Abstract

High-resolution microendoscopy (HRME) uses epi-fluorescence imaging with a coherent fiber-optic bundle to enable in vivo examination of cellular morphology. While the HRME platform has recently gained popularity as a simple alternative to confocal endomicroscopy, the axial response of HRME in thick, scattering tissue has yet to be described quantitatively. These details are important because when analyzing images collected by HRME, out-of-focus light may affect the accuracy of quantitative parameters such as nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio, which has been proposed as a diagnostic indicator of dysplasia or cancer. In this study we investigated the imaging properties of the HRME system by using phantoms simulating scattering tissue with fluorescently labeled nuclei. We directly compared HRME imaging with confocal endomicroscopy in phantoms and in vivo human tissue. HRME images defocused (deep) objects with apparent diameters and intensity levels that are in agreement with a simple geometric model. Out-of-focus nuclei contribute a relatively low, uniform background level to images which neither leads to the erroneous appearance of large nuclei from deep layers, nor prevents accurate imaging of superficial nuclei with high contrast.

OCIS codes: (060.0060) Fiber optics and optical communications, (110.0110) Imaging systems, (170.0170) Medical optics and biotechnology, (290.0290) Scattering

1. Introduction

Visual examination of tissue architecture at the cellular scale required for clinical diagnosis and staging of many types of cancer. Histopathology is by far the most commonly employed technique for examination of cellular morphology, but requires invasive biopsy collection, processing, and reading by an expert pathologist. Screening and surveillance requires the collection of a biopsy from any suspicious site; in some diseases such as Barrett’s esophagus, multiple biopsies are collected from the entire segment at risk [1]. This approach can result in a large number of unnecessary biopsies being collected, or in truly abnormal tissue being missed. The ability to view tissues with cellular-scale resolution in situ would allow directed collection of biopsies, possibly improving diagnostic yield and reducing cost.

Techniques such as confocal and multiphoton microscopy have shown feasibility of imaging with sub-cellular resolution in intact tissues, with fiber optic components providing access to sites within the body for microscopic imaging in situ [2]. Single fiber delivery systems require a compact scanning mechanism at the distal tip [3–7]. Alternatively, this miniaturization can be avoided by scanning the beam at the proximal end of a coherent fiber-optic bundle [8–10]. Both single fiber and bundle based endomicroscopy systems can also incorporate miniature focusing optics at the distal tip, either in a fixed position (which defines the axial location of the image plane), or with an axial translation mechanism to obtain optical sections at specific depths within the imaging range [2].

High-resolution microendoscopy (HRME) is a fiber-optic bundle based epi-fluorescence imaging modality which is capable of providing sub-cellular level resolution imaging in vivo. The simplicity, low cost, and real-time imaging performance of the HRME system have led to its use by several research groups in laboratory studies [11–24] and in vivo clinical investigations [25–28]. However, the imaging properties of the HRME system have not been fully characterized; in particular, the axial imaging range and sensitivity to out-of-focus light have to the best of our knowledge, not been quantitatively studied. The purpose of this paper is to quantitatively examine the imaging properties of the HRME system with regard to defocus in scattering media. This is important because unlike optical sectioning techniques, the HRME system possesses no inherent ability to reject out-of-focus light. When the distal tip of the fiber is placed on the tissue, fluorescence from both in-focus and defocused objects will be collected by the system. Out-of-focus light could in principle reduce the signal-to-background level and result in the appearance of defocused objects in the image, which may affect the accuracy of image analysis algorithms which quantify morphological features such as nuclear size, spacing, and nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio.

In this paper we have investigated the imaging performance of the HRME system both with and without the fiber bundle with regard to defocus, specifically as it relates to apparent particle size and intensity. We compare the imaging performance of HRME to a simple geometric model for a 2-D phantom, we quantify the effect of defocus (object depth) on apparent image feature size in 3-D phantoms with varying scattering coefficients, and we compare the imaging properties of HRME directly to those of confocal endomicroscopy in biological tissue in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 HRME system

Assembly of the HRME system has been described in detail elsewhere [18]. Light from a 455 nm LED (Thorlabs M455L2), is collected by a condenser lens (Olympus Plan N 4x objective), passed through a 430-475 nm bandpass excitation filter (Semrock), reflected at a 485 nm edge dichroic beamsplitter (Chroma), to an infinity-corrected objective lens (Olympus Plan N 10x). A silica fiber-optic bundle (Sumitomo, IGN-08/30) with 720 μm imaging diameter, comprising 30,000 individual fibers each 2.1 μm in diameter with NA 0.35 is positioned with its proximal end face at the objective’s working distance (Fig. 1(a) ).

