Abstract

This study’s purpose was to examine the source, storage, preparation, and intake of food among Amish and non-Amish adults to understand dietary practices as a potential contributing factor to lower cancer incidence rates. Interviews were conducted with a random sample of 134 Amish and 154 non-Amish adults including questions about dietary practices and a 24-h dietary recall. Amish compared to non-Amish adults reported (1) less refrigeration in homes (85% vs. 100%, P < .01); (2) rarely/never obtaining food from restaurants and grocery stores (P < .01); (3) consuming less alcohol (P < .01); (4) consuming fewer daily servings of vegetables (males: 1.2 vs. 1.9 servings/day, P < .01; females: 1.0 vs. 2.1 servings/day, P < .01); and (5) a greater percentage of energy from saturated fat (males: 16.7% vs. 12.6%, P < .01; females: 16.3% vs. 12.0%, P < .01). Amish males reported greater amount of energy intake (2780 kcal vs. 2298 kcal, P = .03) compared to non-Amish males. Amish and non-Amish dietary patterns show some differences that may impact cancer although neither group achieves current diet and cancer prevention guidelines. Lifestyle factors, screening, and healthcare access may be contributing to the lower cancer incidence rates among the Amish and these results suggest areas of intervention to reduce the cancer burden.

INTRODUCTION

The Amish, a unique community in the United States, live mostly in the rural regions of the Midwestern states (1,2). Distinct characteristics of the Amish is their avoidance of modern day conveniences including electricity, automobiles, and the telephone (1,2). The agrarian lifestyle and cultural traditions of the Amish have changed modestly over recent years and have not been significantly influenced by the rapidly changing mainstream culture. Amish lifestyle factors, such as less use of tobacco products, have contributed to the significantly lower age-adjusted cancer incidence rates among the Amish (389.5 per 100,000) compared to non-Amish adults (646.9 per 100,000) living in Ohio (3,4). The lower cancer incidence rates among the Amish are worthy of note because the etiology of many cancers is multifaceted and several lifestyle factors (e.g., diet) may contribute to an individual’s risk for a specific cancer.

The relationship between dietary factors and cancer is complex because of interactions with other environmental and genetic risk factors that may uniquely contribute to cancer at each site. Current estimates are that nutrient intake and dietary habits contribute to over a third of all cancers globally (5,6). The dietary factors contributing to cancer risk include nutrient exposures, food preservation and cooking methods, and exposures to nonnutrient bioactive components in foods. Furthermore, development of improved dietary assessment tools that are relevant to different dietary variables and for different cultures is a major thrust of modern nutrition research (6,7). Despite these challenges, and a very limited number of controlled intervention trials, evidence-based guidelines for diet and cancer prevention have been established by several organizations (8–10).

Dietary practices including food production, processing, and consumption are components of the Amish culture that distinguishes them from their non-Amish neighbors (1,2). As a general rule, Amish cuisine is plain and rich in carbohydrates and lipids (1,2). Most Amish tend to have home gardens that provide fresh fruits and vegetables for seasonal consumption, as well as for canning, pickling, and storage for use during the winter months (1,2). Although these more conventional practices exist, the Amish occasionally purchase canned foods and shop in local supermarkets when convenient or necessary (1,2). Although no foods are prohibited in the Amish culture, alcohol consumption is strongly discouraged (1,2). Careful documentation of Amish dietary practices, with a focus on variables associated with cancer, has to our knowledge never been reported.

The purpose of this study was to compare food sources, storage, preparation methods, and food intake among the Amish and non-Amish living in Ohio Appalachia. We focused on the dietary components that are hypothesized to influence the risk of cancer, including fruits and vegetables, whole grains, dietary fiber, alcohol, various types of dietary fat, red meat, processed meat, nutrient exposures, food preservation, and energy excess. The results from this study may be used to generate hypotheses regarding potential diet–cancer relationships, which may explain the lower cancer incidence rates observed among the Amish in Ohio.

METHODS

Sample Population

This cross-sectional study consisted of Amish and non-Amish adults residing in the Holmes County, Ohio region. This region is the location of the largest Amish settlement in the world with over 220 Amish church districts (1,2). A random sample of Amish adults was selected from the 1996 Holmes County Amish Directory for a research study focusing on genetics (3). After introducing the cancer-related behavioral study in a mailed letter, a member of the research team personally visited each Amish residence to request study participation and to arrange an interview time. If the sampled individual no longer lived at the address, the current resident was recruited to participate in the study if they were Amish. To maintain the appropriate sample size, if the current resident was not Amish or if an Amish individual refused to participate, replacement households were randomly selected from the same church district listed in the Amish Directory. For the non-Amish, a random sample of adults was selected from enumerating residents who owned land in this region from the county auditors’ databases. As with the Amish sample, an introductory letter was mailed to the non-Amish residents and a member of the research team visited each residence to request study participation. The Ohio State University’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Collection

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 134 Amish adults and 154 non-Amish adults living in rural Ohio Appalachia during 2004 and 2005. If available, the male and female heads of households were both interviewed, and in the majority of cases completed the interviews in different rooms to avoid any potential reticence of response. The cancer-related behavioral lifestyle interviews took approximately 2 h to complete and each participant received a $25 gift card in appreciation of their time.

