Abstract

A meta-analysis was conducted to explore the risk for cardio-metabolic abnormalities in drug naïve, first-episode and multi-episode patients with schizophrenia and age- and gender- or cohort-matched general population controls. Our literature search generated 203 relevant studies, of which 136 were included. The final dataset comprised 185,606 unique patients with schizophrenia, and 28 studies provided data for age- and gender-matched or cohort-matched general population controls (n=3,898,739). We found that multi-episode patients with schizophrenia were at increased risk for abdominal obesity (OR=4.43; CI=2.52-7.82; p<0.001), hypertension (OR=1.36; CI=1.21-1.53; p<0.001), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (OR=2.35; CI=1.78-3.10; p<0.001), hypertriglyceridemia (OR=2.73; CI=1.95-3.83; p<0.001), metabolic syndrome (OR=2.35; CI=1.68-3.29; p<0.001), and diabetes (OR=1.99; CI=1.55-2.54; p<0.001), compared to controls. Multi-episode patients with schizophrenia were also at increased risk, compared to first-episode (p<0.001) and drug-naïve (p<0.001) patients, for the above abnormalities, with the exception of hypertension and diabetes. Our data provide further evidence supporting WPA recommendations on screening, follow-up, health education and lifestyle changes in people with schizophrenia.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, cardio-metabolic abnormalities, metabolic syndrome, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, screening, health education, lifestyle changes

A number of studies have demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia have an excess mortality, measured by a standardized mortality ratio that is two or three times that seen in the general population (1-11). This translates into 13-20 years of shortened life expectancy, a gap that has widened in recent decades (11-13).

It is well known that some of this excess mortality is due to suicide, but the majority is related to natural causes, such as cancer, respiratory diseases and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (13-15). Premature mortality from CVD is commonly attributed to low socio-economic status (e.g., poverty, poor education) (8), behavioural factors (e.g., alcohol and substance abuse, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating patterns) (16-23), and management factors (e.g., side effects of antipsychotic and concomitant medication use, fragmentation of physical and mental health care, disparities in quality of medical care) (24-28).

In order to help clinicians to identify and focus more on patients at increased risk for CVD, the concept of metabolic syndrome (MetS) has been introduced. MetS is defined by a combination of abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, elevated triglycerides and hyperglycemia (29-33). In the general population, these clustered risk factors have been associated with the development of CVD (29-33).

Although several definitions have been proposed for MetS, the most often cited are those formulated by the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), i.e., the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP-III) and adapted ATP-III criteria (ATP-III-A) (34,35), by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (36), and by the World Health Organization (WHO) (37). These definitions share similar diagnostic thresholds. However, abdominal obesity is central to the IDF definition, with provision of specific ethnic thresholds for waist circumference (38), while it is not a mandatory NCEP/ATP MetS criterion.

As a prevalent condition and a predictor of CVD across racial, gender and age groups, MetS provides a unique opportunity for identifying high-risk populations and preventing the progression of some of the major causes of morbidity and mortality (29-33).

In a previous meta-analysis (39), we demonstrated that almost one in three of unselected patients with schizophrenia meet criteria for MetS, one in two patients are overweight, one in five appear to have significant hyperglycemia (sufficient for a diagnosis of pre-diabetes) and at least two in five have lipid abnormalities. We also found a significantly lower cardio-metabolic risk in early schizophrenia than in chronic schizophrenia. Both diabetes and pre-diabetes appear uncommon in the early illness stages, particularly in drug naïve patients (40).

To the best of our knowledge, meta-analytic data comparing the cardio-metabolic risk in patients with schizophrenia across different stages (unmedicated, first-episode, multi-episode) versus matched healthy controls are currently lacking. Such data could raise awareness of conditions that cause a significant burden of morbidity and mortality, and thereby help motivate preventive strategies and adherence to recommended therapies.

The primary aim of the current meta-analysis therefore was to compare the risk for MetS, abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes in unmedicated, first-episode, and multi-episode patients with schizophrenia versus healthy age- and gender- or cohort-matched controls. We also updated comparisons in MetS, abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes risks between unmedicated, first-episode, and multi-episode patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard (41). The focus was on patients with schizophrenia, irrespective of age and clinical setting (inpatient, outpatient or mixed).

Inclusion criteria were: a DSM-IV-TR (42) or ICD-10 (43) diagnosis of schizophrenia (with or without related psychoses) and a MetS diagnosis according to non-modified ATP-III (34), ATP-III-A (35), IDF (36) or WHO (37) standards. We included case-control studies, prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and comparisons of study populations with age standardization. For comparison with healthy controls, only age- and gender-matched or cohort-matched studies were included. In the case of multiple publications from the same study, only the most recent paper with the largest sample was included.

Excluded were studies using non-standardized diagnoses of schizophrenia and/or MetS, limited to patients with known CVD, or limited to children and adolescents.

Two independent reviewers (DV and ADH) searched Medline, PsycINFO, Embase and CINAHL from database inception to March 1, 2013. The key word “schizophrenia” was cross-referenced with the following terms: “metabolic syndrome” OR “obesity” OR “lipids” OR “cholesterol” OR “hypertension” OR “diabetes”. Manual searches were conducted using the reference lists from recovered articles. Prevalence rates of MetS, abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes for patients and controls were abstracted by the same two independent reviewers. We also contacted authors for additional data and received information from 21 research groups (see Acknowledgements).

To examine the homogeneity of the effect size distribution, a Q-statistic was used (44). When the Q-statistic is rejected, the effect size distribution is not homogeneous, implying that the variability in the prevalence rates of the cardio-metabolic abnormalities between studies is larger than can be expected based on sampling error.

