Abstract

Background

This study's objective was to evaluate the role of psychological adjustment in the decision-making process to have an abortion and explore individual variables that might influence this decision.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we sequentially enrolled 150 women who made the decision to voluntarily terminate a pregnancy in Maternity Dr. Alfredo da Costa, in Lisbon, Portugal, between September 2008 and June 2009. The instruments were the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS), Satisfaction with Social Support Scale (SSSS), Emotional Assessment Scale (EAS), Decision Conflict Scale (DCS), and Beliefs and Values Questionnaire (BVQ). We analyzed the data using Student's T-tests, MANOVA, ANOVA, Tukey's post-hoc tests and CATPCA. Statistically significant effects were accepted for p<0.05.

Results

The participants found the decision difficult and emotionally demanding, although they also identified it as a low conflict decision. The prevailing emotions were sadness, fear and stress; but despite these feelings, the participants remained psychologically adjusted in the moment they decided to have an abortion. The resolution to terminate the pregnancy was essentially shared with supportive people and it was mostly motivated by socio-economic issues. The different beliefs and values found in this sample, and their possible associations are discussed.

Conclusion

Despite high levels of stress, the women were psychologically adjusted at the time of making the decision to terminate the pregnancy. However, opposing what has been previously reported, the women presented high levels of sadness and fear, showing that this decision was hard to make, triggering disruptive emotions.

Keywords: Abortion, Decision-making, Emotions, Psychological adjustment, Stress

Introduction

Most women resort to contraceptive methods to avoid unwanted pregnancies; however, accidental pregnancies still happen, whether it is due to failure of the chosen contraceptive method, or its incorrect use (1–3). Some authors interpret the absence of these methods, or incorrect use of them, as an unconscious desire for pregnancy (4, 5). However, most women who decide to terminate their pregnancy consider the conception as non-intentional, and associate it with negative emotional reactions (6). Nevertheless, this should be considered a situation of unwanted motherhood, as the project of having a child does not exist (7, 8).

Research attests that there are several underlying reasons to the decision to have an abortion, which are closely related to life circumstances and projects; thus the decision is a meaningful experience that reflects, and has an impact on personal characteristics (age, religion, attitudes regarding elective abortion, personality characteristics, previous experiences), motivations associated with relationships and social support (marital or parental status, family and social pressure), aspects related to economic and educational circumstances (professional and academic status), life contingencies, and the social, cultural and legal environment (9–15).

A study about the Portuguese position towards abortion (1), showed that the main motives to terminate a pregnancy were age (17.8%), economic status (14%), not wanting more children (13%), having had a child recently (10.4%), rejection of the pregnancy by the partner (9.4%), marital instability (9.1%), and family pressure (8%).

However, in Portugal, the study of demographic and motivational characteristics of women that seek abortion, the associated psychological aspects, and their reproductive experience, were limited due to legal contingencies that criminalized abortion for a long period of time. Thus, the few studies developed till now are small, limited, empirical or qualitative ones, which provide incomplete knowledge on this subject (1), and are most probably distorted by censorship (16, 17).

The voluntary termination of pregnancy was only legalized in Portugal on April 2007 (Law nr.16/2007, 17th of April). This law enabled women to have abortions in an official health establishment (e.g. hospital or clinic) until tenth week of pregnancy, and receive psychological support offered during the decision-making process (18).

Although many researchers consider that women do not face much difficulties in making the decision for an abortion, due to the low conflict levels in the decision, several studies have shown that it is hard and always involves ambivalence, and that women tend to experience significant levels of stress and, sometimes, clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety prior to abortion (1, 6, 19–22). The way women deal with this decision to terminate a pregnancy can be affected by several factors, including the ability to tolerate painful affections and ambivalence, perceived social support during the decision-making process, attitudes towards elective abortion, educational level, and past and present life circumstances, which can act as stress inducing situations (8, 23).

Given the fact that Portuguese public services offer, for the first time, the possibility to voluntarily terminate a pregnancy, we found it appropriate to undertake a study that aimed at assessing:

The psychological and relational adjustment at the decision-making moment through observing the psychopathological symptoms, emotional reactivity and perceived social support;

The perceived difficulty in the decision-making process: uncertainty in choosing among several options, the relevant contributing factors and quality of the decision;

Factors of inter-individual variability regarding the psychological adjustment to the decision.

