be the preferred dimerization partner for ErbB3 (8). In the ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer, both ErbB2 and ErbB3 become phosphorylated (8). As the phosphorylation occurs in trans, it is clear that the kinase-active ErbB2 could phosphorylate the C-terminal tail of ErbB3. However, it is difficult to explain how ErbB2 could be phosphorylated by the kinase-inactive ErbB3 in the context of an ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer. Indeed, recent work by Zhang et al. (15) has suggested that the phosphorylation of ErbB2 occurs within ErbB2/ErbB3 tetramers in which the active ErbB2 from one dimer phosphorylates the ErbB2 in the other dimer. Thus, signaling by ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimers necessitates the formation of higher-order receptor oligomers not required by other ErbB pairings.

In previous work we have used luciferase fragment complementation imaging to characterize the interaction of the EGF receptor with itself (16, 17) as well as with ErbB2 (18, 19). In this work, we extended these studies to include a characterization of dimers containing ErbB3. We also investigated the effect of ErbB-targeted drugs on these ErbB receptor dimers. Our data demonstrate that ErbB3 interacts with itself as well as with the EGF receptor and ErbB2. These interactions are differentially affected by EGF and NRG-1β as well as the ErbB-targeted therapeutics. Although catalytically impaired, ErbB3 binds both erlotinib and lapatinib, and this alters its ability to interact with other ErbB receptors. These data clarify the hierarchy of interactions among the ErbB receptors and suggest that small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors likely alter the dynamic equilibrium between ErbB3 and other ErbB family members.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

EGF was purchased from Biomedical Technologies. NRG-1β was purchased from R&D Systems. Antibodies to the EGFR, EGFR pTyr-1068, ErbB2 pTyr-1221/1222, and ErbB3 pTyr-1289 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against ErbB2 and ErbB3 were purchased from Millipore. Cetuximab was obtained from the Barnes Hospital pharmacy. Trastuzumab (HerceptinTM) and pertuzumab (PerjetaTM) were provided by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). Erlotinib was from Axon Medchem. Lapatinib was chemically synthesized and was a gift from Ron Bose (Washington University). A30 was generated enzymatically and purified as described previously (20). FetalPlex was from Gemini Bio-Products. ErbB3 in pcDNA3.1+ was a gift from Mark Lemmon (University of Pennsylvania).

DNA Constructs

The EGF receptor and ErbB2 fused to a flexible linker and either the N-terminal fragment of luciferase (NLuc) or the C-terminal fragment of luciferase (CLuc) in pBI-Tet or pcDNA3.1 were generated as described previously (18). In these constructs, the ErbB receptor can be removed by digestion with NheI and BsiWI. This leaves the BsiWI-to-NheI vector fragment with the flexible linker plus the luciferase fragment. The ErbB3-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc constructs were generated by introducing an upstream NheI site via QuikChange mutagenesis into ErbB3 in pcDNA3.1+. A BsiWI site was then engineered at the C terminus of ErbB3, removing the stop codon. The resulting ErbB3 insert was then isolated by digestion with NheI and BsiWI and ligated with the BsiWI-to-NheI vector portion of pBI-Tet or pcDNA3.1 containing the NLuc or CLuc fragment.

Cell Lines

A stable line of CHO cells expressing EGFR-NLuc on a Tet-inducible plasmid was transfected with ErbB3-CLuc in pcDNA3.1-Zeo. EGFR-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc clones were selected by growth in 500 μg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen). Similarly, a stable line of CHO cells expressing Tet-inducible ErbB2-NLuc was transfected with ErbB3-CLuc in pcDNA3.1Zeo. ErbB2-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc clones were selected by growth in 500 μg/ml zeocin. A double-stable line of CHO cells expressing ErbB3-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc was isolated by first transfecting parental Tet-on CHO cells with ErbB3-NLuc in pBI-Tet plus pTK-Hyg and selecting stable clones by growth in 500 μg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen). A single stable ErbB3-NLuc line was then transfected with ErbB3-CLuc in pcDNA3.1Zeo, and ErbB3-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc clones were selected by growth in 500 μg/ml zeocin.

Luciferase Assays

Cells were plated into 96-well black-walled dishes 48 h prior to use and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FetalPlex and the desired concentration of doxycycline (Clontech). Immediately prior to the assay, cells were transferred into Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium without phenol red with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) and incubated with 0.6 mg/ml D-luciferin for 20 min at 37 °C. Growth factor was then added at the indicated concentration, and cell radiance (photons/sec/cm2/steradian) was measured at 30-s intervals over a 25-min time course using a cooled charge-coupled device camera and imaging system (IVIS 50). For experiments involving the use of the A30 aptamer, assays were performed at 30 °C instead of 37 °C. Assays were performed in quintuplicate, and the data were analyzed as described previously (16).

Receptor Phosphorylation

Cells stably expressing the various pairs of ErbB receptors were grown to confluence in 35-mm dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FetalPlex and, when needed, 1 μg/ml doxycycline. For pretreatments with cetuximab, trastuzumab, or pertuzumab, cultures were incubated with 5 μg/ml antibody for 20 min at 37 °C prior to the assay. For pretreatment with erlotinib or lapatinib, cultures were incubated with 5 μm drug for 1 h at 37 °C. Immediately prior to the assay, cells were switched into Ham's F12 medium containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) plus the same concentration of antibody or kinase inhibitor present in the preincubation. EGF or NRG-1β were then added at the indicated concentration, and the incubation continued for 2 min at 37 °C. At the end of the incubation, the medium was removed, and cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were scraped into 0.4 ml radioimmune precipitation assay buffer and homogenized by passing through a 25-gauge needle. After pelleting insoluble material, equal amounts of protein were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 10% powdered milk and probed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

RESULTS

Luciferase Complementation in Pairings Containing ErbB3

Firefly luciferase can be separated into an N-terminal and a C-terminal fragment. The isolated fragments are enzymatically inactive. However, when brought into proximity, the two fragments can complement each other, reconstituting luciferase activity (21). The NLuc and CLuc fragments were each fused to the C terminus of ErbB3 and stably transfected into CHO cells. The ErbB3-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc cells were then assayed for the effect of increasing doses of NRG-1β on luciferase activity. The results are shown in Fig. 1A. For simplicity, ErbB3 is labeled as B3 in all figures, and ErbB2 is labeled as B2. The EGF receptor is labeled as B1.

