Significance

The transcription factor NF-κB is crucially involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and represents a target for treatment. However, a general blockade of NF-κB by small-molecule inhibitors is associated with serious side effects due to the importance of NF-κB in cellular survival and function of various organs. This paper demonstrates that cell type-specific NF-κB inhibition can be achieved using multi-modular fusion proteins, which exclusively target activated endothelial cells. Inhibition of NF-κB within activated endothelium potently ameliorated peritonitis and arthritis in mice, indicating that endothelial NF-κB might be a valid target in inflammatory diseases. Importantly, this strategy enables the targeting of other cell types and intracellular signaling pathways.

Keywords: cell targeting, intracellular signaling, autoimmune disorders, mouse models, inhibit inflammation

Abstract

Activation of the nuclear transcription factor κB (NF-κB) regulates the expression of inflammatory genes crucially involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. NF-κB governs the expression of adhesion molecules that play a pivotal role in leukocyte–endothelium interactions. We uncovered the crucial role of NF-κB activation within endothelial cells in models of immune-mediated diseases using a “sneaking ligand construct” (SLC) selectively inhibiting NF-κB in the activated endothelium. The recombinant SLC1 consists of three modules: (i) an E-selectin targeting domain, (ii) a Pseudomonas exotoxin A translocation domain, and (iii) a NF-κB Essential Modifier-binding effector domain interfering with NF-κB activation. The E-selectin–specific SLC1 inhibited NF-κB by interfering with endothelial IκB kinase 2 activity in vitro and in vivo. In murine experimental peritonitis, the application of SLC1 drastically reduced the extravasation of inflammatory cells. Furthermore, SLC1 treatment significantly ameliorated the disease course in murine models of rheumatoid arthritis. Our data establish that endothelial NF-κB activation is critically involved in the pathogenesis of arthritis and can be selectively inhibited in a cell type- and activation stage-dependent manner by the SLC approach. Moreover, our strategy is applicable to delineating other pathogenic signaling pathways in a cell type-specific manner and enables selective targeting of distinct cell populations to improve effectiveness and risk–benefit ratios of therapeutic interventions.

A critical step in the effector phase of pathogenic immune responses is the extravasation of circulating leukocytes from the vasculature and their migration along gradients of chemoattractants into the target tissues (1). In inflammation, endothelial activation represents a multistep cascade of events leading to increased vascular permeability for plasma proteins; the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and enzymes; and an up-regulation of adhesion molecules that are regulated by the nuclear transcription factor κB (NF-κB) (2–4).

Activation of NF-κB via the IκB kinase (IKK) complex is regarded as the classical NF-κB pathway. The IKK complex contains the kinases IKK1 and IKK2 and the regulatory subunit NF-κB Essential Modifier (NEMO) (5). Activation of the classical NF-κB pathway requires association of NEMO with IKK2 (5). The expression of multiple proinflammatory genes including the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin, and chemokines, like MCP-1 and IL-8, contributes to the inflammatory endothelial cell response and is initiated through activation of the classical NF-κB pathway (6).

Deregulated NF-κB has been implicated in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (7–9). In animal models, arthritis could be ameliorated by general NF-κB inhibition (10, 11). However, NF-κB activation is also involved in the resolution of inflammation and hence may exert positive or negative effects on inflammatory processes depending on the cell type and the disease phase (12).

Thus far, attempts to interfere with endothelial cell function as a therapeutic strategy in arthritis have remained rather limited and focused on the inhibition of synovial neoangiogenesis (13) or on attempts to directly block leukocyte extravasation by monoclonal antibodies targeting selectins and/or endothelial integrins in different experimental arthritis models (3, 10, 14–17) and patients (18). However, it is still poorly understood whether the extent of tissue damage in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases like RA is directly dependent on enhanced leukocyte recruitment in response to NF-κB activation and whether the endothelium is the critical compartment of NF-κB activity. Filling this gap in our knowledge not only will improve our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms but also may help to develop targeted therapeutic strategies. Moreover, NF-κΒ activation in the vascular endothelium is crucially involved in the development of atherosclerosis. The transgenic expression of an IκΒα mutant in endothelial cells protected Apo E−/− mice (Tie2DNIkBa/ApoE−/− mice) from atherosclerosis (19), and myeloid-specific IKKβ deletion decreased atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice (20). Repetitive systemic inflammatory responses are characteristic features of autoimmune diseases like RA that compose a cytokine-mediated activation of the endothelium. Accordingly, evaluation of the pathogenicity of endothelial NF-κΒ might identify treatment options for inflammatory tissue damage as well as its accompanying systemic comorbid conditions (21).

In this study, we investigated the role of NF-κB in the activated endothelium in murine models of peritonitis and RA. We developed an E-selectin–specific NF-κB inhibitor to selectively target activated endothelial cells. This fusion protein, designated as “sneaking-ligand construct” (SLC) 1, consists of a ligand-binding motif for high avidity interaction with E-selectin and endocytosis (22), a translocation domain to ensure endosomal release (23) and a NEMO-binding peptide (NBP) disrupting the IKK complex (24). This approach to cell type-specific and activation status-dependent targeting of NF-κB revealed that the extravasation of inflammatory cells in peritonitis as well as synovial leukocyte infiltration in arthritis is critically dependent on endothelial NF-κB activation via the classical pathway. Thus, we provide a proof of concept for the therapeutic application of an endothelial cell-specific NF-κB blockade in immune-mediated diseases.

Results

Generation of Sneaking Ligands Inhibiting NF-κB in the Activated Endothelium.