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional study using a non-probabilistic sequential sample of 150 candidates who voluntarily sought to terminate pregnancies, in a public health service, in Lisbon, between September 2008 and June 2009. The research project was evaluated and approved by the institution's Ethics Committee.

The data collection was carried out in the Unwanted Pregnancy Consultation unit at maternity Dr. Alfredo da Costa, and it consisted of a single evaluation done during the pre-consultation period (first appointment before abortion). After explaining the study and guaranteeing the confidentiality and anonymity of the evaluation, the participants granted their informed consent.

Instruments

The instruments were socio demographic questionnaire, tailored for the study in order to characterize the study sample on a number of socio-demographic variables (including age, nationality, religion, ethnicity, educational level, professional situation, socio-economic level, and living conditions).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) (24), Portuguese adaptation (25) − this is a 21-item scale, divided in three subscales of depression, anxiety and stress, each with 7 items. The responses are given in a 4-point scale, where the respondent presents the level of agreement with the item (e.g. statements regarding negative emotional states felt during the past week). The score for each subscale is obtained by the sum of the items, with the minimum result of 0 and the maximum of 21 (the higher the score the more negative the affective state). The Portuguese modified version presented a good internal consistency (α ranged between 0.74 to 0.85), presenting similar psychometric characteristics for the Portuguese population as the original scale (25).

Satisfaction with Social Support Scale (SSSS) (26) − this 15-item scale measures four dimensions of social support: satisfaction with friends (5 items), intimacy (4 items), satisfaction with family (3 items), and social activities (3 items). The responses are given in a 5-point Likert scale, and results vary between 15 and 75 points. The Portuguese version presented a good internal consistency (α=0.85), (26).

Emotional Assessment Scale (EAS) (27), Portuguese adaptation (28) − it is a 24-item scale that evaluates the emotional reactivity of fundamental emotions: fear, happiness, anxiety, guilt, anger and surprise. The responses are given using a 10cm visual analogue scale, which ranges from “least possible” on the left to “most possible” on the right. The scoring of the intensity reported regarding each emotion word is obtained by measuring the distance (in millimeters) between the left endpoint to the slash mark made by the respondent. In the Portuguese study, the item's internal consistency was considered good (α values ranged between 0.7286 to 0.8818), (28).

Decision Conflict Scale (DCS) (29), Portuguese adaptation (30) – this is a 16-item scale that assesses the perceived difficulty in the decision-making process: uncertainty in choosing among several options, contributing factors and quality of the decision-making process. Responses are given on a 5-point Likert scale, which ranges from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”. The score is obtained by calculating the mean of the responses to each item. The higher the final score the greater the difficulty in making the decision. The Portuguese validation study presented an excellent internal consistency (Total α=0.9024) (30).

Beliefs and Values Questionnaire (BVQ) about sexuality, developed by the researchers and tailored for the Portuguese population (31) – this is a 38-item scale that evaluates the values and beliefs on sexuality in the dimensions of 1) Maternity (which assesses the perception of motherhood as a central project of being a woman); 2) Reproduction (which assesses the extent to which female sexuality is seen essentially in its procreative function); 3) Affectivity (assessing to which extent female sexuality is perceived as an affective area); 4) Abortion (which evaluates the negative representations of abortion); 5) Pleasure (which assesses the perception of female sexuality as a pleasure area). The responses are given using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “I totally disagree” to “I totally agree”. The final score is obtained through the calculation of the mean of the responses to the items. The validation study presented acceptable α values (0.560 to 0.782) (31).

Data Analysis

Student's t-tests were performed to compare two means, and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) followed by univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare more than two sets of means. When homoscedasticity requirement was not met in the ANOVA, we used Welch's corrected ANOVA. Tukey's post-hoc tests were used when ANOVA proved to be significant to identify the groups with statistically significant mean differences. Finally, to analyze the association pattern between the variables of the subscales, we used a Categorical Principal Component Analysis (CATPCA). Statistically significant effects were accepted for p<0.05.

Data analysis was conducted using the statistical software SPSS (Version 19, SPSS Inc., Chicago, ILL, USA).

Sample

The study sample was composed of 150 pregnant women, until tenth week of pregnancy, who made the decision to have an abortion.

