Abstract

Background

Individuals ≥80 years of age represent an increasing proportion of colon cancer diagnoses. Selecting these patients for elective surgery is challenging due to diminished overall health, functional decline, and limited data to guide decisions. The objective was to identify overall health measures that are predictive of poor survival after elective surgery in these oldest-old colon cancer patients.

Methods

Medicare beneficiaries ≥80 years who underwent elective colectomy for stage I-III colon cancer from 1992-2005 were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results(SEER)-Medicare database. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis determined 90-day and 1-year overall survival. Multivariable logistic regression assessed factors associated with short-term post-operative survival.

Results

Overall survival for the 12,979 oldest-old patients undergoing elective colectomy for colon cancer was 93.4% and 85.7%, at 90-days and 1-year. Older age, male gender, frailty, increased hospitalizations in prior year, and dementia were most strongly associated with decreased survival. In addition, AJCC stage III (versus stage I) disease and widowed (versus married) were highly associated with decreased survival at 1-year. Although only 4.4% of patients were considered frail, this had the strongest association with mortality, with an odds ratio of 8.4 (95% confidence interval 6.4-11.1).

Discussion

Although most oldest-old colon cancer patients do well after elective colectomy, a significant proportion (6.6%) dies by post-operative day 90 and frailty is the strongest predictor. The ability to identify frailty through billing claims is intriguing and suggests the potential to prospectively identify, through the electronic medical record, patients at highest risk of decreased survival.

INTRODUCTION

The United States population is aging, with much of the growth occurring in individuals ≥80 years of age.1 These changes in the nation's demographics have had a significant impact on cancer care. This is especially true for colon cancer, where the incident rate increases with age, to a peak of over 350 cases/100,000 individuals ≥80 years of age.2 Surgical decision-making for these “oldest-old” patients is unique. Limited evidence exists to inform colon cancer treatment decisions in the oldest-old adults, as this population has been underrepresented in cancer clinical trials and excluded from clinical practice guidelines.3 Additionally, many oldest-old adults are at increased perioperative risk due to diminished overall health status and functional decline. Balancing these factors makes oncologic treatment decision-making for these patients challenging.

Overall health status and functional decline can be measured through a number of distinct, but related, domains and a growing body of literature suggests that these domains are highly associated with surgical outcomes in elderly patients.4 Assessable domains include overall healthcare utilization, comorbidity, disability (difficulty or dependence in one or more activities of daily living), and frailty. Frailty in particular has been associated with a number of surgical post-operative outcomes, including increased hospital and post-discharge costs,5 post-operative length of stay,6 complications,6-9 likelihood of requiring institutionalization after discharge,6,10,11 and 6 month mortality.11 Frailty is characterized by decreased physiologic reserve and resistance to stressors, which occurs as a result of physiologic multi-system decline.12 Importantly, by this definition, patients may be frail without having a life-threatening illness.13

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for colon cancer. For patients ≥80 years of age, a significant percentage of surgeries (20-45%) occur during an urgent or emergent admission, and are associated with increased complications and decreased survival.14-17 Despite the increased perioperative risk associated with surgery under urgent or emergent conditions, these patients represent less of a decision-making challenge for surgeons, as the acuity and severity of the presenting symptoms often alters the risk-benefit ratio for even the highest-risk patient. More challenging is that subset of patients who present electively for consideration of colectomy for cancer. Although most of these patients do well after surgery, clinical practice suggests that there is a subset of older patients who do extremely poorly after an elective colectomy. Identification of these patients pre-operatively would enhance the quality of informed consent and aid in surgical decision-making. Therefore, we sought to identify pre-operatively recognizable measures of overall health that are predictive of poor short-term survival after elective surgery in the oldest-old colon cancer patients.

METHODS

This study was reviewed by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board and granted a waiver of consent.

Data source

The linked Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database was used to identify patients undergoing colon cancer surgery from 1992-2005. The SEER-Medicare data resource has been previously described by our group18-20 and others,21,22 and is an established resource for studying longitudinal cancer in elderly patients.

