Abstract

Chronic exposure to diesel exhaust particulates (DEP) increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in urban residents, predisposing them to the development of several cardiovascular stresses, including myocardial infarctions, arrhythmias, thrombosis, and heart failure. DEP contain a high level of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). We hypothesize that exposure to DEP elicits ventricular remodeling through the activation of the AHR pathway, leading to ventricular dilation and dysfunction. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed by nose-only nebulization to DEP (SRM 2975, 0.2 mg/ml) or vehicle for 20 min/day × 5 wk. DEP exposure resulted in eccentric left ventricular dilation (8% increased left ventricular internal diameter at diastole and 23% decreased left ventricular posterior wall thickness at diastole vs. vehicle), as shown by echocardiograph assessment. Histological analysis using Picrosirius red staining revealed that DEP reduced cardiac interstitial collagen (23% decrease vs. vehicle). Further assessment of cardiac function using a pressure-volume catheter indicated impaired diastolic function (85% increased end-diastolic pressure and 19% decreased Tau vs. vehicle) and contractility (57 and 48% decreased end-systolic pressure-volume relationship and maximum change in pressure over time vs. end-diastolic volume compared with vehicle, respectively) in the DEP-exposed animals. Exposure to DEP significantly increased cardiac expression of AHR (19% increase vs. vehicle). In addition, DEP significantly decreased the cardiac expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α, the competitive pathway to the AHR, and vascular endothelial growth factor, a downstream mediator of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (26 and 47% decrease vs. vehicle, respectively). These findings indicate that exposure to DEP induced left ventricular dilation by loss of collagen through an AHR-dependent mechanism.

Keywords: diesel exhaust particulates, cardiac dysfunction, cardiac remodeling, collagen

in the united states, approximately 60,000 deaths annually are attributed to particulate air pollution (41). Acute and chronic exposure to particulate matter (PM) is linked to several cardiac diseases, including myocardial infarctions, arrhythmias, thrombosis, and heart failure; however, the mechanisms whereby particles produce cardiac toxicity are largely unknown (5). Several researchers have demonstrated that exposure to PM can produce cardiac dysfunction, but the changes observed differ according to the type of particle, route of exposure, and duration of exposure, leaving much controversy as to how exposure to particulates impacts the heart (12, 28, 35, 42). Moreover, it is not known how exposure to PM impacts the heart's structural extracellular matrix (ECM), which is a critical component of cardiac function.

The myocardial ECM plays a pivotal role in maintaining the structure of the heart. The ECM is complex and composed of a fibrillar collagen network, basement membrane proteins, proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and bioactive signaling molecules (27). Cardiac structure is primarily regulated through the accumulation and degradation of collagen (6, 27). Under normal physiological conditions, collagen turnover is tightly regulated; however, pathological conditions can disrupt this balance (10, 21, 34). In the chronic pressure overloaded heart, e.g., during hypertension, there is an increased deposition of extracellular collagen, causing stiffness of the ventricular wall (2, 22). Conversely, in the case of chronic volume overload, a condition observed with valve regurgitation, collagen turnover is shifted toward degradation, resulting in a loss of extracellular collagen, causing dilation of the chamber and weakening of the ventricular wall (10, 17, 22, 40). In either case, dysregulation of this balance, either toward accumulation or degradation, results in a change of cardiac structure and function.

Diesel exhaust particulates (DEP) are the most abundant outdoor source of airborne PM (9). DEP is composed of a heterogenous mixture of carbon, inorganic compounds, and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), ranging from fine (2.5–0.1 μm diameter) to ultrafine (<0.1 μm diameter) particles (9). The PAHs found in DEP are known ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) (14, 19, 30, 31). AHR signaling plays an important role in ECM remodeling (1, 25, 29, 38). AHR activation promotes collagen loss in various tissues, including human periodontal ligaments and Zebra fish fins (1, 38).

The role of the AHR is to mitigate the toxic effects induced by halogenated aryl hydrocarbons (31). Due to their hydrophilic nature, hydrocarbons diffuse across the cell membrane to initiate the AHR signaling cascade (14, 19, 30, 31). Binding of the hydrocarbon ligand stimulates the dissociation of AHR-associated proteins, activating the receptor and inducing translocation into the nucleus, allowing for dimerization with the AHR nuclear transporter (ARNT) (14, 19, 30, 31). The AHR/ARNT heterodimer binds to the xenobiotic response element in the promoter region of genes involved in the expression of various biological and toxicological responses, including cytochrome P-450 (Cyp) enzymes, specifically Cyp 1A1 (14, 19, 30, 31).

The ARNT can also bind with hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α to regulate gene expression during low oxygen stress (31). Under aerobic conditions, HIF-1α is continuously synthesized and degraded. During hypoxia, HIF-1α degradation is inhibited, and translocation to the nucleus is triggered. Upon translocation, HIF-1α competitively dimerizes with ARNT and binds the hypoxic response element in the promoter region, inducing the transcription of various genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (19, 31).

Both the AHR and HIF-1α signaling pathways can alter ventricular structure. Thackaberry and colleagues (36) demonstrated that AHR−/− null mice, with increased cardiac expression of HIF-1α and VEGF, exhibited left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, a phenotype consistent with pressure overload. Conversely, in the AHR+/+ mice, the overexpression of AHR led to a volume overload phenotype with LV dilation (36). Although controversy remains regarding the regulation of these two pathways, activation of either the AHR or HIF-1α may be dependent on the concentration of the AHR's ligand. Chronic exposure to the aryl hydrocarbons found in DEP leads to prolonged activation of the AHR, causing attenuation of the HIF-1α pathway (31). We hypothesize that, through the activation of the AHR, exposure to DEP induces ECM remodeling by shifting the collagenous ECM balance toward degradation, leading to loss of collagen, and ultimately causing ventricular dilation and dysfunction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Studies were performed using 9-wk-old male Sprague-Dawley (Harlan Hsd:SD) rats. Rats were housed under standard environmental conditions and maintained on rat chow and tap water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were performed according to the principles outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and approved by Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

DEP exposure protocol.