FIGURE 1.

Luciferase complementation in ErbB3/ErbB3 and ErbB2/ErbB3 pairings. CHO cells stably coexpressing the indicated pairings were stimulated with increasing doses of NRG-1β, and luciferase complementation was measured as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” A, CHO cells coexpressing ErbB3-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc. B, CHO cells expressing ErbB2-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc. C, CHO cells expressing ErbB3-NLuc and ErbB3 CLuc were stimulated with 10 nm NRG-1β in the absence of addition (Control), or in the presence of 300 nm tRNA or 300 nm A30 aptamer. D, CHO cells expressing ErbB2-NLuc and ErbB3 CLuc were stimulated with 10 nm NRG-1β in the absence of addition (Control), or in the presence of 300 nm tRNA or 300 nm A30 aptamer. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

Addition of NRG-1β to the ErbB3-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc cells led to a dose-dependent decrease in luciferase activity. It is possible that hormone binding pushes ErbB3 into a conformation that impedes complementation, leading to the loss of signal. However, the data are entirely consistent with previous work that suggests that, under basal conditions, ErbB3 self-associates in cells and that binding of NRG-1β leads to the disaggregation of these clusters (22–24). The data could be well fit to single exponential decay curves. When the rate constants from the fitted curves were plotted against the concentration of NRG-1β, an EC50 of 35 pm was determined (not shown).

To characterize the interaction of ErbB3 with ErbB2, CHO cells were stably transfected with ErbB2-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc. As shown in Fig. 1B, treatment of these cells with NRG-1β resulted in a dose-dependent increase in luciferase complementation, indicating that NRG-1β promotes the interaction of ErbB3 with ErbB2. The data were fit to an exponential association model, and the fitted rate constants were plotted against the concentration of NRG-1β. This analysis yielded an EC50 of 380 pm for NRG-1β (not shown).

It has been shown recently that dimers of ErbB2 and ErbB3 are capable of forming tetramers (15). This occurs via an interface that is distinct from that used for the formation of the standard back-to-back dimers and appears to include portions of subdomain III of the extracellular domain. Zhang et al. (15) showed that an aptamer known as A30 inhibited tetramer formation without disrupting back-to-back dimer formation.

To determine whether our luciferase assay detected ErbB2/ErbB3 tetramers, the assays were repeated in the absence or presence of 300 nm A30. An equimolar concentration of tRNA was utilized as a negative control. The data in Fig. 1D demonstrate that the A30 aptamer partially inhibited NRG-1β-induced complementation in cells expressing ErbB2-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc. This is consistent with the presence of ErbB2/ErbB3 tetramers in this system and suggests that complementation can occur both within ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimers and across ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimers in the tetrameric complex. The A30 aptamer did not alter the ability of NRG-1β to reduce ErbB3/ErbB3 complementation (Fig. 1C), indicating that the effect of A30 is specific for the ErbB2/ErbB3 pairing.

ErbB3-CLuc was next coexpressed in CHO cells with EGFR-NLuc (referred to in the figures as B1). This pairing is unusual in that it can respond to either of two ligands: NRG-1β, which binds only to ErbB3, and EGF, which binds only to the EGF receptor. The data in Fig. 2 demonstrate that the EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimer responds differently to these two ligands. Treatment of the EGFR-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc cells with NRG-1β resulted in a small decrease in luciferase activity at the lowest doses of NRG-1β but a distinct increase in luciferase complementation at higher doses of the agonist (Fig. 2A). At the highest dose of NRG-1β, complementation declined somewhat, indicating a biphasic dose-response curve to NRG-1β. On the basis of these data, an estimate of ∼2–3 nm can be obtained for the EC50 for NRG-1β stimulation of EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimerization.

FIGURE 2.

Luciferase complementation in EGFR/ErbB3 pairings. CHO cells stably coexpressing EGFR-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc were stimulated with increasing doses of NRG-1β (A) or EGF (B), and luciferase complementation was measured as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” C, luciferase complementation in cells expressing EGFR-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc stimulated with 10 nm EGF alone (red), 10 nm NRG-1β alone (green), or 10 nm EGF + 10 nm NRG-1β (black). D, luciferase complementation in cells expressing EGFR-NLuc and EGFR-CLuc transfected with an empty vector or untagged wild-type EGFR, Y246D-EGFR, or WT-ErbB3. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

When EGFR-NLuc/ErbB3-CLuc cells were stimulated with EGF, there was a dose-dependent decrease in luciferase activity (Fig. 2B). The curves could be fit to a single exponential decay model. Plotting the fitted rate constants against the concentration of EGF yielded a value of ∼2 nm for the EGF-stimulated decrease in EGFR/ErbB3 dimers. This is similar to the EC50 for EGF for inducing homodimerization of its own receptor (16). The ability of EGF to induce dissociation of EGFR/ErbB3 predimers dominated the ability of NRG-1β to promote the formation of heterodimers between these two subunits. As can be seen in Fig. 2C, when saturating concentrations of EGF and NRG-1β were simultaneously applied to the cells, the net effect was essentially the same as when only EGF was added.

The ability of EGF to decrease the basal level of complementation between the EGF receptor and ErbB3 suggests the presence of preformed dimers of the EGF receptor and ErbB3 that either undergo a conformational change that reduces complementation or that are dissociated upon addition of EGF. The latter explanation seems most likely because the addition of EGF will clearly induce the formation of EGF receptor homodimers that would draw EGFR-NLuc subunits out of the pool available to interact with ErbB3-CLuc. To test this hypothesis, the effect of ErbB3 on the formation of EGF receptor homodimers was examined.

In the experiment shown in Fig. 2D, EGFR-NLuc was coexpressed with EGFR-CLuc in a double-stable cell line. As we have reported previously, treatment of cells expressing EGFR-NLuc/EGFR-CLuc with EGF leads to biphasic changes in luciferase activity (16–18). Initially, there is a rapid decline in luciferase complementation. This is followed by a recovery of luciferase activity back toward base-line values. This pattern is seen in both EGFR homodimers and EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers (18, 19). We have interpreted these data (16, 18, 19) as resulting from the presence of EGF receptor predimers (25–29) that give rise to a basal level of luciferase complementation. These predimers undergo a conformational change that reduces the efficiency of their complementation, thereby reducing the signal. The recovery of luciferase activity is due to the slower dimerization of EGF receptor monomers.