Patient selection

Our primary cohort of interest was Medicare-enrolled patients aged 80 years and older diagnosed with stage I-III primary colon adenocarcinoma within a SEER region between 1992 and 2005. However, data for patients 65-79 years of age was also examined to provide a comparative group against which outcomes for the oldest-old colon cancer patients could be grounded. SEER anatomic site (18.0-18.9, 19.9), and histology (8140-8417, 8210-11, 8220-21, 8260-63, 8480-81, 8490) codes were used to identify colon cancer patients. Patients were included in the study if they underwent colectomy (ICD-9 procedure codes: 45.7X and 45.8X) during an elective hospital admission (defined using admission type variable within the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File). Patients undergoing surgery more than 90-days after diagnosis were excluded, as these operations were less likely to be of curative intent. Continuous enrollment in Medicare Part A and B was required for the 3-years preceding diagnosis through the 3-years following discharge, death, or December 31, 2005 (whichever came first) to allow ascertainment of comorbidities and survival. Patients were excluded if they were enrolled in a Health Maintenance Organization during the same time period. Patients were also excluded if they were diagnosed with another malignancy one year before or after the date of colon cancer diagnosis, or if their first diagnosis of colon cancer was made after death (i.e., on autopsy or death certificate). From an initial cohort of 42,873 stage I-III colon cancer patients ≥80 years of age, the following patients were sequentially excluded: stage IV disease or unknown stage (n=11,122), discontinuous Medicare Part A and Part B coverage (n=1,012), another cancer within one year of colon cancer diagnosis (n=2,968), and surgery during a non-elective admission (n=14,792). The final sample size was 12,979 patients.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome measures for this study was 90-day overall survival. This was defined using dates of death recorded in the SEER Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File (PEDSF) according to Social Security Administration data. Additionally, we examined 1-year overall survival, length of stay, discharge destination, 30-day readmission rates (readmission to any acute care hospital), and receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (defined as any claim for chemotherapy within 9 months of surgery [ICD-9 V58.1, V66.2, V67.2, E9331, 99.25; CPT 96400-96599; Health Care Common Procedure Coding System codes Q0083-Q0085, E0781, C8953-5, S9329-31, G0355-63; J0640, J8520, J8521, Q0177, J8510, J8530-J8999, J9000-J9999; Revenue center codes 0331, 0332-, 0335 ).19,23,24

Patient-related variables

Basic demographics, including date of birth, gender, race/ethnicity, and marital status, were obtained from SEER data. Socioeconomic status was assessed using census tract median level of household income and median level of education. Geographic region was represented by SEER registry. Tumor stage was assessed using American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging.

Patients’ overall health was assessed by a number of means. Health care utilization was assessed by recording the number of emergency room and hospital admissions in the year prior to diagnosis. Specific comorbidities were identified, as described by Elixhauser, et al.25 Dementia was identified using a separate, validated algorithm given the importance of dementia in treatment-decision-making for older adults (utilizing ICD-9 codes 331.0-331.1, 331.11, 331.19, 331.7, 290.0, 290.10-290.13, 290.20-290.21, 290.3, 290.40-290.43, 294.0, 294.1, 294.10, 294.11, 294,8, and 797).26 Disability was indirectly assessed by examining home oxygen use and mobility. Home oxygen was recorded if patients had 2 codes related to home oxygen usage (DME A7017) in the 3 years prior to diagnosis. Mobility was assessed by examining claims for ambulatory assist devices in the 3-years prior to diagnosis (assessment for device: 97755, 97542; cane: E0100, E0105; crutch: E0110-E0017; walker: E0130, E0135, E0140-E0141, E0143-E0144, E0147-E0149; wheelchair: K0001-K0007, E0983, E0984, E1210-E1213, E2368-E2370, K0010-K0012, K0014, K0800-K0899). Patient frailty was assessed as defined by the John Hopkins’ Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) case-mix system. This validated measure of frailty was developed to be used specifically on administrative data and assesses frailty by the presence of 11 conditions (e.g., difficulty walking, weight loss, frequent falls, malnutrition, impaired vision, decubitus ulcer, incontinence, etc.).27 Dementia is one of the 11 conditions included in the ACG definition of frailty; however, it was excluded from the frailty definition in this study as it was being incorporated into the model as a unique variable (described above). Patients having ICD-9 diagnosis codes for any of these conditions were considered to be frail; of the “frail” patients, 80% were considered to be frail based on a single criteria. The most common single codes were difficulty walking (56%), weight loss (24%), and decubitus ulcers (12%); the remaining codes occurred most frequently in combination.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of patient characteristics were generated, and differences between the cohort ≥80 years of age and <80 years of age were compared using χ2 tests and two sample t-tests. Short-term outcomes (length of stay, discharge destination, and hospital readmission rates) were summarized. χ2 tests and two sample t-tests were used as appropriate to compare outcomes between patients <80 and ≥80 years of age. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to obtain 90-day and 1-year overall survival estimates and log-rank tests were used to compare survival outcomes between patients <80 and ≥80 years of age. Separate logistic regression models were used to evaluate 90-day and 1-year mortality (binary yes/no variable). These multivariable logistic models adjusted for a variety of factors related to patient demographics, tumor, and overall health status.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics of the 12,979 eligible patients ≥80 years of age are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the oldest-old cohort was 84.4 years, and the majority were female (61.4%), white (90.1%), and unmarried (56.3%). Localized (node-negative) colon cancer was present in 72.7% of our cohort. Characteristics of the 19,451 patients <80 years of age are included for comparison, and as would be expected, significant differences existed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of colon cancer patients undergoing elective colon resection

