Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that the functions of presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are tightly regulated by protein kinases. We previously reported that cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) directly phosphorylates mGluR2 at a single serine residue (Ser843) on the C-terminal tail region of the receptor, and that phosphorylation of this site inhibits coupling of mGluR2 to GTP-binding proteins. This may be the mechanism by which the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin inhibits presynaptic mGluR2 function at the medial perforant path-dentate gyrus synapse. We now report that PKA also directly phosphorylates several group III mGluRs (mGluR4a, mGluR7a, and mGluR8a), as well as mGluR3 at single conserved serine residues on their C-terminal tails. Furthermore, activation of PKA by forskolin inhibits group III mGluR-mediated responses at glutamatergic synapses in the hippocampus. Interestingly, β-adrenergic receptor activation was found to mimic the inhibitory effect of forskolin on both group II and III mGluRs. These data suggest that a common PKA-dependent mechanism may be involved in regulating the function of multiple presynaptic group II and group III mGluRs. Such regulation is not limited to the pharmacological activation of adenylyl cyclase but can also be elicited by the stimulation of endogenous Gs-coupled receptors, such as β-adrenergic receptors.

Keywords: β-adrenergic, cAMP-dependent protein kinase, mGluR4, mGluR7, mGluR8, phosphorylation

The metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) belong to the class of GTP-binding protein (G-protein)-coupled receptors that contain seven transmembrane domains. Eight mGluR subtypes have been cloned and are classified into three groups. Group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and mGluR5) activate phospholipase C through coupling to the Gq class of G-proteins, and are selectively activated by 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG). Group II (mGluR2 and 3) and group III (mGluR4, 6, 7, and 8) mGluRs inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity through coupling to the Gi/Go class of G-proteins, and are selectively activated by (2S,2′R,3′R)-2-(2′,3′-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine (DCG-IV) and (L)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (L-AP4), respectively (for review, see Conn and Pin 1997). Splice variants have been found for both group I mGluRs and group III mGluRs. Rat mGluR1 exists in five splice forms. The mGluR1a subtype has a long intracellular C terminal tail whereas mGluR1b, mGluR1c, and mGluR1d have short C termini. The mGluR1e splice form is not a functional receptor but consists of only of the N-terminal domain of the protein (Pin et al. 1992; Tanabe et al. 1992; Pin and Duvoisin 1995; Mary et al. 1997). Similar to mGluR1a, splice variants of rat mGluR5 receptors (mGluR5a and 5b) possess a long intracellular C-terminal tail (Minakami et al. 1994). With the exception of mGluR6, each group III mGluR subtype, has two splice variants (mGluR4a and 4b, 7a and 7b, and 8a and 8b, respectively), each with a relatively short intracellular C-terminal tail (Thomsen et al. 1997; Corti et al. 1998).

One primary function of group II and group III mGluRs in the CNS is to presynaptically reduce glutamate release and thereby inhibit excitatory transmission at glutamatergic synapses (for review, see Conn and Pin 1997). Increasing evidence suggests that the function of presynaptic mGluRs is tightly regulated by protein kinases. For instance, activation of protein kinase C (PKC) inhibits the function of multiple presynaptic group II and group III mGluR subtypes at several glutamatergic synapses (Swartz et al. 1993; Kamiya and Yamamoto 1997; Macek et al. 1998). Furthermore, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) inhibits the function of group II mGluRs at excitatory synapses in area CA3 of the hippocampus (Kamiya and Yamamoto 1997; Maccaferri et al. 1998) and at the medial perforant path-dentate gyrus (MPP-DG) synapse (Schaffhauser et al. 2000). We recently reported that PKA-induced inhibition of mGluR2 is mediated by direct phosphorylation of the receptor at a single site (Ser843) on its C-terminal tail. Phosphorylation of this site inhibits mGluR2-mediated responses by inhibiting coupling of the receptor to G-proteins (Schaffhauser et al. 2000). Whether PKA-induced phosphorylation of mGluRs is restricted to mGluR2 or is a general mechanism involved in the regulation of multiple presynaptic mGluRs is not known. Furthermore, it is not clear whether this response can only be obtained with adenylyl cyclase activators, such as forskolin, or whether it is physiologically relevant and can be elicited by agonists of receptors coupled to the activation of adenylyl cyclase (and PKA). We now report that PKA directly phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of several group III mGluR subtypes (mGluR4a, mGluR7a, and mGluR8a) as well as mGluR3. For all the mGluRs studied, PKA phosphorylates a single serine residue in their C-terminal region. In addition, the phosphorylation site is highly conserved in all group III mGluRs except for mGluR4b. Furthermore, activation of PKA inhibits the function of presynaptic mGluRs at multiple hippocampal synapses and this effect can be elicited by activation of β-adrenergic receptors when examining effects mediated by representative group III (mGluR7) and group II (mGluR2) mGluRs.

Materials and methods

Materials

L-AP4 and DCG-IV were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Ballwin, MO, USA). Purified PKA catalytic subunit, PKA inhibitor 6–22 amide (PKI), forskolin, and Rp-isomer of cAMPs (Rp-cAMPs) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Quik-Change™ site-directed mutagenesis kit and BL21 Gold super-competent cells were obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). The glutathione S-transferase (GST) Gene Fusion System was purchased from Pharmacia Biotech (Pitscataway, NJ, USA). [γ-32P]ATP was obtained from NEN-Dupont (Boston, MA, USA). Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany). Isoproterenol and all other materials were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antisera against mGluR7a and mGluR4a were prepared and affinity-purified previously (Bradley et al. 1996).

Plasmid constructions and mutagenesis

The C-terminal tails of mGluR4a, mGluR7a, and mGluR8a were amplified by PCR using directional primers engineered with restriction sites 5′ proximal to the end of the oligomer. The PCR product was then digested with EcoR1 and Not1 and subcloned in-frame into the polylinker region of pGex6P3 (Pharmacia), a GST-fusion protein bacterial expression vector. Point mutations were introduced into the fusion proteins using Stratagene’s Quik-Change™ site-directed mutagenesis system in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. Each construct was sequenced for verification.

GST-fusion protein generation and purification

GST fusion proteins containing the wild-type or mutant C-terminal tails of mGluR4a, 7a, and 8a were purified from bacterial lysates according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Pharmacia). These were used for in vitro phosphorylation assays. For phosphopeptide analysis, the C-terminal tails of wild-type mGluRs were cleaved from GST using PreScission Protease (Pharmacia), and purified by HPLC.