These EGFR-NLuc/EGFR-CLuc cells were transfected with an empty vector or with a vector encoding the wild-type EGF receptor, Y246D-EGF receptor, or wild-type ErbB3 that were not fused to luciferase. Tyrosine 246 is in the dimerization arm of the EGF receptor, and its mutation to Asp ablates the ability of the EGF receptor to undergo ligand-induced dimerization (3, 4, 30). These transfected receptors would be expected to compete with the EGF receptors that contain luciferase fragments and reduce the resulting complementation. Transfection with each of these receptors reduced basal luciferase complementation (not shown), consistent with their ability to compete with the tagged EGF receptors for the formation of predimers. In cells transfected with the wild-type EGF receptor, the addition of EGF resulted in the expected initial decline in luciferase activity as the predimers that had formed were reorganized. However, there was no recovery of luciferase. This is because the untagged EGF receptors competed to form dimers with the EGFR-NLuc or EGFR-CLuc receptors and, thus, blocked complementation. Although expression of the Y246D-EGF receptor reduced basal complementation, it had no effect on the biphasic pattern of EGF-stimulated luciferase activity. This is consistent with the fact that the Y246D-EGF receptor cannot form ligand-induced dimers and would thus be unable to compete effectively for the formation of EGFR-NLuc/EGFR-CLuc dimers in the recovery phase of the response. Like the Y246D-EGF receptor, wild-type ErbB3 did not compete effectively for the formation of EGF receptor homodimers, suggesting that it has a very weak affinity for the EGF receptor. These data indicate that, in the presence of EGF, the EGF receptor strongly prefers to homodimerize even if ErbB3 is available as an alternative dimerization partner.

Effect of ErbB-targeted Therapeutics on Phosphorylation of ErbB Receptors

Several ErbB-targeted agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in treating a variety of cancers. These include both monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Erlotinib and lapatinib are small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors that are ATP mimetics. Erlotinib shows selectivity for the EGF receptor over ErbB2 but, at high concentrations, inhibits both kinases (31). It appears to preferentially bind to the active form of the kinase domain (32) that is capable of forming the asymmetric dimer. Lapatinib is equally effective against the EGF receptor and ErbB2 and appears to preferentially target the inactive conformation of the kinase domain (31) that cannot form asymmetric dimers but may instead form symmetric head-to-head dimers (33). Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the EGF receptor and blocks the binding of EGF (34). This prevents the activation of EGF-dependent signaling events (35). Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody against the extracellular domain of ErbB2 (36, 37). Its efficacy appears to be due to its ability to induce an antibody-dependent cytotoxic response that leads to the destruction of the ErbB2-expressing cells (38). Pertuzumab is another monoclonal antibody directed against the extracellular domain of ErbB2. It has been shown to bind directly to the dimerization arm of ErbB2 that is required for the formation of back-to-back dimers (39), thereby inhibiting ErbB2-mediated signaling events (40).

Because the luciferase complementation assays offer the opportunity to directly monitor interactions between specific ErbB family members, we used this assay to examine the effect of these Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs on the dynamics of receptor-receptor interactions. We first documented the effects of the five ErbB-targeted drugs on the kinase activity of the various ErbB homo- and heterodimers. Fig. 3 shows the effect of these agents on the phosphorylation of ErbB subunits in five different homo- or heterodimeric pairings of the EGF receptor, ErbB2, and ErbB3. A saturating dose of agonist was used for the experiments shown in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of ErbB kinase activity by monoclonal antibodies and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors. CHO cells stably expressing the indicated ErbB receptors were grown to confluence in 6-well dishes and then treated with erlotinib (Erl), lapatinib (Lap), cetuximab (Cetux), trastuzumab (Tras), or pertuzumab (Pert) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cell were then stimulated for 2 min with either 10 nm EGF (A, B, and C) or 10 nm NRG-1β (D, E, and F). Cell lysates were prepared, analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and visualized by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

Erlotinib and lapatinib, the small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, blocked growth factor-stimulated phosphorylation of ErbB receptors in all pairings tested. Thus, these compounds are effective inhibitors of all ErbB phosphorylation. Likewise, cetuximab, the anti-EGF receptor antibody, blocked EGF-stimulated phosphorylation in all cell lines expressing the EGF receptor. Pertuzumab, which blocks the formation of back-to-back dimers by ErbB2, did indeed block EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of ErbB2 in cells coexpressing the EGF receptor and ErbB2. However, it did not block phosphorylation of the EGF receptor in cells coexpressing the EGF receptor and ErbB2. This is because EGF receptor phosphorylation can occur in the context of EGF receptor homodimers, which are not targeted by pertuzumab. Pertuzumab also blocked the NRG-1β-stimulated phosphorylation of ErbB2 and ErbB3 in cells coexpressing these receptors but did not reduce basal phosphorylation of ErbB2. Such basal phosphorylation may arise from intracellular phosphorylation of ErbB2 during its transit to the membrane. Trastuzumab has typically not been found to inhibit ErbB2 phosphorylation (41), and this was observed here as well. These data demonstrate that, in our cell lines, these agents exhibit their known inhibitory specificities with respect to ErbB receptor phosphorylation.

