Abstract

Concern over health risks is the most common motivation for quitting smoking. Health warnings on tobacco packages are among the most prominent interventions to convey the health risks of smoking. Face-to-face surveys were conducted in Mexico (n=1,072), and a web-based survey was conducted in the US (n=1,449) to examine the efficacy of health warning labels on health beliefs. Respondents were randomly assigned to view two sets of health warnings (each with one text-only warning and 5–6 pictorial warnings) for two different health effects. Respondents were asked whether they believed smoking caused 12 different health effects. Overall, the findings indicate high levels of health knowledge in both countries for some health effects, although significant knowledge gaps remained; for example: less than half of respondents agreed that smoking causes impotence and less than one third agreed that smoking causes gangrene. Mexican respondents endorsed a greater number of correct beliefs about the health impact of smoking than the US sample. In both countries, viewing related health warning labels increased beliefs about the health risks of smoking, particularly for less well-known health effects, such as gangrene, impotence, and stroke.

Worldwide, tobacco use remains the leading preventable cause of death (WHO, 2008a). Smoking-related diseases, including respiratory diseases, various forms of cancer, and cardiovascular disease, account for more than 5 million deaths per year. It is estimated that this number will rise to 8 million by 2030, if current patterns remain unchanged.

Concern about the health risks of smoking is among the most common motivations to quit among current and former smokers (Curry, Grothaus, & McBride, 1997; Hammond, McDonald, Fong, Brown, & Cameron, 2004; Hyland, Li, Bauer, Giovino, Steger, & Cummings, 2004). Previous studies have demonstrated that smokers with greater knowledge of the health risks of smoking were more likely to intend to quit and were more successful in their quit attempts (Nourjah, Wagener, Eberhardt, & Horowitz, 1994; Romer & Jamieson, 2001). Although it is generally assumed that smokers are well aware of the health risks associated with smoking and tobacco use, significant gaps in health knowledge remain, even in high-income countries such as Canada and the United States (US) (Health Canada, 2000; Hammond, Fong, McNeill, Borland, & Cummings, 2006). Risk perceptions are lower in most low-or middle-income countries (LMICs), which are characterized by limited access to health information, less exposure to mass media campaigns, and lower literacy levels (WHO, 2008b).

Communicating the health effects of smoking remains a primary objective for tobacco control. Health warnings on cigarette packages are an excellent medium for communicating health information given their reach and frequency of exposure, both at the point of purchase and at the time of smoking behaviour. Findings from both experimental and population-based studies have demonstrated that pictorial health warnings are more likely to be noticed and read by smokers than text-only warnings, and they are associated with greater motivation to quit smoking (Hammond, 2011).

Despite the evidence demonstrating a consistent association between health knowledge and smoking cessation, few studies have examined the influence of pictorial health warning labels directly on health knowledge. Further, most of this research has been conducted in high-income countries and it is unknown whether these findings would apply to LMICs. For example, graphic pictures of disease may violate cultural norms or simply prove to be too offensive in populations with little or no exposure to strong health communications. Cultural groups also vary in their focus on different organ systems as responsible for illness, as well as in the anxiety that they associate with different kinds of bodily symptoms (Good & Good, 1981; McElroy & Jezewski, 2003). For example, graphic pictures of disease may violate cultural norms or simply prove to be too offensive in populations with little or no exposure to strong health communications. As a result, the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings may differ with respect to the type of health effect they communicate.

