Abstract

Human social motivation is characterized by the pursuit of social reward and the avoidance of social punishment. The ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens (VS/Nacc), in particular, has been implicated in the reward component of social motivation, i.e., the ‘wanting’ of social incentives like approval. However, it is unclear to what extent the VS/Nacc is involved in avoiding social punishment like disapproval, an intrinsically pleasant outcome. Thus, we conducted an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study using a social incentive delay task with dynamic video stimuli instead of static pictures as social incentives in order to examine participants' motivation for social reward gain and social punishment avoidance. As predicted, the anticipation of avoidable social punishment (i.e., disapproval) recruited the VS/Nacc in a manner that was similar to VS/Nacc activation observed during the anticipation of social reward gain (i.e., approval). Stronger VS/Nacc activity was accompanied by faster reaction times of the participants to obtain those desired outcomes. This data support the assumption that dynamic social incentives elicit robust VS/Nacc activity, which likely reflects motivation to obtain social reward and to avoid social punishment. Clinical implications regarding the involvement of the VS/Nacc in social motivation dysfunction in autism and social phobia are discussed.

Keywords: ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, social reward, social punishment, motivation, avoidance

1. Introduction

Understanding the brain's receptivity to social reward and social punishment has generated extensive interest recently (Falk, Way, & Jasinska, 2012; Frith & Frith, 2012; Richards, Plate, & Ernst, 2011; Rilling & Sanfey, 2011; Seymour, Singer, & Dolan, 2007, Vrtička & Vuilleumier, 2012). However, there is still a relative paucity of neurobiological research on the human motivation for obtaining social reward and avoiding social punishment. A better knowledge of the brain-behavioral mechanisms associated with the motivation for social engagement is not only imperative for understanding the biology of socially motivated behaviors, but also for comprehending the neuropsychopathology of complex disorders such as autism, social phobia and depression which are often characterized by impairments alluded to aberrant social motivation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Social motivation can be described as an individual's propensity to obtain social rewards (Chevallier, Kohls, Troiani, Brodkin, & Schultz, 2012) (e.g., approval by others), and to avoid social punishment (e.g., disapproval by others) (Buss, 1983). Research has shown that the processing of incentives like rewards and punishments can be subdivided in at least two successive phases, with anticipation of the desired outcome and the appraisal of the experienced outcome each having a unique but interrelated neural basis (Reynolds & Berridge, 2002). Specifically, the possibility of obtaining positive incentives (e.g., praise) will trigger approach behavior, while negative incentives (e.g., threat of reprimand) facilitate avoidance (reviewed in (Young, 1959)).

One prominent experimental paradigm, the monetary incentive delay task (MID), was introduced by Knutson and colleagues (Knutson, Westdorp, Kaiser, & Hommer, 2000) to investigate the neural processing of reward and punishment with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The MID separately assesses anticipatory versus consummatory responses to monetary incentives (i.e., monetary gain or loss), but has most recently been modified to study the processing of social stimuli as well (Kohls et al., 2011; Kohls, Schulte-Rüther, et al., 2012; Rademacher et al., 2010; Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009). Using the incentive delay paradigm, Spreckelmeyer and colleagues were the first to compare blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signals for anticipation of social (i.e., affirmative faces) versus monetary reward in healthy participants (Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009). In line with Knutson's studies (Knutson, Adams, Fong, & Hommer, 2001; Knutson, Fong, Adams, Varner, & Hommer, 2001; Knutson, Taylor, Kaufman, Peterson, & Glover, 2005) and animal work (Robinson, Zitzman, & Williams, 2011), cue-triggered anticipation of social and monetary gain activated the dopaminergic mesocorticolimbic reward circuitry, including ventral striatum (VS)/nucleus accumbens (Nacc), with greater VS/Nacc activity for more salient incentives (e.g., exuberant vs. mild smiles; €3 vs. €1). These findings were replicated in more recent studies (Dichter, Richey, Rittenberg, Sabatino, & Bodfish, 2012; Gasic et al., 2009; Kohls, Schulte-Rüther, et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2010), suggesting that the VS/Nacc functions as a general, modality-independent mediator of reward seeking, including the motivation for obtaining social reward (Kohls, Chevallier, Troiani, & Schultz, 2012).

Threat of punishment, a well-known motivator of human social behavior (Balliet, Mulder, & Van Lange, 2011; Rilling & Sanfey, 2011; Seymour et al., 2007), by contrast, has not been nearly as well studied with functional neuroimaging. Thus, less is known about the neural mechanisms underlying the motivation to avoid social punishments (e.g., disapproval). Recently, however, several fMRI studies have shown that cue-induced avoidance of negative, non-social situations such as monetary loss (Carter, MacInnes, Huettel, & Adcock, 2009; Delgado, Jou, LeDoux, & Phelps, 2009; Guitart-Masip et al., 2011; Kim, Shimojo, & O'Doherty, 2006; Stark et al., 2011; Tom, Fox, Trepel, & Poldrack, 2007), electric shocks (Jensen et al., 2003; Mobbs et al., 2009; Seymour et al., 2005) or aversive pictures (Levita, Hoskin, & Champi, 2012) activate the VS/Nacc region in a consistent fashion. Together, these findings suggest the involvement of the VS/Nacc in both appetitive (i.e., reward approach-related) and aversive (i.e., punishment avoidance-related) motivated behavior (Bromberg-Martin, Matsumoto, & Hikosaka, 2010; Carlezon Jr. & Thomas, 2009; Horvitz, 2000; Ikemoto & Panksepp, 1999; Salamone, 1994). This conclusion is further supported by animal data showing that firing of dopaminergic Nacc neurons contributes to reward-seeking as well as anticipatory avoidance in response to potentially punishing events (e.g.,( Matsumoto & Hikosaka, 2009; Pennartz, Groenewegen, & Lopes da Silva, 1994; Reynolds & Berridge, 2002, 2008; Schoenbaum & Setlow, 2003)). Thus, while cue-induced VS/Nacc activation has been frequently associated with the anticipation of positive stimuli like rewards (Berridge, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2009; Berridge & Robinson, 2003; Kohls, Chevallier, et al., 2012), the bivalent activation pattern that has been observed suggests that the VS/Nacc is involved in encoding the motivational value of aversive and to-be-avoided stimuli as well (Reynolds & Berridge, 2002). Presumably this should also pertain to negative social stimuli such as social disapproval – or other forms of social punishment – that humans generally strive to avoid (Homans, 1958), but to date this has not been studied.