Information on the participants’ clinical and abortion history is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and abortion history characterization of the participants

| Clinical and abortion history characteristics | (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of children | |

| 0 | 53.3 |

| 1 | 24 |

| 2 | 16.7 |

| 3 or more | 6 |

| Relationship context when pregnancy occurred | |

| Dating | 50.7 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 40.7 |

| Casual sexual intercourse | 8.7 |

| Contraception | |

| Pill | 37.3 |

| Condom | 29.3 |

| None | 30 |

| Gestation period | |

| 4-6 weeks | 46 |

| 7-9 weeks | 48.7 |

| 10 weeks | 5.3 |

| Shared the decision of having an abortion | |

| Partner | 72.7 |

| Friends | 36.4 |

| Mother/parents | 34.9 |

| Prior abortion history | |

| 0 prior abortions | 71.3 |

| 1 prior abortion | 21.3 |

| 2 or more prior abortions | 7.4 |

| Reasons for having an abortion | |

| Financial instability | 41.3 |

| Lack of (non-specified) residential conditions | 22.7 |

| Inconsistent marital relationship | 12 |

| Absence of the father | 6 |

| Child was not wanted | 5.3 |

| Being pressured to have an abortion | 1.3 |

| A combination of reasons | 20.7 |

Results

Demographic characteristics

The participants' age ranged from 13 to 44 years (M=26.03, SD=6.987), 76% were Portuguese and 20% from African countries; 73.3% were Caucasian and 26.7% were Black. Most participants had a secondary educational level (45.7%) and were professionally active (61.3%), the remaining 27.3% were students, and had a low socio-economic level (51.3%).

Analyzing psychological adjustment to the decision-making process, the means of all the three subscales including depression, anxiety and stress were low (Mdepression=5.9; Manxiety=5 and Mstress= 8.7), the values being below the considered “risk zone”, indicated that the women in our sample were psychologically adjusted to the condition.

As for Satisfaction with Social Support (SSSS), the means were high in all subscales, indicating a high perceived social support. Moreover, the means reached 75% of the maximum score in all subscales, except for the “social activities” subscale, i.e, the participants were less satisfied with their social activities than with any other social support dimension.

Concerning the Emotional Reactivity (EAS), we observed that the emotion with the highest mean was “sadness” (M=62.2), followed by “fear” (M= 61.7), “anxiety” (M=45.7), “surprise” (M=43.9), “anger” (M=41.5), “guilt” (M=35.1) and, finally, “happines” (M=18.0).

Moreover, the Conflict with the Decision (DCS) presented low mean score (M=1.56), indicating a low conflict in the decision-making. Analyzing some of the items individually, we observed that the first item ("this decision was easy to make") had the highest mean (M=3.20), i.e., despite an overall low conflict, women considered this a somewhat difficult decision, but not extremely difficult. However, in the second item ("I'm sure of the decision to make"), (M=1.53), the participants showed that, despite the difficulty, they were sure about their decision.

Concerning the values and beliefs about sexuality, pregnancy, maternity and abortion (BVQ) of the sample, which was originally used to assess BVQ, statistically significant differences with the general population for the subscales “motherhood” (p=0.017) “reproduction” ( p=0.026) and “affection” (p=0.047) were found. Since all the test statistics were positive (our sample vs. general population), we could infer that the women from our sample privileged sexuality as a source of affection, they had stronger beliefs related to the idea of motherhood as a central project in a woman's life, as well as regarding reproduction as a primary function of female sexuality, and had a more positive view of abortion.

Factors of inter-individual variability in the psychological adjustment to the decision of terminating the pregnancy

We also analyzed individual and relational variables considered relevant in the literature. Of these, we presented only the findings that had statistically significant effects (p<0.05).

Age group was one of the most important socio-demographic variables to explain the beliefs and values regarding sexuality (Pillai's trace=0.315; F(20,576)=2.458; p<0.001; η2 p=0.079; π=0.998). The subsequent ANOVA revealed statistically significant effects of age on the dimensions “reproduction” (F(4,145)=3.916; p=0.005; η2 p=0.098; π=0.72) and “Pleasure” (F(4,145)=2.598; p= 0.039; η2 p=0.067; π=0.72).

Regarding the age groups, teenagers (13 to 18 years old), had the strongest beliefs of reproduction as the primary function of female sexuality (13 to 18 and 19 to 24, p=0.04; 13 to 18 and 25 to 29, p=0.003; 13 to 18 and 30 to 35, p=0.021), (Table 2).

Table 2.

