Abstract

Involvement in creating anti-alcohol advertisements generates enthusiasm among adolescents, however, little is known about the messages adolescents develop for these activities. In this paper, we present a content analysis of 72 print alcohol counter-advertisements created by high school (age 14–17 years old) and college (18–25 years old) students. The posters were content analyzed for poster message content, persuasion strategies, and production components, and we compared high school and college student posters. All of the posters used a slogan to highlight the main point/message of the ad and counter-arguments/consequences to support the slogans. The most frequently depicted consequences were negative consequences of alcohol use followed by negative-positive consequence comparison. Persuasion strategies were sparingly used in advertisements and included having fun/one of the gang, humor/unexpected, glamour/sex appeal, and endorsement. Finally, posters displayed a number of production techniques including depicting people, clear setting, multiple colors, different font sizes, and object placement. College and high school student constructed posters were similar on many features (for instance, posters displayed similar frequency of utilization of slogans, negative consequences and positive-negative consequence comparisons), but were different on the use of positive consequences of not using alcohol and before-after comparisons. Implications for teaching media literacy and involving adolescents and youth in developing alcohol prevention messages are discussed.

Advertising promoting alcohol consumption forms a pervasive presence in the lives of adolescents. Companies spent more than $8.2 billion from 2001–2009 placing 2,664,919 alcohol product advertisements on U.S. television from 2001–2009 (Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth [CAMY], 2010). Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on U.S. television increased by 71% over the same time period (CAMY, 2010). Longitudinal studies consistently indicate that exposure to alcohol advertising and promotion raises the likelihood that adolescents will initiate alcohol use and/or increase their consumption (e.g., Anderson, de Bruijn, Angus, Gordon, & Hastings, 2009; Smith & Foxcroft, 2009;Snyder, Milici, Slater, Sun, & Strizhakova, 2006). The high rate of adolescent exposure to alcohol advertising and promotion (King et al., 2009), along with their susceptibility to advertising-associated drinking (Anderson et al., 2009), makes it imperative to counter the potential effects of advertising on young people.

One approach to countering the potential effects of alcohol advertising on adolescents is to help them critically understand and develop prevention messages through an age-appropriate intervention. The Committee on Communications at the American Academy of Pediatrics (2006) stressed the buffering role of media education in reducing the negative influence of alcohol advertising on children and adolescents. Empirical evidence from media literacy intervention research appears quite promising in this respect (e.g., Banerjee & Greene 2006, 2007; Kupersmidt, Scull, & Austin, 2010; Pinkleton, Austin, Cohen, Miller, & Fitzgerald, 2007). Media literacy advocates a critical analysis of various kinds of mass media messages, identification of the functions of the media, and engagement that encourages students to critically and consciously examine media messages (Considine & Haley, 1992). In addition, media literacy encourages an understanding of the construction of media messages and how interactions among various production techniques produce specific effects (Kubey, 2005; Tyner, 1992). The Youth Message Development (YMD) curriculum incorporates these principles in a media literacy intervention to reduce underage drinking in high school students. We also piloted the curriculum with college students, so there is potential to adapt it to a more mature audience, but the feasibility testing focused on high school students. During the poster planning portion of this intervention, students utilize the critical analysis and media message construction skills they learned to actively create their own alcohol counter-advertisements. By creating counter-advertisements, adolescents apply media literacy skills to communicate positive health messages in a fun and engaging exercise (Collins, Doyon, McAuley & Quijada, 2011). This paper focuses on a content analysis of counter-advertisements created in a pilot test of YMD, in order to assess common health message content and provide recommendations on how to modify the curriculum so that students develop more effective (or media-literacy informed) content and messages for potential distribution.

Counter-advertising can be defined as messages that take “a position contrary to an advertising message that preceded it. Such advertising may be used to take an opposing position on a controversial topic, or to counter an impression that might be made by another’s advertising” (Litwin, 2008, p. 116). Counter-advertising, however, can also be viewed as messages promoting alternatives such as choosing not to smoke. Students participating in a media literacy curriculum apply this definition to alcohol counter-advertising by critically examining pro-alcohol advertisements and then applying persuasion techniques used by those advertisements to deliver counter-claim messages and factual information about the impact of alcohol missing from alcohol advertisements.

Research examining the effectiveness of alcohol counter-advertising suggests that counter-advertising may reduce youth pro-alcohol attitudes, perceptions, and intentions (e.g., Agostinelli & Grube, 2002; Austin, Pinkelton, & Fujioka, 1999; Saffer, 2002), but direct effects on alcohol misuse need more rigorous evaluation. Additional evidence on the effectiveness of counter-advertising comes from the tobacco literature (e.g., Agostinelli & Grube, 2003; Apollonio & Malone, 2009; DeJong & Hoffman, 2000; Lee & Cheng, 2010; MacKenzie, Johnson, Chapman, & Holding, 2009) and concludes that overall, counter-advertising pro-tobacco messages in the form of public service announcements (PSAs) reduces tobacco use (see Banerjee & Greene, 2006). In a review addressing effects of alcohol advertising, Saffer (2002) heralds counter-advertising as a significant public health practice with broader implications and adds, “These findings indicate that increased counter-advertising, rather than new advertising bans, appears to be the better choice for public policy” (p. 173).

Whereas counter-advertising itself seems a promising strategy for reducing youth alcohol use, current research also indicates that involving youth in prevention efforts or campaigns increases message acceptance and engagement with the campaign (e.g., Farrelly, Davis, Haviland, Messeri, & Healton, 2005). Two separate but related theoretical approaches help support the role of youth generated counter-advertising for mitigating youth alcohol use. First, a social cognitive theory-based approach posits that perspective taking moves an intervention beyond simply imparting knowledge and skills to also activate motivation and better influence cognitions and subsequent behavior (see Greene, current issue). Media literacy provides adolescents with tools and skills needed to resist advertising, while developing their own counter-advertisements encourages them to take the perspective of other adolescents and utilize perspective taking in message planning (see Banerjee & Greene, 2006, 2007; Greene et al., 2011). This social-cognitive based approach is articulated more fully in the theory of active involvement (TAI, Greene, current issue). TAI focuses on how perspective-taking and message planning activities actively involve adolescents, motivate their engagement, and initiate a process that leads to change.

