Abstract

Rice grassy stunt virus (RGSV) is a serious threat to rice production in Southeast Asia. RGSV is a member of the genus Tenuivirus, and it induces leaf yellowing, stunting, and excess tillering on rice plants. Here we examined gene responses of rice to RGSV infection to gain insight into the gene responses which might be associated with the disease symptoms. The results indicated that (1) many genes related to cell wall synthesis and chlorophyll synthesis were predominantly suppressed by RGSV infection; (2) RGSV infection induced genes associated with tillering process; (3) RGSV activated genes involved in inactivation of gibberellic acid and indole-3-acetic acid; and (4) the genes for strigolactone signaling were suppressed by RGSV. These results suggest that these gene responses to RGSV infection account for the excess tillering specific to RGSV infection as well as other symptoms by RGSV, such as stunting and leaf chlorosis.

Keywords: Rice grassy stunt virus, plant hormone, stunting, tillering, transcriptome analysis

Introduction

Grassy stunt disease of rice caused by Rice grassy stunt virus (RGSV) is one of the severe virus diseases of rice in several Southeast Asian countries (Shikata et al., 1980; Ramirez, 2008). RGSV is a member of the genus Tenuivirus, and is transmitted by brown planthopper (BPH, Nilaparvata lugens) and by two other Nilaparvata spp. (Hibino, 1996). RGSV has a thin filamentous-shaped virion, and the genome is composed of six ambisense single-stranded RNA segments (RNA1—6) containing 12 open reading frames (Ramirez, 2008). RGSV RNA 1, 2, 5, and 6 correspond to the four RNA segments of the type member of Tenuivirus, Rice stripe virus (RSV). RGSV RNA 3 and 4 are unique in this genus. The phylogenic relationship among tenuiviruses, including RGSV and RSV, indicates that RGSV forms a group distinct from the other tenuiviruses (Ramirez, 2008). Typical symptoms induced by RGSV infection are leaf yellowing (chlorosis), stunting, and excess tillering (branching) (Shikata et al., 1980). Chlorosis and stunting are also observed in plants infected with other tenuiviruses, whereas excess tillering is a symptom specific to RGSV infection.

Plant disease symptoms caused by virus infection are accompanied by changes in the expression of the genes involved in morphogenesis and development (Dardick, 2007; Lu et al., 2012; Pierce and Rey, 2013). Thus, common and specific symptoms might be associated with common and specific responses of morphogenesis- and development-related genes (Dardick, 2007). Nicotiana benthamiana infected with either Plum pox virus (PPV) or Tomato ring spot virus (ToRSV) showed leaf chlorosis, implying that chloroplast functions might have been impaired by infection with the viruses (Dardick, 2007). Transcriptome analysis of PPV- and ToRSV-infected plants showed the suppression of genes functioning in chloroplasts, however, the genes encoding ribosomal protein functioning in chloroplasts were suppressed only in ToRSV-infected plants (Dardick, 2007). These results indicate that similarity in disease symptoms may not result from the similarity in gene responses to virus infection, and that the gene responses associated with particular symptoms may depend on the virus species.

In this study, we analyzed the gene expression profile in rice plants infected with RGSV to gain insight into RGSV-induced gene responses associated with the symptoms. The results suggested that symptoms such as stunting and leaf chlorosis caused by RGSV infection were associated with the suppression of genes related to cell wall, hormone synthesis and chlorophyll synthesis while excess tillering specific to RGSV infection is associated with the suppression of strigolactone signaling and GA metabolism.

Materials and methods

Virus, insect vector, and plant samples

RGSV was maintained in rice plants (Oryza sativa cv. Nipponbare) in an air-conditioned greenhouse (25–30°C) (Shimizu et al., 2013). One hundred rice seeds were sown in a pot (250 mm in diameter and 100 mm in height) that had been filled with commercial soil mixture (Bonsol; Sumitomo Chemical, Japan). Twelve-day-old rice seedlings were exposed to ~300 viruliferous or virus-free BPH (for mock inoculation) in an inoculation chamber (340 mm wide by 260 mm deep by 340 mm high) for 1 day. Forty-two inoculated plants were transplanted and grown in a plastic container (53 cm wide by 35 cm deep by 10 cm high) in the greenhouse. At 28 days post-inoculation (DPI), when disease symptoms such as stunting and leaf yellowing became evident, two newly developed leaves from each plant which exhibited disease symptoms were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Sample preparations were independently repeated three times for microarray experiments. Infection with RGSV in plants was evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using an antiserum against RGSV.

Microarray experiment and data analysis

Total RNA was extracted from leaf samples pooled from five independent RGSV-infected or mock-inoculated plants by the RNeasy Maxi kit (Qiagen, UK). A microarray experiment involving complementary RNA synthesis, hybridization, array scanning, and image processing was performed as described previously (Satoh et al., 2010). A gene was declared “expressed” if the average signal intensity of the gene was higher than 64 in plants. A significantly differentially expressed gene (DEG) between RGSV-infected and mock-inoculated plants was defined as an expressed gene with (1) a signal intensity ratio between RGSV-infected and mock-inoculated samples greater than 1.5, and (2) significant changes in gene expression between two plants (P ≤ 0.05 by a paired t-test; permutation: all; false discovery rate correction: adjusted Bonferroni method). The gene expression profile of RGSV-infected plant (data series GSE 25217 available at NCBI GEO, Supplementary Material 1) was analyzed by a 4 × 44 K microarray system (platform number GPL7252 available at NCBI-GEO) (Edgar et al., 2002). All data are Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAME) compliant.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments for transcripts of selected rice genes were synthesized using 1.0 μg of total RNA with 50 ng/μL of random hexamer primers by SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). The resultant reaction mixtures containing cDNA were diluted four times. Four μL of diluted mixture was used for PCR. Primers for selected rice genes are shown in Supplementary Material 2. The cycling program was initial denaturation for 2 min at 95°C, followed by 30–40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 15 s at variable annealing temperatures, and 45 s at 68°C, with a final extension of 1 min at 68°C. Annealing temperature was adjusted depending on the Tm of designed primers, and was between 50 and 60°C.