The current study examined the efficacy of health warning labels on health beliefs among samples of adults and youth in the US and Mexico. At the time this study was conducted, text-only warnings appeared on cigarette packages in both countries. In Mexico, text-only warnings covered 50% of the back of cigarette packages, and included the following three messages that have remained the same since 2004: 1) “Smoking causes cancer and emphysema”, 2) “Quitting smoking reduces significant health risks”, and 3) “Smoking during pregnancy increases risk of premature birth and low birth weight babies”. US labelling policy requires that text-only warnings cover one side panel of cigarette packages, and include the following four messages that have remained the same since 1984: 1) “Surgeon General’s warning: Smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and may complicate pregnancy”, 2) “Quitting smoking now greatly reduces serious risks to your health”, 3) “Smoking by pregnant women may result in fetal injury, premature birth, and low birth weight”, and 4) “Cigarette smoke contains carbon monoxide”. The study sought to: 1) assess knowledge that smoking causes death, lung cancer, throat cancer, emphysema, mouth cancer, heart disease, harm to unborn babies, wrinkling and aging of skin, stroke, lung cancer from second-hand smoke exposure, impotence in male smokers, and gangrene; 2) determine whether health warnings increase health knowledge that is specific to warning label content; 3) determine the extent to which health beliefs differ by socioeconomic and individual-level factors, such as gender, age, education, and ethnicity; and 4) examine potential country-level differences in health knowledge and effects of warnings between the US and Mexico.

METHODS

In Mexico, face-to-face surveys were conducted between June and August 2010 using computer-assisted personal interviewing. Respondents were recruited using a standardized “intercept” technique (Sudman, 1980), whereby people were counted as they passed a geographical landmark and every 3rd individual was approached by a trained interviewer. Study sites included two public parks, a bus terminal, and outside five WalMart stores in Mexico City. Respondents were given a 50-peso phone card (equivalent to ~$4 USD) as a token of appreciation.

In the US, a web-based survey was conducted in December 2010. Respondents were recruited via email from a consumer panel maintained by Global Market Institute (GMI), with a panel reach of more than 2.8 million individuals. Respondents received points from GMI (equivalent to ~$3 USD) in appreciation of their time. Additional panel details can be found at: http://www.gmi-mr.com/.

All respondents were at least 16 years of age. Two groups of people were recruited for the study: 1) adult (age 19 and older) smokers, and 2) youth (age 16–18), including both smokers and non-smokers. Prior to beginning the interview, all respondents were provided with information about the study and asked to provide verbal consent (in Mexico), or by clicking a box on-screen (in the US). No personal information identifiers were collected; respondents remained anonymous. The study was reviewed by and received ethics clearance from the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo.

Protocol

After completing questions on socio-demographics and smoking behaviour, participants viewed a series of health warnings. Each respondent was randomly assigned to view two of 15 “sets” of health warnings, each for a different health effect of smoking (note that the Mexico study included an additional two sets of warnings on tobacco smoke constituents that are not reported in the current paper). Each “set” included 5–7 warnings on the same health effect, in a variety of executional styles. These included a text-only warning, as well as a variety of approaches to pictorial warnings, including graphic health effects (i.e., physical impact on the body), “lived experience” (i.e., individual suffering the consequences of smoking), symbolic (i.e., metaphorical representation of risk), or other popular approaches used in other countries. The text used in the warnings was the same for each warning within a particular set, with the exception of the testimonials. Testimonials featured the same picture as one of the “lived experience” warnings, but with a brief narrative describing a personal aspect of the same content, written as a quote from a person in the image, whose name and age were also included.

After viewing health warnings, respondents were asked whether they believed that smoking causes the following 12 health effects: lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, mouth cancer, throat cancer, emphysema, gangrene, impotence in male smokers, wrinkling and aging of the skin, death, harm to unborn babies, lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke. Warnings were kept as similar as possible across countries, but were adapted for local use. Adaptation of the warnings included: 1) translation into the local language, 2) use of racially appropriate models in images, where relevant and possible, and 3) locally-appropriate names for the testimonials. All local versions of the warnings were checked by the local research team for appropriateness. All warnings included in the study can be viewed at http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/study.