Although the small molecule inhibitors effectively blocked ErbB receptor kinase activity, they significantly increased basal luciferase complementation. As shown in Fig. 4, erlotinib increased basal luciferase activity in all five of the ErbB pairings, having its greatest effect on the EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimer. Lapatinib also increased basal luciferase activity in all pairings, but the magnitude of the effect was always less than that seen with erlotinib. The effects of erlotinib and lapatinib on basal complementation required the presence of the kinase domain as neither inhibitor significantly altered the complementation of a C-terminally truncated EGF receptor homodimer that lacked the entire intracellular domain (Fig. 4, sixth set of bars). Likewise, the increases could not be attributed to an enhancement in the ability of the luciferase fragments to complement each other because neither inhibitor affected the complementation observed when cells expressing FKBP-CLuc/FRB-NLuc (21) were stimulated with rapamycin. These quinazoline-based inhibitors have been shown to induce dimerization of the EGF receptor kinase domain (26, 42–44). Thus, the effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on luciferase complementation in these ErbB receptor pairings appears to be due to a direct effect on the kinase domains of the receptors themselves. Because even the ErbB3/ErbB3 pairing showed an increase in luciferase complementation, these data suggest that the kinase-deficient ErbB3 does, in fact, bind these two ATP mimetics and that the binding is associated with a structural and/or functional change in the ErbB3 kinase domain.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on basal luciferase complementation. CHO cells stably coexpressing the indicated pairs of ErbB receptors fused to NLuc or CLuc were treated with 5 μm erlotinib or lapatinib for 60 min prior to the assay for luciferase activity. Basal activity was taken as the average activity over the standard 25-min assay. Fold stimulation was determined by dividing the value obtained after treatment with erlotinib or lapatinib by the value obtained in cells treated with vehicle only. Values shown represent mean ± S.D. from two to four separate experiments done in quintuplicate. FKBP, FK506 binding protein; FRB, FKBP-rapamycin binding domain.

We next tested the effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on growth factor-stimulated luciferase complementation. Fig. 5 shows the results of luciferase complementation experiments in which cells expressing just the EGF receptor (Fig. 5, A and B) or the EGF receptor and ErbB2 (C and D) were treated with erlotinib or lapatinib. Fig. 5, A and C, document the effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on basal complementation in these pairings, with erlotinib stimulating a significantly greater increase in basal complementation than lapatinib. The effects of EGF on erlotinib- and lapatinib-treated cells are shown in Fig. 5, B and D. In both EGFR/EGFR homodimers and EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers, lapatinib treatment converted the response to EGF from the biphasic “dip and recovery” pattern to a simple exponential rise in luciferase activity. This is similar to the pattern observed when kinase-dead versions of the EGF receptor and ErbB2 are utilized in this assay (18). Thus, this change likely reflects the inhibition of kinase activity and indicates that the initial dip following hormone binding is associated with protein phosphorylation. Surprisingly, EGF failed to stimulate a further increase in luciferase activity in cells treated with a high concentration of erlotinib (5 μm). Because a lower dose of erlotinib (0.5 μm) sufficient to completely inhibit EGF receptor autophosphorylation yields the same pattern as lapatinib (not shown), it seems likely that this high dose of erlotinib (5 μm) promotes maximal receptor predimerization and, hence, that EGF is unable to further enhance receptor-receptor interactions. These effects of erlotinib and lapatinib are consistent with the results of cross-linking studies that suggested that erlotinib, but not lapatinib, induced maximal dimerization of the EGF receptor in the absence of EGF (25, 45).

FIGURE 5.

The effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on luciferase complementation between the EGF receptor and ErbB2. CHO cells stably coexpressing EGFR-NLuc and EGFR-CLuc (A and B) or EGFR-CLuc and ErbB2-NLuc (C and D) were treated with 5 μm erlotinib or lapatinib for 60 min. Cultures were then treated with vehicle (A and C) or 10 nm EGF (B and D) and assayed for luciferase activity. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

As shown in Fig. 6A, both erlotinib and lapatinib enhanced basal complementation in the ErbB3/ErbB3 pairing, with erlotinib consistently producing a greater rise than lapatinib. Stimulation with NRG-1β induced a similar decrease in the extent of complementation in control, erlotinib-, and lapatinib-treated cells (Fig. 6B). However, the rate of decline was slower in the inhibitor-treated cells. The ability of erlotinib and lapatinib to affect both basal and NRG-1β-induced luciferase activity clearly indicates that the ErbB3 kinase domain can bind these inhibitors and that this binding alters the interactions of the ErbB3 subunits.

FIGURE 6.

The effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on luciferase complementation in ErbB3 homo-oligomers. CHO cells stably expressing ErbB3-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc were treated with 5 μm erlotinib or lapatinib for 60 min. Cultures were then treated with vehicle (A) or 10 nm NRG-1β (B) prior to assay for luciferase activity. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

The effects of erlotinib and lapatinib on the ErbB2/ErbB3 pairing are shown in Fig. 7A, with both basal and NRG stimulation shown on the same panel. As can be seen (from the open circles that denote the basal level of complementation), erlotinib and lapatinib both promoted a significant increase in ligand-independent luciferase activity. Despite the greater increase in basal complementation seen with erlotinib as compared with lapatinib, NRG-1β stimulated the same maximal response in the presence of either inhibitor.

FIGURE 7.

The effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on luciferase complementation in ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimers. A, CHO cells stably coexpressing ErbB2-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc were treated with 5 μm erlotinib (Erlot) or lapatinib (Lapat) for 60 min. Cultures were then treated with vehicle (○) or 10 nm NRG-1β (NRG) (●) prior to the assay for luciferase activity. Con, control. B, C, and D, after treating with vehicle, erlotinib, or lapatinib, cells were stimulated with 10 nm NRG-1β and assayed for luciferase activity in the absence (○) or presence (●) of 300 nm A30. For the results shown in B, C, and D, luciferase activity was normalized for each treatment group by dividing the absolute change in photon flux observed in the presence of NRG-1β by the absolute photon flux in the absence of NRG-1β. Assays were done in quintuplicate.

Although NRG-1β stimulated the same level of complementation in erlotinib- and lapatinib-treated cells, there was a difference in their effect on the ErbB2/ErbB3 pairing. As shown in Fig. 7B, in control cells, the A30 aptamer inhibited complementation by ∼30%. In erlotinib-treated cells (Fig. 7C), this was reduced slightly to ∼20%. By contrast, in lapatinib-treated cells (Fig. 7D), addition of A30 led to an ∼40% inhibition of complementation. If one assumes that the A30-resistant activity is due to intradimer complementation (which would not be affected by disruption of tetramers), this suggests that erlotinib promotes more intradimer complementation, whereas lapatinib supports more complementation across the tetramer.

