Abstract

Molecular mechanisms involved in uterine quiescence during gestation and those responsible for induction of labor at term are incompletely known. More than 10% of babies born worldwide are premature and 1,000,000 die annually. Preterm labor results in preterm delivery in 50% of cases in the United States explaining 75% of fetal morbidity and mortality. There is no Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment to prevent preterm delivery. Nitric oxide-mediated relaxation of human uterine smooth muscle is independent of global elevation of cGMP following activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. S-nitrosation is a likely mechanism to explain cGMP-independent relaxation to nitric oxide and may reveal S-nitrosated proteins as new therapeutic targets for the treatment of preterm labor. Employing S-nitrosoglutathione as an nitric oxide donor, we identified 110 proteins that are S-nitrosated in 1 or more states of human pregnancy. Using area under the curve of extracted ion chromatograms as well as normalized spectral counts to quantify relative expression levels for 62 of these proteins, we show that 26 proteins demonstrate statistically significant S-nitrosation differences in myometrium from spontaneously laboring preterm patients compared with nonlaboring patients. We identified proteins that were up-S-nitrosated as well as proteins that were down-S-nitrosated in preterm laboring tissues. Identification and relative quantification of the S-nitrosoproteome provide a fingerprint of proteins that can form the basis of hypothesis-directed efforts to understand the regulation of uterine contraction-relaxation and the development of new treatment for preterm labor.

Keywords: human pregnancy, labor, preterm labor, myometrium, smooth muscle, uterus, S-nitrosation, nitric oxide

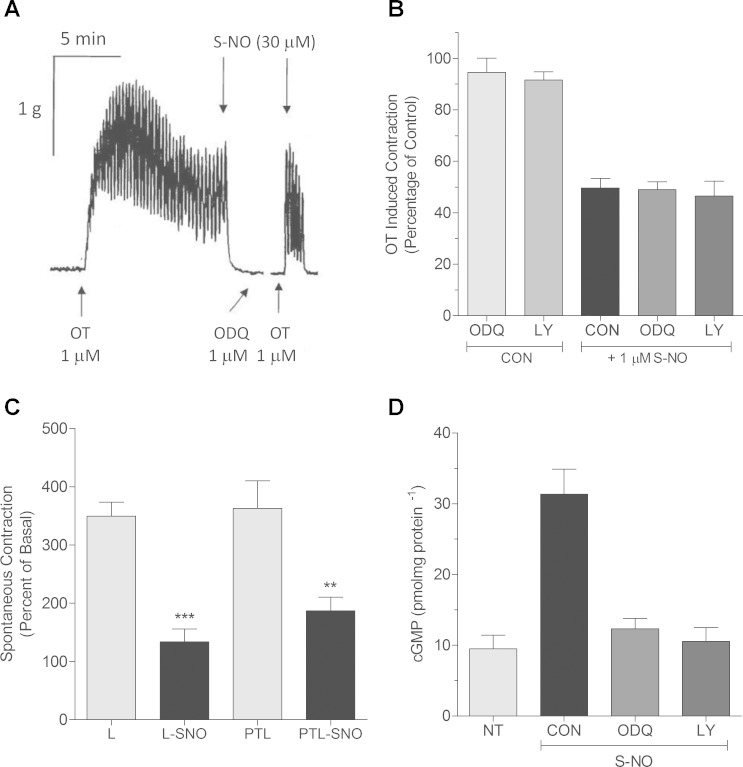

preterm labor affects one in eight pregnancies in the United States, leads to preterm delivery in >50% of cases, and this inexplicable tragedy (3, 4) in which 20,000 fetuses die annually disproportionally affects African American mothers (2). Over half of cases of preterm labor are spontaneous and unexplained. The molecular mechanisms involved in the induction of labor as well as preterm labor are incompletely known. Nitric oxide (NO) relaxes human uterine smooth muscle (HUSM) in a dose-dependent, global cyclic guanosine 3′-5′-monophosphate (cGMP)-independent manner (Fig. 1), while changes in cGMP associated with particulate guanylyl cyclase do relax myometrium (7, 13), and this may be gestationally regulated (13). In human myometrium, the non-cGMP-dependent actions of NO may reveal new therapeutic targets to prevent preterm labor (5).

Fig. 1.

Myometrial relaxation to nitric oxide is cGMP-independent. A: to measure agonist-mediated contraction/relaxation of pregnant myometrium, tissues were hung in organ baths and tension recorded as described in materials and methods. Addition (1:1,000) of the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor 1H-oxadiazoloquinoxalin-1-one (ODQ; 1 μM) was made 15 min before rechallenge with 1 μM oxytocin (OT). Break in the tracing represents 10-min rest and washout period subtracted from the record. In the presence of ODQ, relaxations to S-nitric oxide (NO) as cysteine-NO (Cys-NO) were unaffected. Recording is representative. B: addition of the guanylyl cyclase inhibitors ODQ (1 μM) or LY-83583 (10 μM) had no effect on OT-induced contractions (CON), while addition of Cys-NO (1 μM) caused significant relaxation regardless of pretreatment with the guanylyl cyclase inhibitors or not (CON). Data are means ± SE; n = 4–6. C: tissue strips from laboring (L) or preterm laboring (PTL) patients were hung in organ baths, and spontaneous contractions were relaxed by addition of 1 μM Cys-NO. Spontaneous contractions of both laboring human myometrium at term (***P < 0.001) and preterm laboring (<36 wk) tissues (**P < 0.01) were relaxed by S-NO treatment and were not different from one another. Data are mean ± SE; n = 6. D: OT-stimulated pregnant nonlaboring myometrial tissues were snap frozen under tension and basal cyclic GMP content (9 ± 2.1 pmol·mg−1·protein−1) determined by ELISA as described in materials and methods. OT stimulation (1 μM) had no effect on cyclic GMP content (NT; 9.5 ± 1.9 pmol·mg−1·protein−1), while Cys-NO stimulation (30 μM) led to a significant elevation in cyclic GMP (31.3 ± 3.6 pmol·mg−1·protein−1) that was blocked by prior treatment of tissues with guanylyl cyclase inhibitors ODQ (1 μM) or LY-83583 (10 μM). Data are means ± SE; n = 6.

NO may signal as an endogenous tocolytic in rodents (37, 41), but there is as yet no certainty that NO is present as an endogenous myometrial relaxing factor in women. What is clear is that NO relaxes human myometrium at concentrations (5) that could be present locally from uterine arterial endothelium or released from placental syncytiotrophoblasts (40) or macrophages (34, 44). The fact that NO signals nonclassically in human uterus and that it may selectively and disparately S-nitrosate proteins associated with pregnancy outcomes is compelling. If certain proteins contain a pregnancy-state-specific degree of S-nitrosation that is independent of the expression level for that protein, then we may learn more about both the function of S-nitrosated proteins and the basic regulation of uterine relaxation. Such S-nitrosated proteins and or their interactions with other proteins may be “druggable.” The importance of the fact that an effect of NO to relax the uterus is independent of global cGMP accumulation (Fig. 1) means that there can be discovery of therapeutic targets in the myometrium that are absent or disparately regulated in other smooth muscles and thus can permit a reasoned line of investigation to find uterine-specific tocolytics.

We propose that myometrial NO-mediated relaxation is dependent on S-nitrosation of specific and critical proteins involved in the relaxation of HUSM. We further hypothesize that these critical proteins are S-nitrosated disparately in pregnant laboring and preterm laboring HUSM compared with nonlaboring HUSM. S-nitrosation is a mechanistically important, NO-dependent, posttranslational modification that can alter smooth muscle relaxation/contraction dynamics (11).

Although many groups employ the term S-nitrosylation in place of S-nitrosation. Smith and Marletta (36) make a convincing argument that the nitroso group, not the nitrosyl group, is transferred during protein nitrosation reactions. We therefore have adopted this nomenclature to describe the conversion of a thiol to a nitrosothiol. S-nitrosation has been shown to alter the function of many proteins including the activity of several enzymes (18), and our previous work has shown disparate levels of S-nitrosation in guinea pig pregnancy (39). Based on the cGMP-independence of NO-mediated HUSM relaxation and prior research establishing that S-nitrosation is an established source of NO bioactivity, we propose that NO-mediated relaxation in HUSM is the result of protein-specific S-nitrosation. Moreover, whether or not it is NO that acts endogenously to mediate uterine quiescence during gestation, it is reasonable to determine the pregnancy state relaxation-associated S-nitrosation of proteins in myometrium on the basis that such efforts could identify targets mechanistically associated with uterine quiescence and thus can be useful in the effort to prevent preterm delivery. Here we present evidence of proteins that can be S-nitrosated by S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) as candidates belonging to contractile and inflammatory signaling pathways that can be examined in a hypothesis-directed fashion to find new therapeutic targets in the search for effective tocolytics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Sodium ascorbate, N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), neocuproine, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS), 3-(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and all other chemicals unless specified were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio) propionamide (biotin-HPDP) was from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL).

Tissue collection.

All research was reviewed and approved by the University of Nevada Biomedical Review Committee for the protection of human subjects. Human uterine myometrial biopsies were obtained with written informed consent from mothers undergoing elective Cesarean section in preterm labor without infection or rupture of membranes; term in labor or term not in labor. Tissues were transported to the laboratory immediately in cold physiological buffer, microdissected under magnification to isolate smooth muscle, employed in contractile experiments or snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The average age for patients in the pregnant laboring group was 28.9 ± 5.6 yr in the nonlaboring group 28 ± 5.1 yr and in the preterm laboring group 30.8 ± 10.2 yr. Pregnant laboring and nonlaboring patients ranged from 37 to 41 wk gestation, with the mean at 39 wk for both laboring and nonlaboring groups. Preterm laboring patients ranged from 29.2 to 36 wk of gestation, with the mean being 33.5 wk. Patients represented a range of ethnicities and were 52% Caucasian, 30% Hispanic, 7.4% African American, and 11% other.

Contractile studies.

