Abstract

For the first time the far red fluorescent protein (FP) E2-Crimson genetically expressed in the exocrine pancreas of adult zebrafish has been non-invasively mapped in 3D in vivo using photoacoustic tomography (PAT). The distribution of E2-Crimson in the exocrine pancreas acquired by PAT was confirmed using epifluorescence imaging and histology, with optical coherence tomography (OCT) providing complementary structural information. This work demonstrates the depth advantage of PAT to resolve FP in an animal model and establishes the value of E2-Crimson for PAT studies of transgenic models, laying the foundation for future longitudinal studies of the zebrafish as a model of diseases affecting inner organs.

OCIS codes: (170.3880) Medical and biological imaging; (170.5120) Photoacoustic imaging; (170.6280) Spectroscopy, fluorescence and luminescence; (170.6960) Tomography

1. Introduction

Fluorescent proteins (FP) have brought revolutionary advances in life sciences by enabling structural and functional studies in living cells and organisms [1]. While confocal and multiphoton microscopy have traditionally been used to visualize FP [2], several optical imaging methods have been developed to overcome the imaging depth limit set by the transport mean free path length (<1 mm), such as selective plane illumination microscopy (SPIM) [3], ultramicroscopy [4], optical projection tomography (OPT) [5] and fluorescence lifetime OPT (FLIM-OPT) [6]. Though SPIM and ultramicroscopy yield improved axial resolutions and reduced photobleaching compared to confocal or multiphoton microscopy, they are limited to fluorescence imaging. OPT can be used to get absorption information and fluorescence distribution, but it is still strongly limited by the tissue scattering and therefore requires an optically transparent sample or optical clearing of biological samples, making it invasive in some applications.

A rapidly developing three dimensional (3D) imaging modality–photoacoustic tomography (PAT)–offers the possibility to reconstruct the FP distribution in 3D beyond the transport mean free path length with high spatial resolution. It uses the photoacoustic effect, in which chromophores absorb short laser pulse energies, the absorbed energy is converted to heat and acoustic pulses – photoacoustic waves – are subsequently generated [7, 8]. The detection of the photoacoustic waves generally occurs via piezoelectric transducers. However, the delivery of excitation laser pulses is difficult as the transducer or transducer array is generally opaque. Furthermore, larger element sizes of the transducer give better sensitivities while smaller element sizes are preferred for accurate PAT image reconstruction. To address these issues, an optical detection PAT system that replaces piezoelectric transducers with a Fabry-Perot polymer film sensor interrogated by a focused laser beam over its surface [9] has been shown to give comparable sensitivity while enabling backward mode illumination for deep tissue imaging [10]. Multiple in vivo applications of the optical detection PAT system have demonstrated a sub-100-micron spatial resolution with a penetration depth of almost 10 mm [11, 12].

Using the wavelength dependence of chromophore absorption of laser pulses, different chromophores will contribute to the photoacoustic signals in PAT when the excitation wavelength changes, making the reconstruction of a specific type of chromophore possible using spectroscopic PAT [13]. This makes PAT a suitable solution for resolving the specific cell types tagged in vivo by FP, which in turn broadens the potential application of PAT in preclinical research taking into consideration that many disease models depend on the detection of optically neutral cell types. Among all the available animal models, one important vertebrate organism where PAT imaging could be extremely beneficial is the zebrafish, where transgene driven expression of FP under tissue specific promoters can be used as a quantifiable indicator of endogenous cell populations. A well-established model in cancer [14–16], tissue regeneration [17–19] and tissue vascularization [20] research, the zebrafish has been imaged both as a larva by photoacoustic microscopy (PAM) [21] and as an adult fish using PAT [22]. From these studies, it has been shown that with a width of about 10 mm and a length of about 60 mm, adult zebrafish provide a unique opportunity for 3D whole-body PAT scanning.