The effect size used for the prevalence rate of all cardio-metabolic abnormalities under research was the proportion, but all analyses were performed converting proportions into logits. Logits are preferred over proportions because the mean proportion across studies underestimates the size of the confidence interval around the mean proportion (due to compression of the standard error as p approaches 0 or 1) and overestimates the degree of heterogeneity across effect sizes. This is especially the case when the observed proportions are <0.2 or >0.8 (45). However, for ease of interpretation, all final results were back converted into proportions. In case of heterogeneity and when information about moderator variables was available, we opted for a mixed effects model. In these analyses, several study characteristics were incorporated, including mean age of the study sample, type of treatment setting (outpatient versus inpatient), medication status (medicated versus drug-naïve), and disease status (first episode versus not first episode). A random effects model was adopted when the Q-statistics indicated that there was heterogeneity and moderator variables were lacking.

Lastly, we pooled data from individual studies to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and used Wald tests to statistically compare the prevalence of cardio-metabolic abnormalities between patients with schizophrenia (unmedicated, first-episode, multi-episode) and age-matched general population control subjects.

Results

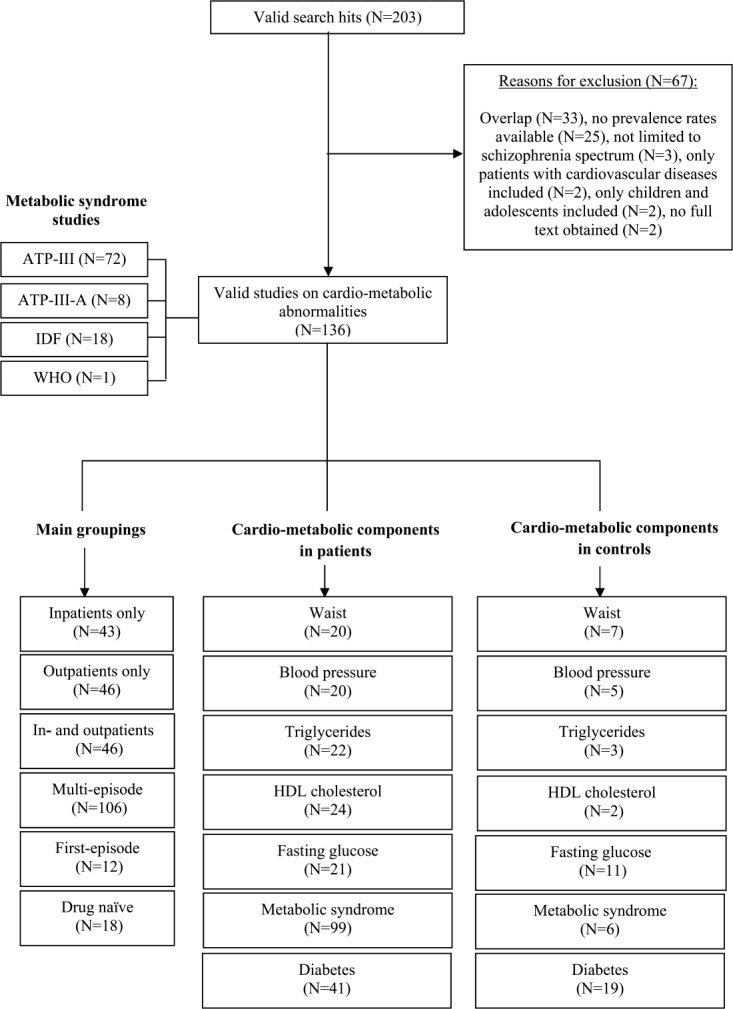

Our search generated 203 relevant studies, of which 136 (46-181) were included. Reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Quality of reporting of meta-analyses (Quorom) search results. ATP-III – Adult Treatment Panel III; ATP-III-A – Adult Treatment Panel III, adapted; IDF – International Diabetes Federation; WHO – World Health Organization; HDL – high-density lipoprotein

The final dataset comprised 185,606 unique patients with schizophrenia. Forty-three studies were conducted amongst inpatients (n=12,499; 59.7% male; mean age = 38.9 years), 46 in outpatient settings (n=12,469; 61.0% male; mean age = 38.6 years) and 46 in mixed samples (n=160,638; 62.0% male; mean age = 38.7 years). Twelve studies examined individuals who were in their first episode (n=2,192; 62.0% male; mean age = 28.7 years); 18 studies examined drug-naïve patients (n=1,104; 61.0% male; mean age = 30.7 years).

In 28 studies, age and gender head-to-head or cohort-matched general population control data (n=3,898,739) were available (47,51,55,57,60,61,63,74,78,89,93,94,103,117,119,122,134,135,138,148,150,152,156,158,165,171,176). There were, however, insufficient data to compare the prevalence of cardio-metabolic abnormalities of first-episode and/or drug-naïve patients with age and gender head-to-head or cohort-matched general population control data.

The Q-statistic indicated that the distribution of the prevalence of abdominal obesity across individual studies was not homogeneous (Q(51)=994.4; p<0.001). Compared with multi-episode patients (N=46; n=19,043; mean age = 38.6 years), drug-naïve patients (N=5; n=444; mean age = 28.0 years) had a significantly reduced risk for abdominal obesity: 50.0% (95% CI=46.9%-53.1%) versus 16.6% (95% CI=11.2%-24.0%) (p<0.001). Compared with matched general population control subjects (n=868), multi-episode patients (n=6,632) had a significantly increased risk of abdominal obesity when pooling data of the individual studies (N=5) (OR=4.43; CI=2.52-7.82; p<0.001). There were insufficient data to compare first-episode and drug-naïve patients with general population controls.

The Q-statistic indicated that the distribution of the prevalence of hypertension across individual studies was not homogeneous (Q(56)=12262.5; p<0.001). Fifty-seven studies reported on hypertension (n=113,286; 61.9% male; mean age = 38.8 years). The prevalence of hypertension was 36.3% (95% CI=30.9%-42.1%). Multi-episode patients (37.3%, 95% CI=32.5%-42.3%; N=47; n=112, 167; 62.0% male; mean age = 41.7 years) did not differ (p=0.64) from first-episode (41.1%, 95% CI=20.7%-65.1%; N=1; n=488; 60.0% male; mean age = 26.6 years) and drug-naïve (31.6%, 95% CI=21.3%-44.0%; N=8; n=631; 63.0% male; mean age = 28.3 years) patients. Compared with matched general population control subjects (n=732,965), multi-episode patients (n=2,410) had a significantly increased risk of hypertension when pooling data of the individual studies (N=4) (OR=1.36; CI=1.21-1.53; p<0.001).