Second, the cultural grounding approach employed by Hecht and colleagues in developing the “keepin’ it REAL” prevention curriculum (e.g., Harthun, Dustman, Reeves, Hecht, & Marsiglia, 2009; Hecht & Krieger, 2006; Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009) helps explain why youth involvement may play a key role in the acceptance of counter-advertisements. Cultural grounding refers to the development of prevention messages so that they reflect the cultures and lives of adolescents, often by having the adolescent targets of the messages participate in creating them. From this perspective, adolescents better relate to particular messages through seeing representations of themselves, their families, and their communities in the values, activities, settings, clothing, language, etc. depicted in the messages (Hecht, Marsiglia, & Kayo, 2004; see Miller-Day & Hecht, current issue). Therefore, prevention messages that are developed with youth involvement may not only resonate well with other youth but may also be better remembered and understood (see Lee, Hecht, Miller-Day, & Elek, 2011).

Agostinelli and Grube (2002) note that government agencies, community action groups, and industry sponsors produce most of the alcohol counter-advertising messages. Involvement of youth in these counter-advertising efforts, to date, is limited. Research indicates that adolescents and adults have different perceptions of PSAs, for example differing in ratings of interest, believability, understandability and perceived effectiveness (Solomon, Hendry, Kalynych, Taylor, & Tepas, 2010). Most studies evaluating PSA-based mass media campaigns have consistently reported little or no effects, often through failure to attract attention or be remembered (e.g., Grube & Wallack, 1994; Snyder & Hamilton, 2002). In contrast, youth produced messages have been found to be highly engaging (Lee et al., 2011) and effective (Warren et al., 2006) in school-based drug prevention curriculum. Therefore, instead of having adults create underage alcohol prevention messages, involving youth in creating alcohol counter-advertising messages may help produce messages that resonate well with adolescents with the ultimate goal of increased effectiveness (in this case reduced alcohol initiation and use).

One noteworthy campaign exception, the national “Truth” campaign, involved youth for inspiration, guidance, and feedback (Hicks, 2001) and targeted 12 to 17 year olds primarily through tobacco counter-marketing messages (Farrelly et al., 2005). Other school-based substance use prevention programs have involved youth in creating anti-substance use messages (e.g., Banerjee & Greene, 2006, 2007,2012; Gosin, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2003; Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009; Kreiger et al., current issue; Pinkleton et al., 2007), but few have analyzed the content or effectiveness of these messages created by adolescents (for an exception, see Banerjee & Greene, 2012).

This paper presents a content analysis of print alcohol counter-advertisements created by adolescents as part of the YMD training. The analysis is guided by the theoretically- and research-informed content of the curriculum. Although there are no set guidelines for how to develop media literacy interventions, the Center for Media Literacy (2007) recommends that media literacy training should address five basic questions: (1) Who created this message?; (2) What creative techniques are used to attract attention?; (3) How might different people understand this message differently?; (4) What values, lifestyles and points of view are represented in, or omitted from, this message?; and (5) Why is this message being sent? We designed our major curriculum sections to address these basic questions (see link between these questions and YMD sections in Table 1). The YMD curriculum was designed to highlight the role of media messages and hone counter-arguing skills through three different media-literacy informed sections, and it culminates in the counter-advertising planning activity. The curriculum exposed adolescents to persuasive techniques and production components used in alcohol advertising and encouraged them to utilize this information in planning their own alcohol counter-advertisements. The first curriculum section focuses on developing an understanding of persuasive techniques (with a focus on four techniques – endorsement, sex, humor, and having fun/being one of the gang). These four persuasive techniques were selected based on examination of relevant research. For instance, a content analysis of persuasive themes in alcohol advertising from a popular youth-oriented magazine (e.g., Rolling Stone) over a three-year period indicated that product quality, humor, sex appeal, romance/relationships, and hanging out/partying were the most frequently used persuasive themes (Hill, Thomsen, Page, & Parrott, 2005). The curriculum also included endorsement as a persuasive strategy because it has been extensively used in counter-alcohol advertising (DeJong & Atkin, 1995). The second curriculum section consists of an analysis of claims or persuasive message content in alcohol advertising (including slogans and consequences), and the third section focuses on exploring the use of production components in alcohol advertising (i.e. the use of people, setting, font, and visuals). The curriculum ends with an involving application activity where groups plan an anti-alcohol poster that would be effective for students in their school.

Table 1.

Linking the YMD curriculum sections with the Center for Media Literacy’s (2007) 5 questions

| YMD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic questions | Who created this message? |

What creative techniques are used to attract attention? |

How might different people understand this message differently? |

What values, lifestyles and points of view are represented in, or omitted from, this message? |

Why is this message being sent? |

| 1. Understanding persuasion strategies | X | X | X | X | |

| 2. Identification of advertising claims | X | X | X | X | |

| 3. Understanding production components | X | X | X | X |

This paper further evaluates how well the students incorporated information learned through the YMD curriculum sections in creating their own print alcohol counter-advertisements. In addition it examines differences in application of YMD curriculum content to print alcohol counter-advertisements created by high school adolescents and college students. We anticipated similarities in the use of persuasion techniques and production components because these were presented and discussed in the YMD curriculum. However, we hypothesized that we would see differences in the kinds of message content (slogans and counter-arguments/consequences) that high school students and college students make. We expected developmental differences between the two groups of students (Ryan, 2009) would lead to more complex reasoning and arguments by college students. As well, increased exposure to alcohol in social settings and peer risk behavior (Ahlstrom & Osterberg, 2004; Millstein & Halpern–Felsher, 2002) may lead to more sophisticated arguments by college students, particularly in terms of emotional effects of alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors. This greater exposure for college students may also lead them to greater variety in poster focus, for example emphasizing the benefits of non-risk behavior rather than just highlighting the risks of alcohol use.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 49 print alcohol counter-advertisements created by small groups of high school students from across Pennsylvania and 23 created by college students in New Jersey (total N = 72). The participating high school students ranged in age from 14–17 years old and were about 63% female; identified themselves as White (63%), Hispanic/Latino (13%), Asian/Asian American (11%), African American/Black (9%), or American Indian/Alaskan Native (4%); represented rural, suburban, and urban school districts; and generally attended the10th grade. The college students ranged in age from 19–25 years old; were 62% female; and identified as White (56%), Asian/Asian American (21%), Hispanic/Latino (10%), or African American/Black (9%). For the counter-advertising poster planning exercise, students worked in small groups of 4–5 individuals. Each group received instructions to create an ad for other students in their school to “show why being alcohol free at their age is a good decision.” As a first step, groups were required to discuss and plan the messages for approximately 10 minutes before beginning message construction; this planning process plays a crucial role in actively involve the students in critically thinking about the messages (see TAI, Greene, current issue). The planning process involved first thinking about why some students choose to drink. This group process involved choosing the main point or message for their ad and focusing on one or several of a number of related counter-arguments to support their slogan (the poster could reflect one or many consequences of drinking/not drinking). The planning phase finally culminated in selection of particular persuasive techniques and production components to draw the target audience’s attention to the counter-ad. After completing message planning, the groups received poster-size paper and colored markers to create the counter-ad poster. The poster planning and creation process took between 20 and 25 minutes.

