Abstract

In adult mammals, the production of insulin and other peptide hormones, such as the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), is limited to β-cells due to tissue-specific expression of a set of transcription factors, the best known of which is Pdx1. Like many homeodomain transcription factors, Pdx1 binds to a core DNA recognition sequence containing the tetranucleotide 5´-TAAT-3´; its consensus recognition element is 5´-CTCTAAT(T/G)AG-3´. Currently, a complete thermodynamic profile of Pdx1 binding to near-consensus and native promoter sequences has not been established, obscuring the mechanism of target site selection by this critical transcription factor. Strikingly, while Pdx1 responsive elements in the human insulin promoter conform to the pentanucleotide 5´-CTAAT-3´ sequence, the Pdx1 responsive elements in the human iapp promoter all contain a substitution to 5-TTAAT-3´. The crystal structure of Pdx1 bound to the consensus nucleotide sequence does not explain how Pdx1 identifies this natural variation, if it does at all. Here we report a combination of isothermal calorimetric titrations, NMR spectroscopy, and extensive multi-microsecond molecular dynamics calculations of Pdx1 that define its interactions with a panel of natural promoter elements and consensus-derived sequences. Our results show a small preference of Pdx1 for a Cyt base 5´ relative to the core TAAT promoter element. Molecular mechanics calculations, corroborated by experimental NMR data, lead to a rational explanation for sequence discrimination at this position. Taken together, our results suggest a molecular mechanism for differential Pdx1 affinity to elements from the insulin and iapp promoter sequences.

Keywords: homeodomain, A-box element, diabetes, isothermal titration calorimetry, nuclear magnetic resonance

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a complex metabolic disease characterized by persistent hyperglycaemia resulting from either insufficient quantities of insulin, deficient insulin response in peripheral tissue, or both. In adult mammals, insulin production is limited to β-cells due to restricted expression of a set of tissue-specific transcription factors.1 While the primary endocrine function of the β-cells is insulin secretion in response to increases in blood glucose levels, these crucial cells also release small amounts of other peptide hormones, including the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP, or amylin),2,3 which is present in β -cell secretory granules at approximately one-third the molar concentration of insulin.3 Due to their co-storage in β-cell secretory granules, the concentrations of insulin and IAPP in the blood change in parallel in response to glucose stimulation,4 supporting the hypothesis that IAPP is involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism.5 Importantly, the level of IAPP produced must be tightly controlled, because an excess of this hormone has been shown to inhibit glucose-induced insulin secretion.6 IAPP is a regulatory peptide that functions in energy homeostasis, primarily by signaling satiation.7 Binding of IAPP in the brain inhibits gastric emptying and elicits an anorectic response, resulting in reduced food intake.8,9 Gastric emptying is pathologically rapid in type 1 diabetes, suggesting a phenotypic role for the absence of IAPP in this form of the disease.10 Strikingly, both the iapp and insulin genes contain many similar promoter elements that regulate the effects of glucose on their transcription.11,12

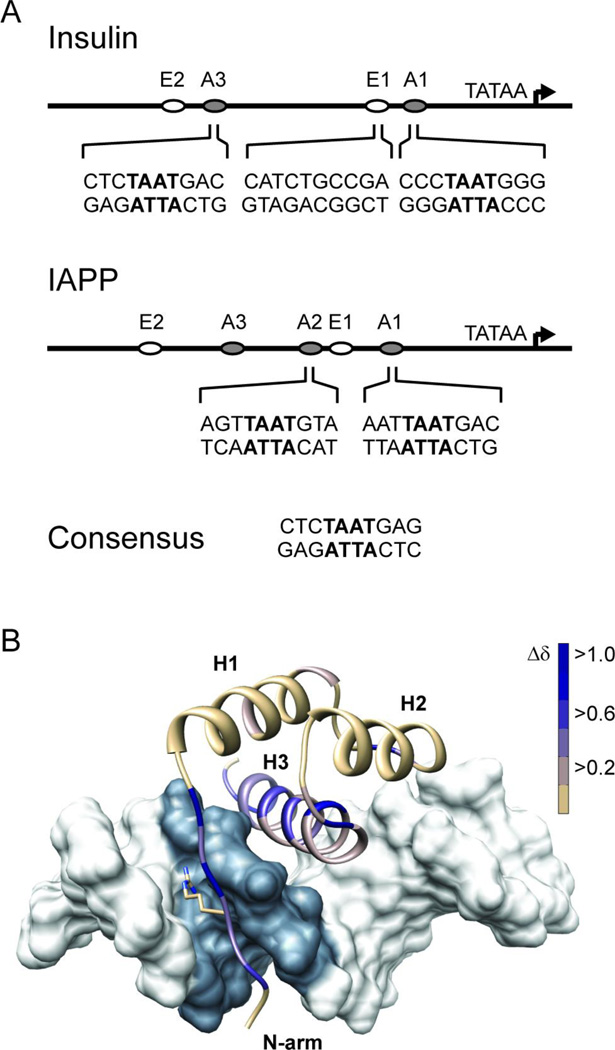

While no single protein or multi-protein complex alone accounts for cell-specific insulin or IAPP expression, the pancreatic duodenal homeobox protein 1 (Pdx1; also known as Iuf1, Ipf1, Idx1, Stf1, and Gsf) fulfills a central role in pancreatic development, endocrine pancreas maintenance, and activation of the insulin and iapp genes.13–17 Further, it is known that the Pdx1 DNA-binding activity directly induces both insulin and IAPP production in response to glucose.17–19 The consensus Pdx1 binding site has previously been reported as 5´-CTCTAAT(T/G)AG-3´.20,21 Natural sequences similar to this consensus are found in both the insulin and iapp gene promoters (Figure 1). Variation in the TAAT “core” recognition element, which is a required motif bound by most homeobox transcription factors, is poorly tolerated; variation in the peripheral positions of this core sequence has been documented to produce tenfold increases in measured in vitro Pdx1 dissociation constants (Kd) that manifest as substantial reductions in promoter activity in vivo.21 Once recruited to a promoter through its homeodomain, Pdx1 also interacts with multiple additional regulatory proteins, allowing synergistic interactions and modification of transcription outcomes in response to the current environment.22

Figure 1.

Pdx1 recognizes A-box motifs common to the insulin and iapp gene promoters. (A) Schematic representations of the insulin and iapp gene promoters depict the relative location of A-box promoter elements, and the adjacent E-box elements, which are also involved in regulating transcription from these promoters. The nucleotide sequence in the neighborhood of the core TAAT element (denoted in bold) is shown for each of the four A-boxes investigated in this study. Pdx1 does not bind to E-boxes and so the insulin E1 sequence is used as a control for non-specific DNA binding in this study. (B) The DNA binding epitope of Pdx1 is confirmed by monitoring changes in the backbone amide chemical shift between the unbound and consensus-DNA bound states. Chemical shift changes (Δδ) are mapped as progression from tan to blue onto a ribbon-representation of Pdx1 in complex with duplex-DNA (molecular surface of pdb 2h1k, in which the core TAAT element is depicted in grey). Δδ represents the weighted change in amide 1H and 15N chemical shift for each residue and is calculated using Equation 1 (see Methods). Pdx1 secondary structural elements are labeled as H1 – H3 (α-helix-1,2,3 respectively) and the N-terminal arm is also labeled for reference. Also depicted is the side chain of Arg-150, which is shown in the crystallographic orientation.

Given that Pdx1 is crucial for the expression of genes central to the mature β-cell phenotype, it is surprising that many of the details of the molecular mechanism for Pdx1 influence on gene expression remain to be defined.23 In this regard, the recently published crystal structure of Syrian hamster Pdx1 bound to a DNA duplex containing the consensus Pdx1 binding site provided a major breakthrough, by suggesting the atomic origins for much of the sequence specificity imparted by elements flanking the TAAT core.24 To briefly summarize, Longo et al.24 report that all three nucleobases in the strand opposite the consensus GAG sequence (found on the 3´-side relative to the TAAT motif) are directly contacted by residues Gln-195 and Met-199 of the homeodomain.a Further, Longo et al. suggest that the C·G base pair immediately 5´ to the TAAT must be recognized by the side chain of Arg-150, which is found in the intrinsically disordered N-terminal arm of the homeodomain (see Figure 1). This assertion was made despite an absence of direct contacts between Arg-150 and either nucleobase of the C·G pair in the deposited structure model.24 Strikingly, the Pdx1 responsive elements in the promoter of the human iapp gene all contain a substitution from 5-CTAAT-3´ to 5-TTAAT-3´, underscoring the need to more fully understand nucleotide specificity in this position.