In this work, we report the use of an E2-Crimson transgene in spectroscopic PAT for 3D in vivo visualization of the exocrine pancreas of an adult zebrafish. This confirms the in vivo applicability of E2-Crimson in PAT using a transgenic zebrafish line expressing this protein in its exocrine pancreas, whose capacity for regeneration makes it valuable for inner organ disease model studies. Since combined PAT and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) systems have been shown to provide complementary information [23–28], SD-OCT images along with histological sections and fluorescence images are also presented for comparison. To our knowledge, this is the first report in which a far-red FP is imaged in vivo by spectroscopic PAT.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental setup

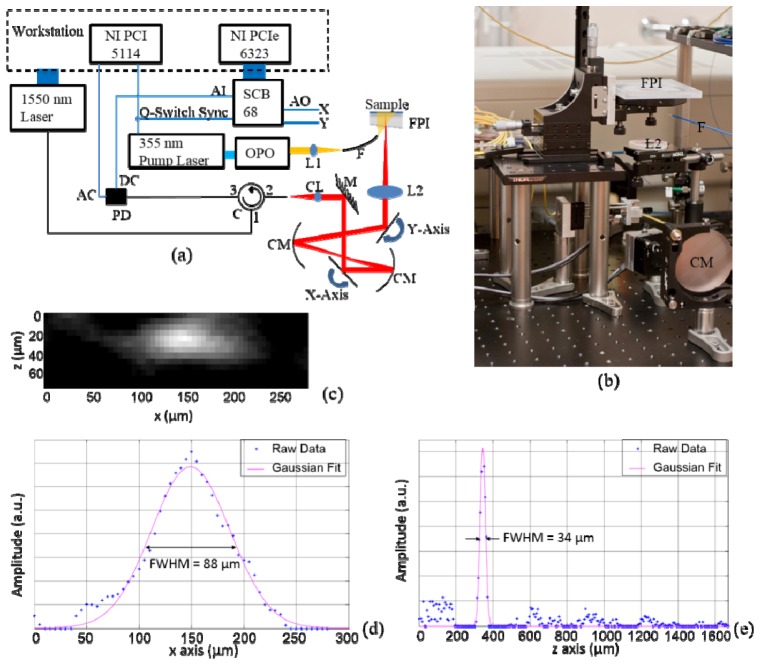

The schematic of the optical detection PAT system is given in Fig. 1(a) with a photograph of the scanning unit in Fig. 1(b). For a detailed description of detection principles, the reader is referred to [10, 29]. Throughout the experiment, an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) (versaScan, GWU) with a 50 Hz repetition rate pumped by a pulsed Nd:YAG laser (Quanta-Ray PRO-270-50, Spectra-Physics) was used as the excitation source. A 2D pixel-by-pixel scan over the Fabry-Perot polymer film sensor using a CW laser was enabled by two scanning mirrors (6210H, Cambridge Technology) whose scanning pattern was controlled by the analog output of a data acquisition card with an analog generation function (NI PCIe-6323, National Instruments), while the wavelength of the CW laser was tuned to the optimum bias for each pixel during the scan. The modulated reflected intensity of the CW beam from the polymer film sensor, which linearly corresponds to the photoacoustic pulse, was acquired by a digitizer (NI PCI 5114, National Instruments) at 250 MS/s from the AC channel of the photodiode. The 2D scan over the sensor and the data acquisition were synchronized by the Q-Switch Sync signal from the pump laser. No averaging was used during data acquisition. The system resolution was experimentally determined by imaging an absorbing inked fiber of less than 2 µm diameter to be 34 µm axially and 88 µm laterally close to the surface of the polymer film sensor.

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic of the PAT system. AI: analog input; AO: analog output; SCB 68: the connector block for NI PCIe 6323; FPI: Fabry-Perot interferometer polymer film sensor; PD: photodiode; C: circulator; CM: concave mirror; CL: collimator; L1: focusing lens for OPO output; L2: objective lens; F: multimode fiber delivering the excitation laser beam; M: mirror. (b) A photograph of the scanning unit of the PAT system. (c) A reconstructed cross section of the inked fiber imaged using the PAT system with z axis being the depth dimension and x axis the lateral dimension. (d) A plot through the center of the inked fiber shown in (c). Gaussian fitting to the raw data points was performed and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the fitted curve represents the lateral resolution of the system. (e) Similar to (d), but in the axial direction.

For details regarding the SD-OCT system, see [30, 31]. Briefly, a custom SD-OCT system in the 1300 nm range with 100 nm bandwidth was used. The system has a lateral resolution of 20 µm, an axial resolution of 8 µm and an imaging speed of 46 frames/s. Each B-scan covers 7 mm × 1.5 mm (1024 × 1024 voxels). Multiple frames can be mosaiced together to cover a larger scanning range. The power incident upon the sample was 7 mW which is well below the safety limit [32].