Quantification of strigolactone

RGSV-infected and mock-inoculated rice plants were prepared as described previously and grown for 6 weeks. Then, the plants (n = 20) were transferred to 1 L 1/2 Hoagland hydroponic culture medium without phosfate. After 2 days of acclimatization, culture media were collected and extracted three times with an equal volume of ethyl acetate containing 2′-epi-5-deoxystrigol-d6 (200 pg) as an internal standard. The ethyl acetate solutions were combined, washed with 0.2 M K2HPO4 (pH 8.3), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to produce crude root exudate samples. Crude samples dissolved with 1 mL 90% (v/v) ethyl acetate/hexane were passed through Sep-pack silica cartridges. The eluents were concentrated in vacuo and the residues were taken up with a small volume of acetonitrile for liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)/MS analyses. Quantification of 2′-epi-5-deoxystrigol was conducted by LC-MS/MS as described previously (Yoneyama et al., 2011).

Results

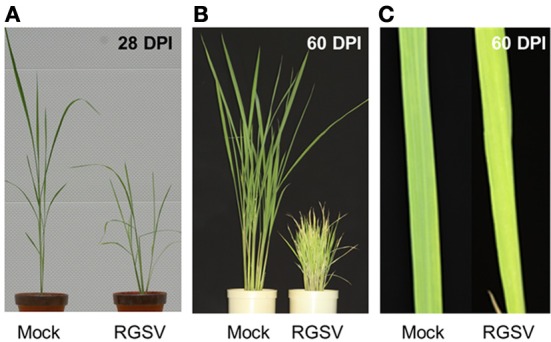

Disease symptoms caused by RGSV infection

Rice plants infected with RGSV showed disease symptoms such as excessive tillering, stunting, and leaf yellowing. The symptoms became more severe after 28 DPI (Figure 1A). Profuse tillering became more evident in the RGSV-infected plants at 60 DPI (Figure 1B). The RGSV-infected plant was much shorter than the mock-inoculated plants at 60 DPI (Figure 1B). Leaf yellowing by RGSV infection was also more severe at 60 DPI (Figures 1B,C) than at 28 DPI (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Symptoms in rice caused by RGSV infection. (A) Rice plants at 28 days and (B) 60 days after RSGV inoculation and mock inoculation. (C) Leaf yellowing of RGSV-infected plants at 60 days after inoculation.

Transcriptome responses of rice to RGSV infection

Changes in gene expression caused by RGSV infection were examined by direct comparison between RGSV- and mock-inoculated rice plants at 28 DPI. The numbers of expressed genes and DEGs were 24,911 and 8203, respectively (Table 1, Supplementary Material 1). The expression patterns of some DEGs were confirmed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Supplementary Material 2).

Table 1.

Numbers of DEGs in gene ontology groups overrepresented or underrepresented in RGSV-infected plants.

| Categories | Cene ontology ID1 | Gene ontology terma | Number of expressed genes | Number of DEGb | P-valuec | Response of DEG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced | Suppressed | ||||||

| Component | GO:0016020 | Membrane | 3193 | 1188 | 2.53E-05 | 671 | 517 |

| GO:0005618 | Cell wall | 1645 | 688 | 3.25E-10 | 377 | 311 | |

| GO:0005623 | Cell | 233 | 100 | 7.88E-03 | 54 | 46 | |

| GO:0005622 | Intracellular | 627 | 152 | 1.50E-04 | 103 | 49 | |

| GO:0005840 | Ribosome | 301 | 43 | 1.73E-08 | 18 | 25 | |

| GO:0005829 | Cytosol | 264 | 56 | 9.08E-04 | 33 | 23 | |

| Process | GO:0009719 | Response to endogenous stimulus | 2619 | 1072 | 9.56E-13 | 615 | 457 |

| GO:0007582 | Physiological process | 2105 | 836 | 5.78E-08 | 499 | 337 | |

| GO:0007165 | Signal transduction | 2022 | 785 | 3.87E-06 | 485 | 300 | |

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 1804 | 694 | 4.11E-05 | 411 | 283 | |

| GO:0009628 | Response to abiotic stimulus | 1527 | 676 | 1.14E-14 | 404 | 272 | |

| GO:0008150 | Biological process | 1388 | 586 | 1.63E-09 | 357 | 229 | |

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 1348 | 585 | 2.12E-11 | 321 | 264 | |

| GO:0009058 | Biosynthetic process | 1222 | 492 | 7.94E-06 | 214 | 278 | |

| GO:0006519 | Amino acid and derivative metabolic process | 803 | 331 | 4.23E-05 | 152 | 179 | |

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 659 | 317 | 1.14E-11 | 133 | 184 | |

| GO:0006629 | Lipid metabolic process | 655 | 272 | 1.26E-04 | 132 | 140 | |

| GO:0006118 | Electron transport | 481 | 210 | 4.12E-05 | 98 | 112 | |

| GO: 0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 473 | 226 | 1.82E-08 | 107 | 119 | |

| GO: 0007275 | Multicellular organismal development | 463 | 205 | 2.09E-05 | 128 | 77 | |

| GO:0030154 | Cell differentiation | 426 | 183 | 3.10E-04 | 120 | 63 | |

| GO:0009908 | Flower development | 342 | 164 | 1.29E-06 | 92 | 72 | |

| GO: 00096 53 | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | 204 | 95 | 6.87E-04 | 61 | 34 | |

| GO:0016043 | Cellular component organization and biogenesis | 784 | 196 | 1.09E-04 | 117 | 79 | |

| GO:0006412 | Translation | 516 | 83 | 2.60E-11 | 39 | 44 | |

| GO:0006139 | Nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolic process | 453 | 95 | 9.20E-06 | 59 | 36 | |

| 24911 | 8204 | 3896 | 4307 | ||||

Based on Rice Genome Annotation Project database Osa1 (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu).