Currently, there is no rigorous molecular mechanism defining and rationalizing variation in Pdx1 affinity for DNA sequences similar to the consensus motif, beyond the preliminary information provided by elucidation of the Pdx1-homeodomain structure in complex with consensus DNA.24 Thus, a systematic study of interactions involving non-consensus DNA sequences is needed to provide a rationale for understanding differential affinity of Pdx1 to disparate promoters that it regulates. Importantly, while the insulin promoter and the factors that bind it are well studied, far less effort has been put into fully characterizing the regulation of promoters for other proteins with significant roles in maintaining β-cell function, including the iapp promoter.13 Functional assays illustrating differential Pdx1 stimulated transcription levels have been reported that anecdotally correlate with differences in AT-rich sequence,19,25 but the results have not been directly verified through in vitro biophysical methods.

The present study aims to provide a molecularly detailed characterization of the differences between Pdx1 binding to regulated promoter elements from the insulin and iapp genes. Here we report the thermodynamics of Pdx1 binding to both consensus and human promoter derived DNA sequences, assayed by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Our results show a preference of Pdx1 for a Cyt in the 5´-position with respect to the core TAAT promoter element. Additionally, we report NMR spin relaxation measurements and extensive multi-microsecond molecular dynamics calculations of Pdx1, both in the unbound state and bound to consensus DNA, which lead to a mechanistic hypothesis for the origins of sequence discrimination 5´ to the TAAT element. Our results rationalize the role of the intrinsically disordered N-terminal arm of Pdx1 in providing differential affinity for sites from the insulin and iapp gene promoters.

Results and Discussion

NMR verification of the solution binding interface

The crystal structure of Syrian hamster Pdx1 bound to a DNA duplex containing the consensus Pdx1 binding site adopts the canonical homeodomain fold, with three segments of α-helix and an extended N-terminal tail that inserts into the minor groove of the DNA.24 The crystal structure of Pdx1 homeodomain in complex with a consensus DNA sequence (referred to here as DNACON) revealed that Pdx1 adopts the canonical homeodomain binding mode, with helix-3 inserting into the major groove of the DNA duplex and the intrinsically disordered N-terminal arm of the domain, which bears the strongly conserved residue Arg-150, bound to the minor groove (Figure 1B). We have verified that the co-crystal structure accurately represents the solution-state of the Pdx1-DNACON complex by solution NMR spectroscopy. Standard double and triple resonance spectra of apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex were acquired on an 850 MHz spectrometer, yielding complete backbone assignments of both states (although we note that in apo-Pdx1 Tyr-153 is the closest residue to the N-terminus yielding quantitative results at our experimental pH, due to rapid solvent exchange in this highly exposed region). DNA binding by Pdx1 resulted in a specific and temporally stable complex, as evidenced by the sharp 2D-lineshapes in the 1H,15N-HSQC of the complex and by the change in peak distribution relative to the unbound state (Supplemental Information, Figure S1). These results are in agreement with the DNA-bound crystal structure of Pdx1 and with our ITC results (vide infra). Chemical shift perturbations are mapped onto the structure of Pdx1, represented as the complex with dsDNA in Figure 1B. Almost all residues displaying large changes in backbone amide proton and nitrogen chemical shifts interact with the core TAAT sequence element of the DNA (shaded dark grey in Figure 1B), or are adjacent to those interaction sites, and are located in helix-3 or the N-terminal arm. A quantitative representation of per-residue chemical shift changes is presented in the Supplemental Information, Figure S1.

Thermodynamic analysis of promoter-derived DNA binding by Pdx1

Pdx1 binds to multiple sites within the promoters of β-cell specific genes, including insulin and iapp, where the bound DNA elements show sequence variation at positions believed to be recognized with nucleotide-specificity by Pdx1. Thus, characterization of binding to an idealized consensus sequence alone is not sufficient to describe the biological role of this factor well; it is important to characterize the thermodynamics of Pdx1 interactions with a set of related DNA sequences derived from natural promoter elements, as well as its interaction with sequences perturbed by point mutation.

Sequences similar to the consensus 5´-CTCTAAT(T/G)AG-3´ recognition element, generally referred to as A-boxes, are commonly found in multiple copies throughout the proximal promoter regions of β-cell associated genes. For example, A-boxes are found within the −400 to +1 region of the insulin and iapp gene promoters,12,26 the relative positions and exact sequences of which are provided in Figure 1. Multiple groups have reported equilibrium dissociation constants for Pdx1 binding to the A1 and A3 boxes from the rat and mouse insulin promoters, finding through competition gel mobility shift assays that the affinity is typically on the order of 1–5 nM.21,24,27,28 In contrast, affinities of Pdx1 for neighboring E-box elements, lacking the core TAAT element, have been reported to range from 20–150 nM by similar assays,21,24 suggesting that the in vitro specificity of Pdx1 for the A-box is not dramatic.

Significantly, the A-box elements of the insulin and iapp gene promoters diverge at the 5´-position relative to the core TAAT recognition element (Figure 1), nderscoring the importance of determining whether Pdx1 is sensitive to the nucleotide identity of this region. The co-crystal structure of Pdx1 bound to consensus DNA offers little guidance on this key issue. The crystallographic orientation of the side chain of Arg-150 facilitates engagement in hydrogen bonding with the Thy base of the 5´-base pair of the TAAT element exclusively; neither Arg-150 nor any other Pdx1 residue is in direct contact with the C·G base pair to the 5´-side of the core TAAT element. Here we have performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments at 298K to measure the interaction of Pdx1 with a total of 16 DNA sequences derived both from natural human promoter elements (Table 1) and from systematic point-mutation of the consensus sequence (Table 2). For each interaction, fitting parameters proportional to the binding enthalpy (ΔH), binding affinity (as reported by the equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd), and stoichiometry of interaction (n) are reported. The determined parameters reveal patterns in nucleotide sequence recognition that rationalize previously estimated levels of in vivo gene activation by Pdx1.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters describing binding of Pdx1-HD to dsDNA derived from natural human promoter elements; measured at 298K in 100 mM cacodylate, pH 7.3, 100 mM KCl. The core TAAT recognition element is shown in bold (except in the E1 element, which lacks it, and is used in this study as a control to describe non-specific binding). All error bars on fitted ITC parameters represent standard error of the mean estimated from triplicate measurements, with fitting performed in Origin 7.0 (MicroCal, Inc.).

| DNA | Forward Sequence | n | Kd (nM) | ΔH (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin A1 | 5´-AGGCCCTAATGGGCCA-3´ | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 7 ± 2 | −10.2 ± 0.1 |

| Insulin A3 | 5´-AGACTCTAATGACCCG-3´ | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 4 ± 1 | −9.63 ± 0.05 |

| Insulin E1 | 5´-AGCCATCTGCCGACCC-3´ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1300 ± 300 | −2.7 ± 0.1 |

| IAPP A1 | 5´-GGAAATTAATGACAGA-3´ | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 5 | −4.60 ± 0.03 |

| IAPP A2 | 5´-ATGAGTTAATGTAATA-3´ | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 27 ± 7 | −5.71 ± 0.05 |

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters describing binding of Pdx1-HD to dsDNA derived from the consensus binding sequence; measured at 298K in 100 mM cacodylate, pH 7.3, 100 mM KCl. The core TAAT recognition element is shown in bold and mutations are highlighted in italics. All error bars on fitted ITC parameters represent standard error of the mean estimated from triplicate measurements, with fitting performed in Origin 7.0 (MicroCal, Inc.).

| DNA | Forward Sequence | n | Kd (nM) | ΔH (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus | 5´-CCACTCTAATGAGTTC-3´ | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 5 ± 1 | −8.58 ± 0.04 |

| Con. T1→A | 5´- CCACTCAAATGAGTTC -3´ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 20 ± 4 | −4.98 ± 0.03 |

| Con. A2→T | 5´- CCACTCTTATGAGTTC -3´ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 360 ± 50 | −3.88 ± 0.04 |

| Con. A3→T | 5´- CCACTCTATTGAGTTC -3´ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 110 ± 20 | −2.74 ± 0.03 |

| Con. T4→A | 5´- CCACTCTAAAGAGTTC -3´ | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 64 ± 4 | −6.27 ± 0.02 |

| Con. 5´C→G | 5´- CCACTGTAATGAGTTC -3´ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10 ± 2 | −7.45 ± 0.03 |

| Con. 5´C→A | 5´- CCACTATAATGAGTTC -3´ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 9 ± 1 | −7.07 ± 0.02 |

| Con. 5´C→T | 5´- CCACTTTAATGAGTTC -3´ | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 8 ± 1 | −7.00 ± 0.02 |

| Con. 3´G→A | 5´- CCACTCTAATAAGTTC -3´ | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 11 ± 3 | −4.29 ± 0.02 |

| Con. 3´G→T | 5´- CCACTCTAATTAGTTC -3´ | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4 ± 1 | −8.86 ± 0.03 |

| Con. 3´G→C | 5´- CCACTCTAATCAGTTC -3´ | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 30 ± 3 | −9.08 ± 0.02 |