The diet section of the interview consisted of a 24-h diet recall using the multiple-pass approach, a method used to maximize accurate data collection (11). In addition, food models were used during the diet recall section of the interview to better estimate portion sizes. The interview also included questions that specifically assessed alcohol intake, as well as food storage, food preparation, and sources of food (self-produced, local Amish farms, restaurants, or grocery stores). Participants were also asked to complete a 3-day food diary that included 1 weekend day. The variables for food storage and preparation were measured at the household level. If only one person in the household was interviewed then he/she completed all of the household questions. In a household where both a male and female were interviewed, each answered a different set of questions for a subset of the food preparation and storage items. Within households, the males were asked about homemade sausages and slaughtered, smoked, and cured meat, whereas the women were asked about canning, pickling, sauerkraut, and storing fruits and vegetables over the winter.

To assess alcohol intake, we asked questions about current and past frequency, amount of alcohol consumed, and whether or not the respondent had ever been a binge drinker (large amounts of alcohol consumed in short periods of time). A drink was defined as a 12-oz beer, a 4-oz glass of wine, or 1 oz of liquor. Beverage models were used by the interviewers to obtain a more accurate account of portion size.

Food storage questions focused on the availability of an icebox, refrigerator, or freezer in the home, as well as the processing and storage of fruits and vegetables. Refrigeration use was evaluated with the following question, “What type of refrigeration do you use?” (responses: icebox/refrigerator/home freezer/rent space in a community freezer/other). To assess food storage, we asked the following question: “In the past year, did you store any raw fruits and vegetables over the winter?” (responses: yes/ no).

To assess food preparation, we examined the use and consumption of slaughtered, cured, and smoked meats, as well as homemade sausage and jerky by asking, “In the past year, have you slaughtered any of your own meats or had any slaughtered for you?” (responses: no/yes, within the past year/yes, but not within the past year). The questions were phrased similarly for cured meat, smoked meat, homemade sausages, and jerky. The participant was also asked about pickling, canning, sauerkraut preparation, milk pasteurization, growing fruits and vegetables within the past year, and the use of sprays and fertilizers for home grown foods (responses: yes/no).

To assess food procurement, we asked the participants how often their family ate food prepared by a restaurant or consumed meat, eggs, milk, cheese/butter, bread, fruit, and vegetables purchased from the grocery store (responses: never to daily).

Physical activity (total metabolic equivalents) was assessed by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short version (12), which aims to capture vigorous and moderate activity, walking, and time sitting during the past 7 days. As suggested by the IPAQ instructions, to make the questions more personally relevant, examples of vigorous physical activities provided to the participants were chopping wood, tossing straw bales, and so on. The participants were asked how many of the past 7 days were spent doing each physical activity and the average time spent doing that activity during those days.

At the end of the interview, participants were weighed using an electronic scale and their height was measured by a wooden, folding measuring stick. To reduce measurement error, weight and height were each measured twice and the average of each of the 2 measurements was used to calculate each individual’s body mass index.

Data Processing

The dietary intake data from the 24-h recalls were analyzed using Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) software version 2007, developed by the Nutrition Coordinating Center at the University of Minnesota. Data were entered consistently using established rules into NDS-R software and measures were in place for quality assurance. Data entry rules were derived from the NDS-R manual where a list was compiled and updated to maintain consistency in the data entry process. It was necessary to develop additional data entry rules in order to enhance the precision of the Amish data. For example, when an individual reported that they consumed milk from a cow, the data entry rules specified that this would be entered as whole milk.

For quality assurance, energy intake, expressed as total kilocalories (kcal), was examined on each record. Any individual record with energy intakes over 5,000 kcal or under 500 kcal in one day was examined very closely, as extremes may indicate that the record may have been inaccurate or that a data management error had occurred. As another quality assurance measure, summary reports comparing intake from individual records to recommended daily values for a 2,000-kcal diet were examined. If reported intake of any macronutrient was over 150% of the recommended daily value or if any micronutrient was more than 200% of the recommended daily value, an in-depth examination of the records was conducted for accuracy.

Data Analysis

Household Level Variables on Food Source, Storage and Preparation

Data from the cross-sectional questionnaire were used to examine food storage and preparation at the household level. Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were used to compare differences between the Amish and the non-Amish. An index was created to provide a summary score that reflected the extent to which food from the external environment was avoided. The components of the index included food consumed at a restaurant; and meat, eggs, milk, cheese/butter, bread, fruit, and vegetables purchased from the grocery store. All of the items were weighted equally with 1 point given when the response was “rarely” or “never,” otherwise a 0 was assigned. The total score of the index was calculated by summing these items.

Individual Level Variables for Nutritional Intake

The 24-h recall and questionnaire data were analyzed to examine selected individual nutrients and intake of food groups among the Amish and the non-Amish. Data from the 3-day food diaries were used for qualitative information only, but not used for quantitative analyses due to the inconsistent information on serving sizes, cooking methods, or additional details needed for accurate entry and analyses.

