Abstract

Objective. Little is known about the association between gout and socioeconomic status (SES). Inequalities in rheumatology provision associated with SES may need to be addressed by health care planners. The aim of this study is to investigate the association of gout and SES in the community at both the individual and area levels.

Methods. Questionnaires were sent to all patients older than age 50 years who were registered with eight general practices in North Staffordshire. Data on individual SES were collected by questionnaire while area SES was measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation derived from respondents’ postcodes. Responders reported their occupation, education and the adequacy of their income; their medical records were searched for consultations for gout.

Results. Of the 348 consultations for gout in this period, at the individual level there was a significant association between gout and income. An association of gout with education was seen only in the unadjusted analyses. No association was found between gout and area level deprivation.

Conclusion. Gout is associated with some aspects of individual level but not area level deprivation. More extensive musculoskeletal services may need to be provided in low income areas, although further research is needed.

Keywords: gout, primary care, observational study, consultation data, questionnaires socioeconomic status

Introduction

Knowledge of the socioeconomic status (SES) of a community is of great importance when planning health services, as deprivation is a proven risk factor for increased consultation, increased morbidity and an increase in all-cause mortality [1, 2]. Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis, affecting 1.4% of adults in the UK, and is predominantly managed in general practice [3].

Little is known about the association of gout with SES, although the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis and the functional outcome of inflammatory polyarthritis have both been shown to be significantly related to deprivation [4, 5]. Should such associations between gout and SES exist, changes to the provision of musculoskeletal services may be warranted.

One previous study found an inverse relationship between the prevalence of gout and poor SES, defined using occupation, in England [6]. In Maori populations in New Zealand, an increase in the prevalence of gout has been reported with increasing deprivation [7]. In a US in-patient survey, gout was shown to be associated with being African American and having a low income [8]. However, the findings of these latter two studies may not be generalizable to people with gout in the UK.

Nothing appears to be known of the association between gout and area level indicators as opposed to individual level indicators of SES. Several studies in other diseases have found that the relationship of morbidity and mortality to individual and area level deprivation is not straightforward and may vary between different age groups, genders, nationalities and with SES in childhood [2, 9–11]. Individual level data, often obtained through questionnaires, is time consuming and may show individual variation within an area, whereas area level data may be more readily obtained from census data. The objective of this study was to investigate the association between gout and SES in the community at both the individual and area level using both patient questionnaires and general practice consultation data.

Methods

Study population

The study used data from a prospective population-based cohort study, the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP) [12]. Participants age 50 years and older who were registered in eight general practices in North Staffordshire were mailed a baseline questionnaire that collected information on pain and disability as well as sociodemographic and lifestyle information. Participants responding to the baseline questionnaire were asked for consent to review their electronic medical records. The eight participating general practices are members of the Keele GP Research Partnership [13]. Ethical approval was obtained from the North Staffordshire Local Research Ethics Committee.

Identification of patients with gout

Individuals were defined as having gout if they had a consultation for gout in the 2 years before or after their baseline questionnaire by review of their medical records. Consultations with a GP are recorded using the hierarchical Read code system of morbidity, which is used in the UK and can be mapped to ICD-10 codes (e.g. ..C34 Gout). This allows consultations for gout to be readily identified from the primary care records for participants who responded to the baseline survey. A list of the Read codes used to define gout is available from the authors. For the purposes of this study, patients are recorded as not having gout if they did not consult their GP about gout in the 4-year study period.

Deprivation measures

Area level

The English Index of Multiple Deprivation 2004 (IMD) score measures levels of deprivation in geographical areas in England known as lower super output areas (LSOAs). There are 32 482 such geographical areas with a mean of 1500 people in each. The IMD score ranks areas, with a rank of 1 being the most deprived area. The IMD score is based on seven domains, weighted as follows: income (22.5%), employment (22.5%), health deprivation and disability (13.5%), education, skills and training (13.5%), barriers to housing and services (9.3%), living environment (9.3%) and crime (9.3%). For this study, IMD ranks were split into quintiles of neighbourhood deprivation, with quintile 1 having the lowest level of neighbourhood deprivation and 5 the highest.

Individual level

Three measures of individual level deprivation were used in this study. All were self-reported in the baseline questionnaire. First, occupational class was classified according to the participant’s self-reported current occupation or most recent occupation if not currently employed. Occupational class was based on the 2002 National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) categorization, which was further categorized into three occupational class groups: (i) managerial/professional/intermediate (non-manual); (ii) self-employed and (iii) lower supervisory/lower technical/semi-routine/routine occupations (manual). Second, the individual reported whether he or she attended further education after leaving school. Third, participants were asked how the cost of living affects them. Participants were classed as having an adequate income if they had responded quite comfortably off or able to manage, or were classed as having an inadequate income if they responded that they find it a strain to get by from week to week or have to be careful with money. Perceived adequacy of income has been shown to be strongly associated with both household income and educational level [14].