Values and beliefs related to age (ANOVA)

| BVQ | [13;18] | [19;24] | [25;29] | [30;35] | [36;44] | ANOVA | |

| (n=23) | (n=44) | (n=41) | (n=25) | (n=17) | F | P | |

| Reproduction | 2.64±0.666* | 2.12±0.686* | 1.97±0.632* | 2.01±0.557* | 2.31±1.077* | 3.916 | 0.005 |

Mean±SD

The relational context was influenced by beliefs and values (Pillai's trace=0.120; F(10,288)=1.833; p=0.05; η2 p=0.06; π=0.842). Subsequent analysis revealed significant effects over the dimensions “Maternity” (F(2,147)=3.442; p=0.035; η2 p=0.045; π=0.638) and “Pleasure” (F(2,147)=3.576; p=0.03 η2 p=0.046; π=0.656). Moreover, women who were married or cohabiting tended to assess motherhood as the central project of womanhood, and female sexuality as an area of pleasure (p=0.030), in opposition to women who were dating or had casual relations (p=0.024).

Furthermore, stress and anxiety levels were marginally affected by the socio-economic level (Pillai's trace=0.107; F(9,438)=1.796; p=0.06; η2 p=0.036; π=0.806). A post-hoc analysis was performed and showed significantly higher levels of anxiety (p=0.005) and stress (p=0.035) in women with lower socio-economic levels when compared to those with higher levels. The socio-economic level also influenced the perceived social support dimensions (Pillai's trace=0.145; F (12,435)=1.836; p=0.04; η2 p=0.048; π=0.895). Also, we found that women with lower socio-economic levels were more unsatisfied regarding the intimate social support (p=0.034), and had stronger beliefs regarding motherhood (p=0.003) and procreation1 (p=0.027) as the women's main functions.

Moreover, the level of overall satisfaction (with social support and social activities) was higher among participants with a higher social status, and the dimension of sexual pleasure was more valued by these women (p=0.037), (Table 3).

Table 3.

Psychopathological symptoms, social support, values and beliefs in different socio-economic levels

| Low (n=77) |

Medium (n=23) |

High (n=9) |

Student (n=41) |

ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | P | |

| DASS | ||||||||||

| Depression | 7.10 | 5.760 | 4.26 | 4.760 | 3.33 | 3.082 | 5.15 | 4.084 | 3.973 (W) | 0.016 |

| Anxiety | 6.13 | 5.051 | 2.52 | 3.800 | 2.67 | 2.345 | 4.78 | 3.857 | 6.422 (W) | 0.001 |

| Stress | 9.92 | 5.951 | 6.48 | 5.026 | 5.89 | 1.900 | 8.15 | 4.580 | 6.687 (W) | 0.001 |

| SSSS | ||||||||||

| Intimacy | 14.29 | 4.029 | 17.09 | 3.502 | 17.78 | 2.539 | 15.76 | 2.981 | 6.116 (W) | 0.002 |

| Social Activities | 9.16 | 3.337 | 11.74 | 3.427 | 10.00 | 3.606 | 10.51 | 3.257 | 3.787 (W) | 0.020 |

| Total | 53.42 | 13.13 | 62.65 | 13.55 | 60.89 | 10.65 | 58.56 | 9.935 | 3.824 (W) | 0.019 |

| BVQ | ||||||||||

| Maternity | 3.46 | 0.893 | 2.75 | 0.866 | 3.00 | 0.566 | 2.87 | 0.792 | 6.759 | <0.001 |

| Procreation | 2.25 | 0.791 | 1.77 | 0.598 | 2.11 | 0.471 | 2.23 | 0.673 | 3.564 (W) | 0.024 |

| Pleasure | 3.87 | 0.615 | 3.75 | 0.780 | 4.26 | 0.572 | 3.60 | 0.684 | 3.223 (W) | 0.036 |

(W): ANOVA with Welch's correction

Also participants with a lower education level felt more anxious, had less satisfaction in perceived social support and the level of intimacy , valued the project of motherhood more, and viewed sexuality as an area of affection (p<0.05).

On the other hand, participants with higher educational levels tended to privilege pleasure in their sexual experience (Table 4). Moreover, contraception use had significant effects on women's beliefs and values towards sexuality. Women who did not use contraception had stronger beliefs about reproduction as the primary objective of sexual intercourse, than women who used contraception (F (1,148)=3.635; p=0.009; η2 p=0.046; π= 0.752).

Table 4.