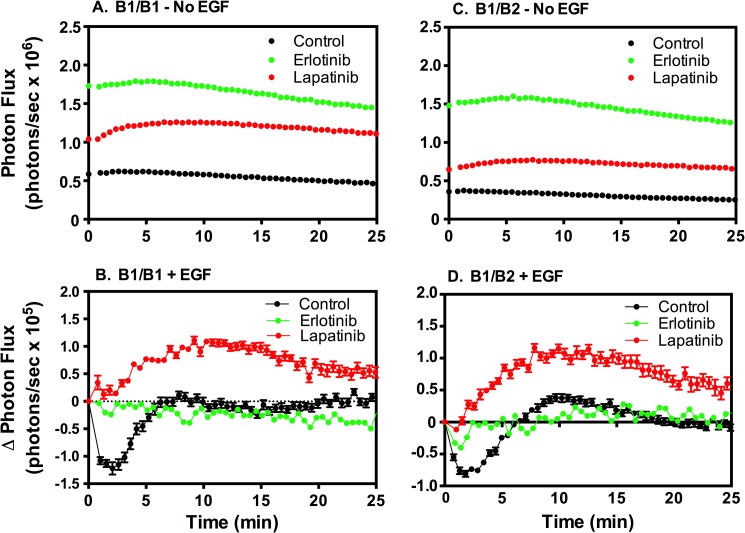

Fig. 8 shows the effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers. Both erlotinib and lapatinib stimulated an increase in basal complementation, but the effect of erlotinib was consistently substantially higher than the effect of lapatinib (Figs. 8, A and C). This suggests that these inhibitors promote the formation of EGFR/ErbB3 predimers. Stimulation of erlotinib-treated cells with NRG-1β led to a significant increase in luciferase activity that dwarfed the NRG-1β response in either control or lapatinib-treated cells (Fig. 8B). Thus, erlotinib clearly promoted or stabilized the formation of EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers in response to NRG-1β. Stimulation with EGF effectively reversed most of the erlotinib-induced increase in EGFR/ErbB3 predimers (Fig. 8D). As before, this probably reflects the preference of the EGF receptor to form homodimers, rather than EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers, in the presence of EGF.

FIGURE 8.

The effect of erlotinib and lapatinib on luciferase complementation between the EGF receptor and ErbB3. CHO cells stably coexpressing EGFR-NLuc and ErbB3-CLuc were treated with 5 μm erlotinib or lapatinib for 60 min. Cultures were then treated with vehicle (A and C), 10 nm NRG-1β (NRG) (B), or 10 nm EGF (D) and assayed for luciferase activity. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

ErbB-targeted Monoclonal Antibodies Selectively Inhibit Ligand-stimulated Dimerization of ErbB Receptors

Luciferase fragment complementation assays were also used to determine how cetuximab, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab affected interactions between the various ErbB family members. In contrast to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors, none of these antibodies altered basal luciferase complementation in any of the pairings (data not shown). Fig. 9 shows the effects of these antibodies on EGF-stimulated luciferase activity in EGFR/EGFR homodimers and EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers. As expected, cetuximab, which targets the EGF receptor, abolished the effect of EGF on luciferase complementation in both EGFR/EGFR homodimers (Fig. 9A) and EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers (B).

FIGURE 9.

The effect of monoclonal antibodies on complementation between the EGF receptor and ErbB2. CHO cells stably coexpressing EGFR-NLuc and EGFR-CLuc (A) or EGFR-CLuc and ErbB2-NLuc (B) were treated with vehicle or 5 μg/ml cetuximab (Cetux), trastuzumab (Trastuz), or pertuzumab (Pertuz) for 20 min prior to the addition of 10 nm EGF and assayed for luciferase activity. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

Consistent with the lack of effect of trastuzumab on receptor phosphorylation, incubation with the ErbB2-directed antibody, trastuzumab, did not affect the ability of EGF to modulate luciferase activity in EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers. By contrast, treatment with pertuzumab, the antibody that binds to the dimerization arm of ErbB2, significantly altered the response to EGF in cells expressing both the EGF receptor and ErbB2. As shown in Fig. 9B, pertuzumab treatment largely inhibited the recovery of luciferase activity after the initial decrease following hormone addition. This observation is consistent with the conclusion that this recovery phase is due to the continuing formation of back-to-back EGFR/ErbB2 dimers after the initial reorganization of the predimers.

None of the antibodies affected the ability of NRG-1β to dissociate oligomers of ErbB3 (Fig. 10A), which is expected because none of these antibodies directly target ErbB3. In cells expressing ErbB2 and ErbB3 (Fig. 10B), cetuximab, which is directed against the EGF receptor, had no effect on the ability of NRG-1β to induce dimerization of ErbB3 with ErbB2. Consistent with its lack of effect on NRG-1β-stimulated kinase activity in these cells (Fig. 3E), trastuzumab also did not affect the ability of NRG-1β to stimulate complementation between ErbB2 and ErbB3. By contrast, pertuzumab completely inhibited NRG-1β-stimulated dimerization of ErbB2 and ErbB3, consistent with its ability to block the formation of back-to-back dimers containing ErbB2.

FIGURE 10.

The effect of monoclonal antibodies on complementation in ErbB3-containing dimers. CHO cells stably coexpressing ErbB3-NLuc and ErbB3-Cluc (A), ErbB2-NLuc and ErbB3-Cluc (B), or EGFR-NLuc (B1) and ErbB3-CLuc (C and D) were treated with vehicle or 5 μg/ml cetuximab (Cetux), trastuzumab (Trastuz), or pertuzumab (Pertuz) for 20 min prior to growth factor stimulation and assayed for luciferase activity. Cells in A, B, and D were stimulated with 10 nm NRG-1β. Cells in C were stimulated with 10 nm EGF. Assays were done in quintuplicate, and values represent mean ± S.E.