Transgenic and knockout mice have been used to clarify the role of molecules and signaling pathways in endothelial cells for the pathogenesis of diseases (19, 25). However, this approach is time-consuming and costly and does not allow the investigation of the effects of short-term modulation unless complex inducible systems are used. To gain insight into the function of NF-κB in activated endothelium, we took advantage of cytokine-induced E-selectin expression (2–4) and engineered the modular NF-κB inhibitor SLC1 for bacterial expression (26). The prototypic SLC1 is composed of three modules: (i) the targeting domain, consisting of three repeats of an E-selectin–binding peptide (AF10166 DITWDQLWDLMK) termed EBL (22) that confers high avidity to E-selectin and leads to receptor-mediated endocytosis, (ii) the translocation domain of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (ETAII) (23) to facilitate endosomal release of the effector domain into the cytosol, and (iii) the NBP encompassing amino acids 644–756 of IKK2 to serve as the effector domain for inhibition of the classical NF-κB pathway (24, 27). The integrated KDEL retention signal supports the transport of SLCs to the ER in a retrograde manner and the subsequent release into the cytsol (28). In Fig. 1, the composition of SLC1 is illustrated and its amino acid sequence is shown in Fig. S1A. Fig. 1 also depicts additional fusion proteins generated to control for the functional contributions of the EBL domain [mutated to a nonfunctional variant (MutEBL) or deletion variant (DelEBL)], the NBP domain [mutated to nonfunctional variants in MutNBP1 and MutNBP2], and the ETAII domain [DelETA, deletion of ETAII domain]. SDS/PAGE (Fig. S1B) and Western blot (Fig. S1C) analyses demonstrated high purities of the recombinant proteins. Using an antibody against the N-terminal Strep-Tag, we identified SLC1 as well as MutEBL, MutNBP1, and MutNBP2 migrating at the expected molecular weight of 39 kDa. The control construct DelEBL has a size of 32 kDa (Fig. S1C). An IKK2-specific antibody was applied for the detection of the C-terminal NBP domain to prove the expression of full-length proteins (Fig. S1D).

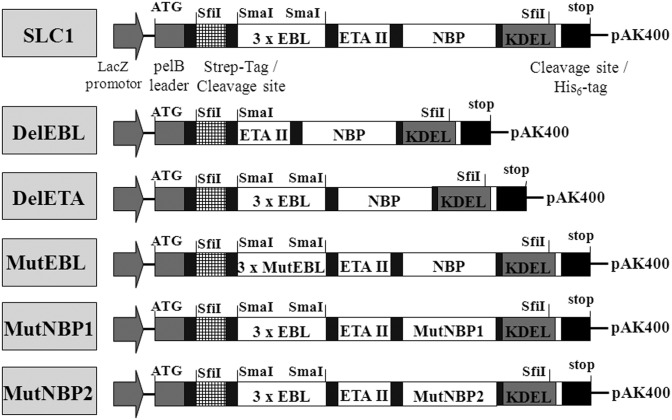

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of functional and nonfunctional SLCs. The multimodular synthetic gene was ligated into the pAK400 plasmid using SfiI restriction sites. EBL, three repeats of E-selectin–specific peptide (DITWDQLWDLMK) connected with a S4G linker. MutEBL, WKLDTLDMIQD (22). ETA II, translocation domain of Pseudomonas exotoxin A domain II (23). NBP, NEMO-binding peptide encompassing amino acids 644–756 from IKK2 (24). Amino acids that were identified for NEMO interaction were mutated: MutNBP1 FTALDASALQTE. MutNBP2 (scrambled peptide): DLAWQTFLTES.

First, we tested the binding capacity of our fusion protein by cell-based ELISA. SLC1 and MutNBP2 bound specifically to cells transfected with mouse E-selectin (CHO_E), whereas MutEBL and DelEBL did not, indicating the importance of the functional EBL domain for E-selectin binding (Fig. S1E). Furthermore, SLC1 did not interact with ICAM-1–transfected CHO cells (CHO_I) or wild-type CHO cells (CHO_wt), confirming its specificity for E-selectin (Fig. S1F).

NF-κB Inhibition via E-Selectin–Mediated Endocytosis of SLC1 in Vitro.

The translocation of surface-bound SLC1 into the cytoplasm is a prerequisite for inhibition of NF-κB activation. For these studies, the infrared-fluorescent protein FP635 (mKATE) was cloned into the sneaking ligand constructs for their visualization (29, 30). We examined the uptake of SLC1-FP635 into CHO_E cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. A temperature-sensitive receptor-mediated endocytotic uptake was indicated by the intracellular distribution of SLC1-FP635 upon incubation at 37 °C for 90 min (Fig. 2A), whereas parallel experiments performed at 4 °C resulted in a SLC1-FP635 staining pattern that colocalized with the fluorescence signal of the AlexaFluor488-labeled ConA plasma membrane marker (Fig. 2B).