2.2 Zebrafish preparation and imaging sequence

An adult transgenic zebrafish expressing E2-Crimson under control of the exocrine pancreas specific elastase 3l promoter (Tg(ela:E2crimson/DTR)) [33, 34] with the stripes genetically knocked out was anesthetized using tricain [35]. Epifluorescence images of the fish were then taken using a fluorescence microscope (MZ 16F, Leica) before it was placed right side down on top of the polymer film sensor for PAT scanning. Distilled water was used as the acoustic couplant in which the fish was placed. After the PAT scan, the fish was removed from the sensor and placed into a water filled cuvette for the SD-OCT scanning. In the end, the fish was euthanized, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified in BOUIN’s fluid for 10 days, embedded in paraplast wax and serially sectioned for histological studies where 10 µm thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

2.3 PAT Scanning procedure and image reconstruction

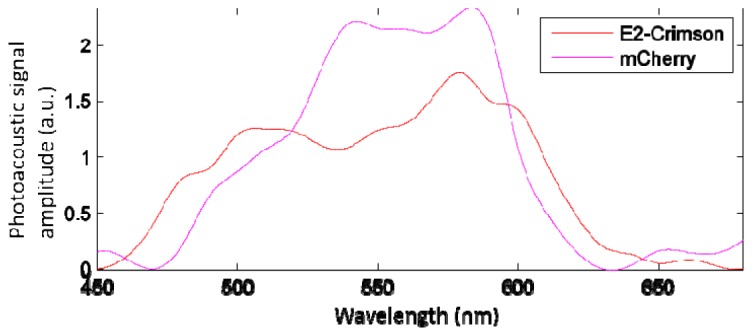

Figure 2 shows the photoacoustic spectra of E2-Crimson and mCherry [36]. Two excitation wavelengths that fell within the passband limits of our polymer film sensor were used – 611 nm and 640 nm – with one scan at each wavelength. An area of 6 mm × 14 mm, covering most of the body of the fish, was scanned with a 50 µm scan step size in both dimensions. The scan step size was selected as a tradeoff of the total acquisition time and the system resolution. Each scan took about 12 minutes and the entire experiment lasted about 30 minutes including the time required for animal preparation and the manual tuning of the excitation wavelength. The excitation laser intensity was measured to be well below the safety limit of 20 mJ/cm2 [32]. This study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Innsbruck and all procedures complied with animal care regulations.

Fig. 2.

Photoacoustic spectra of E2-Crimson and mCherry, adapted from [36].

Initial image reconstruction for each wavelength was performed using the k-space (FFT) algorithm of the k-Wave toolbox for MATLAB (version 2010a, the MathWorks, Inc.) [37] followed by a moving average filter applied in the sagittal direction for noise reduction. Multispectral processing for the E2-Crimson mapping was achieved using a linear regression model on a per pixel basis assuming the contribution to the photoacoustic signal at each pixel being from the E2-Crimson and a general background which is described in detail in [38]. The corresponding coefficients of E2-Crimson at 611 nm and 640 nm were acquired from Fig. 2, so that the photoacoustic spectrum of E2-Crimson, instead of a molar extinction spectrum, was used for more accurate processing.

3. Results

3.1 Maximum amplitude projection images of PAT and SD-OCT

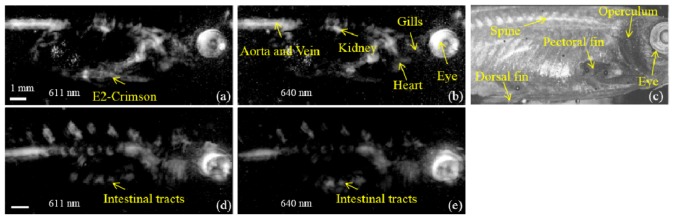

The maximum amplitude projection (MAP) PAT images of the E2-Crimson expressing zebrafish from the two wavelengths are given in Fig. 3(a) and Fig. 3(b). Inner organs and structures such as the kidney, the heart, the gills, the eye and the dorsal aorta and vein can be clearly discerned. Figure 3(d) and 3(e) are images of a negative control fish from the same fish line that does not express any FP in the exocrine pancreas, but was also imaged using both wavelengths. A comparison between the E2-Crimson expressing fish MAP images and the control fish images gives a clear indication that the E2-Crimson labeled exocrine pancreas, which is in the ventral part of the abdomen of the fish, is missing in the control fish. The control fish imaging is also useful in that it can be used to provide an estimation of the background absorption information for multispectral processing. Figure 3(c) is the MAP image acquired by SD-OCT. Compared to its PAT counterparts whose contrast is governed by absorption differences, SD-OCT, with its back-reflection induced contrast, clearly shows structures such as the operculum, the spine and the fins which do not appear in the PAT MAP images, providing additional structural information.