Qualitative Content Analysis

We used a combination of deductive and inductive coding (Elo & Kyngas, 2008) to analyze the alcohol counter-advertisements. First, we started with deductive coding, whereby the structure of analysis was operationalized based on our YMD curriculum content (see Greene et al., 2011). Therefore, the initial coding scheme for our study included the following categories: Poster content (presence/absence of slogans, counter-arguments/consequences), persuasion strategies (presence/absence of endorsement, glamour/sex appeal, having fun/being one of the group, humor/unexpected idea), and production components (presence/absence of people, setting, font, and visuals). Second, given that the main point of the poster differed with each ad, we used inductive coding to identify what slogans and consequences or counter-arguments were utilized in posters. This process included open coding and creating categories (Elo & Kyngas, 2008). Open coding refers to the analytical process of examining, comparing, and categorizing qualitative data to develop thematic concepts (Charmaz, 1983; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). We developed open coding categories directly and inductively from the raw data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), which included consequences such as hangover, sexual assault, liver damage, etc.

Next, we followed the procedures for axial coding, which involved coding similar data sequences to foster connections between emerging thematic concepts. This process grouped naturally-collapsing categories into higher order headings such as alcohol-related illness (e.g., hangovers, feeling sick, vomiting), alcohol-related disease (e.g., liver cirrhosis, hepatitis), drinking and driving (e.g., car crash, erratic driving), sexual encounter (e.g., rape, unplanned pregnancy), emotional consequences (e.g., sadness, crying, regret, shame), jailed/imprisoned (e.g., jailed, behind bars, etc.), death (e.g., grave, dead body, RIP), and positive consequences of not using alcohol (e.g., getting good grades, graduation, staying sober, achieving success, etc.). Further, the negative or harmful consequences such as alcohol-related illness, alcohol-related disease, drinking and driving, emotional consequences, and death were collapsed into negative consequences of drinking. Some posters compared positive and negative consequences of drinking while others reflected before and after effects of drinking, and the counter-arguing/consequences categorization included these. Similar procedures were employed for coding production components. Table 2 presents a list of coding categories and definitions.

Table 2.

Categories and Definitions Used to Code YMD Counter-advertising Posters

| Coding Categories | Definition |

|---|---|

| Poster Content | |

| 1. Slogans | Written words that communicate the essence of the advertisement’s selling proposition (Dowling & Kabanoff, 1996). |

| Stand-alone slogan | Written words in the ad communicate the message of the ad clearly, without reference to the image. |

| Image-related slogan | Written words in the ad communicate the message of the ad only in conjunction with the image. |

| 2. Counter-arguing/consequences | Evidence provided to support the slogans. In particular, information about the consequences of using the product, the benefits of the product use, and/or the values attained or emotions produced by product use or ownership (Ford, Smith, & Swassy, 1988). |

| Negative consequences | Information in the ad about the harmful consequences of alcohol use. |

| Alcohol-related illness | Information in the ad about any illness (e.g., vomiting, hangovers, feeling sick) due to alcohol use. |

| Alcohol-related disease | Information in the ad about any disease (e.g., cirrhosis, hepatitis) due to alcohol use. |

| Drinking and driving | Information in the ad about a car crash or erratic driving due to alcohol use. |

| Sexual encounter | Information in the ad about risky sexual exposure due to alcohol use (e.g., rape, unplanned pregnancy). |

| Emotional consequence | Information in the ad about emotional consequences of alcohol use (e.g., sadness, regret, guilt, shame). |

| Death | Information in the ad about death due to alcohol use (e.g., tombstone, grave, dead person, RIP). |

| Jail/Prison | Information in the ad about getting arrested or in a jail due to alcohol use. |

| Physical consequences | Information in the ad about unwanted physical consequences (e.g., beer belly, beet gut) due to alcohol use |

| Positive consequences | Information in the ad about the benefits of not drinking (e.g., looking sober, getting good grades, graduation, success in life). |

| Negative-positive consequence comparison | Both types of information (negative and positive consequences of alcohol use) contained in the ad. |

| Before-after depictions | Information in the ad regarding before and after consequences of alcohol use. |

| Persuasion strategies | |

| 1. Endorsement | Information in the ad about a celebrity or famous person or brand, used to highlight the counter-alcohol message. |

| 2. Glamour/sex appeal | Information in the ad about a sexy or glamorous person, used to illustrate the used to highlight the counter-alcohol message. |

| 3. Having fun/one of the group | Information in the ad about having fun in a group, used to highlight the counter-alcohol message. |

| 4. Humor/unexpected | Funny, humorous, or unexpected information in the ad, used to highlight the counter-alcohol message. |

| Production components | |

| 1. People | Illustrations in the ad that depict people (either through human forms, stick figures, or both). |

| Human forms | Illustrations in the ad that depict people through human forms. |

| Stick figures | Illustrations in the ad that depict people through stick figures. |

| Both | Illustrations in the ad that depict people using both human forms and stick figures. |

| 2. Setting | Illustrations in the ad that depict a clear setting or location. |

| Party | Illustrations in the ad that depict a party scene or prom scene. |

| Beach | Illustrations in the ad that depict a beach side. |

| Accident site | Illustrations in the ad that depict an accident site. |

| Bathroom | Illustrations in the ad that depict a bathroom. |

| School | Illustrations in the ad that depict a school. |

| Sporting event | Illustrations in the ad that depict a sporting event. |

| Jail/prison | Illustrations in the ad that depict a jail, prison, or arrest in a cop car. |

| Living room | Illustrations in the ad that depict a living room scene. |

| Graveyard | Illustrations in the ad that depict a graveyard, tombstone, graves, RIP. |

| Hospital/rehab | Illustrations in the ad that depict a hospital or a rehabilitation clinic. |

| 3. Font | Number of fonts in written message, used to highlight the main point in the ad. |

| 1 font size | Use of 1 font size in the written message of the ad. |

| 2 font sizes | Use of 2 different font sizes in the written message of the ad. |

| > 2 font sizes | Use of more than 2 different font sizes in the written message of the ad. |

| 4.Use of color | Number of colors used in the ad |

| 5.Image size | Use of non-traditional sizes to illustrate the main point in the ad (e.g., alcohol bottle or beer can larger than the human person). |

| 6. Object placement | Use of objects (e.g., alcohol bottle/can, car crash, or a serious health consequence) placed in the middle of the poster or in a way that draws attention. |