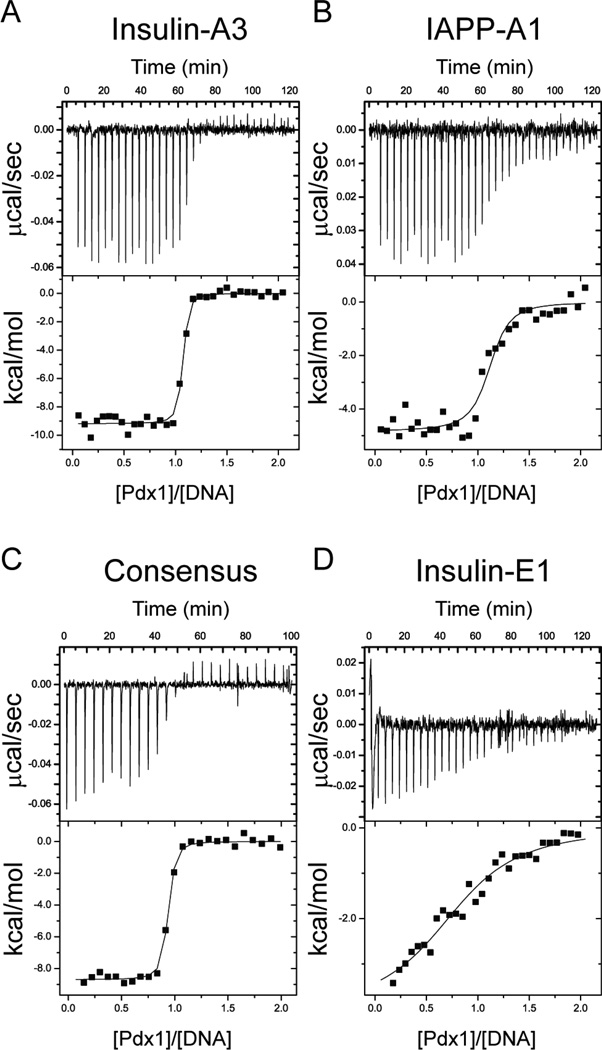

The overall trends in our data set are summarized by the representative titrations presented in Figure 2 for Pdx1 binding to Insulin-A3, IAPP-A1, the DNACOn sequence, and Insulin-E1. A comprehensive list of best fit parameters for the set of titrations involving natural promoter sequences is provided in Table 1. Among the natural A-box sequences investigated here, Insulin-A3 and IAPP-A1 bear the most sequence identity to one another and with respect to the consensus high-affinity sequence: although their 5´-sequences diverge, both elements contain the required TAAT core and are identical through the first three base pairs on the 3´-side of the core element; the first two of these shared 3´-nucleotides are also identical in sequence to the consensus. Insulin-A3 and DNACON are nearly identical in the Pdx1 binding region, making it unsurprising that the measured dissociation constants for Pdx1 binding to both were indistinguishable within experimental uncertainty. In contrast, we find an approximate five-fold lower affinity of Pdx1 for IAPP-A1 than for Insulin-A3, or for DNACON, suggesting that one or more nucleotides on the 5´-side of the core TAAT element contribute significantly to sequence recognition by Pdx1. This result generalizes in that both insulin derived A-boxes studied contain the core pentanucleotide 5´-CTAAT-3´ sequence and were found to bind with affinities indistinguishable within error from that of the consensus element, whereas both iapp derived A-boxes contain a deviating 5´-TTAAT-3´ pentanucleotide and display affinities that are approximately five-fold weaker than Pdx1 binding to DNACON.

Figure 2.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) monitors the thermodynamics of Pdx1 interactions with natural and consensus DNA promoter elements. Representative power-response curves (top) and heats of reaction normalized to the moles of Pdx1 injected (bottom) are provided for the titration of Pdx1 into (A) Insulin-A3 DNA, (B) IAPP-A1 DNA, (C) Consensus DNA, and (D) Insulin-E1 DNA. All titrations were conducted at 298K in 100 mM cacodylate, pH 7.3, and 100 mM potassium chloride.

As a control defining the strength of non-specific double-stranded DNA interactions, we tested Pdx1 binding to the Insulin-E1 element, which lacks the TAAT sequence generally required for sequence-specific binding by homeodomains. As expected, the Insulin-E1 binds poorly, with an approximate 250-fold loss of affinity relative to DNACON under our experimental conditions. Thus, we observe that Pdx1 has a modest preference for insulin-derived promoter elements over those derived from the iapp gene, but that both are bound selectively over nonspecific background DNA.

Mutational analysis using modified DNACON ligands

As shown in Table 1, the A-box elements of the insulin and iapp promoters differ mainly at the 5´-position relative to the core TAAT recognition element and the affinity of Pdx1 for each of these two sub-sets of A-box sequences is systematically different. Therefore, we sought to quantify Pdx1’s ability to discriminate nucleotide sequence at this position by conducting calorimetric titrations in which we systematically varied its nucleotide identity. For these studies, we used DNA oligonucleotides derived from the consensus sequence as 5´-CCACTNTAATGAGTTC-3´, where N is either C (wild-type), G, A, or T. The results suggest that Pdx1 has a slight preference for Cyt at the 5´-position (as summarized in Table 2). Although the observed effect was modest (only a 2-fold change in affinity), this substitution accounts for nearly half of the 5-fold average difference observed between equilibrium binding constants for insulin and iapp derived A-box sequences (Table 1). Additionally, these promoters contain multiple A-boxes, often adjacent to E-boxes, as shown in Figure 1. Thus, we emphasize that heterotropic linkage effects involving interactions with additional binding partners recruited to the promoter by Pdx1 (and also homotropic effects involving multiple copies of Pdx1 binding to the multiple A-boxes) could readily amplify the impact of Cyt-to-Thy substitution in this position of the iapp promoter, relative to the insulin promoter sequence.

In addition to determining the binding affinity in a label-free assay, ITC provides direct determination of binding enthalpies, which can provide insight into the molecular mechanisms of interactions. Pdx1 binding to Cyt in the 5´-position is enthalpically more favorable than Gua, Ade, or Thy in this position (Table 2), which is consistent with the systematic difference in binding enthalpy of insulin versus iapp derived sequences (Table 1) and with the differential electrostatic stabilization of Arg-150 in the minor groove observed in molecular dynamics simulations of Pdx1 in complex with each of these four sequences (vide infra).

The significance of the Cyt-to-Thy substitution discussed above has the potential to impact relative recruitment of Pdx1 to the insulin and iapp promoters and underscores the need to explore Pdx1 sequence preferences rigorously. Further motivating our research, a systematic study of the engrailed homeodomain by Ade et al. demonstrated the effects of modifying bases in the core and flanking regions of its preferred binding sequence, revealing regions where mutation decreased the binding affinity and modified functional outcomes.29 Therefore, we continued our study with Pdx1 titrations against variants of the DNACON sequence intended to disrupt the TAAT motif (summarized in Table 2).

In the co-crystal structure of Pdx1 bound to DNA, the first and fourth bases in the TAAT core sequence are only contacted by a single residue. Moreover, the only direct contact to the fourth base pair is a van der Waals interaction in the minor groove mediated by Ile-192, which led Longo et al. to speculate that Pdx1 may be tolerant of DNA mutations in this position.24 Through ITC, we observe that when the Thy bases at position 1 and 4 are inverted to Ade, the Pdx1 binding affinity weakens by 4- and 12-fold, respectively. Interestingly, inverting the base pair at position 1 of the TAAT element results in a binding enthalpy close to that of the iapp promoter-derived sequences and much smaller in magnitude than those observed for the insulin promoter-derived and wild-type consensus sequence. Moving into the interior of the TAAT core site, the crystal structure reveals that significantly more residues in helix-3 and in the disordered N-terminal arm contact the bases in positions 2 and 3. Unsurprisingly, a more pronounced effect on the Kd is observed when positions 2 and 3 are inverted from Ade to Thy, weakening the affinity by approximately 75-fold and 20-fold, respectively.