Protein preparations from the hippocampus and cerebellum

Hippocampi of 6-week-old rats were dissected out and cut into slices using a McIlwayne tissue chopper. The slices were briefly incubated in ice-cold aCSF (artificial cerebral spinal fluid) bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2, and then washed twice with an ice-cold lysis solution [50 mM HEPES, 10 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaCl, plus protease inhibitors (Complete tablets from Roche) and a phosphatase inhibitor (1 mM NaVO4)]. Cerebella of 6-week-old rats were dissected out and then homogenized in the same ice-cold lysis solution. Slices or homogenates were then sonicated for about 1 min on ice. Triton X-100 was added to 1% final concentration, and mixed with tissue on an orbital shaker at 4°C for 15 min. Lysates were then centrifuged at 14 000 g for 15 min, and supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes. Total protein concentrations were determined using the method of Bradford (Pierce BCA reagent) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

In vitro phosphorylation assay

The GST-fusion proteins or total proteins from the hippocampus or cerebellum were phosphorylated in vitro by PKA with [γ-32P]ATP, as previously described (Schaffhauser et al. 2000). The phosphorylated GST-fusion proteins were then separated by electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gels. The dried gel was exposed to a phosphoscreen or X-ray film, and radioactivity in the bands was quantified with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. Phosphorylated proteins from the hippocampus or cerebellum were immunoprecipitated with mGluR4 or mGluR7 antibodies before being separated by electrophoresis.

Immunoprecipitation

Four micrograms of primary antibody against mGluR4 or mGluR7 (Bradley et al. 1996, 1998, 1999) were added to 100–200 μg proteins from the hippocampus or cerebellum. After overnight incubation at 4°C on a rotary shaker, 100 μL of 50% slurry of protein A sepharose was added for an additional hour. The whole reactions were then centrifuged briefly at 14 000 g, washed three times in lysis solution, and resuspended in SDS loading buffer at 1 × final concentration for gel electrophoresis. Phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. In parallel experiments, western blotting was used to confirm the molecular size of immunoprecipitated receptors.

Phosphopeptide analysis

The C-terminal peptide of mGluR7a (m7CTX) and mGluR4a (m4CTX) was purified by microbore reversed-phase high pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a Jupiter C4 silica column (2.1 × 150 mm, Phenomenex) equilibrated in 0.1% aqueous TFA and eluted using a linear gradient of acetonitrile. The sequence of m7CTX is GPLGSPNSHPELNVQKRKRSF-KAVVTAATMSSRLSHK PSDRPNGEAKTELCENVDPN-SPAAKKKYVSYNNLVI, and that of m4CTX is GPLGSPNSEQNVPKRKRSLKAV VTAATMSNKFTQKGNFRPNGEAKSELCENLETPALA TKQTYVTYTNHAI. The purified m7CTX or m4 CTX was phosphorylated as described above except that 10 mM cold ATP was added instead of [γ-32P]ATP. Phosphorylated m7CTX or m4CTX was then HPLC-purified prior to trypsin digestion. The singly phosphorylated proteins as determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), m4CTX (mass = 7817.0 amu, expected mass = 7816.7 amu), and m7CTX (mass = 8040.4 amu, expected mass = 8042.1 amu), were digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) and the peptides were separated by RP-HPLC on a C18 silica column (0.5 × 150 mm, Zorbax SBC18; Microtech Scientific). The masses of the peptides were determined by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in a model API3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a MicroIonSpray source (PE-Biosystems/SCIEX) and operated in the liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) mode. Phosphorylated peptides in the digests were identified by ESI-MS using the on-line precursor ion scanning technique, which is based on monitoring of the loss of the phosphate group from phosphopeptides (Schaffhauser et al. 2000); the PE-SCIEX BiotoolBox software was used to perform mass calculations and to identify the peptides.

Generation of mGluR8-deficient mice

The mouse mGluR8 gene was disrupted by replacing the first 4 transmembrane domains of the receptor with the neomycin resistance gene driven by the thymidine kinase promoter. The targeting vector was electroporated in W9.5 embryonic stem cells, and G418-resistant clones were screened by PCR and Southern blot to verify the occurrence of homologous recombination. Chimeric mice with germline transmission of the targeted allele were mated with 129S3/SvImJ mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Western blot analysis confirmed the absence of mGluR8 receptors in the transgenic animals (Duvoisin et al. 1999; Zhang and Duvoisin, unpublished observations).

Field potential recording

Hippocampal slices were prepared from 5- to 7-week-old rats, and field potential recordings were performed at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 (SC-CA1) and medial perforant path-dentate gyrus (MPP-DG) synapses as described previously (Macek et al. 1996). Hippocampal slices from 5- to 7-week-old wild-type mice (129S3/SvImJ; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and mGluR8 knockout mice (129S3/SvImJ-mGluR8) were prepared using the same method. Field potential recordings were performed at the lateral perforant path-dentate gyrus (LPP-DG) synapses as described previously (Macek et al. 1996). Both stimulating and recording electrodes were placed in the outer third of the molecular layer in the dentate gyrus, and the previously described criteria were used to confirm selective recording from the LPP-DG synapses (Kahle and Cotman 1993; Macek et al. 1996). The stimulus intensity was adjusted until field potential responses to afferent stimulation were about 50% of the maximal response. Drugs were delivered to the perfusion medium, which ran at 100 μL/min with the use of a Sage syringe pump.