For all coding categories, 1 = Present, 0 = Absent

Coding Procedures

In this study, the unit of analysis was the alcohol counter-advertisement posters created by high school student groups and college student groups. After completing open and axial coding and developing the categories, two college students coded each of the posters. The coders received extensive training prior to content analysis. The training sessions included group discussions about the meanings and nuances of the coded variables (Nelson & Paek, 2005). We utilized Krippendorf’s alpha to calculate intercoder reliability (Krippendorff, 2004a, 2004b). Krippendorff's alpha values should be above 0.8, with values above 0.7 considered acceptable for studies that require agreement of multiple observers/coders (Lombard, Snyder-Duch, & Bracken, 2002). Reliability coefficients for all coded variables exceeded acceptable levels, with values ranging from .71 to 1.00. Any disagreements were resolved by a third coder, resulting in 100% final agreement. This paper presents primarily descriptive data analysis with additional supplemental qualitative analysis.

Results

This results section is divided into the three coding subsections derived from the curriculum structure (poster content, persuasion strategies, and production components) and presents descriptive findings for both the high school and college students within each category. Table 3 displays the prevalence (count and frequency) and difference between poster content, persuasion strategies, and production components in high school and college student posters; not all coding categories are mutually exclusive.

Table 3.

Prevalence and Difference Between Content Categories in Counter-Alcohol Posters Created by High School and College Students

| Coding Categories | Frequency in 49 High School Student Posters n (%) |

Frequency in 23 College Student Posters n (%) |

χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poster Content | |||

| 1.Slogans | 49 (100%) | 23 (100%) | - |

| Stand-alone slogan | 8 (16.33%) | 6 (26.09%) | .95 |

| Image-related slogan | 41 (83.67%) | 17 (73.91%) | .95 |

| 2. Counter-arguing/consequences | 49 (100%) | 23 (100%) | - |

| Negative consequences^ | 33 (67.35%) | 14 (60.87%) | .80 |

| Alcohol-related illness | 20 (60.61%) | 6 (42.86%) | 1.47 |

| Alcohol-related disease | 3 (9.09%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Drinking and driving | 7 (21.21%) | 4 (28.57%) | - |

| Sexual encounter | 2 (6.06%) | 6 (42.86%) | - |

| Emotional consequence | 10 (30.30%) | 7 (50%) | .87 |

| Death | 11 (33.33%) | 2 (14.29%) | - |

| Jail/Prison | 6 (18.18%) | 3 (21.43%) | - |

| Physical consequences | 13 (39.39%) | 1 (7.14%) | - |

| Positive consequences | 3 (6.12%) | 3 (13.04%) | - |

| Negative-positive consq. comparison | 13 (26.53%) | 6 (26.09%) | .01 |

| Before-after depictions | 10 (20.41%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Persuasion strategies^ | |||

| 1. Endorsement | 6 (12.24%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| 2. Glamour/sex appeal | 6 (12.24%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| 3. Having fun/one of the group | 9 (18.37%) | 6 (26.09%) | .57 |

| 4. Humor/unexpected | 8 (16.33%) | 3 (13.04%) | - |

| Production components | |||

| 1. People | 38 (77.55%) | 22 (95.65%) | - |

| Human forms | 20 (52.63%) | 7 (31.82%) | .72 |

| Stick figures | 13 (36.84%) | 9 (40.91%) | .52 |

| Both | 5 (13.16%) | 6 (27.27%) | 3.05 |

| 2. Setting^ | 39 (79.59%) | 16 (69.57%) | .87 |

| Party | 7 (17.95%) | 4 (25%) | - |

| Beach | 5 (12.82%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Accident site | 5 (12.82%) | 3 (18.75%) | - |

| Bathroom | 5 (12.82%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| School | 2 (5.13%) | 4 (25%) | - |

| Sporting event | 5 (12.82%) | 4 (25%) | - |

| Jail/prison | 3 (7.69%) | 2 (12.5%) | - |

| Living room | 4 (10.26%) | 1 (6.25%) | - |

| Graveyard | 4 (10.26%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Hospital/rehab | 3 (7.69%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| 3. Font | 49 (100%) | 23 (100%) | - |

| 1 font size | 12 (24.49%) | 6 (26.09%) | .02 |

| 2 font sizes | 30 (61.24%) | 15 (65.22%) | .11 |

| > 2 font sizes | 7 (14.29%) | 2 (8.70%) | - |

| 4. Use of color | M = 6.49, SD = 2.02 | M = 6.78, SD = 1.51 | - |

| 1–2 colors = 1 | 3 (6.12%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| 3–5 colors = 2 | 8 (16.33%) | 4 (17.39%) | - |

| > 6 colors = 3 | 38 (77.55%) | 19 (82.61%) | .24 |

| 5. Image size | 10 (20.41%) | 5 (21.74%) | .02 |

| 6. Object placement | 24 (48.98%) | 10 (43.48%) | .19 |

Note: Chi-square cannot be calculated if cell n < 5.

Categories were not mutually exclusive.

Poster Content

The YMD curriculum reviewed slogans as representing the main point (or claim) made in the poster and counter-arguments/consequences as evidence used to support the main point, including negative consequences, positive consequences, negative-positive consequence comparison, and before-after depictions. We first present results about slogans followed by counter-arguments/consequences.