After arrival and a brief (1 wk) acclimation to rodent restrainers, rats were randomly divided into two groups: vehicle (0.9% saline + 0.02% Tween 80; n = 7) and DEP (SRM 2975, 0.2 mg/ml in 0.9% saline + 0.02% Tween 80; n = 8). SRM 2975 is a standard DEP derived from forklift exhaust. The National Institute of Standards and Technologies extensively characterized this particulate for content of PAHs and particle size distribution. This particulate is readily available from the National Institute of Standards and Technologies and can be acquired by other investigators for future comparative studies. The concentration used was based on literature dosing of intratracheal instillation (26). To avoid particle aggregation, all samples were prepared fresh before exposure, vortexed for 20 s, and sonicated for 15 min. Rats were exposed for a total of 20 min/day to either DEP or vehicle for a 5-wk period. The total volume nebulized was 10 ml of either DEP or vehicle. Particles were aerosolized using a PARI nebulizer (PARI Respiratory Equipment) at a flow rate of 8 l/min.

Taking into account the flow rate through our exposure system and the mass of the particles before nebulization, the maximum concentration of exposure was 8.75 mg/m3. This exposure concentration is well above ambient air levels, but represents a physiological high level of exposure. Furthermore, this concentration is comparable to other inhalation studies (23, 24). Previous studies have shown that a 20-min daily exposure to particulates is sufficient to cause LV dysfunction (28). The amount of particulate distributed to the animal during a 20 min exposure is ∼3% of the particle concentration in the nebulized solution, or ∼0.26 mg/m3, which falls within the hazardous range by air quality index (28). The study duration was based on a cigarette smoke exposure study by our laboratory, which found significant changes in cardiac function by 5 wk (4).

Echocardiographic analysis.

Cardiac ventricular dimensions and function were assessed in sedated rats by echocardiography (isoflurane 1.5%; VEVO 770; Visualsonics) 1 day before the start of the exposure protocol, and every week thereafter during the 5-wk protocol. The LV short-axis view was used to obtain B-mode two-dimensional images and M-mode tracings of the ventral (anterior) and dorsal (posterior) LV wall using a two-dimensional reference sector. Echocardiography provided measurements of LV internal diameter (LVID) and posterior wall thickness (LVPW) at diastole (d) and systole (s). LV systolic function was measured by fractional shortening (LVIDd − LVIDs/LVIDd). Eccentric index was evaluated by the relative wall thickness ratio 2 × LVPWd/LVIDd. All measurements were performed on three different cardiac cycles and averaged for each time point.

Pressure-volume loop analysis.

At the end of the fifth week, LV function was assessed using pressure-volume loop analysis. Each rat was weighed, anesthetized with 3.5% isoflurane, and ventilated. The left jugular vein was cannulated. A Scisense pressure-volume catheter (FTS-1912B-9018) was introduced into the right carotid artery and advanced into the LV. Following a 10-min equilibration period; pressure and volume signals were continuously recorded at a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz using the Advantage PV System (model FY897B Scisense, Ontario, CA). Data were acquired using an iWorx 308T data acquisition system with Labscribe software (iWorx) to calculate hemodynamic parameters of heart rate, LV end-systolic pressure, end-diastolic pressure (EDP), end-systolic volume, end-diastolic volume (EDV), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), ejection fraction, and inverse measure of relaxation rate (τ). Load-independent parameters of systolic function [end systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR)], diastolic function [end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (EDPVR)], prerecruitable stroke work, and maximum change in pressure over time (dP/dtmax) vs. EDV were obtained following partial occlusion of the abdominal vena cava to vary preload. All measures of cardiac function were evaluated from a minimum of 10 consecutive pressure-volume loops. For volume calibration, 0.1 m of 15% saline was introduced into the jugular vein of the anesthetized animal, as previously described by Pacher and colleagues (32). After functional assessment, the heart was quickly removed and rinsed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the LV, including septum, and right ventricle were separated and weighed. A portion of the mid-LV region was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the remainder snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Analysis of the collagen matrix.

Interstitial collagen volume fraction (CVF) was calculated from mid-LV sections at the 5-wk end point, as previously described (4, 11, 40). Briefly, LV sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Two sections (5 μm) were cut from each heart, attached to slides, and stained with collagen-specific Picrosirius red. Fluorescent images were captured (×20) using a Nikon Eclipse model no. TE2000-U fluorescence microscope and processed with NIS Elements software. The CVF for each section was determined by analyzing 10 random interstitial samples, taking care to exclude perivascular collagen (20 total samples/heart). The mean CVF for each heart was expressed as percent total area and then group averaged.

Western blot analysis.

Cardiac protein expression was determined using Western blot analysis, as previously described (4). Briefly, LV tissue was homogenized with lysis buffer (RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor). Protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad), and an equal amount of protein (40 μg) was loaded into each lane. Proteins were separated using electrophoresis and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline and 0.01% Tween for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated with the desired primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies used were as follows: AHR NB100-2289, Novus; HIF-1α sc-10790 and GAPDH sc47724, Santa Cruz; transforming growth factor-β 3711, Cell Signaling; matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 ab19015 and MMP-9 AB19016, Millipore; and MMP-8 AB81286 and MMP-13 AB39012, Abcam. Following incubation with secondary antibody, membranes were washed, and enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) used to visualize immunostaining. Data were collected and processed using a Carestream Molecular Imaging Scanner (Gel Logic 2200 Pro). Densitometry data were analyzed, normalized to corresponding GAPDH, and expressed as percent vehicle controls.