A major challenge faced by current neuroscience research on social motivation in humans is the development of fMRI-appropriate experimental paradigms that employ ecologically valid stimuli that will initiate and maintain social approach and avoidance processes (Kohls, Chevallier, et al., 2012). One limitation of prior studies, for instance, has been the reliance on static face images to serve as social rewards (Risko, Laidlaw, Freeth, Foulsham, & Kingstone, 2012), which are, at best, only weakly rewarding (Kohls, Chevallier, et al., 2012). By contrast, dynamic stimuli, such as video clips of positive and negative face expressions, are perceived as more natural and engaging (Blatter & Schultz, 2006; Sato & Yoshikawa, 2007), and may contribute to more robust neural activation in social brain circuitry (Fox, Iaria, & Barton, 2009; J. Schultz & Pilz, 2009). Moreover, non-verbal signals like body postures and gestures are important social reinforcers (Skinner, 1953), but have not been addressed in previous imaging work on social motivation. To this end, we developed a novel set of video clips of actors providing non-verbal approval as social reward and nonverbal disapproval as social punishment, presented contingent on task performance in an incentive delay task ((Knutson et al., 2000; Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009); see below for details).

Taken together, the aim of the current investigation was twofold: First, to assess whether the neural mechanisms underlying the motivation for social reward gain (i.e., approval) would also apply to avoidance of social punishment (i.e., disapproval), with a special focus on the VS/Nacc; and second, to improve upon earlier studies by using dynamic video stimuli instead of static pictures as social incentives. We hypothesized that both the anticipation of social approval and avoidable social disapproval would activate the VS/Nacc in healthy adults.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Subjects

Study participants were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania graduate and undergraduate student community through flyers and word-of-mouth advertising. The initial sample consisted of thirty right-handed healthy volunteers with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Data from five participants were incomplete and could not be used for data analyses (e.g., missing logfiles). Subsequently, three participants were excluded because of excessive head movements during the fMRI scan (i.e., more than 1.5 mm of translational motion in the x, y, and z direction throughout the course of a run). Thus, the final sample comprised twenty-two volunteers (11 females; age: 25.6 ± 3.5 years; range: 22 - 35 years; race/ethnicity: 16 Caucasian, 3 African American, 2 Asian, 1 Hispanic). All denied a history of psychiatric and neurological problems. None reported taking medications affecting the central nervous system at time of testing or within the last two months. All participants gave written informed consent to be part of this study, which was approved by the local IRB. Volunteers were compensated for their participation.

2.2. Incentive delay task

The social incentive delay task (SID) is an adaptation of Knutson's monetary incentive delay task (Knutson et al., 2005, 2000), and aims to examine participants' motivation to receive social rewards (Rademacher et al., 2010; Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009). To increase the ecological validity of the paradigm, we replaced static photos with short movie clips of actors expressing facial expressions along with other nonverbal gestures (Fig. 1; see below for details).

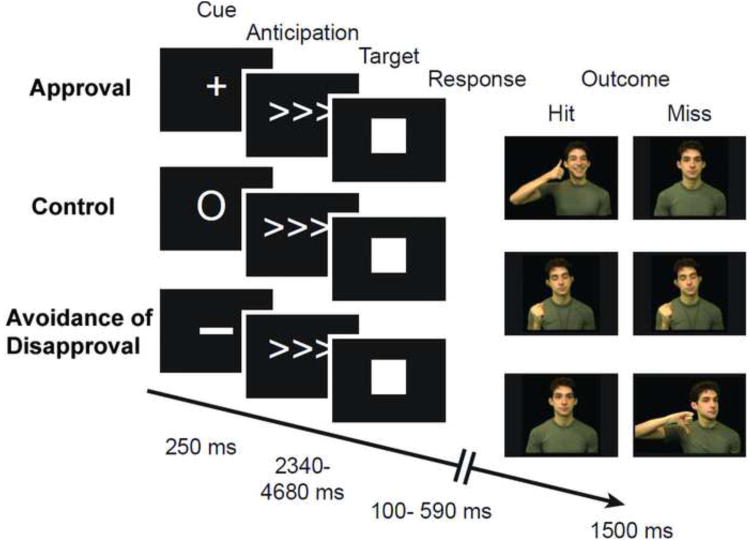

Fig.1.

Illustration of the social incentive delay task including two different task versions: (1) seeking social approval (APR), and (2) avoiding social disapproval (AVOI). Each task comprised a total of 48 incentive trials and 48 control trials (in addition to null events) presented across six runs in total, three for each task type, with intermixed incentive and control trials in each run. To increase the ecological validity of the paradigm, static photos were replaced with short movie clips of actors expressing facial expressions along with other nonverbal gestures (see text for more details).

All participants were asked to perform two tasks: (a) seeking social approval (APR), and (b) avoiding social disapproval (AVOI), which were separated by run. There were six 6-minutes runs in total, three for each task type, following an event-related fMRI design, with intermixed incentive and control trials in each run. Before the onset of each run, participants were informed about the upcoming task type (APR or AVOI). Within a run, trial type was designated using intuitive cues: a plus sign for APR trials, the numeral zero for non-rewarded control (CON) trials, and a minus sign for AVOI trials, as shown in Fig. 1. APR and AVOI trials were never presented within the same run. Run type (AVOI or APR) was interleaved across runs and counterbalanced across participants. Each task consisted of a total of 48 incentive trials and 48 neutral control trials (in addition to 90 TR of null events).

The SID is a simple speeded button press task to examine anticipatory vs. consummatory neural responses to appetitive and aversive incentives that can be gained or avoided respectively dependent upon a person's ability to quickly and accurately respond to a target symbol. In APR trials, target hits resulted in a short video clip of a person showing happy facial expressions, including nodding with a smile and a praising nonverbal gesture – the “thumbs up” sign. The non-approval outcome for misses was a video clip of a person showing neutral expressions, with slight natural motion (e.g., eye blinks, some natural head sway). In AVOI trials, target hits resulted in avoiding disapproval with the outcome being a short video clip of someone with a neutral expression, whereas the disapproving outcome for misses was a video clip of a person frowning contemptuously and angrily along with shaking of the head and the “thumbs down” gesture. The outcome in the neutral CON condition was always a video clip of a person with closed eyes and neutral expression, pretending to listen to music while snapping their fingers (which controls for body movement in the social approval and disapproval clips). The video clips portrayed 48 different adult actors (half female, half male, of various races and ethnicities representative of the greater Philadelphia region); each of which was randomly repeated four times throughout the experiment. Identity of the actors did not overlap between the different incentive conditions. Videos were chosen from a larger pool based on ratings of the actor's likability as well as based on her authenticity of depicting approval and/or disapproval; only actors who had the highest ratings on both scales were included. Ratings were done by a separate group of healthy adults (N=44; mean age = 29.0). Study participants were not asked to rate the stimuli. Likability and authenticity ratings of actors were equal across the different task conditions (all ps ≥ 0.4).