Fig. 3.

Maximum amplitude projection (MAP) images of the E2-Crimson expressing zebrafish acquired at 611 nm (a) and 640 nm (b) displayed over 18 dB dynamic range. (c) is an SD-OCT MAP image of the E2-Crimson expressing fish. (d) and (e) are MAP images of a negative control fish imaged at 611 nm and 640 nm, respectively.

3.2 2D E2-Crimson mapping using spectroscopic PAT and epifluorescence microscopy

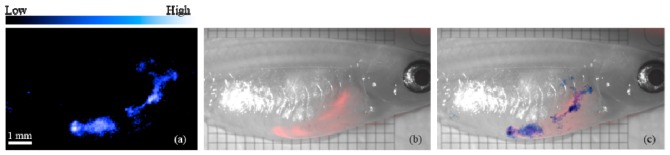

In addition to the MAP images given in Fig. 3, for the same fish, the whole exocrine pancreas labeled by E2-Crimson was projected in the sagittal direction after multispectral processing, which is then compared with the epifluorescence image of the fish taken just before the PAT scan. Figure 4(a) maps E2-Crimson acquired by spectroscopic PAT in blue. Figure 4(b) is the epifluorescence image showing E2-Crimson in red. An overlay of Fig. 4(a) and Fig. 4(b) is given in Fig. 4(c) with the scale and dimension corrected using the reticle placed beneath the zebrafish in Fig. 4(b). Figure 4(c) clearly demonstrates the close correspondence of the FP distribution acquired in epifluorescence microscopy and by spectroscopic PAT.

Fig. 4.

(a) E2-Crimson distribution (blue) acquired by spectroscopic PAT. (b) Epifluorescence photo of the adult zebrafish showing E2-Crimson (red). (c) Overlay of (a) and (b).

3.3 3D E2-Crimson distribution acquired by spectroscopic PAT

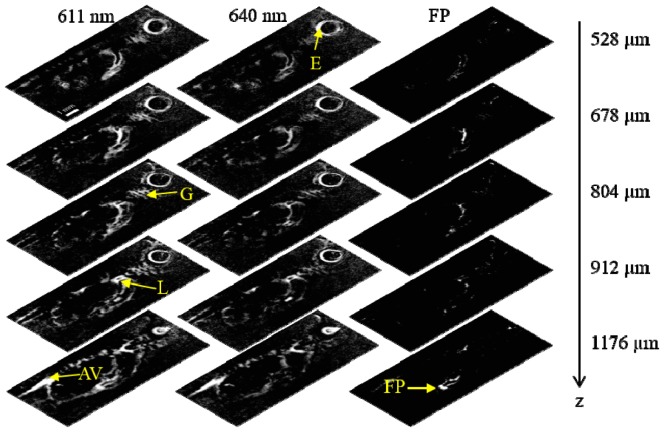

Since PAT is inherently a 3D imaging modality, we also used multispectral processing to map the E2-Crimson distribution over depth for the same E2-Crimson expressing fish. Figure 5 shows five representative sagittal slices at depths of 528 µm, 678 µm, 804 µm, 912 µm and 1176 µm with the left, middle and right columns being the slices at 611 nm, 640 nm and the multispectral processed slices for the exocrine pancreas, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Sagittal sections of the zebrafish using PAT at five representative depths. Left and middle columns use the data acquired at 611 nm and 640 nm, respectively. The right column shows the multispectral processed results with the exocrine pancreas labeled by E2-Crimson. E: eye; G: gills; FP: fluorescent protein labeled exocrine pancreas; L: liver; AV: aorta and vein.

A comparison between the left and middle columns of Fig. 5 shows that the eye and the gills are present in all the depths while the aorta and the intersegmental vessels are better resolved in deeper sections. The exocrine pancreas, however, bears gradual changes in deeper sections, which is easily visualized in the right column. In the last image of the right column, the fine structures of the exocrine pancreas that strides over the intestinal tracts are resolved.