Strips of myometrium (0.5 × 1 × 5 mm) were carefully cut from the center of the tissue section, mounted in organ baths (WPI, Sarasota, FL), and attached to isometric force transducers by silk thread. Transducer voltages were amplified and converted to digital signals by computer. Strips were maintained at 37°C, aerated with 100% O2, and loaded with initial tensions of 1.2 g mm3. During the course of a 1-h equilibration period, tissues were challenged twice with oxytocin (1 μM) followed by washout. All tissues employed in experiments were spontaneously active. NO was added to organ baths in the form of S-nitroso-l-cysteine (Cys-NO) from a fresh daily concentrated stock solution (14) for which water served as the solvent. Treatment of Cys-NO by bubbling the stock solution with oxygen for 30 min before use was employed as control. Such solutions were considered “spent” (25) and did not cause relaxation of the tissue. Addition of guanylyl cyclase inhibitors was made at baseline tension 15 min before addition of NO-donor. Tension was recorded in grams and presented as percentage above baseline tension.

Simultaneous measurement of tissue tension and cGMP content.

Spontaneously active tissue strips mounted within organ baths were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen spray at baseline, at peak tension following 1 μM oxytocin addition for nonlaboring tissues, or precisely 30 s after S-NO or control addition. Without allowing samples to thaw, tissues were homogenized with a Duall glass-glass homogenizer in 1 ml of 7% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) dissolved in acetone while constantly immersed in a methanol-dry ice slurry. Precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation, and TCA was removed by triplicate extraction with H2O-saturated diethyl ether and heating samples to 70°C for 10 min. After lyophilization, samples were resuspended in phosphate buffer and assayed for cyclic GMP by enzyme-linked immunoassay using antibodies obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Protein present in the acid precipitate was neutralized with NaOH and assayed by the bicinchoninic acid method. To inhibit GC activities, tissue strips mounted in organ baths were pretreated with 10 μM LY 83583 or 1 μM 1H-oxadiazoloquinoxalin-1-one (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) for 15 min at 37°C in the dark before the addition of Cys-NO. Guanylyl cyclase treatments were considered irreversible.

Protein isolation.

To isolate total protein, myometrial muscle samples from 12 patients in each pregnancy state were ground to a powder under liquid nitrogen and reconstituted in 20 ml HEN buffer (25 mM HEPES-NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM neocuproine, pH 7.7). Samples were sonicated (10 × 2-s bursts, 70% duty cycle) and brought to 0.4% CHAPS. Samples were then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay and samples diluted to 0.8 mg/ml in HEN buffer.

Biotin switch and streptavidin pull-down.

Samples from each patient in all groups was independently isolated by biotin switch and streptavidin pulldown and then pooled for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis (i.e., PTL1, 4 unique patients; PTL2, 4 unique patients; PTL3, 4 unique patients; for a total of 12 unique patients split into 3 biological replicates to help control for human diversity). Unless stated, all steps of the biotin switch were performed in the dark. Protein isolates (1.8 ml 0.8 mg/ml in HEN buffer) were incubated with GSNO (1,746 μl of sample + 54 μl of 10 mM GSNO prepared in the dark) for 20 min at room temperature. We selected a concentration for this labeling of 300 μM because at this concentration, GSNO will produce ∼5 μM reactive NO over 15–20 min without accumulation (10). This reactive species concentration matches the IC50 concentration for relaxation of isolated myometrium (5). Noncysteinyl nitrosation events would not be appreciated due to the reactive chemistry of ascorbate reduction; a nucleophilic attack at the nitroso-nitrogen atom leading to thiol and O-nitrosoascorbate (reaction 1)

which breaks down, by various competitive pathways, the dominant of which at physiological pH yields dehydroascorbic acid and nitroxyl radical that decomposes at physiological pH to nitrous oxide (24) (reaction 2).

Neither biotin-HPDP nor a maleimide dye would lead to false positives because the amines or tyrosines would not be labeled even if they were nitrosated. SDS (0.2 ml of 25% SDS in water) was added along with 20 μl of 3 M NEM (final 2.0 ml at 2.5% SDS and 30 mM NEM). Samples were incubated at 50°C in the dark for 20 min with frequent vortexing. Three volumes of cold acetone (6 ml) were added to each sample. Proteins were precipitated for 1 h at −20°C and collected by centrifugation at 3,000 g for 10 min. The clear supernatant was aspirated, and the protein pellet was gently washed with 70% acetone (4 × 5 ml). After resuspension in 0.24 ml HEN buffer with 1% SDS (HENS), the material was transferred to a fresh 1.7-ml microfuge tube containing 30 μl biotin-HPDP (2.5 mg/ml). The labeling reaction was initiated by addition 30 μl of 200 mM sodium ascorbate (final 20 mM ascorbate) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Four volumes of −20°C acetone were added to the labeled samples and incubated at −20°C for 20 min to remove biotin-HPDP. The samples were centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. The sides of the tube and the pellet were washed with −20°C acetone to remove traces of biotin-HPDP. The pellet was resuspended in 140 μl of HENS buffer. Neutralization buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.7, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100) was added (280 μl) along with 42 μl of streptavidin-agarose. Proteins were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed five times with 1.5 ml of neutralization buffer with 600 mM NaCl. Beads were incubated with 100 μl elution buffer (neutralization buffer with 600 mM NaCl plus 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol) to recover the bound proteins. This step releases the protein from the streptavidin bead leaving the biotin-HPDP tag bound to the bead as well as natively biotinylated proteins still bound to the bead. Four volumes of −20°C acetone were added, and samples were incubated for 1 h at −20°C to reprecipitate proteins. Samples were centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed and dried for proteomic analysis.

Protein digestion and mass spectrometry.

The Nevada Proteomics Center analyzed selected proteins by trypsin digestion and liquid chromotography (LC)/MS/MS analysis. Acetone-precipitated pellets were washed twice with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 100% acetonitrile, reduced, and alkylated using 10 mM dithiothreitol and 100 mM iodoacetamide and incubated with 75 ng sequencing grade-modified porcine trypsin (Promega, Fitchburg WI) in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate overnight at 37°C. Peptides were first separated by Michrom Paradigm Multi-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography (MDLC) instrument [Magic C18AQ 3μ 200Å (0.2 × 50 mm) column (Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA) with an Agilent ZORBAX 300SB-C18 5μ (5 × 0.3 mm) trap (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA)]. The gradient employed 0.1% formic acid in water (pump A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (pump B) as follows time (min), flow (μl/min), pump B (%): (0.00, 4.00, 5.00), (5.00, 4.00, 5.00), (95.00, 4.00, 45.00), (95.10, 4.00, 80.00), (96.10, 4.00, 80.00), (96.20, 4.00, 5.00). Eluted peptides were analyzed using a Thermo Finnigan LTQ-Orbitrap using Xcalibur v 2.0.7. MS spectra (m/z 300–2,000) were acquired in the positive ion mode with resolution of 60,000 in profile mode. The top 4 data-dependent signals were analyzed by MS/MS with CID activation, minimum signal of 50,000, isolation width of 3.0, and normalized collision energy of 35.0. The reject mass list included the following: 323.2040, 356.0690, 371.1010, 372.1000, 373.0980, 445.1200, 523.2840, 536.1650, 571.5509, 572.5680, 575.5494, 677.6090, 737.7063, 747.3510, 761.7316, 763.8791, 767.0623, 824.4870, 832.1884, 930.1760, 1106.0552, 1106.0564, 1142.0940, and 1150.0927. Dynamic exclusion settings were used with a repeat count of two, repeat duration of 10 s, exclusion list size of 500, and exclusion duration of 30 s.

Database searching.

MS/MS were extracted; charge state deconvolution and deisotoping were not performed. All MS/MS samples were analyzed using Sequest (version v.27, rev. 11; Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Sequest was initiated to search the database containing ipi.HUMAN.v3.87, the Global Proteome Machine cRAP v.2012.01.01, and random decoy sequences (183,158 entries) assuming the digestion enzyme trypsin. Sequest was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 1.00 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10 ppm. Oxidation of methionine, iodoacetamide derivative of cysteine, and n-ethylmaleimide on cysteine were specified in Sequest as variable modifications. The labels introduced in the Biotin Switch are removed when the disulfide linking Biotin-HPDP to the protein is cleaved after addition of β-mercaptoethanol and is therefore not considered during database searching. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository (42) with the dataset identifier PXD000226 and DOI 10.6019/PXD000226.

Criteria for protein identification.

PROTEOIQ (V2.6, www.nusep.com) was used to validate MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications. Peptides were parsed before analysis with a minimum Xcorr value of 1.5 and a minimum length of six amino acids. There were no matches to the concatenated decoy database, and therefore, a false discovery value is not applicable or “0.” Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at >95.0% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm (23). Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at >95.0% probability and contained at least two identified peptides with five spectra per peptide. Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm (29). Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony.

Controls.

Stringent controls were performed to avoid false positive identification of non-S-nitrosated cysteines that could have been mislabeled during the experimental procedures. These controls are standard when performing the biotin switch procedure and include removal of GSNO and/or ascorbate during the biotin switch. A small number of proteins were shown to be constitutively S-nitrosated and were labeled without the addition of GSNO. This is a common and expected result. Removal of ascorbate during the biotin switch removed any signal that was seen when ascorbate was present. Streptavidin purification of biotin switched proteins removes any signal from naturally biotinylated proteins, and these are therefore not present in our analysis. Streptavidin purification and LC/MS/MS analysis of ascorbate negative samples were shown to only contain the contaminating keratin proteins, trypsin and traces of serum albumin. Therefore, our ascorbat- positive sample identification contains almost no nonspecific binding proteins

Data analysis.

Area under the curve (AUC) data were analyzed using the in program statistical package provided with ProteoIQ. Spectral counting data were extracted from ProteoIQ and analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; www.graphpad.com. The statistical significance level for three-way comparisons of spectral counts and AUC measures was predetermined as 0.05. Statistical values for all quantitated proteins are given in Table 1. For quantitation, we used the nonredundant list of quantitative peptides with the following settings: mass tolerance 10 ppm, quantify two most abundant peaks, peak width of five scans, retention time variation of 300 s, and a precursor scan type of profile. For every precursor m/z, ProteoIQ locates the precursor scan and creates an extracted ion chromatogram for each m/z across all runs. It is important to note that a precursor m/z does not have to be identified in every run by MS/MS. As long as one MS/MS event has resulted in a peptide identification, ProteoIQ will search for the precursor m/z across all LC-MS/MS runs. As part of the Label-Free Quantification, ProteoIQ performs a global and local alignment procedure. Once alignment is complete, relative quantification can be performed by comparing the peak heights of the monoisotopic precursor m/z across each run. ProteoIQ further ensures accurate peak picking by modeling the theoretical isotopic distribution for each peptide and then aligning the theoretical distribution with the experimental isotopic envelope (1).