Potential confounding factors

Age, gender, BMI (recorded as <25, normal weight; 25–30, overweight; 30+, obese) and alcohol consumption (recorded as daily or most days, once or twice a week, once or twice a month, once or twice a year, never) from the self-reported questionnaire and the GP were adjusted for in the analysis as potential confounding factors.

Analysis

Differences in demographic variables between participants with and without gout were examined using the chi-squared test and t-test as appropriate. The association between demographic variables and having gout was assessed using unadjusted odds ratios (ORs). Random intercept logistic multilevel models were used to account for the clustering of individuals within LSOAs.

Models were adjusted for age, gender, neighbourhood deprivation, the three individual measures of deprivation and the confounding factors. Results were reported as ORs with 95% CIs.

Cross-level interactions between individual level deprivation measures and area level neighbourhood deprivation were added to the model when these covariates were statistically significant (P < 0.05) which, would show the association between gout and individual level deprivation measures varied between different deprivation groups. The results are presented as ORs with 95% CIs. Analysis was performed in MLwiN v 2.25 [15].

Results

Response

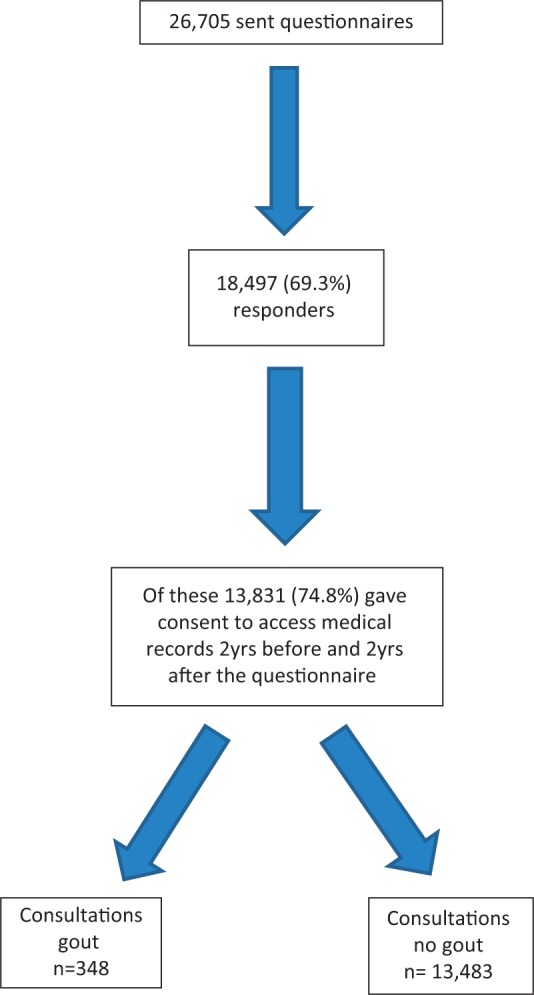

A total of 13 831 participants responded to the baseline survey and provided consent for their medical records to be reviewed (Fig. 1). The mean age was 65.9 (10.1 s.d.) years and 7401 (53.5%) respondents were female. Responders were more likely to be female. Non-response was evenly distributed across all age groups in females, whereas non-response in males was more marked in the youngest category (50–59 years).

Fig. 1.

Numbers of persons responding to the questionnaire and consenting to a medical records search.

The respondents came from 253 LSOAs. Of those who had complete data on the extent of education and occupational class, 489 of 7608 participants (6.4%) with manual occupations had received further education, in contrast to 1051 of 4061 participants (25.9%) with non-manual occupations. There was a significant association between neighbourhood deprivation and occupational class (P < 0.001). Of the participants living in the most deprived areas, 2061 (76.9%) had manual occupations and 473 (17.7%) had non-manual occupations, whereas of participants living in the least deprived areas, 1155 (46.7%) had manual occupations and 1149 (46.4%) had non-manual occupations; 43.2% of the respondents described their income as inadequate.

Gout consultation

During the 4-year period, 348 (2.5%) participants had a record of gout. Participants with gout were older than those without gout [68.8 (s.d. 9.6) vs 65.9 (s.d. 10.1) years]. Of the 348 people with gout, 252 (72.4%) were males.