Slogans

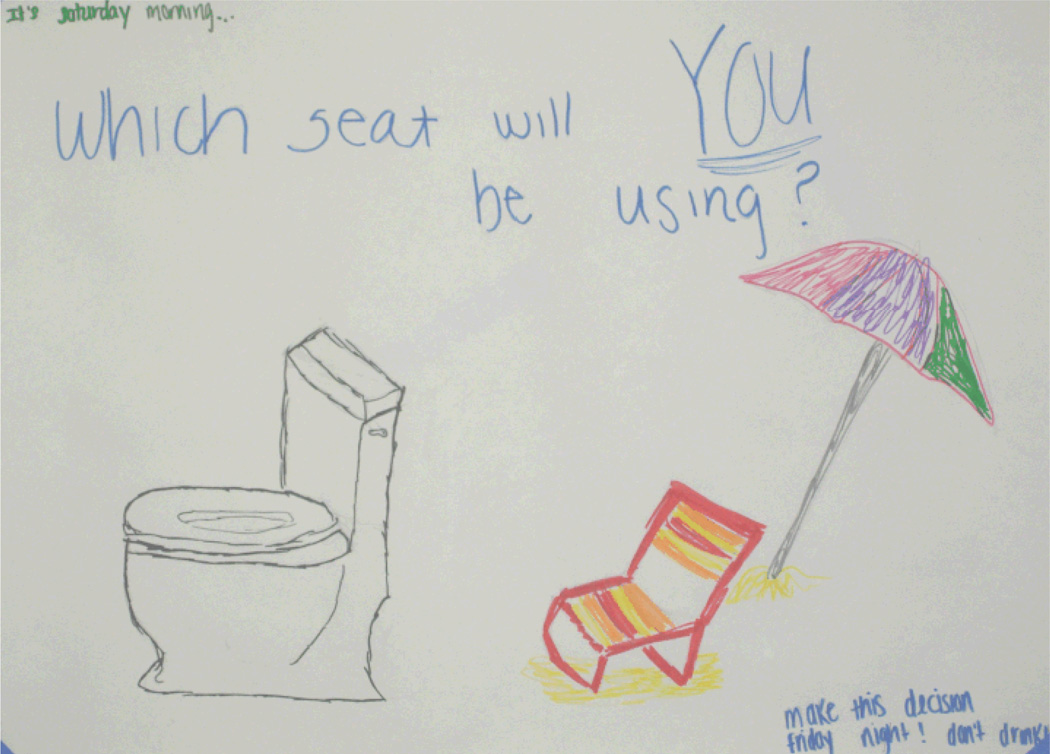

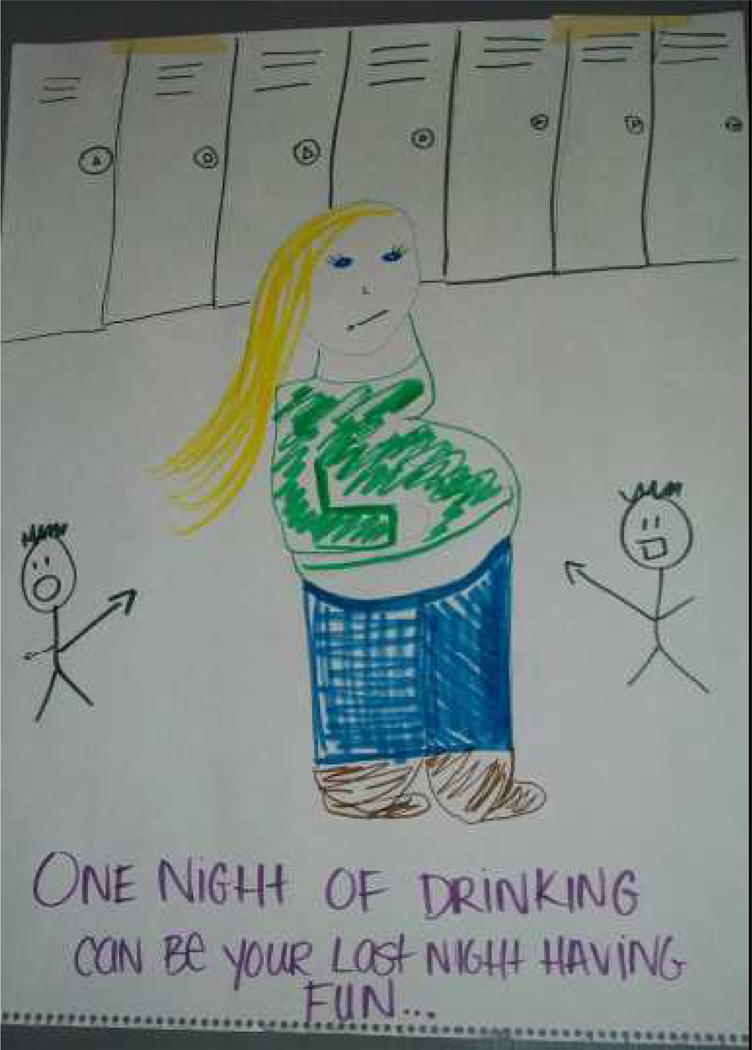

Results of the content analysis revealed that all of the posters included a slogan to highlight the main point/message of the ad, as recommended by the instructions for the activity. Overall, both high school students and college students used slogans in their counter-alcohol posters in order to highlight the main point or message of the ad. About three-times as many posters used image-related slogans (84% for high school; 74% for college) than stand alone slogans (16% and 26%, respectively); however, these differences between high school and college student posters were not statistically significant. Figures 1 and 2 provide examples of alcohol counter-advertisement posters created by high school students and college students in this project. The first example shows an ad created by a group of high school students that displayed a toilet seat and a beach chair. The slogan read, “Which seat will you be using” in bold and prominent letters. In smaller font, the poster included the message, “It’s Saturday morning. Make this decision Friday night. Don’t drink” (see Figure 1). The second example shows a college student ad that displays a sad pregnant woman at school with people laughing at her. The slogan read, “One night of drinking can be your last night having fun” (see Figure 2). Other examples of advertisements and their slogans include:

A high school student poster that displayed in the top-half people drinking in a car. In the bottom half, the poster showed the car smashed into a tree with all the occupants either dead or injured. The slogan read, “Believe it or not. This could be you.”

A high school student poster that displayed a banner with “Class of 2011” written on it. Underneath the banner, laid a coffin with beer cans littered around it. The slogan read, “He never thought he would miss his graduation.”

A college student poster included a slogan on at the, “It’s all fun and games until…” The rest of the poster is divided into 6 squares, each displaying a sad face and six different messages – “you break your leg,” “you get raped,” “you let down your little sister,” “you get kicked off your team,” “you lose your scholarship,” and “you embarrass yourself in front of your crush.”

Figure 1.

Sample Poster Created by High School Students.

Figure 1.

Sample Poster Created by College Students.