The Q-statistic indicated that the distribution of the prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia across individual studies was not homogeneous (Q(57)=1641.2; p<0.001). Fifty-eight studies reported on hypertriglyceridemia (n=20,996; 61.0% male; mean age = 38.5 years). The prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia was 34.5% (95% CI=30.7%-38.5%). There was no significant difference between drug-naïve (N=7; n=538; 60.8% male; mean age = 27.6 years) and first-episode (N=5; n=1,150; 58.0% male; mean age = 30.4 years) patients, with a prevalence of 23.3% (95% CI=15.4%-33.6%) and 10.5% (95% CI=5.8%-18.2%), respectively. In contrast, multi-episode patients (N=46; n=19,152; 61.2% male; mean age = 41.1 years) had a significantly increased prevalence (39.0%, 95% CI=9.9%-44.0%) compared to drug-naïve and to first-episode patients (p<0.001). Compared with matched general population control subjects (n=6,016), multi-episode patients (n=647) had a significantly increased risk of hypertriglyceridemia (OR=2.73; CI=1.95-3.83; p<0.001) (N=2).

The Q-statistic indicated that the distribution of the prevalence of abnormally low HDL cholesterol levels across individual studies was not homogeneous (Q(57)=1118.4; p<0.001). Fifty-eight studies reported on low HDL cholesterol levels (n=20,907; 61.2% male; mean age = 38.6 years). The prevalence rate was 37.5% (95% CI=34.3%-40.8%). There was no significant difference between drug-naïve (N=7; n=538; 61.7% male; mean age = 27.5 years) and first-episode (N=5; n=1,306; 57.2% male; mean age = 28.5 years) patients, with 24.2% (95% CI=17.4%-32.5%) and 16% (95% CI=10.4%-23.9%), respectively. In contrast, multi-episode patients (N=46, n=19,063; 61.5% male; mean age = 41.2 years) had a significantly increased prevalence (41.7%, 95% CI=38.3%-45.2%) compared to drug-naïve and to first-episode patients (p<0.001). Compared with general population control subjects (n=6,016), multi-episode patients (n=647) had a significantly higher risk for low HDL cholesterol levels (OR=2.35; CI=1.78-3.10; p<0.001) (N=2).

The Q-statistic indicated that the distribution of the MetS prevalence across individual studies was not homogeneous (Q(106)=1470.4; p<0.001). One hundred and seven studies reported on MetS (n=28,729; 60.6% male; mean age = 38.8 years). The prevalence was 31.1% (95% CI=28.9%-33.4%). There was no significant difference between drug-naïve (N=11; n=733; 60.0% male; mean age = 29.2 years) and first-episode (N=6; n=1,039; 60.1% male; mean age = 30.1 years) patients, with 10.0% (95% CI=7.0%-14.2%) and 15.9% (95% CI=10.5%-23.3%), respectively. In contrast, multi-episode patients (N=46; n=26,957; 60.6% male; mean age = 38.8 years) had a significantly increased prevalence (34.2%, 95% CI=31.9%-36.6%) compared to drug-naïve and to first-episode patients (p=0.007). Compared with age- and gender- or cohort-matched general population control subjects (n=6,632), multi-episode medicated patients (n=868) had a significantly higher risk for MetS (OR=2.35; CI=1.68-3.29; p<0.001) (N=4).

The Q-statistic indicated that the distribution of the prevalence of diabetes across individual studies was not homogeneous (Q(42)=3718.8; p<0.001). Forty-one studies reported on diabetes (n=161,886; 61.3% male; mean age=40.1 years). The prevalence was 9.0% (95%CI=7.3%-11.1%). Multi-episode patients (9.5%, 95% CI=7.3%-12.2%; N=29; n=116,751; 60.0% male; mean age = 43.8 years) did not differ (p=0.56) from first-episode (8.7%, 95% CI=5.6%-13.3%; N=5; n=1033; 61.0% male; mean age = 32.4 years) and drug-naïve (6.4%, 95% CI=3.2%-12.5%; N=5; n=346; 66.0% male; mean age = 29.2 years) patients. Compared with matched general population control subjects (n=3,891,899), multi-episode patients (n=106,720) had a significantly higher risk for diabetes (OR=1.99; CI=1.55-2.54; p<0.001) (N=15).

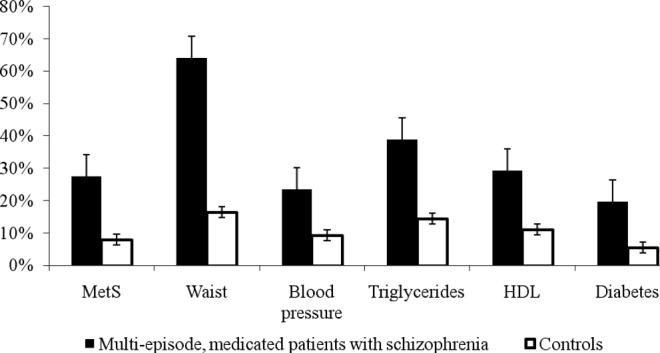

Figure 2 presents an overview of the mean prevalence for all investigated cardio-metabolic parameters in multi-episode medicated patients with schizophrenia versus healthy controls.

Figure 2.