To complete our mutational analysis, we systematically varied the nucleotide identity at the 3´-position relative to the TAAT element, because prior reports suggest that Pdx1 exhibits sequence bias for Gua or Thy at this location.20,21 The Pdx1-DNA co-crystal structure demonstrates that Met-200 makes hydrophobic contacts with the Cyt base of the 3´ G·C base pair on the strand opposing the TAAT element. Similar interactions would be possible with an Ade base in a T·A base pair, suggesting a mechanism for the Gua/Thy preference predicted at the 3´-position. Our ITC results corroborate these findings, showing a 2- to 6-fold enhancement in affinity for Gua or Thy in the 3´-position, as compared to the binding affinity observed for Ade or Cyt in this position (Table 2).

In summary, we find that the TAAT element is indispensible for sequence-specific Pdx1 binding, as predicted by the many interactions between Pdx1 helix-3 and the DNA nucleobases in the co-crystal structure. Additionally, nucleobase-specific interactions in the 5´- and 3´-flanking sequences predicted from establishment of the 5´-CTAAT(T/G) -3´ consensus are confirmed by our studies, although we find that the quantitative contributions from the 5´ C·G and 3´ T·A or G·C base pair are small in magnitude. Significantly, discrimination between a 5´ C·G base pair, seen in human insulin promoter sequences, and a 5´ T·A base pair, seen in human iapp promoter sequences, is established. As with many homeodomains that recognize nucleotide identity in the region proximal to the 5´-side of the TAAT motif, recognition of the 5´-pair by Pdx1 appears from the crystal structure to be mediated through the minor groove of the duplex DNA, where there is a paucity of chemical information capable of defining nucleotide sequence, as compared to what would be made available through major groove interactions. Therefore, the remainder of the work presented here will aim to provide a mechanistic explanation for the thermodynamic preferences we have quantified by ITC with respect to nucleotide composition on the 5´-side of the TAAT motif.

Long timescale molecular dynamics simulations

Placing the thermodynamic data presented above in the context of the co-crystal structure of Pdx1 bound to a consensus derived DNA duplex suggests that penetration of the Arg-150 side chain into the minor groove is responsible for imparting 5´ nucleotide specificity (Figure 1). While the crystallographic orientation of Arg-150 explains its contribution to recognizing the first position of the core TAAT element, it provides no clear evidence for how Arg-150 may mediate sequence discrimination at the 5´-position relative to TAAT, because no nucleobase-specific contacts are made to this base pair.24 In all likelihood, the crystallographic conformation of Arg-150 reflects one of many thermally accessible conformations. Therefore, experiments designed to enumerate more fully the conformational states accessible to this key residue – as well as those of the remainder of the N-terminal arm and homeodomain – could provide insight into the mechanism of sequence discrimination imparted by the N-terminal arm.

Most experimental methods, such as the NMR spin relaxation studies also reported here, provide a temporally averaged description of the dynamics in biomolecular systems. Therefore, computational approaches that enable time-resolved sampling of conformational ensembles reflect an important complement to experimental studies. Recent advances in both computing power and force field quality have made computer simulation of dynamic regions like the Pdx1 N-terminal arm on meaningful timescales feasible.30,31 Therefore, we chose to calculate molecular dynamics trajectories of Pdx1, starting from the co-crystal structure, based on the hypothesis that thermally accessible fluctuations away from the crystallized conformation of the tail would elucidate the atomic-scale interactions responsible for our observed binding thermodynamics. In order to assure sufficient sampling to test our hypothesis, we have conducted our simulations using the Anton machine, which was purpose-built to enable long-timescale molecular mechanics calculations for biomolecular systems.32 We have calculated 5 µs simulations for Pdx1-DNA complexes including each of the four 5´-position variants used in our ITC studies, as well as a 5 µs simulation of apo-Pdx1, resulting in 25 µs of total sampling. The results, which we validate through comparison with experimental NMR data, provide a reasonable atomic-scale mechanism for nucleobase-sequence identification at the 5´-position, relative to the TAAT core, by Arg-150.

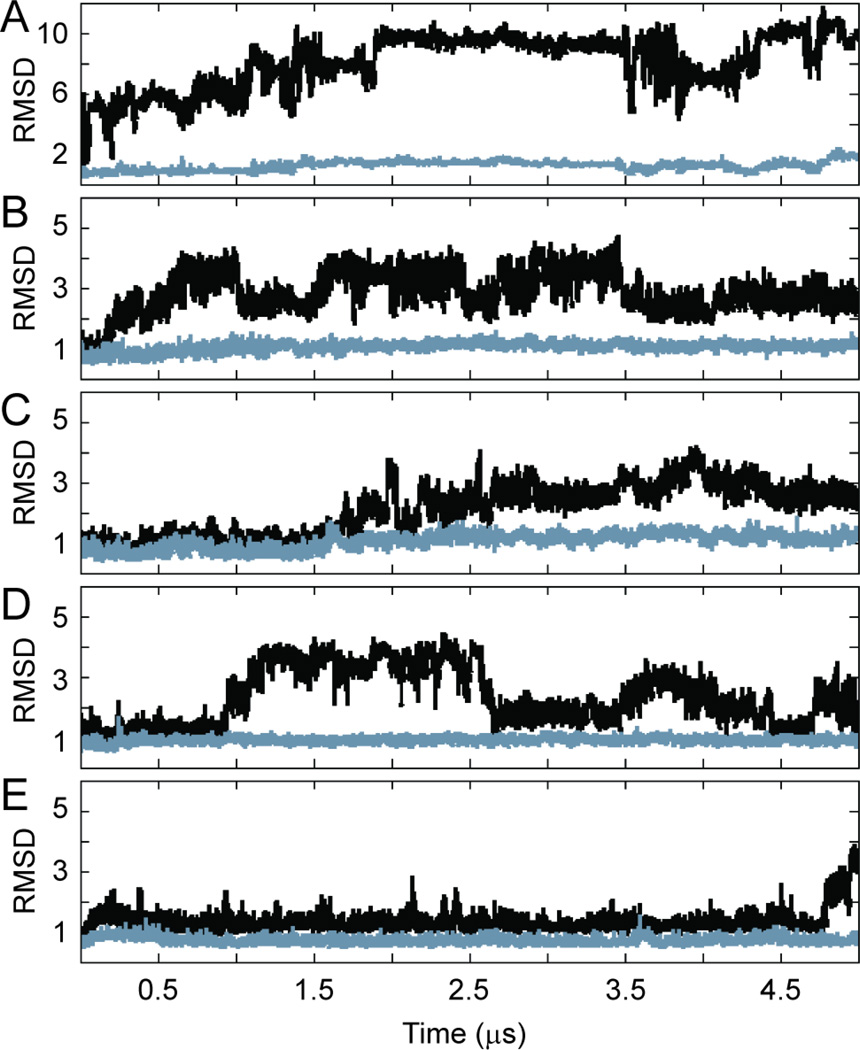

The stability of the homeodomain and homeodomain-DNA complex during our 5 µs Anton simulations is shown by the root mean squared deviation from the starting conformation, displayed as a function of time in Figure 3. Both apo-Pdx1 (Figure 3A) and the Pdx1-DNA complex (Figure 3B; mutants in panels C-E) were found to be remarkably stable overall on this extended timescale, with the C-terminal end of helix-3 being a major exception to that trend. There is precedent to support this result, as the NMR solution structure of the homeodomain Antp-DNA complex (pdb 1ahd) displays significant disorder in the same region of helix-3.33 Still, we were concerned that the unraveling of helix-3 in our simulations may have been an artifact, and so we sought to quantify the extent of helicity in the same region of apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex experimentally.

Figure 3.

Pdx1 root-mean-squared deviation (RMSD) from the crystal structure during the five-microsecond production molecular dynamics calculations performed on Anton. Results are shown for (A) apo-Pdx1, (B) Pdx1-DNACON(CTAATG), (C) Pdx1-DNA(ATAATG), (D) Pdx1-DNA(GTAATG), and (E) Pdx1-DNA(TTAATG). For each trajectory, the Pdx1 RMSD (Å) is shown for all backbone heavy atoms (black) and for the backbone heavy atoms of residues 155–199 only (grey). Data points are reported once per 200 ps of simulaton time.