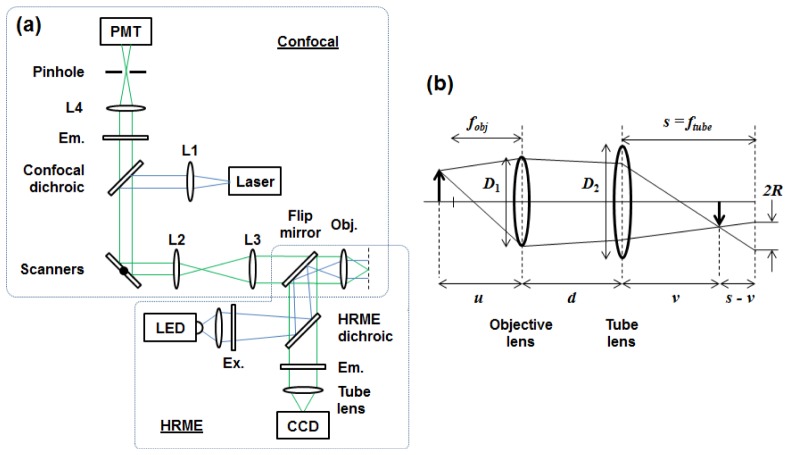

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the optical setup. For microendoscopy, one end of a fiber-optic bundle is placed at the working distance of the objective lens. (a) Confocal and HRME beam paths are combined with a flip mirror. L1-4: lenses, Ex: excitation filter, Em: emission filter, Obj: Objective lens. (b) Ray diagram for the geometric model used to examine HRME imaging with defocus. An object located at distance u from the objective lens (defocus of u – fobj) will form a focused image at v, and a blurred image of radius R on the camera at s = ftube. The objective lens and tube lens have diameters D 1 and D 2 respectively, and are separated by distance d.

At the distal end of the fiber, excitation light generates fluorescence from a labeled sample. With the LED at full power, the illumination intensity was measured to be 1.13 mW/mm2 at the proximal end of the fiber and 1.03 mW/mm2 at the distal end. Fluorescent light is collected by the fiber bundle and relayed back through the objective lens, through the dichroic mirror and 506-594 nm bandpass emission filter (Semrock), and a 150 mm focal length tube lens (Thorlabs) which images the fluorescent emission onto a CCD sensor (Point Grey Research, Grasshopper 2).

2.2 Confocal microendoscope system

A point-scanning confocal microendoscope system was assembled (Fig. 1(a)), using a 488 nm fiber-coupled laser (Blue Sky Research) for fluorescence excitation. A dichroic mirror with 488 nm edge (Semrock) and lenses L1-3 (focal lengths 35 mm, 50 mm, and 100 mm, respectively) form a collimated excitation beam, pivoting at the back aperture of the same shared 10x / 0.25 objective lens used by the HRME system. In the detection arm, fluorescence is transmitted by a separate emission filter with the same 506-594 nm bandpass range as in the HRME, focused by a 50 mm focal length lens (L4) through a 25 μm pinhole, and collected by a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu). The axial resolution of the confocal microendoscope was measured by removing the emission filter and recording the signal intensity as a mirror was translated away from the bundle’s distal face in 1 μm increments. The distance at which the intensity dropped to half the value at contact was 6 μm. Imaging with the confocal microendoscope was performed with the fiber bundle’s distal tip placed directly in contact with the sample; no additional optics were used. To enable direct comparison between images acquired with the HRME and the confocal microendoscope, the systems were coupled together with a flip mirror positioned immediately behind the objective lens to enable rapid selection of either imaging mode without repositioning the sample.

2.3 Geometric model

We developed a simple geometric model to predict the effect of defocus on an object’s apparent size and intensity as measured by the HRME system (Fig. 1(b)). The purpose of this model was to allow for comparison with experimental data, and was not an attempt to predict object depth in HRME images. This analysis was based on a model from the literature which derived an expression for the blur spot radius (R) as a function of CCD camera position (s) for a fixed object (u) [29]. For the HRME system, the CCD camera is instead considered fixed at the focal plane of the tube lens (s = f tube) and object position u is variable (u – fobj equals defocus). v is the distance from the tube lens to the image plane. Using similar triangles in Fig. 1(b) and the Gaussian equation for a two lens system for v, we obtain:

| (1) |

In this model, R is the radius of the blurred image of a point object, formed at the camera plane. To obtain the apparent physical radius of the object (AR), we divide R by the system magnification, M = ftube / fobj :

| (2) |

The image formed from an extended object is the image of a point object (Eq. (2)) convolved with the object function, which for the experiments conducted here is a spherical fluorescent bead of 14.8 μm diameter. Due to the convolution of the blur radius with the extended object, the apparent radius of the object is equal to the sum of the object’s radius and the blur radius. The apparent diameter, AD is twice that value, where r is the radius of the object:

| (3) |

Since the total amount of light imaged onto the camera from each object is essentially constant for small amounts of defocus, we can express the light flux, F, from each object as:

| (4) |

where Ī0 is the mean intensity of the focused particle, A0 is the area of the focused particle, Īblur is the mean intensity of the blurred image, Ablur is the area of the blurred image:

| (5) |

Equations (3) and (5) are used to model the apparent diameter and intensity of defocused objects in this paper.

2.4 Optical phantoms

A 2-D monolayer of 14.8 μm diameter green fluorescent beads (Life Technologies, F-21010) was prepared by applying 5 μL of beads in suspension to a microscope slide and allowing the droplet to dry. The slide was mounted on a motorized translation stage (Newport MFA-CC, on-axis accuracy ± 4 μm), and images were collected with the slide located at discrete positions (u in Fig. 1(b)) between −200 μm and + 200 μm relative to the objective’s focal plane (the fiber bundle was not used at this stage). Images were collected with the camera’s proprietary software (FlyCap2, Point Grey Research, Firmware version 1.6.3.0); the gain was fixed at 0 dB and the exposure time was 6.59 ms. Each image was then analyzed in ImageJ (NIH version 1.46r), with each bead defined as a region-of-interest by manual segmentation using the circle tool. The diameter and mean intensity of each ROI was then calculated by analysis within ImageJ, following subtraction of the background (dark) level for each image.

Three-dimensional phantoms were made with 14.8 μm diameter green fluorescent beads dispersed within non-scattering (NS), low-scattering (LS), and high-scattering (HS) phantoms. We used an intralipid-agar phantom system which has previously been used to simulate biological tissue [30–32]. 0.1 g of agar (Sigma, A9799) and 0.2 g of fluorescent beads in solution were mixed with varying amounts of DI water; 10.0 mL for the NS phantom, 9.75 mL for the LS phantom, 9.0 mL for the HS phantom. Each mixture was vortexed until the agar was dispersed, then immersed into boiling water for 10 minutes. 20% Intralipid (Sigma, I141) was then added to the fluorescent bead mixture in varying quantities; no Intralipid was added to the NS phantom, 0.25 mL was added to the LS sample, 1 mL to the HS sample (NS = 0%, LS = 0.5%, HS = 2.0% Intralipid solids). The mixture was then vortexed again, poured into a 60 mm diameter petri dish and allowed to cool to room temperature overnight. We used a spatial frequency domain imaging system [33] to measure the reduced scattering coefficients of the phantoms containing Intralipid, obtaining values of 1.08 mm−1 and 2.54 mm−1 for the low and high scattering phantoms, respectively, at a wavelength of 520 nm.

2.5 Three-dimensional imaging

The agar phantoms were mounted on the same motorized stage as used for the 2-D phantoms and translated such that a focused image of the phantom surface was seen on the HRME camera. This location was then considered to be depth z = 0 for the phantom under study. Images were then collected as the phantom was moved toward the objective lens in 10 μm steps, with fluorescent beads at different depths moving through the focal plane. Several axial scans at different lateral regions were collected, allowing us to obtain image data from beads located at a range of depths within each phantom. Images were collected at 0 dB gain and exposure times of 5.00 ms, 6.00 ms, and 3.00 ms, respectively, for the NS, LS, and HS samples.

2.6 Fiber-optic imaging

For imaging with the complete HRME system, the fiber bundle was placed in the system with its proximal end at the working distance of the objective lens. The distal end of the bundle was brought into gentle contact with the surface of the agar phantoms and images were acquired at several different lateral regions on the phantom surface. Each of these regions was then imaged without the fiber bundle, with images taken over an axial scan range as described in section 2.5. The same field-of-view in the sample was located by placing an ink mark on the sample surface adjacent to the fiber bundle tip, to guide us to the same region when the fiber bundle was removed. We then identified the exact same region by carefully searching visually for the same distribution of fluorescent beads. This process allowed us to determine the depth of each fluorescent bead in the fiber-optic bundle images without physically advancing the bundle into the phantom. Fiber-optic HRME images were taken with 0 dB camera gain and 15.00 ms exposure. The non-fiber-optic images were taken at the same exposure settings as described in section 2.5; 5.00 ms, 6.00 ms, and 3.00 ms, respectively, for the NS, LS, and HS samples.