Psychopathological symptoms, social support, values and beliefs in different education levels

| Primary education (n=61) |

Secondary education (n=68) |

Higher education (n=21) |

ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | P | |

| DASS | ||||||||

| Anxiety | 6.00 | 4.676 | 4.71 | 4.676 | 3.05 | 2.801 | 5.920 (W) | 0.004 |

| SSSS | ||||||||

| Intimacy | 14.54 | 3.640 | 15.49 | 3.881 | 17.10 | 3.300 | 4.432 (W) | 0.016 |

| BVQ | ||||||||

| Maternity | 3.45 | 0.830 | 2.99 | 0.927 | 2.89 | 0.776 | 5.516 | 0.005 |

| Procreation | 2.35 | 0.794 | 2.06 | 0.706 | 1.94 | 0.479 | 4.260 (W) | 0.018 |

| Affectivity | 4.33 | 0.676 | 4.12 | 0.707 | 3.78 | 0.791 | 4.374 (W) | 0.017 |

| Pleasure | 3.85 | 0.634 | 3.67 | 0.711 | 4.07 | 0.567 | 3.302 | 0.040 |

(W): ANOVA with Welch's correction

Levels of stress, anxiety and depression differed significantly among women with different gestation periods (Pillai's trace=0.052; F(3,146)= 2.657; p=0.05; η2 p=0.042; π=0.711). A post-hoc analysis revealed that women with shorter gestation periods exhibited lower levels of depression (p=0.01), anxiety (p=0.012) and stress (p=0.034), less conflict in the decision-making (p=0.003), and less firm beliefs about sexuality as a way to find affection (p=0.023).

The number of previous pregnancies was also influential on women's beliefs and values regarding sexuality (Pillai's trace=0.325; F(30,725)= 1.656; p=0.016; η2 p=0.065; π=0.993). Thus, primiparous women that were more fearful (p= 0.014) had stronger beliefs about the importance of motherhood in a woman's life (p<0.001), about pleasure in female sexuality (p=0.007), and had more negative feelings regarding abortion (p=.043), when compared with women with two or more previous pregnancies. Likewise, nulliparous women were also fearful (p=0.038), but they had weaker beliefs regarding motherhood as the central project of womanhood (p=0.001), and about the experience of sexuality as a source of pleasure (p=0.004).

No statistically significant differences were found regarding religion, ethnicity, or previous abortions at the level of psychopathological symptoms, satisfaction with social support, emotional reactivity, or conflict in the decision-making, values or beliefs.

Characterization of psychological adjustment to the decision of pregnancy termination

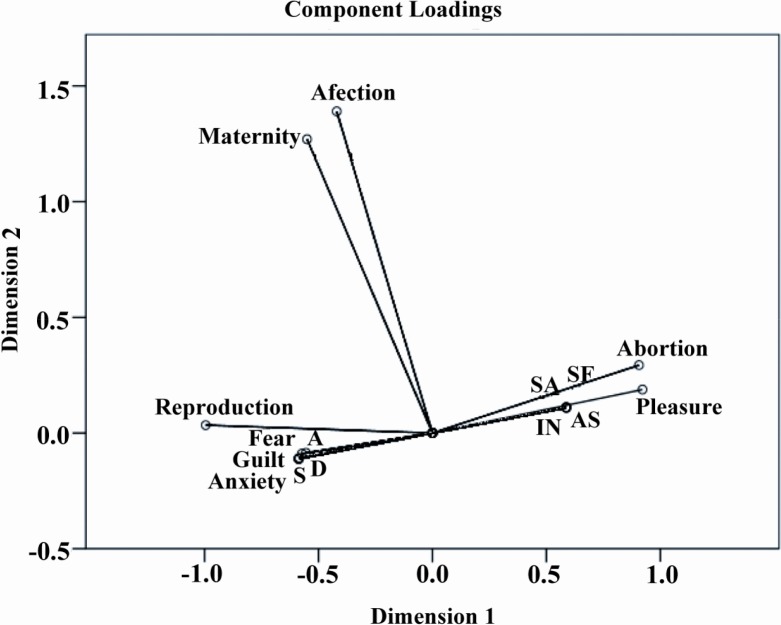

To better understand and characterize the psychological adjustment of the participants, when faced with the decision to have an abortion, we used a Principal Component Analysis with the objective of analyzing the association between several subscales (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Categorical principal component analysis

The results showed that the variables depression, anxiety, stress, fear, happiness, guilt, anger, surprise, sadness, conflict in the decision-making and reproduction were opposite to satisfaction with friends, intimacy, satisfaction with family, social activities, abortion and pleasure. Thus, women with higher scores in satisfaction with social support had lower psychopathological symptoms, lower emotional reactivity and lower conflict with the decision-making.