| Characteristic | N or Median (% or range) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥80 years of age (N=12,979) | <80 years of age (N=19,451) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 84.4 (3.7) | 73.9 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Male | 5,003 (39%) | 8,904 (46%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 11,688 (90%) | 16,658 (86%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 538 (4.2%) | 1,200 (6.2%) | |

| Other | 753 (5.8%) | 1,593 (8.2%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 5,266 (41%) | 11,839 (61%) | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 6,173 (48%) | 4,718 (24%) | |

| Single, separated, divorced | 1,128 (8.7%) | 2,312 (12%) | |

| AJCC Stage | |||

| 1 | 3,556 (27%) | 6,053 (31%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 5,884 (45%) | 7,662 (39%) | |

| 3 | 3,539 (27%) | 5,736 (29%) | |

| Overall Health Status | |||

| Health Care Utilization | |||

| Number of hospital admissions in prior year, median | 1 (1-9) | 1 (1-15) | <0.001 |

| Number of ER visits in prior year, median | 2 (1-83) | 2 (1-151) | 0.005 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Dementia | 114 (0.9%) | 34 (0.2%) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4,644 (36%) | 4,140 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Valvular disease | 1,932 (15%) | 2,134 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 9,897 (76%) | 14,425 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3,845 (30%) | 3,856 (20%) | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 423 (3.3%) | 489 (2.5%) | <0.001 |

| Other neurologic disorders | 1,681 (13%) | 1,742 (9.0%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 3,327 (26%) | 5,009 (26%) | 0.81 |

| Diabetes (uncomplicated) | 1,942 (15%) | 3,450 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (with complications) | 1,103 (8.5%) | 2,116 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 718 (5.5%) | 1,024 (5.3%) | 0.30 |

| Weight loss | 837 (6.5%) | 897 (4.6%) | <0.001 |

| Electrolyte abnormalities | 2,743 (21%) | 3,590 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1,385 (11%) | 1,729 (8.9%) | <0.001 |

| Disability | |||

| Home Oxygen | 297 (2.3%) | 383 (2.0%) | 0.05 |

| Mobility assist device | |||

| No assessment | 11,290 (87%) | 18,192 (94%) | <0.001 |

| Crutch/cane | 1,207 (9.3%) | 924 (4.8%) | |

| Wheelchair | 482 (3.7%) | 335 (1.7%) | |

| Frail | 566 (4.4%) | 289 (1.5%) | <0.001 |

SD, Standard Deviation; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, Emergency Room

The oldest-old patients undergoing elective colectomy were relatively healthy, with few hospital admissions in the prior year (mean 1.44), and few patients requiring home oxygen (2.3%) or a wheelchair (3.7%). The most common comorbidities included hypertension (76.3%), congestive heart failure (35.8%), peripheral vascular disease (29.6%), chronic pulmonary disease (25.6%), and diabetes (23.5%). Few patients met criteria for dementia (0.9%) or frailty (4.4%).