Alcohol consequences

The curriculum introduced the concept of counter-arguing and identifying arguments missing from advertisements. Based on these ideas, we examined what consequences students included in their posters to provide evidence for their main point (represented by the poster slogan). Results of the content analysis revealed that all of the posters presented counter-arguments/consequences, encouraging a further examination of exactly which consequences the posters highlighted most often. Results overall indicated similar patterns for both high school and college students. The posters displayed negative consequences of alcohol use the most (67% of the high school posters and 61% of the college posters), followed by displays of both negative consequences of alcohol use (e.g., prison) and positive consequences of not using alcohol (e.g., graduation) in the same poster (26% of both high school and college posters). Positive consequences of not using alcohol were displayed in far fewer posters overall (6% of the high school posters and 13% of the college posters).

The types of negative consequences displayed in posters differed between high school and college students, but the differences were not statistically significant. For high school student posters, alcohol-related illness was the most frequently depicted negative consequences of alcohol use, followed by physical consequences, death, emotional consequences, drinking and driving, jail, alcohol-related disease, and sexual encounters. For college student posters, emotional consequences were the most frequently portrayed negative consequence of alcohol use, followed by alcohol-related illness, sexual encounters, drinking and driving, jail, death, and physical consequences (alcohol-related diseases were not depicted in any of the college student posters). Finally, results indicated that about 20% of the posters created by high school students displayed consequences of alcohol use using a before-after depiction, but this form of presenting consequences was not utilized in any of the college student posters.

Persuasion Strategies

The curriculum identified four broad persuasion approaches utilized by advertisers; the coding accounted for these. Identifiable persuasion strategies were used in only 37% and 30% of the posters created by high school and college students respectively. Having fun/being one of the gang was the most frequently used persuasion strategy by both high school (18%) and college (26%) student posters. For instance, a poster (by high school students) illustrated a sexy couple on beach wearing swimwear and holding hands, and a lone male with a bottle of alcohol in hand. The poster identified the couple as sexy man, sexy woman, and the lone male as “nasty beer gut man”. The slogan read, “Does beer really make you look hot?” This poster utilized the persuasion strategies of having fun and glamour/sex appeal. Another poster (by college students) showed a sad prom queen behind bars holding a can of beer. Other people in the poster are depicted as having fun at the prom, celebrating getting their driver’s license, and shouting “We did it!” at graduation. The slogan read, “Don’t miss out!!” This poster also utilized the persuasion strategy of having fun.

High school students also used other persuasion strategies including humor/unexpected, followed by endorsement and glamour/sex appeal. For college students, humor/unexpected was the only other persuasion strategy utilized. One high school poster provided a great example of the use of multiple persuasion strategies in one message. It illustrated a glamorous woman on the left (identified as Taylor Swift) holding a bottle of water standing under a banner that read “Hollywood.” Two people appear on the right (a woman with beer belly and a much shorter man with beer belly, both appear unclean and are holding cans of beer). The man’s t-shirt has an arrow pointing to the woman, and read “She thinks my tractor’s sexy.” The slogan on the poster read, “Don’t drink. Your waist will shrink.” First, the poster used endorsement, showing Taylor Swift drinking water. Second, the poster utilized the strategy of glamour/sex appeal by showing Taylor Swift, wearing a glamorous dress and contrasting it with the shabby looking couple. Third, the poster utilized humor through the t-shirt logo, couple’s facial expressions, and size difference.

Production Components

The curriculum also addressed advertisers’ use of specific production strategies, and we coded student posters for these. All student posters incorporated a range of production components such as setting, image size, and object placement. People were depicted in 78% and 96% of the posters created by high school and college students respectively. Some of these people were drawn and others were included as stick figures. The inclusion of limited detail or stick figures is not surprising because of the limited time provided for poster production to emphasize message planning (see Greene, 2012). A clear setting was depicted in 80% and 70% of the posters created by high school and college students respectively, and this difference was not significant.

For font, most posters utilized at least two different font sizes and a number of different colors (range of 2–10 colors) for highlighting the message or main point of the posters. Production strategies of using non-traditional sizes and object placement were utilized about equally in the posters created by high school and college students respectively. For instance, a college student poster used a can of beer in the right half and a letter with “Welcome to University” in the left half. There are check boxes underneath the images, and the box under the university admission letter is “checked”. The word “OR” is written between the two images, and the slogan read, “What’s more important?” In this poster, object placement is utilized and the check mark under the university admission letter is used to emphasize the desirable decision, to choose education/future rather than the beer.

Another high school poster shows a car crash with stick figures around the crash with people bleeding, one person is shouting “Call 911”. A house appears on the right side of the poster, with a beer bottle the same size as the house next to it. The slogan read, “It only takes one!!” In this poster, the beer bottle is highlighted by making it similar in size to a house, drawing attention by manipulating image size and placement. Overall, these results indicate that the students understood the utilization of production components and incorporated those features in planning their own counter-alcohol posters.

Discussion

This study presents a content analysis of 72 print alcohol counter-advertisement posters created by youth who participated in the pilot testing of the YMD media literacy curriculum. Three major conclusions emerge from this analysis. First, adolescents seem much more likely to focus on negative consequences and negative-positive consequence comparisons as evidence in their self-created alcohol counter-advertisements rather than depicting positive consequences of being alcohol free. Within negative consequences, adolescents may focus on some negative consequences more than others. The most frequently displayed negative consequences of alcohol use were alcohol-related illness (such as vomiting, hangovers, feeling sick) followed by physical consequences for high school students. These findings suggest that long-term effects (such as liver damage, cirrhosis, and hepatitis) may not be perceived as important by adolescents compared with more immediate and short-term outcomes of alcohol use (such as vomiting and hangovers). This is consistent with literature that indicates that younger and middle adolescents may not have developmental maturity sufficient to anticipate longer-term future consequences.

To encourage more emphasis on the positive consequences of not using alcohol, future revisions of the YMD curriculum may provide more examples and promote the depiction of positive consequences of low-risk behavior through both discussion examples and instructions for the poster-planning activity. A quarter of the posters did display negative-positive consequence comparisons. This finding reaffirms the need for behavior consequences along with social modeling appeals that emphasize portrayal of desirable behavior to provide positive reinforcement for the viewer (Slater, 1999). Hecht and Miller-Day (2009) also found that positive images of youth refusing drugs are central to prevention messages in the keepin’ it REAL curriculum (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009). An enhanced focus on positive portrayals in the YMD curriculum may help provide positive reinforcement for the students’ anti-risk choices, and the curriculum could enhance and extend depictions of the positive aspects of non-use. For instance, more images of enjoyable non-alcohol related activities may provide positive reinforcement for adolescents to refrain from alcohol use. As well, this comparison between negative-positive consequences may be highlighted using before/after depictions. In the current study, high school students utilized this before/after strategy but not college students. Future research can further explore why this difference emerged, but the before/after depiction is more basic and widely used (e.g., smoking appeals focusing on the lung of a non-smoker compared to a smoker) and therefore may be more accessible to less developmentally sophisticated middle adolescents. The college students chose different approaches that may be more complex, such as positive consequences of non-use.

