Abstract

Although correlated changes between personality and alcohol involvement have been shown, the functional relation between these constructs is also of theoretical and clinical interest. Using bivariate latent difference score models, we examined transactional relations (i.e., personality predicting changes in alcohol involvement, which in turn predicts changes in personality) across two distinct but overlapping developmental time frames (i.e., across college and during young adulthood) using two large, prospective samples. Across college, there was some evidence that alcohol involvement predicted changes in personality; however, these findings were limited to models that included more proximal measures of alcohol use. When examined across a longer timeframe, we found no evidence that alcohol involvement significantly predicted changes in personality but found some evidence that personality predicted changes in alcohol use. We did find reliable evidence of correlated changes between personality and alcohol use, especially during emerging adulthood. The findings from our datasets highlight that the impact of alcohol involvement on personality change may be limited to shorter intervals during specific developmental timeframes and that the relation between changes in personality and alcohol involvement may be best viewed from a noncausal perspective.

Keywords: personality change, alcohol use, developmental models

The relation between personality and alcohol involvement (including heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders) has long been of interest to researchers (see Sher, Trull, Bartholow, & Vieth, 1999) and more recently changes in personality have been linked to changes in alcohol involvement (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2009, 2010). These findings highlight co-occurring changes between specific personality traits and alcohol-related problems (see Littlefield & Sher, 2010, in press, for a more detailed discussion).

However, more recently researchers have shown interest in delineating the functional relation between changes in alcohol involvement and personality change (see the Discussion section about the limitations of structural equation models to delineate among various causal assumptions). Using a person-centered approach, Littlefield, Sher, and Steinley (2010) modeled developmental trajectory groups of impulsivity from ages 18–35 and tested for differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems across these groups. Although these data were correlational in nature and thus causal relations between impulsivity and alcohol cannot be adequately resolved, patterns of covariation between these constructs suggest that alcohol use is a trailing indicator (i.e., occurs as a result of) of impulsivity development (as opposed to a leading, etiologic predictor of developmental course; see Sher et al., 2004; Littlefield, Sher, & Steinley, 2010, for more details). Also using a person-centered approach to model trajectories of impulsivity during adolescence, White et al. (2011) found impulsivity trajectory groups differed on a range of alcohol outcomes (e.g., alcohol dependence), such that the less impulsive groups were lower on these measures of alcohol involvement than the more impulsive groups. In one of the trajectory groups, there was also evidence that previous drinking significantly predicted subsequent impulsive behavior during adolescence. The pattern of findings suggested that chronic heavy drinking was related to subsequent elevations in impulsivity but that time-limited drinking resulted in short-term elevations (i.e., 1 year) in impulsivity that later returned to normative levels of impulsivity.

Using a variable-centered approach in a prospective sample, Chassin et al. (2010) found that, from ages 15 to 21 years, higher alcohol use significantly predicted a significant decline in psychosocial maturity (a construct similar to the personality trait conscientiousness) 6 months later (although the effect size was small, β = −.03), whereas psychosocial maturity did not significantly predict analogous changes in alcohol use. Using latent difference score (LDS) models (McArdle, 2009), Quinn, Stappenbeck, and Fromme (2011) concluded that heavy drinking during the sophomore year of college prospectively predicted change in sensation seeking and impulsivity between high school and senior year of college. Based on these findings, Quinn et al. concluded their models provide evidence for a directional transactional relation (i.e., personality influences drinking, and drinking in turn influences change in personality) between heavy alcohol use and subsequent personality, and that transactional relations may underlie prior findings demonstrating correlated changes among these constructs.

In sum, clear evidence exists that changes in personality and alcohol involvement are linked across different developmental timeframes; however, the functional relation between personality and alcohol involvement is less clear. Some evidence suggests that changes in alcohol involvement follow changes in personality (i.e., Littlefield, Sher, & Steinley, 2010), that personality change is influenced by alcohol involvement (Chassin et al., 2010; White et al., 2011), and that personality and alcohol involvement have directional transactional relations (Quinn et al., 2011).

Clearly, better understanding of the processes that influence personality change is of interest to the field (see Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). Theoretically, empirical evidence that sheds light on the nature of the relations between changes in personality and alcohol involvement would allow us to further refine various models of the personality–alcohol relation. For example, if more robust support is found for correlated changes between personality and alcohol involvement rather than directional relations, then models that highlight the importance of potential third-variable explanations (e.g., genetic predispositions) of these relations should be further considered (see Littlefield & Sher, 2010). Clinically, delineating the functional relation between changes and personality and alcohol involvement could guide intervention and treatment approaches. For example, if personality is shown to predict changes in alcohol involvement, then personality-targeted interventions would have further support. On the other hand, if alcohol involvement is shown to be a reliable predictor of personality change, then targeting drinking may help prevent detrimental changes in personality, which in turn could reduce a range of negative outcomes (e.g., Mroczek & Spiro, 2007).