MEASURES

Demographics

Demographic variables included gender, age, education level, income level, and ethnicity. In Mexico, adult education level was categorized as ‘Low’ (Primary, Middle, Technical/vocational school, or less), ‘Moderate’ (Highschool or some university), or ‘High’ (University degree or higher). In the US, adult education level was categorized as ‘Low’ (Highschool or less), ‘Moderate’ (Technical/trade school or community college, or some university), and ‘High’ (University degree or higher). Income, collected only for US respondents, was categorized as ‘Low’ (under $30,000), ‘Moderate’ ($30,000 to $59,999), or ‘High’ ($60,000 and over). Ethnicity also collected only for US respondents, was categorized as ‘Minority’ (included Black or African-American, Hispanic or Latino, Asian or Pacific-Islander, Native American Indian, Mixed race, and Other) or ‘Non-minority’ (White).

Smoking behaviour

Respondents were asked about their smoking behaviour, including smoking frequency and quit intentions. To assess smoking frequency, respondents were asked “In the last 30 days, how often did you smoke cigarettes?” Those who responded ‘Every day’ were categorized as ‘daily smokers’, those who responded with ‘At least once a week’ or ‘At least once in the last month’ were categorized as ‘non-daily smokers’, and ‘non-smokers’ were those who responded with ‘Not at all’. Adult samples in both the US and Mexico did not include ‘non-smokers’. To assess quit intentions, adult and youth smokers were asked “Are you planning to quit… 1)’Within the next month’, 2)’Within the next 6 months’, 3)’Sometime in the future, beyond 6 months’, or 4)’Not planning to quit’. Response options were dichotomized into 0= ‘Not planning to quit’ and 1= ‘Planning to quit’ (which included the first three options).

Health beliefs

After presentation of the health warnings, respondents were prompted with the following in Mexico “I am going to read you a list of health effects and diseases that may or may not be caused by smoking cigarettes. Based on what you know or believe, does smoking cause…[lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, mouth cancer, throat cancer, emphysema, gangrene, impotence in male smokers, wrinkling and aging of the skin, death, harm to unborn babies, lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke]”. This was worded differently in the US because of the self-complete web-based survey design “You will now be presented with a list of …” Response options included ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Don’t Know’, and were dichotomized as follows: 0=‘No’ and ‘Don’t Know’; 1=‘Yes’.

A Health Belief Index (HBI) was created to measure respondents’ level of health knowledge. The index was calculated based on the number of correct health beliefs each participant endorsed for the 12 health effects presented in the study (range =0 to 12). Higher values correspond to higher levels of health knowledge. Lastly, a variable was created to capture whether respondents had viewed the set of health warnings specific to one of the twelve health effects presented in the study (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0. Logistic regression models were conducted to examine correlates of health belief outcomes for each of the twelve health effects caused by smoking: lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, mouth cancer, throat cancer, emphysema, gangrene, impotence in male smokers, wrinkling and aging of skin, death, harm to unborn babies, and lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke. A standard set of covariates was included in the regression models for adults: age (continuous), gender, smoking status (daily vs. non-daily), education, income (US only), and ethnicity (US only). Covariates in the youth regression model(s) included age (continuous), gender, and smoking status (non-smoker, daily smoker, non-daily smoker). Linear regression models were conducted to examine the influence of potential predictors of health knowledge using the Health Belief Index scale as the outcome.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of adults and youth from the US and Mexico included in the current analysis. The total sample consisted of 544 adult smokers and 528 youth in Mexico City, and 772 adult smokers and 677 youth from the US.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| CHARACTERISTICS | MEXICO % (n) | UNITED STATES % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADULTS (n=544) | YOUTH (n=528) | OVERALL (n=1,072) | ADULTS (n=772) | YOUTH (n=677) | OVERALL (n=1,449) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 51.7 (281) | 50.0 (264) | 50.8 (545) | 47.3 (365) | 53.3 (361) | 50.1 (726) |

| Female | 48.3 (263) | 50.0 (264) | 49.2 (527) | 52.7 (407) | 46.7 (316) | 49.9 (723) |