Results

PKA directly phosphorylates group III mGluRs

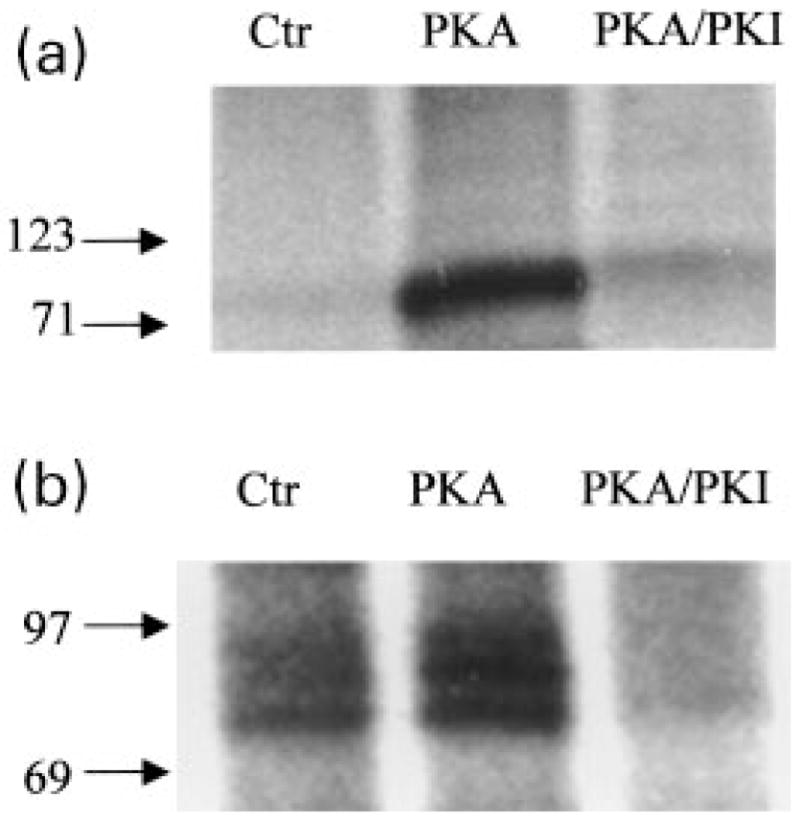

Previously, we showed that PKA phosphorylates mGluR2 at a single site (Ser843) on its C-terminal tail (Schaffhauser et al. 2000). By sequence alignment we also showed in the same study that all group II and group III mGluR subtypes contain one or two PKA consensus sites in the same region of the protein, suggesting that these receptors might also be phosphorylated by PKA. To determine whether group III mGluRs are phosphorylated by PKA in a manner similar to mGluR2, we first performed experiments to examine whether purified PKA catalytic subunit phosphorylates group III mGluRs in rat brain. Total proteins prepared from rat cerebella and hippocampi were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of the purified catalytic subunit of PKA. mGluR4 and mGluR7 proteins were then immunoprecipitated from the phosphorylated cerebellum and hippocampal proteins, respectively. A robust PKA-induced increase in phosphorylation of mGluR 4 and mGluR7 was found, which was inhibited by PKI (1 μM), a highly specific peptide inhibitor of PKA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PKA phosphorylates mGluR7 in the hippocampus and mGluR4 in the cerebellum. Autoradiographs showing PKA-induced phosphorylation of mGluR7 immunoprecipitated from total hippocampal proteins (a), and phosphorylation of mGluR4 immunoprecipitated from total cerebellum proteins (b). The molecular weights of the predominant phosphorylated band in (a) and the upper most band in (b) are consistent with that of mGluR7 and mGluR4, respectively, as determined by western blot analysis. The multiple bands in (b) may represent degradation products of mGluR4. In both cases, phosphorylation of the receptors was inhibited by the presence of a selective inhibitor of PKA (1 μM PKI). 10 U of purified PKA was used per 100 μg protein in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Each graph is representative of three independent experiments. Numbers beside arrows pointing to the graphs refer to the molecular weight markers.

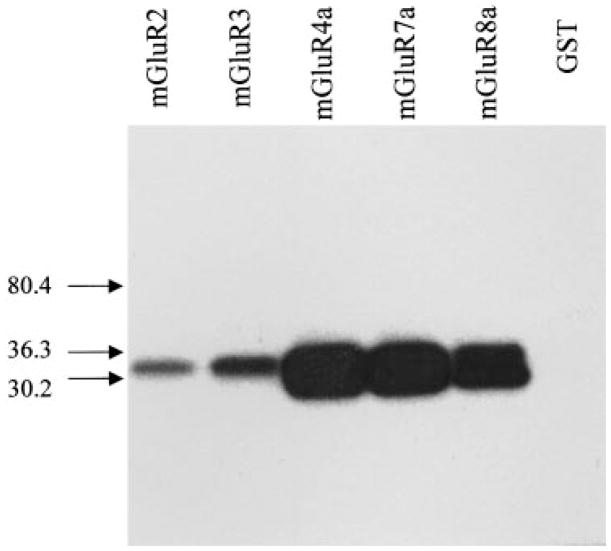

PKA directly phosphorylates group III mGluRs at their C-terminal regions

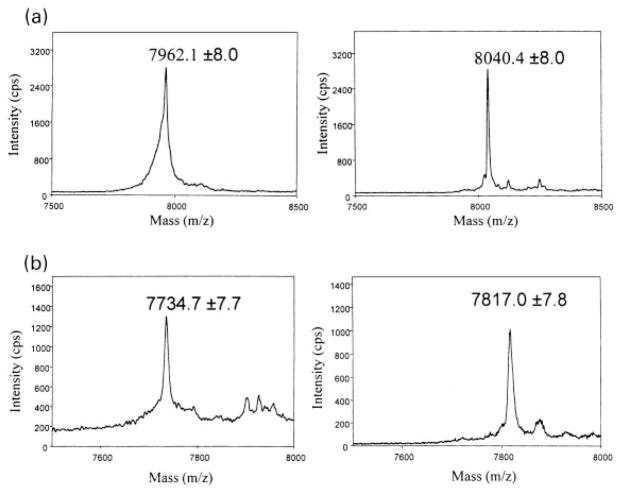

To determine whether PKA phosphorylates mGluR3 and group III mGluRs in their C-terminal tail, we prepared fusion proteins containing this region of mGluR3, mGluR4a, mGluR7a, and mGluR8a. In vitro phosphorylation assays revealed that PKA directly phosphorylates the C-terminal fusion proteins of all group II and group III mGluRs tested (Fig. 2). With the same amount of protein used under the same experimental condition, group III mGluRs were more heavily phosphorylated than group II mGluRs. Direct PKA phosphorylation of C-terminal tails of mGluR4a (m4CTX) and mGluR7a (m7CTX) was also confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS before and after in vitro phosphorylation (Fig. 3). The mass differences between the phosphorylated and the control constructs were 78.3 amu in the case of m7CTX and 82.3 amu in the case of m4CTX. These are in good agreement with the expected 80 amu difference for a single phosphorylation site given the 0.1% mass error of the instrument in linear mode of operation using external calibration. The m4CTX and m7CTX used in MALDI-TOF MS were cleaved from GST and HPLC-purified before in vitro phosphorylation (see Methods and materials).

Fig. 2.

C-terminal tails of group III mGluRs are PKA substrates. The autoradiograph (representative of three independent experiments) shows that PKA phosphorylated all group II and III mGluRs tested (mGluR6 not tested). Protein (GST alone) expressed from the pGEX vector yielded no significant phosphorylation. One microgram of protein was used for each lane. Numbers besides arrows pointing to the graph refer to the molecular weight markers.

Fig. 3.

MALDI-MS confirmed m7CTX and m4CTX were phosphorylated by PKA with a ~80 m/z mass shift. (a) m7CTX construct (GPLGSPNSHP ELNVQKRKRS FKAVV-TAATM SSRLSHKPSD RPNGEAKTEL CENVDPNSPA AKKKYVSYNN LVI) was HPLC purified and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix (calculated m/z = 7962.0 before phosphorylation, left panel, and m/z = 8042.0 after incorporation of a single phosphate group, right panel). (b) m4CTX construct (GPLGSPNSEQ NVPKRKRSLK AVVTAATMSN KFTQKGNFRP NGEAK-SELCE NLETPALATK QTYVTYTNHA I) was analyzed as described for m7CTX (calculated m/z = 7735.7 before phosphorylation, left panel, and m/z = 7815.7 after incorporation of a single phosphate group, right panel).