Short-term outcomes for our oldest-old patient cohort were generally good compared to that of “younger” patients (Table 2). Median length of stay was 9 (2-165) days. The majority of patients were discharged home, with 22.1% being discharged to a skilled nursing facility. Readmission within 30-days of discharge occurred for 10.9% of patients. Only 14% of patients ≥80 years of age received chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Short term outcomes of colon cancer patients undergoing elective colon resection

| N or Median (% or range) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥80 years of age (N=12,979) | <80 years of age (N=19,451) | ||

| Median length of stay (days) | 9 (2-165) | 8 (1-132) | <0.001 |

| Discharge home | 9,472 (73%) | 17,790 (92%) | <0.001 |

| Readmission within 30 days | 1,408 (11%) | 1,757 (9.0%) | <0.001 |

| Receipt of chemotherapy | 1,834 (14%) | 6,531 (34%) | <0.001 |

| Proportion alive at 90-days | 93.4% | 97.6% | <0.001 |

| Proportion alive at 1-year | 85.7% | 93.5% | <0.001 |

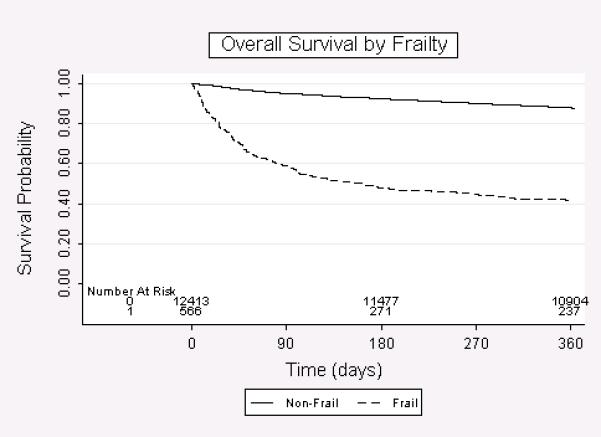

Ninety-day and 1-year overall survival for our patient population was 93.4% and 85.7%, respectively (Figure 1), compared to 97.6% and 93.5% for “younger” patients. Of those oldest-old patients who died by 90 days after surgery, only 41% were as a result of their colon cancer. Factors associated with poorer 90-day and 1-year overall survival are presented in Table 3. At both time points, older age, male gender, frailty, increased hospitalizations in the prior year, and dementia were most strongly associated with poorer survival. In general, specific comorbidities were not associated with 90-day or 1-year survival. In addition, AJCC stage III disease and being widowed were highly associated with poorer survival at one year. Overall survival by AJCC stage was 90.0% for stage 1, 87.2% for stage 2, and 79.0% for stage 3. At both time points, frailty had the strongest association with poorer survival (90-day: odds ratio 10.4 [95% confidence interval 7.6-14.2], p<0.001; 1-year: odds ratio 8.4 [95% confidence interval 6.4-11.1], p<0.001). Overall survival for frail vs. not frail patients was 58.8% vs. 95.0%% at 90-days, and 41.5% vs. 87.7% at 1-year (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Overall survival for colon cancer patients ≥80 years of age who underwent elective colectomy.

Table 3.

Factors associated with 90-day and 1-year overall survival after elective colectomy in colon cancer patients ≥80 years of agea

| Predictors of 90-day Mortality | Predictors of 1-Year Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.6 (1.2-2.2) | 0.001 | 1.5 (1.3-1.9) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 0.8 (0.4-1.6) | 0.60 | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 0.44 |

| Other | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | 0.46 | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | 0.55 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Widowed | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 0.15 | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 0.004 |

| Single, Separated, Divorced | 1.1 (0.7-1.9) | 0.57 | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 0.26 |

| AJCC Stageb | ||||

| I | Reference | Reference | ||

| II | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 0.89 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 0.28 |

| III | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 0.75 | 2.3 (1.8-1.9) | <0.001 |

| Overall Health Status | ||||

| Health Care Utilization | ||||

| # of hospitalization in year prior to diagnosis | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 0.001 | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 0.002 |