The experimental design called for two-thirds of each trial type to have positive outcome, consistent with previous MID task designs. For each incentive trial, positive outcome was dependent upon the participants' ability to quickly press a button when the cued target (solid white square) appeared on the screen, within an experimentally controlled and defined time frame that was depicted via target duration. The time frame was individualized to ensure a comparable percentage of trials with positive outcome across conditions and across participants: The initial target duration for an incentive trial was estimated based on a reaction time experiment conducted in the lab prior to the MRI experiment (following the same experimental design as used during the scan, but without social incentives). From data on each participant, an initial time frame was determined so that participants might achieve the standardized hit rate of ∼66%. Moreover, in order to keep task difficulty constant throughout the experiment, an online tracking algorithm was used to continuously monitor and adjust target duration according to individual performance. Participant RT exceeded threshold an average of 61.0 ± 6.6% of the time on incentive trials (approximating the targeted 66% criterion), and an average of 51.6 ± 8.0% of the non-rewarded control trials; these rates are comparable to previous studies using monetary rewards (e.g.,(Knutson, Fong, et al., 2001)).

To ensure that participants fully understood the different cue-outcome associations, each participant received training prior to the scan, which was followed by a performancebased test of their understanding. In addition, study staff were instructed to not give praise to participants in-between runs to avoid social satiation effects, i.e., diminished responsivity to social incentives due to external, task-irrelevant social reinforcement (Gewirtz & Baer, 1958).

2.3. Image acquisition

All imaging data were collected using a Siemens Verio 3T scanner (Erlangen, Germany) and a 32 multichannel head coil. Functional data consisted of six 6-minute runs of whole-brain T2* weighted BOLD echoplanar images with 159 volumes acquired per run (40 oblique axial slices, isotropic voxel size = 3.5 mm, TR/TE = 2340/25 ms, flip angle = 90°). Two high-resolution structural MR images were acquired for the registration of fMRI data to MNI space: A T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence of the entire brain (176 sagittal slices, isotropic voxel size = 1 mm, TR/TE = 1900/2.54 ms, flip angle = 9°), and a FLASH sequence collected in the same plane as the fMRI data (number of slices = 40, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, TR/TE = 300/2.46 ms, flip angle = 60°).

2.4. Image analysis

Image processing and statistical analyses were carried out using FEAT v5.98 in the FSL (v4.1.4) analysis package (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Prior to image analysis, the first two images of each run were discarded because of the non-equilibrium state of magnetization. For pre-processing, functional volumes for each participant were skullstripped, motion-corrected, temporally high-pass filtered, and spatially smoothed using a Gaussian kernel (FWHM = 5 mm). Functional data were registered to MNI space using affine transformations using FLIRT.

FMRIB's Improved Linear Model with autocorrelation correction was used for regression analyses on the pre-processed functional time series for each participant. Motion parameters were entered as nuisance regressors (APR: absolute mean displacement = 0.14 mm ± 0.05 mm, AVOI: absolute mean displacement = 0.13 mm ± 0.05 mm). The first-level model for the within-run analyses of each task included regressors following a two (incentive: [APR vs. CON] or [AVOI vs. CON]) by two (phase: anticipation/ANT vs. outcome/OUT) by two (performance: hit vs. miss) design: ANT APR Hit, ANT APR Miss, ANT AVOI Hit, ANT AVOI Miss, ANT CON Hit, ANT CON Miss, OUT APR Hit, OUT APR Miss, OUT AVOI Hit, OUT AVOI Miss, OUT CON Hit, and OUT CON Miss. Importantly, hit and miss trials were modelled separately, as animal research has shown that VS/Nacc signals to reward-predicting cues are significantly greater when subsequent operant responses to the cues are accurate (i.e., hit) rather than inaccurate (i.e., miss) (Francois, Conway, Lowry, Tricklebank, & Gilmour, 2012; Nicola, Yun, Wakabayashi, & Fields, 2004). Regressors were convolved with a double-gamma hemodynamic response function along with its temporal derivative. Each regressor resulted in a voxelwise effect-size parameter estimate (β value) image reflecting the magnitude of brain activation associated with that regressor. In order to create comparisons of interest, β value images were contrasted. The anticipation phase model included the duration of the variable interval between cue onset and feedback onset (∼1-2 TR jittered). The outcome period was modelled with a 1500 ms duration following feedback onset. Intertrial intervals and null events served as a low-level (implicit) baseline. Although the central question addressed in this study concerned the anticipation phase, we also report the data for the outcome phase for the sake of completeness.

Second-level analyses (i.e., across-run, within-subject) employed a fixed-effects model, whereas third-level group inferential statistical analyses were carried out on each contrast of interest using FMRIB's Linear Analysis of Mixed Effects (FLAME 1+2). All Z statistical maps were cluster-corrected with a mean cluster threshold of Z > 2.3 and a wholebrain corrected cluster significance threshold of p ≤ 0.05 using Gaussian random field theory (Worsley, Evans, Marrett, & Neelin, 1992). In addition, to test our a priori hypothesis of greater signal changes in the Nacc during anticipated approval and avoidance of disapproval versus anticipated non-incentive, we performed region of interest (ROI) analyses within bilateral Nacc for the contrasts APR > CON and AVOI > CON. The Nacc was anatomically defined based on the Harvard-Oxford structural probabilistic atlas. We applied a family-wise error (FWE) corrected threshold of p ≤ 0.05 across this region using Randomise v2.1 (part of FSL). Since females and males did not show differential brain activation pattern using whole-brain cluster thresholding at p ≤ 0.05, results are presented for both sexes combined.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral task performance