Immunohistochemistry.

LV sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Two sections (5 μm) were cut from each heart, attached to slides, and rehydrated through 100 and 95% ethanol and deionized water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the slides in 3% hydrogen peroxide, followed by a rinse in PBS. Sections were blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin for 30 min and incubated over night with 1:4,000 diluted polyclonal rabbit anti-rat CYP 1A1 antibody (Millipore AB1247). After 3 × 5 min washes with PBS, the slides were incubated for 1 h with a 1:1,000 horseradish peroxidase-Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen 65-6120), diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS. After another 3 × 5 min PBS wash, the slides were incubated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma D3939) for 5 min. All slides were washed vigorously with ddH2O counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through 70–100% ethanol and xylene, and mounted in toluene-based media for viewing. Images were taking using a Nikon Eclipse microscope with Nikon Elements analysis software.

Growth factors and cytokines.

Cardiac growth factors and cytokines were measured in LV homogenates using the Milliplex Map Kit Rat Cardiovascular Disease Panel 1 following the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore). LV tissue was homogenized with lysis buffer. The Luminex system utilizes the Luminex xMAP technology based on fluorescent-coded beads conjugated with specific monoclonal antibodies. A Bio-Plex array reader and Bio-Plex Manager software were used to analyze the samples. Tissue interleukin (IL)-1β levels were measured using a commercially available ELISA immunoassay kit (R&D Systems). LV tissue was homogenized (10 mg tissue to 0.1 ml RIPA). Protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad) for normalization of growth factors and cytokines to milligram of total protein.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using analysis software (Graphpad 5.0; Prism). Echocardiographic grouped data comparisons were made using two-way ANOVA. When significant F ratio (P < 0.05) was obtained, between-groups comparisons were made using Bonferroni posttest to compare means. The pressure-volume measurements, CVF, Western blot analysis, and Luminex were analyzed by t-test. Statistical significance was taken to be P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Necropsy evaluation of heart, lung, and body weights.

There were no significant differences in body weight or in LV, right ventricle, or lung-to-body weight ratios for the animals exposed to DEP at the 5-wk end point, compared with vehicle-treated rats (Table 1).

Table 1.

Necropsy evaluation

| Vehicle | DEP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 8 | |

| LV/BW, mg/kg | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 0.13 |

| RV/BW, mg/kg | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.24 |

| Lung/BW, mg/kg | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 0.20 |

| BW, kg | 0.3 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.15 |

Values are means ± SD; n, no. of animals. DEP, diesel exhaust particulates; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; BW, body weight.

Exposure to DEP produces ventricular eccentric dilation.

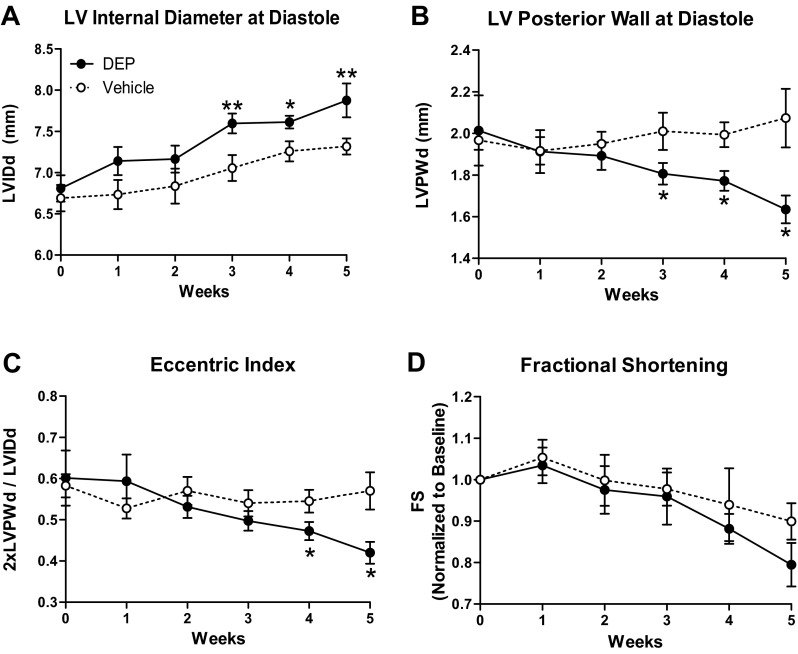

Echocardiographic assessment of LV structure demonstrated that rats exposed to DEP developed a progressive increase in LVIDd with significant dilation evident as early as 3 wk of exposure and continuing to the 5-wk end point (8% increase; Fig. 1A). These rats also exhibited a decrease in LVPWd with significant wall thinning occurring by 3 wk and continuing to 5 wk (23% decrease; Fig. 1B). The eccentric index was significantly reduced in rats exposed to DEP by 4 wk (33% decrease; Fig. 1C). There was no change in fractional shortening (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Diesel exhaust particulates (DEP) induced eccentric left ventricular (LV) dilation. Temporal echocardiogram data demonstrate that exposure to DEP induced LV dilation [LV internal diameter at diastole (LVIDd); A] and LV posterior wall thinning [posterior wall thickness at diastole (LVPWd); B] and reduced eccentric index (2 × LVPWd/LVIDd; C). There was no significant change in fractional shortening (FS) between groups. Values are means ± SE; n = 8 DEP and 7 vehicle. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle. **P < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

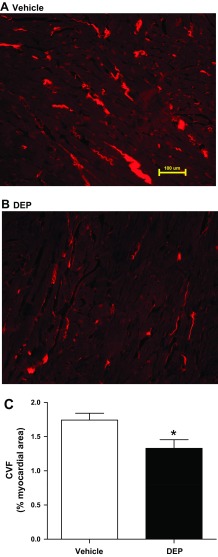

Exposure to DEP reduces interstitial LV collagen.