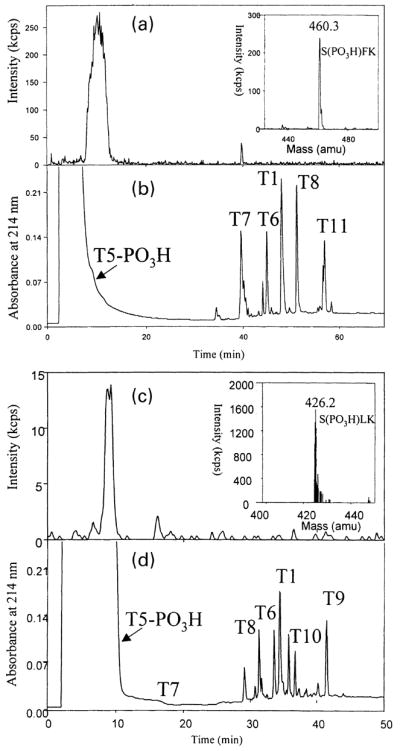

PKA phosphorylates group III mGluRs at single serine residues at their C-terminal tails

Two potential phosphorylation sites for PKA, Ser862 and Ser877, are present in the C-terminal tail of mGluR7a, while mGluR4a and mGluR8a C-terminal tails only contain single consensus sites (Ser859 and Ser855, respectively). To determine the phosphorylation sites on two representative group III mGluRs, quantitative phosphopeptide analysis of tryptic peptides was used. HPLC-purified m4CTX and m7CTX peptides were incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKA, purified again by HPLC, and digested with trypsin. Figure 4(a) shows a total ion current trace of precursor ion scanning (phosphate, −79 amu) LC-MS experiment for m7CTX tryptic peptides. The mass spectrum of the only phosphopeptide present in the m7CTX tryptic digest corresponds to residues 20–22 (SFK) of m7CTX as shown in the insert. The UV trace of the same run (Fig. 4b) shows the peaks that are assigned to tryptic peptides of m7CTX. Peak T5-PO3H corresponds to residues 20–22 (SFK) in m7CTX, in which the only possible phosphorylated residue is Ser862. Similarly, the only phosphorylated peptide found for m4CTX corresponds to residues 18–20 (SLK), in which the only possible phosphorylated residue is Ser859 (Figs 4c and d).

Fig. 4.

Identification of phosphorylation sites of m7CTX and m4CTX. (a) and (c) Total ion current trace of precursor ion scanning LC-MS experiment for m7CTX and m4CTX tryptic peptides. The mass spectrums of phosphopeptides present in the tryptic digests are shown in the inserts. The only phosphopeptides S(PO3H)FK from m7CTX corresponds to residues 20–22 (SFK) in m7CTX and Ser862 in mGluR7 cDNA sequence, and that of m4CTX, S(PO3H)LK, corresponds to residues 18–20 in m4CTX and Ser859 in mGluR4 cDNA sequence. (b) and (d) The UV traces of the same runs. T5-PO3H stands for the phosphorylated peptide (residues 20–22 (S(PO3H)FK) in m7CTX or residues 18–20 (S(PO3H)LK) in m4CTX) which elutes very early as the back shoulder of the solvent peak.

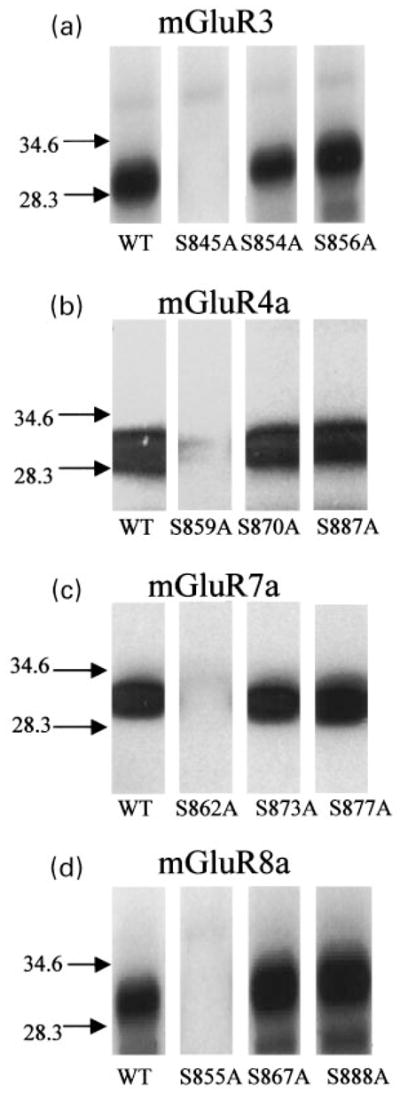

Mutation analysis confirmed the results of phosphopeptide analysis and identified a single serine residue as the phosphorylation site by PKA for each mGluR subtype tested. Single mutations of Ser859 and Ser855 to alanine (S859A and S855A) dramatically reduced phosphorylation of the GST fusion proteins of m4CTX and m8CTX, respectively, while other serine to alanine mutations had no effect (Figs 5b and d), indicating the phosphorylation sites in m4CTX and m8CTX are the single PKA consensus sites in their C-terminal tails (Ser859 and Ser855, respectively). The mutation of Ser862 to alanine (S862A) dramatically reduced phosphorylation of the GST fusion protein of m7CTX, while other serine to alanine mutations (S873A and S877A) had no effect (Fig. 5c). Although both Ser862 and Ser877 in mGluR7 are PKA consensus sites, it is apparent that only Ser862 is phosphorylated by PKA. Similarly, we showed previously that between the two (Ser843 and Ser837) PKA consensus sites in mGluR2 C-terminal tail, only one (Ser843) is the phosphorylation site by PKA. For the other group II mGluR subtype, mGluR3, mutation of the only PKA consensus site (S845A) dramatically reduced phosphorylation of the GST fusion protein of m3CTX, while mutations of other serines had no effect (Fig. 5a). In summary, PKA phosphorylates all tested group II and III mGluRs at single serine residues on their intracellular C-terminal tails.

Fig. 5.

Identification of PKA phosphorylation sites with mutation analysis. In vitro phosphorylation of mGluR C-terminus fusion protein with site-directed mutagenesis showing a single serine residue as the phosphorylation site for each mGluR tested, including Ser845 for mGluR3 (a), Ser859 for mGluR4 (b), Ser862 for mGluR7 (c), and S355 for mGluR8 (d). Each autoradiograph is representative of 3 independent experiments, showing PKA-induced phosphorylation of GST fusion proteins.