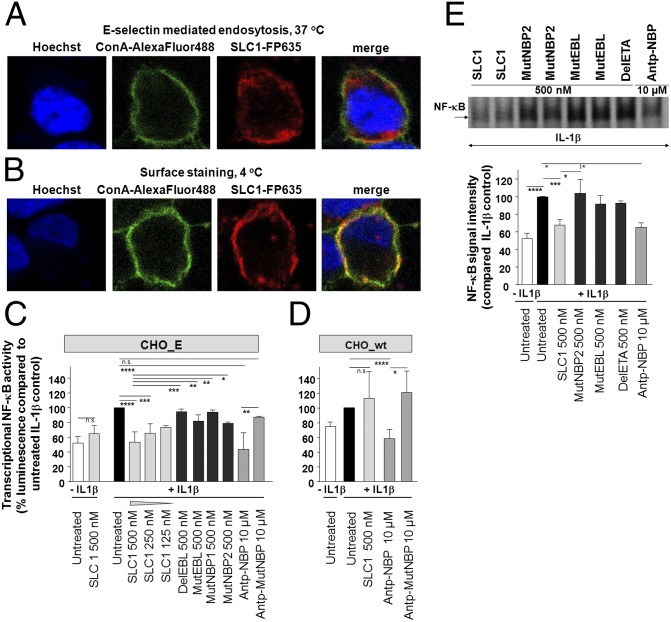

Fig. 2.

Internalized SLC1 selectively inhibits NF-κB activation in vitro. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy depicts CHO_E cells stained with SLC1-FP635 at 37 °C. Plasma membrane was stained with AlexaFluor488-labeled ConA. (B) CHO_E cells were stained with SLC1-FP635 at 4 °C. Experiments were performed at least five times. (C) NF-κB–dependent luciferase expression is reduced in SLC1-pretreated CHO_E cells in a dose-dependent manner. Error bars represent the ±SD obtained from five independent experiments. Each experiment was done in triplicate. (D) Transcriptional NF-κB activity is not reduced by SLC1 in CHO_wt cells. (E) NF-κB EMSA in SLC1-pretreated and IL-1β–stimulated CHO_E cells demonstrates inhibition of NF-κB nuclear DNA-binding activity. Representative independent experiments are shown. Experiments were performed five times. Densitometric analysis shows inhibition of NF-κB DNA-binding activity by ∼35% upon SLC1 treatment. Densitometric measurements were performed from five separate experiments. P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison post test: ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

We have previously established that an antennapedia-linked cell-permeable NBP (Antp-NBP) blocks the association of NEMO with IKK2 and inhibits activation of the classical NF-κB pathway (24). To analyze the effects of SLC1 treatment on cytokine-induced NF-κB activity, we performed NF-κB–dependent luciferase reporter gene assays in the CHO cell lines and compared the effects of SLC1 with Antp-NBP. CHO_E or CHO_wt cells were pretreated for 90 min at 37 °C with a range of concentrations of SLC1 (125–500 nM), then NF-κB was activated by IL-1β. Transcriptional NF-κB activity was significantly reduced in SLC1-treated CHO_E cells (Fig. 2C), but not in CHO_wt cells (Fig. 2D). In contrast, Antp-NBP reduced the transcriptional NF-κB activity in both CHO_E and CHO wt cells, whereas the mutated Antp-NBP (Antp-MutNBP) did not affect NF-κB activity (Fig. 2 C and D). Consistent with the previous finding that cell-permeable NBP treatment does not block basal NF-κB activity (24), SLC1 did not decrease NF-κB activity in resting cells but prevented the cytokine-mediated NF-κB induction (Fig. 2C). We did not detect significant effects on the transcriptional NF-κB activity in cells treated with the controls MutEBL, DelEBL, MutNBP1, and MutNBP2.

We next measured the NF-κB DNA-binding activity of nuclear extracts from SLC1-treated cells using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). Incubation of CHO_E cells with SLC1 before incubation with IL-1β resulted in a reduced NF-κB DNA-binding activity, indicating that SLC1 inhibits the IKK complex activity and, thereby, prevents the translocation of NF-κB proteins into the nucleus (Fig. 2E). In contrast, MutNBP2, MutEBL, and DelETA treatment did not affect NF-κB activation (Fig. 2E). Moreover, SLC1 treatment (500 nM) decreased DNA-binding activity to a similar level as Antp-NBP (10 µM). Quantitative densitometry of independent EMSA experiments revealed a significant reduction in NF-κB DNA-binding activity in SLC1-treated CHO_E cells (67.5% compared with IL-1β control) (Fig. 2E). EMSA supershift analyses showed that the NF-κB complexes in IL-1β–activated cells consisted almost exclusively of p50/p65 complexes, indicating activation of the classical NF-κB pathway. In SLC1-treated activated cells, the NF-κB DNA-binding activity was markedly reduced, but still virtually all complexes were shifted with antibodies to p50 and p65 (Fig. S2A). Furthermore, SLC1 did not affect p38 or AP-1 activation (c-Jun, JunB) in cytokine-activated CHO_E cells (Fig. S2B). Collectively, these data establish that the EBL and NBP domains of SLC1, as well as the ETAII domain, are essential for NF-κB inhibition and that SLC1 selectively targets the classical NF-κB pathway.

Endothelial NF-κB Blockade with SLC1 Prevents Leukocyte Trafficking.

The interaction of leukocytes with endothelium is mediated by NF-κB–dependent adhesion molecules expressed on activated endothelial cells. We therefore questioned whether interference with the IKK complex assembly significantly influenced leukocyte binding to and migration across cytokine-activated endothelium. IL-1β−stimulated mouse endothelial cells (mlEND) were incubated for 4 h with SLC1 before adding granulocytes. Pretreatment of endothelial cells with SLC1 but not with the dysfunctional controls MutNBP2, MutEBL, and DelEBL caused a reduction in the percentage of adherent granulocytes (Fig. 3A). Incubation of cytokine-activated mlEND cells with Antp-NBP also decreased the number of adherent granulocytes. Accordingly, NF-κB inhibition by both SLC1 treatment and Antp-NBP caused impaired transmigration of granulocytes across the activated endothelial cell layer (Fig. 3B).