In the EGFR/ErbB3 pairing, neither trastuzumab nor pertuzumab, the ErbB2-directed antibodies, had any effect on the ability of EGF (Fig. 10C) or NRG-1β (D) to alter interactions between the EGF receptor and ErbB3. However, cetuximab, which blocks the binding of EGF to its receptor, abrogated the ability of EGF to promote the loss of signal from EGFR/ErbB3 predimers. Interestingly, cetuximab also blocked the ability of NRG-1β to promote the dimerization of ErbB3 with the EGF receptor (Fig. 10D). This suggests that, in addition to blocking EGF binding, this antibody stabilizes a conformation of the EGF receptor extracellular domain that is unfavorable for its interaction with ligand-occupied ErbB3.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we directly monitor the interactions between the EGF receptor, ErbB2, and ErbB3 using luciferase fragment complementation imaging. This method provides a continuous readout of these interactions in intact cells in real time. As such, it is superior to complementation systems utilizing β-galactosidase that require cell lysis and subsequent enzymatic generation of a colored product to assess dimer formation at a single time point (46, 47). The luciferase system has allowed us to compare the behavior of five different ErbB receptor pairings. Our results suggest that ErbB3 interacts with itself, ErbB2, and the EGF receptor in a distinctly hierarchical fashion and that it binds to and is functionally altered by the small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors erlotinib and lapatinib.

In the ErbB3/ErbB3 pairing, NRG-1β induced a dose-dependent decrease in luciferase complementation, suggesting that this growth factor actually dissociates pre-existing clusters of ErbB3 receptors. This interpretation is consistent with the observations of Landgraf and co-workers (22–24), who previously demonstrated the presence of ligand-dissociable oligomers of the purified extracellular domain of ErbB3 as well as full-length ErbB3 in a live cell setting. A possible structural basis for the clustering of full-length ErbB3 was identified by Jura et al. (48), who reported that ErbB3 kinase domains formed head-to-head N-lobe dimers that could be tiled into clusters by interdimer interactions mediated by the C-terminal tails of the receptors. Presumably, agonist binding would weaken such interactions, facilitating the dissociation of non-functional ErbB3 clusters and allowing their productive interaction with other partners, such as ErbB2.

In the EGFR/ErbB3 and ErbB2/ErbB3 pairings, NRG-1β induced an increase in luciferase complementation, but the dose response to NRG-1β differed between the two pairings. The EC50 for NRG-1β was 380 pm for the ErbB2/ErbB3 pair but ∼2 nm for the EGFR/ErbB3 pair. This suggests that the former pairing is preferred over the latter pairing and is consistent with previous studies (6, 8). The ErbB3/ErbB3 clusters were actually dissociated by very low concentrations of NRG-1β, indicating that they are disfavored in the presence of ligand. Thus, our data suggest that the order of stability in NRG-1β-stimulated pairings is ErbB2/ErbB3 > EGFR/ErbB3 > ErbB3/ErbB3.

Although the ErbB3 ligand NRG-1β was able to promote the association of ErbB3 with the EGF receptor, the EGF receptor ligand, EGF, apparently did not. Addition of EGF to the EGFR/ErbB3 pairing led to a loss of signal rather than an increase in complementation. This remained true even in the presence of erlotinib, which strongly enhanced predimerization of the EGF receptor and ErbB3 as well as EGFR/ErbB3 dimerization stimulated by NRG-1β. Furthermore, untagged ErbB3 failed to compete with the luciferase-tagged EGF receptors in the complementation reaction, suggesting that it has a weak affinity for the EGF receptor in the presence of EGF. The simplest interpretation consistent with all the data is that addition of EGF induces the loss of signal from EGFR/ErbB3 predimers because homodimerization of the EGF receptor is greatly favored over heterodimerization with ErbB3. Our binding experiments suggest that the affinity of the EGF receptor for ErbB2 in the dimerization reaction is approximately the same as it is for another EGF receptor (19). Therefore, the order of stability for EGF-stimulated receptor pairings appears to be EGFR/EGFR ∼ EGFR/ErbB2 ≫ EGFR/ErbB3.

For all but one ErbB receptor pairing, we found direct evidence for the existence of predimers or clusters of the receptors. In EGF receptor homodimers and EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers, the addition of ligand resulted in an initial decline in luciferase complementation prior to the recovery of signal. This suggests that there had been some interaction between the two partners prior to the addition of ligand. Similarly, for the EGFR/ErbB3 pairing, the addition of EGF led to a loss of complementation, suggesting that these two receptors interact prior to ligand stimulation. Likewise, the ability of NRG-1β to induce the loss of signal from the ErbB3/ErbB3 pairing suggests the ligand-independent association of ErbB3 with itself. Although there is a basal signal in the ErbB2/ErbB3 pairing suggesting the possibility of predimers, we never observed a decrease in the basal complementation of this pair. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether specific predimers of these receptors exist. Because these two receptors appear to be spatially segregated (49), ErbB2/ErbB3 predimer formation may be quite low.

Addition of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors erlotinib and lapatinib increased basal luciferase activity in all pairings. Such quinazoline-based inhibitors have been shown to induce dimerization of the EGF receptor kinase domain (26, 42–44), suggesting that these inhibitor-induced interactions are likely mediated by the kinase domains of the receptors. Consistent with this conclusion, the effects of erlotinib and lapatinib were abrogated by removal of the kinase domain in the C-terminally truncated EGFR/EGFR pairing.

Given that the ATP binding site of ErbB3 is functionally compromised (13, 14), it was surprising to find that erlotinib and lapatinib increased basal luciferase complementation in ErbB3/ErbB3 clusters. However, this is consistent with reports that, although modified compared with other ErbB receptors, the ErbB3 kinase domain can still bind ATP (14, 48). It is interesting to note that erlotinib consistently induced a greater increase in basal luciferase activity in the ErbB3/ErbB3 pairing than did lapatinib. This suggests that this kinase-impaired receptor can distinguish between an inhibitor that preferentially binds to the active conformation of the kinase (erlotinib) and one that binds to the inactive conformation of the kinase (lapatinib).

Treatment of cells with erlotinib and lapatinib altered not only ligand-independent interactions between the ErbB receptors but also ligand-stimulated dimerization. In the case of the EGFR/EGFR and EGFR/ErbB2 pairings, treatment with erlotinib apparently induced maximal dimerization of the receptors because addition of EGF did not further increase luciferase complementation. Treatment of ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimers with either erlotinib or lapatinib led to a 5-fold greater level of NRG-1β-stimulated dimerization than was seen in untreated cells. And treatment of cells coexpressing the EGF receptor and ErbB3 led to a ∼70-fold increase in the formation of NRG-1β-induced EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers. This suggests that these inhibitors support the formation of more dimers than does the physiological nucleotide ATP and raises the possibility that ligand normally induces the dimerization of a relatively small fraction of the total pool of ErbB receptors at any given time. It is possible that the inhibitors stabilize otherwise transient dimers, leading to higher overall levels of dimerization. Because these compounds show differential effects on each of the ErbB receptor pairings, these drugs are likely to induce a redistribution of the subunits among the various dimers within the network even as they inhibit the activity of some nodes.