2.7 In-vivo imaging

Images of normal human oral mucosa were acquired with the HRME and confocal microendoscope, following topical application of proflavine solution (0.01% w/v in sterile PBS). Images with each system were recorded in quick succession by use of the flip mirror (Fig. 1(a)). Human subject imaging was performed under a protocol approved by the Rutgers University IRB.

3. Results

3.1 Epi-fluorescence imaging of phantoms

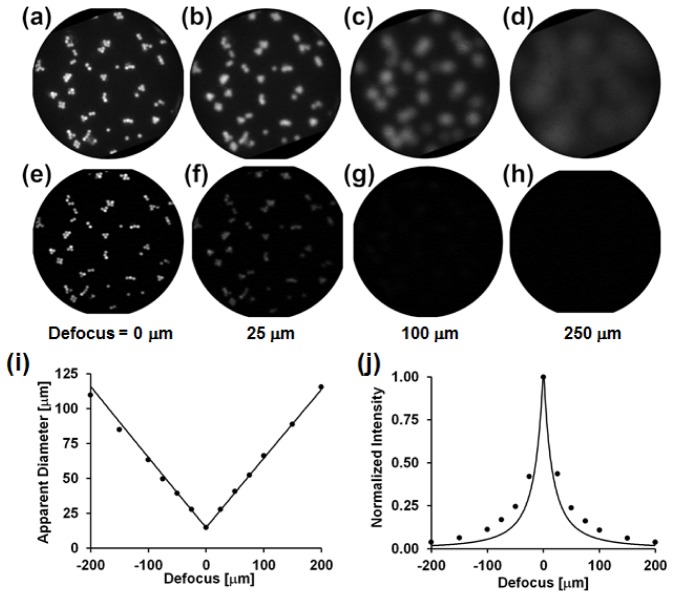

Figure 2 shows images of a 2-D monolayer of fluorescent beads imaged with the HRME (panels a-d) and the confocal microendoscope (panels e-h), as a function of defocus. It can be seen that with HRME, the apparent diameter of the beads increases, and mean intensity rapidly decreases with defocus, leading to nearly uniform background intensity for defocus greater than approximately 250 μm. With confocal microendoscopy, as expected, the intensity of out-of-focus beads is rapidly attenuated, preventing significant elevation of background arising from defocused objects.

Fig. 2.

HRME (a-d) and confocal microendoscopy (e-h) imaging of a monolayer of 14.8 μm diameter beads as a function of defocus (distance from the monolayer to the fiber bundle’s distal tip). All images are 720 μm in diameter. (i) Measured (dots) and theoretical prediction (line) for bead diameter as a function of defocus. (j) Measured (dots) and theoretical prediction (line) for the mean bead intensity as a function of defocus.

Figures 2(i) and 2(j) quantify the apparent diameter and mean intensity, respectively, of 14.8 μm fluorescent beads as a function of defocus when imaged with HRME, alongside the theoretical predictions from the geometric model described in section 2.3. Good agreement between the measured bead diameters and predicted values supports our use of manual delineation of beads.