Overview of the prevalence of cardio-metabolic abnormalities in multi-episode medicated patients with schizophrenia versus age- and gender- or cohort-matched controls. MetS – metabolic syndrome; HDL – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to demonstrate that medicated multi-episode patients with schizophrenia are at a more than fourfold increased risk for abdominal obesity compared to age- and gender- or cohort-matched general population controls (OR=4.43). The odds ratio of risk for low HDL cholesterol (OR=2.35), MetS (OR=2.35) and hypertriglyceridemia (OR=2.73) was more than double. Compared to general population controls, multi-episode patients with schizophrenia also have almost twice the risk (by odds) for diabetes (OR=1.99), while the odds for hypertension was 1.36. Our data also confirm previous findings (40) that chronic, medicated patients with schizophrenia have a significantly increased risk for developing cardio-metabolic abnormalities compared with first-episode and drug-free patients. No significant differences in blood pressure and diabetes between chronic, medicated, first-episode and drug-free patients were, however, found. A possible reason might be that we were not able to control for use of antihypertensive and glucose lowering drugs.

We wish to acknowledge some limitations in our primary database that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, there was considerable heterogeneity, which could only be partly controlled by stratification for disease stage. Second, there was a very limited number of studies comparing first-episode and unmedicated patients with controls and hence these analyses were not possible. Third, there was marked variation in the sample size of the included studies. Fourth, we were not able to adjust for type and duration of antipsychotic treatment.

Next to a low socio-economic status (8), behavioural factors (16-23), side effects of antipsychotic and concomitantly used medications, and fragmentation of health care (24-28), various inflammatory processes could contribute to the increased cardio-metabolic risk observed in patients with schizophrenia (182). In a recent review, Steiner et al (183) highlighted the alterations in the immune system of patients with schizophrenia. Increased concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and transforming growth factor-beta appear to be state markers, whereas increased levels of IL-12, interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and soluble IL-2 receptor appear to be trait markers of schizophrenia. The mononuclear phagocyte system and microglial activation are also involved in the early course of the disease. The mechanisms whereby inflammatory mediators initiate a wide range of cardio-metabolic abnormalities are being elucidated, but the causes of the vulnerability to chronic low-grade inflammation are still speculative, especially as increased body mass index (BMI) and obesity are in and of themselves associated with increased inflammation (182,183).

Since patients with schizophrenia are a high-risk group for developing cardio-metabolic abnormalities, they should be routinely screened for CVD risk factors at key stages (184,185). This can be achieved by establishing a risk profile based on consideration of cardio-metabolic factors (abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, hyperglycemia), but also through consideration of a patient's personal and family history, covering diabetes, hypertension, CVD (myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident, including age at onset) and behavioural factors (e.g., poor diet, smoking and physical inactivity) (186-189). This risk profile should afterwards be used as a basis for ongoing monitoring, treatment selection and management.

Guidelines from the WPA (189) recommend that monitoring should be conducted at the initial presentation and before the first prescription of antipsychotic medication and (for patients with normal baseline tests) repeated at 6 weeks (for blood glucose) and 12 weeks after initiation of treatment, and at least annually thereafter for all parameters. The 6-week blood sugar assessment to rule out precipitous diabetes onset has, however, been recommended in Europe, but not in the US (189). In light of the high rates of metabolic abnormalities observed in all settings, we propose that minimum monitoring should include waist circumference. Optimal monitoring should also include fasting glucose, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c). HbA1c has the advantage of not requiring a fasting sample in those taking antipsychotic medication and was recently shown to identify patients with pre-diabetes and diabetes not captured by assessments of fasting glucose (190,191). Moreover, a recent study found that the optimal testing protocol to detect diabetes was a HbA1c threshold ≥5.7%, followed by conventional testing with an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and fasting blood glucose in patients who test positive (192).

Psychiatrists should, regardless of the medication prescribed, monitor and chart waist circumference of every patient with schizophrenia at every visit, and should encourage patients to monitor and chart their own weight (189). The WPA (189) states that these physical health monitoring tests are simple, easy to perform and inexpensive, and therefore can/should be implemented in the health care systems of developed as well as developing countries. In a recent study (193), we demonstrated that the optimal clinical predictors of diabetes in severe mental illness were BMI, waist/hip ratio, height, age, and duration of illness. No single clinical factor was able to accurately rule in a diagnosis of diabetes, but three variables could be used as an initial screening (rule-out) test, namely BMI, waist/hip ratio and height. A BMI <30 had a 92% negative predictive value in ruling out diabetes. Of those not diabetic, 20% had a BMI <30. It is therefore recommended that clinicians use HbA1, fasting glucose and OGTT when testing for diabetes in patients with schizophrenia, especially high risk patients, based on the above clinical factors.

In addition to optimal screening and follow-up, the WPA (189) recommends that psychiatrists, physicians, physical therapists and other members of the multidisciplinary team should help educate and motivate patients with schizophrenia to improve their lifestyle through use of behavioural interventions, including smoking cessation, dietary measures, and exercise. In two recent, multi-centre studies (194,195) we showed that many, although not all, patients with schizophrenia were either unaware of the need to change their lifestyle or did not possess the knowledge and skills required to make appropriate lifestyle changes. Therefore, it is useful that family members and caregivers be offered education regarding the increased cardio-metabolic risk of patients with schizophrenia and ways to mitigate this risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following researchers for providing additional data: T. Heiskanen and H. Koponen, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland; R. Chengappa, University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; T. Cohn, University of Toronto, Canada; J. Meyer, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA; J. Crilly and J.S. Lamberti, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA; P. Mackin, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; S. Tirupati, James Fletcher Hospital, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia; T. Sanchez-Araña Moreno, Psychiatry Hospital de la Merced, Osuna, Spain; P.J. Teixeira, Instituto de Previdência dos Servidores do Estado de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil; G.J. L'Italien, Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Wallingford, CT, USA; V. Ellingrod, University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Hung-Wen Chiu, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan; D. Cohen, Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg Noord-Holland Noord, The Netherlands; H. Mulder, Utrecht University and Wilhelmina Hospital Assen, The Netherlands; J.K. Patel, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA; K. Taxis, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; B. Vuksan, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, Croatia; R.K. Chadda, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, India; L. Pina, Psychiatry, Gregorio Marañon General Universitary Hospital, Madrid, Spain; J. Rabe-Jablonska and T. Pawelczyk, Medical University of Lodz, Poland; D. Fraguas, University Hospital of Albacete, Albacete, Spain.

