Update to: European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.231; published online 26 January 2011

1. DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS

1.1 Name of the disease (synonyms)

Complete or incomplete Achromatopsia, rod monochromatism, rod monochromacy, complete or incomplete colour blindness, pingelapese blindness.

1.2 OMIM# of the disease

ACHM2 216900, ACHM3 262300, ACHM4 139340, ACHM5 613093, RCD3A/ACHM5 610024.

1.3 Name of the analysed genes or DNA/chromosome segments

CNGB3, Chr. 8q21-q22

CNGA3, Chr. 2q11

GNAT2, Chr. 1p13

PDE6C, Chr. 10q24

PDE6H, Chr. 12p12.3

1.4 OMIM# of the gene(s)

CNGA3 [600053], protein: cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel, alpha 3

CNGB3 [605080], protein: cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel, beta 3

GNAT2 [139340], protein: guanine nucleotide-binding protein, alpha-transducing activity polypeptide 2

PDE6C [600827], protein: phosphodiesterase 6C, cGMP-specific, cone alpha-prime

PDE6H [601190], protein: phosphodiesterase 6 H, cGMP-specific, gamma

1.5 Mutational spectrum

Missense mutations, nonsense mutations, splice mutations, small deletions and insertions.

1.6 Analytical methods

Genomic sequencing of coding exons and flanking intronic sequences.

1.7 Analytical validation

Confirmation of mutation in an independent biological sample of the index case and/or in an affected subject; segregation analysis in the parents of the index patient.

1.8 Estimated frequency of the disease (incidence at birth (‘birth prevalence') or population prevalence)

1:30 000–1:50 000.1

1.9 If applicable, prevalence in the ethnic group of investigated person

Unknown.

1.10 Diagnostic setting

Comment: As penetrance is 100% and as disease is present from birth, the test is not used for predictive testing.

2. Test characteristics

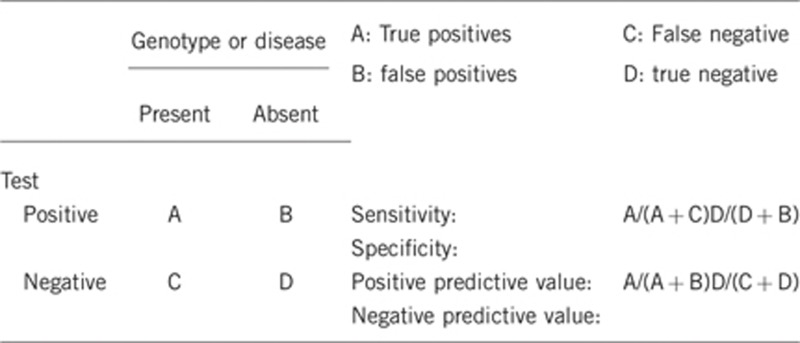

2.1 Analytical sensitivity

(proportion of positive tests if the genotype is present)

Nearly 100%.

2.2 Analytical specificity

(proportion of negative tests if the genotype is not present)

Above 95%.

Assuming a complete screening of all genes.

Variants of unknown significance might be re-classified as deleterious a posteriori.

2.3 Clinical sensitivity

(proportion of positive tests if the disease is present)

The clinical sensitivity can be dependent on variable factors such as age or family history. In such cases a general statement should be given, even if a quantification can only be made case by case.

It is 75–90% (refs 2, 3, 4) depending on the population—there is evidence for further genetic heterogeneity.

2.4 Clinical specificity

(proportion of negative tests if the disease is not present)

The clinical specificity can be dependent on variable factors such as age or family history. In such cases a general statement should be given, even if a quantification can only be made case by case.

Above 95%.

2.5 Positive clinical predictive value

(lifetime risk to develop the disease if the test is positive)

Although clinical expression can vary (complete and incomplete achromatopsia, rarely cone dystrophy and macular degeneration), clinical expression is expected to be 100% penetrant.

2.6 Negative clinical predictive value

(Probability not to develop the disease if the test is negative)

Assume an increased risk based on family history for a non-affected person. Allelic and locus heterogeneity may need to be considered.

Index case in that family had been tested:

Although mutations in CNGA3, CNGB3, GNAT2, PDE6C and PDE6H are responsible for the majority of ACHM cases, further genetic heterogeneity is expected. Yet as achromatopsia is a congenital disorder, disease is evident early.

Index case in that family had not been tested:

This approach cannot be supported.

3. Clinical utility

3.1 (Differential) diagnostics: The tested person is clinically affected

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘A' was marked)

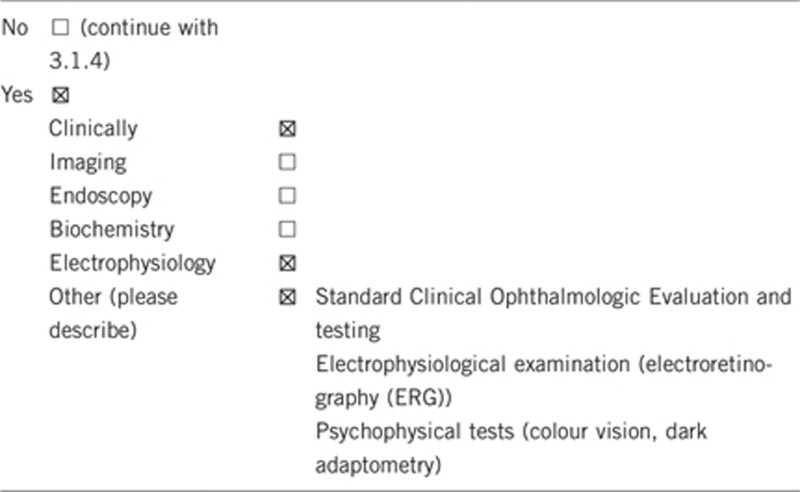

3.1.1 Can a diagnosis be made other than through a genetic test?

3.1.2 Describe the burden of alternative diagnostic methods to the patient

Initial clinical and electrophysiological investigations are always necessary before molecular genetic analysis is prescribed. However, clinical investigations are sometimes incomplete in young children (approximate visual acuity, ERG recorded with conjunctival electrodes and/or part field stimulation). Complete clinical investigations and ERG recording may require general anaesthesia.