In unadjusted analyses, gout was less common in those who had attended further education (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44, 0.95) and more common in those with inadequate income (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.11, 1.71). However, occupational class and IMD quintiles were not associated with gout (Table 1). The variance partition coefficient from the null model was 1.18 × 10−17, therefore gout did not vary between the five neighbourhood deprivation groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics, SES, obesity and alcohol use between those with gout and those without gout

| Variable | Consultation for gout, n (%) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| n = 13483 (97.5) | n = 348 (2.5) | |||

| Age at baselineb, mean (s.d.), years | 65.8 (10.1) | 68.8 (9.6) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.05 (1.03, 1.06) |

| Genderb | ||||

| Female | 7305 (98.7) | 96 (1.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 6178 (96.1) | 252 (3.9) | 3.10 (2.45, 3.94) | 3.05 (2.31, 4.03) |

| Neighbourhood deprivation | ||||

| Least deprived | 2591 (97.6) | 65 (2.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Second least deprived | 2660 (97.8) | 59 (2.2) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.26) | 0.75 (0.48, 1.15) |

| Mid-deprived | 2830 (97.1) | 85 (2.9) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.66) | 1.08 (0.73, 1.60) |

| Second most deprived | 2543 (97.6) | 62 (2.4) | 0.97 (0.68, 1.38) | 0.70 (0.45, 1.10) |

| Most deprived | 2855 (97.4) | 77 (2.6) | 1.08 (0.77, 1.50) | 0.77 (0.49, 1.22) |

| Occupational class | ||||

| Non-manual | 4022 (97.5) | 104 (2.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-employed | 830 (97.5) | 21 (2.5) | 0.98 (0.61, 1.57) | 0.67 (0.40, 1.12) |

| Manual | 7589 (97.4) | 200 (2.6) | 1.02 (0.80, 1.30) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.33) |

| Educationb | ||||

| School-age education | 11527 (97.4) | 312 (2.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Further education | 1660 (98.3) | 29 (1.7) | 0.65 (0.44, 0.95) | 0.86 (0.56, 1.32) |

| Perceived adequacy of incomeb | ||||

| Adequate income | 7532 (97.8) | 166 (2.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Inadequate income | 5684 (97.1) | 173 (2.90) | 1.38 (1.11, 1.71) | 1.44 (1.13, 1.84) |

| BMIb | ||||

| Normal | 5158 (98.4) | 84 (1.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Overweight | 5381 (97.2) | 158 (2.9) | 1.80 (1.38, 2.36) | 1.66 (1.24, 2.22) |

| Obese | 2416 (96.5) | 88 (3.5) | 2.24 (1.65, 3.03) | 2.99 (2.15, 4.17) |

| Alcohol consumptionb | ||||

| Daily | 2760 (96.5) | 99 (3.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–2 weeks | 4685 (97.4) | 125 (2.6) | 0.74 (0.57, 0.97) | 0.78 (0.58, 1.04) |

| 1–2 months | 2082 (98.0) | 42 (2.0) | 0.56 (0.39, 0.81) | 0.63 (0.42, 0.93) |

| 1–2 years | 2190 (98.2) | 41 (1.8) | 0.52 (0.36, 0.75) | 0.54 (0.36, 0.83) |

| Never | 1609 (97.9) | 34 (2.1) | 0.59 (0.40, 0.87) | 0.49 (0.30, 0.80) |

aEstimates are adjusted for general practice.

bThe chi-square test (or t-test for age) was statistically significant at the 5% level.

After adjustment for potential confounders, only inadequacy of income remained significantly associated with gout (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13, 1.84) (Table 1). Cross-level interaction terms between the individual and area level deprivation measures were not added to the model.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the potential association between individual and area level deprivation and gout in the UK. By linking the findings of a large population-based questionnaire with electronic medical records we have been able to describe an association between gout and inadequate income. No association was found between gout and area level deprivation. Of the three markers of individual variation, there was a significant association between gout and both a lack of further education and inadequate income, but only the association with poor income remained after adjustment for confounding variables.

There are few community-based studies of gout and SES. We did not find an association between gout and low SES defined by occupation, in contrast to the previous study by Gardner et al. [6]. A study of a Maori population in New Zealand used a methodology similar to ours, finding that gout was associated with poor SES, including low income, but also receipt of means-tested benefits, lack of qualifications, single-parent families, and overcrowding [7]. We were unable to assess the previous observation that gout is more common in certain racial groups due to the low prevalence of ethnic minority groups in North Staffordshire [8].

All the practices in this study belong to the Keele GP Research Partnership. These practices undergo regular training and assessment to ensure that their coding of consultations meets the highest standards [16]. A strength of this study is the high response rate to the questionnaire of 69.3%. The study was undertaken in primary care, where most people with gout are managed.