The EGF receptor and ErbB2-directed antibodies exhibited inhibitory effects consistent with their known specificity and prior characterization. Two observations are noteworthy, however. The first relates to the ability of cetuximab to inhibit the NRG-1β-stimulated heterodimerization of ErbB3 with the EGF receptor. This suggests that this antibody not only blocks the binding of EGF to its receptor but also alters its dimerization interface so that it becomes an even less favorable partner for ErbB3. Thus, part of the efficacy of this antibody may be due to its ability to allosterically impede dimerization of the EGF receptor with other ErbB receptors.

The second notable observation was the effect of pertuzumab on the EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimer. Although pertuzumab did not affect basal complementation or the initial EGF-stimulated dip in luciferase activity in this pairing, it did block the late recovery phase of luciferase activity. This demonstrates that this secondary rise in luciferase activity requires receptor dimerization and, as we have hypothesized previously (19), is therefore due to the formation of back-to-back dimers from receptor monomers.

CONCLUSIONS

These studies directly demonstrate that ErbB3 exists in oligomers or clusters that are dissociated by NRG-1β. They also show that ErbB3 interacts with both ErbB2 and the EGF receptor but that in both cases, NRG-1β may only drive a relatively small fraction of the ErbB3 to dimerize. The remainder of the subunits apparently exist as liganded monomers. These findings raise the possibility that ErbB3 is only a transient partner in receptor dimers/tetramers and, instead, functions largely as a scaffold for the assembly of signaling complexes. The data also document the ability of erlotinib and, to a lesser extent, lapatinib to induce ligand-independent interactions among all of the ErbB receptors. The ability of these ATP mimetics to alter both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent interactions among the various ErbB receptors suggests that the physiological effects of these drugs may involve not only inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity but also a dynamic restructuring of the entire network of receptors.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM082824 (to L. J. P.) and P50 CA94056 (to D. P. W.).