| Age (mean) | 29.3 | 16.9 | 23.2 | 47.2 | 16.7 | 32.9 |

| (SD=11.6) | (SD=0.9) | (SD=10.3) | (SD=12.5) | (SD=0.7) | (SD=17.7) | |

| Education levela | ||||||

| Low | 18.2 (99) | -- | 18.2 (99) | 28.0 (216) | -- | 28.0 (216) |

| Moderate | 51.9 (262) | -- | 51.9 (262) | 41.3 (319) | -- | 41.3 (319) |

| High | 29.8 (162) | -- | 29.8 (162) | 30.7 (237) | -- | 30.7 (237) |

| Income (annual net household) | ||||||

| Low (less than $30,000) | -- | -- | -- | 26.6 (203) | -- | 26.6 (203) |

| Moderate ($30,000 to $59,999) | -- | -- | -- | 36.2 (276) | -- | 36.2 (276) |

| High ($60,000 and over) | -- | -- | -- | 37.1 (283) | -- | 37.1 (283) |

| Smoking frequency | ||||||

| Daily | 51.7 (281) | 12.9 (68) | 32.6 (349) | 88.1 (680) | 12.1 (82) | 52.6 (762) |

| Non-daily | 48.3 (263) | 36.0 (190) | 42.3 (453) | 11.9 (92) | 19.4 (131) | 15.4 (223) |

| Non-smoker | 0 | 51.1 (270) | 25.2 (270) | 0 | 68.5 (464) | 32.0 (464) |

| Quit Intentions | ||||||

| Not planning to quit | 45.4 (247) | 35.3 (91) | 42.1 (338) | 20.9 (156) | 20.0 (41) | 20.7 (197) |

| Planning to quit | 54.6 (297) | 64.7 (167) | 57.9 (464) | 79.1 (589) | 80.0 (164) | 79.3 (753) |

| Ethnicity | -- | -- | -- | |||

| Non-minority | -- | -- | -- | 83.4 (644) | 75.5 (511) | 79.7 (1,155) |

| Minorityb | -- | -- | -- | 16.5 (127) | 24.4 (165) | 20.2 (292) |

Low=Highschool or less (US), Primary, Middle, or Technical/vocational school or less (Mexico); Moderate= Technical/trade school or community college or some university (US), Highschool or some university (Mexico); High=University or Post graduate degree (US, Mexico)

Minority includes: Black or African-American, Hispanic or Latino, Asian or Pacific-Islander, Native American Indian, Mixed race, and Other

--No data

Levels of health knowledge after viewing non-targeted health warning labels

Table 2 presents the proportion of respondents who believe smoking causes each of 12 health effects only among those who had not viewed the health warnings to the health effect in question. In both the US and Mexico, beliefs about the risks of lung cancer were high (86% to 99%); however, less than half agreed that smoking causes male impotence, and less than one third that smoking causes gangrene.

Table 2.

Percentage of respondents who believe smoking causes various health effectsa

| Based on what you know or believe, does smoking cause… | MEXICO | UNITED STATES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (n=443) | Youth† (n=450) | Overall (n=893) | Adults (n=667) | Youth† (n=590) | Overall* (n=1,257) | |

| Lung cancer? | 99.3% | 98.9% | 99.1% | 86.1% | 94.7%† | 90.1%* |

| Heart disease? | 85.1% | 73.2%† | 79.1% | 76.8% | 79.4% | 79.4% |

| Stroke? | 43.2% | 30.1%† | 36.6% | 61.7% | 65.3% | 63.4%* |

| Mouth cancer? | 79.2% | 74.2% | 76.7% | 78.1% | 84.1%† | 80.9%* |

| Throat cancer? | 92.8% | 85.7%† | 89.2% | 83.7% | 89.6%† | 86.5% |

| Emphysema? | 93.5% | 85.9%† | 89.7% | 88.5% | 80.5%† | 84.8%* |

| Gangrene? | 27.1% | 24.7% | 25.9% | 13.7% | 20.3%† | 16.8%* |

| Impotence in male smokers? | 56.9% | 41.2%† | 49.0% | 25.9% | 29.1% | 27.4%* |

| Wrinkling and aging of the skin? | 71.2% | 61.5%† | 66.3% | 73.8% | 76.6% | 75.1%* |

| Death? | 96.4% | 96.2% | 96.3% | 79.9% | 91.1%† | 85.1%* |

| Harm to unborn babies? | 97.1% | 96.7% | 96.9% | 75.5% | 87.4%† | 81.0%* |

| Lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke? | 89.4% | 84.7%† | 87.1% | 51.1% | 75.1%† | 62.4%* |

Data are shown only from respondents who did not view the health warnings specific to the health effect listed. Within this population, logistic regression models were conducted for each health effect to examine whether beliefs differed by age group (youth vs. adults) and by country (Mexico vs. US).