Thus, the current article has two primary goals: (a) to test transactional relations and correlated changes in a longitudinal study of college students (i.e., the Intensive Multivariate Prospective Alcohol College-Transitions Study [IMPACTS]; N = 3,720 at Wave 1) during two distinct timeframes (i.e., approximately ages 18–21 and 18–25), and (b) to test for evidence of directional transactional relations for the data used to demonstrate correlated change in Littlefield et al. (2010, 2011; i.e., the Alcohol, Health, and Behavior [AHB] Study; N = 489 at Wave 1).

Method

Participants and Procedure

IMPACTS

Participants (i.e., those individuals who completed a precollege survey in the summer prior to matriculation) were 3,720 (88.0% of the original precollege sampling frame) college students from IMPACTS (for a detailed description of the sample, see Sher & Rutledge, 2007). IMPACTS is a longitudinal study starting in the fall semester of 2002, in which first-time college students who were enrolled at a large Midwestern university were recruited for participation and completed an online survey every semester until their fourth year (see Sher & Rutledge, 2007).

For the three assessment periods during the college years under consideration, 2,8021 participants (77% of individuals who completed a precollege survey) completed assessments relevant to the current study at fall freshman year, 2,424 (87% of participants from freshman year) at spring sophomore year, and 2,429 (87% of participants from freshman year) at fall senior year. For a subset of analyses, we also used a postcollege assessment (n = 1,248; Mage = 24.68 years, SD = 0.51).

AHB study

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study on family history of alcoholism (FHA) and other correlates of alcoholism (see Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991, for a full description of the study). The baseline sample comprised of 489 first-year college students (46% men, Mage = 18.2 years) from a large Midwestern university. Half (51%) of the respondents were classified as FHA positive (FHA+) and were prospectively assessed seven times over 17 years (roughly at ages 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, and 35) by both interview and paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Overall retention was good; over 84% of participants were retained over the first 11 years of the study, and over 78% were retained through Year 17 (Mage = 34.5 years).

Measures

Heavy drinking

We used three self-report measures of alcohol use as indicators of a latent heavy drinking variable in both the AHB Study and IMPACTS. For the AHB Study, frequency of alcohol in the past week, frequency of intoxication during the past month, and heavy drinking frequency (i.e., five or more drinks at a single setting) during the past month were used as indicators. For IMPACTS, self-reported quantity of alcohol in the past 3 months, frequency of intoxication during the past month, and heavy drinking frequency during the past month were used as indicators.

Problematic alcohol involvement

A sum of 27 items consisting of both negative consequences associated with drinking and symptoms related to alcohol dependence (see Littlefield et al., 2009, 2010; Sher et al., 1991) was calculated at each wave. Participants were asked if, in the past year, they had experienced alcohol-related consequences or symptoms (e.g., In the past year, have you … “Gotten in trouble at work or school because of drinking?”). Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha, ranged from .87–.90.

Personality

In the AHB Study, a sum of 10 items was used to assess impulsivity at baseline (age 18) and subsequently at ages 25, 29, and 35, respectively. Six of these items (e.g., I often follow my instincts, hunches, or intuition without thinking through all the details) were drawn from the Novelty Seeking dimension from the short-form of the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (Short-TPQ; Sher, Wood, Crews, & Vandiver, 1995) and the remaining four items (e.g., I often do things on the spur of the moment) were taken from the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1968). For IMPACTS, the Novelty Seeking dimension from the Short-TPQ (Sher et al., 1995) was used. Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha, ranged from .75–.81 for the impulsivity scale and from .71–.72 for novelty seeking.