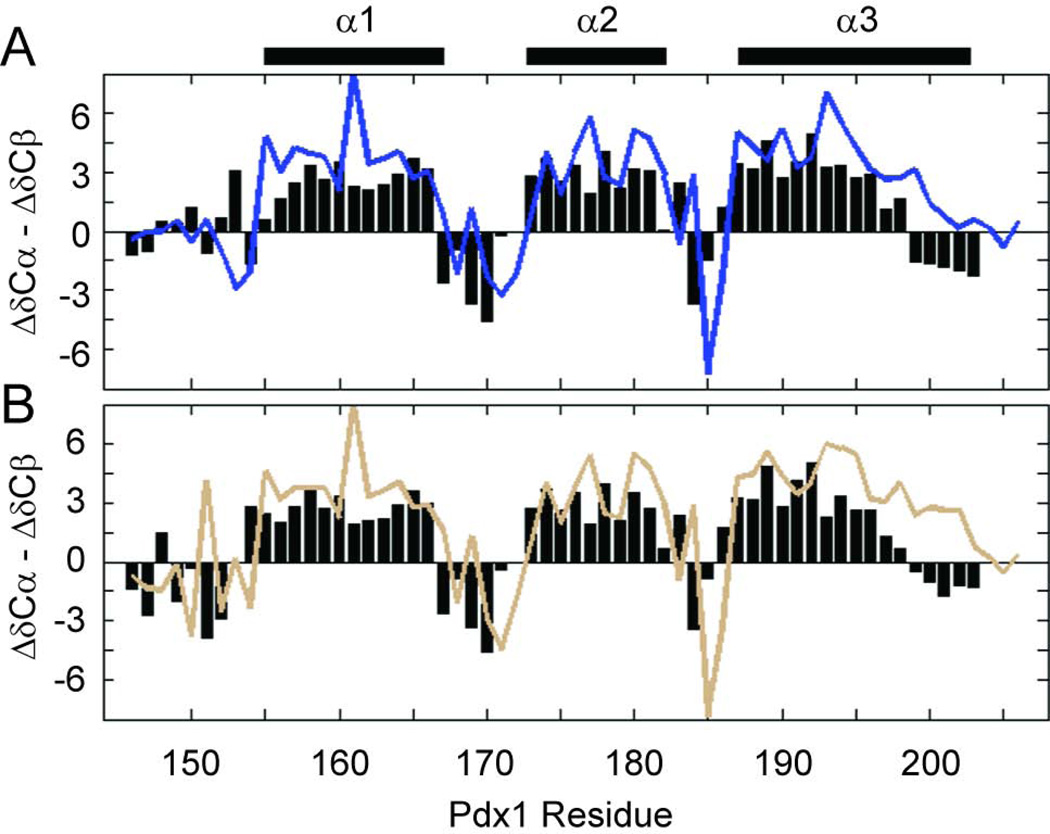

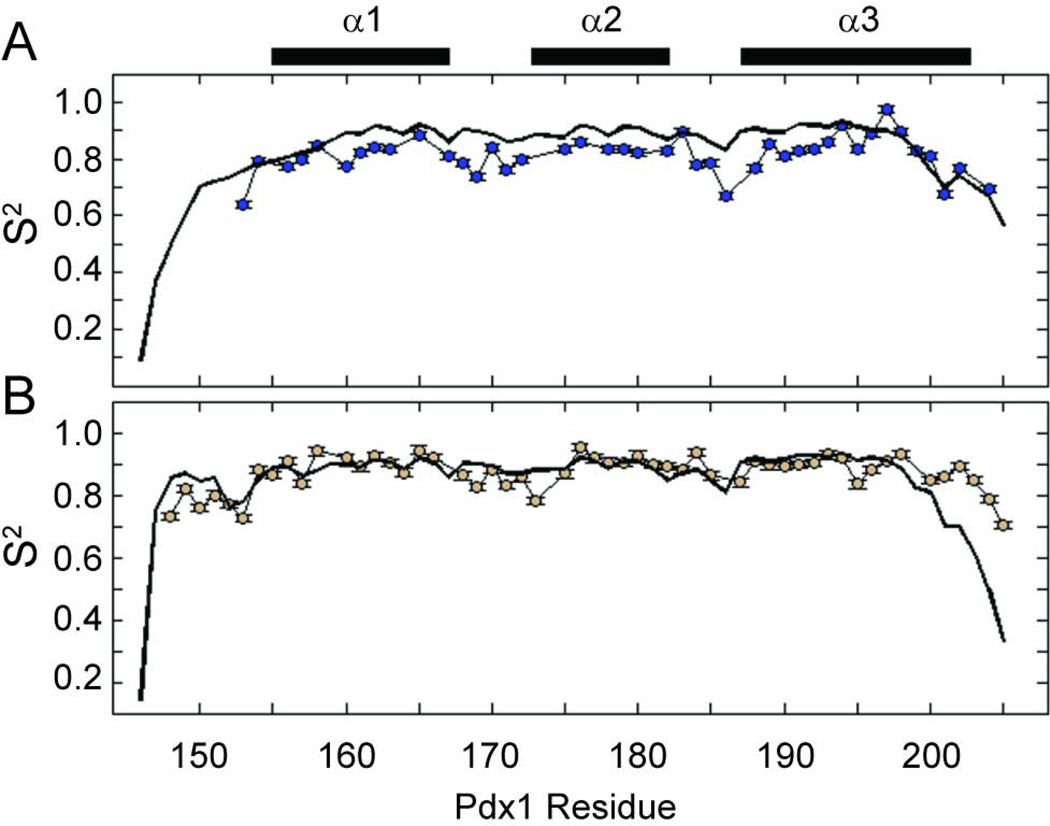

Backbone NMR chemical shifts are a robust indicator of polypeptide secondary structure and are therefore the ideal metric to assess similarity in the average helicity of helix-3 in our simulations and in vitro. As summarized in Figure 1B, we have acquired NMR chemical shifts for the backbone of both apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex (deposited in the BMRB with ID numbers 19227 and 19228, respectively). Secondary structure propensity (SSP) is widely used method for utilizing chemical shifts to predict the structure of proteins; α-helix and β-strand structures, as opposed to random coil structures, are predicted based on positive or negative SSP values, respectively. Notably, values greater than or equal to 2 in absolute magnitude signal stable secondary structure.34 Importantly, the N-terminal arm of Pdx1 is shown by SSP analysis to be disordered in apo-Pdx1 for those residues having assignments (Figure 4A), as expected. Apo-Pdx1 also displays three clear regions of α-helical structure, but the boundaries of these structures are only consistent with the co-crystal structure for helix-1 and helix-2; the C-terminus of helix-3 shows significant fraying in the SSP data, which is qualitatively consistent with the predictions from our MD simulations.

Figure 4.

Secondary 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts indicate the boundaries of secondary structure in (A) apo-Pdx1 and (B) the Pdx1-DNACON complex. Plotting the difference between 13Cα and 13Cβ secondary chemical shifts indicates the presence of an α-helix when long stretches of positive values are encountered. The secondary structure from the co-crystal of Pdx1 with a consensus DNA duplex is represented by bars above the figure for comparison. In both panels, the experimental secondary shift difference is reported by a colored line, whereas the predicted values resulting from the Anton MD trajectories is represented by black bars.

Similarly to the data for apo-Pdx1, the experimental chemical shifts from the Pdx1-DNACON complex yield SSP values that indicate a consistent overall structure for the homeodomain in vitro and in our MD simulations. First, while the N-terminal arm is ordered in the complex, assignment of regular α-helical or β-strand structure is not merited by SSP (Figure 4B). Second, assignment of all three α-helices is similar between the experimental and MD chemical shifts, although fraying of helix-3 is more pronounced in the MD simulation than in our in vitro experiments. This result is consistent with what we also observed for apo-Pdx1. Taken together, the chemical shift analysis suggests that the average conformations of apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNAcon complex in our MD simulations are representative of the solution averages. The existence of fraying in the C-terminus of helix-3 and the known dynamic state of the N-terminal arm suggest that additional analysis of the fluctuations about these average structures will also yield insight into the structural ensembles and DNA-binding mechanism of Pdx1.