% responding ‘Yes’; remainder include ‘No’ and ‘Don’t Know’ responses.

Significant differences between adults and youth within each country, where p<.05

Significant differences “overall” between Mexico and the United States, where p<.05

Differences between adults and youth

Chi-square tests were conducted for Mexico and the US to examine age group (Adult vs. Youth) as a predictor for each of the 12 health belief outcomes. In the US, youth reported significantly higher levels of health knowledge than adults for 7 of the 12 health effects listed in Table 2: lung cancer, mouth cancer, throat cancer, gangrene, death, harm to unborn babies, and lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke. Adults were more likely than youth to believe that smoking causes just one of the health effects: emphysema. In contrast, adults in Mexico were more likely than youth to endorse 7 of the 12 health effects of smoking: heart disease, stroke, throat cancer, emphysema, impotence in male smokers, wrinkling and aging of the skin, and lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke.

Differences between the US and Mexico

A chi-square analysis including youth and adults from Mexico and the US was conducted to examine country differences for each of the 12 health belief outcomes. Significant differences between the US and Mexico were observed for 10 of the 12 health beliefs. Mexican respondents were significantly more likely to endorse 7 of the 10 health effects, including: lung cancer, emphysema, gangrene, impotence in male smokers, death, harm to unborn babies, and lung cancer in non-smokers from breathing cigarette smoke. US respondents were more likely to believe that smoking causes: stroke, mouth cancer, and wrinkling and aging of the skin.

Levels of health knowledge after viewing targeted health warning labels

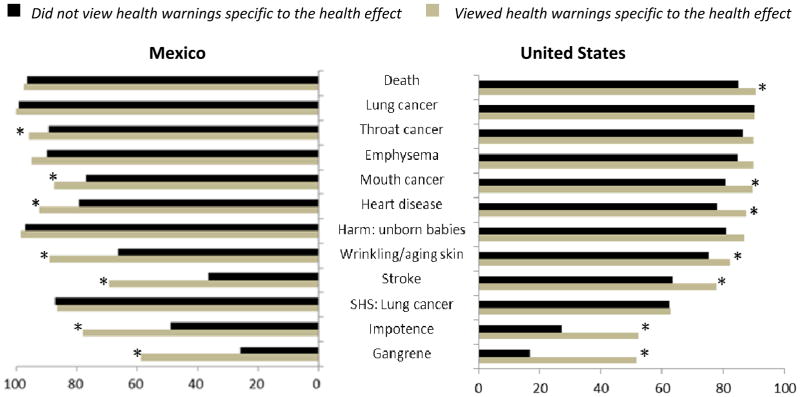

Chi-square tests were conducted for each health effect, separately by country, to examine whether health beliefs differed between respondents who had viewed the health warning labels targeted to that health effect, and those who had not (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents who believe smoking causes various health effects, by health warnings viewed. *Significant differences (p<.05) between those who did vs. did not the health warnings specific to the health effect

In the US, those who viewed the relevant warning set were more likely to endorse 7 of the 12 health effects relative to those who had not viewed the relevant warning set: death (OR 1.70, 95%CI 1.02–2.83), mouth cancer (OR 2.09, 95%CI 1.28–3.43), heart disease (OR 1.97, 95%CI 1.26–3.09), wrinkling and aging of skin (OR 1.53, 95%CI 1.03–2.27), stroke (OR 2.02, 95%CI 1.41–2.88), impotence in male smokers (OR 2.92, 95%CI 2.14–3.98), and gangrene (OR 5.27, 95%CI 3.83–7.25).