References

- 1.Allebeck P. Schizophrenia: a life-shortening disease. Schizophr Bull. 1989;15:81–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36:239–45. doi: 10.1177/070674379103600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casadebaig F, Philippe A. Mortality in schizophrenia patients. 3 years follow-up of a cohort. Encephale. 1999;25:329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, et al. Time trends in schizophrenia mortality in Stockholm county, Sweden: cohort study. BMJ. 2000;321:483–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rössler W, Salize HJ, van Os J, et al. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capasso RM, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM, et al. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950–2005. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study) Lancet. 2009;374:620–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, et al. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:116–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healy D, Le Noury J, Harris M, et al. Mortality in schizophrenia and related psychoses: data from two cohorts, 1875–1924 and 1994–2010. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koola MM, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, et al. Alcohol and cannabis use and mortality in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:987–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, et al. Considering a frame of reference for physical activity research related to the cardiometabolic risk profile in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beary M, Wildgust HJ. A critical review of major mortality risk factors for all-cause mortality in first-episode schizophrenia: clinical and research implications. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(Suppl. 5):52–61. doi: 10.1177/0269881112440512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildgust HJ, Beary M. Are there modifiable risk factors which will reduce the excess mortality in schizophrenia? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(Suppl. 4):37–50. doi: 10.1177/1359786810384639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Maurissen K, et al. Physical activity participation, functional exercise capacity and self-esteem in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2011;18:222–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vancampfort D, Probst M, Sweers K, et al. Relationships between obesity, functional exercise capacity, physical activity participation and physical self perception in people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:423–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vancampfort D, Probst M, Scheewe T, et al. Relationships between physical fitness, physical activity, smoking and metabolic and mental health parameters in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vancampfort D, Probst M, Knapen J, et al. Associations between sedentary behaviour and metabolic parameters in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell AJ, Lord O. Do deficits in cardiac care influence high mortality rates in schizophrenia? A systematic review and pooled analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(Suppl. 4):69–80. doi: 10.1177/1359786810382056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenback D, Pijl B, Smeets H, et al. All-cause mortality and medication risk factors in schizophrenia: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:31–5. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31823f3c43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:733–59. doi: 10.2165/11634500-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manu P, Correll CU, van Winkel R, et al. Prediabetes in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:460–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8:114–2. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurdyak P, Vigod S, Calzavara A, et al. High mortality and low access to care following incident acute myocardial infarction in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;142:52–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119:812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayturan O, Tuzcu EM, Lavoie A, et al. The metabolic syndrome, its component risk factors, and progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:478–84. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Expert Panel on Detection and Evaluation of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels RS, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw P. The metabolic syndrome, a new worldwide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization Consultation. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:306–18. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, De Herdt A, et al. Is the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:295–305. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision – DSM-IV-TR. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders – Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee S, Decina P, Bocola, et al. Diabetes mellitus in schizophrenic patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon L, Weiden P, Delahanty J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in national schizophrenia samples. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:903–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Addington J, Mansley C, Addington D. Weight gain in first-episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:272–6. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heiskanen T, Niskanen L, Lyytikainen R, et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:575–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Littrell KH, Petty R, Ortega TR, et al. Insulin resistance and syndrome X among patients with schizophrenia. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, May 2003.