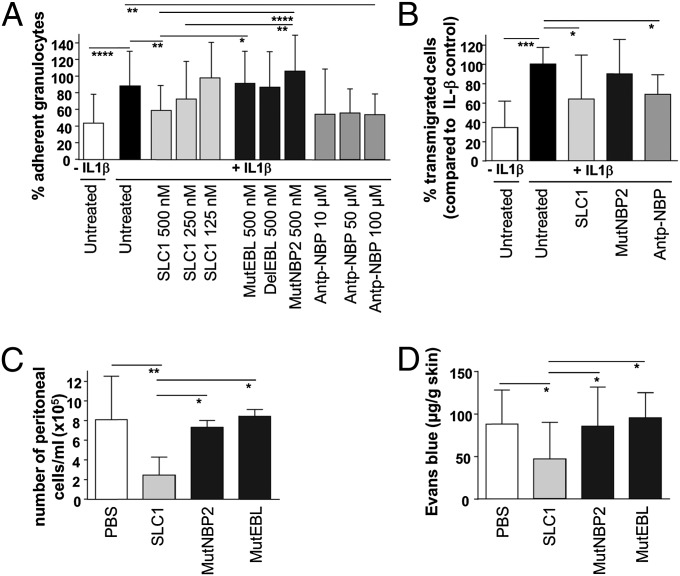

Fig. 3.

SLC1 reduces leukocyte–endothelium interactions in vitro and in vivo and prevents vascular leakage. (A) Granulocyte adhesion was reduced in SLC1-treated and cytokine-stimulated mouse endothelial cells (mlEND). Experiments were performed five times in triplicate. (B) In vitro transmigration of leukocytes through cytokine-activated mlENDs is inhibited by SLC1 application as well as by Antp-NBP. Experiments were performed five times in triplicate. (C) SLC1 application inhibited neutrophil migration in vivo in murine peritonitis. PBS, n = 9; SLC1, n = 10; MutNBP2, n = 5; MutEBL, n = 5. (D) Extravasation of Evans blue is prevented in cytokine-induced skin vessels in SLC1-treated mice. PBS, n = 8; SLC1, n = 10; MutNBP2, n = 5; MutEBL, n = 6. P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison posttest: ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. Error bars represent the ±SD.

To investigate whether a NF-κB blockade in endothelial cells alters leukocyte trafficking in vivo, we used a mouse model of acute thioglycollate-induced peritonitis. As shown in Fig. 3C, leukocyte influx into the peritoneal cavity of SLC1-treated mice was strongly reduced whereas equimolar doses of MutNBP2 and MutEBL did not exert significant effects. Hence, these data indicate that SLC1 inhibits inflammatory cell recruitment by blocking NF-κB in activated endothelial cells in vivo.

Because a leaky vasculature is a characteristic feature of inflammatory disorders (31), we also studied the modulatory potential of SLC1 on cytokine-induced increase of vascular permeability in vivo. As a surrogate for plasma extravasation, Evans blue was quantified in extracts of skin biopsies obtained from cytokine-exposed areas. Blockade of IKK2 in SLC1-treated mice resulted in significantly reduced vascular permeability compared with untreated, MutNBP2-, or MutEBL-treated mice (Fig. 3D).

In Vivo Imaging of SLC1 Binding to Cytokine-Activated Vascular Endothelium.

In vivo imaging was used to prove the selective binding of SLC1 to cytokine-activated but not to resting endothelium in vivo (29, 30). An epigastric vein in a cytokine-induced skin flap of live transgenic green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing mice was selected as the region of interest for SLC1 detection (Fig. S3A). Intraperitoneal injections of the infrared-labeled SLC1-FP635 into GFP mice did not lead to any change of the green fluorescent appearance of the nonactivated vasculature (Fig. 4A, Top). However, upon local cytokine challenge by the simultaneous injection of IL-1β and TNF-α (Fig. 4A, Middle), SLC1-FP632 (red) was localized to the vessel wall, resulting in an intensely stained orange border at the endothelial lining, which most likely reflects specific binding of SLC1 to E-selectin and subsequent internalization. Under identical conditions the systemically administered FP635-tagged DelEBL control construct did not accumulate in the vessel wall as reflected by the unchanged green fluorescent appearance of the cytokine-activated endothelial lining (Fig. 4A, Bottom). The luminal red fluorescence signal was detectable upon administration of FP635-labeled SLC1 and the FP635-DelEBL mutant under cytokine-activated but not under noninduced conditions (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3B). This observation was consistent in all mice and is most likely explained by reduced blood flow velocity and changes in the glycocalix of activated endothelial cells, promoting unspecific surface interactions with proteins. However, there was clearly no accumulation in the endothelial cell layer, as also shown by analysis of pixel intensities, which were calculated from distinct cross-sections at randomly selected positions along the axes of independent vessels. The grayscale pixel values of SLC1-FP635– and DelEBL-FP635–treated mice significantly differed at the vessel wall areas and clearly demonstrate selective accumulation of SLC1 in the endothelial layer (Fig. S3C).