Table 1.

Statistical values for area under the curve analysis of quantitated proteins

| Sequence Id | Sequence Name | F Stat | P Value | Labor Log2 Rel Ex | Labor Log2 Rel Ex SD | Nonlabor Log2 Rel Ex | Nonlabor Log2 Rel Ex SD | Preterm Labor Log2 Rel Ex | Preterm Labor Log2 Rel Ex SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P02768 | ALBU | 235.07 | 0 | −0.14 | 0.58 | 0 | 0.33 | −2.01 | 0.95 |

| P60709 | ACTB | 9.19 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0 | 0.35 | −0.3 | 0.86 |

| P21333 | FLNA | 0.03 | 0.975 | −0.01 | 0.28 | 0 | 0.22 | −0.02 | 1.03 |

| P17661 | DESM | 0.67 | 0.514 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0 | 0.22 | 0.2 | 1.17 |

| P68871 | HBB | 92.08 | 0 | −0.1 | 0.55 | 0 | 0.2 | −2.5 | 1.42 |

| P35527 | K1C9 | 4.47 | 0.016 | −0.12 | 0.92 | 0 | 1 | 0.69 | 1.02 |

| P04792 | HSPB1 | 0.91 | 0.406 | 0.06 | 0.62 | 0 | 0.26 | 0.2 | 1.02 |

| P68363 | TBA1B | 3.76 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.28 | −0.19 | 0.85 |

| P69905 | HBA | 2.73 | 0.072 | −0.19 | 0.74 | 0 | 0.21 | −0.33 | 1.09 |

| P02042 | HBD | 67.72 | 4.4E-16 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.22 | −2.27 | 1.11 |

| P07437 | TBB5 | 1.24 | 0.301 | −0.03 | 0.46 | 0 | 0.26 | −0.24 | 0.72 |

| P14618 | KPYM | 137.65 | 0 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0 | 0.33 | −2.16 | 0.48 |

| P08670 | VIME | 0.13 | 0.879 | −0.06 | 0.65 | 0 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 1.26 |

| P06733 | ENOA | 5.14 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.4 | −0.15 | 0.45 |

| P04264 | K2C1 | 2.55 | 0.093 | −0.16 | 0.86 | 0 | 1.02 | 0.6 | 0.93 |

| O14558 | HSPB6 | 0.62 | 0.542 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 1.22 |

| Q8WX93 | PALLD | 47.85 | 5.7E-12 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0 | 0.35 | −2.13 | 1.27 |

| Q01995 | TAGL | 8.72 | 0.001 | −0.05 | 0.62 | 0 | 0.39 | 1.15 | 1.43 |

| P06753 | TPM3 | 0.14 | 0.866 | −0.12 | 1.34 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.14 | 1.45 |

| P09211 | GSTP1 | 80.82 | 6.1E-13 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0 | 0.23 | −2.74 | 0.79 |

| Q15746 | MYLK | 19.23 | 1.11E-4 | −0.02 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.35 | −1.56 | 0.82 |

| Q93052 | LPP | 25.42 | 3.66E-6 | −0.11 | 0.81 | 0 | 0.27 | −1.68 | 0.71 |

| P12277 | KCRB | 39.49 | 0 | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0 | 0.35 | −1.49 | 0.56 |

| P62937 | PPIA | 5.61 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.71 | 0 | 0.29 | 0.69 | 0.7 |

| Q14315 | FLNC | 0.87 | 0.433 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0 | 0.24 | −0.13 | 0.79 |

| P04406 | G3P | 6.63 | 0.005 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.29 | −0.87 | 0.82 |

| O00151 | PDLI1 | 9.17 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.68 | 0 | 0.4 | −1.49 | 1.09 |

| P04083 | ANXA1 | 0.6 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.77 | −0.06 | 0.88 |

| P09382 | LEG1 | 22.35 | 1.79E-8 | −0.2 | 0.68 | 0 | 0.59 | −2.36 | 0.95 |

| Q14195 | DPYL3 | 4.5 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0 | 0.27 | −0.49 | 0.56 |

| P60660 | MYL6 | 13.43 | 3.58E-5 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0 | 0.16 | 1.32 | 0.65 |

| O43707 | ACTN4 | 12.21 | 0.001 | −0.38 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.21 | −1.35 | 1.04 |

| P21291 | CSRP1 | 0.47 | 0.633 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 1.06 |

| Q9NZN4 | EHD2 | 5.24 | 0.019 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0 | 0.33 | −0.82 | 1.05 |

| P18206 | VINC | 21.99 | 5.86E-5 | −0.59 | 0.48 | 0 | 0.52 | −2.15 | 1.11 |

| P51911 | CNN1 | 11.01 | 1.87E-4 | −0.64 | 0.54 | 0 | 0.36 | 2.16 | 1.22 |

| P31949 | S10AB | 0.26 | 0.782 | 0.03 | 1.06 | 0 | 0.34 | −0.5 | 1.59 |

| P08779 | K1C16 | 0 | 1 | −10 | 0 | −10 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| O00299 | CLIC1 | 7.46 | 0.014 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0 | 0.2 | −1.59 | 0.94 |

| P07355 | ANXA2 | 1.28 | 0.343 | 0.2 | 0.57 | 0 | 0.57 | −0.66 | 0.94 |

| P02787 | TRFE | 2.49 | 0.164 | −0.83 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.48 | −0.57 | 0.91 |

| P68104 | EF1A1 | 3.73 | 0.089 | −0.08 | 0.61 | 0 | 0.51 | −1.2 | 0.86 |

| P00387 | NB5R3 | 1.44 | 0.309 | 0.49 | 1.13 | 0 | 0.7 | −0.85 | 1.09 |

| Q15124 | PGM5 | 1.23 | 0.358 | 0.16 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.63 | −0.76 | 1.07 |

| P47756 | CAPZB | 0.38 | 0.706 | 0 | 0.96 | 0 | 0.52 | −0.72 | 0 |

| P01009 | A1AT | 0.12 | 0.891 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.81 |

| Q53GG5 | PDLI3 | 0.18 | 0.842 | −0.25 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.63 | 0 | 0.92 |

| P24844 | MYL9 | 5.14 | 0.001 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0 | 0.29 | 1.35 | 0.93 |

| P01857 | IGHG1 | 5.25 | 0.048 | −0.24 | 0.26 | 0 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.84 |

| O95678 | K2C75 | 0.74 | 0.515 | 0.47 | 0.91 | 0 | 1.25 | 0.89 | 1.31 |

| Q9UMS6 | SYNP2 | 0 | 1 | −10 | 0 | −10 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| P07737 | PROF1 | 13.33 | 5.76E-5 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.23 | 2.12 | 1.01 |

| Q9NR12 | PDLI7 | 0.46 | 0.657 | −0.19 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.96 |

| P08133 | ANXA6 | 16.16 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0 | 0.47 | −2.17 | 0.88 |

| P10599 | THIO | 0.013 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0 | 0.46 | 1.639 | 0.54 |

Statistical analysis of quantitated proteins showing the F Statistic, P Value, Log2 Relative Expression, and Log2 Relative Expression Standard Deviation of Laboring, Nonlaboring, and Preterm Laboring samples. Data was extracted from area under the curve analysis of extracted ion chromatograms from ProteoIQ.

Pathway analysis.

In conjunction with our bioinformatics core we used Ingenuity computational pathway analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA) software to elucidate the global implications of differentially S-nitrosated proteins in preterm labor patients. IPA was applied to identify potentially perturbed molecular pathways and networks in preterm labor patients. The IPA program uses a knowledge database derived from the literature to relate the proteins to each other, based on their interaction and function. The knowledge base consists of a high-quality expert-curated database containing 1.5 million biological findings consisting of >42,000 mammalian genes and pathway interactions extracted from the literature. In brief, proteins that were confidently identified and showed a statistically significant change (±log2 1, P > 0.05) were considered for IPA analysis. The IPA software then used these proteins and their identifiers to navigate the curated literature database and extract overlapping network(s) between the candidate proteins. Associated networks were generated, along with a score representing the log probability of a particular network being found by random chance. Top canonical pathways associated with the uploaded data were presented, along with a P value. Furthermore, upstream regulators that are likely to be responsible for the observed changes were predicted to be activated or inhibited. The P values were calculated using right-tailed Fisher's exact tests. IPA also uses a z-score algorithm to reduce the chance that random data will generate significant predictions. (The complete list of peptide and protein identification data can be found in Table S1 in the online Supplemental Material at the Am J Physiol Cell Physiol website.)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

S-nitrosoproteome in disparate states of human pregnancy.