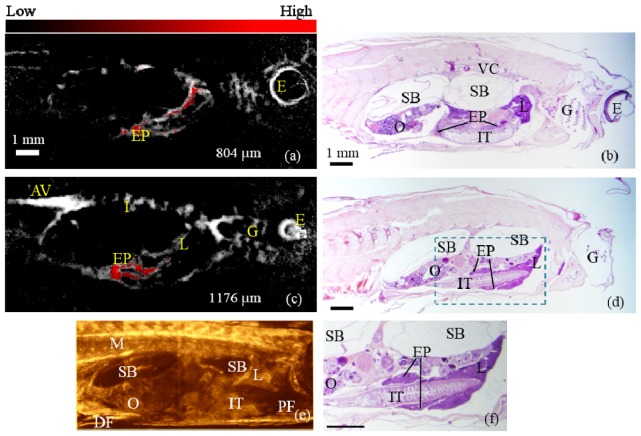

3.4 Confirmation by histological images

For the same fish, Fig. 6(a) and Fig. 6(c) show two representative slices of PAT at the depths of 804 µm and 1176 µm imaged at 611 nm with the multispectral processed exocrine pancreatic region overlaid. Histological sections of the same fish from approximately corresponding depths are provided in Fig. 6(b) and Fig. 6(d). The gills, the eye and the aorta and vein acquired in PAT match well with those given in the histological images. The FP labeled exocrine pancreas imaged by PAT also bears a close match to that resolved in the histological images at the different depths. The dual-band structure of the exocrine pancreas seen in Fig. 6(c) (PAT) is well confirmed by that seen in Fig. 6(f) (histology), which is a zoomed-in display of the dashed region in Fig. 6(d). Figure 6(e) is an SD-OCT B-mode image at approximately corresponding position to that of Fig. 6(c). Structures not resolvable in PAT, such as the swim bladder, the ovary, the pectoral and dorsal fins, the muscle and the intestinal tracts, are distinguishable in SD-OCT, again demonstrating the complementary information SD-OCT may provide to PAT. The slight offset between PAT and the histological images is likely due to the tissue changes during fixation for histology.

Fig. 6.

(a) & (c): PAT images acquired at the depths of 804 µm and 1176 µm, respectively with the FP labeled exocrine pancreas processed from spectroscopic PAT overlaid in red. (b) & (d): Histological sections at approximate depths as (a) and (c), respectively. (e) is an SD-OCT B-mode image of the zebrafish at approximately corresponding depth to (c). (f) is a zoomed-in display of the dashed region in (d). EP: exocrine pancreas; M: muscle; DF: dorsal fin; PF: pectoral fin; E: eye; AV: aorta and vein; G: gills; I: intersegmental vessels; VC: vertebral column; SB: swim bladder; O: ovary; IT: intestinal tracts; L: liver.

4. Discussion

The visualization of FP using photoacoustic imaging has been explored in other studies. One resolved a bacteriophytochrome-based near-infrared FP (iRFP) in a mouse tumor xenograft model, and the iRFP-expressing tumor was successfully detected with 100 µm transversal resolution in the subcutaneous region [39]. A deep-photoacoustic microscopy (deep-PAM) setup was also used to image the iRFP and it was claimed the best available genetically encoded probe in terms of depth versus resolution [39, 40].

In zebrafish, one spectroscopic PAT study showed the distribution of the FP mCherry in the central nervous system (CNS) of an adult zebrafish after performing multispectral processing of the photoacoustic images acquired at multiple wavelengths [38]. The zebrafish had to be held in an agar phantom or embedded in modeling clay, in contrast to our study where the zebrafish was simply placed in water on top of the polymer film sensor. More importantly, however, the multispectral processing in their study relied on the molar extinction spectrum of mCherry instead of its photoacoustic spectrum, which is substantially different. This means the multispectral processing could be inaccurate. In addition, mCherry shows much less photostability than E2-Crimson, which raises concern for its applicability in spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging where several tens of thousands of pulses may be required for whole-body scanning with multiple excitation wavelengths. Ref [36] studied the photobleaching features of mCherry and E2-Crimson in a static model using fluorescent proteins in solution, and the mCherry-induced photoacoustic signal amplitude decreased by approximately 50% in about 30000 pulses with a fluence between 1.5 – 1.7 mJ/cm2. On the contrary, E2-Crimson not only had better absorption in the range of 600 – 640 nm, but also gave almost constant photoacoustic signal amplitude over prolonged exposure to excitation pulses. When considering that the “biologically transparent window” in which light can penetrate deeper into tissue does not start until 600 nm [1], E2-Crimson has its advantages in photoacoustic imaging applications due to its prolonged photostability and better absorption.