- 51.Ryan MCM, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:284–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subramaniam M, Chong SA, Pek E. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:345–7. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Almeras N, Deprés JP, Villeneuve J, et al. Development of an atherogenic metabolic risk profile associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:557–64. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohn T, Prud'homme D, Streiner D, et al. Characterizing coronary heart disease risk in chronic schizophrenia: high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:753–60. doi: 10.1177/070674370404901106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curkendall SM, Mo J, Glasser DB, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with schizophrenia in Saskatchewan, Canada. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:715–20. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kato MM, Currier MB, Gomez CM, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with schizophrenia. Prim Care Comp J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6:74–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hung CF, Wu CK, Lin PY. Diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mackin P, Watkinson H, Young AH. Prevalence of obesity, glucose homeostasis disorders and metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients taking typical or atypical antipsychotic drugs: a cross-sectional study. Diabetologia. 2005;48:215–21. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1641-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pandina G, Greenspan A, Bossie C, et al. The metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, New York City, May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saari KM, Lindeman SM, Viilo KM, et al. A 4-fold risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: the northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:559–63. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bermudes RA, Keck PE, Welge JA. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psychiatric inpatients with primary psychotic and mood disorders. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:491–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1133–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Correll CU, Frederickson AM, Kane JM, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of coronary heart disease in 367 patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:575–83. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagg S, Lindblom Y, Mjörndal T, et al. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among a Swedish cohort of patients with schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:93–8. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000188215.84784.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lamberti JS, Olson D, Crilly JF, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among patients receiving clozapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;7:1273–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu RR, Zhao JP, Liu ZN, et al. Effects of typical and atypical antipsychotics on glucose-insulin homeostasis and lipid metabolism in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:572–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Attux C, Quintana MI, Chavez AC. Weight gain, dyslipidemia and altered parameters for metabolic syndrome on first episode psychotic patients after six-month follow-up. Rev Bras Psiquiat. 2007;29:346–9. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462006005000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Birkenaes AB, Opjordsmoen S, Brunborg C, et al. The level of cardiovascular risk factors in bipolar disorder equals that of schizophrenia: a comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:917–23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics: results of the CLAMORS Study. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:162–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Hert M, Hanssens L, Wampers M, et al. Prevalence and incidence rates of metabolic abnormalities and diabetes in a prospective study of patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:560. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kurt E, Altinbas K, Alatas G, et al. Metabolic syndrome prevalence among schizophrenic patients treated in chronic inpatient clinics. Psychiatry in Turkey. 2007;9:141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 73.L'Italien GJ, Casey DE, Kan HJ. Comparison of metabolic syndrome incidence among schizophrenia patients treated with aripiprazole versus olanzapine or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1510–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mackin P, Bishop D, Watkinson A prospective study of monitoring practices for metabolic disease in antipsychotic-treated community psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mulder H, Franke B, van der Aart–van der Beek A, et al. The association between HTR2C gene polymorphisms and the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:338–43. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3180a76dc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saddichha S, Ameen S, Akhtar S. Incidence of new onset metabolic syndrome with atypical antipsychotics in first episode schizophrenia: a six-week prospective study in Indian female patients. Schizophr Res. 2007;95:247. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sanchez-Araña T, Touriño R, Hernandez JL, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among schizophrenic patients hospitalized in the Canary Islands. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2007;35:359–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Spelman LM, Walsh PI, Sharifi N, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Diabet Med. 2007;24:481–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Srisurapanont M, Likhitsathian S, Boonyanaruthee V, et al. Metabolic syndrome in Thai schizophrenic patients: a naturalistic one-year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;23:7–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suvisaari JM, Saarni SI, Perälä J, et al. Metabolic syndrome among persons with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in a general population survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1045–55. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teixeira PJR, Rocha FL. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome among psychiatric inpatients in Brazil. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;29:330–6. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462007000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tirupati S, Chua LE. Body mass index as a screening test for metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15:470–3. doi: 10.1080/10398560701636906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boke O, Aker S, Sarisoy G, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among inpatients with schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38:103–12. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.1.j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Correll CU, Frederickson AM, Kane JM. Equally increased risk for metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia treated with second generation antipsychotics. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:788–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cerit C, Özten E, Yildiz M. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and related factors in patients with schizophrenia. Turk J Psychiatry. 2008;19:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Hert M, Schreurs, Sweers K, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Hert M, Falissard B, Mauri M, et al. Epidemiological study for the evaluation of metabolic disorders in patients with schizophrenia: the METEOR study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(Suppl. 4):S444. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ellingrod VL, Miller DD, Taylor SF, et al. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in schizophrenia patients receiving antipsychotics genotyped for the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTH-FR) 677C/T and 1298A/C variants. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Graham KA, Cho H, Brownley KA, et al. Early treatment-related changes in diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk markers in first episode psychosis subjects. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hanssens L, van Winkel R, Wampers M, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of adiponectin plasma levels in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:308–14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1085–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rabe-Jabłońska J, Pawełczyk T. The metabolic syndrome and its components in participants of EUFEST. Psychiatr Pol. 2008;42:73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saddichha S, Manjunatha N, Ameen S, et al. Metabolic syndrome in first episode schizophrenia – a randomized double-blind controlled, short-term prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sengupta S, Parrilla-Escobar MA, Klink R, et al. Are metabolic indices different between drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients and healthy controls? Schizophr Res. 2008;102:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schorr SG, Lucas M, Slooff CJ, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic patients in the Netherlands. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(Suppl. 2):241. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suvisaari J, Perälä J, Saarni SI, et al. Type 2 diabetes among persons with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in a general population survey. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258:129–36. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0762-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Winkel R, van Os J, Celic, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis as an independent risk factor for metabolic disturbances: results from a comprehensive, naturalistic screening program. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1319–27. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bai YM, Chen TT, Yang WS, et al. Association of adiponectin and metabolic syndrome among patients taking atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia: a cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2009;11:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Basu R, Thimmaiah TG, Chawla JM, et al. Changes in metabolic syndrome parameters in patients with schizoaffective disorder who participated in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate. Asian J Psychiatry. 2009;2:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bodén R, Haenni A, Lindström L, et al. Biochemical risk factors for development of obesity in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:141–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bernardo M, Cañas F, Banegas JR, et al. Prevalence and awareness of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study in a low cardiovascular disease risk geographical area. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:431–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brunero S, Lamont S, Fairbrother G. Prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among patients attending an outpatient clozapine clinic in Australia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23:261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chien IC, Hsu JH, Lin CH, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan: a population-based National Health Insurance study. Schizophr Res. 2009;111:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gulzar M, Rafiq A, OCuill M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in elderly schizophrenic patients in Ireland. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(Suppl. 1):S85. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hatata H, El-Gohary G, Abd-Elsalam M, et al. Risk factors of metabolic syndrome among Egyptian patients with schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry. 2009;16:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Huang MC, Lu ML, Tsai CJ, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in Taiwan. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120:274–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin CC, Bai YM, Wang YC, et al. Improved body weight and metabolic outcomes in overweight or obese psychiatric patients switched to amisulpride from other atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:529–36. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181bf613e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Medved V, Kuzman MR, Jovanovic N, et al. Metabolic syndrome in female patients with schizophrenia treated with second generation antipsychotics: a 3-month follow-up. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:915–22. doi: 10.1177/0269881108093927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Meyer JM, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E. The moderating impact of ethnicity on metabolic outcomes during treatment with olanzapine and aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:318–25. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mulder H, Cohen D, Scheffer H, et al. HTR2C gene polymorphisms and the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: a replication study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:16–20. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181934462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oyekcin DG. The frequency of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Anatolian J Psychiatry. 2009;10:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Patel JK, Buckley PF, Woolson S, et al. Metabolic profiles of second-generation antipsychotics in early psychosis: findings from the CAFE study. Schizophr Res. 2009;111:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Perez-Iglesias R, Mata, Pelayo-Teran JM, et al. Glucose and lipid disturbances after 1 year of antipsychotic treatment in a drug-naïve population. Schizophr Res. 2009;107:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rezaei O, Khodaie-Ardakani MR, Mandegar MH. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among an Iranian cohort of inpatients with schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2009;39:451–62. doi: 10.2190/PM.39.4.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shi L, Ascher-Svanum H, Chiang YJ, et al. Predictors of metabolic monitoring among schizophrenia patients with a new episode of second-generation antipsychotic use in the Veterans Health Administration. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Steylen PMJ, van der Heijden FFMA, Verhoeven WMA, et al. Metabool syndroom bij de behandeling van clozapine. PW Wetenschappelijk Platform. 2009;3:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Verma SK, Subramaniam M, Liew A, et al. Metabolic risk factors in drug-naive patients with first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:997–1000. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bisconer SW, Harte BMB. Patterns and prevalence of metabolic syndrome among psychiatric inpatients receiving antipsychotic medications: implications for the practicing psychologist. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2010;41:244–52. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bresee LC, Majumdar SR, Patten SB, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease in people with schizophrenia: a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2010;117:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chiu CC, Chen CH, Chen BY, et al. The time-dependent change of insulin secretion in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:866–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Correll CU, Druss BG, Lombardo I, et al. Findings of a U.S. national cardiometabolic screening program among 10,084 psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:892–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.9.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fountoulakis KN, Siamouli M, Panagiotidis P, et al. Obesity and smoking in patients with schizophrenia and normal controls: a case-control study. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176:13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.De Hert M, Mittoux A, He Y, et al. Metabolic parameters in the short- and long-term treatment of schizophrenia with sertindole or risperidone. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261:231–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fan X, Liu EY, Freudenreich O. Higher white blood cell counts are associated with an increased risk for metabolic syndrome and more severe psychopathology in non-diabetic patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;118:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ferreira L, Belo A, Abreu-Lima C. A case-control study of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular risk among patients with schizophrenia in a country in the low cardiovascular risk region of Europe. Rev Port Cardiol. 2010;29:1481–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kim EY, Lee NY, Kim SH, et al. Change in the rate of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in the course of treatment. Presented at the 4th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Sao Paulo, March 2010.