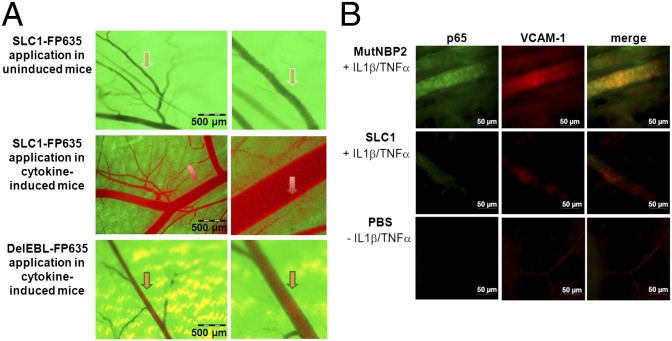

Fig. 4.

SLC1 binding to the vascular endothelium in vivo is dependent on its cytokine-activation status: inhibition of NF-κB activation. (A) Visualization of vessels in a nonactivated state (Top) exhibits the GFP-background fluorescence but no staining by the systemically administered red-fluorescent SLC1-FP635. Upon cytokine activation, the red fluorescent SLC1-FP635 accumulates in the vessel wall, leading to an intense orange staining (arrow, Middle) that is not detectable when the deletion mutant DelEBL-FP635 is administered (Bottom). Experiments were performed three times. (B) Representative images of whole-mount immunofluorescence skin sections stained for activated NF-κB p65 and VCAM-1. Experiments were performed three times.

Decreased NF-κB Activity in Cytokine-Activated Mouse Skin upon SLC1 Treatment.

Endothelial NF-κB activation was investigated ex vivo by whole-mount immunofluorescence microscopy of tissue specimens from cytokine-activated mouse skin upon double staining with a monoclonal antibody selectively binding to the activated, nuclear form of NF-κB p65 (32) and a VCAM-1–specific antibody. The adhesion molecule VCAM-1, which is strongly expressed due to cytokine-induced NF-κB activation, was stained simultaneously to identify the vascular endothelium. In addition, the amount of VCAM-1 expression reflects the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. Cytokine-induced nuclear NF-κB p65 staining in the vascular endothelium was strongly suppressed in mice pretreated with SLC1 but not in control mice that had received the MutNBP2 fusion protein (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, the skin of SLC1- but not of MutNBP2-pretreated mice exhibited a reduced endothelial VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 4B). Only weak VCAM-1 expression and no nuclear p65 staining were observed in nonactivated skin. These observations were confirmed by quantifying the mean fluorescence intensities of p65 and VCAM-1 stainings (Fig. S3D). Thus, our data indicate that a systemically administered NF-κB inhibitor targeting E-selectin suppresses endothelial NF-κB activation and concomitant VCAM-1 expression in a cytokine-induced inflammatory response in vivo.

NF-κB Inhibition in Endothelial Cells Ameliorates Experimental Arthritis.

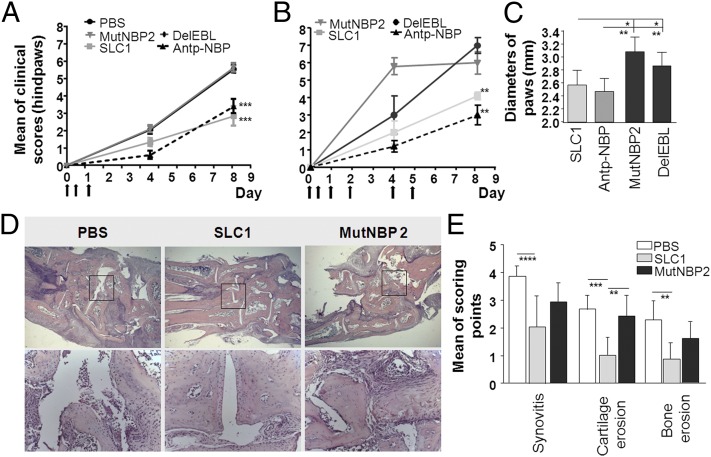

Next, we asked whether NF-κB activation in endothelial cells is critically involved in the pathogenesis of serum transfer arthritis (STIA) (33) and antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) (34). In the STIA model, injection of serum from K/BxN mice containing antibodies against glucose-6-phosphoisomerase (anti-G6PI) causes an acute polyarthritis. The aggressive STIA shares many features with human RA, including polyarticular manifestation, leukocyte invasion, pannus formation, synovitis, as well as cartilage and bone erosions (33). Mice were intraperitoneally injected with the autoantibody-containing serum and the SLC proteins (100 µg/injection). SLC application was repeated after 7 and 24 h. Under the same conditions we examined the effect of Antp-NBP (200 µg/injection) in STIA. The clinical arthritis scores were significantly lower in SLC1-treated mice compared with PBS-, MutNBP2-, and DelEBL-treated mice. The therapeutic effect of SLC1 was comparable to Antp-NBP (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Clinical and histological manifestations are ameliorated in the K/BxN serum transfer model after SLC1 treatment. (A) Mice were three times treated with 100 µg SLCs or 200 µg Antp-NBP as indicated by arrows. PBS, n = 19; SLC1, n = 13; MutNBP2, n = 9; DelEBL, n = 5; Antp-NBP, n = 5. (B) Treatments with the indicated SLCs or Antp-NBP were continued on days 2, 4, and 5. SLC1, n = 10; MutNBP2, n = 10; DelEBL, n = 10; Antp-NBP, n = 10. (C) On day 8 diameters of paws (paw and ankle) were measured. (D) Representative microphotographs of H&E-stained sections at day 8 after K/BxN serum transfer. (E) Histological analyses of synovitis, cartilage, and bone erosions. P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison post test: ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

The extension of SLC1 or Antp-NBP treatments by additional applications at days 2, 4, and 5 did not result in more pronounced reduction of disease severity (Fig. 5B). These data are in line with SLC1 acting as an inhibitor of extravasation in the early phase of inflammation. Joint swelling was assessed by measuring the diameters of paws and ankles as shown in Fig. 5C. Swelling was significantly reduced in mice treated with SLC1 or Antp-NBP compared with the control groups. At the end of the experiment, hindpaws were analyzed by histology. SLC1 application resulted in suppressed cartilage and bone degradation, as well as reduced synovial inflammation (Fig. 5 D and E).