| # of ER visits in year prior to diagnosisb | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 0.33 | 1.02 (1.0-1.0) | 0.03 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Dementia | 4.5 (2.4-8.5) | <0.001 | 5.8 (3.1-11.0) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 0.97 | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 0.34 |

| Valvular disease | 0.4 (0.5-1.1) | 0.10 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 0.11 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | 0.35 | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 0.01 |

| Paralysis | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) | 0.57 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) | 0.35 |

| Other neurologic disorder | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.01 | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 0.88 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 0.32 |

| Diabetics (uncomplicated) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 0.59 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 0.68 |

| Diabetes (complicated) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 0.47 | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) | 0.83 |

| Renal failure | 1.1 (0.7-1.9) | 0.58 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 0.91 |

| Weight loss | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) | 0.91 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 0.62 |

| Electrolyte abnormalities | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 0.02 | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 0.05 |

| Depression | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) | 0.08 | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | <0.001 |

| Disability | ||||

| Home Oxygen | 1.3 (0.7-2.3) | 0.43 | 1.6 (1.0-2.4) | 0.04 |

| Mobility assist device | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | ||

| Cane/Walker | 0.9 (0.5-1.3) | 0.47 | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 0.17 |

| Wheelchair | 1.2 (0,7-2.0) | 0.39 | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 0.03 |

| Frailty | 10.4 (7.6-14.2) | <0.001 | 8.4 (6.4-11.1) | <0.001 |

Additionally adjusted for SEER registry, urban/rural residence, census track income and proportion of non-high school graduates, and year of diagnosis

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, Emergency Room

Figure 2.

Overall survival for colon cancer patients ≥80 years of age undergoing elective colectomy by frailty status.

DISCUSSION

Most oldest-old colon cancer patients do well after elective surgery, with 85.7% alive at 1-year. However, a significant proportion (6.6%) of patients died by 90 days after surgery and the majority of these deaths were unrelated to their colon cancer diagnosis. The ability to identify those patients at increased risk of early post-operative mortality after elective surgery has a number of significant implications. This information would improve the informed consent process by better aligning patient expectations with anticipated outcomes, specifically the risk of early post-operative mortality. Our prior research has demonstrated that the majority of colon cancer patients ≥80 years of age (including those not selected for surgical resection of their cancer) die of causes unrelated to their colon cancer.28 Therefore, the ability to prospectively identify a cohort of patients being considered for elective surgery who are at risk for especially poor short-term survival may facilitate open conversations about the risk of death and the option of non-operative therapeutic alternatives for management of the colon cancer. Finally, pre-operative identification of at-risk patients could guide pre-operative referral to a geriatrician for optimization prior to surgery.

After controlling for patient demographics, cancer stage, and other health factors, patient frailty was the strongest predictor of poor short-term post-operative survival. Twenty-seven percent of the deaths during the first 90-days after surgery occurred in patients identified as frail. This raises the possibility that frailty could be used as a marker to identify patients at increased risk of early post-operative mortality.

Frailty has been measured in the clinical setting through a variety of means. Two commonly used approaches to assess frailty have been described. The first defines frailty based on a “classic phenotype” comprised by specific factors, including weight loss, weakness, poor endurance, slowness, and low activity.12 The second method depends less on which specific factors are present, but focuses instead on the absolute number of accumulated factors to determine if a patient is frail.13 These two approaches have been captured through a variety of scoring systems requiring either direct patient assessment (such as measurement of grip strength, time required to walk 15 feet, etc.),6,10,12 brief patient surveys,29,30 and evaluations based on more comprehensive geriatric assessments.31 Although each measure has been found to be predictive of frailty and outcomes, a major limitation to their utility is surgeons’ ability and willingness to adopt them into everyday clinical practice.

Surgeons perform a thorough assessment of patients overall well-being at the time of a pre-operative evaluation, relying on assessment of comorbidity through review of the medical records and conversations with primary care doctors. However, although surgeon awareness of the importance of frailty is increasing, the lack of an efficient means of assessing frailty in the clinical setting means that surgeons rely on their clinical judgment to provide an overall gestalt of their patients’ wellness and ability to undergo surgery, rather than a formal assessment of frailty. In our study, the most common frailty criteria included difficulty walking, weight loss and frequent falls. Because these frailty factors could exist in the absence of documented comorbidity or disability, this important clinical factor may be overlooked in the standard surgeon pre-operative assessment.