Backbone dynamics of Pdx1 in the apo- and DNA-bound states

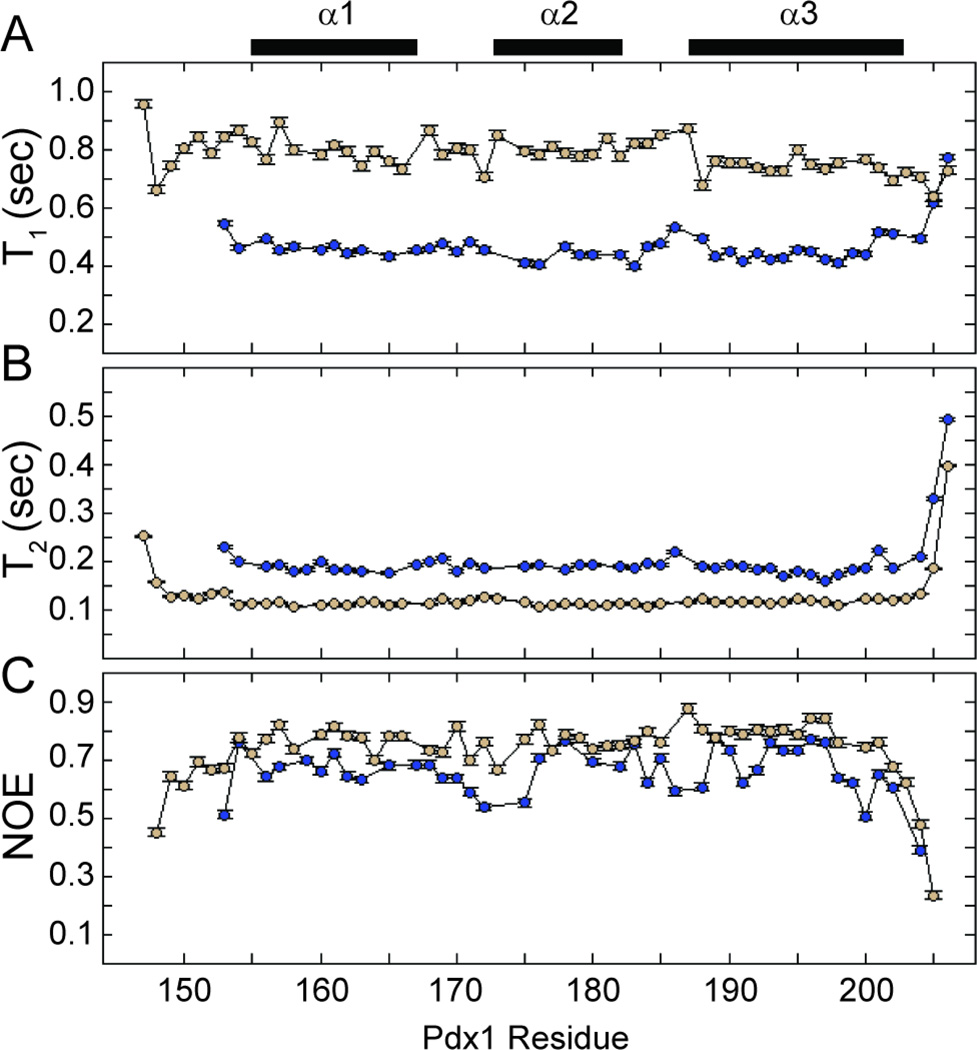

If the overall folding features we observed in our Anton trajectories are reasonable, then the enhanced disorder in the N-terminal arm and the C-terminus of helix-3 should manifest in larger amplitude fluctuations of the backbone conformation in these regions, relative to the temporally stable portions of the protein found in the folded core of the homeodomain. In particular, enhanced dynamics on the ps-ns timescale should be observed for the disordered N-terminal tail and the frayed end of helix-3. Such dynamics are measurable through NMR spin relaxation methods.35,36 Importantly, these dynamics can also be accessed through analysis of the fluctuations recorded in our MD simulations,37 allowing additional cross-validation of the experimental and computational data sets. Therefore, we have collected 15N-NMR spin relaxation measurements on a 500 MHz spectrometer for apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex, which are summarized in Figure 5. The raw data indicate a picture that is consistent with the chemical shift analysis reported above, where the N-terminal arm of Pdx1 appears to be relatively static in the complex and the C-terminus of helix-3 appears to be more dynamic in the apo-state.

Figure 5.

Backbone 15N-T1, T2, and 1H,15N-NOE measured on a 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. (A) 15N-T1, (B) 15N-T2, and (C) 1H,15N-NOE are reported for apo-Pdx1 (blue) and the Pdx1-DNAcon complex (tan). Experimental uncertainties in the measured parameters are indicated as error bars, which often do not exceed the size of the markers on the plot. The secondary structure from the co-crystal of Pdx1 with a consensus DNA duplex is represented by bars above the figure.

In order to better quantify the dynamics we observed, we performed modelfree analysis38 of the 15N-NMR spin relaxation data for both apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex. Data analysis began with determination of the global tumbling properties of both apo- and DNA-bound Pdx1. Application of an axially symmetric diffusion tensor was merited by the data, resulting in an effective isotropic correlation time (τc) of 5.8 ns and 12.6 ns for apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex, respectively; the axial ratio of the diffusion tensors was 1.28 and 1.29, respectively. NMR spin relaxation for several other homeodomain proteins has been documented in the literature, including for Pitx2, MATa1, and vnd/NK-2.39–41 In two of these three unbound-state cases, the reported τc was greater than the 5.8 ns correlation time we observe for apo-Pdx1. MATa1 homeodomain, which had a very similar mass to our Pdx1 construct, yielded a similar correlation time of 5.09 ns.39 The elevated correlation time observed for the Pdx1-DNACON complex is consistent with the complex’s increased mass and the magnitude we observed is comparable to the 11.5 ns correlation time reported for DNA-bound vnd/NK-2.40 Overall, our spin relaxation data are consistent with a monomeric state of both apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex in solution.

Modelfree analysis of the experimental spin relaxation data and iRED analysis42 of the molecular dynamics simulations yields qualitatively similar order parameter profiles (Figure 6). Overall, the order parameters suggest increased rigidity of Pdx1 in complex with DNA, although two specific regions merit additional discussion. Consistent with the known biochemistry of homeodomains, the Pdx1-DNA co-crystal structure suggests that the N-terminal residues of the Pdx1 homeodomain provide additional DNA sequence specificity by contacting the minor groove of DNA. In the apo-state, several of the N-terminal residues are not observed in the 1H,15N-HSQC due to the fast exchange of their amide protons with solvent (confirmed in experiments conducted at pH 6.5, in which these resonances are restored; data not shown). In the DNA-bound state, the N-terminal residues become protected from fast solvent exchange through their interactions with the minor groove of the DNA and therefore are observed in the 2D-spectra. Order parameters for the disordered N-terminal tail of the homeodomain are generally quite high in the Pdx1-DNACON complex, suggesting that the structure of this region, though irregular, is temporally stable in the complex. Additionally, the MD derived order parameters for the N-terminal arm of Pdx1 in complex with DNACON are in nearly quantitative agreement with the experimental results, which further supports the conclusion that the N-terminal arm interacts stably with the minor groove of the DNA in solution. Contrasting this data with the MD simulated order parameters of the apo-state suggests the N-terminal arm of apo-Pdx1 (which cannot be studied experimentally due to solvent exchange) is highly dynamic on the ps-ns timescale.

Figure 6.

Backbone amide generalized order parameters (S2) as a function of residue number for (A) apo-Pdx1 and (B) the Pdx1-DNACON complex. In both panels, the experimental order parameters are represented by colored circles attached with thin black lines, while those calculated from the Anton MD trajectories are represented as a thick black line. Experimental uncertainties in the order parameters are indicated as error bars, which often do not exceed the size of the markers on the plot. The secondary structure from the co-crystal of Pdx1 with a consensus DNA duplex is represented by bars above the figure.

In addition to the increased order of the N-terminal tail in the bound-state, the spin relaxation data reveal qualitative differences in the dynamics of the C-terminal turn of helix-3 in the apo-and DNA-bound states, as compared to the dynamics of the core secondary structure elements. Extensive fraying of the C-terminal turn of helix-3 during both the apo-Pdx1 and Pdx1-DNACON simulations manifests as lower order parameters in this region (Figure 6). As with the chemical shift data, the magnitude of unwinding predicted by simulation is in good agreement with the experimental values for apo-Pdx1 (Figure 6A). In addition, the enhanced fast timescale dynamics of the C-terminal turn of helix-3 suggested by the order parameter profile are corroborated by the raw heteronuclear NOE data seen in Figure 5C. Although the magnitude of fraying for the Pdx1-DNACON complex reported by decreased order parameters in the simulations is not quantitatively consistent with experiment (Figure 6B), the onset of fraying occurs at a similar location in both data sets. In these data, the dynamics of helix-3 begin to increase near Arg-198 in the unbound state and with Met-199 in the bound state. This correlates well with the simulated and experimental SSP calculations for both states and with the known role of Met-199 in forming interactions with the nucleobase at the 3´-position relative to the core TAAT sequence.