In Mexico, respondents who viewed the health warning labels specific to the health effect were also more likely to endorse 7 of the 12 health beliefs: throat cancer (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.08–6.83), mouth cancer (OR 2.09, 95%CI 1.19–3.66), heart disease (OR 3.14, 95%CI 1.56–6.32), wrinkling and aging of skin (OR 4.12, 95%CI 2.27–7.43), stroke (OR 3.93, 9%CI 2.61–5.92), impotence in male smokers (OR 3.70, 95%CI 2.37–5.79), and gangrene (OR 4.09, 95%CI 2.75–6.07).

A second set of logistic regression models, which pooled the US and Mexico samples, were conducted for each health effect. Step one of the models included only the ‘Health warnings viewed’ variable. Step two of the models adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender, smoking status, quit intentions, and country. The interaction term between ‘Health warnings viewed’ and country was also tested in this model. Between-country differences were observed for two of the twelve health effects: after viewing health warnings specific to the health effect, respondents in Mexico were more likely than US respondents to endorse the belief that smoking causes wrinkling and aging of the skin (OR 2.72, 95%CI 1.33–5.56) and that smoking causes stroke (OR 1.91, 95%CI 1.10–3.30), compared to respondents in the US. No other significant associations were observed.

Predictors of Health Knowledge

The HBI indicates the number of correct health beliefs (0 to 12) endorsed by respondents. In the US, average HBI score for adults was 8.0 (SD 3.1), significantly lower than the youth mean HBI score of 9.0 (SD 2.6), p<.001. Conversely, in Mexico, mean HBI score was significantly higher for adults compared to youth, at 9.4 (SD 1.8) and 8.8 (SD 1.8), respectively (p<.001).

Linear regression models were conducted, separately by country and age group, to examine the influence of various covariates on level of health knowledge (as measured by the HBI). The youth models included the following covariates: age, gender, and smoking status. The adult models included age, gender, smoking status, quit intentions, education, income, and ethnicity.

Predictors of health knowledge among youth in Mexico and the US

Among youth in Mexico, age emerged as a predictor of health knowledge: older respondents reported higher levels of health knowledge relative to younger respondents (β 0.29, p .001). Non-smokers also reported lower levels of health knowledge than both daily and non-daily smokers (β −0.75, p .001 and β −0.35, p .033, respectively). Among youth in the US, females reported higher levels of health knowledge (β 0.42, p .034). In contrast to Mexican youth, non-smoking youth in the US reported higher levels of health knowledge than both daily and non-daily smokers (β 0.96, p .002 and β 1.40, p < .001, respectively).

Predictors of health knowledge among adults in Mexico and the US

Education was the only significant predictor of health knowledge among adult smokers in Mexico. Those with high levels of education (University degree or higher) reported greater levels of health knowledge compared to those with low (Primary, middle, or technical/vocational school) or moderate (Highschool or some university) levels of education (β 0.63, p .009; β 0.62, p. 001, respectively).

Among adults in the US, age, gender, quit intentions, and income were significant predictors of health knowledge. Older individuals reported lower levels of health knowledge than younger individuals (β −0.03, p <.001). Females reported higher levels of health knowledge than males (β 0.54, p .018). Respondents who were planning to quit were more likely to report higher levels of health knowledge than were those who were not planning to quit (β 1.00, p <.001). Finally, high-income respondents were more likely than both low- and moderate-income respondents to report higher levels of health knowledge (β 1.12, p<.001 and β 0.82, p .003).

DISCUSSION

It is generally assumed that smokers are well aware of the health risks of smoking. Despite widespread endorsement of some more prominent health risks of smoking, such as lung cancer, findings from the current study highlight significant gaps in health knowledge. Most notably, less than half of adult smokers in either country agreed that smoking can cause stroke, one of the leading causes of death from smoking, and only half of US adult smokers agreed that second-hand smoke can cause lung cancer. In addition, less than half of respondents in Mexico and the US believed that smoking causes impotence in male smokers and less than one third believed that smoking causes gangrene.