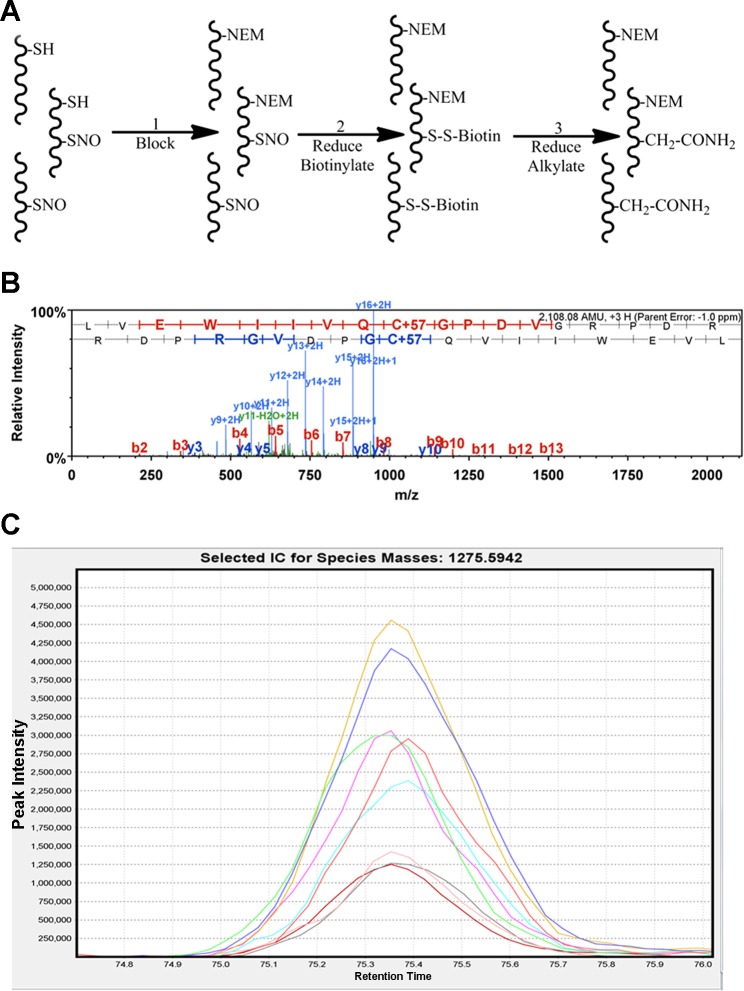

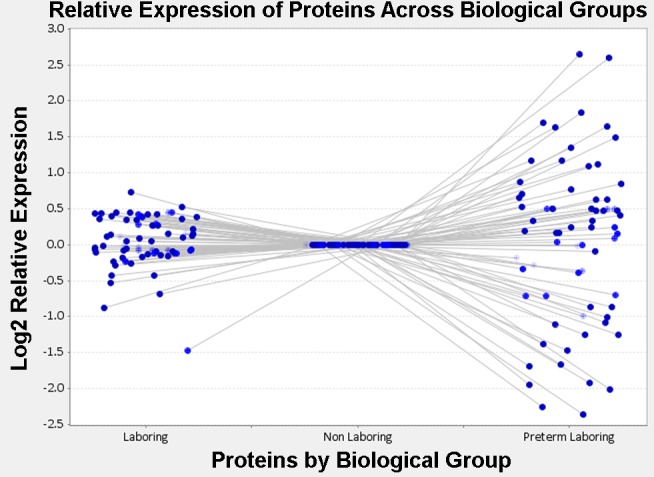

With samples obtained under informed consent, we compared GSNO-mediated S-nitrosation in spontaneously laboring term (12 patients ranging from 37 to 41 wk) and spontaneously laboring preterm myometrium (12 patients ranging from 29 to 36 wk) to the nonlaboring state of term pregnancy myometrium (12 patients ranging from 37 to 41 wk) in women. By combining the biotin switch technique (21), streptavidin purification, and high-accuracy LC/MS/MS analysis, we unambiguously identified 110 HUSM proteins that can be S-nitrosated in 1 or more conditions of pregnancy (Table 2). The use of a differential blocking and labeling technique (Fig. 2) allowed us to identify the modified cysteine(s) that are either S-nitrosated or reversibly oxidized on 118 peptides corresponding to 56 of the identified proteins (Table 3). All known disulfide-forming cysteines were removed from this list, and we provide it as a supplementary guide to help identify those cysteines that are modified under the NO signaling conditions applied. Additionally, expression levels of 62 of the 110 proteins were quantified using normalized spectral counts and AUC measures of extracted ion chromatograms. We employed both quantification measures because spectral counting, while using dynamic exclusion, limits the quantitative capability to a relative measurement between states and we wanted to verify that the number of MS2 events per peptide were indicative of the amount of peptide that was measured by AUC of the MS1 chromatograms. A simple ANOVA demonstrated that 26 of these proteins exhibited statistically significant differences across the three conditions, specified by an F statistic P value of P < 0.05. These proteins had log2 fold changes of at least ±1 in preterm laboring patients compared with nonlaboring patients (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

S-nitrosoproteome in pregnancy

| Sequence Id | Sequence Name | Main Function | Total Peptides | L Log2 Rel Exp | PTL Log2 Rel Exp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P21333 | Filamin-A | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 175 | −0.22 | 0.55 |

| P02768 | Serum albumin | Transporter | 78 | −0.16 | −1.44 |

| P63267 | Actin, gamma-enteric smooth muscle | Smooth muscle contraction | 48 | 0.11 | 0.53 |

| P63261 | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 44 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| P17661 | Desmin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 39 | 0.1 | 1.25 |

| Q9Y490 | Talin-1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 33 | −0.71 | −2.48 |

| P68871 | Hemoglobin subunit-beta | Transporter | 26 | −0.14 | −2.22 |

| P18206 | Vinculin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 26 | −0.65 | −1.53 |

| P51911 | Calponin-1 | Smooth muscle contraction | 26 | −0.78 | 1.4 |

| Q14315 | Filamin-C | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 27 | 0 | 0.2 |

| P04264 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 | Structural | 25 | −0.19 | 0.99 |

| P14618 | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | Metabolic enzyme | 23 | 0.41 | −1.32 |

| P35527 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 | Structural | 21 | −0.19 | 1.31 |

| Q8WX93 | Palladin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 20 | 0.27 | −1.42 |

| Q93052 | Lipoma-preferred partner | Transporter and scaffolding | 21 | −0.08 | −1.35 |

| Q01995 | Transgelin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 18 | −0.1 | 1.69 |

| P06733 | Alpha-enolase | Metabolic enzyme | 16 | 0.38 | 0.09 |

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Metabolic enzyme | 15 | −0.18 | −0.12 |

| P09211 | Glutathione S-transferase P | Nitric oxide signaling | 13 | 0.39 | −2.53 |

| P02042 | Hemoglobin subunit-delta | Transporter | 16 | 0.09 | −1.83 |

| P08670 | Vimentin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 17 | −0.18 | 0.21 |

| P09382 | Galectin-1 | Scaffolding | 15 | −0.26 | −2.04 |

| P13645 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 | Structural | 13 | −0.63 | 0.45 |

| P35908 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 2 epidermal | Structural | 13 | 0.22 | 0.9 |

| P04792 | Heat shock protein beta-1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 12 | 0.09 | 0.63 |

| P12277 | Creatine kinase B-type | Metabolic enzyme | 12 | −0.25 | −1.19 |

| P69905 | Hemoglobin subunit-alpha | Transporter | 13 | −0.29 | 0.03 |

| P12814 | Alpha-actinin-1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 12 | −0.36 | −1.13 |

| P67936 | Tropomyosin alpha-4 chain | Smooth muscle contraction | 13 | 0.31 | 0.78 |

| P13639 | Elongation factor 2 | Transcriptional regulation | 10 | 0.05 | −1.09 |

| P10768 | S-formylglutathione hydrolase | Metabolic enzyme | 10 | 0.4 | −1.16 |

| O00151 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 1 | Transcriptional regulation | 10 | −0.04 | −1.27 |

| P68363 | Tubulin alpha-1B chain | Structural | 9 | 0.09 | 0.43 |

| Q71U36 | Tubulin alpha-1A chain | Structural | 9 | 0.09 | 0.43 |

| O14558 | Heat shock protein beta-6 | Smooth muscle contraction | 9 | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| Q14195 | Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 3 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 11 | 0.08 | −0.04 |

| P08133 | Annexin A6 | Smooth muscle contraction | 10 | 0.25 | −1.47 |

| P07437 | Tubulin beta chain | Structural | 9 | −0.06 | 0.23 |

| P07951 | Tropomyosin beta chain | Smooth muscle contraction | 11 | 0.31 | 0.78 |

| Q15746 | Myosin light chain kinase, smooth muscle | Smooth muscle contraction | 9 | 0.17 | −0.3 |

| P62937 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | Protein binding | 9 | −0.03 | 1.15 |

| P48668 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6C | Structural | 9 | 0.06 | 1.29 |

| P68371 | Tubulin beta-4B chain | Protein binding | 8 | −0.09 | 0.2 |

| P21291 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 10 | 0.29 | 0.48 |

| Q562R1 | Beta-actin-like protein 2 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 9 | 0.43 | 0.19 |

| P01009 | Alpha-1-antitrypsin | Peptidase inhibitor | 7 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| P55072 | Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase | Protein binding and transport | 8 | −0.05 | −0.76 |

| P09493 | Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 9 | 0.31 | 0.78 |

| Q6PEY2 | Tubulin alpha-3E chain | Structural | 7 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| P54652 | Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 | Protein binding | 7 | 0.42 | −1.55 |

| P08779 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 16 | Structural | 7 | 0.57 | 1.5 |

| P04075 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | Metabolic enzyme | 7 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

| Q9NZN4 | EH domain-containing protein 2 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 6 | 0.12 | −0.77 |

| P07355 | Annexin A2 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 5 | −0.42 | −0.49 |

| P13647 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 5 | Structural | 6 | −0.25 | 1.21 |

| P02533 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 14 | Structural | 6 | 0.43 | 1.7 |

| P06396 | Gelsolin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 4 | −0.28 | 0.67 |

| Q15942 | Zyxin | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 5 | 0.08 | −0.56 |

| P60660 | Myosin light polypeptide 6 | Smooth muscle contraction | 6 | 0.21 | 1.58 |

| P68104 | Elongation factor 1-alpha 1 | Transcriptional regulation | 4 | −0.07 | −0.65 |

| Q5VTE0 | Putative elongation factor 1-alpha-like 3 | Transcriptional regulation | 4 | −0.07 | −0.65 |

| P13489 | Ribonuclease inhibitor | Protein binding | 4 | 0.21 | −0.36 |

| P07737 | Profilin-1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 5 | 0.48 | 2.23 |

| Q53GG5 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 3 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 5 | −0.39 | 0.36 |

| P23142 | Fibulin-1 | Protein binding | 4 | −0.55 | −0.91 |

| P37802 | Transgelin-2 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 5 | 0.48 | 1 |

| Q01518 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 4 | 0.3 | −0.28 |

| P21980 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | Protein crosslinking | 4 | 0.11 | −2.34 |

| Q09666 | Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK | Protein binding | 5 | −0.18 | 0.46 |