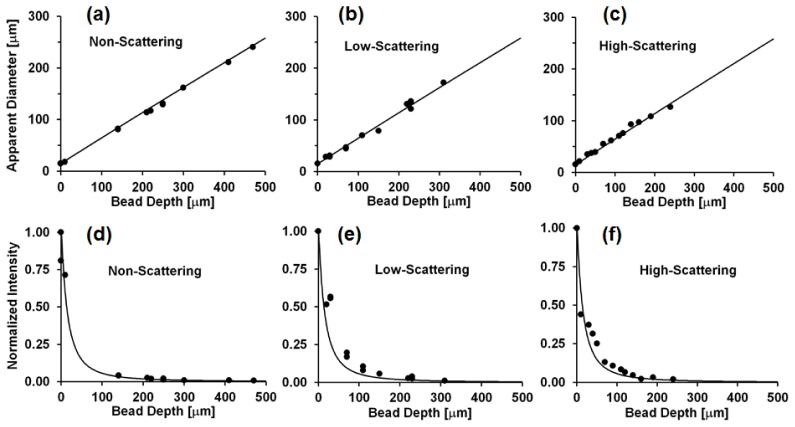

Figure 3 shows the apparent diameter and mean intensity of fluorescent beads as a function of bead depth within thick 3-D phantoms. These images were acquired without the fiber bundle, with the surface of the phantom positioned at the working distance of the HRME objective lens; “bead depth” is thus equivalent to defocus. These results maintain good agreement with predictions from the geometric model under all three levels of scattering tested, even though the model neglects the effects of scattering. Here, the reduced scattering coefficients are on the order of cm−1, whereas defocus reduces the imaged mean object intensity significantly over distances on the order of tens of micrometers. A 50% reduction in mean intensity occurs with defocus of approximately 5 μm and a 90% reduction in mean intensity after approximately 25 μm (Fig. 3(d)-3(f)). While it appears that higher levels of scattering reduce the maximum achievable imaging depth (NS ~500 μm, LS ~300 μm, HS ~250 μm), the effect of scattering at levels simulating biological tissue appears small compared to the effect of defocus; the predicted mean intensity of a bead located at a depth (defocus) of 240 μm is only ~1% of that of a bead located at the surface (in focus).

Fig. 3.

(a,b,c) Apparent diameter of 14.8 μm fluorescent beads in NS, LS, and HS phantoms as a function of bead depth beneath the phantom surface. (d,e,f) Normalized mean intensity of imaged fluorescent beads as a function of depth beneath the phantom surface in NS, LS, and HS samples. Circles: experimental data, line: predicted values from model.

3.2 Fiber-optic HRME imaging of 3-D phantoms

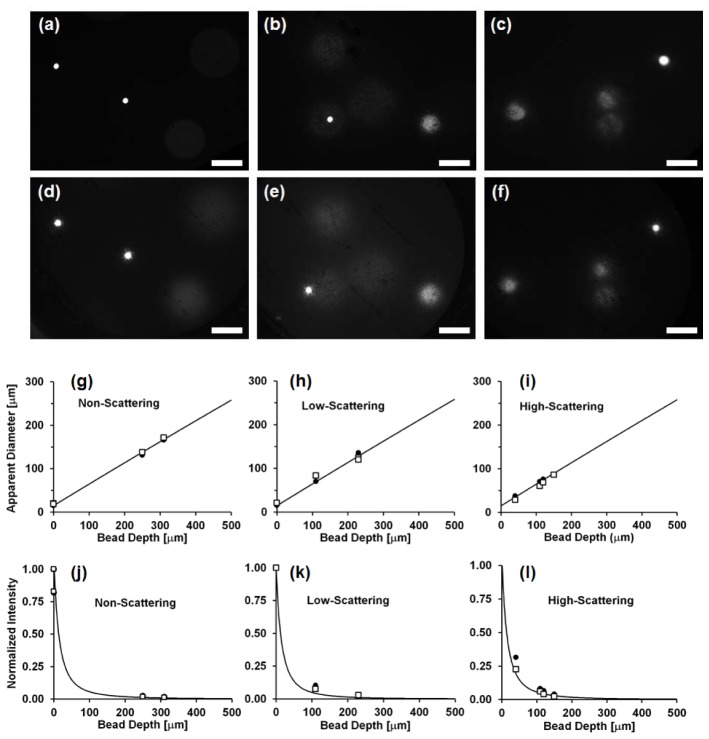

Figure 4 presents a side-by-side comparison of 3-D phantom imaging with the HRME, both without (Fig. 4(a)-4(c)) and with the fiber-optic bundle (Fig. 4(d)-4(f)). All images have been brightened by the same amount in order to make the dimmer beads more apparent. Figure 4(g)-4(i) shows the apparent diameter of the beads in the HRME images as a function of bead depth within the 3-D phantom. Figure 4(j)-4(l) shows the normalized mean intensity of the beads in the HRME images as a function of bead depth. These data suggest that the HRME fiber-bundle based system displays similar imaging performance with respect to the effect of defocus, to the epi-fluorescence microscope; the fiber bundle confers no sectioning ability.

Fig. 4.

(a-f) Comparison between images of 3-D phantoms taken without (a-c) and with the fiber bundle (d-f) in NS (a,d), LS (b,e), and HS (c,f) samples. Scale bar = 100 μm. (g-i) Apparent diameter at surface of 14.8 μm fluorescent beads in NS, LS, and HS phantoms. (j-l) Normalized intensity at phantom surface in NS, LS, and HS samples. (Squares: data from fiber optic images, circles: data from non-fiber-optic images, solid line: expected values from model).