The interstitial CVF was calculated from Picrosirius red stained midventricular sections. DEP caused a significant decrease in interstitial CVF (23% decrease; Fig. 2). CVF content in vehicle-treated rats was consistent with previous findings from our laboratory (4, 11, 40).

Fig. 2.

DEP reduced myocardial interstitial collagen. Representative collagen staining of LV sections by Picrosirius red (PSR) at the 5-wk end point is shown for vehicle (A) and DEP exposure (B). C: group averaged collagen volume fraction (CVF) calculated from PSR stained mid-LV sections. Values are means ± SE; n = 8 DEP and 7 vehicle. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

Exposure to DEP produces cardiac dysfunction.

LV function was assessed using a steady-state pressure-volume catheter. Table 2 summarizes the pressure-volume data for all animals at the 5-wk end point. Compared with vehicle, DEP exposure resulted in significantly increased EDP (85% increase); however, there were no significant differences in EDV or end-systolic volume between the groups. Exposure to DEP significantly decreased τ (19% decrease). SV, CO, and end-systolic pressure were not significantly different between vehicle and DEP-exposed rats. Heart rate was significantly increased in the DEP rats compared with vehicle (8% increase). Load-independent parameters of contractility, ESPVR, and dP/dtmax vs. EDV were significantly decreased in response to DEP exposure (57 and 48% decrease, respectively; Table 2). There were no significant differences in EDPVR (P = 0.09) or prerecruitable stroke work (P = 0.08) between the groups.

Table 2.

Cardiac functional parameters using pressure-volume catheter

| Vehicle | DEP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 8 | |

| HR, beats/min | 350 ± 8 | 381 ± 10* | <0.05 |

| CO, ml/min | 40 ± 6 | 52 ± 8 | 0.092 |

| ESP, mmHg | 108 ± 6 | 121 ± 10 | 0.15 |

| EDP, mmHg | 8 ± 1 | 13 ± 2* | 0.031 |

| ESV, μl | 278 ± 54 | 307 ± 48 | 0.35 |

| EDV, μl | 387 ± 61 | 452 ± 59 | 0.23 |

| SV, μl/beat | 108 ± 17 | 145 ± 18 | 0.081 |

| EF, % | 30 ± 4 | 34 ± 4 | 0.28 |

| τ, ms | 16 ± 1 | 14 ± 1* | <0.05 |

| ESPVR | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.2* | <0.05 |

| EDPVR | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.096 |

| PRSW, mmHg | 58 ± 6 | 41 ± 10 | 0.085 |

| dP/dt vs. EDV, mmHg·s−1·μl−1 | 22 ± 4 | 11 ± 4* | <0.05 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of animals. Animals were exposed to either vehicle or DEP for 20 min/day for 5 wk. Parameters of LV function were measured 90 min after final exposure. HR, heart rate; CO, cardiac output; ESP, end-systolic pressure; EDP, end-diastolic pressure; ESV, end-systolic volume; EDV, end-diastolic volume; SV, stroke volume; EF, ejection fraction; τ, inverse measure of relaxation rate; ESPVR, end-systolic pressure-volume relationship; EDPVR, end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship; PRSW, preload recruited stroke work; dP/dt, change in pressure over time.

Statistical significance: P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

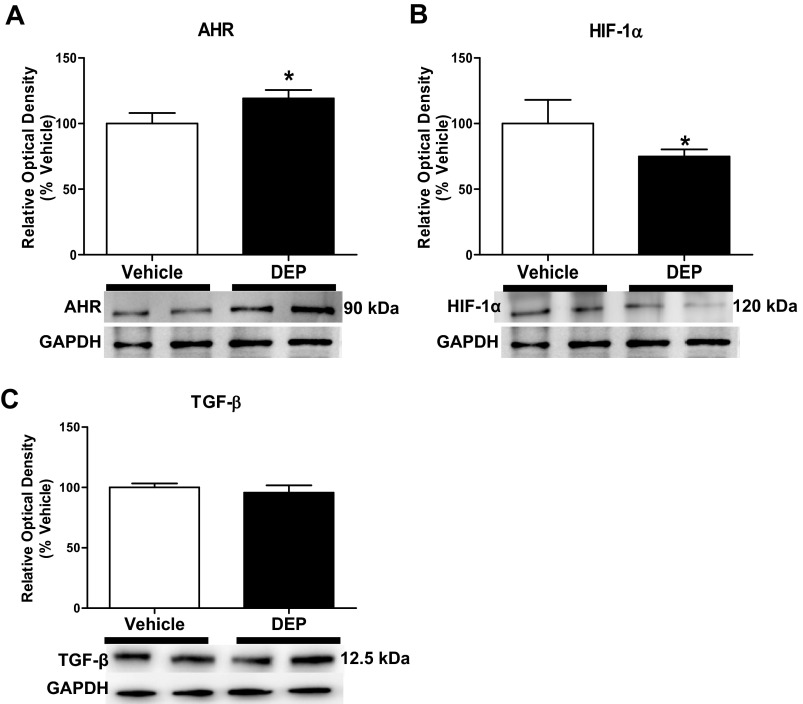

Exposure to DEP activates the AHR pathway.