| Q15124 | Phosphoglucomutase-like protein 5 | Metabolic enzyme | 4 | 0.16 | −0.29 |

| O43707 | Alpha-actinin-4 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 4 | −0.38 | −0.89 |

| P31949 | Protein S100-A11 | Calcium signaling | 4 | 0.45 | 0.26 |

| P01857 | Ig gamma-1 chain C region | Protein binding | 5 | −0.53 | 0.34 |

| P24844 | Myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9 | Smooth muscle contraction | 3 | 0.37 | 1.82 |

| Q99497 | Protein DJ-1 | Redox response | 4 | 0.14 | −1.11 |

| P00387 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 3 | Biosynthesis | 4 | 0.6 | −0.33 |

| Q05682 | Caldesmon | Smooth muscle contraction | 5 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| P00338 | L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | Metabolic enzyme | 3 | −0.3 | −0.41 |

| P10809 | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | Chaperone | 2 | −0.19 | −0.5 |

| Q9NR12 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 7 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 4 | −0.6 | 0.13 |

| Q16881 | Thioredoxin reductase 1, cytoplasmic | Redox response | 3 | 0.21 | −0.67 |

| P01834 | Ig kappa chain C region | Protein binding | 3 | −0.32 | 0.33 |

| P49419 | Alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase | Metabolic enzyme | 3 | 0.69 | −1.45 |

| P02787 | Serotransferrin | Transporter | 2 | −0.44 | 0.31 |

| O00299 | Chloride intracellular channel protein 1 | Redox response | 3 | 0.46 | −0.55 |

| P02766 | Transthyretin | Transporter | 3 | −0.23 | 0.34 |

| P04083 | Annexin A1 | Phospholipid binding | 2 | 0.69 | 0.98 |

| P50395 | Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor beta | GTPase regulation | 2 | 0.38 | −0.95 |

| P04179 | Superoxide dismutase [Mn], mitochondrial | Redox response | 2 | 0.66 | 0.07 |

| Q9UBQ7 | Glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase | Metabolic enzyme | 2 | 0.1 | −1.72 |

| O60478 | Integral membrane protein GPR137B | G-Protein receptor | 3 | −0.72 | 0.83 |

| P00441 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | Redox response | 2 | −0.22 | 0.5 |

| P01861 | Ig gamma-4 chain C region | Protein binding | 3 | −0.24 | 0.66 |

| P14550 | Alcohol dehydrogenase [NADP+] | Metabolic enzyme | 2 | 0.74 | −0.52 |

| P02652 | Apolipoprotein A-II | Transporter | 2 | −1.51 | −0.24 |

| P62508 | Estrogen-related receptor gamma | Hormone receptor | 3 | −1.92 | −2.04 |

| P10599 | Thioredoxin | Redox response | 2 | 0.22 | 1.04 |

| P16591 | Tyrosine-protein kinase Fer | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 3 | −0.05 | −1 |

| P35754 | Glutaredoxin-1 | Redox response | 2 | −0.78 | −0.28 |

| P47756 | F-actin-capping protein subunit-beta | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 2 | −0.3 | −1.1 |

| P60953 | Cell division control protein 42 homolog | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 2 | 0.12 | −1.09 |

| P31040 | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial | Metabolic enzyme | 2 | −0.89 | −2.42 |

| Q13371 | Phosducin-like protein | Protein binding | 2 | −0.23 | −0.33 |

| P01876 | Ig alpha-1 chain C region | Protein binding | 2 | −0.17 | −0.35 |

| P06703 | Protein S100-A6 | Calcium signaling | 2 | −0.96 | −0.06 |

| Q9UMS6 | Synaptopodin-2 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 2 | Not Id'd | 10 |

| Q6IE37 | Ovostatin homolog 1 | Proteinase inhibito | 2 | −1.11 | −0.15 |

| Q5SVZ6 | Zinc finger MYM-type protein 1 | Protein binding | 2 | −0.28 | 0.71 |

| O75083 | WD repeat-containing protein 1 | Cytoskeletal dynamics | 2 | 0.15 | −1.08 |

| Q9ULJ3 | Zinc finger protein 295 | Transcriptional regulation | 2 | −0.09 | −1.34 |

There were 110 S-nitrosated proteins identified with 2 or more unique peptides. Log2 relative expressions for labor and preterm labor (L/PTL Rel Ex) for these 110 proteins are based on area under the curve analysis of all identified peptides using the nonlaboring state as reference. Note synaptopodin-2 was only positively identified in PTL.

Fig. 2.

Labeling, purification, and quantitation of S-nitrosated proteins using a modified biotin-switch technique and high mass accuracy liquid chromotography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). A: modified biotin-switch. Step 1: N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) is used in place of methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) to block free nonnitrosylated thiols. Step 2: S-nitrosylated thiols are selectively reduced using ascorbate, labeled with a thiol reactive biotin tag, and purified using streptavidin resin. Step 3: biotin-labeled thiols are reduced and alkylated to allow for identification of S-NO sites. B: representative MS/MS spectra of a carbamidomethyl labeled S-NO peptide from transgelin. Note the 57-Da shift on the identified cysteine which is indicative of carbamidomethylation. C: representative extracted ion chromatogram of a single peptide quantitated in all 9 replicates. Each line is indicative of an individual sample.

Table 3.

S-nitrosated or reversibly oxidized cysteine residues identified by mass shift labeling

| Sequence Id | Sequence Name | S-NO Peptide(s) | S-NO-Cysteine(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P02768 | Serum albumin | ALVLIAFAQYLQQC*PFEDHVKLVNEVTEFAK | C*58 |

| P21333 | Filamin-A | AEISC*TDNQDGTC*SVSYLPVLPGDYSILVK | C*1912, C*1920 |

| AHVVPC*FDASK | C*1157 | ||

| ALGALVDSC*APGLC*PDWDSWDASKPVTNAR | C*205, C*210 | ||

| ALGALVDSC*APGLC#PDWDSWDASKPVTNAR | C*205, C#210 | ||

| APLRVQVQDNEGC*PVEALVK | C*717 | ||

| APSVANVGSHC*DLSLKIPEISIQDMTAQVTSPSGK | C*2160 | ||

| ATC*APQHGAPGPGPADASK | C*2543 | ||

| C*APGVVGPAEADIDFDIIRNDNDTFTVK | C*810 | ||

| C*SGPGLSPGMVR | C*1453 | ||

| IVGPSGAAVPC*KVEPGLGADNSVVRFLPR | C*1018 | ||

| LQVEPAVDTSGVQC*YGPGIEGQGVFR | C*1260 | ||

| MDC*QEC*PEGYRVTYTPMAPGSYLISIK | C*2476, C*2479 | ||

| MDC#QEC*PEGYRVTYTPMAPGSYLISIK | C#2479, C*2479 | ||

| SPYTVTVGQAC*NPSAC*R | C*478, C*483 | ||

| SPYTVTVGQAC*NPSAC#RAVGRGLQPK | C*478, C#483 | ||

| P60709 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | SPYTVTVGQAC#NPSAC*R | C#478, C*483 |

| THEAEIVEGENHTYC*IR | C*2199 | ||

| VEYTPYEEGLHSVDVTYDGSPVPSSPFQVPVTEGC*DPSR | C*1353 | ||

| VGSAADIPINISETDLSLLTATVVPPSGREEPC*LLK | C*1997 | ||

| VQVQDNEGC*PVEALVKDNGNGTYSC#SYVPR | C*717 | ||

| VTYC*PTEPGNYIINIK | C*2107 | ||

| YWPQEAGEYAVHVLC*NSEDIR | C*649 | ||

| C*DVDIRKDLYANTVLSGGTTMYPGIADR | C*285 | ||

| FRC*PEALFQPSFLGMESC*GIHETTFNSIMK | C*257, C*272 | ||

| FRC#PEALFQPSFLGMESC*GIHETTFNSIMK | C#257, C*272 | ||

| FRC*PEALFQPSFLGMESC#GIHETTFNSIMK | C*257, C#272 | ||

| EKLC*YVALDFEQEMATAASSSSLEK | C*217 | ||

| P62736 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle | C*DIDIRKDLYANNVLSGGTTMYPGIADR | C*287 |

| C*PETLFQPSFIGMESAGIHETTYNSIMK | C*259 | ||

| EKLC*YVALDFENEMATAASSSSLEK | C*219 | ||

| P51911 | Calponin-1 | IGNNFMDGLKDGIILC*EFINKLQPGSVK | C*61 |

| RQIFEPGLGMEHC*DTLNVSLQMGSNKGASQR | C*238 | ||

| YC*LTPEYPELGEPAHNHHAHNYYNSA | C*273 | ||

| Q93052 | Lipoma-preferred partner | AYC#EPC#YINTLEQC*NVC*SKPIMER | C#465, C#468, C*476, C*480 |

| AYHPHC*FTC*VMC*HR | C*499, C*502, C*505 | ||

| AYHPHC#FTC*VMC*HR | C#499, C*502, C*505 | ||

| C*SVC*KEPIMPAPGQEETVR | C*536, C*539 | ||

| IVALDRDFHVHC*YR | C*566 | ||

| KTYITDPVSAPC*APPLQPK | C*364 | ||

| P68871 | Hemoglobin subunit-beta | SAQPSPHYMAAPSSGQIYGSGPQGYNTQPVPVSGQC*PPPSTR | C*262 |

| SLDGIPFTVDAGGLIHC*IEDFHKK | C*524 | ||

| VLGAFSDGLAHLDNLKGTFATLSELHC*DKLHVDPENFR | C*94 | ||

| LLGNVLVC*VLAHHFGKEFTPPVQAAYQK | C*113 | ||

| P14618 | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | AEGSDVANAVLDGADC*IMLSGETAKGDYPLEAVR | C*358 |

| AGKPVIC*ATQMLESMIK | C*326 | ||

| GIFPVLC*KDPVQEAWAEDVDLRVNFAMNVGK | C*474 | ||

| NTGIIC*TIGPASR | C*497 | ||

| P09382 | Galectin-1 | SFVLNLGKDSNNLC*LHFNPR | C*43 |

| FNAHGDANTIVC*NSKDGGAWGTEQR | C*61 | ||

| EAVFPFQPGSVAEVC*ITFDQANLTVK | C*89 | ||

| P13489 | Ribonuclease inhibitor | ELDLSNNC*LGDAGILQLVESVR | C*409 |

| TLPTLQELHLSDNLLGDAGLQLLC*EGLLDPQC*RLEK | C*134, C*142 | ||

| WAELLPLLQQC*QVVR | C*30 | ||

| P17661 | Desmin | QEMMEYRHQIQSYTC*EIDALKGTNDSLMR | C*333 |

| P04264 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 | MSGEC*APNVSVSVSTSHTTISGGGSR | C*497 |