AIA is induced by intra-articular injection of methylated BSA into the knee joints of mice immunized with methylated BSA, resulting in an acute monoarthritis lasting approximately 1 wk. During the chronic phase of AIA, intra-articular methylated BSA injection causes a flare-up reaction of arthritis. Intraperitoneal application of SLC1 resulted in reduced joint swelling during the acute (Fig. S4A) as well as flare-up phase (Fig. S4B) compared with control mice treated with solvent, DelEBL, or MutNBP2. Histological analyses supported the clinical findings. Joints of SLC1-treated mice exhibited the normal appearance of a thin synovial lining layer with only a sparse infiltration by inflammatory cells (indicated by the arrows) compared with the hyperplastic synovium with diffuse infiltrations of numerous leukocytes in PBS-treated mice (Fig. S4 C and D). These results indicate that NF-κB activation within endothelial cells is a crucial event in the pathogenesis of experimental models for RA.

Discussion

A hallmark of inflammation in autoimmune disorders such as RA is the activation of the classical NF-κB pathway. Accordingly, targeting NF-κB for anti-inflammatory intervention has been successfully demonstrated in multiple animal models during past years (10, 24, 35). However, systemic interference with NF-κB activation influences a variety of homeostatic regulatory pathways in, for example, the liver and the immune system (16). Ubiquitous pharmacologic suppression of NF-κB activity may therefore lead to severe side effects including profound immunosuppression, liver cell apoptosis, and organ dysfunctions (16, 17, 36). The SLC approach is likely to have an improved risk–benefit ratio compared with a general NF-κB inhibition (16, 17, 36, 37). As NF-κB is also involved in the resolution of inflammation, systemic inhibition of its activity can even promote chronic inflammation depending on the cell type and the disease phase (12, 38). Moreover, IKK2 can exert direct anti-inflammatory properties via inhibition of classical macrophage activation and counteraction of IL-1β secretion. Hence, IKK2 is critical to prevent IL-1β–driven neutrophilia (39). Therefore, a more efficient and safer therapy should target selectively those cell types in which NF-κB actually contributes to the pathogenesis of a certain disease. In this regard, the vascular endothelium is a selective barrier between blood and tissue and represents a checkpoint for extravasation of plasma proteins and inflammatory cells, preventing or allowing transmigration of neutrophils, monocytes, and T and B lymphocytes into the sites of inflammation (3, 4).

Toward a better understanding of the role of NF-κB in the activated endothelium in experimental models of inflammation, we developed a tool to manipulate NF-κB activity selectively in activated endothelial cells. For targeting, E-selectin has been chosen due to its NF-κB–dependent transcriptional up-regulation in the early phase of cytokine activation and its internalization upon ligation (40, 41).

“Sneaking ligand” refers to the contribution of the ETAII domain to the SLC1 function, i.e., to promote the translocation of the NEMO-binding effector domain from the endosomal compartment into the cytosol to achieve NF-κB blockade (28). Single-chain variable fragment immunotoxins were successfully used to selectively kill cancer cells, indicating that the endosomal release function of the ETAII domain is not compromised in chimeric proteins (42). The essential role of the translocation domain in our sneaking-ligand principle is demonstrated by the inability of the DelETA to inhibit NF-κB activation. Our investigations provide unequivocal evidence for the crucial role of SLC1 interaction with surface E-selectin for targeted cellular uptake. Thus, mutants of SLC1 harboring an intact NEMO-binding domain but lacking the E-selectin–interacting module failed to block NF-κB in E-selectin–expressing CHO cells in vitro. Upon systemic application in mice the deletion mutant DelEBL, in contrast to the full-length SLC1, did not accumulate in the endothelial layer of a cytokine-activated vasculature.

SLC1 interfered with leukocyte binding and neutrophil migration in vitro and in vivo. The crucial involvement of NF-κB inhibition is supported by control experiments with Antp-NBP and MutEBL that render alternative explanations for the mechanism of SLC1 action such as masking of E-selectins or their down-regulation unlikely.

The anti-inflammatory effects of an NF-κB blockade in endothelial cells was shown in two different models of arthritis. Inhibition of IKK2 in endothelial cells efficiently controlled monoarticular arthritis in AIA as well as polyarticular arthritis in STIA. Remarkably, the effective molar concentration of SLC1 was 20-fold less than the concentration of Antp-NBP. Histological data confirmed the SLC1-dependent anti-inflammatory effect and demonstrated that endothelial specific inhibition of NF-κB protected cartilage and bone against inflammation-induced structural damage. These results define the critical role of endothelial NF-κB activation in arthritis and are consistent with experiments blocking endothelial adhesion molecules, which ameliorated collagen-induced arthritis (3, 14). The essential role of the NBP effector domain was confirmed with constructs that contain an intact E-selectin–binding domain together with a nonfunctional NBP (MutNBP2). These mutants lost their ability to block NF-κB activation in vitro as well as in vivo and also lacked anti-inflammatory activity in AIA and STIA in vivo despite their intact E-selectin–binding domain.