The categories of fruits and vegetables used for these analyses were the same as those used in the geographically and ethnically diverse European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (13). Lipid intake was defined as grams of total, saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats and also expressed as the percent of total calories from each type of fat in the diet.

Descriptive statistics were calculated; all of the dietary intake variables, except alcohol, were examined as continuous variables but were also analyzed as binary variables (based on the median) for ease of interpretation and to avoid any vulnerability due to potential outliers. Continuous data were modeled using a linear regression model, adjusting for age, physical activity (measured as total metabolic equivalents), and energy intake (kcal) as potential confounders. In the initial stages, formal assessment of confounding was explored, but because relevant confounders varied depending on what nutrient/food was being explored, it was decided to force the most clinically relevant and/or those variables that appeared to be confounders most frequently in all models. The alcohol variable was categorized into tertiles, with the groups being never drinker (in the past year), less than or equal to 1 drink/wk, and greater than 1 drink/wk. Chi-square analyses were conducted to compare alcohol differences among Amish and non-Amish adults.

Due to the fact that many times both the husband and the wife within a household were interviewed, the analyses were stratified by gender to avoid any issues that might arise with correlated data. Adjustments were not made for multiple comparisons because of the prespecified analyses plan and the intent of the research was exploratory in nature and not confirmatory. Analyses for both the individual-level and household-level data were performed using SAS version 9.0 software and procedures (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

An individual at each Amish home was contacted and the household response rate among the Amish was 67%. The response rate was 23% among the non-Amish; however, the agreement rate, which is the percentage of the individuals who completed the survey among those who were actually contacted, was 37% among the non-Amish.

Demographic characteristics for the participants are listed in Table 1. Amish males were younger than non-Amish males (P < .05), and a greater number of Amish males and females reported being married (P < .01) compared to non-Amish adults. The Amish were less likely to complete high school compared to non-Amish (P < .01) because by law, Amish children are only required to attend school through the 8th grade (1,2).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics among Amish and non-Amish participants by gender

| Males |

Females |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Amish (n = 58) | Non-Amish (n = 64) | Amish (n = 66) | Non-Amish (n = 90) |

| Age (yr): Mean (SD) | 52.4 (13.8) | 58.8 (15.9)* | 52.9 (15.1) | 56.8 (15.3) |

| Body mass index: Mean (SD) | 27.6 (4.6) | 29.4 (7.0) | 30.1 (6.0) | 29.2 (6.0) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 3.2% | 1.6% | 0% | 2.2% |

| Married | 95.2% | 82.5%** | 93.1% | 74.2%** |

| Divorced/separated | 0% | 14.3% | 0% | 9.0% |

| Widowed | 1.6% | 1.6% | 6.9% | 14.6% |

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 98.4% | 12.5%** | 100% | 12.2%** |

| High school degree | 1.6% | 46.9% | 0% | 52.2% |

| > High school degree | 0% | 40.6% | 0% | 35.6% |

P < .05

P < .01.

Household Data

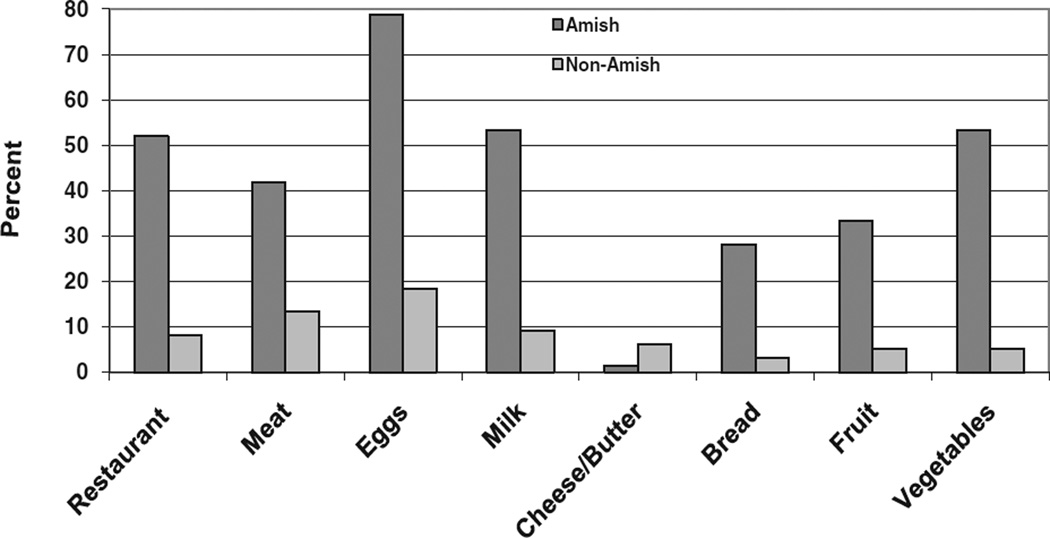

A total of 173 households (75 Amish and 98 non-Amish households) were included in the study. The variables that were examined to determine the extent of food consumed from the external environment, including restaurants and grocery stores are displayed in Fig. 1. A higher percentage of the Amish adults reported never or rarely consuming the listed foods from the external environment compared to the non-Amish adults. This was true for every variable except cheese and butter with approximately 1% of the Amish reported never or rarely eating cheese and butter from the grocery store compared to 6% of the non-Amish. The created index score, as described in Methods, showed a statistically significant difference (P < .01) in the median index scores between the Amish and the non-Amish suggesting that the Amish were significantly more likely to never/rarely obtain food from restaurants and grocery stores compared to the non-Amish (P < 0.0001).