Mexican respondents reported significantly higher overall levels of health knowledge compared to US respondents. It is noteworthy that the health effects (lung cancer, emphysema, and health risks to unborn babies) with higher levels of endorsement in Mexico were those which appeared on cigarette packages at the time this study was conducted.

The less prominent placement of the text-only US health warnings, coupled with the fact that the same four messages have been in rotation for the last 27 years, may help account for the lower levels of health knowledge found in the US. Pictorial health warning labels were implemented after this study was conducted in Mexico (September 2010) and were scheduled to be implemented in the US in September 2012, pending legal challenges. The new pictorial warnings in Mexico cover 30% of the front and 100% of the back and one side of cigarette packages (www.tobaccolabels.org), and they appear to have increased knowledge about health effects and toxic tobacco constituents addressed in the new warnings (Thrasher, Arillo-Santillán, Pérez-Hernández, Sansores, Regalado-Piñeda, 2011). In the US, the new graphic health warnings will be placed on the top 50% of the front and back of cigarette packages (US FDA, 2011).

Socio-demographic factors were associated with health knowledge in both Mexico and the US. Education emerged as a predictor in the Mexican sample (income was not measured); in the US income, but not education, was associated with health knowledge. Income and education are typically correlated with each other and positively associated with health knowledge. Overall, despite slightly different patterns of socio-demographic predictors in the US and Mexican sample, the current findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the socio-economic gradient in health knowledge.

In the US, youth reported higher levels of health knowledge than adults, whereas the opposite pattern was observed in Mexico. In the US, non-smokers (youth) held higher levels of health knowledge than both daily and nondaily smokers. In contrast, Mexican non-smokers (youth) held lower levels of health knowledge than both daily and non-daily smokers. Previous research in the US and other countries has generally found that non-smokers endorse a greater number of health effects, mostly likely due to higher levels of education among non-smokers and cognitive dissonance among smokers (Hammond et al., 2006). The opposite pattern in Mexico could potentially be a result of its shorter history of tobacco education campaigns, in addition to the warning labels themselves, which smokers were more likely to have seen.

After viewing the relevant health warnings, respondents in both the US and Mexico were more likely to endorse related health beliefs. Increases were greatest for health effects with lower levels of belief, such as gangrene and stroke. These findings are consistent with previous research in which a strong association was found between pictorial health warning labels and health knowledge (O’Hegarty, Pederson, Nelson, Mowery, Gable et al., 2006; Liefeld, 1999).

Limitations

The studies in Mexico and the US were conducted via different survey modes. The face–to-face surveys in Mexico may have encouraged more socially desirable responses among Mexican respondents and may account, in part, for the higher levels of health knowledge, both for targeted and non-targeted health warnings. In addition, the surveys were not conducted with representative samples of smokers, although a heterogeneous cross-section of respondents was recruited in each country.

All respondents in the study viewed two sets of health warnings prior to answering the health knowledge questions. As a result, the levels of health knowledge when respondents viewed non-targeted health warnings are likely to be an over-estimate of health knowledge in the general population given that viewing health warnings for other health effects may increase health beliefs in a non-specific manner. Research conducted after the implementation of pictorial warnings should confirm whether naturalistic exposures to pictorial warnings in each country will produce results that are consistent with those found here. Cross-country research suggests that this will be the case (Hammond et al., 2006; Thrasher, Hammond, Fong, Arillo-Santillán, 2007).

Implications

Overall, the findings suggest that both consumers and the general public are far from fully informed regarding the health effects of tobacco use. Recently, five major tobacco companies have filed a lawsuit against the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) challenging the nine new graphic warning label images to be implemented on cigarette packages in 2012 (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Lorillard Tobacco Company, Common Wealth Brands, Liggett Group, and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company vs. US FDA, 2011). The Motion argues that US smokers and the general public are fully informed of the health risks of smoking and new warnings, therefore, would have no impact. The current study highlights the effectiveness of health warning labels in increasing health knowledge, particularly for less well-known health effects, such as gangrene, impotence in male smokers, and stroke.