Changes in vascular permeability represent a common feature of inflammatory responses. We observed a decreased vascular leakage in SLC1-treated mice, demonstrating that NF-κB activation via the classical pathway is critical for an increased vascular permeability. Our results are in accordance with a study showing the reduction of LPS-mediated vascular permeability in endothelial cells by interference with NF-κB activation using transgenic overexpression of IκBα (43). In contrast, Ashida and colleagues described increased vascular permeability in endothelial-specific IKK2-deficient mice. Increased vascular permeability was due to kinase-independent effects of IKK2 (25). Therefore, the use of SLC1 appears to be more specific than the investigation of IKK2-deficient cells in investigating NF-κB–dependent effects.

In summary, our study establishes that NF-κB activation within endothelial cells is a crucial step in the pathogenesis of experimental models of RA. Disruption of the IKK complex in endothelial cells efficiently controls the extravasation of inflammatory cells in arthritis models and might represent a treatment strategy in RA. The potential immunogenicity of SLC1 may impede long-term treatments. To decrease immunogenicity, we are currently developing sneaking ligands predominantly based on endogenous proteins. Thus, we have developed a tool to study the role of intracellular signaling pathways in specific cell types contributing to the pathogenesis of diseases. The present investigation reports the in vivo efficacy of a cell type-specific guided NF-κB inhibition specifically targeting the activated endothelium at sites of inflammation and selectively blocking a crucial proinflammatory intracellular signaling cascade. Thus, this approach is applicable as an anti-inflammatory strategy that maintains the essential homeostatic functions of NF-κB while selectively interfering with its activation in the inflamed endothelium. Considering the importance of endothelial NF-κB activation in pathophysiological conditions including septic shock (44), procoagulant states such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (45), atherogenesis (46), or tumor neoangiogenesis (47), the therapeutic potential with SLC1 is likely much broader.

The “sneaking ligand concept” is easily transferable to target other cell types and signaling pathways by the exchange of the binding and effector domains. Hence, this study demonstrates a promising strategy to identify disease-relevant signaling pathways in defined cell types.

Materials and Methods

A detailed description of materials and methods is provided as SI Materials and Methods.

Cloning of Plasmids Expressing E-Selectin–Specific Sneaking Ligands.

Nucleotide sequences corresponding to the E-selectin–specific peptide AF 10166 (22) or the scrambled peptide AF 11678 (22), the ETA II domain (amino acid 253–364) (23), and the NBP (amino acids 644–756 from IKK2) (24) and mutated NBP (24) were connected via glycine–serine linkers. Sequences of the designed gene were codon optimized for E. coli expression, synthesized (Bio&Sell), and cloned into pAK400 (26) via SfiI. For in vivo imaging experiments as well as for confocal microscopy, an infrared-fluorescent tag FP635 (mKATE) (30) was cloned behind the NBP domain.

Mouse Models.

K/BxN serum transfer arthritis (33), antigen-induced arthritis (34), or thioglycollate-induced peritonitis were induced as described and used to analyze the therapeutic efficacy of the SLCs or Antp-NBP.

In Vitro Experiments.