- 127.Krane-Gartiser K, Breum L, Glümer C, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Danish psychiatric outpatients treated with antipsychotics. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2011;65:345–52. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.565799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kumar A, Tripathi A, Dalal P. Study of prevalence of metabolic syndrome in drug naive outdoor patients with schizophrenia and bipolar-I disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:132. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Larsen JT, Fagerquist M, Holdrup M, et al. Metabolic syndrome and psychiatrists' choice of follow-up interventions in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics in Denmark and Sweden. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2011;65:40–6. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2010.486443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lin CC, Bai YM, Chen JY, et al. Easy and low-cost identification of metabolic syndrome in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics: artificial neural network and logistic regression models. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:225–34. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04628yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Maslov B, Marcinko D, Milicevic R, et al. Metabolic syndrome, anxiety, depression and suicidal tendencies in post-traumatic stress disorder and schizophrenic patients. Coll Antropol. 2010;33:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Maayan LA, Vakhrusheva J. Risperidone associated weight, leptin, and anthropometric changes in children and adolescents with psychotic disorders in early treatment. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:133–8. doi: 10.1002/hup.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nielsen J, Skadhede S, Correll CU. Antipsychotics associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1997–2004. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Okumura Y, Ito H, Kobayashi M, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and antipsychotic prescription patterns in patients with schizophrenia: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2010;119:145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Padmavati R, McCreadie RG, Tirupati S. Low prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome in never-treated chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;121:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ramos-Ríos R, Arrojo-Romero M, Paz-Silva E. QTc interval in a sample of long-term schizophrenia inpatients. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Risselada AJ, Vehof J, Bruggeman R, et al. Association between HTR2C gene polymorphisms and the metabolic syndrome in patients using antipsychotics: a replication study. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;12:62–7. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Sato Y, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vuksan-Cusa B, Sagud M, Jakovljević M. C-reactive protein and metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder compared to patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:275–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Baptista T, Serrano A, Uzcátegui E, et al. The metabolic syndrome and its constituting variables in atypical antipsychotic-treated subjects: comparison with other drug treatments, drug-free psychiatric patients, first-degree relatives and the general population in Venezuela. Schizophr Res. 2011;126:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bresee LC, Majumdar SR, Patten SB, et al. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and health care use in people with and without schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Curtis J, Henry C, Watkins A, et al. Metabolic abnormalities in an early psychosis service: a retrospective, naturalistic cross-sectional study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5:108–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Grover S, Nebhinani N, Chakrabarti S, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in subjects receiving clozapine: a preliminary estimate. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:591–5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.84979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Güveli H, Cem Ilnem M, Yener F, et al. The frequency of metabolic syndrome in schizoprenia patients using antipsychotic medication and related factors. Yeni Symposium. 2011;49:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kang SH, Kim KH, Kang GY, et al. Cross-sectional prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korean patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;128:179–81. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Khatana SA, Kane J, Taveira TH, et al. Monitoring and prevalence rates of metabolic syndrome in military veterans with serious mental illness. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lee NY, Kim SH, Jung DC, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korean patients with schizophrenia receiving a monotherapy with aripiprazole, olanzapine or risperidone. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Mai Q, Holman CD, Sanfilippo FM, et al. Mental illness related disparities in diabetes prevalence, quality of care and outcomes: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2011;9:118. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nuevo R, Chatterji S, Fraguas D, et al. Increased risk of diabetes mellitus among persons with psychotic symptoms: results from the WHO World Health Survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1592–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Phutane VH, Tek C, Chwastiak L, et al. Cardiovascular risk in a first-episode psychosis sample: a 'critical period' for prevention? Schizophr Res. 2011;127:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Roshdy R. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2011;18:109–17. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Subashini R, Deepa M, Padmavati R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in subjects with and without schizophrenia (CURES-104) J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:272–7. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.90075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Van Der Heijden F, Steylen P, Kok H, et al. Low rates of treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in patients treated with antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(Suppl. 1):1522. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Vargas TS, Santos ZE. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic patients. Scientia Medica. 2011;21:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Yaziki MK, Anil Yağcioğlu AE, Ertuğrul A, et al. The prevalence and clinical correlates of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: findings from a cohort in Turkey. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Zhang R, Hao W, Pan M, et al. The prevalence and clinical-demographic correlates of diabetes mellitus in chronic schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26:392–6. doi: 10.1002/hup.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Benseñor IM, Brunoni AR, Pilan LA, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with first-episode psychosis in São Paulo, Brazil. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Beumer W, Drexhage RC, De Wit H, et al. Increased level of serum cytokines, chemokines and adipokines in patients with schizophrenia is associated with disease and metabolic syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1901–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Centorrino F, Masters GA, Talamo A, et al. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatrically hospitalized patients treated with antipsychotics and other psychotropics. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27:521–6. doi: 10.1002/hup.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Cheng C, Chiu HJ, Loh el W, et al. Association of the ADRA1A gene and the severity of metabolic abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;36:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Ellingrod VL, Taylor SF, Dalack G, et al. Risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in bipolar and schizophrenia subjects treated with antipsychotics: the role of folate pharmacogenetics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:261–5. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182485888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Fleischhacker WW, Siu CO, Bodén R, et al. Metabolic risk factors in first episode schizophrenia: baseline prevalence and course analyzed from the European first episode schizophrenia trial (EUFEST) Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:987–95. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Grover S, Nebhinani N, Chakrabarti S, et al. Metabolic syndrome in antipsychotic naïve patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6:326–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Kagal UA, Torgal SS, Patil NM, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic patients receiving second-generation antipsychotic agents – a cross-sectional study. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25:368–73. doi: 10.1177/0897190012442220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kirkpatrick B, Miller BJ, Garcia-Rizo CG, et al. Is abnormal glucose tolerance in antipsychotic-naïve patients with nonaffective psychosis confounded by poor health habits? Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:280–4. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Lancon C, Dassa D, Fernandez J, et al. Are cardiovascular risk factors associated with verbal learning and memory impairment in patients with schizophrenia? A cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;2012:204043. doi: 10.1155/2012/204043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Lee J, Nurjono M, Wong A, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2012;41:457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Lindenmayer JP, Khan A, Kaushik S, et al. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and cognition in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;142:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Martín Otaño L, Barbadillo Izquierdo L, Galdeano Mondragón A, et al. After six months of anti-psychotic treatment: is the improvement in mental health at the expense of physical health. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2013;6:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Miller BJ, Mellor A, Buckley P. Total and differential white blood cell counts, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and the metabolic syndrome in non-affective psychoses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Morden NE, Lai Z, Goodrich DE, et al. Eight-year trends of cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality in patients with schizophrenia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:368–79. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Na KS, Kim WH, Jung HY, et al. Relationship between inflammation and metabolic syndrome following treatment with paliperidone for schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Nurjono M, Lee J. Predictive utility of blood pressure, waist circumference and body mass index for metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia in Singapore. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;41:457–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Pallava A, Chadda R, Sood, et al. Metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: a comparative study of antipsychotic free/naïve and antipsychotic treated patients. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2012;66:215–21. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.621977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Said MA, Sulaiman AH, Habil MH, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics in Malaysia. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:801–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Subashini R, Deepa M, Padmavati R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in subjects with and without schizophrenia (CURES-104) J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:272–7. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.90075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Sweileh WM, Zyoud SE, Dalal SA, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia in Palestine. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:235. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Wampers M, Hanssens H, van Winkel R, et al. Differential effects of olanzapine and risperidone on plasma adiponectin levels over time: results from a 3-month prospective open-label study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Grover S, Nebhinani N, Chakrabarti S, et al. Comparative study of prevalence of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nordic J Psychiatry (in press) doi: 10.3109/08039488.2012.754052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Vancampfort D, Probst M, Scheewe T, et al. Relationships between physical fitness, physical activity, smoking and metabolic and mental health parameters in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Scheewe TW, Backx FJ, Takken T, et al. Exercise therapy improves mental and physical health in schizophrenia: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:464–73. doi: 10.1111/acps.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.De Hert M, Wampers M, Mitchell AJ, et al. Is schizophrenia an inflammatory multi-system disease? Submitted for publication.