By using the Hopkins ACG case-mix definition of frailty, we were able to identify frail patients at increased risk of early mortality through billing claims. The ability to identify frail patients using administrative data makes it likely that we would be able to identify these same patients prospectively through an electronic medical record. We would theoretically be able to create “flags” in the electronic medical record to alert surgeons that a particular patient is frail, and at increased risk of early mortality. The ease of identifying patients through the electronic medical record would overcome many of the implementation challenges other assessments of frailty have had when being adopted into clinical practice, and would provide surgeons with an efficient means of identifying these especially high-risk patients.

Several limitations exist to our study. First, our ability to assess patients’ overall health was limited to what we could abstract from the Medicare claims data. Although we were able to abstract specific comorbidities, we found little relationship between the presence of specific comorbidities and overall survival, even for those comorbidities which would be hypothesized to be associated with poor outcomes (such as congestive heart failure or complicated diabetes). This may reflect the fact that although the presence of the comorbidity was captured in the billing record, there is no information available regarding the severity of that comorbidity. This is especially relevant for those patients ≥80 years of age, many of whom will have accumulated a significant list of comorbidities; however, the very fact that they have lived to become octo- and nonagenarians implies that the severity of those comorbidities (or at least their impact on longevity) is likely low. Additionally, we were unable to directly assess disability (a factor known to be related to post-operative outcomes32), relying instead on indirect measures such as claims for home oxygen and ambulatory assist devices. Next, using billing data, we classified 4.4% of our oldest-old adults as frail, a significantly lower rate than that reported by Fried et al using prospectively collected data for patients >85 years of age (13%).12 In order to be considered frail using the definition validated by the ACG case-mix system, an appropriate contributing diagnosis needs to be documented, most likely by the patients’ primary care doctor or geriatrician. It is likely that the conditions which lead to a patient being considered frail are only documented in those oldest-old adults where the condition is having a significant negative impact on their overall well-being; as a result, those patients considered to be frail in our study likely reflect only the most severely impaired individuals. We are, therefore, likely underestimating the number of frail adults, and cannot comment on the relationship between lesser degrees of frailty and outcome. Finally, we were unable to assess the relationship between our measure of frailty and relevant outcomes other than survival (such as quality of life and maintaining functional independence).33

However, our study has a number of strengths. This is the first study to demonstrate that frailty, which is so strongly linked to early mortality, can be identified through billing codes. Although this measure likely underestimates the number of frail adults, those patients identified as being frail had remarkably poor short term survival. This measure of frailty has predictive value in identifying those patients at greatest risk of early mortality and would contribute critical clinical information to pre-operative discussions. This has the potential to significantly improve the decision-making process for surgeons and their oldest-old patients.

CONCLUSION

In this analysis of the SEER-Medicare database, we identified frailty as the strongest predictor of a poor short-term survival after elective colon cancer surgery in patients ≥80 years of age. The ability to identify frailty with administrative data suggests that it should be possible to create “frailty flags” in the electronic medical record, thereby identifying individuals who are at highest risk for poor post-operative survival. The measure of frailty that we used is highly predictive and could be incorporated into surgical clinical practice via the electronic medical record. Given the demonstrated resistance of physicians to the incorporation of decision-support tools in clinical practice,34-36 the potential for seamless integration of high-value indicators of risk through the electronic medical record has important implications for streamlining surgeon practice and supporting decision-making, and is a promising direction for future research.

SYNOPSIS.

Most colon cancer patients ≥80 years of age do well after elective colectomy, with 90-day and 1-year overall survival of 93.4% and 85.7%, respectively. Frailty was identified as the strongest predictor of poor short-term post-operative survival.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. The collection of the California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Financial disclosure: Support for this project was provided by the Health Innovation Program and the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR), grant 1UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health and by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, grant P30CA014520-34 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Additional funding for this project was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from The Wisconsin Partnership Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Werner CA. [March 22, 2012];The Older Population: 2010. 2010 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-09.pdf.

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. [June 5, 2011];SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. 2011 http://seer.cancer.gov/cxr/1975_2008/.