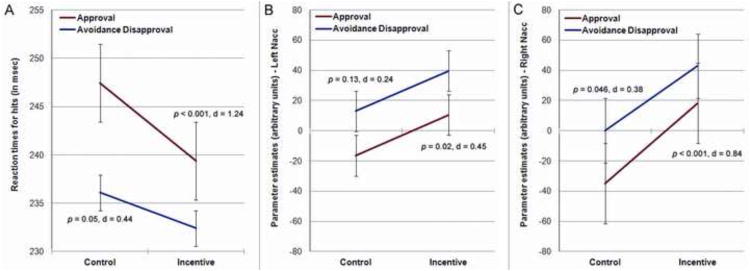

RT for hits were analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA with task (APR, AVOI) and trial (incentive, control) as the within-subjects factor in order to compare the incentive trials to the control trials within each task and across tasks. This analysis revealed a main effect of trial (F (1, 21) = 22.83, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.52), with faster RTs observed for incentive conditions relative to the neutral control condition (ps ≤ 0.05), suggesting that incentive manipulations within the experimental tasks were successful. We also found a main effect of task type (F (1, 21) = 14.88, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.42), with faster responses in the AVOI task than the APR task, and a significant trial by task interaction effect (F (1, 21) = 4.48, p = 0.046, η2p = 0.18), indicating that participants were faster in approval vs. control trials relative to avoiding disapproval vs. control trials (see Fig. 2).

Fig.2.

(A) Reaction times for hits (in msec) for the control and incentive conditions separately for the two social reward tasks. Participants responded faster during incentive trials relative to the control trials, with generally shorter RTs observed in the AVOI task than the APR task. A significant interaction effect emerged, indicating that participants decreased response speed to potential reward versus control more strongly when approval was at stake than under conditions of avoiding disapproval. (B) and (C) Mean parameter estimates extracted from our a priori ROIs – the left and right Nacc – during the anticipation phase (between cue onset and feedback onset) separately for the two social tasks. When entered into a repeated-measures ANOVA with task (APR, AVOI), trial (incentive, control) and hemisphere (left, right) as the within-subjects factors, a main effect of trial type (F (1, 21) = 7.67, p = 0.012, η2p = 0.27) and a trial by site interaction effect (F (1, 21) = 7.93, p = 0.010,,η2p = 0.27) emerged, reflecting greater Nacc activation for anticipated social approval and avoidance of disapproval versus control, particularly in the right hemisphere (right: p = 0.003; left: p = 0.068). The negative parameter estimates for control trials, particularly in the APR task, suggest that the non-incentive control trials might have been experienced as reward ‘omission’ leading to decreased activation in VS/Nacc. Error bars indicate ± 1.0 SEM.

3.2. Neuroimaging results

3.2.1. Anticipation of social approval

As expected the APR > CON contrast for the anticipation phase revealed significant activation in a cluster (k = 1465) comprising the ventral striatum, including Nacc (left: peak MNI = −10, 8, −4; Z = 3.41, right: peak MNI = 10, 8, −6; Z = 2.78) and ventromedial caudate (left: peak MNI = −10, 2, 8; Z = 4.02, right: peak MNI = 12, 14, 4; Z = 3.02), as well as dorsal striatum (i.e., right putamen: peak MNI = 28, −4, −4; Z = 3.14) and thalamus (left: peak MNI = −2, −14, 4; Z = 3.75, right: peak MNI = 2, −4, 8; Z = 3.33). The ROI analysis confirmed that the Nacc was more strongly activated during anticipation of social approval than during anticipation of the control feedback (right: k = 214, peak MNI = 4, 14, 0; t = 4.49), replicating earlier studies that applied static face images as social rewards (Rademacher et al., 2010; Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009).

3.2.2. Anticipated avoidance of social disapproval

The AVOI > CON contrast for the anticipation phase revealed significant activation in a cluster (k = 264) comprising the ventral striatum (left ventromedial caudate: peak MNI = −12, 10, −4; Z = 2.85, right: peak MNI = 10, 8, −2; Z = 3.64), dorsal striatum (left putamen: peak MNI = −24, 2, 2; Z = 3.71, right: peak MNI = 24, 4, −8; Z = 3.21) and thalamus (left: peak MNI = −14, −4, 10; Z = 3.65, right: peak MNI = 12, −6, 8; Z = 4.08), comparable to the findings for the APR > CON contrast. Thus, as predicted, the ROI analysis showed stronger Nacc activity during anticipation of avoiding social disapproval than during anticipation of the control outcome (left: k = 10, peak MNI = −14, 10, −4; t = 3.38, right: k = 13, peak MNI = 10, 6, 0; t = 4.02).

3.2.3. Direct comparison between anticipating social approval and avoiding social disapproval

No significant activation differences were found when the two high-level anticipation contrasts (i.e., APR > CON vs. AVOI > CON) were compared against each other using whole-brain cluster thresholding at p ≥ 0.05 and ROI analyses (Left Nacc: p = 0.68, d = 0.09; Right Nacc: p = 0.41, d = 0.18).

3.2.4. Direct comparison of control trials across incentive tasks

Given the behavioral finding of faster RTs for CON trials during AVOI vs. APR runs (236.1 vs. 247.4 msec; p < 0.001, η2p = 0.48), we also checked for potential brain activation differences in CON trials across the two social incentive tasks. Neither whole-brain cluster correction at p ≤ 0.05 nor ROI analyses revealed different activation pattern for the two CON conditions.

3.2.5. Between structure activation correlations for the anticipation phase

We explored across subjects the correlation between contrast estimate magnitudes from left and right Nacc separately for both APR > CON and AVOI > CON (Carter et al., 2009; Schlund & Cataldo, 2010). Results showed the expected strong association between left and right Nacc responses for both anticipated social approval (r = 0.76, p < 0.001) and anticipated avoidance of social disapproval (r = 0.88, p < 0.001). This suggests a high degree of consistency across neural signals from the right and left Nacc ROIs, thus enabling tests of other predicted relationships. However, the magnitude of Nacc activation varied substantially across participants (APR > CON: left Nacc β = 27.1 ± 59.6, right Nacc β = 52.9 ± 62.9; AVOI > CON: left Nacc β = 17.6 ± 87.6, right Nacc β = 33.7 ± 87.2), which is in line with previous reports on Nacc responses to monetary incentives (i.e., monetary gain vs. loss) (Carter et al., 2009). Thus, we next examined the extent to which Nacc activation correlated between anticipation of approval and avoiding disapproval (i.e., the correlation between APR > CON and AVOI > CON), but this relationship was not significantly different from zero (rs < −0.03, ns). Of note, ΔRT for hits (i.e., RT differences between incentive and control trials: APR vs. CON, AVOI vs. CON) were also not correlated (r = 0.18, ns). These RT and imaging results both suggest that there are large individual differences in the relative motivational value of social approval versus avoiding social disapproval reflected at the level of brain and behavior (Carlezon Jr. & Thomas, 2009; Ikemoto & Panksepp, 1999).