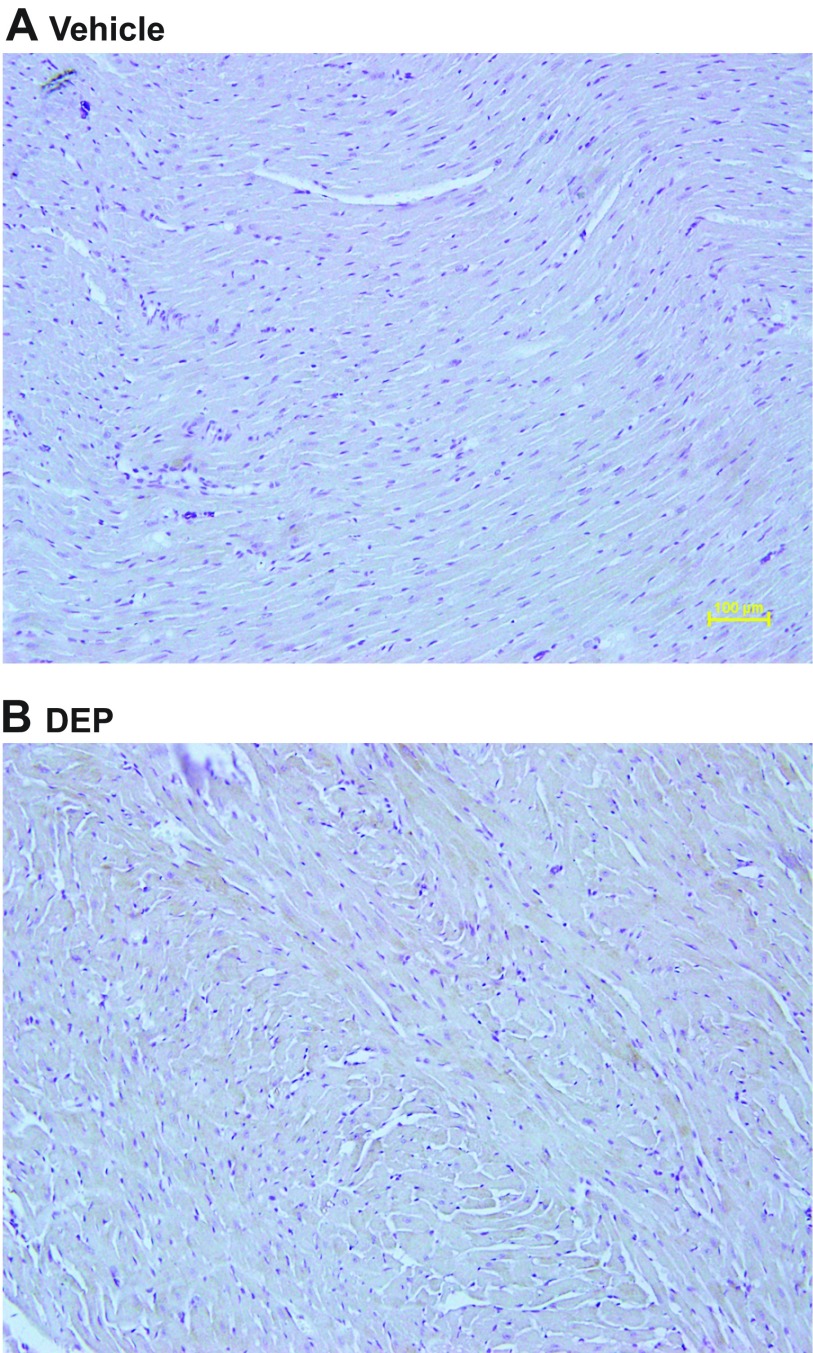

Exposure to DEP significantly increased the cardiac expression of AHR (19% increase; 90 kDa; Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemistry revealed increased CYP 1A1 expression in LV sections of rats treated with DEP (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

DEP increased cardiac expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR; A) and decreased hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α (B). Expression of the AHR, HIF-1α, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (C) in LV extracts by Western blot analysis (n = 5–6/group) is shown. Exposure to DEP for 5 wk induced a significant increase in the expression of AHR (A) and decrease in HIF-1α (B) relative to vehicle (*P < 0.05). There was no change in TGF-β expression. Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 4.

DEP exposure increased CYP 1A1 in LV. Representative immunohistochemistry of cytochrome P-450 (Cyp) 1A1 after 5 wk of vehicle (A) or DEP exposure (B). Darker areas represent positive Cyp 1A1 immunostaining.

Exposure to DEP attenuates the HIF-1α pathway.

DEP-exposed rats had a significant decrease in the cardiac expression of HIF-1α (26% decrease; ∼120 kDa; Fig. 3B); however, there was no difference in the cardiac expression of transforming growth factor-β (∼12.5 kDa; Fig. 3C). Assessment of cardiovascular disease markers using a Luminex multiplex array demonstrated that exposure to DEP significantly decreased cardiac VEGF (47% decrease; Table 3). These rats also exhibited significantly increased troponin T in the heart (16% increase; Table 3). There were no significant differences in IL-1β, IL-6, myeloperoxidase, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP)-1, or von Willebrand factor between groups.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular disease markers

| Vehicle | DEP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 4 | 4 | |

| IL-1β | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 0.30 |

| IL-6 | 25.9 ± 3.1 | 27.2 ± 3.8 | 0.40 |

| MPO | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.31 |

| PAI-1 | 372.9 ± 14.1 | 352.8 ± 6.4 | 0.12 |

| TIMP-1 | 269.6 ± 21.9 | 319.7 ± 22.2 | 0.077 |

| Troponin T | 53,120 ± 2,199 | 61,960 ± 3,067* | <0.05 |

| VEGF | 108.7 ± 17.0 | 63.8 ± 3.3* | <0.05 |

| vWF | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 0.12 |

Values are means ± SE in pg/mg protein; n, no. of animals. IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Statistical significance: P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