Neutrophil adhesion and transmigration through SLC1-treated and cytokine-stimulated mouse endothelial cells were performed. Inhibition of NF-κB activation was investigated using NF-κB luciferase reporter assay and EMSA. Whole-mount immunofluorescence technique was used to identify activated p65 and VCAM-1 in SLC-treated mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniela Graef, Elvedina Nendel, Eugenia Scheffler, Rita Rzepka, Olga Greb, and Ina Stumpf for excellent technical assistance. mlEND cells were kindly provided by Dr. Ruppert Hallmann. We thank Dr. Frank Emmerich for coining the name “sneaking ligand” and Dr. Olaf Broders and Dr. Bernd Voedisch for their supportive work. We also thank Winfried Wels. This research was supported by the German Research Foundation (SFB 643 project B3 and A8; FOR 832, project 7; Sachbeihilfe DU337/3-2 and BU 584/4-1); BMBF 01EO0803 Grant to the Centre of Chronic Immunodeficiency; the Doktor-Robert Pfleger Stiftung; the Interdisciplinary Center of Clinical Research of the University Erlangen; the FP7 funding of the European Union (Masterswitch); the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research ArthroMark (project 4, 01 EC 1009C); the Federal State of Hessen (LOEWE-Project: Fraunhofer IME-Project-Group Translational Medicine and Pharmacology, Goethe University Frankfurt); and National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1HL096642.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. F.R.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1218219110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Williams MR, Azcutia V, Newton G, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW. Emerging mechanisms of neutrophil recruitment across endothelium. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(10):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denk A, et al. Activation of NF-kappa B via the Ikappa B kinase complex is both essential and sufficient for proinflammatory gene expression in primary endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(30):28451–28458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oppenheimer-Marks N, Lipsky PE. Adhesion molecules as targets for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;79(3):203–210. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(10):803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden MS, West AP, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB and the immune response. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6758–6780. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempe S, Kestler H, Lasar A, Wirth T. NF-kappaB controls the global pro-inflammatory response in endothelial cells: Evidence for the regulation of a pro-atherogenic program. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(16):5308–5319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregersen PK, et al. REL, encoding a member of the NF-kappaB family of transcription factors, is a newly defined risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):820–823. doi: 10.1038/ng.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmonds RE, Foxwell BM. Signalling, inflammation and arthritis: NF-kappaB and its relevance to arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(5):584–590. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makarov SS. NF-kappa B in rheumatoid arthritis: A pivotal regulator of inflammation, hyperplasia, and tissue destruction. Arthritis Res. 2001;3(4):200–206. doi: 10.1186/ar300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voll RE, Mikulowska A, Kalden JR, Holmdahl R. Amelioration of type II collagen induced arthritis in rats by treatment with sodium diethyldithiocarbamate. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(6):1352–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tas SW, et al. Local treatment with the selective IkappaB kinase beta inhibitor NEMO-binding domain peptide ameliorates synovial inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R86. doi: 10.1186/ar1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence T, Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willoughby DA. Possible new role for NF-kappaB in the resolution of inflammation. Nat Med. 2001;7(12):1291–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clavel G, et al. Relationship between angiogenesis and inflammation in experimental arthritis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17(3):202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasgupta B, Chew T, deRoche A, Muller WA. Blocking platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM) inhibits disease progression and prevents joint erosion in established collagen antibody-induced arthritis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88(1):210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanaugh A. Adhesion molecules as therapeutic targets in the treatment of allergic and immunologically mediated diseases. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;80(3 Pt 2):S15–S22. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uwe S. Anti-inflammatory interventions of NF-kappaB signaling: Potential applications and risks. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(8):1567–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(2):135–142. doi: 10.1172/JCI11914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavanaugh AF, et al. Treatment of refractory rheumatoid arthritis with a monoclonal antibody to intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(7):992–999. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gareus R, et al. Endothelial cell-specific NF-kappaB inhibition protects mice from atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;8(5):372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SH, et al. Myeloid-specific IκB kinase β deficiency decreases atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(12):2869–2876. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.254573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gullick NJ, Scott DL. Co-morbidities in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(4):469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martens CL, et al. Peptides which bind to E-selectin and block neutrophil adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(36):21129–21136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wick MJ, Hamood AN, Iglewski BH. Analysis of the structure-function relationship of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4(4):527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.May MJ, et al. Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by a peptide that blocks the interaction of NEMO with the IkappaB kinase complex. Science. 2000;289(5484):1550–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashida N, et al. IKKβ regulates essential functions of the vascular endothelium through kinase-dependent and -independent pathways. Nat Commun. 2011;2:318. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebber A, et al. Reliable cloning of functional antibody variable domains from hybridomas and spleen cell repertoires employing a reengineered phage display system. J Immunol Methods. 1997;201(1):35–55. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May MJ, Marienfeld RB, Ghosh S. Characterization of the Ikappa B-kinase NEMO binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(48):45992–46000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weldon JE, Pastan I. A guide to taming a toxin: Recombinant immunotoxins constructed from Pseudomonas exotoxin A for the treatment of cancer. FEBS J. 2011;278(23):4683–4700. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seitz G, et al. Imaging of cell trafficking and metastases of paediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Cell Prolif. 2008;41(2):365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shcherbo D, et al. Bright far-red fluorescent protein for whole-body imaging. Nat Methods. 2007;4(9):741–746. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson SE, Lexmüller K, Ekström GM. Physiological characterization of mBSA antigen induced arthritis in the rat. I. Vascular leakiness and pannus growth. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(9):1772–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zabel U, Henkel T, Silva MS, Baeuerle PA. Nuclear uptake control of NF-kappa B by MAD-3, an I kappa B protein present in the nucleus. EMBO J. 1993;12(1):201–211. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji H, et al. Arthritis critically dependent on innate immune system players. Immunity. 2002;16(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brackertz D, Mitchell GF, Mackay IR. Antigen-induced arthritis in mice. I. Induction of arthritis in various strains of mice. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20(3):841–850. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tas SW, et al. Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB in dendritic cells by the NEMO-binding domain peptide blocks maturation and prevents T cell proliferation and polarization. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(4):1164–1174. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auphan N, DiDonato JA, Rosette C, Helmberg A, Karin M. Immunosuppression by glucocorticoids: Inhibition of NF-kappa B activity through induction of I kappa B synthesis. Science. 1995;270(5234):286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Acquisto F, May MJ, Ghosh S. Inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-B): An emerging theme in anti-inflammatory therapies. Mol Interv. 2002;2(1):22–35. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanters E, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activation in macrophages increases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(8):1176–1185. doi: 10.1172/JCI18580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu LC, et al. IL-1β-driven neutrophilia preserves antibacterial defense in the absence of the kinase IKKβ. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(2):144–150. doi: 10.1038/ni.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setiadi H, McEver RP. Clustering endothelial E-selectin in clathrin-coated pits and lipid rafts enhances leukocyte adhesion under flow. Blood. 2008;111(4):1989–1998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Asmuth EJ, et al. Evidence for endocytosis of E-selectin in human endothelial cells. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22(10):2519–2526. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwemmlein M, et al. A CD19-specific single-chain immunotoxin mediates potent apoptosis of B-lineage leukemic cells. Leukemia. 2007;21(7):1405–1412. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tiruppathi C, et al. Role of NF-kappaB-dependent caveolin-1 expression in the mechanism of increased endothelial permeability induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(7):4210–4218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703153200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu SF, Malik AB. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(4):L622–L645. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu H, Ye X, Steinberg H, Liu SF. Selective blockade of endothelial NF-kappaB pathway differentially affects systemic inflammation and multiple organ dysfunction and injury in septic mice. J Pathol. 2010;220(4):490–498. doi: 10.1002/path.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins T, Cybulsky MI. NF-kappaB: Pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis? J Clin Invest. 2001;107(3):255–264. doi: 10.1172/JCI10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naugler WE, Karin M. NF-kappaB and cancer-identifying targets and mechanisms. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.