Second, results indicated that image-related slogans were used more frequently than stand-alone slogans. However, the few stand-alone slogans that the student groups came up with suggest that the production value of “catchy” slogans could also be incorporated in future interventions. Research suggests that adolescents understand and have opinions regarding persuasive message effects on similar aged peers (e.g., Cho & Boster, 2008; Henriksen & Flora, 1999), but unfortunately peer-created messages have not been utilized widely in prevention planning to date (for exception see Hicks, 2001; see also Greene & Hecht, current issue) and have not been evaluated systematically for effectiveness. We anticipate that slogans may also help with consistency and branding of the messages if they are “stand-alone” rather than tied to images in the posters, and this could be incorporated in future YMD efforts. Austin et al. (1999) pointed out that alcohol counter-advertisements have a lackluster flavor that dampens effectiveness when compared to alcohol advertisements. Creating more catchy slogans may enhance counter alcohol advertisements and should be examined in future research.

Third, the students did not use all persuasive techniques that were covered in the curriculum, and the majority of the posters did not use any of the specific persuasive techniques. The persuasion strategies that were utilized in the posters emphasized having fun as one of the gang, but the students did not utilize otherwise common strategies such as sex/glamour or endorsement that may be more difficult for youth to construct in a shorter time. In order to encourage better use of persuasive techniques, students may be instructed to plan their posters by choosing a persuasive strategy from the lesson and plan accordingly.

Some of the posters made effective use of production components by enlarging the font of slogans or include people and setting features that resonate with the target audience. It appears that the curriculum was effective in increasing awareness of a variety of production techniques. Past research suggests that effective messages geared to adolescents should incorporate good production values (Slater & Rouner, 1996), and the YMD curriculum appears to provide adolescents with some of the skills needed to plan detailed message features for their posters.

Therefore, based on analyses of the posters created by students participating in the YMD curriculum, our recommended changes to the curriculum include the following: (a) planning a poster should begin with the identification of a specific persuasion strategy to reflect the main point of the ad, (b) discuss the utility of slogans within production components (with examples), and students planning the posters should be encouraged to come up with a catchy slogan to “sell” their message, and (c) the curriculum could compare negative consequences of risk taking with positive consequences of risk avoidance approaches.

Limitations

The fact that high-school students and college students from only two states created the posters means that the posters may not represent what adolescents from other states or different age-groups might create. In addition, the time (~20 minutes) and resource constraints on planning and producing the posters may have compromised the quality and content to a lessor extent because the content was the focus of the initial planning. This limited time was designed, in part, to focus students on the planning portion of the process (see Greene, current issue). Students may have been able to generate more compelling, comprehensive, and attention grabbing messages in support of being alcohol free if given more time and resources, and potentially more instruction in media literacy. For example, more of the groups may have gone beyond using stick figures and/or incorporated more use of the endorsement or glamour/sex appeal persuasive techniques.

Conclusions and Future Work

This study provides a first step in examining messages planned and produced from adolescents engaged in alcohol prevention efforts as part of a media literacy intervention. Future research could examine how other adolescents perceive these kinds of adolescent-created alcohol counter-advertisements along with assessing the effectiveness of such counter-advertisements. A different study could also evaluate if adolescent engagement in this type of message creation leads to self-persuasion and increases resistance to other alcohol-related influences (and therefore decreases alcohol use). This study points to key message themes that may prove effective in adolescent underage drinking prevention efforts, including portrayals of negative consequences of use or presenting a negative-positive consequence comparison.

Research indicates that adolescents want to be listened to, not talked at, and that simple, honest messages work better than complex, misleading messages (e.g., Schiff, 2007). Involving adolescents in counter ad campaigns to generate messages that resonate well with similar aged adolescents may work as the foundation for effective strategies for preventing underage alcohol use (see Greene, 2012). Media literacy provides a useful venue for engaging adolescents and young adults in critical examination of persuasive alcohol advertising and in creation of alcohol counter-advertisements.

Finally, using similar persuasion and production strategies as used in alcohol advertisements can help increase the appeal of alcohol counter advertisements (Austin et al., 1999) and should be examined in audio-visual advertisements as well. Prior research on tobacco counter-advertising (American Legacy Foundation’s “Truth” campaign) indicates effectiveness for reducing smoking initiation (Apollonio & Malone, 2009). A similar counter-advertising campaign for alcohol reduction is needed and may serve to counter harmful health messages promoted by media.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by grant number R21 DA027146 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Rutgers University (grant recipient), Kathryn Greene, Principal Investigator. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Smita C. Banerjee, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Kathryn Greene, Department of Communication, Rutgers University.

Michael L. Hecht, Department of Communication Arts & Sciences, Pennsylvania State University

Kate Magsamen-Conrad, Department of Communication, Rutgers University.

Elvira Elek, RTI International.

References

- Agostinelli G, Grube JW. Alcohol counter-advertising and the media: A review of recent research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26(1):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostinelli G, Grube JW. Tobacco counter-advertising: A review of the literature and a conceptual model for understanding effects. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:107–127. doi: 10.1080/10810730305689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom SK, Osterberg EL. International perspectives on adolescent and young adult drinking. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:258–268. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apollonio DE, Malone RE. Turning negative into positive: Public health mass media campaigns and negative advertising. Health Education Research. 2009;24:483–495. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Pinkleton BP, Fujioka Y. Assessing pro-social message effectiveness: Effects of message quality, production quality and persuasiveness. Journal of Health Communication. 1999;4:195–210. doi: 10.1080/108107399126913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SC, Greene K. Analysis versus production: Adolescent cognitive and attitudinal responses to anti-smoking interventions. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:773–794. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SC, Greene K. Anti-smoking initiatives: Examining effects of inoculation based media literacy interventions on smoking-related attitude, norm, and behavioral intention. Health Communication. 2007;22:37–48. doi: 10.1080/10410230701310281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SC, Greene K. “Yo! This is no lie, if you smoke, you die”: A content analysis of anti-smoking posters created by adolescents. Journal of Substance Use. 2012 doi: 10.3109/14659891.2011.615883. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Alcohol Marketing and Youth. Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television. 2010:2001–2009. Retrieved from http://www.camy.org/bin/u/r/CAMYReport2001_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Media Literacy. CML’s five key questions. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.medialit.org/sites/default/files/14A_CCKQposter.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: An explication and interpretation. In: Emerson R, editor. Contemporary field research: A collection of readings. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Company; 1983. pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Boster FJ. First and third person perceptions on anti drug ads among adolescents. Communication Research. 2008;35:169–189. [Google Scholar]