FIG. 1.

Percentage of Amish and non-Amish households that never/rarely consume food from the external environment.

There were statistically significant differences between the Amish and the non-Amish for storage and preparation variables for most foods, with the exception of jerky (Table 2). Compared to the non-Amish, fewer Amish households reported having a refrigerator/freezer in their home. In fact, 13% of the Amish households had only an icebox in their homes and 1 Amish household reported not having a refrigerator, freezer, or icebox in the home. The Amish were significantly (P < .01) more likely to report storing fruits and vegetables over the winter; using milk not purchased in the grocery store; growing fruits and vegetables using fertilizer; slaughtering and smoking meats; and preserving food by canning and pickling.

TABLE 2.

Food storage and preparation among the Amish and non-Amish households

| Food storage and preparation | Amish (%) (n = 75) | Non-Amish (%) (n = 98) |

|---|---|---|

| Refrigeration (n = 173) | ||

| Icebox only/none | 11 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Refrigerator and/or freezer | 64 (85) | 98 (100)** |

| Fruits and vegetables stored raw over the winter (n = 173) | ||

| No | 11 (15) | 81 (83)** |

| Yes | 64 (85) | 17 (17) |

| Use milk that is purchased in stores (n = 172) | ||

| No | 46 (62) | 1 (1)** |

| Yes | 28 (38) | 97 (99) |

| If milk not purchased in the store, those who pasteurize the milk (n = 51†) | ||

| No | 46 (96) | 2 (67)* |

| Yes | 2 (4) | 1 (33) |

| Grow fruits and vegetables for household consumption (n = 173) | ||

| No | 2 (3) | 44 (45)** |

| Yes | 73 (97) | 54 (55) |

| If so, fertilizers applied to those fruits and vegetables (n = 127)¶ | ||

| No | 21 (29) | 33 (60)** |

| Yes | 51 (71) | 22 (40) |

| Slaughtered own meats or had them slaughtered for you (n = 170) | ||

| No | 5 (7) | 44 (45)** |

| Yes, within past year | 54 (74) | 22 (23) |

| Yes, but not within past year | 14 (19) | 31 (32) |

| Smoke/cure own meats or had them smoked/ cured for you (n = 168) | ||

| No | 31 (44) | 75 (77)** |

| Yes, within past year | 21 (30) | 8 (8) |

| Yes, but not within past year | 19 (26) | 14 (15) |

| Made own sausages or had them made for you (n = 169) | ||

| No | 21 (29) | 66 (68)** |

| Yes, within past year | 27 (38) | 15 (15) |

| Yes, but not within past year | 24 (33) | 16 (17) |

| Made own jerky or had it made for you (n = 169) |

||

| No | 55 (76) | 80 (83) |

| Yes, within past year | 8 (11) | 8 (8) |

| Yes, but not within past year | 9 (13) | 9 (9) |

| Canning by household (n = 173) | ||

| No | 2 (3) | 70 (71)** |

| Yes | 73 (97) | 28 (29) |

| Pickled anything in the past year (n = 173) | ||

| No | 22 (29) | 83 (85)** |

| Yes | 53 (71) | 15 (15) |

P < .05

P < .01

Sample for this question should be a subset of the individuals who do not purchase milk from the grocery store, although it appears that skip patterns in the questionnaire were not followed for some individuals.

Sample for this question is a subset of the individuals who grow fruits and vegetables for consumption at home.

Individual Level Data

Nutritional Intake for Males

A total of 62 Amish and 64 non-Amish males completed the questionnaire. Four Amish males did not complete the 24-hour recall because of time limitations. Alcohol consumption among Amish males was significantly lower compared to the non-Amish (P < .01) males. Approximately 55% of the Amish males reported drinking less than or equal to 1 alcoholic drink per wk, whereas 16% of the non-Amish males consumed 1 or fewer drinks per wk.

Amish males (Table 3) reported consuming significantly more energy (kcal) and percentage of kcals from saturated fat than the non-Amish males. The mean caloric intake among the Amish males was 2766 kcal compared to 2298 kcal reported by the non-Amish males (P = .03). Amish males consumed 4.1% more calories from saturated fat (P < .01) and 1.6% fewer calories from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (P < .01) than the non-Amish males. Fewer servings of vegetables, refined grains, soft drinks, and fruit drinks were reported by the Amish males (P < .01) compared to the non-Amish males, However, the Amish males reported consumption of more (P < .01) cakes, cookies, and pies (1.91 servings per day) compared to non-Amish Males (0.72 servings per day).

TABLE 3.