Numbers in bold (or underlined) text indicate that the corresponding ontology groups are overrepresented (or underrepresented) based on a χ2-test between the actual ratio of DEG (the number of DEGs/the number of expressed genes belonging to the corresponding ontology group) and the expected ratio of DEG [the number of total DEGs (8204)/the number of the total expressed genes (24,911)].

From the χ2-test.

We classified the DEGs in RGSV-infected plants according to gene ontology. For many ontology categories, the ratio of the number of DEGs to the number of expressed genes was significantly higher (P < 0.01 by a χ2 test) than the ratio of the total number of DEGs to the total number of expressed genes (Table 1). Based on categorization by cellular components, DEGs such as those categorized in “membrane” and “cell wall” were significantly overrepresented in the plants infected with RGSV, whereas the influence of RGSV infection on the expression of genes categorized in “ribosome” and “cytosol” appeared to be limited (Table 1). Based on categorization by cellular processes, DEGs involved in stress responses and secondary metabolism were overrepresented in the plants infected with RGSV (Table 1). For DEGs categorized in stress responses, the number of induced genes was significantly greater than that of suppressed genes, whereas the number of induced genes involved in secondary metabolism was not significantly different from that of suppressed genes. On the other hand, expression of genes involved in translation process and nucleic acid metabolism was less influenced by RGSV infection than genes in other categories (Table 1). These results indicated that genes involved in development of cell structures, secondary metabolisms, and stress responses were noticeably affected by RGSV infection, and might be associated with RGSV-induced symptoms.

Cell wall-related genes

The expression of genes related to cell wall components was affected by RGSV infection (Table 2). The expression of genes for cellulose synthase (-like) and arabinogalactan proteins associated with cell wall formation was predominantly suppressed by RGSV infection (Table 2). The genes encoding expansin proteins involved in cell elongation by loosening cell wall components (Choi et al., 2003) were also predominantly suppressed by RGSV infection (Table 2). These results indicate that RGSV infection suppressed both cell wall formation and cell elongation in rice.

Table 2.

Genes related to cell wall components and tillering in RGSV-infected plants that are up- or down-regulated.

| Classification | Locusa | Log2 Ratiob | Responsec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose synthase | LOC_Os0lg54620 | −0.70 | D |

| LOC_Os05g08370 | −0.68 | D | |

| LOC_Os07g2419 | −1.03 | D | |

| LOC_Os10g32980 | −1.09 | D | |

| LOC_Os12g29300 | −0.77 | D | |

| Cellulose synthase-like family A | LOC_Os02g09930 | −2.20 | D |

| LOC_Os02g51060 | −0.60 | D | |

| LOC_Os06g12460 | −1.28 | D | |

| LOC_Os08g33740 | −2.03 | D | |

| Cellulose synthase-like family C | LOC_Os01g56130 | −0.68 | D |

| LOC_Os03g56060 | 1.10 | U | |

| LOC_Os08g15420 | −0.84 | D | |

| Cellulose synthase-like family E | LOC_Os09g30120 | 1.13 | U |

| LOC_Os09g30130 | −1.21 | D | |

| Cellulose synthase-like family F | LOC_Os07g36610 | −0.89 | D |

| LOC_Os07g36690 | −2.80 | D | |

| LOC_Os07g36700 | −1.99 | D | |

| LOC_Os07g36740 | −1.34 | D | |

| LOC_Os08g06380 | −0.92 | D | |

| Cellulose synthase-like family H | LOC_Os04g35030 | 1.35 | U |

| Fasci din-like arabinogalactan protein | LOC_Os03g57460 | −1.07 | D |

| LOC_Os07g06680 | −0.73 | D | |

| LOC_Os08g38270 | −1.03 | D | |

| LOC_Os05g07060 | −1.76 | D | |

| LOC_Os05g48900 | −0.73 | D | |

| LOC_Os08g39270 | 1.38 | U | |

| LOC_Os05g38500 | −0.99 | D | |

| LOC_Os03g03600 | −1.38 | D | |

| LOC_Os08g23180 | −1.02 | D | |

| LOC_Os09g07350 | −1.39 | D | |

| LOC_Os09g30010 | 1.78 | U | |

| α-Expansin | LOC_Os01g14660 | −2.34 | D |

| LOC_Os02g51040 | −1.28 | D | |

| LOC_Os03g60720 | 2.28 | U | |

| LOC_Os04g15840 | −1.12 | D | |

| LOC_Os05g39990 | −0.77 | D | |

| LOC_Os06g41700 | 0.90 | U | |

| LOC_Os10g30340 | −1.24 | D | |

| β-Expansin | LOC_Os03g01270 | −2.06 | D |

| LOC_Os 10g40710 | −2.26 | D | |

| Expansin-like | LOC_Os03g04020 | −0.90 | D |

| LOC_Os06g50960 | −0.66 | D | |

| LOC_Os10g39640 | −1.36 | D | |

| Extensin | LOC_Os01g67390 | −2.86 | D |

| LOC_Os04g32850 | −1.66 | D | |

| LOC_Os11g41120 | 1.73 | U | |

| OsNACs/Ostiin | LOC_Os04g38720 | 0.58 | U |

| RCN1 | LOC_Os03g17350 | 2. 47 | U |

| SPL14 | LOC_Os03g39890 | −0.65 | D |

Based on Rice Genome Annotation Project database Osa1 (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu).

Log2-based differential expression ratio (signal intensity in RTSV-infected plant/signal intensity in mock-inoculated plant).

U (D): Significantly induced (suppressed) by RGSV infection.

Genes associated with tillering

One of the major symptoms caused by RGSV infection is excessive tillering. The genes RCN1 (REDUCED CULM NUMBER 1; Yasuno et al., 2009), SPL14 (SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE 14; Miura et al., 2010), and Ostill1 (ORYZA SATIVA TILLERING 1; Mao et al., 2007) were reported to promote shoot branching. RGSV infection induced the expression of RCN1and Ostill1, but suppressed that of SPL14 (Table 2), suggesting that activation of RCN1 and Ostill1 alone may contribute to the development of excess tillers in RGSV-infected plants.