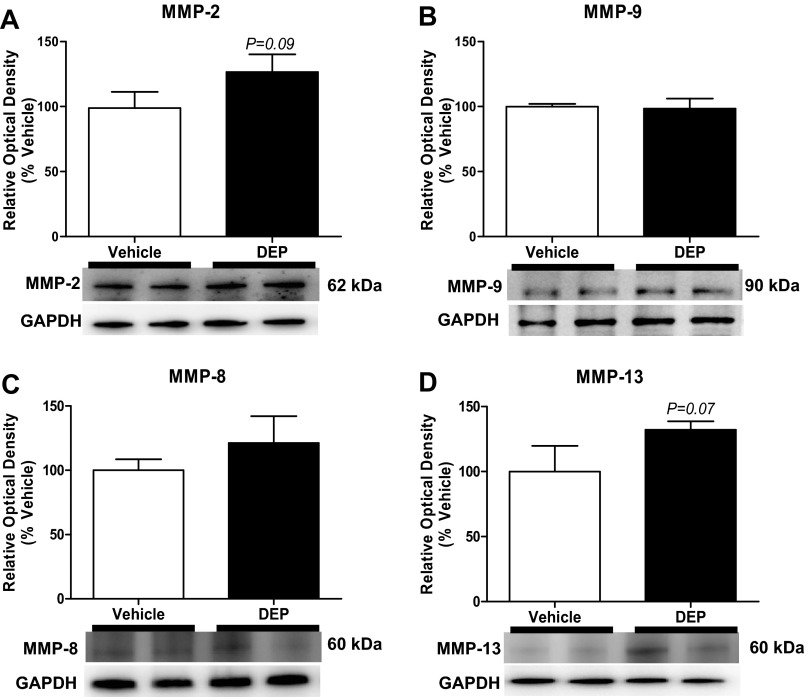

Exposure to DEP did not alter MMP expression.

There were no significant differences in the expression of MMP-9 (85 kDa), MMP-2 (63 kDa), MMP-8 (64 kDa), or MMP-13 (60 kDa) between the vehicle- and DEP-exposed rat hearts (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

DEP did not alter cardiac expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Expression of MMP-2, -9, -8, and -13 in LV extracts by Western blot analysis (n = 5–6/group) after 5 wk of treatment is shown. Values are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

It is well documented that exposure to PM can produce cardiac dysfunction; however, the mechanisms by which this occurs is unknown (12, 28, 35, 42). Very few have examined how heart function changes in response to particle exposure, with fewer examining the impact of particles on the structural components of the heart (35, 42). Therefore, the goal of our study was to assess the impact of DEP on cardiac function and the ventricular ECM. We found that DEP-exposed animals developed cardiac dysfunction after 5 wk exposure, which was associated with significant alterations in LV interstitial collagen.

Compared with vehicle exposure, rats exposed to DEP exhibited significant LV chamber dilation, accompanied by a decrease in posterior wall thickness. By LaPlace's Law, ventricular wall stress is directly related to cavity pressure times the radius and inversely related to the wall thickness. A disproportional change in any of these factors, such as an increased chamber radius or decreased wall thickness, can lead to increased stress on the ventricular wall, ultimately causing cardiac dysfunction (22). Hearts of DEP rats exhibited chamber dilation associated with wall thinning, as indicated by a decrease in the eccentric index (2 × LV wall thickness/LV chamber diameter), confirming eccentric dilation, a condition observed during decompensated volume overload heart failure (22). These findings are consistent with a study by Tankersley and colleagues (35) that demonstrated exposure to carbon black, a particle that has a carbon core analogous to that of DEP, resulted in similar eccentric LV dilation in senescent mice; however, there were no structural changes in middle-aged mice. Carbon black, unlike DEP, does not contain cardiotoxic PAHs (3, 37). This difference in the chemical composition of the particles may explain why chronic exposure to DEP degraded ventricular structure and function in our relatively healthy young animals.

The DEP-mediated alterations in structural integrity of the LV were accompanied by altered diastolic function, indicated by an increased EDP and decreased τ. Although there was no significant change in EDPVR (P = 0.09), a measure of ventricular compliance, rats exposed to DEP trended toward increased LV compliance. Exposure to DEP significantly reduced ESPVR and dP/dtmax vs. EDV, indicating that contractility was impaired in the DEP-exposed group. Gordon et al. (12) also demonstrated reduced contractility after 4 wk of exposure to DEP, as measured by increased QA intervals via radiotelemetry. Despite decreased contractility and diastolic dysfunction, CO and SV were not decreased and trended to increase. One possible explanation for the maintenance of CO and SV is that 5 wk of DEP exposure may have caused changes in the heart similar to those found in the early, compensated stages of cardiac remodeling (17). DEP exposure resulted in increased heart rate, which has several influences on cardiac function. Heart rate is a component of CO; therefore, the increase in heart rate may explain why DEP-treated animals maintained CO. In addition, heart rate affects relaxation rate, such that the increased heart rate accelerated relaxation, resulting in a decreased τ. These findings support a compensatory response to DEP exposure by heightened sympathetic drive. We speculate that prolonged exposure to DEP would lead to progressive LV eccentric dilation and further degradation of cardiac function.

Because DEP exposure resulted in eccentric LV dilation, we postulated that DEP disrupted myocardial collagen. The myocardial ECM plays a pivotal role in maintaining the structure of the heart. Cardiac structure is primarily regulated through the accumulation and degradation of collagen within the ECM (6, 27). Collagen turnover is tightly regulated under normal conditions; however, pathological stimuli can disrupt this regulation, resulting in a change of cardiac structure and ultimately function (10, 21, 34). Our study found that 5 wk of exposure to DEP caused a significant loss of myocardial collagen, providing a potential mechanism of the observed LV dilation and trend for increased LV compliance.