Dietary intake of Amish and non-Amish male participants

| Mean (SD) |

Median |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary intake | Amish (n = 58) | Non-Amish (n = 64) | Amish (n = 58) | Non-Amish (n = 64) | P value* |

| Energy and macronutrients | |||||

| Total energy (kcal/day) | 2766 (870) | 2298 (871) | 2560 | 2143 | .03** |

| Total fat (g) | 118.5 (49.0) | 95.4 (47.7) | 103.3 | 94.5 | .67 |

| % kcal from fat/day | 38.0 (8.6) | 36.8 (10.0) | 37.7 | 37.1 | .46** |

| Total protein (g) | 97.3 (42.6) | 87.7 (39.3) | 86.6 | 77.4 | .09 |

| % kcal from protein/day | 14.0 (3.8) | 15.4 (3.6) | 13.6 | 15.8 | .03** |

| Total carbohydrates (g) | 342.8 (121.6) | 274.7 (114.8) | 337.3 | 274.3 | .24 |

| % kcal from carbohydrate | 50.2 (10.5) | 48.1 (10.8) | 50.9 | 48.2 | .26** |

| Lipids | |||||

| Saturated fat (g/day) | 52.3 (24.1) | 32.8 (18.7) | 49.315 | 29.75 | <.01 |

| % kcal from saturated fat | 16.7 (4.7) | 12.6 (4.4) | 16.0 | 12.3 | <.01 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g/day) | 38.9 (15.7) | 36.2 (18.6) | 36.4 | 35.4 | <.05 |

| % kcal from monounsaturated fat | 12.6 (3.1) | 14.1 (4.4) | 12.4 | 13.9 | .08 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g/day) | 17.3 (10.7) | 18.5 (12.0) | 14.7 | 15.5 | <.01 |

| % kcal from polyunsaturated fat | 5.5 (2.9) | 7.1 (3.5) | 4.9 | 6.3 | <.01 |

| Polyunsaturated/saturated fat ratio | 0.36 (0.2) | 0.62 (0.4) | 0.3 | 0.5 | <.01 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g/day) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.4 | 1.2 | .95 |

| Trans fatty acids (g/day) | 5.9 (2.7) | 5.9 (4.2) | 5.2 | 4.2 | .11 |

| Carbohydrates, starches, and fiber | |||||

| Potatoes (serv/day) | 1.13 (1.40) | 0.69 (1.03) | 0.58 | 0 | .04 |

| Whole grain*** (serv/day) | 2.2 (2.4) | 1.6 (1.9) | 1.4 | 1.1 | .15 |

| Refined carbohydrates*** (serv/day) | 2.9 (2.2) | 4.2 (3.8) | 2.5 | 3.3 | <.01 |

| Total fiber (g/day) | 23.6 (10.6) | 19.3 (8.5) | 21.5 | 18.6 | .31 |

| Soluble fiber (g/day) | 6.7 (2.9) | 5.4 (2.4) | 6.5 | 5.0 | .41 |

| Insoluble fiber (g/day) | 16.7 (8.4) | 13.5 (6.6) | 14.0 | 12.6 | .26 |

| Soft drinks (8 fl oz serv/day) | 0.43 (0.87) | 0.80 (1.19) | 0 | 0 | <.01 |

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/day) | |||||

| Fruits | 2.6 (2.8) | 1.4 (3.4) | 2.0 | 0 | .10 |

| Citrus fruits | 0.05 (0.3) | 0.01 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | .52 |

| Non-citrus fruits | 2.6 (2.7) | 1.4 (3.3) | 2 | 0 | .09 |

| Vegetables | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.9) | 0.7 | 1.4 | <.01 |

| Dark green vegetables | 0.08 (0.4) | 0.11 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | .66 |

| Deep yellow vegetables | 0.12 (0.3) | 0.29 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | .25 |

| Tomato | 0.20 (0.5) | 0.61 (0.9) | 0 | 0.2755 | <.01 |

| Total fruits and vegetables | 3.8 (2.9) | 3.3 (3.6) | 3.2 | 2.6 | .89 |

| Milk and dairy (servings/day) | |||||

| All milk and dairy | 2.2 (1.5) | 1.6 (2.1) | 1.8 | 1.0 | .81 |

| Low-fat/fat free milk and dairy | 0.14 (0.5) | 0.70 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | .01 |

| Meat (servings/day) | |||||

| Red meat | 1.9 (3.0) | 2.2 (2.8) | 0 | 1.2 | .23 |

| Poultry | 0.89 (1.9) | 1.71 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | <.01 |

| Processed meat | 1.8 (2.1) | 1.3 (1.8) | 1.1 | 0.4 | .31 |

| Beef | 1.8 (3.1) | 1.7 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | .54 |

| Pork | 0.66 (1.3) | 0.78 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | .97 |

| Fish | 0.83 (3.0) | 0.09 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | .13 |

| Other food items (servings/day) | |||||

| Cakes/cookies/pies | 1.91 (2.0) | 0.72 (1.1) | 1.38 | 0 | <.01 |

| Pickled foods | 0.33 (0.9) | 0.15 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | .08 |

Adjusted for age, physical activity (total METS), and energy intake (kcal).