3.3 Comparison of HRME and confocal microendoscopy

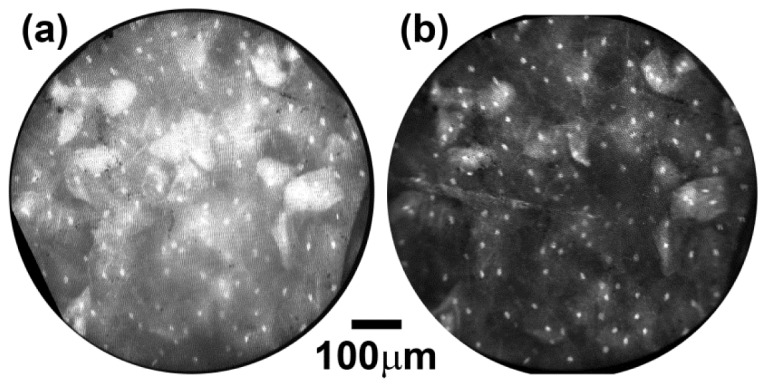

Figure 5 shows images of in vivo human oral mucosa taken using the HRME system (Fig. 5(a)) and confocal microendoscopy (Fig. 5(b)). These images were acquired nearly simultaneously, with the only delay arising from activating the flip mirror which allowed us to switch between systems (Fig. 1(a)). Following staining with topical proflavine (0.01% w/v), cell nuclei appear as discrete bright dots within each image. The confocal image (b) appears to exhibit lower background and higher contrast which allows nuclei to be identified more easily in regions which have more crowded or overlying cells. However, the HRME still retains the ability to resolve nuclear detail in most parts of the image, without being adversely affected by defocused objects.

Fig. 5.

In vivo imaging of human oral mucosa with HRME (a) and confocal microendoscope systems (b).

4. Discussion & conclusions

We quantitatively examined the axial response of a recently developed high-resolution microendoscope (HRME) system in a series of optical phantoms. Phantoms were designed to simulate fluorescently labeled nuclei distributed at varying depths within scattering tissue, mimicking the proflavine-stained epithelium imaged in earlier HRME studies. The HRME has no optical sectioning ability with which to eliminate out-of-focus light when imaging thick tissue, but nevertheless can clearly delineate epithelial nuclei in normal and neoplastic tissues [26–28]. We showed here that the HRME system produces images of deep lying (defocused) objects with apparent diameters as predicted by a simple geometric model. This could in principle lead to the apparent size of deep nuclei being mistakenly overestimated by morphologic analysis algorithms. However, the average intensity of defocused objects was also shown to rapidly decrease with defocus within a few 100 μm. In a scattering matrix, the intensity of defocused objects attenuated even more rapidly, resulting in a non-zero background level contributing to HRME images, but not sufficient to reduce contrast of the most superficial nuclei.

Confocal endomicroscopy appears to provide higher contrast than HRME when nuclei are particularly crowded, and can offer the ability to examine tissue across the full thickness of the epithelium. Use of fluorescent contrast agents such as fluorescein and indocyanine green which distribute non-specifically throughout tissue would also benefit from the ability of confocal methods to prevent out-of-focus light from reaching the detector and lowering contrast. Interestingly, our findings appear complementary to those of El Hallani et al., who recently demonstrated that independent of imaging system, limited diffusion of the proflavine contrast agent restricts imaging to depths of only 50-100 μm in epithelial tissues [34]. Thus it would appear that the effects of defocus shown here, in addition to the biodistribution of contrast agent, both enable HRME to effectively resolve cell nuclei within only the most superficial layers of the epithelium with minimal effect from out of focus light. Previous and future studies which quantify nuclear morphology for tissue classification [16, 26–28], should not be adversely affected by fluorescence from nuclei located deeper within the epithelium.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge helpful discussions on confocal microscopy with Noah Bedard, PhD.