Exposure to DEP significantly increased the expression of AHR in the heart. Furthermore, DEP elicited increased expression of cardiac CYP 1A1, a biomarker for AHR activation (16). A prolonged activation of the AHR signaling pathway attenuates HIF-1α expression and its downstream signals, including VEGF (14, 19, 30, 31). Our data are in accord with these findings, as DEP-treated rats had significantly reduced cardiac HIF-1α and VEGF. Thackaberry and colleagues (36) demonstrated that both AHR and HIF-1α can induce changes in ventricular diameter and wall thickness, suggesting that these two pathways have a great impact on ventricular structure. Elevations in cardiac HIF-1α and VEGF are correlated with increased cardioprotection in several cardiac disorders, including pressure overload and myocardial infarction (7, 20, 33). Furthermore, blockade of HIF-1α and VEGF results in loss of protection, promoting heart failure (7, 20, 33). AHR activation induces a loss of collagen in various tissues (1, 25, 29, 38). Andreasen and colleagues (1) demonstrated that AHR activation significantly decreases collagen content during Zebra fish fin regeneration. Conversely, Corpechot and coworkers (8) demonstrated that HIF-1α promotes collagen production in hepatic stellate cells. However, the involvement of these pathways on myocardial collagen turnover is largely unknown.

AHR activation is also associated with increased expression of MMPs (1, 15, 18, 39). MMPs are ECM regulatory proteins that, upon activation, degrade collagen and other ECM components (34). Alterations in myocardial collagen are largely correlated to the balance between MMPs and their inhibitors (TIMPs), which can determine net collagen accumulation or degradation (34). In many cardiac diseases, increased MMP expression, including MMP-2, -9, -8, and -13, promote collagen degradation, leading to weakening of the ventricular wall and dilation (13, 34). Our studies showed no significant changes in MMPs or TIMP-1 at the 5-wk end point. However, in the DEP-treated animals, the expression of MMP-2 (P = 0.09) and MMP-13 (P = 0.07) tended to increase. In animal models of dilated cardiomyopathy, such as volume overload, MMP activity increases during the early compensatory stage, returns to normal levels, and is then further increased during decompensated heart failure (34). We predict that, although there was no change at this 5-wk time point, a longer exposure (weeks to months) may induce a significant increases in expression compared with vehicle. It is also possible that the loss of collagen observed in our studies was a result of an alternative pathway not observed in other cardiac diseases.

Wold and colleagues (42) demonstrated that exposure to concentrated PM 2.5, which contains particles from various sources, including traffic-related PM, resulted in alterations of the ventricular structure. In contrast to our findings of ventricular collagen loss, they found that PM exposure led to cardiac fibrosis. This divergence in our results may be due to differences in particle composition (traffic mixture PM vs. DEP), time and duration of exposure (6 h/day for 9 mo vs. 20 min/day for 5 wk), or species (mouse vs. rat). Most importantly, both studies demonstrated that PM exposure had a detrimental effect on cardiac structure and function, inducing remodeling similar to that observed in heart failure.