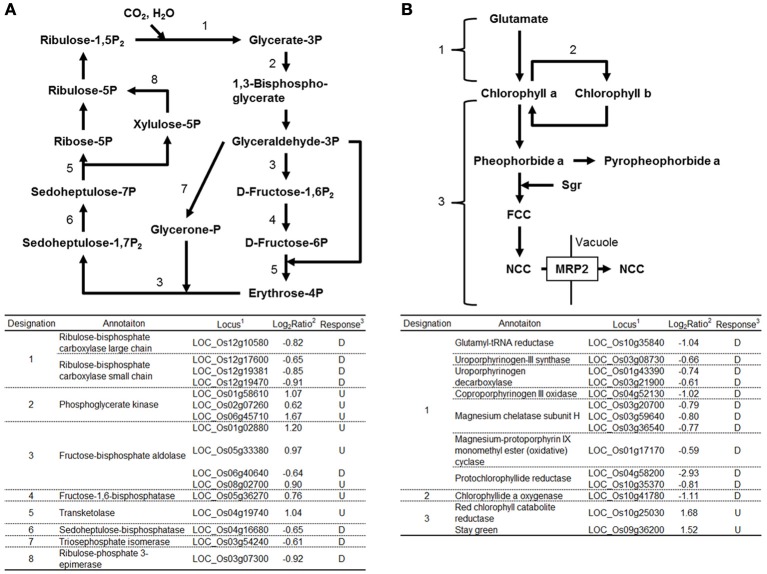

Genes functioning in chloroplast

Expression of many genes functioning in chloroplasts was affected by RGSV infection (Supplementary Material 1). Eight genes functioning in the Calvin-Benson cycle were induced by RGSV infection, whereas 8 genes including those encoding ribulose bisphosfate carboxylase (Rubisco) large and small subunits were suppressed (Figure 2A). Among 35 genes involved in the photosynthesis system whose expression was affected by RGSV, 34 were suppressed in RGSV-infected plants (Supplementary Material 1). The chlorophyll is a photoreceptor in the chloroplast. Among 14 genes for chlorophyll metabolism whose expression was affected by RGSV infection, 12 genes were suppressed and 2 genes were induced (Figure 2B). The suppressed genes were those involved in chlorophyll synthesis and conversion. The two induced genes were Staygreen (Sgr) and the gene encoding red chlorophyll catabolite reductase, both of which are associated with chlorophyll degradation (Park et al., 2007). Thus, it is likely that RGSV infection inhibits the carbon fixation and chlorophyll synthesis, and promotes degradation of chlorophyll.

Figure 2.

Genes related to Calvin-Benson cycle and chlorophyll metabolisms in RGSV-infected plants that are up- or down-regulated. Responses of genes for (A) Calvin-Benson cycle, and (B) chlorophyll metabolism. Enzymes catalyzing reactions are shown in the table below: 1based on Rice Genome Annotation Project database Osa1 (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu), 2log2-based differential expression ratio (signal intensity in RTSV-infected plant/signal intensity in mock-inoculated plant), and 3U (D): Significantly induced (suppressed) by RGSV infection.

Expression of genes associated with plant hormone metabolism and signaling

We examined the expression patterns of genes involved in plant hormone biosynthesis and signaling processes. Rice genes for hormone biosynthesis and signaling and their orthologous genes in Arabidopsis are described in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (Kanehisa et al., 2010).

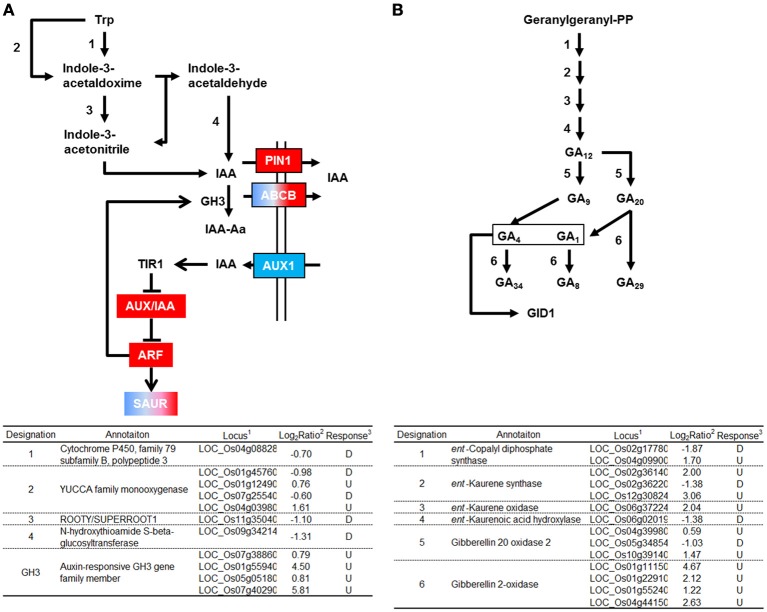

Genes related to auxin biosynthesis and signaling

GH3 converts IAA into an inactive form by conjugating IAA to amino acids (Domingo et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Four genes encoding GH3 were activated by RGSV infection (Figure 3A). RGSV infection also affected the expression of genes for auxin transporters such as AUX1/LAX1, PIN1, and ABCB (Figure 3A, Supplementary Material 1). RGSV suppressed AUX1/LAX1 genes, but activated OsPIN1 genes. RGSV infection induced the genes for the regulator of auxin signaling such as AUX/IAA and ARF (AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR) (Lau et al., 2008) (Figure 3A). The expression of SAUR (SMALL AUXIN-UP RNA) genes involved in regulation of auxin synthesis and transport (Kant et al., 2009) was also affected by RGSV infection, and the number of induced SAUR genes was similar to that of suppressed genes (Figure 3A). These results suggest that RGSV infection might have inhibited the accumulation of auxin in rice, but activates IAA signaling process.