Regarding values and beliefs, we noticed that the highest scores of the variables abortion and pleasure, were opposite to those of reproduction, i.e. women with a higher representation of sexuality as a pleasurable action and a poorer representation of abortion, had weaker beliefs about the procreation as the major function of female sexuality.

On the other hand, the variables motherhood and affectivity were orthogonal to the remaining variables, i.e. the perception of motherhood as a determinant project of the female status, as well as the perception of sexuality as an area of affection, did not relate to the remaining variables.

Discussion

The results obtained in this study can be divided in to those that were congruent with the literature, and those that were contradictory.

Congruently with what is found in the literature, we observed that the decision to have an abortion is mostly shared with supportive people (partner, friends, parents), and revealed to be essentially shaped by socio-economic motivations (1, 10, 11, 13). Despite considering this decision difficult and emotionally demanding, the participants identified a low conflict in making it. This range of positive and negative feelings, can coexist or alternate in the same woman (6, 15), which is part of the crisis reaction experienced by an unwanted pregnancy and the process of making the decision to terminate it (20).

Furthermore, the women's values and beliefs concerning sexuality, motherhood and abortion, emphasized sexuality as a source of affection rather than pleasure, motherhood as the central project of women's lives, and they also presented more positive feelings about abortion than the general population. Congruent with the literature review, the psychological adjustment, observed in the decision-making moment, was associated to individual and relational variables, namely with the educational level, the socio-economic status and the obstetric history.

Regarding the association between subscales, stronger beliefs about reproduction as a primary function in female sexuality, seem to be associated to a higher level of conflict in the decision-making process and, consequently, a higher emotional reactivity regarding this decision, thus, exhibiting a more intense manifestation of psychopathological symptoms.

Moreover, the valorization of pleasure dimension in female sexuality seems to be related to a greater satisfaction with social support, which can be due to a less traditionally-oriented image of women, female sexuality and the roles associated with each gender. Women with stronger beliefs in this dimension were also the ones with the highest level of education.

However, some of our results were not entirely in agreement with those of previous studies.

Concerning psychological adjustment at the time of the decision-making process, the participants were psychologically adjusted despite showing high levels of stress. These results, although consistent with some studies, distance themselves from the dominant position in the literature (15, 22, 32).

Moreover, by exhibiting higher levels of sadness and fear, and lower levels of guilt and happiness, these women showed that the decision of terminating a pregnancy was hard to make, and triggered disruptive affection, which, although consistent with some literature (1, 20, 32), contradicted the idea of most women taking abortion “lightly”.

Finally, we found that the negative representations of abortion were negatively associated with reproduction, emotional reactivity and conflict in the decision-making. We believe that this finding needs to be further explored in future research, given that the negative representations of abortion are presented in a subscale related to the physical and psychological consequences of abortion. As the Portuguese law, regarding the legalization of abortion, only recently changed, these results may be either due to the respondents’ current representations, or a result of the maintenance of old representations (e.g. 33). This finding, which seems the most important one in this research, has the aforesaid limitation, apart from the fact that we had a sample of only 150 women.

Additionally, we observed a positive attitude towards motherhood and towards seeking affection and sharing through sexual relationships, regardless of whether these women identified themselves with the idea of sexuality for pleasure or for reproduction.

Conclusion

Despite high levels of stress, the women in our sample were psychologically adjusted at the time of making the decision to terminate the pregnancy. However, opposing what has been previously reported in the literature, the women presented high levels of sadness and fear, showing that this decision was hard to make, triggering disruptive emotions.

To cite this article: Sereno S, Leal I, Maroco J. The Role of Psychological Adjustment in the Decision-making Process for Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy. J Reprod Infertil. 2013;14(3):143-151.