Our findings led us to conclude that exposure to DEP elicits eccentric LV dilation with systolic and diastolic dysfunction. In addition, exposure to DEP caused significantly increased cardiac AHR expression and attenuation of the HIF-1α pathway. Our data provide evidence that exposure to DEP induces ECM remodeling by impairing the accumulation of collagen, promoting increased degradation, which leads to a reduction in myocardial collagen, LV dilation, and dysfunction. Our data provide evidence that the AHR signaling pathway may play a critical role in this DEP-induced cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. Future studies could focus on the dose dependence of the cardiac injury and extend the protocol to assess the effects of chronic particulate exposure.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by the Louisiana Board of Regents through the Board of Regents Support Fund [no. LEQSF(2009-12)-RD-A-10; J. D. Gardner], the American Heart Association Greater Southeast Affiliate (no. 11GRNT7700002; J. D. Gardner), and National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (2P20RR-018766-09).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.M.B. and J.D.G. conception and design of research; J.M.B., K.A.C., M.C.E.H., and E.C.E.H. performed experiments; J.M.B., K.A.C., M.C.E.H., E.C.E.H., and J.D.G. analyzed data; J.M.B. and J.D.G. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.B., K.A.C., M.C.E.H., and J.D.G. prepared figures; J.M.B. and J.D.G. drafted manuscript; J.M.B. and J.D.G. edited and revised manuscript; J.D.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Kurt Varner, Kathleen McDonough, and Michael Levitzky for reviews and comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreasen EA, Mathew LK, Lohr CV, Hasson R, Tanguay RL. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation impairs extracellular matrix remodeling during zebra fish fin regeneration. Toxicol Sci 95: 215–226, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berk BC, Fujiwara K, Lehoux S. ECM remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. J Clin Invest 117: 568–575, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billiard SM, Timme-Laragy AR, Wassenberg DM, Cockman C, Di Giulio RT. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway in mediating synergistic developmental toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to zebrafish. Toxicol Sci 92: 526–536, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley JM, Nguyen JN, Fournett AC, Gardner JD. Cigarette smoke exacerbates ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in the volume overloaded heart. Microsc Microanal 18: 1–8, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC, Jr, Whitsel L, Kaufman JD. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121: 2331–2378, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45: 657–687, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai Z, Zhong H, Bosch-Marce M, Fox-Talbot K, Wang L, Wei C, Trush MA, Semenza GL. Complete loss of ischaemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mice with partial deficiency of HIF-1 alpha. Cardiovasc Res 77: 463–470, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corpechot C, Barbu V, Wendum D, Kinnman N, Rey C, Poupon R, Housset C, Rosmorduc O. Hypoxia-induced VEGF and collagen I expressions are associated with angiogenesis and fibrogenesis in experimental cirrhosis. Hepatology 35: 1010–1021, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Amato G, Cecchi L, D'Amato M, Liccardi G. Urban air pollution and climate change as environmental risk factors of respiratory allergy: an update. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 20: 95–102; quiz following 102, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner JD, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Effects of dietary phytoestrogens on cardiac remodeling secondary to chronic volume overload in femal rats. J Appl Physiol 99: 1378–1383, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner JD, Murray DB, Voloshenyuk TG, Brower GL, Bradley JM, Janicki JS. Estrogen attenuates chronic volume overload induced structural and fucntional remodeling in male rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H497–H504, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon CJ, Schladweiler MC, Krantz T, King C, Kodavanti UP. Cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses of unrestrained rats exposed to filtered or unfiltered diesel exhaust. Inhal Toxicol 24: 296–309, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunja-Smith Z, Morales AR, Romanelli R, JFW Jr. Remodeling of human myocardial collagen in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: role of metalloproteinases and pyridinoline cross-links. Am J Pathol 148: 1639–1648, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hankinson O. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 35: 307–340, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haque M, Francis J, Sehgal I. Aryl hydrocarbon exposure induces expression of MMP-9 in human prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett 225: 159–166, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu W, Sorrentino C, Denison MS, Kolaja K, Fielden MR. Induction of cyp1a1 is a nonspecific biomarker of aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation: results of large scale screening of pharmaceuticals and toxicants in vivo and in vitro. Mol Pharmacol 71: 1475–1486, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchinson KR, Jr, Stewart JA, Jr, Lucchesi PA. Extracellular matrix remodeling during the progression of volume overload-induced heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 564–569, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida M, Mikami S, Kikuchi E, Kosaka T, Miyajima A, Nakagawa K, Mukai M, Okada Y, Oya M. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway enhances cancer cell invasion by upregulating the MMP expression and is associated with poor prognosis in upper urinary tract urothelial cancer. Carcinogenesis 31: 287–295, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishimure R, Kawalami T, Ohsako S, Tohyama C. Dioxin-induced toxicity on vascular remodeling of the placenta. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 660–669, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, Sawyer D, Colucci W, Walsh K. Vascular endothelin growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension 47: 887–893, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jourdan-LeSaux C, Zhang J, Lindsey ML. Extracellular matrix roles during cardiac repair. Life Sci 87: 391–400, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kehat I, Molkentin JD. Molecular pathways underlying cardiac remodeling during pathophysiologicval stimulation. Circulation 122: 2727–2735, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kodavanti UP, Moyer CF, Ledbetter AD, Schladweiler MC, Costa DL, Hauser R, Christiani DC, Nyska A. Inhaled environmental combustion particles cause myocardial injury in the Wistar Kyoto rat. Toxicol Sci 71: 237–245, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodavanti UP, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Hauser R, Christiani DC, McGee J, Richards JR, Costa DL. Temporal association between pulmonary and systemic effects of particulate matter in healthy and cardiovascular compromised rats. J Toxicol Environ Health 65: 1545–1569, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kung T, Murphy KA, White LA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway as a regulatory pathway for cell adhesion and matrix metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 536–546, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li XY, Gilmore PS, Donaldson K, MacNee W. Free radical activity and pro-inflammatory effects of particulate air pollution (PM10) in vivo and in vitro. Thorax 51: 1216–1222, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsey ML, Mann DL, Entman ML, Spinale FG. Extracellular matrix remodeling following myocardial injury. Ann Med 35: 316–326, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahne S, Chuang GC, Pankey E, Kiruri L, Kadowitz PJ, Dellinger B, Varner KJ. Environmentally persistent free radicals decrease cardiac function and increase pulmonary artery pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1135–H1142, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathew LK, Andreasen EA, Tanguay RL. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation inhibits regenerative growth. Mol Pharmacol 69: 257–265, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mimura J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Functional role of AhR in the expression of toxicity effects by TCDD. Biochim Biophys Acta 1619: 263–268, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nie M, Blankenship AL, Giesy JP. Interactions between aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and hypoxia signaling pathways. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 10: 17–27, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc 3: 1422–1434, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiojima I, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Schiekofer S, Ito M, Liao R, Colucci W. Disruption of coordinated cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis contributes to the transition to heart failure. J Clin Invest 58: 26–37, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinale FG, Coker ML, Thomas CV, Walker JD, Mukherjee R, Hebbar L. Time-dependent changes in matrix metalloproteinase activity and expression during the progression of congestive heart failure: relation to ventricular and myocyte function. Circ Res 82: 482–495, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tankersley CG, Champion HC, Takimoto E, Gabrielson K, Bedja D, Misra V, El-Haddad H, Rabold R, Mitzner W. Exposure to inhaled particulate matter impairs cardiac function in senescent mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R252–R263, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thackaberry EA, Gabaldon DM, Walker MK, Smith SM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor null mice develop cardiac hypertrophy and increased hypoxia-inducible factor-1a in the absence of cardiac hypoxia. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2: 263–273, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Tiem LA, Di Giulio RT. AHR2 knockdown prevents PAH-mediated cardiac toxicity and XRE- and ARE-associated gene induction in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 254: 280–287, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomokiyo A, Maeda H, Fujii S, Monnouchi S, Wada N, Hori K, Koori K, Yamamoto N, Teramatsu Y, Akamine A. Alternation of extracellular matrix remodeling and apoptosis by activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway in human periodontal ligament cells. J Cell Biochem 113: 3093–3103, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villano CM, White LA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor-signaling pathway and tissue remodeling: insights from the zebrafish (Danio rerio) model system. Toxicol Sci 92: 1–4, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voloshenyuk TG, Gardner JD. Estrogen improves TIMP-MMP balance and collagen distribution in volume-overloaded hearts of ovariectomized females. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R686–R693, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker B, Jr, Mouton CP. Environmental influences on cardiovascular health. J Natl Med Assoc 100: 98–102, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wold LE, Ying Z, Hutchinson KR, Velten M, Gorr MW, Velten C, Youtz DJ, Wang A, Lucchesi PA, Sun Q, Rajagopalan S. Cardiovascular remodeling in response to long-term exposure to fine particulate matter air pollution. Circ Heart Fail 5: 452–461, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]