Figure 3.

Genes related to auxin and gibberellic acid biosynthesis and signaling in RGSV-infected plants that are up- or down-regulated. Responses of genes for (A) auxin metabolisms and signaling, and (B) gibberellic acid (GA) metabolism. Enzymes catalyzing reactions are shown in the table below: 1based on Rice Genome Annotation Project database Osa1 (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu), 2log2-based differential expression ratio (signal intensity in RTSV-infected plant/signal intensity in mock-inoculated plant), and 3U (D): Significantly induced (suppressed) by RGSV infection. Boxes of red (or blue) indicate that the corresponding genes are predominantly induced (or suppressed). Boxes of red/blue indicate that the number of the corresponding genes induced was similar to that of suppressed genes. →: Reaction and translocation of substrate →: Positive signaling ⊣: Negative signaling.

Genes related to gibberellic acid (GA) biosynthesis and signaling

Enzymes such as ent-kaurene synthase (KS), ent-kaurene oxidase (KO), and gibberellin 20-oxidase (GA20ox) catabolize the production of bioactive GA precursor (Yang and Hwa, 2008, and references therein). Five genes encoding these enzymes were induced by RGSV infection (Figure 3B). RGSV infection also activated the expression of four genes encoding gibberellin 2-oxidase (GA2ox), which degrades bioactive GA. The expression of genes for GA metabolism is regulated by Dwarf 62 (D62) and YABBY1 transcription factors (Dai et al., 2007; Li et al., 2010). The genes encoding D62 and YABBY1 were induced and suppressed by RGSV infection, respectively (Supplementary Material 1). On the other hand, the expression of genes encoding GID1, DELLA, and GID2, which are involved in GA signaling (Itoh et al., 2008), was not affected by RGSV infection (Supplementary Material 1). These results suggest that RGSV infection might have induced both GA biosynthesis and GA degradation.

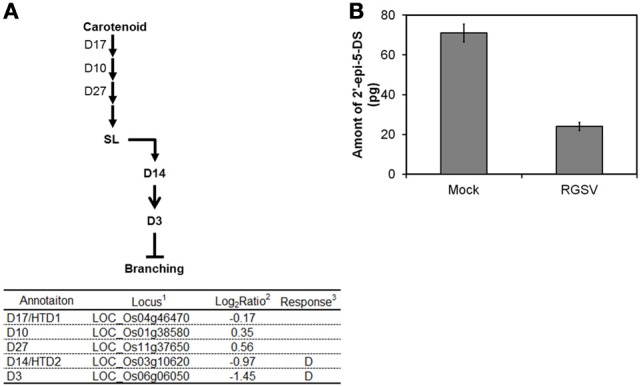

Gene related to strigolactone (SL) biosynthesis and signaling

SL was recently classified as a plant hormone. The expression of genes involved in SL biosynthesis such as those encoding Dwarf 17 (D17), D10, and D27 was not changed by RGSV infection (Figure 4A). We quantified 2′-epi-5-deoxystrigol, one of the major SLs n rice, in root exudates to examine whether endogenous SL level was changed by RGSV infection. Quantification of 2′-epi-5-deoxystrigol was made on plant tissue at 42 dpi instead of 28 dpi, because the symptoms induced by RGSV infection were clearly observed at this stage. The amounts of 2′-epi-5-deoxystrigol were low in both RGSV and mock plants (Figure 4B), but it seemed that RGSV infection suppressed the strigolactone synthesis. HTD2 (HIGH TILLERING DWARF 2) and D3 are related to SL signaling (Umehara et al., 2010; Yamaguchi and Kyozuka, 2010). The expression of the two genes was suppressed by RGSV infection. These results suggest that SL synthesis and signaling in rice might have been suppressed by RGSV infection.

Figure 4.

Influence of RGSV infection on strigolactone biosynthesis and signaling. Responses of genes for (A) strigolactone metabolisms and signaling. Enzymes catalyzing reactions are shown in the table below: 1Based on Rice Genome Annotation Project database Osa1 (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu), 2Log2-based differential expression ratio (signal intensity in RTSV-infected plant/signal intensity in mock-inoculated plant), 3D: Significantly suppressed by RGSV infection. (B) Strigolactone in root exudates from mock-inoculated and RGSV-infected plants. →: Reaction and translocation of substrate → : Positive signaling ⊣: Negative signaling.

Discussion

We previously reported gene responses of rice to RSV and Rice dwarf virus (RDV) (Shimizu et al., 2007; Satoh et al., 2010, 2011). RSV is the type member of Tenuivirus and RDV belongs to the genus Phytoreovirus. Symptoms such as leaf stripe and stunting are common to plants infected with either virus. Symptoms caused by RSV infection are shown in Supplementary Material 3. The transcriptome analyses of plants infected with either virus commonly showed the predominant suppression of genes involved in cell wall synthesis, GA synthesis and chloroplast function, implying strong associations of such gene responses with leaf stripes and stunting. We expected that the symptoms of leaf yellowing, stunting and excessive tillering caused by RGSV are also associated with specific gene responses in RGSV-infected plants. In this study, we focused on the responses of genes involved in cell wall formation, chloroplast function, and hormone biosynthesis and signal transduction since expression of these groups of genes were also significantly affected in rice plants infected with RDV and RSV (Shimizu et al., 2007; Satoh et al., 2010, 2011).

Gene expression responses associated with stunting and leaf yellowing in RGSV infected plants

RGSV infection induces stunting of rice plants. Many cellulose synthase (-like) genes were suppressed in RGSV-infected plants (Table 2). The suppression of many cellulose synthase (-like) genes was also seen in RSV-infected plants, which exhibits stunting symptom (Satoh et al., 2010). Expansins mediate loosening of cell wall. Suppression of OsEXP4, one of the rice expansin genes, resulted in stunted growth (Choi et al., 2003). The expression of many expansin (-like) genes were suppressed by RGSV infection. The suppression of many expansin genes was also observed in RSV-infected plants (Satoh et al., 2010). Therefore, the suppression of cellulose synthase and expansin genes is one of the common gene responses associated with stunting of rice infected with tenuiviruses.