Forskolin reduces Group III mGluR function at multiple hippocampal synapses

For mGluR2, PKA-induced phosphorylation of Ser843 inhibits receptor function in in vitro recombinant systems. Additionally, PKA activation with the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin inhibits group II mGluR (most likely mGluR2)-mediated effects at the MPP-DG synapse (Schaffhauser et al. 2000). Coupled with the present findings, this raises the possibility that PKA may also inhibit the function of presynaptic group III mGluRs.

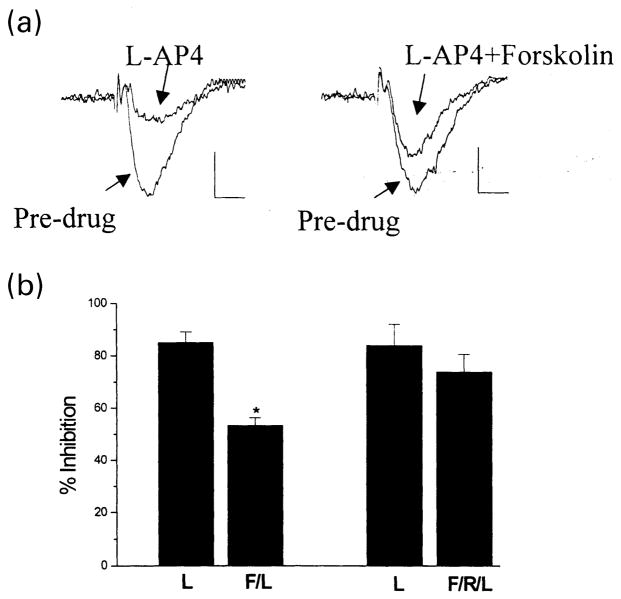

Previous studies indicated that activation of mGluR7 reduces transmission at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 (SC-CA1) synapses (Gereau and Conn 1995; Bradley et al. 1996, 1998; Shigemoto et al. 1997). Therefore, we determined the effect of forskolin on mGluR7 function at the SC-CA1 synapse. Consistent with previous results, the selective group III mGluR agonist, L-AP4 (1 mM), induced a reversible depression of field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) at the SC-CA1 synapses (Fig. 6a). The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (50 μM) markedly reduced the inhibitory effect of L-AP4 at the SC-CA1 synapse (Fig. 6a,b). If forskolin-induced inhibition of the response to L-AP4 is mediated by activation of PKA rather than a non-specific action of the drug, a PKA inhibitor should block this response. Consistent with this, coapplication of Rp-cAMPs (100 μM), a selective PKA inhibitor, essentially blocked the effect of forskolin (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Effect of PKA activation on mGluR7 function at the SC-CA1 synapses in the rat hippocampus. (a) 1 mM L-AP4 suppressed field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP) dramatically; this mGluR7-mediated effect was inhibited by coapplication of 50 μM forskolin. Calibration: 0.2 mV, 10 ms. (b) Bar graph showing the mean effect of L-AP4 (L) with or without forskolin on fEPSP. The forskolin (F) effect was blocked by a selective inhibitor of PKA, Rp-cAMP (R). n = 4 for each column; error bars show the standard errors of the means; Student’s t-test; *different from L-AP4 alone, p < 0.05.

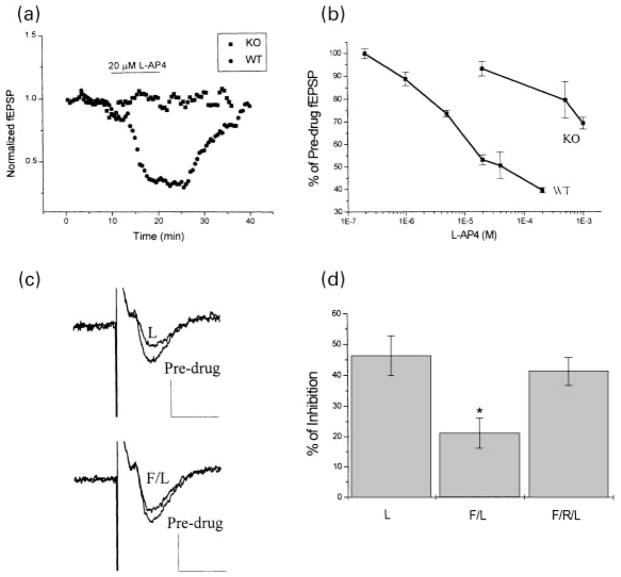

Application of L-AP4 inhibits synaptic transmission at the LPP-DG synapses, and it has been suggested that mGluR8 mediates this effect (Johansen et al. 1995; Macek et al. 1996; Dietrich et al. 1997; Saugstad et al. 1997; Shigemoto et al. 1997). To rigorously test this hypothesis, we generated mice in which the mGluR8 gene was inactivated by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells (Duvoisin et al. 1999; Zhang and Duvoisin, unpublished observations). The L-AP4-induced effect at LPP-DG synapses was examined in both mGluR8-deficient and wild-type mice. Application of 20 μM L-AP4 inhibited 50% of fEPSP slope at the LPP-DG synapses in hippocampal slices from wild-type mice (Fig. 7a), but had no significant effect in slices from mGluR8-deficient mice (Figs 7a and b). However, L-AP4 did induce a slight inhibition of transmission at this synapse at higher concentrations (mM range) in these animals as shown by the dose–response curve (Fig. 7b). This effect could be mediated by a low affinity group III mGluR, for example mGluR7. In wild-type animals this inhibition may be masked by that produced by mGluR8. Alternatively, mGluR7 expression may be up-regulated in mGluR8-deficient mice.

Fig. 7.

Effect of PKA activation on mGluR8 function at the LPP-DG synapses. (a) and (b) fEPSP recordings at the lateral perforant (LPP-DG) synapse from mGluR8-deficient (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice. L-AP4 (20 μM) induced suppression of fEPSP at these synapses in wild-type mice, but had no effect in mGluR8-deficient mice (a). Dose–response curves of L-AP4-induced suppression of fEPSP in both wild-type and mGluR8-deficient mice are shown in (b) (n = 3–4 for each point). (c) and (d) 50 μM forskolin (F) inhibited 20 μM L-AP4 (L)-induced suppression of fEPSP at the LPP-DG synapses in the rat hippocampus, as shown by sample traces of fEPSP recording (c) and a bar graph (d) showing the mean effect across 3 slices. The forskolin effect was blocked by coapplication with 100 μM Rp-cAMPs (R). Student’s t-test; *different from L-AP4 alone, p < 0.05.