Furthermore, compared to non-fluorescent chromoproteins such as cjBlue and aeCP597 which were recommended for PAT imaging [36], E2-Crimson is applicable for fluorescence based follow up studies such as fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) or high resolution 3D-confocal image analysis. The fast decay of the E2-Crimson photoacoustic spectrum above 600 nm also makes it suitable for our Fabry-Perot polymer film sensor whose passband starts at 600 nm.

In Fig. 3, the blurriness of some main features can be attributed to bones that affect the photoacoustic wave propagation path [41, 42], as well as sensitivity variations in the sensor. Irregularities in the sensor can be improved by using a sensor with better uniformity and higher Finesse; this is currently under development. In addition, a new sub-aperture correlation based numerical phase correction algorithm recently applied in interferometric full field imaging systems [43] is being implemented for our PAT reconstruction. Since this algorithm does not require a priori knowledge of any system parameters, we believe that substituting the optical wavefronts with the photoacoustic wave signals in this algorithm can greatly reduce the blurriness.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the benefits of combining PAM with OCT [23–28]. A comparison between Fig. 3(a) and Fig. 3(c) as well as between Fig. 6(c) and Fig. 6(e) further confirms the value of combining PAT with OCT. The different contrast mechanisms of photoacoustic imaging and OCT provide complementary information in the reconstructed image with photoacoustic image providing the distribution of absorbers and OCT image providing the background information based on the backscattering characteristics of different tissues. In addition to combining PAM and OCT, we believe the combination of a whole-body illumination PAT system with OCT [29] is also of great interest due to the deep penetration depth a PAT system can achieve. In [29], a 1050 nm SD-OCT system was combined with an optical detection PAT system. The scans for these two modalities were performed sequentially because a wedge was necessary to reduce the back-reflection of the OCT sample arm beam from the polymer film sensor. A scanner that enables co-registered PAT and swept source OCT (SS-OCT) scans is currently under development to enable simultaneous dual modality scanning.

5. Conclusion

This work demonstrates for the first time that optical detection spectroscopic PAT can non-invasively map E2-Crimson in 3D in transgenic zebrafish in vivo, establishing the value of E2-Crimson for PAT studies of transgenic models. The results of this work prelude the application of spectroscopic PAT for imaging E2-Crimson expressing zebrafish, which includes longitudinal 3D monitoring of inner organ dynamics as well as molecular and cellular changes that are associated with cancer formation and progression, tissue vascularization and regeneration. When considering the regenerative capacity of the zebrafish pancreas specifically, 3D imaging of a reporter protein will be especially interesting in the study of models of diseases such as pancreatitis.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Edward Zhang and Paul Beard at the University College London for their help in setting up the photoacoustic scanner. We also thank Wolfgang Driever at the University of Freiburg and Kenji Kohno at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology for providing the transparent mitfab692/b692/ednrb1b140/b140 fish line and the DTR probe. This work is supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project number: S10510-N20 and S10509-N20, the Medical University of Vienna, the European projects FAMOS (FP7 ICT 317744) and FUN OCT (FP7 HEALTH 201880).