Adjusted for age and physical activity (total METS).

Flour, bread, crackers, pasta, cereal, snack bars.

Servings sizes are assigned to each food within NDSR based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans when available.

Nutritional Intake for Females

A total of 72 Amish and 90 non-Amish females completed the face-to-face interview. Only 66 Amish females completed the 24-h recall, reportedly due to lack of time, and 1 respondent appeared to be confused and thus the 24-hour recall was not completed.

Alcohol intake among Amish females was significantly lower than among non-Amish females (P < .01). The percentage of Amish females who were never drinkers was greater than non-Amish females (85% and 60%, respectively).

The total number of calories reported was not significantly different between the Amish and non-Amish females (Table 4), although the percentage of calories from saturated fat was 4.3% higher among the Amish (P < .01) and the percent of calories from PUFA was 1.9% lower among the Amish females (P < .01).

TABLE 4.

Dietary intake of Amish and non-Amish female participants

| Mean (SD) |

Median |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary intake | Amish (n = 66) | Non-Amish (n = 90) | Amish (n = 66) | Non-Amish (n = 90) | P value* |

| Energy and macronutrients | |||||

| Total energy (kcal/day) | 1901 (695) | 1785 (618) | 1754 | 1620 | .59** |

| Total fat (g) | 83.5 (38.4) | 73.9 (38.9) | 82.2 | 62.3 | .17 |

| % kcal from fat | 38.7 (8.5) | 36.4 (9.9) | 39.2 | 35.6 | .14** |

| Total protein (g) | 66.5 (27.9) | 65.8 (25.3) | 65.9 | 62.7 | .48 |

| % kcal from protein | 14.0 (4.2) | 15.3 (5.1) | 13.7 | 14.5 | 11** |

| Total carbohydrates (g) | 229.4 (87.5) | 219.4 (87.4) | 212.5 | 204.7 | .60 |

| % kcal from carbohydrate | 49.2 (11.7) | 49.6 (11.5) | 49.1 | 49.1 | .87** |

| Lipids | |||||

| Saturated fat (g/day) | 35.8 (19.8) | 24.7 (14.5) | 31.6 | 19.3 | <.01 |

| % kcal from saturated fat | 16.3 (4.4) | 12.0 (4.0) | 15.9 | 11.3 | <.01** |

| Monounsaturated fat (g/day) | 28.6 (13.2) | 27.7 (15.3) | 28.8 | 24.2 | .49 |

| % kcal from monounsaturated fat | 13.3 (3.5) | 13.7 (4.2) | 13.5 | 13.6 | .48** |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g/day) | 12.3 (6.9) | 15.7 (9.9) | 10.7 | 13.6 | <.01 |

| % kcal from polyunsaturated fat | 5.9 (3.1) | 7.8 (3.9) | 5.2 | 6.8 | <.01** |

| Polyunsaturated/saturated fat ratio | 0.40 (0.27) | 0.71 (0.4) | 0.34 | 0.59 | <.01 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g/day) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.1 | 1.1 | .18 |

| Trans fatty acids (g/day) | 4.4 (2.5) | 4.9 (3.1) | 4.3 | 4.4 | .06 |

| Carbohydrates, starches, and fiber | |||||

| Potatoes (serv/day) | 0.82 (1.1) | 0.76 (1.2) | 0.23 | 0 | .87 |

| Whole grain*** (serv/day) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.7 | 0 | <.05 |

| Refined carbohydrates*** (servings/day) | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.8 (2.1) | 2.2 | 2.5 | .18 |

| Total fiber (g/day) | 14.7 (6.2) | 15.5 (7.6) | 13.4 | 13.9 | .24 |

| Soluble fiber (g/day) | 4.3 (1.9) | 4.5 (2.2) | 4.3 | 4.0 | .28 |

| Insoluble fiber (g/day) | 10.2 (4.6) | 10.8 (5.8) | 9.7 | 9.2 | .28 |

| Soft drinks (8 fl oz serv/day) | 0.15 (0.35) | 0.83 (1.31) | 0 | 0 | <.01 |

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/day) | |||||

| Fruits | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.4 | 0.5 | .09 |

| Citrus fruits | 0.07 (0.35) | 0.10 (0.44) | 0 | 0 | .86 |

| Non-citrus fruits | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.1 | 0 | .07 |

| Vegetables | 1.0 (1.3) | 2.1 (2.0) | 0.5 | 1.5 | <.01 |

| Dark green vegetables | 0.02 (0.16) | 0.22 (0.62) | 0 | 0 | .01 |

| Deep yellow vegetables | 0.11 (0.28) | 0.22 (0.54) | 0 | 0 | .09 |

| Tomato | 0.19 (0.37) | 0.54 (1.0) | 0 | 0.1 | <.01 |

| Total fruits and vegetables | 2.6 (2.0) | 3.2 (2.8) | 2.2 | 2.6 | .13 |

| Milk and dairy (servings/day) | |||||

| All milk and dairy | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.2) | 2.2 | 2.6 | .13 |

| Low-fat/fat free milk and dairy | 0.18 (0.6) | 0.29 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | .02 |