Analytic Procedure

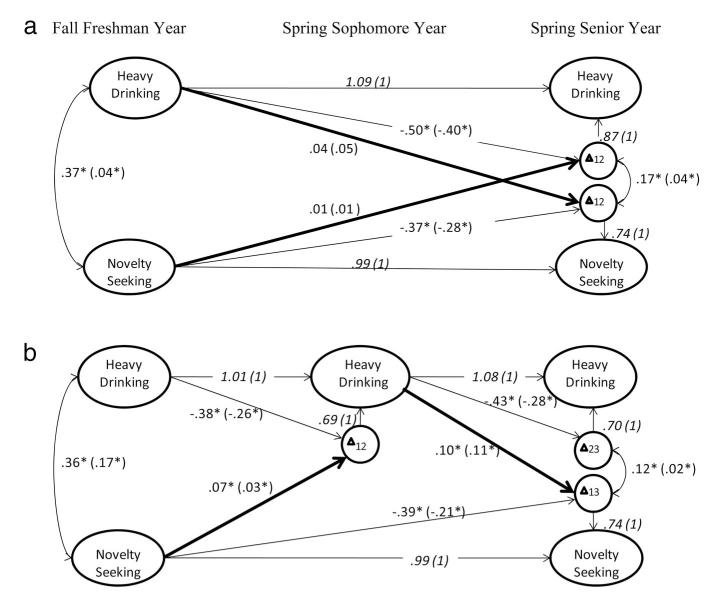

First, we estimated bivariate LDS models between novelty seeking and heavy drinking in IMPACTS. At each wave, a latent variable for novelty seeking was created from three parcels of the Novelty Seeking dimension. A latent variable for heavy drinking at each wave was created from quantity of drinking, frequency of binge drinking, and frequency of perceived intoxication. For the analyses shown in Figure 1, factor loadings were constrained to equality within construct across waves (although models without these and more restrictive constraints yielded nearly identical results to those presented here). We estimated three models in these data. In first model (Model 1), we used parallel assessments of personality and heavy drinking (i.e., approximately at age 18 and 21 years) at fall freshman and spring senior year. In the second model (Model 2), given the findings in the extant literature that more proximal alcohol use appears to predict subsequent changes in personality (i.e., Chassin et al., 2010; Quinn et al., 2011; White et al., 2011), we estimated the influence of spring sophomore year drinking on changes in personality between 18 and 21 years. In the third model (Model 3), we examined the transactional relation between personality and heavy drinking in a subset of the original participants (n = 1,248) using three assessments of personality and heavy drinking, respectively (roughly at ages 18, 21, and 25 years). To allow for missing data, all models were estimated in Mplus, version 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2010) using full information maximum likelihood.

Figure 1.

Latent difference score models from IMPACTS data using parallel assessments (a) and more proximal heavy drinking (b). Values are standardized regression coefficients and correlations (unstandardized estimates shown in parentheses). Bolded lines indicate transactional paths. Italicized lines reflect constraints imposed on the model.  = latent difference score. * p < .05.

= latent difference score. * p < .05.

Results

IMPACTS Data

Figure 1 shows the findings for Models 1 (see Figure1a) and 2 (see Figure1b). In Model 1, the pathways from novelty seeking to changes in heavy drinking and heavy drinking to changes in novelty seeking were small in magnitude and statistically nonsignificant, although changes in heavy drinking and alcohol problems correlated significantly across this timeframe. However, in Model 2, fall freshman year novelty seeking significantly predicted changes in alcohol-related problems between fall freshman and spring sophomore year; in turn, heavy drinking at spring sophomore year significantly predicted changes in novelty seeking between fall freshman and spring senior year. Again, changes in heavy drinking and novelty seeking correlated significantly in this model.

Figure 2 shows the findings for Model 3. There were no statistically significant transactional pathways during the college years (consistent with Model 1); however, novelty seeking at age 21 predicted changes in heavy drinking between ages 21 and 25. There was no evidence that heavy drinking significantly predicted change in novelty seeking, but again there was evidence of significantly correlated changes between these constructs.

Figure 2.

Latent difference score models from IMPACTS data from ages 18–25. Values are standardized regression coefficients and correlations (unstandardized estimates shown in parentheses). Bolded lines indicate transactional pathways. Italicized lines reflect constraints imposed on the model.  = latent difference score. * p <.05.

= latent difference score. * p <.05.

AHB Study Latent Difference Score Models

To test for evidence of a transactional relation between impulsivity-related traits and alcohol involvement, we used the four waves of AHB Study data (roughly at ages 18, 25, 29, and 35 years) that were previously used in Littlefield et al. (2009, 2010). We conducted two LDS models, the first involving impulsivity and heavy drinking and the second linking impulsivity and alcohol-related problems. In the first model, there was no evidence of significant transactional pathways (i.e., impulsivity did not significantly predict changes in heavy drinking and heavy drinking did not significantly predict changes in impulsivity; β range: −.04 to.09, p range: .17–.66), though changes in heavy drinking correlated significantly with changes in impulsivity between ages 18 and 25 (r = .19, p = .001). In the second model involving alcohol-related problems, there was only one significant directional pathway, but this path was small in magnitude and was in the opposite direction of hypothesized transactional relations: impulsivity at age 18 was negatively related to changes in alcoholrelated problems between ages 18 and 25 (β = −.11, p = .04). No other pathways were statistically significant (β range: −.09 to .11, p range: .12–.36). Changes in alcohol-related problems correlated significantly with changes in impulsivity between ages 18 and 25 (r = .17, p = .02) and approached significance between ages 25 and 29 (r = .18, p = .06). Therefore, we did not find evidence that the correlated changes reported in Littlefield et al. (2009, 2010) (using bivariate latent growth modeling) appear to result from a directional transactional relation using LDS, though we did find evidence for correlated change between impulsivity and alcohol involvement.