References and links

- 1.Wang K. K., Sampliner R. E., Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology , “Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus,” Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103(3), 788–797 (2008). 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goetz M., Kiesslich R., “Advances of endomicroscopy for gastrointestinal physiology and diseases,” Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 298(6), G797–G806 (2010). 10.1152/ajpgi.00027.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polglase A. L., McLaren W. J., Skinner S. A., Kiesslich R., Neurath M. F., Delaney P. M., “A fluorescence confocal endomicroscope for in vivo microscopy of the upper- and the lower-GI tract,” Gastrointest. Endosc. 62(5), 686–695 (2005). 10.1016/j.gie.2005.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thong P. S.-P., Olivo M., Kho K.-W., Zheng W., Mancer K., Harris M., Soo K.-C., “Laser confocal endomicroscopy as a novel technique for fluorescence diagnostic imaging of the oral cavity,” J. Biomed. Opt. 12(1), 014007 (2007). 10.1117/1.2710193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astner S., Dietterle S., Otberg N., Röwert-Huber H.-J., Stockfleth E., Lademann J., “Clinical applicability of in vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for noninvasive diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of nonmelanoma skin cancer,” J. Biomed. Opt. 13(1), 014003 (2008). 10.1117/1.2837411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan J., Quinn M. A., Pyman J. M., Delaney P. M., McLaren W. J., “Detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in vivo using confocal endomicroscopy,” BJOG 116(12), 1663–1670 (2009). 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunbar K. B., Okolo P., 3rd, Montgomery E., Canto M. I., “Confocal laser endomicroscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and endoscopically inapparent Barrett’s neoplasia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled, crossover trial,” Gastrointest. Endosc. 70(4), 645–654 (2009). 10.1016/j.gie.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace M. B., Sharma P., Lightdale C., Wolfsen H., Coron E., Buchner A., Bajbouj M., Bansal A., Rastogi A., Abrams J., Crook J. E., Meining A., “Preliminary accuracy and interobserver agreement for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus with probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy,” Gastrointest. Endosc. 72(1), 19–24 (2010). 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane P. M., Lam S., McWilliams A., Leriche J. C., Anderson M. W., Macaulay C. E., “Confocal fluorescence microendoscopy of bronchial epithelium,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(2), 024008 (2009). 10.1117/1.3103583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A. A. Tanbakuchi, J. A. Udovich, A. R. Rouse, K. D. Hatch, A. F. Gmitro, “In vivo imaging of ovarian tissue using a novel confocal microlaparoscope,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 202, 90.e1–9 (2010). 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dromard T., Ravaine V., Ravaine S., Lévêque J.-L., Sojic N., “Remote in vivo imaging of human skin corneocytes by means of an optical fiber bundle,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78(5), 053709 (2007). 10.1063/1.2736346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muldoon T. J., Pierce M. C., Nida D. L., Williams M. D., Gillenwater A., Richards-Kortum R., “Subcellular-resolution molecular imaging within living tissue by fiber microendoscopy,” Opt. Express 15(25), 16413–16423 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.016413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muldoon T. J., Anandasabapathy S., Maru D., Richards-Kortum R., “High-resolution imaging in Barrett’s esophagus: a novel, low-cost endoscopic microscope,” Gastrointest. Endosc. 68(4), 737–744 (2008). 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong W., Celli J. P., Rizvi I., Mai Z., Spring B. Q., Yun S. H., Hasan T., “ In vivo high-resolution fluorescence microendoscopy for ovarian cancer detection and treatment monitoring,” Br. J. Cancer 101(12), 2015–2022 (2009). 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosbach K. J., Shin D., Muldoon T. J., Quraishi M. A., Middleton L. P., Hunt K. K., Meric-Bernstam F., Yu T.-K., Richards-Kortum R. R., Yang W., “High-resolution fiber optic microscopy with fluorescent contrast enhancement for the identification of axillary lymph node metastases in breast cancer: a pilot study,” Biomed. Opt. Express 1(3), 911–922 (2010). 10.1364/BOE.1.000911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muldoon T. J., Roblyer D., Williams M. D., Stepanek V. M. T., Richards-Kortum R., Gillenwater A. M., “Noninvasive imaging of oral neoplasia with a high-resolution fiber-optic microendoscope,” Head Neck 34(3), 305–312 (2012). 10.1002/hed.21735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elahi S. F., Miller S. J., Joshi B., Wang T. D., “Targeted imaging of colorectal dysplasia in living mice with fluorescence microendoscopy,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(4), 981–986 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.000981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.M. C. Pierce, D. Yu, and R. Richards-Kortum, “High-resolution fiber-optic microendoscopy for in situ cellular imaging,” JOVE 47; http://www.jove.com/index/Details.stp?ID=2306 (2011). 