3.1.3 How is the cost effectiveness of alternative diagnostic methods to be judged?

Clinical and electrophysiological testing in young children may require anaesthesia and hospitalization.

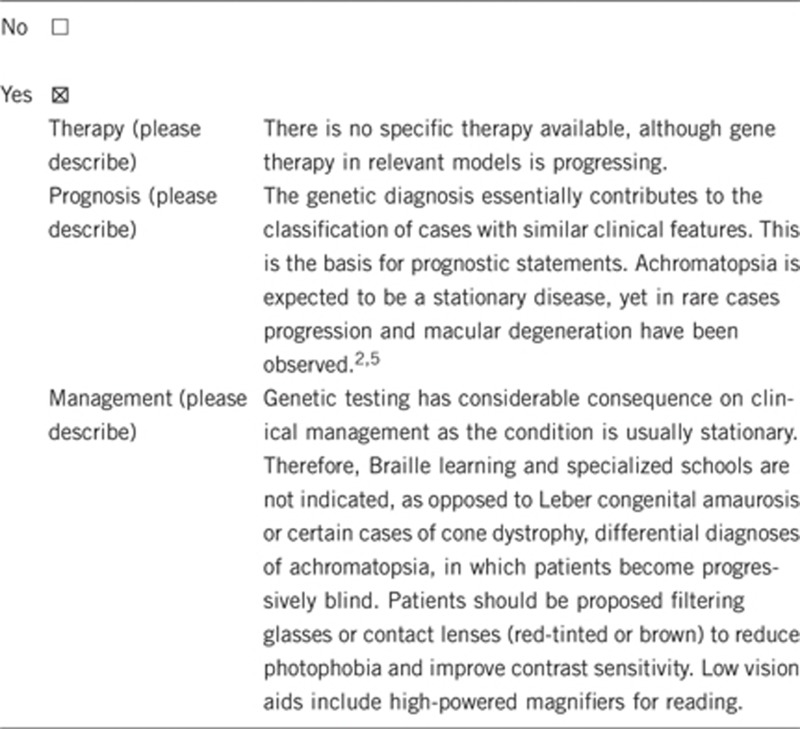

3.1.4 Will disease management be influenced by the result of a genetic test?

3.2 Predictive setting: the tested person is clinically unaffected but carries an increased risk based on family history

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘B' was marked)

3.2.1 Will the result of a genetic test influence lifestyle and prevention?

If the test result is positive (please describe): genetic analysis can guide prospective parents concerned about the risk of having affected children and will help in management of the disease in affected patients (see 3.1.4).

If the test result is negative (please describe): this will lead to reconsideration of the clinical diagnosis. The diagnosis of achromatopsia will therefore be either confirmed, suggesting a rare genetic form (genetic heterogeneity) for which the causative gene remains unknown, or invalidated and re-directed to, for example, blue cone monochromacy.

3.2.2 Which options in view of lifestyle and prevention does a person at-risk have if no genetic test has been done (please describe)?

Regular ophthalmological follow-up examination.

3.3 Genetic risk assessment in family members of a diseased person

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘C' was marked)

3.3.1 Does the result of a genetic test resolve the genetic situation in that family?

Yes, autosomal recessive inheritance if genotype defined.

3.3.2 Can a genetic test in the index patient save genetic or other tests in family members?

No.

3.3.3 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a predictive test in a family member?

Yes.

3.4 Prenatal diagnosis

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘D' was marked)

3.4.1 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a prenatal diagnostic?

Genetic counselling is mandatory. Prenatal diagnosis is increasingly asked for by at-risk couples and the use of prenatal diagnostic testing varies with national/ethic customs.

4. IF APPLICABLE, FURTHER CONSEQUENCES OF TESTING

Please assume that the result of a genetic test has no immediate medical consequences. Is there any evidence that a genetic test is nevertheless useful for the patient or his/her relatives? (Please describe).

Correct diagnosis has implications on education and professional career choices (low vision).

Parents are given accurate information on the cause of the disease, progression and recurrence risk.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by EuroGentest, an EU-FP6 supported NoE, contract number 512148 (EuroGentest Unit 3: ‘Clinical genetics, community genetics and public health', Workpackage 3.2).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Francois J. Heredity in Ophthalmology. CV Mosby: St. Louis; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Wissinger B, Gamer D, Jagle H, et al. CNGA3 mutations in hereditary cone photoreceptor disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:722–737. doi: 10.1086/323613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl S, Varsanyi B, Antunes GA, et al. CNGB3 mutations account for 50% of all cases with autosomal recessive achromatopsia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:302–308. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiadens AA, Slingerland NW, Roosing S, et al. Genetic etiology and clinical consequences of complete and incomplete achromatopsia Ophthalmology 20091161984–1989.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiadens AA, Roosing S, Collin RW, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the achromatopsia genes CNGA3 and CNGB3 in progressive cone dystrophy. Ophthalmology 2010117825–830.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]