Discussion

Using two large, prospective samples, we found evidence that directional transactional pathways differed across assessment frame and as a function of proximity of previous alcohol use. Using IMPACTS data and examining relations during the college years (roughly ages 18–21 years), we found no evidence for significant transactional pathways when parallel assessments were used; however, when a more proximal measure of heavy drinking was incorporated into the model, significant transactional pathways emerged. These findings are consistent with the extant literature that suggests proximal, but not necessarily distal, alcohol use influences subsequent changes in personality (Chassin et al., 2010; Quinn et al., 2011, Footnote 2; White et al., 2011). When using parallel assessments across a longer timeframe using a subsample of participants from these data, we found no evidence that heavy drinking significantly predicted change in personality, although personality at age 21 appeared to predict changes in heavy drinking from ages 21–25. These findings suggested that individuals who were higher in novelty seeking at age 18 were more likely to make increases in heavy drinking between ages 21 and 25. Across all models and between all timeframes, we found evidence of significant, correlated changes between personality and heavy drinking.

When using data from the AHB Study sample to examine changes across emerging and young adulthood, we found no evidence that heavy drinking or alcohol-related problems predicted subsequent changes in personality. In fact, the only path that was statistically significant suggested that impulsivity at age 18 was negatively related to changes in alcohol-related problems between ages 18 and 25. As with the IMPACTS data, we found evidence for correlated changes in alcohol involvement and personality, especially during emerging adulthood. Taken together, the findings from IMPACTS and the AHB Study highlight that the impact of alcohol involvement on personality change may be limited to shorter intervals during specific developmental timeframes and that the relation between changes in personality and alcohol involvement may be best viewed from a noncausal perspective.

Notably, the findings of correlated change during emerging adulthood appear robust across different statistical methodologies, because we were able to demonstrate correlated changes using LDS models, bivariate growth score models (Littlefield et al., 2009, 2010), and person-centered approaches (Littlefield, Sher, & Steinley, 2010). Given these findings, we conclude that little evidence exists for directional transactional pathways between alcohol involvement and personality in our data, though there appears to be methodologically robust evidence for correlated change, especially during emerging adulthood. These findings highlight the theoretical implication that changes in personality and alcohol involvement should be viewed from a developmental context, which assumes correlated changes rather than unidirectional causality in the data (see Scollon & Diener, 2006, for a similar discussion involving correlated changes in personality with other outcomes). Further, third-variable explanations, such as underlying genetic influences on personality, alcohol involvement, and potential mediators (see Littlefield et al., 2011), could be a focus for future research delineating the developmental relations between personality and alcohol involvement. As noted elsewhere (e.g., Littlefield et al., 2009), from the standpoint of assessment, changes in both problematic drinking behaviors and personality may indicate that the individual has undergone substantial and beneficial change that is likely to be durable, whereas changes in drinking behaviors but not personality may signal increased risk for relapse or continued risk for associated problem behaviors.

On a more technical note, adjudication is not possible between the autoregressive latent change models considered here and the growth curve models considered by Littlefield et al. (2009, 2010), which are nonstationary moving-average models. As Rovine and Molenaar (2005) demonstrated, any nonstationary moving-average model can be reexpressed as an equally well-fitting autoregressive model and vice versa. Tomarken and Waller (2003) provided a detailed discussion and demonstration of the issue of equivalent model fits with different causal assumptions in structural equation modeling. Tomarken and Waller recommended that researchers acknowledge the presence of plausible equivalent models in study designs that cannot distinguish causal and noncausal models (such as data presented here and other correlational studies) and design studies to rule out such alternatives. Future research that seeks to clarify the preferable alternative would require controlled experiments and a universally agreed-on instrumental variable. Further, although we lacked sufficient repeated measures of personality in our IMPACTS data that focused on the college years, modeling approaches not considered here could more appropriately model nonparallel assessments between personality and heavy drinking (see McArdle & Hamagami, 2004).