10.3791/2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mufti N., Kong Y., Cirillo J. D., Maitland K. C., “Fiber optic microendoscopy for preclinical study of bacterial infection dynamics,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(5), 1121–1134 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.001121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regunathan R., Woo J., Pierce M. C., Polydorides A. D., Raoufi M., Roayaie S., Schwartz M., Labow D., Shin D., Suzuki R., Bhutani M. S., Coghlan L. G., Richards-Kortum R., Anandasabapathy S., Kim M. K., “Feasibility and preliminary accuracy of high-resolution imaging of the liver and pancreas using FNA compatible microendoscopy (with video),” Gastrointest. Endosc. 76(2), 293–300 (2012). 10.1016/j.gie.2012.04.445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila P. M., Park C. W., Pierce M. C., Goldstein G. H., Levy L., Gurudutt V. V., Polydorides A. D., Godbold J. H., Teng M. S., Genden E. M., Miles B. A., Anandasabapathy S., Gillenwater A. M., Richards-Kortum R., Sikora A. G., “Discrimination of benign and neoplastic mucosa with a high-resolution microendoscope (HRME) in head and neck cancer,” Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19(11), 3534–3539 (2012). 10.1245/s10434-012-2351-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Göbel W., Brucker D., Kienast Y., Johansson A., Kniebühler G., Rühm A., Eigenbrod S., Fischer S., Goetz M., Kreth F.-W., Ehrhardt A., Stepp H., Irion K.-M., Herms J., “Optical needle endoscope for safe and precise stereotactically guided biopsy sampling in neurosurgery,” Opt. Express 20(24), 26117–26126 (2012). 10.1364/OE.20.026117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao P., Shi W., Hajireza P., Zemp R. J., “Integrated micro-endoscopy system for simultaneous fluorescence and optical-resolution photoacoustic imaging,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(7), 076024 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.7.076024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall R. A., Barton J. K., “Fluorescence-based surface magnifying chromoendoscopy and optical coherence tomography endoscope,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(8), 086003 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.8.086003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce M. C., Vila P. M., Polydorides A. D., Richards-Kortum R., Anandasabapathy S., “Low-cost endomicroscopy in the esophagus and colon,” Am. J. Gastroenterol. 106(9), 1722–1724 (2011). 10.1038/ajg.2011.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierce M. C., Schwarz R. A., Bhattar V. S., Mondrik S., Williams M. D., Lee J. J., Richards-Kortum R., Gillenwater A. M., “Accuracy of in vivo multimodal optical imaging for detection of oral neoplasia,” Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 5(6), 801–809 (2012). 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn M. K., Bubi T. C., Pierce M. C., Kayembe M. K., Ramogola-Masire D., Richards-Kortum R., “High-resolution microendoscopy for the detection of cervical neoplasia in low-resource settings,” PLoS ONE 7(9), e44924 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0044924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierce M. C., Guan Y. Y., Quinn M. K., Zhang X., Zhang W.-H., Qiao Y.-L., Castle P., Richards-Kortum R., “A pilot study of low-cost, high-resolution microendoscopy as a tool for identifying women with cervical precancer,” Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 5(11), 1273–1279 (2012). 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subbarao M., Surya G., “Depth from defocus: A spatial domain approach,” Int. J. Comput. Vis. 13(3), 271–294 (1994). 10.1007/BF02028349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaudhari A. J., Darvas F., Bading J. R., Moats R. A., Conti P. S., Smith D. J., Cherry S. R., Leahy R. M., “Hyperspectral and multispectral bioluminescence optical tomography for small animal imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol. 50(23), 5421–5441 (2005). 10.1088/0031-9155/50/23/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garofalakis A., Zacharakis G., Filippidis G., Sanidas E., Tsiftsis D. D., Ntziachristos V., Papazoglou T. G., Ripoll J., “Characterization of the reduced scattering coefficient for optically thin samples: theory and experiments,” J. Opt. A, Pure Appl. Opt. 6(7), 725–735 (2004). 10.1088/1464-4258/6/7/012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cubeddu R., Pifferi A., Taroni P., Torricelli A., Valentini G., “A solid tissue phantom for photon migration studies,” Phys. Med. Biol. 42(10), 1971–1979 (1997). 10.1088/0031-9155/42/10/011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuccia D. J., Bevilacqua F., Durkin A. J., Ayers F. R., Tromberg B. J., “Quantitation and mapping of tissue optical properties using modulated imaging,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(2), 024012 (2009). 10.1117/1.3088140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Hallani S., Poh C. F., Macaulay C. E., Follen M., Guillaud M., Lane P., “ Ex vivo confocal imaging with contrast agents for the detection of oral potentially malignant lesions,” Oral Oncol. 49(6), 582–590 (2013). 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]