3.2.6. Brain-behavioral correlations

We found a significant negative correlation between Nacc activation magnitude differences to APR vs. CON and ΔRT for approval hits vs. control hits (right Nacc: r = −0.60, p = 0.004; left Nacc: r = −0.2, ns), which approached significance in the AVOI task (right Nacc: r = −0.35, p = 0.1; left Nacc: r = −0.28, ns). This suggests that stronger Nacc activation to anticipating social approval was associated with faster responses by the participants to attain this positive social outcome.

3.2.7. Outcome phase

Both high-level contrasts for the outcome phase (i.e., APR > CON, AVOI > CON) revealed brain responses in a cluster comprising the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and insula (right: peak MNI = 32, 16, −18; Z = 3.41, left: peak MNI = −40, 16, −10; Z = 3.76). Whole-brain analyses (clustered corrected at p ≤ 0.05) did not reveal signification activation differences during appraisal of approval and the successful avoidance of disapproval.

4. Discussion

In the present study using a newly developed set of ecologically valid social stimuli (i.e., video clips instead of static pictures), we could demonstrate that the anticipation of social punishment avoidance (i.e., disapproval) recruited the VS/Nacc circuitry in a manner that was similar to VS/Nacc activation during the anticipation of social reward gain (i.e., approval). Stronger VS/Nacc activity during anticipation of both types of social incentives was accompanied by faster reaction times of the participants to obtain those desired outcomes. Interestingly, though, correlational analyses suggest that within-subject VS/Nacc reactivity as well as behavioral responsivity to social incentives was differentially modulated depending on whether a potentially rewarding or an aversive and avoidable social encounter was expected. These individual differences in the relative perceived value of social reward and punishment conceivably might be stable attributes that could be characterized through more careful personality testing of study participants (e.g., reward dependency and harm avoidance (Caldu & Dreher, 2007; Falk et al., 2012; Yacubian & Büchel, 2009)).

These findings are consistent with and complement prior research in the non-social domain, which has shown VS/Nacc activation during anticipation of monetary gain and monetary loss avoidance (Carter et al., 2009; Delgado et al., 2009; Guitart-Masip et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2006; Stark et al., 2011; Tom et al., 2007). Thus, our data further support the bivalent activation pattern of the VS/Nacc, suggesting its involvement in coding the motivational salience of both anticipated positive stimuli like rewards as well as negative and aversive events such as punishments that humans usually strive to avoid. To subserve this role efficiently, the VS/Nacc does not act in isolation but is part of a functional ‘salience’ network, comprising numerous corticolimbic structures, which enable an organism to decide what to do (or not do) next (Seeley et al., 2007). Given the strong innervations by amygdala, insula, vmPFC, ACC and thalamus (see Supplementary Figure 1), which have all been found to signal the salience of positive and negative environmental stimuli (Haber & Knutson, 2010; Mobbs et al., 2009), the VS/Nacc is well-suited to function as the central hub within this circuit by translating motivational goals into action (Mogenson, Jones, & Yim, 1980).

Alternatively, but not mutually exclusively, it is also plausible that VS/Nacc activation, as found in this study, reflects prediction-errors signals trigged at onset of the sensory cues that were associated with the potential social outcome at stake (W. Schultz, Dayan, & Montague, 1997). Given the unpredictable stream of incentive and control trials across tasks, the continuous updating of the participant's expectation about the upcoming trial (e.g., better than expected) might have contributed to the VS/Nacc findings in the current study. However, this experiment was not designed to answer this question, which warrants further inquiry (Lin, Adolphs, & Rangel, 2012).

There has been a long-standing debate in the literature about the causes of avoidance behavior (see (Dinsmoor, 2001) and commentaries) and the potential contribution of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, independent of whether the avoidable punishment is social or non-social (Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010; Carlezon Jr. & Thomas, 2009; Horvitz, 2000; Ikemoto & Panksepp, 1999; Salamone, 1994). There is general agreement that the opportunity to actively avoid or remove aversive events (e.g., electric shocks, pain, monetary loss etc.) is inherently pleasurable, and thus may rely on dopaminergic reward circuitry, including VS/Nacc. During aversive situations, it has been argued that the major behavioral goal is wanting ‘safety’ (Ikemoto & Panksepp, 1999; Seymour et al., 2007), which – once achieved – functions as a reinforcement signal to strengthen the behavior that led to this positive outcome (Dinsmoor, 2001). To our knowledge, the results of this study show for the first time that this appears to also hold true for avoiding social punishment. Interestingly, the behavioral RT data indicate that participants were more motivated to avoid disapproval than to seek approval, suggesting that potential social punishment may loom larger than equivalent potential social reward, which would be consistent with predictions from Prospect theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

Furthermore, our data suggest individual differences in RT and VS/Nacc activity in response to anticipation of social reward gain and social punishment avoidance, consistent with previous findings that VS/Nacc responses vary as a function of subjective preferences for the specific reward at stake (e.g., different food items (Clithero, Reeck, Carter, Smith, & Huettel, 2011); social vs. monetary reward (Kohls, Peltzer, Herpertz-Dahlmann, & Konrad, 2009; Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009)). Within- or across-subject response variations to social reward gain and social punishment avoidance may well be related to differences in dopamine function (Knutson & Gibbs, 2007), which in turn could be related to personality dimensions such as reward dependency and harm avoidance (Caldu & Dreher, 2007; Falk et al., 2012; Yacubian & Büchel, 2009). Since our observation is based on correlational analyses, future studies will be needed to address this question more systematically (Carter et al., 2009). Nevertheless, evidence from animal research indicates that there may be functional variability within subregions of VS/Nacc regarding their responsivity to reward and punishment. Berridge and colleagues (Reynolds & Berridge, 2002, 2008), for instance, showed that Nacc subcompartments, organized along a rostro-caudal valence gradient, respond differently to appetitive versus aversive stimuli (e.g., sweet vs. bitter taste), possibly mediated by dopaminergic signals (Faure, Reynolds, Richard, & Berridge, 2008). As the current spatial resolution of human fMRI does not allow the reliable detection of such functionally segregated neural microcircuits within the VS/Nacc, other applications such as multivariate pattern analyses (MVPA) may better disentangle potentially dissociable patterns of brain activation evoked by anticipated social reward versus avoidance of social punishment (Clithero, Smith, Carter, & Huettel, 2011; Vickery, Chun, & Lee, 2011).