More generally, we believe that excessive alcohol consumption, especially levels associated with severe dependence, could alter personality in key ways. Indeed, Barnes’s (1979) distinction between “prealcoholic” and “clinical alcoholic” personalities was based in large part on the high levels of negative affectivity seen in clinical alcoholic samples in contrast to the personality profiles of those who later develop alcoholism. Moreover, these “clinical alcoholic” traits related to negative affectivity appear to normalize over time in abstinent alcoholics after treatment (e.g., Sutherland, 1997). Such changes in personality are consistent with models of neuroadaptation to high levels of alcohol consumption (i.e., allostasis; Koob & Le Moal, 2001). In addition to the neuroadaptational effects associated with heavy alcohol consumption, if heavy alcohol involvement preempts engagement in normative developmental challenges that goad personality change, we also might expect to see the effects of drinking on various measures of psychosocial maturity (Baumrind & Moselle, 1985). However, what is less clear are the levels of chronic consumption required to induce neuroadaptive changes or interfere with normative role development and how common this particular type of chronic consumption is in college samples such as those used here. Regardless, taken together with the existing research literature, the findings reported here suggest that it should not be axiomatic that personality causally relates to alcohol involvement (the theoretical assumption in Littlefield et al., 2010) and that the alternative causal and noncausal relations should be entertained.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant F31AA019596, Grant T32AA13526, Grant R01AA13987, Grant R37AA07231, Grant KO5AA017242, and Grant P60 AA11998). We gratefully acknowledge Patrick D. Quinn, Cynthia A. Stappenbeck, and Kim Fromme for providing details on their analyses, including outputs from their models and the staff of the Alcohol, Health, and Behavior Study and the Intensive Multivariate Prospective Alcohol College-Transitions Study for their data collection and management.

Footnotes

As noted in Sher and Rutledge (2007), a supplement to fall freshman year was conducted at the time of spring freshman year. In this supplement, selected fall freshman year measures were obtained from 239 individuals who did not participate at fall freshman year, including personality assessments.

References

- Barnes GE. The alcoholic personality: A reanalysis of the literature. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1979;40:571–634. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1979.40.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D, Moselle KA. A developmental perspective on adolescent drug abuse. Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse. 1985;4:41–67. doi: 10.1300/J251v04n03_03. doi:10.1300/J251v04n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Dmitrieva J, Modecki K, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Piquero AR, Losoya SH. Does adolescent alcohol and marijuana use predict suppressed growth in psychosocial maturity among male juvenile offenders? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:48–60. doi: 10.1037/a0017692. doi:10.1037/a0017692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Educational and Industrial Testing Services; San Diego, CA: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Agrawal A, Ellingson JM, Kristjansson S, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Sher KJ. Does variance in drinking motives explain the genetic overlap between personality and alcohol use disorder symptoms? A twin study of young women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:2242–2250. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ. The multiple, distinct ways that personality contributes to alcohol use disorders. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010;4:767–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00296.x. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ. Personality and substance use disorders. In K. J. Sher (Ed.), Oxford handbook of substance use disorders. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Steinley D. Developmental trajectories of impulsivity and their association with alcohol use and related outcomes during emerging and young adulthood I. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1409–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. doi:10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and the “maturing out” of alcohol problems? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. doi:10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Methods for dynamic changes hypotheses. In: Montfort KV, Oud J, Satorra A, editors. Recent developments on structural equation models: Theory and applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2004. pp. 295–335. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczej DK, Spiro A. Personality change influences mortality in older men. Psychological Science. 2007;18:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Stappenbeck CA, Fromme K. Collegiate heavy drinking prospectively predicts change in sensation seeking and impulsivity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:543–556. doi: 10.1037/a0023159. doi:10.1037/ a0023159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Bogg T. A 30-year longitudinal study of the relationships between conscientiousness-related traits, and the family structure and health-behavior factors that affect health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:325–354. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovine M, Molenaar PCM. Relating factor models for longitudinal data to quasi-simplex and NARMA models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:83–114. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4001_4. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr4001_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Diener E. Love, work, and changes in extraversion and neuroticism over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:1152–1165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Watson A. Trajectories of dynamic predictors of disorder: Their meanings and implications. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:825–856. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC, Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow B, Vieth A. Personality and alcoholism: Issues, methods, and etiological processes. In: Blane H, Leonard K, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 54–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood P, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood M, Crews T, Vandiver, T A. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire. Reliability and validity studies and derivation of a short form. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:195–208. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.2.195. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland I. The development and application of a questionnaire to assess the changing personalities of substance addicts during the first year of recovery. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1997;53:253–262. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199704)53:3<253::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-s. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199704)53:3<253::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Potential problems with “well fitting” models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:578–598. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Marmorstein NR, Crews FT, Bates ME, Mun E, Loeber R. Associations between heavy drinking and changes in impulse behavior among adolescent boys. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01345.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]