The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (50 μM) also markedly reduced the inhibitory effect of L-AP4 at the LPP-DG synapses (Figs 7c and d), and the forskolin effect was blocked by Rp-cAMPs (100 μM). In other studies, we have also found that forskolin inhibits L-AP4-induced suppression of GABA-mediated inhibitory synaptic transmission in the substantia nigra, where mGluR4 or mGluR7 could be the presynaptic mGluR present (Wittmann et al., unpublished findings). Taken together with our previous study of mGluR2, these data suggest that PKA-induced inhibition of presynaptic mGluR function is a general phenomenon that applies to group II and multiple group III mGluRs and can be seen at a variety of central synapses.

Isoproterenol reduces mGluR2 and mGluR7 function, but not mGluR8 function at hippocampal synapses

The results presented above, coupled with our previous study (Schaffhauser et al. 2000), suggest that PKA-induced phosphorylation and inhibition of presynaptic mGluRs is a general mechanism by which both group II and group III mGluR function can be regulated. However, it is not yet known whether activation of receptors that are coupled to Gs protein and adenylyl cyclase/PKA activation, such as β-adrenergic receptors, can elicit this response.

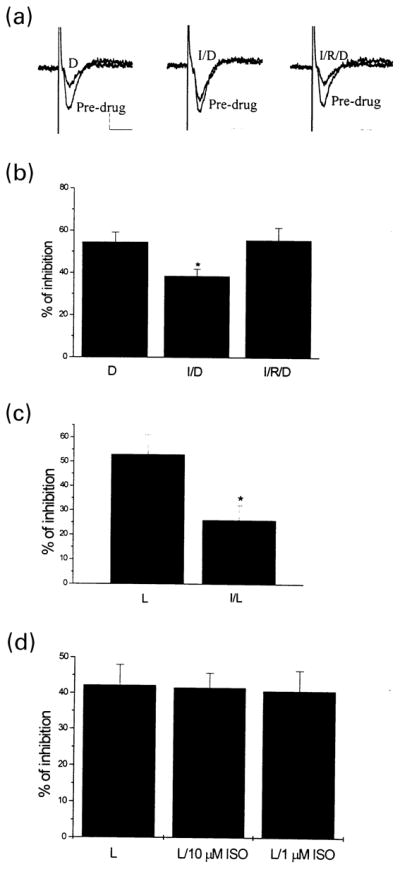

To determine the effect of β-adrenergic receptor activation on mGluR2 function, we examined the effect of a selective group II mGluR agonist (DCG-IV) on fEPSPs at the MPP-DG synapses in the absence and presence of the selective β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (ISO). DCG-IV (1 μM) induced a reversible depression of fEPSPs at the MPP-DG synapses (Fig. 8a). The response to DCG-IV was significantly reduced when ISO (1 μM) was applied for 10 min prior to DCG-IV application (Figs 8a and b). The predominant signaling pathway employed by β–adrenergic receptors is activation of adenylyl cyclase and subsequent activation of PKA. Consistent with the hypothesis that this response is mediated by activation of this signaling pathway, the effect of ISO was completely blocked by perfusion with Rp-cAMPs (100 μM), a selective inhibitor of PKA (Figs 8a and b). Similarly, ISO inhibited L-AP4-induced suppression of fEPSPs at SC-CA1 synapses (Fig. 8c), which is an mGluR7-mediated response. These results suggest that activation of endogenous Gs-coupled neurotransmitter receptors induces a PKA-dependent inhibition of presynaptic mGluR function in the hippocampus. We next tested this effect on mGluR8 function at the LPP-DG synapses. ISO (1–10 μM) did not affect the ability of L-AP4 to suppress fEPSPs at these synapses (Fig. 8d). Thus, while the ability of PKA to inhibit presynaptic mGluR function is relatively widespread, the specific Gs-coupled receptors that can elicit this effect are likely to be synapse-specific.

Fig. 8.

Effect of isoproterenol on presynaptic mGluRs in the rat hippocampus. (a) and (b) 1 μM ISO (I) inhibited 1 μM DCG-IV (D)-induced depression of fEPSP at MPP-DG synapses, as shown by sample traces of recording (a) and a bar graph expressing the mean effect across four slices (b). In the presence of 100 μM Rp-cAMPs (R), Iso failed to reduce DCG-IV-induced depression of fEPSP (a) and (b). *Different from DCG-IV alone; Student’s t-test; p < 0.05. (c) 1 μM ISO (I) inhibited 1 mM L-AP4 (L)-induced suppression of fEPSPs at SC-CA1 synapses. Student’s t-test; *different from L-AP4 alone, p < 0.05. (d) At LPP-DG synapses, 1 or 10 μM ISO did not affect the ability of 20 μM L-AP4 (L) to suppress fEPSP at these synapses. n = 3 for each column.

Discussion

The present study, combined with a previous report (Schaffhauser et al. 2000), suggests that each of the group II and group III mGluR subtypes is phosphorylated by PKA at a single serine residue in the C-terminal region. Furthermore, functional studies of the effect of PKA activation on presynaptic responses to mGluR activation suggest that activation of PKA inhibits the function of both group II and group III mGluRs. We previously showed that PKA-induced phosphorylation inhibits mGluR2 signaling by inhibiting coupling of the receptor to GTP binding proteins (Schaffhauser et al. 2000). The present studies raise the possibility that PKA inhibits the function of multiple mGluR subtypes by a similar mechanism.

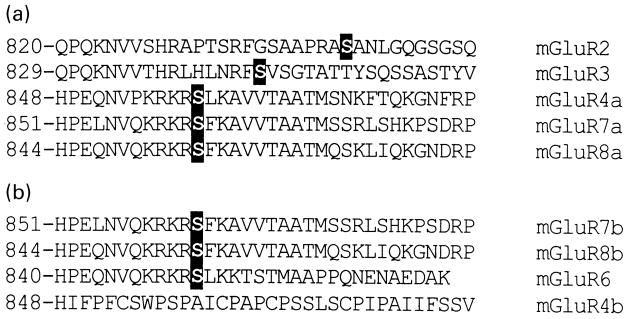

As illustrated in Fig. 9(a), sequence alignment reveals that all of the group III mGluR subtypes have a high level of sequence homology in the region of the PKA phosphorylation site. Interestingly, the serine residues that are phosphorylated on each of these receptors are highly conserved across all tested group III mGluRs. This site is not strictly conserved in group II mGluRs. However, the PKA phosphorylation sites on mGluR2 and mGluR3 are in the same region of the C-terminal tail of these receptors (Fig. 9a). The conserved phosphorylation sites on group III mGluR C-terminal tails are in the KRXXS motif, while the phosphorylation sites on group II mGluR C-terminal tails are in the RXS motif. Presumably, the serine in a KRXXS motif is a better PKA phosphorylation site than that in a RXS motif, which could explain the enhanced in vitro phosphorylation of group III mGluRs vs. group II mGluRs (Fig. 2). This conserved PKA site is also present in mGluR6 and all other alternatively spliced forms of group III mGluRs except for mGluR4b (Fig. 9b). The presence of consensus PKA sites in C-terminal tails of mGluR1a and both mGluR5 splice variants (5a and 5b) suggests that group I mGluRs may be similarly regulated by PKA activity. However, the C-terminal tails of mGluR1 splice forms 1b, 1c and 1d differ significantly from mGluR1a and do not contain consensus PKA sites. These observations indicate that PKA activity may be an important regulatory feature across the family of mGluRs. However, for mGluR4 and mGluR1, alternate splicing may be an important aspect in determining the role that PKA plays in regulating these receptors.