References and links

- 1.Rice B. W., Contag C. H., “The importance of being red,” Nat. Biotechnol. 27(7), 624–625 (2009). 10.1038/nbt0709-624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtman J. W., Conchello J.-A., “Fluorescence microscopy,” Nat. Methods 2(12), 910–919 (2005). 10.1038/nmeth817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huisken J., Swoger J., Del Bene F., Wittbrodt J., Stelzer E. H. K., “Optical Sectioning Deep Inside Live Embryos by Selective Plane Illumination Microscopy,” Science 305(5686), 1007–1009 (2004). 10.1126/science.1100035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodt H. U., Leischner U., Schierloh A., Jährling N., Mauch C. P., Deininger K., Deussing J. M., Eder M., Zieglgänsberger W., Becker K., “Ultramicroscopy: three-dimensional visualization of neuronal networks in the whole mouse brain,” Nat. Methods 4(4), 331–336 (2007). 10.1038/nmeth1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharpe J., Ahlgren U., Perry P., Hill B., Ross A., Hecksher-Sørensen J., Baldock R., Davidson D., “Optical projection tomography as a tool for 3D microscopy and gene expression studies,” Science 296(5567), 541–545 (2002). 10.1126/science.1068206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGinty J., Taylor H. B., Chen L., Bugeon L., Lamb J. R., Dallman M. J., French P. M., “In vivo fluorescence lifetime optical projection tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(5), 1340–1350 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.001340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beard P., “Biomedical photoacoustic imaging,” Interface Focus 1(4), 602–631 (2011). 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.L. V. Wang and H.-i. Wu, Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging (Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken, N.J., 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang E., Beard P., “Broadband ultrasound field mapping system using a wavelength tuned, optically scanned focused laser beam to address a Fabry Perot polymer film sensor,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 53(7), 1330–1338 (2006). 10.1109/TUFFC.2006.1665081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang E., Laufer J., Beard P., “Backward-mode multiwavelength photoacoustic scanner using a planar Fabry-Perot polymer film ultrasound sensor for high-resolution three-dimensional imaging of biological tissues,” Appl. Opt. 47(4), 561–577 (2008). 10.1364/AO.47.000561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laufer J., Johnson P., Zhang E., Treeby B., Cox B., Pedley B., Beard P., “In vivo preclinical photoacoustic imaging of tumor vasculature development and therapy,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(5), 056016 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.056016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laufer J., Norris F., Cleary J., Zhang E., Treeby B., Cox B., Johnson P., Scambler P., Lythgoe M., Beard P., “In vivo photoacoustic imaging of mouse embryos,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(6), 061220 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.061220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox B., Laufer J. G., Arridge S. R., Beard P. C., “Quantitative spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging: a review,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(6), 061202 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.061202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fein M. R., Egeblad M., “Caught in the act: revealing the metastatic process by live imaging,” Dis. Model. Mech. 6(3), 580–593 (2013). 10.1242/dmm.009282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S., Leach S. D., “Screening pancreatic oncogenes in zebrafish using the Gal4/UAS system,” Methods Cell Biol. 105, 367–381 (2011). 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00015-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shive H. R., “Zebrafish Models for Human Cancer,” Vet. Pathol. 50(3), 468–482 (2013). 10.1177/0300985812467471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi W. Y., Poss K. D., “Cardiac regeneration,” Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 100, 319–344 (2012). 10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00010-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kizil C., Kaslin J., Kroehne V., Brand M., “Adult neurogenesis and brain regeneration in zebrafish,” Dev. Neurobiol. 72(3), 429–461 (2012). 10.1002/dneu.20918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss J. B., Koustubhan P., Greenman M., Parsons M. J., Walter I., Moss L. G., “Regeneration of the pancreas in adult zebrafish,” Diabetes 58(8), 1844–1851 (2009). 10.2337/db08-0628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Z., Jensen L. D., Rouhi P., Hosaka K., Länne T., Steffensen J. F., Wahlberg E., Cao Y., “Hypoxia-induced retinopathy model in adult zebrafish,” Nat. Protoc. 5(12), 1903–1910 (2010). 10.1038/nprot.2010.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye S., Yang R., Xiong J., Shung K. K., Zhou Q., Li C., Ren Q., “Label-free imaging of zebrafish larvae in vivo by photoacoustic microscopy,” Biomed. Opt. Express 3(2), 360–365 (2012). 10.1364/BOE.3.000360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma R., Distel M., Deán-Ben X. L., Ntziachristos V., Razansky D., “Non-invasive whole-body imaging of adult zebrafish with optoacoustic tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57(22), 7227–7237 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/22/7227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C., Han S., Kim S., Jeon M., Jeon M. Y., Kim C., Kim J., “Combined photoacoustic and optical coherence tomography using a single near-infrared supercontinuum laser source,” Appl. Opt. 52(9), 1824–1828 (2013). 10.1364/AO.52.001824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai X., Zhang Y., Li L., Choi S. W., MacEwan M. R., Yao J., Kim C., Xia Y., Wang L. V., “Investigation of neovascularization in three-dimensional porous scaffolds in vivo by a combination of multiscale photoacoustic microscopy and optical coherence tomography,” Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 19(3), 196–204 (2013). 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi L., Duan C., Xie H., Jiang H., “Miniature probe combining optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy and optical coherence tomography for in vivo microcirculation study,” Appl. Opt. 52(9), 1928–1931 (2013). 10.1364/AO.52.001928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X., Zhang H. F., Jiao S., “Optical coherence photoacoustic microscopy: accomplishing optical coherence tomography and photoacoustic microscopy with a single light source,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(3), 030502 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.3.030502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiao S., Xie Z., Zhang H. F., Puliafito C. A., “Simultaneous multimodal imaging with integrated photoacoustic microscopy and optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Lett. 34(19), 2961–2963 (2009). 10.1364/OL.34.002961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L., Maslov K., Ku G., Wang L. V., “Three-dimensional combined photoacoustic and optical coherence microscopy for in vivo microcirculation studies,” Opt. Express 17(19), 16450–16455 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.016450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang E. Z., Povazay B., Laufer J., Alex A., Hofer B., Pedley B., Glittenberg C., Treeby B., Cox B., Beard P., Drexler W., “Multimodal photoacoustic and optical coherence tomography scanner using an all optical detection scheme for 3D morphological skin imaging,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(8), 2202–2215 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.002202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alex A., Považay B., Hofer B., Popov S., Glittenberg C., Binder S., Drexler W., “Multispectral in vivo three-dimensional optical coherence tomography of human skin,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(2), 026025 (2010). 10.1117/1.3400665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alex A., Weingast J., Weinigel M., Kellner-Höfer M., Nemecek R., Binder M., Pehamberger H., König K., Drexler W., “Three-dimensional multiphoton/optical coherence tomography for diagnostic applications in dermatology,” J Biophotonics 6(4), 352–362 (2013). 10.1002/jbio.201200085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American National Standards Institute, “American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers,” ANSI Z136.1 2007–1 (2007).