| Meat (servings/day) | |||||

| Red meat | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.6 (3.0) | 0 | 0.03 | .41 |

| Poultry | 1.1 (2.2) | 1.4 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | .35 |

| Processed meat | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.5) | 0.3 | 0 | .61 |

| Beef | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | .89 |

| Pork | 0.79 (1.5) | 0.88 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | .69 |

| Fish | 0.22 (1.1) | 0.16 (0.87) | 0 | 0 | .97 |

| Other food items (servings/day) | |||||

| Cakes/cookies/pies | 1.17 (1.24) | 0.70 (1.10) | 1 | 0 | .04 |

| Pickled foods | 0.50 (1.25) | 0.06 (0.20) | 0 | 0 | <.01 |

Adjusted for age, physical activity (total METS), and energy intake (kcal).

Adjusted for age and physical activity (total METS).

Flour, bread, crackers, pasta, cereal, snack bars.

Servings sizes are assigned to each food within NDSR based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans when available.

Amish females consumed a greater number of servings of whole grains (P < .05), more pickled foods (P < .01), and more cakes, cookies, and pies (P = .04) compared to non-Amish females. However, Amish females consumed significantly fewer vegetable servings than the non-Amish females (P < .01), including fewer servings of dark green vegetables (P < .05) and tomatoes (P < .01). Amish females reported consuming significantly fewer daily servings of soft drinks and fruit drinks compared to non-Amish females (P < .01).

DISCUSSION

Our study provides insight into the dietary patterns of the Amish, which along with other lifestyle factors, health behaviors, and access to care will help us understand the unique patterns of cancer in this population, while suggesting opportunities for intervention to improve health. We show clear differences between the Amish and non-Amish adults in Ohio Appalachia with regards to diet and nutrition, yet neither group is meeting the recommendations for global cancer prevention. Indeed, our observations suggest that both groups could reduce cancer risk by education efforts that are culturally appropriate to enhance overall adherence to current dietary guidelines (9).

We observed many differences among Amish and non-Amish adults with respect to the source, preparation, storage, and intake of food. The Amish rarely procure food from the external environment such as grocery stores, with the exception of cheese and butter that seems to be purchased more extensively than other foods. A greater than 5-fold difference in reporting restaurants as a source of food between non-Amish (52%) and Amish (8%) emphasizes the self-sufficient and family-oriented meal patterns of the Amish compared to a national trend among Americans to consume more food outside of the home (14).

Amish men were found to consume a greater amount of energy than non-Amish men. Men in many Amish families typically engage in farming and manufacturing, which requires significant physical labor that may explain the higher caloric intake (1,2). In addition, we observed a greater percentage of energy derived from saturated fat and a lower percentage of energy from PUFA. This may in part be due to the higher amount of butter and shortening, and lower consumption of margarine and other oils reported by the Amish (data not shown).

The procurement, processing, and pattern of meat intake between the Amish and non-Amish were quite different, which is in part due to the need for methods of preservation that do not involve refrigeration. The Amish are more likely to consume meats from their own farm, with a significant percentage of the meat smoked or cured for storage or made into sausages.

Differences between Amish and non-Amish indicate the importance of milk and dairy products in the Amish diet, typical of a dairy farming-based community. Milk is purchased in stores by 99% of non-Amish compared to only 38% of the Amish, with the majority of Amish consuming non-pasteurized milk. Although there did not appear to be a significant difference in consumption of all milk and dairy products, the Amish reported consuming significantly fewer low-fat/fat-free milk and dairy servings.

Our findings indicate that the Amish typically grow a large proportion of their own fruits and vegetables, and use canning and pickling to preserve the foods over the winter months. Research suggests that the benefit from fruits and vegetables in overall cancer prevention is at an intake of approximately 400 g per day, which is approximately 5 servings a day (9,17), yet both the Amish and non-Amish reported consuming well below this recommendation. There is convincing evidence that alcohol consumption can increase the risk for certain cancers including breast, liver, esophagus, pharynx, larynx, and mouth cancer (17–20). The Amish reported consuming significantly less alcohol in comparison to the non-Amish. Over half of the Amish males (55%) reported consuming less than or equal to 1 drink per wk, whereas the majority of the Amish females (85%) reported never drinking.

To our knowledge, there are no other population-based reports describing food storage and preparation habits in the Amish community and population-based research examining the diet habits and patterns of the Amish is very limited. In the late 1980s, a systematic study was conducted in a random sample of 400 Amish adults to examine health behaviors using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey compared to non-Amish from the same area. Results indicated that the Amish had lower rates of alcohol consumption, were less likely to salt their food, and were more likely to take vitamin supplements than the non-Amish control group (21). Unpublished data from the early 1980s examined dietary intake by 24-h recall and meal patterns in 50 Old Order Amish and 50 non-Amish control group participants from an urban area (22). The study concluded that the Amish demonstrated more structured eating patterns than the urban control group, meaning a greater percentage of the Amish regularly consumed 3 meals a day with a snack before bed. It also appeared that total energy consumption and fat intake were greater among the Amish compared to the urban controls, which was very similar to what was found in the current research.