Fig. 9.

Sequence alignments of a C-terminal region in group II and group III mGluRs. The region shown is directly downstream of the C-terminus of the seventh transmembrane domain. Sequences further downstream in the mGluRs listed here contain no PKA consensus sites, and were not shown. (a) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of tested group II and III mGluRs showing single serine residues as PKA phosphorylation sites (in black box). (b) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of non-tested group III mGluRs showing the PKA consensus sites (in black box). Note that sequences shown for mGluR7b and 8b are the same as for mGluR7a and 8a, respectively, because they use splice sites downstream of this region.

It is important to note that Nakajima et al. (1999) recently reported that PKA does not phosphorylate a GST fusion protein of the C terminal tail of mGluR7. However, the major focus of that report was phosphorylation of mGluR7 by PKC rather than PKA. Thus the discrepancy between these two studies may be caused by the failure to optimize experimental conditions for PKA activities in the previous study.

In recent years it has become clear that PKA plays an important role in the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) at a variety of glutamatergic synapses (Frey et al. 1993; Huang et al. 1994; Weisskopf et al. 1994; Qi et al. 1996; Salin et al. 1996; Linden and Ahn 1999). Furthermore, recent studies suggest that presynaptic mGluRs are important for the induction of long-term depression (LTD) at multiple synapses, including the hippocampal synapses included in this study (Manahan-Vaughan 1997, 1998, 2000). While speculative, it is conceivable that one function of PKA-induced phosphorylation of presynaptic mGluRs could be to reduce mGluR-induced activities that might oppose the induction of LTP. This possibility is especially interesting in light of the finding that activation of β-adrenergic receptors induces a PKA-dependent inhibition of presynaptic mGluR function at SC-CA1 and MPP-DG synapses. Previous studies suggest that β-adrenergic receptor activation plays an important role in the induction of acute and long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission at multiple hippocampal synapses (Stanton and Sarvey 1987; Hopkins and Johnston 1988; Dahl and Sarvey 1989; Dunwiddie et al. 1992; Gereau and Conn 1994a,b; Huang and Kandel 1996). It is tempting to speculate that β-adrenergic receptor-induced disruption of the inhibitory actions of presynaptic mGluRs contributes to the ability of β-adrenergic receptors to enhance transmission at these synapses. Interestingly, β-adrenergic receptor activation also induces an increase in NMDA receptor responses in hippocampal neurons (Raman et al. 1996). Thus, β-adrenergic receptors may have opposite modulatory actions on presynaptic and postsynaptic glutamate receptors to bring about a net increase in glutamatergic transmission.

Although the activation of β-adrenergic receptors by ISO inhibits mGluR7 function at MPP-DG synapses, in this study it had no effect on mGluR8 function at LPP-DG synapses. A similar pathway specificity of ISO-induced plasticity in the dentate gyrus has been reported by Dahl and Sarvey (1989) and Pelletier et al. (1994) who found that isoproterenol induced a long-lasting potentiation (LLP) at MPP-DG synapses, and a long-lasting depression (LLD) at LPP-DG synapses. Stimulation of noradrenergic inputs to the hippocampus from the locus coeruleus in vivo was also found to be pathway specific (Babstock and Harley 1993). How this specificity arises is unknown, as there is no evidence for a pathway-specific localization of β-adrenergic receptors in the dentate gyrus (Rainbow et al. 1984; Booze et al. 1993). In the future, it will be interesting to directly determine whether the presynaptic mGluRs at these different hippocampal synapses are differentially phosphorylated in response to β-adrenergic receptor activation. Also, it will be of interest to determine whether LTP-inducing stimuli lead to a phosphorylation of presynaptic mGluRs and transiently decrease presynaptic mGluR function.

We and others have shown that activation of PKC inhibits the function of multiple presynaptic mGluRs at a wide variety of glutamatergic synapses in a manner similar to the effect of PKA reported here. These include mGluR7 at SC-CA1 synapses, mGluR8 at the LPP-DG synapses, and mGluR2 at MPP-DG, corticostriatal, and mossy fiber synapses (Macek et al. 1998; Swartz et al. 1993; Kamiya and Yamamoto 1997). Thus, PKC and PKA have similar widespread actions on multiple presynaptic mGluR subtypes. As PKC phosphorylates mGluR7 at the same site (Ser862) as PKA (Airas et al. 2001), it is very likely that both PKA and PKC regulate group III mGluRs through direct receptor phosphorylation at the same conserved site in their C-terminal tails. Interestingly, activation of A3 adenosine receptors (Macek et al. 1998) and β-adrenergic receptors (this study) inhibit mGluR7 function at the SC-CA1 synapses, through PKC- and PKA-dependent mechanisms, respectively. Thus, presynaptic mGluRs can be inhibited by several mechanisms involving different presynaptic receptors coupled to either Gs or Gq signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Miklos Toth for help with generating the mGluR8-deficient animals, and Ms Olga Stuchlik for purification of mGluR proteins. This study is supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants NS313373, NS 34876, NS 36755 (PJC), NIH grant EY09534 (RMD), NIH-NCRR shared instrumentation grants 02878 and 13948 (JP), and the Alzheimer’s Association grant PRG98021 and NIMH grant R01–521635 (JAS).