| SGGGGGRFSSC*GGGGGSFGAGGGFGSR | C*49 | ||

| Q15746 | Myosin light chain kinase, smooth muscle | FDC*KIEGYPDPEVVWFKDDQSIR | C*1830 |

| HFQIDYDEDGNC*SLIISDVC*GDDDAKYTC*K | C*1865, C*1873, C*1882 | ||

| QAQVNLTVVDKPDPPAGTPC*ASDIR | C*1339 | ||

| Q9Y490 | Talin-1 | ALC*GFTEAAAQAAYLVGVSDPNSQAGQQGLVEPTQFAR | C*1434 |

| EC*ANGYLELLDHVLLTLQKPSPELK | C*2243 | ||

| TMQFEPSTMVYDAC*R | C*29 | ||

| P13645 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 | GSSGGGC*FGGSSGGYGGLGGFGGGSFR | C*66 |

| YC*VQLSQIQAQISALEEQLQQIR | C*401 | ||

| O14558 | Heat shock protein beta-6 | LFDQRFGEGLLEAELAALC*PTTLAPYYLR | C*46 |

| P68363 | Tubulin alpha-1B chain | AVC*MLSNTTAIAEAWAR | C*376 |

| AYHEQLSVAEITNAC*FEPANQMVK | C*295 | ||

| O00151 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 1 | AALANLC*IGDVITAIDGENTSNMTHLEAQNR | C*45 |

| IKGC*TDNLTLTVAR | C*73 | ||

| P69905 | Hemoglobin subunit-alpha | LLSHC*LLVTLAAHLPAEFTPAVHASLDKFLASVSTVLTSK | C*105 |

| P68104 | Elongation factor 1-alpha 1 | NMITGTSQADC*AVLIVAAGVGEFEAGISK | C*111 |

| SGDAAIVDMVPGKPMC*VESFSDYPPLGR | C*411 | ||

| Q5VTE0 | Putative elongation factor 1-alpha-like 3 | NMITGTSQADC*AVLIVAAGVGEFEAGISK | C*111 |

| SGDAAIVDMVPGKPMC*VESFSDYPPLGR | C*411 | ||

| P00338 | L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | GLYGIKDDVFLSVPC*ILGQNGISDLVK | C*293 |

| LGVHPLSC*HGWVLGEHGDSSVPVWSGMNVAGVSLK | C*185 | ||

| Q53GG5 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 3 | AAAANLC*PGDVILAIDGFGTESMTHADAQDR | C*44 |

| P08779 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 16 | ISSVLAGGSC*RAPSTYGGGLSVSSR | C*40 |

| YC*MQLSQIQGLIGSVEEQLAQLR | C*369 | ||

| Q01518 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | ALLVTASQC*QQPAENKLSDLLAPISEQIK | C*93 |

| P67936 | Tropomyosin alpha-4 chain | EENVGLHQTLDQTLNELNC*I | C*247 |

| P62937 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | HTGPGILSMANAGPNTNGSQFFIC*TAK | C*115 |

| IIPGFMC*QGGDFTR | C*62 | ||

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | IISNASC*TTNC#LAPLAK | C*152 |

| IISNASC#TTNC*LAPLAK | C*156 | ||

| P10768 | S-formylglutathione hydrolase | SVSAFAPIC*NPVLC*PWGK | C*176, C*181 |

| SYPGSQLDILIDQGKDDQFLLDGQLLPDNFIAAC*TEK | C*243 | ||

| P23142 | Fibulin-1 | RGYQLSDVDGVTC*EDIDEC*ALPTGGHIC*SYR | C*479, C*485, C*494 |

| C*LAFEC*PENYRR | C*551, C*556 | ||

| Q14315 | Filamin-C | FGGEHIPNSPFHVLAC*DPLPHEEEPSEVPQLR | C*1735 |

| SPFPVHVSEAC*NPNAC#R | C*472 | ||

| P02042 | Hemoglobin subunit-delta | GTFSQLSELHC*DKLHVDPENFR | C*113 |

| P06733 | Alpha-enolase | SGETEDTFIADLVVGLC*TGQIK | C*389 |

| Q9NZN4 | EH domain-containing protein 2 | FMC*AQLPNQVLESISIIDTPGILSGAK | C*138 |

| P21291 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1 | GLESTTLADKDGEIYC*K | C*170 |

| NLDSTTVAVHGEEIYC*K | C*58 | ||

| P09211 | Glutathione S-transferase P | TLGLYGKDQQEAALVDMVNDGVEDLRC*K | C*102 |

| P07355 | Annexin A2 | EVKGDLENAFLNLVQC*IQNKPLYFADR | C*262 |

| P02787 | Serotransferrin | SAGWNIPIGLLYC*DLPEPR | C*156 |

| P07437 | Tubulin beta chain | LTTPTYGDLNHLVSATMSGVTTC*LR | C*239 |

| Q8WX93 | Palladin | RLLGADSATVFNIQEPEEETANQEYKVSSC*EQR | C*964 |

| P04075 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | ALSDHHIYLEGTLLKPNMVTPGHAC*TQK | C*240 |

| Q01995 | Transgelin | LVEWIIVQC*GPDVGRPDR | C*38 |

| P24844 | Myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9 | NAFAC*FDEEASGFIHEDHLR | C*109 |

| P35527 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 | YC*GQLQMIQEQISNLEAQITDVR | C*406 |

| P12277 | Creatine kinase B-type | SKDYEFMWNPHLGYILTC*PSNLGTGLR | C*283 |

| P48668 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6C | ISIGGGSC*AISGGYGSR | C*77 |

| P08670 | Vimentin | QVQSLTC*EVDALKGTNESLER | C*328 |

| Q14195 | Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 3 | AITIASQTNC*PLYVTK | C*248 |

| P54652 | Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 | GPAIGIDLGTTYSC*VGVFQHGK | C*18 |

| Q99497 | Protein DJ-1 | GLIAAIC*AGPTALLAHEIGFGSK | C*106 |

| P60660 | Myosin light polypeptide 6 | ILYSQC*GDVMR | C*32 |

| P47756 | F-actin-capping protein subunit-beta | NLSDLIDLVPSLC*EDLLSSVDQPLK | C*36 |

| P02652 | Apolipoprotein A-II | EPC*VESLVSQYFQTVTDYGKDLMEK | C*29 |

| Q15942 | Zyxin | C*SVC*SEPIMPEPGRDETVR | C*504, C*507 |

| O00299 | Chloride intracellular channel protein 1 | EEFASTC*PDDEEIELAYEQVAK | C*223 |

| P01861 | Ig gamma-4 chain C region | WQEGNVFSC*SVMHEALHNHYTQK | C*305 |

Note some peptides were found in multiple states of S-nitrosation all of which were included in this table.

S-nitrosated cysteines;

non-S-nitrosated cysteines.

Fig. 3.

Relative expression profile of the human uterine smooth muscle (HUSM) S-nitrosoproteome in disparate states of pregnancy. Dots are representative of individual S-nitrosated proteins present in all 3 states of pregnancy. Nonlaboring was designated as the baseline state and laboring and preterm laboring conditions are compared by log2 relative expression of area under the curve of extracted ion chromatograms.

The ability to S-nitrosate proteins in pregnant myometrium might reasonably be suggested to rely principally on the abundance of any particular protein and the availability of a free cysteine thiol. To verify that changes at the total protein level were not responsible for differences in the levels of S-nitrosation measured, we semiquantitatively measured by spectral counting the relative changes of the total proteome in each condition of pregnancy using two-dimensional LC/MS/MS analysis. Our study showed clearly that changes in S-nitrosation were independent of changes in total protein levels among those proteins identified. Thus the difference in S-nitrosation levels of a given protein in one pregnancy state vs. another is a consequence of the state of pregnancy and not the apparent availability of reactive NO or the level of protein thiol substrate. Other putative distinctions that would permit increased or decreased S-nitrosation of a given protein in one or more states of pregnancy is not known but may result in differences in the function of that protein. Such differences in myometrium from patients in labor preterm may be associated mechanistically with early labor.

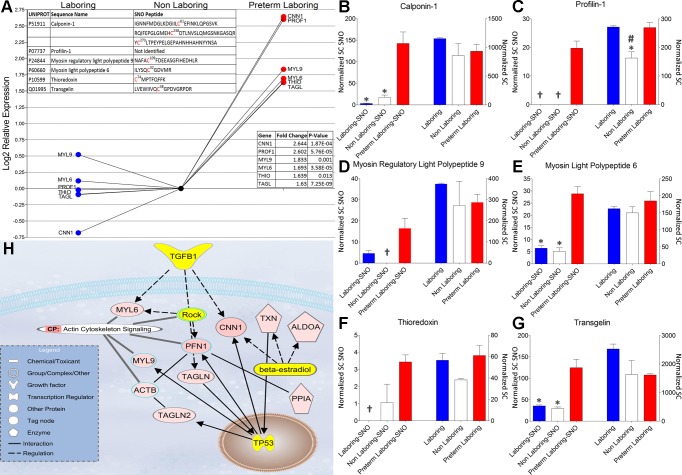

Upregulation S-nitrosation in preterm labor.