The expression of the Rubisco genes was suppressed by RGSV infection (Figure 2A). The suppression of the Rubisco genes was also observed in RSV-infected plants (Satoh et al., 2010). RGSV-infected plants show leaf yellowing (Figure 1), implying the chlorophyll contents may have been decreased by RGSV infection. The appearance of leaf chlorosis in RSV-infected plants is different from that in RGSV-infected plants. RSV-infected plant showed white stripes on leaves (Satoh et al., 2010). The difference in leaf chlorosis pattern may have resulted from the difference in influence by RGSV and RSV on chlorophyll synthesis and degradation processes. In RGSV-infected plants, the expression of genes involved in chlorophyll synthesis was suppressed, and the suppression of those genes was also detected in RSV-infected plants. This suppression indicates that RGSV-infected plants contain low chlorophyll content, and have lower photosynthesis activity than healthy plants. These suggest that decreased biomass accumulation such as cell wall synthesis and carbon fixation activity may account for stunting of the virus-infected plants.

The difference in leaf chlorosis pattern may be related to chlorophyll degradation process (Figure 2B). The degradation of chlorophyll is regulated by Sgr gene (Park et al., 2007). Overexpression of Sgr resulted in yellowing leaves which is similar to the disease symptoms of RGSV-infected plants (Park et al., 2007). The expression of Sgr gene was induced by RGSV infection (Figure 2). Thus, the activation of Sgr by RGSV infection may play a role to induce the leaf yellowing symptom. In RSV-infected plants, the expression of genes involved in chlorophyll degradation was also activated, but the expression of Sgr was not significantly changed (Satoh et al., 2010). Therefore, the difference in the appearance of leaf chlorosis between the plant infected with RGSV and that infected with RSV may be related to the activation of Sgr.

Cell elongation is controlled by plant hormones such as GA and IAA. The expression of genes for GA biosynthesis such as those for KS, KO, and GA20ox, and those involved in GA inactivation such as the genes for GA2ox increased in RGSV-infected plants (Figure 3B), whereas the expression of these genes decreased in plants infected with RSV (Satoh et al., 2010). It was reported that rice plants overexpressing GA2ox contained lower bioactive GA, and were shorter than the wild type (Lo et al., 2008). The expression of GA2ox increased in stunted rice plants after infection with RDV (Satoh et al., 2011). These observations, in total, suggest that there are multiple ways to reduce the bioactive GA content and produce stunted plants, and that for RGSV an induction of GA2ox may aid in producing the stunted plants. On the other hand, many genes for both GA biosynthesis and degradation were suppressed in plants infected with RSV, which may have caused a reduction in GA content. Sakamoto et al. (2004) reported that a GA-deficient mutant was stunted. Therefore, the stunting symptom of RSV-infected plants might be related to GA deficiency. These observations indicate that RGSV- and RSV-infected plants may contain low bioactive GA, though the pathways to the reduction may be different between the plant infected with RGSV and that infected with RSV.

RGSV infection suppressed the genes for IAA biosynthesis, and induced the genes for IAA inactivation (Figure 3A). This implies that IAA content decreases in plants infected with RGSV. In addition, RGSV infection increased the expression of GH3 genes (Figure 3A). It is known that the activation of GH3 genes inhibits plant growth by suppressing genes related to auxin biosynthesis and signaling, and those for expansin (Ding et al., 2008; Domingo et al., 2009). The activation of GH3 genes was also observed in RSV-infected plants (Satoh et al., 2010). These observations suggest that stunting of plants infected with rice tenuiviruses is associated with a reduction in auxin content.

Overexpression of a SAUR gene resulted in various morphological changes in rice plants (Kant et al., 2009). The expression of a SAUR gene was conspicuously induced in Arabidopsis thaliana by Beet curly top virus (BCTV), and the induction of the SAUR gene was correlated with symptom development and tissue-specific accumulation of BCTV (Park et al., 2004). The expression of many SAUR genes was found to be regulated in the plants infected with RGSV (Supplementary Material 1, Figure 3A), RDV (Satoh et al., 2011), and RSV (Satoh et al., 2010). Among the regulated SAUR genes, OsSAUR13, OsSAUR26, and OsSAUR33 were commonly activated by RGSV and RDV, whereas OsSAUR8, OsSAUR30, OsSAUR44, OsSAUR46, OsSAUR53, OsSAUR57, and OsSAUR58 were commonly suppressed by RGSV, RDV and RSV. Consequences of the regulated expression of various SAUR genes in the RGSV-infected plant are not clear, but the SAUR genes commonly regulated by RGSV, RDV, and RSV may be associated with stunted growth of plants infected with these viruses.

Gene associated with excess tillering by RGSV infection

Excess tillering (shoot branching) is RGSV-specific symptoms. Shoot branching is controlled by plant hormones (Dill and Sun, 2001; Ferguson and Beveridge, 2009; Shimizu-Sato et al., 2009). Auxin and SL inhibit shoot branching, whereas cytokinin promotes it. In RGSV-infected plants, genes related to IAA biosynthesis were suppressed and those related to IAA degradation were induced (Figure 3A), implying that the IAA content was decreased by RGSV infection. The suppression of genes involved in IAA synthesis genes and the induction of genes involved in IAA degradation genes were also observed in RSV-infected plants which do not show excess tillers. These indicate that the reduction in auxin content is not directly associated with the excess tillering of RGSV-infected plants. A rice plant overexpressing the GH3-8 displayed phenotypes of dwarfism and excess tillering (Ding et al., 2008) which are similar to the symptoms of RGSV-infected plants. However, the activation of GH3-8 was also observed in RSV-infected plants. Therefore, the induction of the GH3 genes in RGSV-infected plants may not be related to excess tillering.