REFERENCES

- 1. Ferguson K. M. (2008) Structure-based view of epidermal growth factor receptor regulation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 37, 353–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wilson K. J., Gilmore J. L., Foley J., Lemmon M. A., Riese D. J., 2nd (2009) Functional selectivity of EGF family peptide growth factors: Implications for cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 122, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garrett T. P., McKern N. M., Lou M., Elleman T. C., Adams T. E., Lovrecz G. O., Zhu H.-J., Walker F., Frenkel M. J., Hoyne P. A., Jorissen R. N., Nice E. C., Burgess A. W., Ward C. W. (2002) Crystal Structure of a truncated epidermal growth factor receptor extracellular domain bound to transforming growth factor a. Cell 110, 763–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ogiso H., Ishitani R., Nureki O., Fukai S., Yamanaka M., Kim J.-H., Saito K., Sakamoto A., Inoue M., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S. (2002) Crystal structure of the complex of human epidermal growth factor and receptor extracellular domains. Cell 110, 775–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferguson K. M., Berger M. B., Mendrola J. M., Cho H.-S., Leahy D. J., Lemmon M. A. (2003) EGF Activates its receptor by removing interactions that autoinhibit ectodomain dimerization. Mol. Cell 11, 507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Graus-Porta D., Beerli R. R., Daly J. M., Hynes N. E. (1997) ErbB2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. EMBO J. 16, 1647–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karunagaran D., Tzahar E., Beerli R. R., Chen X., Graus-Porta D., Ratzkin B. J., Seger R., Hynes N. E., Yarden Y. (1996) ErbB-2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors. Implications for breast cancer. EMBO J. 15, 254–264 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tzahar E., Waterman H., Chen X., Levkowitz G., Karunagaran D., Lavi S., Ratzkin B. J., Yarden Y. (1996) A hierarchical network of interreceptor interactions determines signal transduction by neu differentiation factor/neuregulin and epidermal growth factor. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 5276–5287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang X., Gureasko J., Shen K., Cole P. A., Kuriyan J. (2006) An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell 125, 1137–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aertgeerts K., Skene R., Yano J., Sang B.-C., Zou H., Snell G., Jennings A., Iwamoto K., Habuka N., Hirokawa A., Ishikawa T., Tanaka T., Miki H., Ohta Y., Sogabe S. (2011) 1) Structural analysis of the mechanism of inhibition and allosteric activation of the kinase domain of HER2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 18756–18765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qiu C., Tarrant M. K., Choi S. H., Sathyamurthy A., Bose R., Banjade S., Pal A., Bornmann W. G., Lemmon M. A., Cole P. A., Leahy D. J. (2008) Mechanism of activation and inhibition of the HER4/ErbB4 kinase. Structure 16, 460–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Citri A., Yarden Y. (2006) EGF-ErbB signalling. Towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guy P. M., Platko J. V., Cantley L. C., Cerione R. A., Carraway K. L., 3rd (1994) Insect cell-expressed p180ErbB3 possesses an impaired tyrosine kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 8132–8136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi F., Telesco S. E., Liu Y., Radhakrishnan R., Lemmon M. A. (2010) ErbB3/HER3 intracellular domain is competent to bind ATP and catalyze autophosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7692–7697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Q., Park E., Kani K., Landgraf R. (2012) Functional isolation of activated and unilaterally phosphorylated heterodimers of ErbB2 and ErbB3 as scaffolds in Ligand-dependent signalling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 13237–13242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang K. S., Ilagan M. X., Piwnica-Worms D., Pike L. J. (2009) Luciferase fragment complementation imaging of conformational changes in the EGF receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7474–7482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang K. S., Macdonald-Obermann J. L., Piwnica-Worms D., Pike L. J. (2010) Asp-960/Glu-961 control the movement of the C-terminal tail of the EGF receptor to regulate asymmetric dimer formation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24014–24022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Macdonald-Obermann J. L., Piwnica-Worms D., Pike L. J. (2012) The mechanics of EGF receptor/ErbB2 kinase activation revealed by luciferase fragment complementation imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 137–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Y., Macdonald-Obermann J., Westfall C., Piwnica-Worms D., Pike L. J. (2012) Quantitation of the effect of ErbB2 on EGF receptor binding and dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 31116–31125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen C. H., Chernis G. A., Hoang V. Q., Landgraf R. (2003) Inhibition of heregulin signaling by an aptamer that preferentially binds to the oligomeric form of human epidermal growth factor receptor-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9226–9231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luker K. E., Smith M. C., Luker G. D., Gammon S. T., Piwnica-Worms H., Piwnica-Worms D. (2004) Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12288–12293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landgraf R., Eisenberg D. (2000) Heregulin reverses the oligomerization of HER3. Biochemistry 39, 8503–8511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park E., Baron R., Landgraf R. (2008) Higher-Order association states of cellular ErbB3 probed with photo-cross-linkable aptamers. Biochemistry 47, 11992–12005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kani K., Warren C. M., Kaddis C. S., Loo J. A., Landgraf R. (2005) Oligomers of ErbB3 have two distinct interfaces that differ in their sensitivity to disruption by heregulin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8238–8247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bublil E. M., Pines G., Patel G., Fruhwirth G., Ng T., Yarden Y. (2010) Kinase-mediated quasi-dimers of EGFR. FASEB J. 24, 4744–4755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chantry A. (1995) The kinase domain and membrane localization determine intracellular interactions between epidermal growth factor receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3068–3073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clayton A. H., Walker F., Orchard S. G., Henderson C., Fuchs D., Rothacker J., Nice E. C., Burgess A. W. (2005) Ligand-induced dimer-tetramer transition during the activation of cell surface epidermal growth factor receptor. A multidimensional microscopy analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30392–30399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martin-Fernandez M., Clarke D. T., Tobin M. J., Jones S. V., Jones G. R. (2002) Preformed oligomeric epidermal growth factor receptors undergo and ectodomain structure change during signaling. Biophys. J. 82, 2415–2427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu X., Sharma K. D., Takahashi T., Iwamoto R., Mekada E. (2002) Ligand-independent dimer formation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a step separable from ligand-induced EGFR signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2547–2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walker F., Orchard S. G., Jorissen R. N., Hall N. E., Zhang H.-H., Hoyne P. A., Adams T. E., Johns T. G., Ward C., Garrett T. P., Zhu H. J., Nerrie M., Scott A. M., Nice E. C., Burgess A. W. (2004) CR1/CR2 interactions modulate the functions of the cell surface epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22387–22398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wood E. R., Truesdale A. T., McDonald O. B., Yuan D., Hassell A., Dickerson S. H., Ellis B., Pennisi C., Horne E., Lackey K., Alligood K. J., Rusnak D. W., Gilmer T. M., Shewchuk L. (2004) A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (lapatinib). Relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off-rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 64, 6652–6659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stamos J., Sliwkowski M. X., Eigenbrot C. (2002) Structure of the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase domain alone and in complex with a 4-anilinoquinazoline inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46265–46272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jura N., Endres N. F., Engel K., Deindl S., Das R., Lamers M. H., Wemmer D. E., Zhang X., Kuriyan J. (2009) Mechanism for activation of the EGF receptor catalytic domain by the juxtamembrane segment. Cell 137, 1293–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li S., Schmitz K. R., Jeffrey P. D., Wiltzius J. J., Kussie P., Ferguson K. M. (2005) Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell 7, 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Graham J., Muhsin M., Kirkpatrick P. (2004) Cetuximab. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 549–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cho H.-S., Mason K., Ramyar K. X., Stanley A. M., Gabelli S. B., Denney D. W., Jr., Leahy D. J. (2003) Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the herceptin Fab. Nature 421, 756–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carter P., Fendly B. M., Lewis G. D., Sliwkowski M. X. (2000) Development of herceptin. Breast Dis. 11, 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clynes R. A., Towers T. L., Presta L. G., Ravetch J. V. (2000) Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat. Med. 6, 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Franklin M. C., Carey K. D., Vajdos F. F., Leahy D. J., de Vos A. M., Sliwkowski M. X. (2004) Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell 5, 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Agus D. B., Akita R. W., Fox W. D., Lewis G. D., Higgins B., Pisacane P. I., Lofgren J. A., Tindell C., Evans D. P., Maiese K., Scher H. I., Sliwkowski M. X. (2002) Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ritter C. A., Perez-Torres M., Rinehart C., Guix M., Dugger T., Engelman J. A., Arteaga C. L. (2007) Human breast cancer cells selected for resistance to trastuzumab in vivo overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB ligands and remain dependent on the ErbB receptor network. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 4909–4919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arteaga C. L., Ramsey T. T., Shawver L. K., Guyer C. A. (1997) Unliganded epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization induced by direct interaction of quinazolines with the ATP binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23247–23254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gan H. K., Walker F., Burgess A. W., Rigopoulos A., Scott A. M., Johns T. G. (2007) The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 increases the formation of inactive untethered EGFR dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2840–2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lichtner R. B., Menrad A., Sommer A., Klar U., Schneider M. R. (2001) Signaling-inactive epidermal growth factor receptor/ligand complexes in intact carcinoma cells by quinazoline tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 61, 5790–5795 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lu C., Mi L.-Z., Schürpf T., Walz T., Springer T. A. (2012) Mechanisms for kinase-mediated dimerization of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38244–38253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blakely B. T., Rossi F. M., Tillotson B., Palmer M., Estelles A., Blau H. M. (2000) Epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization monitored in live cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wehrman T. S., Raab W. J., Casipit C. L., Doyonnas R., Pomerantz J. H., Blau H. M. (2006) A system for quantifying dynamic protein interactions defines a role for herceptin in modulating ErbB2 interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19063–19068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jura N., Shan Y., Cao X., Shaw D. E., Kuriyan J. (2009) Structural analysis of the catalytically inactive kinase domain of the human EGF receptor 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21608–21613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang S., Raymond-Stintz M. A., Ying W., Zhang J., Lidke D. S., Steinberg S. L., Williams L., Oliver J. M., Wilson B. S. (2007) Mapping ErbB receptors on breast cancer cell membranes during signal transduction. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2763–2773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]