Abbreviations used

- aCSF

artificial cerebral spinal fluid

- DCG-IV

(2S,2′R,3′R)-2-(2′,3′-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine

- DHPG

3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry

- fEPSP

field excitatory postsynaptic potential

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- ISO

isoproterenol

- L-AP4

(L)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- LPP-DG

lateral perforant path-dentate gyrus

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MPP-DG

medial perforant path-dentate gyrus

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKI

PKA inhibitor

- Rp-cAMP

Rp-isomer of cAMP

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

References

- Airas JM, Betz H, El Far O. PKC phosphorylation of a conserved serine residue in the C-terminus of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits calmodulin binding. FEBS Lett. 2001;494:60–63. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babstock DM, Harley CW. Lateral olfactory tract input to dentate gyrus is depressed by prior noradrenergic activation using nucleus paragigantocellularis stimulation. Brain Res. 1993;629:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booze RM, -Crisostomo EA, Davis JN. Beta-adrenergic receptors in the hippocampal and retrohippocampal regions of rats and guinea pigs: autoradiographic and immunohistochemical studies. Synapse. 1993;13:206–214. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Levey AI, Hersch SM, Conn PJ. Immunocytochemical localization of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the hippocampus with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2044–2056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02044.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Rees HD, Yi H, Levey AI, Conn PJ. Distribution and developmental regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7a in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1998;71:636–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Standaert DG, Rhodes KJ, Rees HD, Testa CM, Levey AI, Conn PJ. Immunohistochemical localization of subtype 4a metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat and mouse basal ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 1999;407:33–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti C, Restituito S, Rimland JM, Brabet I, Corsi M, Pin JP, Ferraguti F. Cloning and characterization of alternative mRNA forms for the rat metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR7 and mGluR8. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3629–3641. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl D, Sarvey JM. Norepinephrine induces pathway-specific long-lasting potentiation and depression in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4776–4780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich D, Beck H, Kral T, Clusmann H, Elger CE, Schramm J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate synaptic transmission in the perforant path: pharmacology and localization of two distinct receptors. Brain Res. 1997;767:220–227. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Taylor M, Heginbotham LR, Proctor WR. Long-term increases in excitability in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus induced by beta-adrenergic stimulation: possible mediation by cAMP. J Neurosci. 1992;12:506–517. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00506.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin RM, Zhang C, Maltseva OV, Berntson A, Taylor RW. Functional properties of retinal cells in mGluR8-deficient transgenic mice. Neuropharmcology. 1999;38:A14. [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Huang YY, Kandel ER. Effects of cAMP simulate a late stage of LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Science. 1993;260:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.8389057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau RW, Conn PJ. Presynaptic enhancement of excitatory synaptic transmission by beta-adrenergic receptor activation. J Neurophysiol. 1994a;72:1438–1442. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.3.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau RW, Conn PJ. A cyclic AMP-dependent form of associative synaptic plasticity induced by coactivation of beta-adrenergic receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1994b;14:3310–3318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03310.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau RW, Conn PJ. Multiple presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal area CA1. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6879–6889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WF, Johnston D. Noradrenergic enhancement of long-term potentiation at mossy fiber synapses in the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:667–687. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.2.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Li XC, Kandel ER. cAMP contributes to mossy fiber LTP by initiating both a covalently mediated early phase and macromolecular synthesis-dependent late phase. Cell. 1994;79:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel ER. Modulation of both the early and the late phase of mossy fiber LTP by the activation of beta-adrenergic receptors. Neuron. 1996;16:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen PA, Chase LA, Sinor AD, Koerner JF, Johnson RL, Robinson MB. Type 4a metabotropic glutamate receptor: identification of new potent agonists and from the L-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutanoic acid-sensitive receptor in the lateral perforant pathway in rats. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:140–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle JS, Cotman CW. Adenosine, L-AP4, and baclofen modulation of paired-pulse potentiation in the dentate gyrus: interstimulus interval-dependent pharmacology. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94:97–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00230473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Yamamoto C. Phorbol ester and forskolin suppress the presynaptic inhibitory action of group II metabotropic glutamate receptor at rat hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuroscience. 1997;80:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DJ, Ahn S. Activation of presynaptic cAMP-dependent protein kinase is required for induction of cerebellar long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10221–10227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10221.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Toth K, McBain CJ. Target-specific expression of presynaptic mossy fiber plasticity. Science. 1998;279:1368–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macek TA, Winder DG, Gereau RW, Ladd CO, Conn PJ. Differential involvement of group II and group III mGluRs as autoreceptors at lateral and medial perforant path synapses. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3798–3806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macek TA, Schaffhauser H, Conn PJ. Protein kinase C and A3 adenosine receptor activation inhibit presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors and uncouples the receptor from GTP-binding proteins. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6138–6146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06138.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D. Group 1 and 2 metabotropic glutamate receptors play differential roles in hippocampal long-term depression and long-term potentiation in freely moving rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3303–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03303.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D. Priming of group 2 metabotropic glutamate receptors facilitates induction of long-term depression in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1459–1464. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D. Group III metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate long-term depression in the hippocampal CA1 region of two rat strains in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1952–1958. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary S, Stephan D, Gomeza J, Bockaert J, Pruss RM, Pin JP. The rat mGlu1d receptor splice variant shares functional properties with the other short isoforms of mGlu1 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;335:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakami R, Katsuki F, Yamamoto T, Nakamura K, Sugiyama H. Molecular cloning and the functional expression of two isoforms of human metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:1136–1143. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Yamamoto T, Nakayama T, Nakanishi S. A relationship between protein kinase C phosphorylation and calmodulin binding to the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27573–27577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier MR, Kirkby RD, Jones SJ, Corcoran ME. Pathway specificity of noradrenergic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 1994;4:181–188. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Waeber C, Prezeau L, Bockaert J, Heinemann SF. Alternative splicing generates metabotropic glutamate receptors inducing different patterns of calcium release in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10331–10335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Zhuo M, Skalhegg BS, Brandon EP, Kandel ER, McKnight GS, Idzerda RL. Impaired hippocampal plasticity in mice lacking the Cbeta1 catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1571–1576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow TC, Parsons B, Wolfe BB. Quantitative autoradiography of beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptors in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1585–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Tong G, Jahr CE. Beta-adrenergic regulation of synaptic NMDA receptors by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron. 1996;16:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin PA, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Cyclic AMP mediates a presynaptic form of LTP at cerebellar parallel fiber synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:797–803. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad JA, Kinizie JM, Shinohara MM, Segerson TP, Westbrook GL. Cloning and expression of rat metabotropic glutamate receptor 8 reveals a distinct pharmacological profile. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:119–125. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffhauser H, Cai Z, Hubalek F, Macek TA, Pohl J, Murphy TJ, Conn PJ. cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits mGluR2 coupling to G-proteins by direct receptor phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5663–5670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05663.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Wada E, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Takada M, Flor PJ, Neki A, Abe T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7503–7522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton PK, Sarvey JM. Norepinephrine regulates long-term potentiation of both the population spike and dendritic EPSP in hippocampal dentate gyrus. Brain Res Bull. 1987;18:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ, Merritt A, Bean BP, Lovinger DM. Protein kinase C modulates glutamate receptor inhibition of Ca2+ channels and synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;361:165–168. doi: 10.1038/361165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe Y, Masu M, Ishii T, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S. A family of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90118-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen C, Pekhletski R, Haldeman B, Gilbert TA, O’Hara P, Hampson DR. Cloning and characterization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR4b. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Castillo PE, Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Mediation of hippocampal mossy fiber long-term potentiation by cyclic AMP. Science. 1994;265:1878–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.7916482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]