- 33.Wan H., Korzh S., Li Z., Mudumana S. P., Korzh V., Jiang Y.-J., Lin S., Gong Z., “Analyses of pancreas development by generation of gfp transgenic zebrafish using an exocrine pancreas-specific elastaseA gene promoter,” Exp. Cell Res. 312(9), 1526–1539 (2006). 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furukawa N., Saito M., Hakoshima T., Kohno K., “A Diphtheria Toxin Receptor Deficient in Epidermal Growth Factor-Like Biological Activity,” J. Biochem. 140(6), 831–841 (2006). 10.1093/jb/mvj216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.M. Westerfield, The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). 4th ed. (Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laufer J., Jathoul A., Pule M., Beard P., “Evaluation of genetically expressed absorbing proteins using photoacoustic spectroscopy,” Proc. SPIE 8581, 85810X–, 85810X-6. (2013). 10.1117/12.2002497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treeby B. E., Cox B. T., “k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(2), 021314 (2010). 10.1117/1.3360308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Razansky D., Distel M., Vinegoni C., Ma R., Perrimon N., Köster R. W., Ntziachristos V., “Multispectral opto-acoustic tomography of deep-seated fluorescent proteins in vivo,” Nat. Photonics 3(7), 412–417 (2009). 10.1038/nphoton.2009.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filonov G. S., Krumholz A., Xia J., Yao J., Wang L. V., Verkhusha V. V., “Deep-Tissue Photoacoustic Tomography of a Genetically Encoded Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe,” Angew. Chem. 51(6), 1448–1451 (2012). 10.1002/anie.201107026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song K. H., Wang L. V., “Deep reflection-mode photoacoustic imaging of biological tissue,” J. Biomed. Opt. 12(6), 060503 (2007). 10.1117/1.2818045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang C., Nie L., Schoonover R. W., Guo Z., Schirra C. O., Anastasio M. A., Wang L. V., “Aberration correction for transcranial photoacoustic tomography of primates employing adjunct image data,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(6), 066016 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.066016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nie L., Cai X., Maslov K., Garcia-Uribe A., Anastasio M. A., Wang L. V., “Photoacoustic tomography through a whole adult human skull with a photon recycler,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(11), 110506 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.110506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar A., Drexler W., Leitgeb R. A., “Subaperture correlation based digital adaptive optics for full field optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Express 21(9), 10850–10866 (2013). 10.1364/OE.21.010850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]