This study was carried out in an area of England where socioeconomic deprivation is higher than the national average, with educational attainment and income being below both regional and national levels. This may affect the generalizability of the results in both the UK and internationally.

This analysis was undertaken in the NorStOP dataset, which includes only adults ages 50 years and older. Consequently the participants’ mean age was above the usual UK retirement age of 65 years, which could possibly have influenced the perceived adequacy of income or area level deprivation, but not occupational class or attendance at further education. Accordingly our findings may not be generalizable to younger people with gout. Although response to the questionnaire was similar in males and females and did not differ by age among females, there was selective non-response in the youngest age group in males, which could possibly have influenced our findings, as this age group is of working age. Deprivation data were not available for non-responders, so we were unable to assess selective non-response by SES.

The link between poor health and deprivation appears to be established, but is not always straightforward [2, 17]. This may affect the ability to generalize from our findings, although the adequacy of income was significantly lower in the group with gout compared to those without gout. A further limitation could be the use of a general practice diagnosis of gout, which is usually made only on clinical grounds. However, we have previously examined the validity of the gout diagnosis recorded in general practice consultations, finding the recording of clinical features generally consistent with gout [18].

The association between gout and low income suggests that neighbourhoods including greater numbers of lower income compared with more affluent households may need the provision of more health services, including musculoskeletal services. This accords with previous observations that the provision of health services is reduced in areas of lower compared to higher occupational class [18].

This study needs to be repeated using a larger general practice database that will allow more detailed analysis. Information is lacking concerning many musculoskeletal diseases and their association with SES.

When considering the provision of medical services, gout should not be considered in isolation. Gout is closely associated with the cardiovascular risk factors making up the metabolic syndrome that includes diabetes, obesity and ischaemic heart disease [19]. The metabolic syndrome itself is associated with deprivation [20]. Our findings suggest that gout should be incorporated into multi-morbidity reviews in primary care in lower income areas.

Rheumatology key messages.

Associations between gout and individual and area level SES were determined in primary care.

In this observational study in general practice, gout is associated with inadequate income.

When planning rheumatology services for gout and other inflammatory arthropathies, health planners need to consider greater provision in deprived areas.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baker D, Mead N, Campbell S. Inequalities in morbidity and consulting behaviour for socially vulnerable groups. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:124–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe DH, Eisenbach Z, Neumark YD, et al. Individual, household and neighbourhood socioeconomic status and mortality: a study of absolute and relative deprivation. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:989–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M, et al. Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:960–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, Klareskog L, et al. 2005, Socioeconomic status and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1588–94. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.031666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison MJ, Farragher T, Clarke AM, et al. Association of functional outcome with both personal- and area-level socioeconomic inequalities in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1297–304. doi: 10.1002/art.24830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner MJ, Power C, Barker DJP, et al. The prevalence of gout in three English towns. Int J Epidemiol. 1982;11:71–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/11.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor W, Smeets L, Hall J, et al. The burden of rheumatic disorders in general practice: consultation rates for rheumatic disease and the relationship to age, ethnicity, and small-area deprivation. N Z Med J. 2004;117:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelber AC, Maynard JW, Haywood C., Jr The association of race with gout: a broadly representative inpatient survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(Suppl. 10):1565. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkleby M, Cubbin C, Ahn D. Effect of cross-level interaction between individual and neighbourhood socioeconomic status on adult mortality rates. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2145–53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundquist K, Malmström M, Johansson SE. Neighbourhood deprivation and incidence of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study of 2.6 million women and men in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:71–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.58.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawlor D, Sterne J, Tynelius P, et al. Association of childhood socioeconomic position with cause-specific mortality in a prospective record linkage study of 1,839,384 individuals. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:907–15. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, et al. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: a cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP) Pain. 2004;110:361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G, et al. Social risks for disabling pain in older people: a prospective study of individual and area characteristics. Pain. 2008;137:652–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litwin H, Sapir E. Perceived income adequacy among older adults in 12 countries: findings from the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. Gerontologist. 2009;49:397–406. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rasbash J, Charlton C, Browne WJ et al. (2005) MLwiN Version 2.02. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, UK, 2005.

- 16.Porcheret M, Hughes R, Evans D, et al. Data quality of general practice electronic health records: the impact of a program of assessments, feedback and training. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:78–86. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart T. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1:405–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roddy E, Mallen CD, Hider SL, et al. Prescription and comorbidity screening following consultation for acute gout in primary care. Rheumatology. 2010;49:105–11. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:109–15. doi: 10.1002/art.22466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salsberry PJ, Corwin E, Reagan PB. A complex web of risks metabolic syndrome: race/ethnicity, economics, and gender. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]