- Collins J, Doyon D, McAuley C, Quijada AI. Reading, writing, and deconstructing: Media literacy as part of the school curriculumIn. In: Wan G, Gut DM, editors. Bringing schools into the 21st century (Vol. 7): Explorations of educational purpose. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Communications. Children, adolescents, and advertising. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2563–2569. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine DM, Haley GE. Visual messages: Integrating imagery into instruction. Englewood, CO: Leaders Ideas Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Atkin CK. A review of national television PSA campaigns for preventing alcohol-impaired driving, 1987–1992. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1995;16:59–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Hoffman KD. A content analysis of television advertising for the Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program Media Campaign, 1993–1996. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2000;6(3):27–39. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200006030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Haviland ML, Messeri P, Healton CG. Evidence of a dose–response relationship between “Truth” antismoking ads and youth smoking. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:425–431. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gosin M, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Keepin’ it REAL: A drug resistance curriculum tailored to the strengths and needs of pre-adolescents of the Southwest. The Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:119–142. doi: 10.2190/DXB9-1V2P-C27J-V69V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K. The Theory of Active Involvement: Processes underlying interventions that engage adolescents in message planning and/or production. Health Communication. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.762824. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Elek E, Magsamen-Conrad K, Banerjee SC, Hecht ML, Yanovitzky I. Developing a brief media literacy intervention targeting adolescent alcohol use: The impact of formative research; Paper presented at the DC Health Communication Conference; Fairfax, VA. 2011. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Hecht ML. Introduction for Symposium on engaging youth in prevention message creation: The theory and practice of active involvement interventions. Health Communication. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.762825. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube JW, Wallack L. Television beer advertising and drinking knowledge, beliefs, and intentions among school children. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:254–259. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harthun ML, Dustman PA, Reeves LJ, Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF. Using community-based participatory research to adapt keepin' it REAL: Creating a socially, developmentally, and academically appropriate prevention curriculum for 5th graders. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2009;53(3):12–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Kayo R. Cultural factors in adolescent prevention: Multicultural approach works well. Addiction Professional. 2004;2:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Krieger JL. The principle of cultural grounding in school-based substance abuse prevention. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2006;25:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Miller-Day M. The drug resistance strategies project: Using narrative theory to enhance adolescents’ communication competence. In: Frey L, Cissna K, editors. Routledge handbook of applied communication. New York: Routledge; 2009. pp. 535–557. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Flora JA. Third-person perception and children: Perceived impact of pro and anti-smoking ads. Communication Research. 1999;26:643–665. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JJ. The strategy behind Florida’s“truth” campaign. Tobacco Control. 2001;10(1):3–5. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SC, Thomsen SR, Page RM, Parrott N. Alcohol advertisements in youth-oriented magazines: Persuasive themes and responsibility messages. American Journal of Health Education. 2005;36:258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Siegel M, Jernigan DH, Wulach L, Ross C, Dixon K, Ostroff J. Adolescent exposure to alcohol advertising in magazines: An evaluation of advertising placement in relation to underage youth readership. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004a. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research. 2004b;30:411–433. [Google Scholar]

- Kubey R. How media education can promote democracy, critical thinking, health awareness, and aesthetic appreciation in young people. SIMILE: Studies In Media & Information Literacy Education. 2005;5(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, Austin EW. Media literacy education for elementary school substance use prevention. Pediatrics. 2010;126:525–531. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Cheng IH. Assessing the TARES as an ethical model for antismoking ads. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15:55–75. doi: 10.1080/10810730903460542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Hecht ML, Miller-Day MA, Elek E. Evaluating mediated perception of narrative health messages: The perception of narrative performance scale. Communication Methods and Measures. 2011;5:126–145. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2011.568374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin ML. The ABCs of strategic communication: Thousand of terms, tips, and techniques that define the professions. Bloomington, IN: Author House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Bracken CC. Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research. 2002;28:587–604. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie R, Johnson N, Chapman S, Holding S. Smoking-related disease on Australian television news: Inaccurate portrayals may contribute to public misconceptions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2009;33:144–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Day M, Hecht ML. Narrative means to preventative ends: A narrative narrative engagement framework for designing prevention interventions. Health Communication. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.762861. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein SG, Halpern–Felsher BL. Judgments about risk and perceived invulnerability in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MR, Paek HJ. Cross-cultural differences in sexual advertising content in a transnational women’s magazine. Sex Roles. 2005;53:371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkleton BE, Austin EW, Cohen M, Miller A, Fitzgerald E. A statewide evaluation of the effectiveness of media literacy training to prevent tobacco use among adolescents. Health Communication. 2007;21:23–34. doi: 10.1080/10410230701283306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RG. Age differences in personality: Adolescents and young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H. Alcohol advertising and youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl):173–181. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff J. How to market to teens: keep it real and simple. 2007 Retrieved from: www.ecommerce-guide.com. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Drinking and driving PSAs: A content analysis of behavioral influence strategies. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1999;44:68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rouner D. Value-affirmative and value-protective processing of alcohol education messages that include statistical evidence or anecdotes. Communication Research. 1996;23:210–235. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Foxcroft DR. The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behavior in young people: Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:51–62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder L, Milici F, Slater M, Sun H, Strizhakova Y. Effects of alcohol advertising exposure on drinking among youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;1:18–24. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LB, Hamilton MA. A meta-analysis of U.S. health campaign effects on behavior: Emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information, and beware the secular trend. In: Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 357–384. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon BJ, Hendry P, Kalynych C, Taylor P, Tepas JJ. Do perceptions of effective distractive driving public service announcements differ between adults and teens? The Journal of Trauma. 2010;69(Suppl 4):S223–S226. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f1eb07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner K. The tale of the elephant: Media education in the United States. In: Bazalgette C, Bevort E, Savino J, editors. New directions: Media education worldwide. London, UK: British Film Institute; 1992. pp. 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JR, Hecht ML, Wagstaff DA, Elek E, Ndiaye K, Dustman P, Marsiglia FF. Communicating prevention: The effects of the keepin’ it REAL classroom videotapes and televised PSAs on middle-school students’ substance use. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2006;34:209–227. [Google Scholar]