- 183.Steiner J, Bernstein HG, Schiltz K, et al. Immune system and glucose metabolism interaction in schizophrenia: a chicken-egg dilemma. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (in press) doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.De Hert M, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, et al. Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:99–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Mitchell AJ, Delaffon, Vancampfort D, et al. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol Med. 2012;42:125–47. doi: 10.1017/S003329171100105X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, et al. Considering a frame of reference for physical activity research related to the cardiometabolic risk profile in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Vancampfort D, Knapen J, De Hert M, et al. Cardiometabolic effects of physical activity interventions for people with schizophrenia. Phys Ther Rev. 2009;14:388–98. [Google Scholar]

- 188.Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Skjaerven L, et al. International Organization of Physical Therapy in Mental Health consensus on physical activity within multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes for minimising cardio-metabolic risk in patients with schizophrenia. Disab Rehab. 2012;34:1–12. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.587090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, and recommendations at the system and individual levels. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:138–51. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Manu P, Correll CU, van Winkel R, et al. Prediabetes in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:460–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Manu P, Correll CU, Wampers M, et al. Prediabetic increase in hemoglobin A1c compared with impaired fasting glucose in patients receiving antipsychotic drugs. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Manu P, et al. How to use HbA1c and glucose tests to screen for diabetes in patients receiving antipsychotic medication: a large scale observational study. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 193.Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Yu W, et al. Can clinical features be used to screen for diabetes in patients with severe mental illness receiving antipsychotics? Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 194.Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Vansteenkiste M, et al. The importance of self-determined motivation towards physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 195.Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Vansteenkiste M, et al. Self-determination and stage of readiness to change physical activity behaviour in schizophrenia: a multicentre study. Submitted for publication.