Rice genes D10, D17/HTD1, and D27 are involved in SL biosynthesis, and D3 and D14/HTD2 are involved in SL signaling (Arite et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009; Yamaguchi and Kyozuka, 2010). Rice mutants for these genes have more tillers than the wild type. The expression of D3 and D14/HTD2 was suppressed in rice plants infected with RGSV (Figure 4), implying that the SL signaling process is repressed by RGSV infection. In addition, endogenous SL was reduced by RGSV infection (Figure 4). The expression of D17/HTD1 was also suppressed in RSV-infected plants. Thus, SL biosynthesis might have been suppressed by RSV infection. These results suggest that excessive tillering because of RGSV infection may be related to the repression of SL signaling, but not to the decrease in SL content in RGSV-infected plants.

A reduction in active GA also promotes the formation of axillary buds (Curtis et al., 2005; Lo et al., 2008). GA2ox is one of the key genes for GA degradation to produce inactive GA (Curtis et al., 2005; Lo et al., 2008). Overexpression of GA2ox in rice resulted in development of excess tillers, a decrease in bioactive GA, and an increase in inactive GA (Lo et al., 2008). RGSV infection induced GA2ox (Figure 3B). Thus, it is likely that RGSV infection decreases bioactive GA content and increase inactive GA content in rice plants. On the other hand, genes involved in biosynthesis and degradation of bioactive GA were suppressed by RSV infection (Satoh et al., 2010), indicating that GA content may have been decreased by RSV infection. Plants deficient in GA display stunted growth and reduced tillers (Margis-Pinheiro et al., 2005), which are similar to the symptoms caused by RSV. These observations suggest that excessive tillering because of RGSV infection is related to the accumulation of inactive GA, but not to the lack of bioactive GA.

Overall, excessive tillers induced specifically by RGSV infection might be a consequence from the additive actions of SL, GA, and the genes regulating shoot branching, such as RCN1and Ostill1. Examination for possible interactions between RGSV proteins and host proteins, and phenotypes of transgenic plants with RGSV genes may help to elucidate the molecular mechanism of excessive tillering caused by RGSV infection. Moreover, there could be modifications in gene expression that occur earlier than 28 dpi, and further studies will determine how such modifications influence the symptoms observed at 28 dpi.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bill Hardy for editing this manuscript and Ms. Setsuko Kimura and Hiromi Satoh for their support in the microarray and semi-quantitative RT-PCR experiments. This work was supported by a grant from the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences (PROBRAIN).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Materials for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00313/abstract

List of expressed genes and differentially expressed genes in RGSV-infected plants.

Examination of expression of selected genes by RT-PCR. The numbers below DNA band images are average log2 (signal intensity of microarray data) for the corresponding genes in mock-inoculated or RGSV-infected plants (Supplementary Material 1).

Symptoms in rice caused by RSV infection. Rice plants at 60 days after RSV inoculation and mock inoculation.