- 3.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr., Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Dec 30;341(27):2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope AM, Tarlov AR. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Stiegmann GV, Moss M. Frailty predicts increased hospital and six-month healthcare cost following colorectal surgery in older adults. American journal of surgery. 2011 Nov;202(5):511–514. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010 Jun;210(6):901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P, Borrie MJ, Speechley M. Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2009 Jan-Feb;48(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxton A, Velanovich V. Preoperative frailty and quality of life as predictors of postoperative complications. Annals of surgery. 2011 Jun;253(6):1223–1229. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318214bce7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhoy MS, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: a prospective observational cohort study. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2010 Dec;76(3):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson TN, Wallace JI, Wu DS, et al. Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011 Jul;213(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.056. discussion 42-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, et al. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Annals of surgery. 2009 Sep;250(3):449–455. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b45598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007 Jul;62(7):722–727. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunitake H, Zingmond DS, Ryoo J, Ko CY. Caring for octogenarian and nonagenarian patients with colorectal cancer: what should our standards and expectations be? Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2010 May;53(5):735–743. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181cdd658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark AJ, Stockton D, Elder A, Wilson RG, Dunlop MG. Assessment of outcomes after colorectal cancer resection in the elderly as a rationale for screening and early detection. The British journal of surgery. 2004 Oct;91(10):1345–1351. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hessman O, Bergkvist L, Strom S. Colorectal cancer in patients over 75 years of age--determinants of outcome. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 1997 Feb;23(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)80136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heriot AG, Tekkis PP, Smith JJ, et al. Prediction of postoperative mortality in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2006 Jun;49(6):816–824. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenblatt DY, Weber SM, O'Connor ES, LoConte NK, Liou JI, Smith MA. Readmission after colectomy for cancer predicts one-year mortality. Ann Surg. 2010 Apr;251(4):659–669. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d27c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connor ES, Greenblatt DY, LoConte NK, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer with poor prognostic features. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Sep 1;29(25):3381–3388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES, et al. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results--Medicare data. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Nov 20;29(33):4401–4409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993 Aug;31(8):732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002 Aug;40(8 Suppl):IV, 3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Dahman B, Fitzgerald TL. Adjuvant chemotherapy after resection in elderly Medicare and Medicaid patients with colon cancer. Archives of internal medicine. 2008 Mar 10;168(5):521–529. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobie SA, Baldwin LM, Dominitz JA, Matthews B, Billingsley K, Barlow W. Completion of therapy by Medicare patients with stage III colon cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006 May 3;98(9):610–619. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med. Care. 1998 Jan;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor DH, Jr., Ostbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):807–815. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieberman R, Abrams C, Weiner JP. Development and Evaluation of the Johns Hopkins University Risk Adjustment Models for Medicare+Choice Plan Payment. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Baltimore, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuman H, O'Connor ES, Weiss J, LoConte NK, Greenblatt DY, Smith MA. Surgical Treatment of Colon Cancer in Patients Older than 80 Years of Age. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Jun 3-7;29(15S):6071. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age and ageing. 2006 Sep;35(5):526–529. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steverink N, Slaets JPJ, Schuurmans H, Lis van M. Measuring frailty. development and testing of the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI). Gerontologist. 2001;41:263–237. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mitnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elderly people. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007 Jul;62(7):738–743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimick JB, Osborne NH, Hall BL, Ko CY, Birkmeyer JD. Risk adjustment for comparing hospital quality with surgery: how many variables are needed? Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010 Apr;210(4):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reuben DB. Medical care for the final years of life: “When you're 83, it's not going to be 20 years”. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009 Dec 23;302(24):2686–2694. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donnell S, Cranney A, Jacobsen MJ, Graham ID, O'Connor AM, Tugwell P. Understanding and overcoming the barriers of implementing patient decision aids in clinical practice. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2006 Apr;12(2):174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caldon LJ, Collins KA, Reed MW, et al. Clinicians’ concerns about decision support interventions for patients facing breast cancer surgery options: understanding the challenge of implementing shared decision-making. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. 2011 Jun;14(2):133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conley DM, Singer SJ, Edmondson L, Berry WR, Gawande AA. Effective surgical safety checklist implementation. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011 May;212(5):873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]