Finally, although some differences were observed between the samples in Mexico and the US, the general pattern of the results—including the effect of viewing health warnings—was generally similar across the two countries. These findings add to the evidence base on the potential impact of health warnings.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1 P01 CA138-389-01: “Effectiveness of Tobacco Control Policies in High vs. Low Income Countries”). Additional support was provided by the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award (Hammond), and the CIHR Training Grant in Population Interventions for Chronic Disease Prevention (Mutti).

Contributor Information

SEEMA MUTTI, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

DAVID HAMMOND, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

JESSICA L. REID, Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

JAMES F. THRASHER, Department of Health Promotion, Education and Behavior, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina, USA, and Departamento de Investigaciones sobre Tabaco, Centro de Investigación en Salud Poblacional, Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica (INSP), Cuernavaca, México

References

- Curry SJ, Grothaus L, McBride C. Reasons for quitting: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation in a population-based sample of smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22 (6):727–39. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good BJ, Good MJD. The meaning of symptoms: A cultural hermeneutic model for clinical practice. In: Eisenberg L, Kleanman A, editors. The relevance of social science for medicine. Dordecht, Holland: Reidel; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, McDonald PW, Fong GT, Brown KS, Cameron R. The impact of cigarette warning labels and smoke-free bylaws on smoking cessation: evidence from former smokers. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2004;95(3):201–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03403649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, Borland R, Cummings KM. The effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the ITC 4 country survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Supp 3):iii19–25. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco packages: a review. Tobacco Control. 2011 doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Li Q, Bauer JE, Giovino GA, Steger C, Cummings KM. Predictors of cessation in a cohort of current and former smokers followed over 13 years. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6(suppl3):S363–69. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefeld JP. Prepared for Health Canada. Guelph, Canada: Department of Consumer Studies, University of Guelph; 1999. The Relative Importance of the Size, Content and Pictures on Cigarette Package Warning Messages. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy A, Jezewski M. Cultural variation in the experience of health and illness. In: Albrecht GL, Fitzpatrick R, Scrimshaw SC, editors. The Handbook of Social Studies in Health and Medicine. London: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nourjah P, Wagener DK, Eberhardt M, Horowitz AM. Knowledge of risk factors and risk behaviours related to coronary heart disease among blue and white collar males. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1994;15(4):443–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hegarty M, Pederson LL, Nelson DE, Mowery P, Gable JM, et al. Reactions of young adult smokers to warning labels on cigarette packages. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Lorillard Tobacco Company, Common Wealth Brands, Liggett Group, and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company v. United States Food and Drug Administration, Margaret Hamburg, Commissioner of the United States Food and Drug Administration, and Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Case 1:11-cv-01482-RJL. Filed 08/19/2011.

- Romer D, Jamieson P. The role of perceived risk in starting and stopping smoking. In: Slovic, editor. Smoking: risk, perception, and policy. Thousand Oaks California: Sage; 2001. pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sudman S. Improving the Quality of Shopping Center Sampling. Journal of Marketing Research. 1980;17 (4):423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Hammond D, Fong G, Arillo-Santillán E. Smokers’ reactions to cigarette package warnings with graphic imagery and with only text: A comparison of Mexico and Canada. Salud Pública de México. 2007;49(SuppI):S233–240. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342007000800013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillán E, Pérez-Hernández R, Sansores R, Regalado-Piñeda J. Cigarette package warning labels: Four studies of impact and recommendations for the second round of pictorial warning labels in Mexico. Secretaría de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; México: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. [accessed July 24 2011];Required warnings for cigarette packages and advertisements; Final rule. 2011 Jun; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/CigaretteWarningLabels/ucm259214.htm. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic: the MPOWER package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008b. [Google Scholar]