Examination of our findings using IPA (Ingenuity Systems) shows that several of the S-nitrosated proteins that are up-S-nitrosated fit into functionally interesting protein groupings that are disparately regulated at the posttranslational level. Interestingly, the pathway involving actin cytoskeleton dynamics (Fig. 4) shows a statistically significant increase in S-nitrosation of several key regulatory proteins including calponin-1 (CNN1), profilin-1 (PFN1), myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9 (MYL9), myosin light polypeptide 6 (MYL6), thioredoxin (THIO), and transgelin (TAGLN). The role of S-nitrosation in regulating these proteins is not completely understood particularly in the context of an interactome in pregnant myometrium. Each of these proteins has been shown to play a role in regulating smooth muscle contraction or nitric oxide signaling. In vitro S-nitrosation of skeletal muscle myosin, for example, increases the force of the acto-myosin interaction while decreasing its velocity indicative of the relaxed state (12). The calcium binding protein CNN1 has been shown to participate in regulating smooth muscle contraction by binding actin and inhibiting the actin-myosin interaction (8, 43). This tonic inhibition of the ATPase activity of myosin in smooth muscle is blocked by Ca2+-calmodulin, which inhibits CNN1-actin binding (28). PFN1 is essential in signaling cascades that modulate smooth muscle contraction through regulation of actin polymerization rather than MYL9 phosphorylation (38). Transgelin (also designated SM22α and p27) is a 22-kDA smooth muscle protein that physically associates with cytoskeletal actin filament bundles in contractile smooth muscle cells. Studies in transgelin knockout mice have demonstrated a pivotal role for transgelin in the regulation of Ca2+-independent contractility (22). Transgelin has also been implicated in induction of actin polymerization and/or stabilization of F-actin and is proposed to be necessary for actin polymerization and bundling (17). Considered together, these proteins constitute a potential interactome and discovering their behavior as S-nitrosated proteins may further our understanding of contraction-relaxation signaling in myometrium.

Fig. 4.

Proteins of interest that show a statistically significant increase in S-nitrosation during preterm labor. A: log2 relative expression of the area under the curve of extracted ion chromatograms. Top inset: identification of protein as well as any S-nitrosated peptides that were identified by LC/MS/MS. Bottom inset: gene identification, log2 fold change, and P value for identified proteins. B–G: relative expression of normalized spectral counts of S-nitrosated protein (Normalized SC SNO) levels (left 3 bars of each graph) and total protein levels (right 3 bars of each graph) from experiment matched samples. *P < 0.05, when comparing NL and or L to PTL. #P < 0.05, when comparing NL to L and PTL. †No spectral counts were observed. H: Ingenuity pathway analysis of statistically significant increased S-nitrosated proteins (red) as well as their nearest connecting neighbors (yellow). TGFB1; transforming growth factor beta-1; MYL6, myosin light polypeptide 6; MYL9, myosin regulatory light polypeptide 9; ACTB, actin, cytoplasmic 2; TAGLN, transgelin-2; ROCK, Rho-associated protein kinase 1; PFN1, profiling-1; TAGLN, transgelin-1; CNN1, calponin-1; TXN, thioredoxin; ALDOA, fructose-bisphosphate alodolase A; PPIA, peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A; TP53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (TP53).

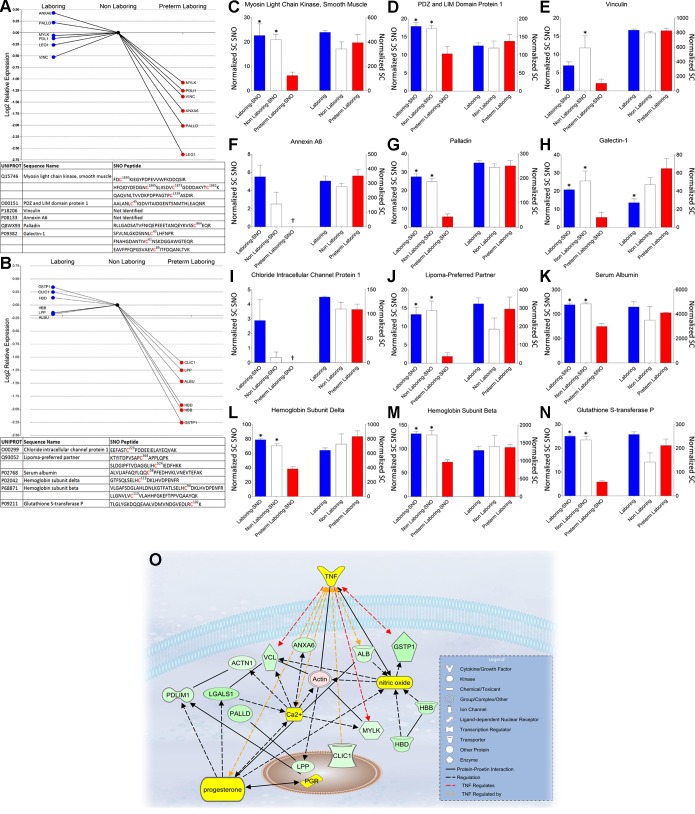

Downregulation of S-nitrosation in preterm labor.

We unambiguously identified 14 proteins that showed a statistically significant decrease in S-nitrosation in preterm labor samples exposed to S-nitrosation by GSNO. Area under the curve measures of extracted ion chromatograms and spectral counting showed that these proteins differ significantly in the preterm state of labor (Fig. 5, A–N). IPA identified nearest neighbor interactions with tumor necrosis factor (TNF), progesterone, and nitric oxide for 12 of these proteins and reveals an over representation of proteins involved in integrin signaling and cell morphology (Fig. 5O). Of particular interest is the disparate regulation of myosin light chain kinase (MYLK), which is a key regulator of the acto-myosin interaction and therefore smooth muscle contraction/relaxation dynamics (30). Disparate regulation of both MYLK and its smooth muscle target MYL9, the regulatory light chain, argues for a mechanistic role of S-nitrosation in the premature induction of labor.

Fig. 5.

Proteins involved in smooth muscle contraction showing a significant decrease in S-nitrosation during preterm labor. A and B: log2 relative expression of the AUC of extracted ion chromatograms. Bottom inset: identification of protein as well as any S-nitrosated peptides that were identified by LC/MS/MS. Top inset: gene identification, fold change, and P value for identified proteins. C-N: relative expression of normalized spectral counts of S-nitrosated protein (Normalized SC SNO) levels (left 3 bars of each graph) and total protein levels (right 3 bars of each graph) from experiment matched samples. *P < 0.05, when comparing NL and or L to PTL. †Signify no spectral counts were observed. O: Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of statistically significant decrease in S-nitrosated proteins (green) as well as their nearest connecting neighbors (yellow). TNF, tumor necrosis factor; ANXA6, annexin A6; VCL, vinculin; ACTN1, alpha-actinin 1; PDLIM1, PDZ and LIM domain protein 1; LGALS1, galectin-1; PALLD, Palladin; LPP, lipoma-preferred partner; PGR, progesterone receptor; CLIC1, chloride intracellular channel protein 1; ALB, serum albumin; MYLK, myosin light chain kinase, smooth muscle; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase P; HBB, hemoglobin subunit beta; HBD, hemoglobin subunit delta.

We wish to stress that the specific protein S-nitrosations that are decreased in pregnancy myometrium, when not the result of decreases in protein expression, are unexpected and underscore both the validity of our method of nitrosation and the likelihood that our data offer a window into the unique nature of preterm myometrium.

While there are contrasting data on whether or not NO synthases are present in myometrial smooth muscle cells, they need not be present in the cell for NO availability during gestation. In preterm labor we show downregulation of S-nitrosation in three of the known transporters of NO; serum albumin (ALB) known to be available to tissues by paracellular transport from blood (33), hemoglobin subunit-β (HBB), and hemoglobin subunit-δ (HBD) proteins likely derived from macrophages that are included in the microdissected muscle strips derived from myometrial biopsies (20). In conjunction with decreased S-nitrosation of glutathione S-transferase P (GSTP1), which has been shown to mediate NO storage and transport in cells (27), this could be caused by an alteration in the NO transport, storage, and signaling pathways leading to a decreased availability for the relaxing effects of NO in preterm labor.

Cytoskeletal and thin-filament regulation play a critical role in contraction/relaxation dynamics in smooth muscle tissues. Here we show that multiple proteins involved in regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics and thin-filament regulation are differentially S-nitrosated in preterm labor patients. Vinculin (VCL) and α-actinin (ACTN1), both implicated in the physical coupling of actin filaments to β-integrins and hence involved in providing a direct mechanical coupling between integrin proteins and the actin cytoskeleton (31), showed decreased S-nitrosation in preterm samples. VCL has also been shown to be recruited to the cell membrane during contractile stimulation and inhibition of this recruitment inhibits force development (31). Galectin-1 (LEG1), also known as LGALS1, is notably down S-nitrosated in preterm laboring tissues compared with nonlaboring tissues. LEG1 has been shown to interact with VCL at focal adhesions, and expression of LEG1 mRNA is upregulated by progesterone and downregulated by estrogen in uterine tissue (9) consistent with myometrial quiescence.

Chloride intracellular channel protein 1 (CLIC1), whhich can insert into intracellular membranes and form chloride ion channels, is a homologue of the glutathione S-transferase superfamily that is redox regulated (26) and has been shown to be strongly and reversibly inhibited by cytosolic F-actin (35). Both redox regulation as well as cytoskeletal interaction argue for a possible functional role during disparate states of redox controlled S-nitrosation of CLIC1. A definitive functional role for CLIC1 has not been determined in pregnancy, but our data argue for a plausible functional role in redox regulation during disparate states of pregnancy since CLC1 is down S-nitrosated in preterm labor.

Lipoma preferred partner (LPP) is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein located in focal adhesions and associates with the actin cytoskeleton (32). LPP can function as an adaptor protein that constitutes a platform that orchestrates protein-protein interactions. LPP was seen to be down S-nitrosated in preterm laboring tissue and has been shown to play an important role in the motility of smooth muscle cells (15). LPP is a mechanosensitive protein that is downregulated by stretch and apparently upregulated by blockade of nitric oxide synthase (19). This dependency argues for a role in the mechanoregulation of the continuously expanding myometrium in human pregnancy and could be further examined as a target biomarker for preterm labor. Considered together, these proteins constitute a potential interactome and discovering their behavior as S-nitrosated proteins may further our understanding of contraction-relaxation signaling in myometrium.

Conclusion.