Given that the current study only included social incentives, our conclusions are restricted to the social domain and cannot simply be generalized to the non-social domain, including monetary incentives (i.e., money gain and money loss). This is particularly relevant, and should be followed-up in future investigations, since research suggests that the computation of both monetary and social incentives may recruit overlapping neural substrates (Lin et al., 2012; Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009).

It should be also noted that in our task design uninformative feedback was given for both hit and miss trials in the control condition, whereas in both social incentive conditions informative response contingencies were provided. Thus, it could be possible that the mere fact of having a feedback about task performance in the incentive conditions compared to the control baseline might have contributed, at least partially, to the findings reported here (but see (Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009)). Most importantly, though, it is unlikely that this possible bias fully accounts for the impact of social incentives on brain and behavior: Both approval and avoidance of disapproval served as social feedback, but influenced behavioral (e.g., RT for hits) and neural responses (e.g., correlational analyses) differently. However, future work is needed that apply, for instance, parametric task designs (e.g., low vs. high approval gain/disapproval avoidance) or implement a simple ‘success’ and ‘failure’ feedback component in the control condition in order to reveal a clearer picture about the Nacc involvement in socially motivated behaviors.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study may also have implications for clinical groups such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and social phobia (or “social anxiety disorder” (SAD)), which are characterized by symptoms alluded to aberrant social motivation (e.g., social withdrawal due to low appetitive motivation or high aversive motivations) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In the case of ASD, decreased social approach behavior is a salient behavioral feature, which presents as both reduced seeking and maintaining social relationships. Recent theories of ASD suggest that diminished social approach tendencies are related to a particularly low appetitive value assigned to social stimuli, mediated by dysfunction of the mesolimbic reward circuitry (Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005; R. T. Schultz, 2005). In fact, current imaging studies support those theories by demonstrating aberrant VS/Nacc activation in ASD in response to social rewards such as affirmative faces and praise (Kohls et al., 2011; Kohls, Schulte-Rüther, et al., 2012; Scott-Van Zeeland, Dapretto, Ghahremani, Poldrack, & Bookheimer, 2010) (reviewed in (Kohls, Chevallier, et al., 2012)). By contrast, a reduced inclination to initiate social interactions is also a central feature of social anxiety disorder (SAD) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which is, however, thought to primarily originate from an exaggerated salience assigned to aversive social events such as possible scrutiny or humiliation by others, which individuals with SAD excessively tend to avoid. Moreover, the enhanced salience of aversive events, like social evaluative threat or punishment, has been linked to dysfunction of the approach-avoidance circuitry, including the VS/Nacc (Britton, Lissek, Grillon, Norcross, & Pine, 2011; Helfinstein, Fox, & Pine, 2011; Shechner et al., 2012; Silk, Davis, McMakin, Dahl, & Forbes, 2012). Taken together, the lack of motivation for social encounters, as seen in ASD and SAD, can hypothetically arise from different inclinations – low social reward approach and/or high social punishment avoidance – with the VS/Nacc circuitry as the potential hub for both types of suboptimal social behavior (Falk et al., 2012; Vrtička & Vuilleumier, 2012). Thus, future ASD and SAD studies might employ a social incentive delay task in order to obtain deeper insights into the neural disruptions related to social motivation deficits in ASD versus SAD (Richey et al., 2012).

In conclusion, the results of the present study using social incentives (i.e., approval, avoidance of disapproval) corroborate and extend prior findings in the non-social domain (i.e., monetary gain, avoidance of monetary loss) by confirming the bivalent activation pattern of the VS/Nacc in response to both anticipated social reward gain and social punishment avoidance. However, the magnitudes of VS/Nacc responses varied substantially across participants, which likely reflect individual differences in responsivity to social reward versus social punishment. These important findings, if confirmed in follow-up studies, will increase our understanding of the brain-behavioral mechanisms underlying the typical motivation for social engagement and their disruption in neuropsychiatric disorders such as ASD and SAD.

Supplementary Material

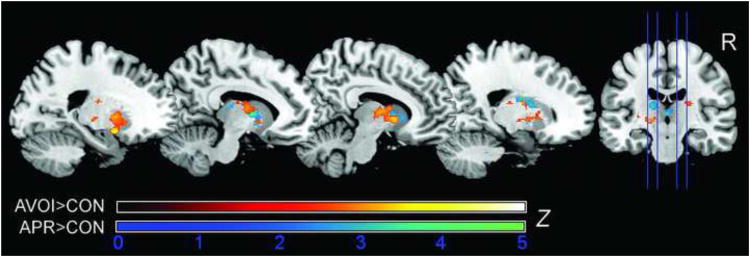

Fig.3.

Results of the whole-brain analyses for the two high-level anticipation contrasts (APR>CON and AVOI>CON) revealed significant activation in a cluster comprising ventral and dorsal striatum as well as thalamus. No significant activation differences were found when the two contrasts were compared against each other. Z scores are based on cluster-level correction for multiple comparisons across the whole brain with a mean cluster threshold of Z > 2.3 and a cluster-corrected significance threshold of p ≤ 0.05 using Gaussian random field theory (sagittal slices).

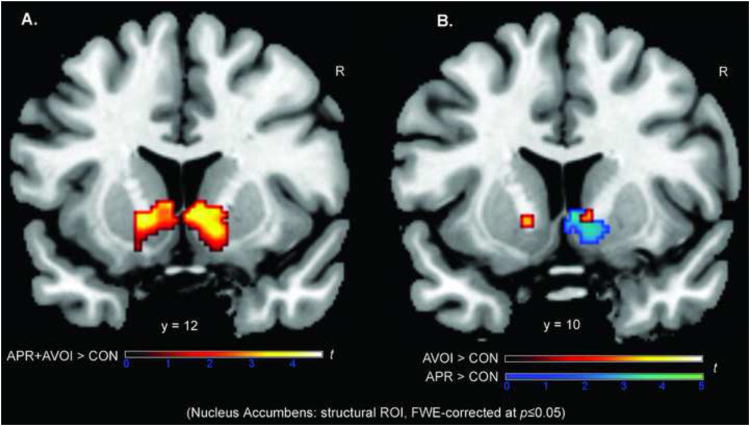

Fig.4.