References

- Arite T., Umehara M., Ishikawa S., Hanada A., Maekawa M., Yamaguchi S., et al. (2009). d14, a strigolactone-insensitive mutant of rice, shows an accelerated outgrowth of tillers. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1416–1424 10.1093/pcp/pcp091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D., Lee Y., Cho H. T., Kende H. (2003). Regulation of expansin gene expression affects growth and development in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell 15, 1386–1398 10.1105/tpc.011965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis I. S., Hanada A., Yamaguchi S., Kamiya Y. (2005). Modification of plant architecture through the expression of GA2-oxidase under the control of an estrogen inducible promoter in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Planta 222, 957–967 10.1007/s00425-005-0037-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Zhao Y., Ma Q., Hu Y., Hedden P., Zhang Q., et al. (2007). The rice YABBY1 gene is involved in the feedback regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant Physiol. 144, 121–133 10.1104/pp.107.096586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardick C. (2007). Comparative expression profiling of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves systemically infected with three fruit tree viruses. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 20, 1004–1017 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill A., Sun T. (2001). Synergistic derepression of gibberellin signaling by removing RGA and GAI function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 159, 777–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Cao Y., Huang L., Zhao J., Xu C., Li X., et al. (2008). Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate- and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell 20, 228–240 10.1105/tpc.107.055657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo C., Andrés F., Tharreau D., Iglesias D. J., Talón M. (2009). Constitutive expression of OsGH3.1 reduces auxin content and enhances defense response and resistance to a fungal pathogen in rice. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 22, 201–210 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A. E. (2002). Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 207–210 10.1093/nar/30.1.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson B. J., Beveridge C. A. (2009). Roles for auxin, cytokinin, and strigolactone in regulating shoot branching. Plant Physiol. 149, 1929–1944 10.1104/pp.109.135475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H. (1996). Biology and epidemiology of rice viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34, 249–273 10.1146/annurev.phyto.34.1.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Matsuoka M. (2008). Molecular biology of gibberellins signaling in higher plants. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 268, 191–221 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)00806-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S., Furumichi M., Tanabe M., Hirakawa M. (2010). KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D355–D360 10.1093/nar/gkp896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant S., Bi Y.-M., Zhu T., Rothstein S. (2009). SAUR39, a Small Auxin-Up RNA gene, acts as a negative regulator of auxin synthesis and transport in rice. Plant Physiol. 151, 691–701 10.1104/pp.109.143875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S., Jürgens G., De Smet I. (2008). The evolving complexity of the auxin pathway. Plant Cell 20, 1738–1746 10.1105/tpc.108.060418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Wu J., Weng S., Zhang Y., Zhang D., Shi C. (2010). Identification and characterization of dwarf 62, a loss-of-function mutation in DLT/OsGRAS-32 affecting gibberellin metabolism in rice. Planta 232, 1383–1396 10.1007/s00425-010-1263-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Wang R., Qian Q., Yan M., Meng X., Fu Z., et al. (2009). DWARF27, an iron-containing protein required for the biosynthesis of strigolactones, regulates rice tiller bud outgrowth. Plant Cell 21, 1512–1525 10.1105/tpc.109.065987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo S. F., Yang S. Y., Chen K. T., Hsing Y. I., Zeevaart J. A., Chen L. J., et al. (2008). A novel class of gibberellin 2-oxidases control semidwarfism, tillering, and root development in rice. Plant Cell 20, 2603–2618 10.1105/tpc.108.060913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Du Z. X., Kong J., Chen L. N., Qiu Y. H., Li G. F., et al. (2012). Transcriptome analysis of Nicotiana tabacum infected by Cucumber mosaic virus during systemic symptom development. PLoS ONE 7:e43447 10.1371/journal.pone.0043447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C., Ding W., Wu Y., Yu J., He X., Shou H., et al. (2007). Overexpression of a NAC-domain protein promotes shoot branching in rice. New Phytol. 176, 288–298 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02177.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margis-Pinheiro M., Zhou X. R., Zhu Q. H., Dennis E. S., Upadhyaya N. M. (2005). Isolation and characterization of a Ds-tagged rice (Oryza sativa L.) GA-responsive dwarf mutant defective in an early step of the gibberellin biosynthesis pathway. Plant Cell Rep. 23, 819–833 10.1007/s00299-004-0896-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K., Ikeda M., Matsubara A., Song X. J., Ito M., Asano K., et al. (2010). OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nat. Genet. 42, 545–549 10.1038/ng.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Hwang H., Shim H., Im K., Auh C.-K., Lee S., et al. (2004). Altered cell shapes, hyperplasia, and secondary growth in Arabidopsis caused by beet curly top geminivirus infection. Mol. Cells 17, 117–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Yu J. W., Park J. S., Li J., Yoo S. C., Lee N. Y., et al. (2007). The senescence-induced staygreen protein regulates chlorophyll degradation. Plant Cell 19, 1649–1664 10.1105/tpc.106.044891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce E. J., Rey M. E. (2013). Assessing global transcriptome changes in response to South African cassava mosaic virus [ZA-99] infection in susceptible Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 8:e67534 10.1371/journal.pone.0067534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez B. C. (2008). Tenuivirus, in Encyclopedia of Virology (Third Edition), eds Mahy B. W. J., van Regenmortel M. H. V. (Paris: CNRS; ), 24–27 [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T., Miura K., Itoh H., Tatsumi T., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Ishiyama K., et al. (2004). An overview of gibberellin metabolism enzyme genes and their related mutants in rice. Plant Physiol. 134, 1642–1653 10.1104/pp.103.033696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K., Kondoh H., Sasaya T., Shimizu T., Choi I. R., Omura T., et al. (2010). Selective modification of rice (Oryza sativa) gene expression by rice stripe virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 91, 294–305 10.1099/vir.0.015990-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K., Shimizu T., Kondoh H., Hiraguri A., Sasaya T., Choi I. R., et al. (2011). Relationship between symptoms and gene expression induced by the infection of three strains of Rice dwarf virus. PLoS ONE 6:e18094 10.1371/journal.pone.0018094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikata E., Senboku T., Ishimizu T. (1980). The causal agent of rice grassy stunt disease. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Series B 56, 89–94 10.2183/pjab.56.89 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T., Ogamino T., Hiraguri A., Nakazono-Nagaoka E., Uehara-Ichiki T., Nakajima M., et al. (2013). Strong resistance against Rice grassy stunt virus is induced in transgenic rice plants expressing double-stranded RNA of the viral genes for nucleocapsid or movement proteins as targets for RNA interference. Phytopathology 103, 513–519 10.1094/PHYTO-07-12-0165-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T., Satoh K., Kikuchi S., Omura T. (2007). The repression of cell wall- and plastid-related genes and the induction of defense-related genes in rice plants infected with Rice dwarf virus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 20, 247–254 10.1094/MPMI-20-3-0247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu-Sato S., Tanaka M., Mori H. (2009). Auxin-cytokinin interactions in the control of shoot branching. Plant Mol. Biol. 69, 429–435 10.1007/s11103-008-9416-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umehara M., Hanada A., Magome H., Takeda-Kamiya N., Yamaguchi S. (2010). Contribution of strigolactones to the inhibition of tiller bud outgrowth under phosphate deficiency in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1118–1126 10.1093/pcp/pcq084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S., Kyozuka J. (2010). Branching hormone is busy both underground and overground. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1091–1094 10.1093/pcp/pcq088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. C., Hwa C. M. (2008). Genetic modification of plant architecture and variety improvement in rice. Heredity 101, 396–404 10.1038/hdy.2008.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuno N., Takamure I., Kidou S., Tokuji Y., Ureshi A. N., Funabiki A., et al. (2009). Rice shoot branching requires an ATP-binding cassette subfamily G protein. New Phytol. 182, 91–101 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama K., Xie X., Kim H. I., Kisugi T., Nomura T., Sekimoto H., et al. (2011). How do nitrogen and phosphorus deficiencies affect strigolactone production and exudation? Planta 235, 1197–1207 10.1007/s00425-011-1568-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. W., Li C. H., Cao J., Zhang Y. C., Zhang S. Q., Xia Y. F., et al. (2009). Altered architecture and enhanced drought tolerance in rice via the down-regulation of indole-3-acetic acid by TLD1/OsGH3.13 activation. Plant Physiol. 151, 1889–1901 10.1104/pp.109.146803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of expressed genes and differentially expressed genes in RGSV-infected plants.

Examination of expression of selected genes by RT-PCR. The numbers below DNA band images are average log2 (signal intensity of microarray data) for the corresponding genes in mock-inoculated or RGSV-infected plants (Supplementary Material 1).

Symptoms in rice caused by RSV infection. Rice plants at 60 days after RSV inoculation and mock inoculation.