Footnotes

Reproduction

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Associação para o Planeamento da Família. [The situation of abortion in Portugal: Practices, contexts and problems]; Lisboa: Associação para o Planeamento; 2007. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barden-O'Fallon JL, Speizer IS, White JS. Association between contraceptive discontinuation and pregnancy intentions in Guatemala. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2008;23(6):410–7. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892008000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Read C, Bateson D, Weisberg E, Estoesta J. Contraception and pregnancy then and now: examining the experiences of a cohort of mid-age Australian women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(4):429–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leal I. [Psychology of Pregnancy and Parenthood]; Lisboa: Fim de Século; 2005. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tachibana M, Santos LP, Duarte CAM. [The conflict between the conscious and unconscious in un-planned pregnancy] Psychê. 2006;10(19):149–67. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kero A, Högberg U, Jacobsson L, Lalos A. Legal abortion: a painful necessity. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(11):1481–90. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leal I. [Opening note] Análise Psicológica. 1998;3(16):363–4. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roynet D. [Making waves: adolescence and sex] Sexualidade & Planeamento Familiar. 2008;50/51:29–33. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berer M. Making abortion a woman's right world-wide. Making abortion a woman's right worldwide. Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10(19):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(02)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broen AN, Moum T, Bödtker AS, Ekeberg O. Rea-sons for induced abortion and their relation to women's emotional distress: a prospective, two-year follow-up study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Timing of steps and reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States. Contraception. 2006;74(4):334–44. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkman M, Rowe H, Hardiman A, Mallett S, Rosenthal D. Reasons women give for abortion: a review of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(6):365–78. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santelli JS, Speizer IS, Avery A, Kendall C. An exploration of the dimensions of pregnancy intentions among women choosing to terminate pregnancy or to initiate prenatal care in New Orleans, Louisiana. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(11):2009–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sihvo S, Bajos N, Ducot B, Kaminski M. Women's life cycle and abortion decision in unintended pregnancies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(8):601–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.8.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stotland NL. Induced abortion in the United States. In: Scotland NL, Stewart DE, editors. Psychological aspects of women and health care: The interface between psychiatry and obstetrics and gynecology. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. pp. 219–39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Statistics, Department of Health. Abortion Statistics, England and Wales: 2006. Statistical Bulletin [Internet]. 2007 Jun [cited 2012 Dec]; Available from: http://www.mariestopes.org.uk/documents/UK%20Abortion%20Statistics%202006.pdf.

- 17.Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Ahman E, Shah IH. Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends world-wide. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1338–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beja V, Leal I. Abortion counselling according to healthcare providers: a qualitative study in the Lisbon metropolitan area, Portugal. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2010;15(5):326–35. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2010.513213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler NE, David HP, Major BN, Roth SH, Russo NF, Wyatt GE. Psychological factors in abortion. A review. Am Psychol. 1992;47(10):1194–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.10.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradshaw Z, Slade P. The effects of induced abortion on emotional experiences and relationships: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23(7):929–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman PK. Resolution of unwanted pregnancy during adolescence through abortion versus child-birth: Individual and family predictors and psychological consequences. J Youth Adolescence. 2006;35:903–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauzon P, Roger-Achim D, Achim A, Boyer R. Emotional distress among couples involved in first-trimester induced abortions. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2033–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broen AN, Moum T, Bödtker AS, Ekeberg O. Predictors of anxiety and depression following pregnancy termination: a longitudinal five-year follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(3):317–23. doi: 10.1080/00016340500438116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pais-Ribeiro J, Honrado A, Leal I. [Contribution to the study of the Portuguese adaptation of the scale of depression and anxiety by Lovibond and Lovi-bond] Psycologica. 2004;36:235–46. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pais-Ribeiro J. [Satisfaction with Social Support Scale (SSSS)] Análise Psicológica. 1999;17(3):547–58. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson CR, Collins FL, Stewart JF, Porzellius J, Nitz JA, Lind CO. The assessment of emotional reactivity: A scale development and validation study. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1989;11(4):313–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moura-Ramos MC. Adaptação materna e paterna ao nascimento de um filho: Percursos e contextos da infância; Universidade de Coimbra; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocha JC. Factores Psicológicos da Mulher Face à Interrupção Médica da Gravidez; Universidade do Porto; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sereno S, Leal I, Maroco J. [Development and validation of a questionnaire of values and beliefs about sexuality, motherhood and abortion] Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças. 2009;10(2):193–204. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizzardo R, Magni G, Desideri A, Consentino M, Salmaso P. Personality and psychological distress before and after legal abortion: a prospective study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;13(2):75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chelstowska A. Stigmatisation and commercialisation of abortion services in Poland: turning sin into gold. Reprod Health Matters. 2011;19(37):98–106. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]