Given that the simulated fraying in the C-terminal end of helix-3 was shown to be qualitatively consistent with our experimental NMR results, we next analyzed the conformations of the C-terminus that were sampled over the course of the trajectories. Intriguingly, while the C-terminus is generally quite flexible and samples a wide range of orientations, it frequently samples conformations that trace the major groove of the DNA, in the vicinity of the CTC sequence found to the 5´-side of the core TAAT motif. In many frames of the trajectory, the side chain amine of Lys-203 interacts with the nucleobases of both the T·A base pair and the C·G base pair penultimate to the TAAT motif (an example of one such conformation is reported in the Supplemental Information, Figure S2). These are the only direct contacts observed between Pdx1 and the more distal base pairs to the 5´-side of the core TAAT motif and suggest that the C-terminal intrinsically disordered tail of Pdx1 may play a role in nucleobase recognition that complements the role played by Arg-150 of the N-terminal arm. Recall that our ITC studies revealed an approximately five-fold difference in Pdx1 affinity for the Insulin-A3 and IAPP-A1 elements, which differ only in the three base pairs to the 5´-side of the core TAAT motif, and that specificity provided by preference for a C·T base pair adjacent to the TAAT only accounted for about half of this difference. It is tempting to speculate that the interactions between Pdx1’s C-terminal tail and the 5´-side of the A-box motifs account for the difference in affinity between Pdx1 and insulin or iapp promoter-derived oligonucleotides, as observed in our ITC studies.

Taken together, our MD and NMR data suggest that the C-terminal end of helix-3 is less stable than indicated in the crystal structure, although the portion of the helix that forms the known DNA-interaction surface is well ordered in both the apo- and DNA-bound state. Our simulations also suggest that future studies of Pdx1 containing the full C-terminal tail may be merited, as this previously under-studied region may contribute to 3´-side nucleotide identification. In summary, the overall structural and dynamic description of apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex in our MD simulations compares favorably with experimental NMR data, suggesting that theses trajectories are well suited to generate a mechanistic hypothesis for the origin of sequence specificity observed in our ITC study.

Implications for insulin and iapp promoter interactions

Sequences similar to the consensus 5´-CTCTAAT(T/G)AG-3´ recognition element are commonly found in multiple copies throughout the proximal promoter regions of β-cell associated genes. Because many homeodomains bind a TAAT core recognition site, and because many homeodomains regulate expression from more than one promoter, interactions between peripheral nucleotide sequences and upstream amino acids are necessary to provide sequence discrimination. For example, the A-box elements contained within the insulin and iapp promoters vary systematically from one another on their 5´-sides, relative to the TAAT motif (Figure 1); although their 3´-sequences are highly similar. Pdx1 arrives early on both of these promoters and participates in the early organizational stages of their transcriptional programs.18,19 Therefore, even small differences in Pdx1 affinity for insulin and iapp promoter elements could exert strong control over the eventual expression levels of both proteins, providing a mechanism for maintenance of the functionally necessary high mole ratio of insulin to IAPP in pancreatic tissue and β-cell secretory granules.3,43

Motivated by Pdx1’s critical role within the endocrine pancreas, cellular and biochemical assays of Pdx1-DNA interactions have been reported regularly over the past two decades. Importantly, many early reports of promoter binding by Pdx1 in biochemical assays relied heavily on rat/mouse promoter sequences and did not address the effects of critical variations between these and human promoters.11,28,44,45 The rat insulin promoter is significantly dissimilar to the human promoter, with changes to the A3-box being particularly pronounced.21 Of relevance to the present study, there is a substitution of the 5´ position relative to the TAAT core in the rat and mouse insulin A1 element (5´-TTAAT-3´), compared to the more canonical 5´-CTAAT-3´ sequence seen in human. In other words, near the core TAAT element, some A-boxes in the rat insulin promoter appear more similar to the A-boxes of the human iapp promoter than they do to human insulin promoter elements. Given that we have shown these substitutions are thermodynamically significant, it is also important to establish a plausible model for the molecular origin of sequence recognition at this 5´-position.

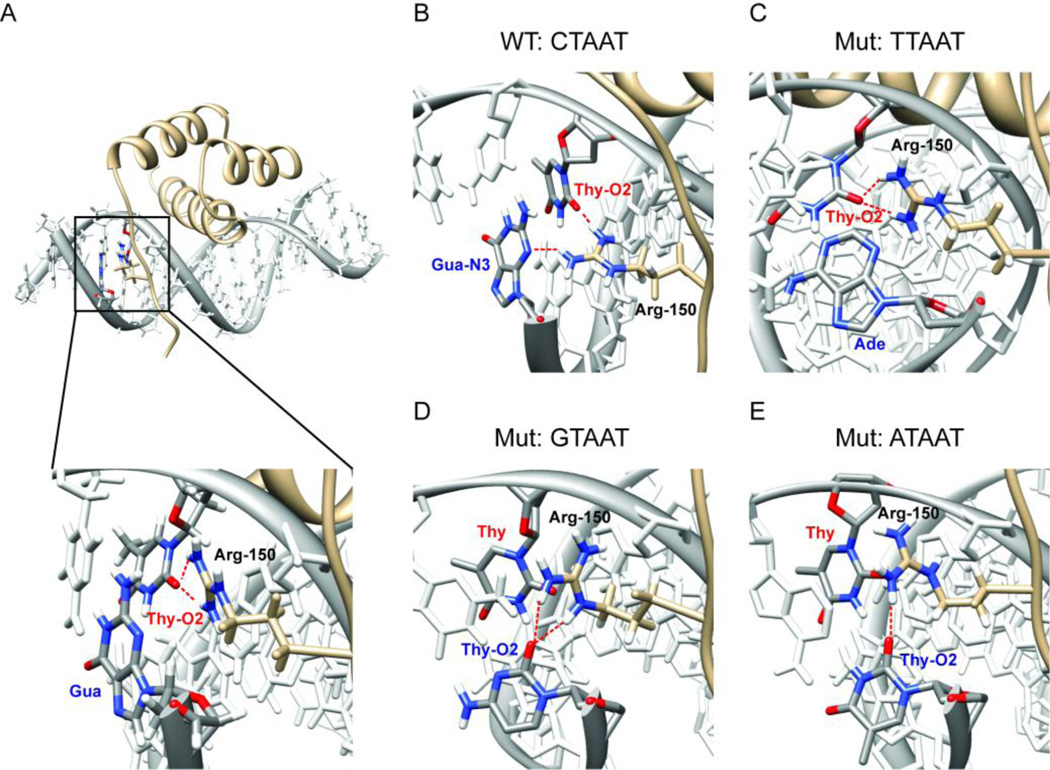

In the crystal structure of Pdx1 bound to a consensus DNA sequence, only the side chain of Arg-150 penetrates into the minor groove of the DNA duplex and makes direct contact with the nucleobases in the 5´-proximal region. By ITC, we have shown that Pdx1 has a modest preference for a C·G base pair in the 5´-position relative to the core motif. In order to provide a molecular rationale for this observation, we have extended our set of microsecond timescale MD simulations to include three trajectories where the 5´ base pair is systematically altered to T·A, G·C, and A·T. Simulation of the complex formed between Pdx1 and the consensus DNA containing a 5´ C·G base pair shows that Arg-150 is capable of achieving orientations that permit simultaneous hydrogen bonding to the O2 atom of the Thy in position 1 of the TAAT core motif and N3 of the guanine nucleobase on the opposing strand of the C·G base pair in the 5´-position relative to the core motif. Importantly, achieving the orientations necessary for the preferred hydrogen bonding arrangement does not lock Arg-150 into a single set of backbone and side chain torsional states. Instead, significant fluctuations along the aliphatic portion of the side chain can occur while the hydrogen bonding interactions are maintained (see Supplemental Information, Figures S3–S7, for plots of all Arg-150 torsion angles as a function of time for each of the five simulations). While the bridging interaction involving Arg-150 is remarkably stable in the Pdx1-DNA(CTAAT) simulation, no such stable interaction involving the nucleobases of the 5´-pair is observed for any of the other three Watson-Crick pairing combinations. For visual aid, the snapshot of each MD simulation recorded after 3.5 µs of production dynamics is shown in Figure 7, with the zoom set such that interactions between Arg-150, the 5´-pair, and the Thy in position 1 (Thy-1) of the TAAT motif are easily seen. In each panel, Arg-150, Thy-1, and the base occupying the opposing strand in the 5´-pair are shown in color, while the remainder of the DNA is represented in white.