The induction of labor in humans is a complex problem that will require multiple approaches to understand how to control and manipulate the process. There are no such approaches at present as evidenced by the lack of Food and Drug Administration-approved tocolytics available for preterm labor. What obstetricians provide now in the United States is off-label and ineffective at delaying delivery until term (16). The standard approach to preterm labor has been the adoption of established treatments for other medical conditions involving smooth muscle tissue and their application to women in labor too soon (3). To generate an opportunity to approach the problem of preterm labor that is unique to myometrial biochemistry, we provide here an NO-mediated “fingerprint” of posttranslationally modified proteins integral to relaxation mechanisms that will allow directed research regarding the regulation of quiescence of the uterus during gestation. The identification of S-nitrosated proteins in the myometrium provides a platform from which to explore new and improved hypotheses for future research by establishing a unique snapshot of how NO modifications are disparately changing in the preterm labor state. The aberrant preterm labor S-nitrosoproteome fingerprint (Fig. 3) provides us with multiple novel targets and putative biomarkers to help elucidate the disparate mechanisms involved in the premature induction of labor. Of particular interest to us is the difference in S-nitrosation of the key known regulators of smooth muscle contraction in preterm labor samples, such as MYLK, MYL9, and PFN1. The functional role of this disparity has yet to be elucidated, but we show convincing evidence that these proteins are regulated very differently by NO at the protein level independent of protein abundance.

GRANTS

Our research is supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD-053028, March of Dimes Prematurity Initiative Grant 21-FY10-176, and a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (to I. L. O. Buxton). The IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence Grant P20-RR-016464 and National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant 8 P20-GM-103440-11 supported the Nevada Proteomics Center and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (PhRMA) supported C. Ulrich with a Predoctoral Fellowship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.U. and I.L.O.B. conception and design of research; C.U. and D.R.Q. performed experiments; C.U., D.R.Q., K.S., and I.L.O.B. analyzed data; C.U., K.S., and I.L.O.B. interpreted results of experiments; C.U. prepared figures; C.U. edited and revised manuscript; C.U., D.R.Q., K.S., and I.L.O.B. approved final version of manuscript; I.L.O.B. drafted manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sara Thompson for collecting patient samples and Scott Barnett for technical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur ND, Orlando R, Weatherly B, Atwood J. Precursor Intensity Label-Free Quantification of Standard Peptide Mixtures Using ProteoIQ (Online). http://premierbiosoft.com/protein_quantification_software/features/features.html [26 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman RE, Butler AS. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton IL. Regulation of uterine function: a biochemical conundrum in the regulation of smooth muscle relaxation. Mol Pharmacol 65: 1051–1059, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buxton IL, Crow W, Mathew SO. Regulation of uterine contraction: mechanisms in preterm labor. AACN Clin Issues 11: 271–282, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buxton IL, Kaiser RA, Malmquist NA, Tichenor S. NO-induced relaxation of labouring and non-labouring human myometrium is not mediated by cyclic GMP. Br J Pharmacol 134: 206–214, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buxton IL, Milton D, Barnett SD, Tichenor SD. Agonist-specific compartmentation of cGMP action in myometrium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335: 256–263, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmichael JD, Winder SJ, Walsh MP, Kargacin GJ. Calponin and smooth muscle regulation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 1415–1419, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choe YS, Shim C, Choi D, Lee CS, Lee KK, Kim K. Expression of galectin-1 mRNA in the mouse uterus is under the control of ovarian steroids during blastocyst implantation. Mol Reprod Dev 48: 261–266, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleeter MW, Cooper JM, Darley-Usmar VM, Moncada S, Schapira AH. Reversible inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, by nitric oxide. Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS Lett 345: 50–54, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalle-Donne I, Milzani A, Giustarini D, Di Simplicio P, Colombo R, Rossi R. S-NO-actin: S-nitrosylation kinetics and the effect on isolated vascular smooth muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 21: 171–181, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evangelista AM, Rao VS, Filo AR, Marozkina NV, Doctor A, Jones DR, Gaston B, Guilford WH. Direct regulation of striated muscle myosins by nitric oxide and endogenous nitrosothiols. PLoS One 5: e11209, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulep E, Vedernikov Y, Saade GR, Garfield RE. Contractility of late pregnant rat myometrium is refractory to activation of soluble but not particulate guanylate cyclase. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185: 158–162, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson A, Babbedge R, Brave SR, Hart SL, Hobbs AJ, Tucker JF, Wallace P, Moore PK. An investigation of some S-nitrosothiols, and of hydroxy-arginine, on the mouse anococcygeus. Br J Pharamcol 107: 715–721, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorenne I, Nakamoto RK, Phelps CP, Beckerle MC, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. LPP, a LIM protein highly expressed in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C674–C685, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas DM, Caldwell DM, Kirkpatrick P, McIntosh JJ, Welton NJ. Tocolytic therapy for preterm delivery: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 345: e6226, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han M, Dong LH, Zheng B, Shi JH, Wen JK, Cheng Y. Smooth muscle 22 alpha maintains the differentiated phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells by inducing filamentous actin bundling. Life Sci 84: 394–401, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 150–166, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooper CL, Dash PR, Boateng SY. Lipoma preferred partner is a mechanosensitive protein regulated by nitric oxide in the heart. FEBS Open Bio 2: 135–144, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanisevic M, Segerer S, Rieger L, Kapp M, Dietl J, Kammerer U, Frambach T. Antigen-presenting cells in pregnant and non-pregnant human myometrium. Am J Reprod Immunol 64: 188–196, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffrey SR, Snyder SH. The biotin switch method for the detection of S-nitrosylated proteins. Sci STKE 2001: pl1, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Je HD, Sohn UD. SM22alpha is required for agonist-induced regulation of contractility: evidence from SM22alpha knockout mice. Mol Cells 23: 175–181, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem 74: 5383–5392, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirsch M, Buscher AM, Aker S, Schulz R, de Groot H. New insights into the S-nitrosothiol-ascorbate reaction. The formation of nitroxyl. Org Biomol Chem 7: 1954–1962, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuenzli KA, Bradley ME, Buxton IL. Cyclic GMP-independent effects of nitric oxide on guinea-pig uterine contractility. Br J Pharmacol 119: 737–743, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littler DR, Harrop SJ, Fairlie WD, Brown LJ, Pankhurst GJ, Pankhurst S, DeMaere MZ, Campbell TJ, Bauskin AR, Tonini R, Mazzanti M, Breit SN, Curmi PM. The intracellular chloride ion channel protein CLIC1 undergoes a redox-controlled structural transition. J Biol Chem 279: 9298–9305, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lok HC, Suryo Rahmanto Y, Hawkins CL, Kalinowski DS, Morrow CS, Townsend AJ, Ponka P, Richardson DR. Nitric oxide storage and transport in cells are mediated by glutathione S-transferase P1–1 and multidrug resistance protein 1 via dinitrosyl iron complexes. J Biol Chem 287: 607–618, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mezgueldi M, Mendre C, Calas B, Kassab R, Fattoum A. Characterization of the regulatory domain of gizzard calponin. Interactions of the 145–163 region with F-actin, calcium-binding proteins, and tropomyosin. J Biol Chem 270: 8867–8876, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 75: 4646–4658, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okagaki T, Hayakawa K, Samizo K, Kohama K. Inhibition of the ATP-dependent interaction of actin and myosin by the catalytic domain of the myosin light chain kinase of smooth muscle: possible involvement in smooth muscle relaxation. J Biochem 125: 619–626, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Opazo Saez A, Zhang W, Wu Y, Turner CE, Tang DD, Gunst SJ. Tension development during contractile stimulation of smooth muscle requires recruitment of paxillin and vinculin to the membrane. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C433–C447, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petit MM, Fradelizi J, Golsteyn RM, Ayoubi TA, Menichi B, Louvard D, Van de Ven WJ, Friederich E. LPP, an actin cytoskeleton protein related to zyxin, harbors a nuclear export signal and transcriptional activation capacity. Mol Biol Cell 11: 117–129, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnitzer JE, Oh P. Albondin-mediated capillary permeability to albumin. Differential role of receptors in endothelial transcytosis and endocytosis of native and modified albumins. J Biol Chem 269: 6072–6082, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shynlova O, Nedd-Roderique T, Li Y, Dorogin A, Lye SJ. Myometrial immune cells contribute to term parturition, preterm labour and post-partum involution in mice. J Cell Mol Med 17: 90–102, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh H, Cousin MA, Ashley RH. Functional reconstitution of mammalian “chloride intracellular channels” CLIC1, CLIC4 and CLIC5 reveals differential regulation by cytoskeletal actin. FEBS J 274: 6306–6316, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith BC, Marletta MA. Mechanisms of S-nitrosothiol formation and selectivity in nitric oxide signaling. Curr Opin Chem Biol 16: 498–506, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki T, Mori C, Yoshikawa H, Miyazaki Y, Kansaku N, Tanaka K, Morita H, Takizawa T. Changes in nitric oxide production levels and expression of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the rat uterus during pregnancy. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 73: 2163–2166, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang DD. Intermediate filaments in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C869–C878, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulrich C, Quillici DR, Schegg K, Woolsey R, Nordmeier A, Buxton IL. Uterine smooth muscle S-nitrosylproteome in pregnancy. Mol Pharmacol 81: 143–153, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdes G, Corthorn J. Review: the angiogenic and vasodilatory utero-placental network. Placenta 32, Suppl 2: S170–175, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vedernikov YP, Syal AS, Okawa T, Jain V, Saade GR, Garfield RE. The role of cyclic nucleotides in the spontaneous contractility and responsiveness to nitric oxide of the rat uterus at midgestation and term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182: 612–619, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vizcaino JA, Cote RG, Csordas A, Dianes JA, Fabregat A, Foster JM, Griss J, Alpi E, Birim M, Contell J, O'Kelly G, Schoenegger A, Ovelleiro D, Perez-Riverol Y, Reisinger F, Rios D, Wang R, Hermjakob H. The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D1063–1069, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winder SJ, Allen BG, Clement-Chomienne O, Walsh MP. Regulation of smooth muscle actin-myosin interaction and force by calponin. Acta Physiol Scand 164: 415–426, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yellon SM, Mackler AM, Kirby MA. The role of leukocyte traffic and activation in parturition. J Soc Gynecol Investig 10: 323–338, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.