A major strength of this study was that information was collected by trained interviewers. In addition, the dietary data were entered by nutrition students trained to use NDS-R with quality assurance procedures in place. Limitations of this study include its modest size and low response rates among the non-Amish. The Amish were usually at home and refused to participate in the study because of the lack of time. We attempted to reach each household up to 3 times, however, the non-Amish were more difficult to contact in person to arrange interviews. Many individuals reported that they lacked time to participate in the study. Dietary assessment is always problematic, but we feel that in this study the 24-h recall provided the most reliable estimate of consumption. Completion of at least three 24-h recalls per subject would have been preferential, but not practical because all information had to be obtained from in-person interviews. We attempted to obtain 3-day food diaries; however, upon review, the data from this tool was unreliable due to the lack of information on serving sizes, detail of food types, and preparation of food, thus it was not used in the analyses. Quick clarification of the 3-day food diaries was not feasible among the Amish participants because they lack telephones. Although data from a single 24-h recall often underestimates dietary intake and is not an ideal measure of dietary patterns in a typical American population, the Amish diet may not vary as much from day to day. Our experience has provided insight that will assist in future investigations. In conclusion, the present work is the most comprehensive examination of the source, storage, preparation, and subsequent intake of food in the Amish community. We found that Amish dietary patterns do not meet most of the diet and cancer prevention guidelines published by American Institute for Cancer Research and others (9). Most cancer prevention guidelines emphasize minimizing calorically dense foods, eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables (at least 5 servings per day), avoiding salt-preserved foods, and limiting alcohol consumption. With the exception of limiting alcohol intake, our data suggest that the Amish do not meet these guidelines. It is therefore likely that other lifestyle factors (e.g., reduced tobacco use) may individually, or in combination with diet, explain the current difference in cancer incidence rates among the Amish and non-Amish living in Ohio. After taking into account the clear impact of tobacco (23), and the potential of screening differences (24), it appears the Amish and non-Amish in Ohio Appalachia exhibit a pattern of cancers that is consistent with Western culture and that both groups could benefit from dietary changes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH 1 P50CA015632, NIH 5 P30CA16058-31, K07 # CA 107079 (Mira L. Katz), and the Coleman Leukemia Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Gebra B. Cuyun Carter, College of Public Health, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Mira L. Katz, College of Public Health and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Amy K. Ferketich, College of Public Health and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Steven K. Clinton, College of Medicine and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Elizabeth M. Grainger, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Electra D. Paskett, College of Medicine and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Clara D. Bloomfield, College of Medicine and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Hostetler JA. Amish Society. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnermeyer JF, Kreps GM, Kreps MW. Lessons for Living: A Practical Approach to Daily Life From the Amish Community. Sugarcreek, Ohio: Carlisle Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westman JA, Ferketich AK, Kauffman RM, MacEachern SN, Wilkins JR, et al. Low cancer incidence rates in Ohio Amish. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9435-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferketich AK. Distribution of stage of disease among Amish and non-Amish living in Ohio. Columbus, OH: 2008. unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doll R, Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;66:1191–1308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willett WC. Diet, nutrition, and avoidable cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 8):165–170. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Block G. Human dietary assessment: methods and issues. Prev Med. 1989;18:653–660. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56:254–281. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. quiz 313–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Institute of Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 6th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RK. Dietary intake—how do we measure what people are really eating? Obes Res. 2002;10(Suppl 1):63S–68S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IPAQ Core Group. IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire, Short Format. 2001 http://www.ipaq.ki.se/ipaq.htm.

- 13.Agudo A, Slimani N, Ocke MC, Naska A, Miller AB, et al. Consumption of vegetables, fruit and other plant foods in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohorts from 10 European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6B):1179–1196. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: changes and consequences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.English DR, MacInnis RJ, Hodge AM, Hopper JL, Haydon AM, et al. Red meat, chicken, and fish consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1509–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norat T, Bingham S, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Jenab M, et al. Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:906–916. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Key TJ, Schatzkin A, Willett WC, Allen NC, Spencer EA, et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(1A):187–200. doi: 10.1079/phn2003588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, France: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1988. p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Toxicology Program, United States Public Health Service. Annual Report on Carcinogens. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riboli E, Lambert R, editors. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Nutrition and Lifestyle: Opportunities for Cancer Prevention. Lyon, France: IARC Scientific Publications, No. 156. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinson RM, Fuchs JA, Stoddard RR, Jones DH, Mullet M. Behavioral risk factors in an Amish community. Amer J Prev Med. 1989;5:150–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weale VW. Eating Patterns and Food Energy and Nutrient Intake of Old Order Amish in Holmes County, Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University Libraries; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferketich AK, Katz ML, Kauffman RM, Paskett ED, Lemeshow S, et al. Tobacco use among the Amish in Holmes County, Ohio. J Rural Health. 2008;24:84–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz ML, Ferketich AK, Paskett ED, Harley A, Reiter PL, et al. Cancer screening practices among Amish and non-Amish adults living in Ohio Appalachia. J Rural Health. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00345.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]