To test our a priori hypothesis of greater signal changes in the Nacc during anticipated approval and avoidance of disapproval versus anticipated non-incentive control, we performed ROI analyses within bilateral Nacc for the contrasts APR>CON and AVOI>CON as well as for APR and AVOI combined vs. CON. The Nacc was anatomically defined based on the Harvard-Oxford structural probabilistic atlas. (A) Both social incentive conditions together revealed the expected strong bilateral Nacc activation (hot colors). (B) Results separately for the two contrasts of interest (i.e., APR>CON, AVOI>CON) showed that the prospect of avoiding social punishment (i.e., disapproval; hot colors) recruited the Nacc in a manner that was similar to Nacc activation during the seeking of social reward (i.e., approval; cool colors), particularly in the right hemisphere. ROI results are family wise error (FWE) corrected at p ≤ 0.05 (coronal slice).

Highlights.

The neural mechanisms of seeking social reward and avoiding social punishment were studied.

A ‘dynamic’ social incentive delay task was used to increase ecological validity.

Social punishment avoidance and social reward gain activated the nucleus accumbens.

Stronger nucleus accumbens reactivity was accompanied by faster reaction times.

Clinical implications for individuals with autism and social phobia are discussed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (#66727) to RTS and a NINDS Postdoctoral Award (T32NS007413) to SF.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Balliet D, Mulder LB, Van Lange PAM. Reward, punishment, and cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(4):594–615. doi: 10.1037/a0023489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing Reward. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003;26(9):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW. Dissecting components of reward: “liking”, “wanting”, and learning. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatter K, Schultz W. Rewarding properties of visual stimuli. Experimental Brain Research. 2006;168(4):541–546. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0114-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Lissek S, Grillon C, Norcross MA, Pine DS. Development of anxiety: the role of threat appraisal and fear learning. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(1):5–17. doi: 10.1002/da.20733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in Motivational Control: Rewarding, Aversive, and Alerting. Neuron. 2010;68(5):815–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH. Social rewards and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44(3):553–563. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.3.553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldu X, Dreher JC. Hormonal and Genetic Influences on Processing Reward and Social Information. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1118(1):43–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1412.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Thomas MJ. Biological substrates of reward and aversion: A nucleus accumbens activity hypothesis. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RM, MacInnes JJ, Huettel SA, Adcock RA. Activation in the VTA and nucleus accumbens increases in anticipation of both gains and losses. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:21. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.021.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(4):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clithero JA, Reeck C, Carter RM, Smith DV, Huettel SA. Nucleus Accumbens Mediates Relative Motivation for Rewards in the Absence of Choice. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2011;5:87. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clithero JA, Smith DV, Carter RM, Huettel SA. Within- and cross-participant classifiers reveal different neural coding of information. NeuroImage. 2011;56(2):699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Webb SJ, McPartland J. Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;27(3):403–424. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2703_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Jou RL, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA. Avoiding negative outcomes: tracking the mechanisms of avoidance learning in humans during fear conditioning. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:33. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.033.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Richey JA, Rittenberg AM, Sabatino A, Bodfish JW. Reward Circuitry Function in Autism During Face Anticipation and Outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(2):147–160. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1221-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinsmoor JA. Stimuli inevitably generated by behavior that avoids electric shock are inherently reinforcing. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;75(3):311–333. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.75-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk EB, Way BM, Jasinska AJ. An imaging genetics approach to understanding social influence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:168. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure A, Reynolds SM, Richard JM, Berridge KC. Mesolimbic Dopamine in Desire and Dread: Enabling Motivation to Be Generated by Localized Glutamate Disruptions in Nucleus Accumbens. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(28):7184–7192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4961-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox CJ, Iaria G, Barton JJS. Defining the face processing network: Optimization of the functional localizer in fMRI. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(5):1637–1651. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois J, Conway MW, Lowry JP, Tricklebank MD, Gilmour G. Changes in reward-related signals in the rat nucleus accumbens measured by in vivo oxygen amperometry are consistent with fMRI BOLD responses in man. NeuroImage. 2012;60(4):2169–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Frith U. Mechanisms of Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63(1):287–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasic GP, Smoller JW, Perlis RH, Sun M, Lee S, Kim BW, et al. Breiter HC. BDNF, relative preference, and reward circuitry responses to emotional communication. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2009;150B(6):762–781. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz JL, Baer DM. Deprivation and satiation of social reinforcers as drive conditions. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1958;57(2):165–172. doi: 10.1037/h0042880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitart-Masip M, Fuentemilla L, Bach DR, Huys QJM, Dayan P, Dolan RJ, Duzel E. Action Dominates Valence in Anticipatory Representations in the Human Striatum and Dopaminergic Midbrain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(21):7867–7875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6376-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfinstein SM, Fox NA, Pine DS. Approach-withdrawal and the role of the striatum in the temperament of behavioral inhibition. Developmental Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0026402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homans GC. Social Behavior as Exchange. American Journal of Sociology. 1958;63(6):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz J. Mesolimbocortical and nigrostriatal dopamine responses to salient non-reward events. Neuroscience. 2000;96(4):651–656. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Panksepp J. The role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in motivated behavior: a unifying interpretation with special reference to reward-seeking. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;31(1):6–41. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, McIntosh AR, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ, Remington G, Kapur S. Direct Activation of the Ventral Striatum in Anticipation of Aversive Stimuli. Neuron. 2003;40(6):1251–1257. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Shimojo S, O'Doherty JP. Is Avoiding an Aversive Outcome Rewarding? Neural Substrates of Avoidance Learning in the Human Brain. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(8):e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Adams CM, Fong GW, Hommer D. Anticipation of Increasing Monetary Reward Selectively Recruits Nucleus Accumbens. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(16):RC159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong G, Adams C, Varner J, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12(17):3683–3687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Gibbs SEB. Linking nucleus accumbens dopamine and blood oxygenation. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(3):813–822. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Taylor J, Kaufman M, Peterson R, Glover G. Distributed Neural Representation of Expected Value. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(19):4806–4812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0642-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Westdorp A, Kaiser E, Hommer D. FMRI Visualization of Brain Activity during a Monetary Incentive Delay Task. NeuroImage. 2000;12(1):20–27. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Chevallier C, Troiani V, Schultz RT. Social “wanting” dysfunction in autism: neurobiological underpinnings and treatment implications. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2012;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Peltzer J, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K. Differential effects of social and non-social reward on response inhibition in children and adolescents. Developmental Science. 2009;12(4):614–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Peltzer J, Schulte-Rüther M, Kamp-Becker I, Remschmidt H, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K. Atypical brain responses to reward cues in autism as revealed by event-related potentials. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(11):1523–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Schulte-Rüther M, Nehrkorn B, Müller K, Fink GR, Kamp-Becker I, Konrad K. Reward system dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1093/scan/nss033. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levita L, Hoskin R, Champi S. Avoidance of harm and anxiety: A role for the nucleus accumbens. NeuroImage. 2012;62(1):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Adolphs R, Rangel A. Social and monetary reward learning engage overlapping neural substrates. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2012;7(3):274–281. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Two types of dopamine neuron distinctly convey positive and negative motivational signals. Nature. 2009;459(7248):837–841. doi: 10.1038/nature08028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D, Marchant JL, Hassabis D, Seymour B, Tan G, Gray M, et al. Frith CD. From Threat to Fear: The Neural Organization of Defensive Fear Systems in Humans. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(39):12236–12243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2378-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogenson GJ, Jones DL, Yim CY. From motivation to action: Functional interface between the limbic system and the motor system. Progress in Neurobiology. 1980;14(2-3):69–97. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(80)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Yun IA, Wakabayashi KT, Fields HL. Cue-Evoked Firing of Nucleus Accumbens Neurons Encodes Motivational Significance During a Discriminative Stimulus Task. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;91(4):1840–1865. doi: 10.1152/jn.00657.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CMA, Groenewegen HJ, Lopes da Silva FH. The nucleus accumbens as a complex of functionally distinct neuronal ensembles: An integration of behavioural, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Progress in Neurobiology. 1994;42(6):719–761. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher L, Krach S, Kohls G, Irmak A, Gründer G, Spreckelmeyer KN. Dissociation of neural networks for anticipation and consumption of monetary and social rewards. NeuroImage. 2010;49(4):3276–3285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SM, Berridge KC. Positive and Negative Motivation in Nucleus Accumbens Shell: Bivalent Rostrocaudal Gradients for GABA-Elicited Eating, Taste “Liking”/“Disliking” Reactions, Place Preference/Avoidance, and Fear. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(16):7308–7320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07308.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SM, Berridge KC. Emotional environments retune the valence of appetitive versus fearful functions in nucleus accumbens. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11(4):423–425. doi: 10.1038/nn2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Plate RC, Plate RC, Ernst M. Neural systems underlying motivated behavior in adolescence: Implications for preventive medicine. Preventive Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey JA, Rittenberg A, Hughes L, Damiano CA, Sabatino A, Miller S, Dichter GS. Common and Distinct Neural Features of Social and Nonsocial Reward Processing in Autism and Social Anxiety Disorder. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1093/scan/nss146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling JK, Sanfey AG. The Neuroscience of Social Decision-Making. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62(1):23–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risko EF, Laidlaw KEW, Freeth M, Foulsham T, Kingstone A. Social attention with real versus reel stimuli: toward an empirical approach to concerns about ecological validity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:143. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DL, Zitzman DL, Williams SK. Mesolimbic dopamine transients in motivated behaviors: focus on maternal behavior. Frontiers in Child and Neurodevelopmental Psychiatry. 2011;2:23. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD. The involvement of nucleus accumbens dopamine in appetitive and aversive motivation. Behavioural Brain Research. 1994;61(2):117–133. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90153-8. doi:10.1016/0166- 4328(94)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato W, Yoshikawa S. Enhanced Experience of Emotional Arousal in Response to Dynamic Facial Expressions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2007;31(2):119–135. doi: 10.1007/s10919-007-0025-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlund MW, Cataldo MF. Amygdala involvement in human avoidance, escape and approach behavior. NeuroImage. 2010;53(2):769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Setlow B. Lesions of Nucleus Accumbens Disrupt Learning about Aversive Outcomes. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(30):9833–9841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09833.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Pilz K. Natural facial motion enhances cortical responses to faces. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;194(3):465–475. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1721-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RT. Developmental deficits in social perception in autism: the role of the amygdala and fusiform face area. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2005;23(2-3):125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275(5306):1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Dapretto M, Ghahremani DG, Poldrack RA, Bookheimer SY. Reward processing in autism. Autism Research. 2010;3(2):53–67. doi: 10.1002/aur.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Greicius MD. Dissociable Intrinsic Connectivity Networks for Salience Processing and Executive Control. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, O'Doherty JP, Koltzenburg M, Wiech K, Frackowiak R, Friston K, Dolan R. Opponent appetitive-aversive neural processes underlie predictive learning of pain relief. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(9):1234–1240. doi: 10.1038/nn1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, Singer T, Dolan R. The neurobiology of punishment. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(4):300–311. doi: 10.1038/nrn2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner T, Britton JC, Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, Ernst M, Fox NA, et al. Pine DS. Attention biases, anxiety, and development: toward or away from threats or rewards? Depression and anxiety. 2012;29(4):282–294. doi: 10.1002/da.20914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Davis S, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Forbes EE. Why do anxious children become depressed teenagers? The role of social evaluative threat and reward processing. Psychological Medicine. 2012:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DV, Hayden BY, Truong TK, Song AW, Platt ML, Huettel SA. Distinct Value Signals in Anterior and Posterior Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(7):2490–2495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3319-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreckelmeyer KN, Krach S, Kohls G, Rademacher L, Irmak A, Konrad K, et al. Gründer G. Anticipation of monetary and social reward differently activates mesolimbic brain structures in men and women. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4(2):158–165. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Bauer E, Merz CJ, Zimmermann M, Reuter M, Plichta MM, et al. Herrmann MJ. ADHD related behaviors are associated with brain activation in the reward system. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(3):426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom SM, Fox CR, Trepel C, Poldrack RA. The Neural Basis of Loss Aversion in Decision-Making Under Risk. Science. 2007;315(5811):515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.1134239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science. 1974;185(4157):1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickery TJ, Chun MM, Lee D. Ubiquity and Specificity of Reinforcement Signals throughout the Human Brain. Neuron. 2011;72(1):166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrtička P, Vuilleumier P. Neuroscience of human social interactions and adult attachment style. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:212. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ, Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P. A Three-Dimensional Statistical Analysis for CBF Activation Studies in Human Brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 1992;12(6):900–918. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacubian J, Büchel C. The genetic basis of individual differences in reward processing and the link to addictive behavior and social cognition. Neuroscience. 2009;164(1):55–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PT. The role of affective processes in learning and motivation. Psychological Review. 1959;66(2):104–125. doi: 10.1037/h0045997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.