Figure 7.

Reorientation of the Arg-150 side chain during the Anton MD simulations rationalizes the exclusive preference for a 5´ C·G base pair in sequences observed in the ITC study. For clarity, the Thy base from the TAAT sequence (labeled with a red ‘Thy’) and the nucleobase on the opposing strand in the 5´-flanking base pair (labeled with the appropriate three-letter code in blue) are displayed in color in all panels, whereas all other nucleobases are shown in white. Hydrogen bonds between Arg-150 (labeled in black) and the DNA nucleobases are indicated by dashed red lines. The nucleobase atom serving as a hydrogen bond acceptor is also designated in the color-coded nucleotide labels for the accepting bases. (A) The co-crystal structure of Pdx1 bound to consensus DNA shows Arg-150 to be the only residue capable of making direct contact with nucleotides 5´ to the core TAAT element. Contrary to the observation of selectivity for a C·G base pair observed by ITC, the co-crystal only shows Arg-150 in direct contact with the first T of the core element – no contact to the C·G base pair is made (inset). (B) During the Anton MD trajectory, Arg-150 rapidly reorients to simultaneously hydrogen bond with the Thy-O2 of the first position in the TAAT core element and with the Gua-N3 on the opposing strand in the 5´ C·G base pair. (C) Arg-150 retains a conformation similar to that of the co-crystal structure when Pdx1 is simulated in complex with the TTAAT mutant DNA, never making temporally stable contact with the 5´ T·A base pair. In both the (D) 5´ G·C and (E) 5´ A·T mutant trajectories, interactions of the Arg-150 side chain with nucleobase hydrogen-bond acceptors in the minor groove of the DNA duplex are especially unstable. In all cases, the snapshot recorded after 3.5 µs of production dynamics displays the predominant orientation of the Arg-150 side chain and is selected for representation.

In the crystallographic orientation, the only direct hydrogen bonds between a DNA nucleobase and the guanidino group of Arg-150 are formed to the O2 atom of Thy-1, as illustrated in Figure7A. This result contrasts with our ITC data, which show a subtle but clear preference for a C·G base pair in the 5´-position relative to the TAAT core. If Arg-150 is to sense the nucleotide identities in this pair, it is likely that thermally accessible fluctuations are able to drive reorientation of Arg-150 hydrogen bonding groups towards the 5´-pair. This is precisely what we observe; approximately 1 µs into the simulation, Arg-150 reorients such that it simultaneously hydrogen bonds to the O2 of Thy-1 (through the guanidino NH1 group) and the N3 of the 5´-Gua on the opposing strand (through the guanidino NH2 group). Once adopted, this orientation remains stable until fluctuations briefly drive the orientation back to a conformation more similar to the crystallographic orientation at around 2.5 µs of simulation time; but this transition is short lived and the bridging orientation is quickly resumed for the remainder of the simulation. The snapshot recorded at 3.5 µs of simulation time (shown in Figure 7B) is representative of the most stable orientation and illustrates the bridging interaction clearly.

From the 5´-CTAAT-3´ simulation alone, it is tempting to speculate that hydrogen bonding between the Arg-150 side chain and the N3 atom of any purine on the opposing strand, in the 5´-position relative to the TAAT core, is the primary determinant of the nucleotide preference of Arg-150. However, if this were true, a T·A pair in the 5´-position, as is observed in the iapp gene promoter, should provide equally strong binding – and yet our ITC data indicated this is not the case. Much to our surprise, in the Pdx1-DNA(TTAAT) simulation, Arg-150 retains a conformation similar to that of the co-crystal structure, never making temporally stable contact with the 5´ T·A base pair (as represented in Figure 7C).

Given the unexpected nature of the results from our calculations with a 5-TTAAT-3´ sequence, we next sought to determine the outcome of flipping the 5´-pair, producing the sequences 5-GTAAT-3´ and 5-ATAAT-3´. In these trajectories, Arg-150 appears to preferentially hydrogen bond to the exocyclic O2 of the pyrimidine in the strand opposing the TAAT motif, to the exclusion of interactions with Thy-1. In this case, the loss of stability is easy to rationalize from the structures in the trajectories, because Arg-150 is largely expelled from the minor groove in order to accommodate this hydrogen bond, which fluctuates between forming and breaking multiple times over the course of both trajectories. The representative structures at 3.5 µs of simulation time for the 5´ G·C and 5´ A·T mutants (shown in Figure 7D, E) illustrate this conformational transition clearly. Recall that in the ITC studies of binding to DNAcon, bearing mutations at the 5´-position, the binding enthalpy was less favorable for each of the three mutant sequences, as compared with the enthalpy observed for binding to the wild-type 5´-CTAAT-3´ consensus. Partial expulsion of Arg-150 from the minor groove in the presence of the 5´ G·C or 5´ A·T base pairs, with only transient hydrogen bonding to the pyrimidine O2, is consistent with the loss of stabilizing binding enthalpy. On the other hand, binding to the iapp-type consensus element containing a 5-TTAAT-3´ sequence, and binding to iapp-derived native sequences, also occurs with a significantly less favorable binding enthalpy, as compared to insulin promoter or DNAcon sequences. This key result is more challenging to rationalize based solely on hydrogen bond geometry.

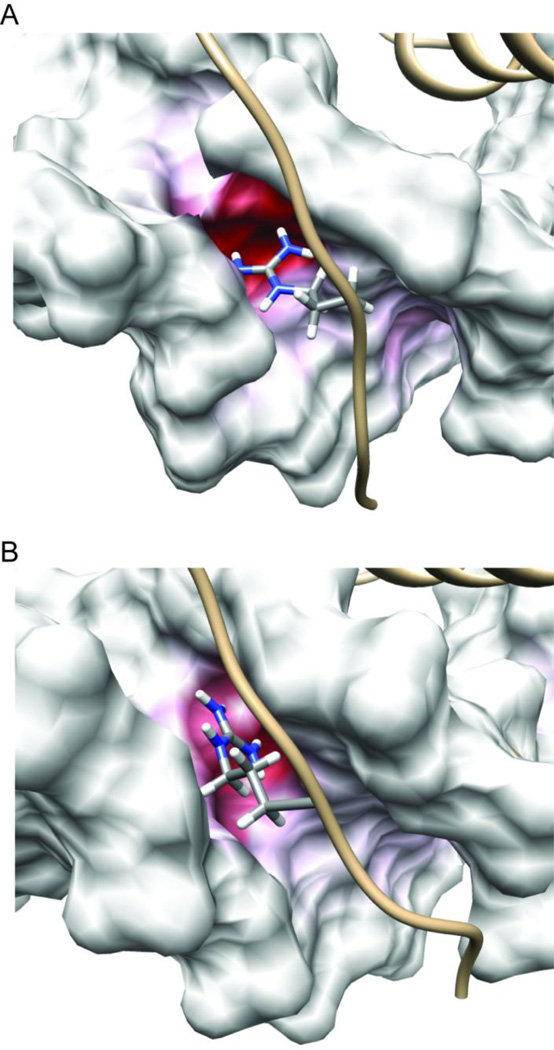

These data suggested to us that an additional factor, beyond stable penetration into the minor groove and hydrogen bonding to Thy-1, is important for determining 5´-pair specificity. We note that, in our simulations of Pdx1-DNA(CTAAT), Arg-150 reoriented to interact with the Gua-N3 in the opposing strand of the 5´-position, but not the Ade-N3 when the 5´ T·A mutation was made. Therefore, we investigated whether the nature of the minor groove itself is different between consensus DNA harboring the preferred 5´ C·G and the less favorable 5´ T·A. As both of these base pairs are sterically similar and present a similar pattern of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors in the minor groove, we turned to calculations of the surface electrostatics in the minor groove as a possible explanation for our binding data.

The results of our electrostatic calculations are shown using the 3.5 µs snapshot from the Pdx1-DNA(CTAAT) (insulin-like; Figure 8A) and Pdx1-DNA(TTAAT) (iapp-like; Figure 8B) trajectories in Figure 8. Given that the entire surface of the DNA duplex bears a strong negative charge, mapping of electrostatic charge onto the molecular surface has been colorized such that the majority of the DNA appears in white, with only those regions that are anomalously negative in charge trending towards deep red. Visualizing the surface charge of the DNA in this way immediately leads to the prediction that binding to the 5-CTAAT-3´ (insulin-like) sequences is enthalpically favorable over binding to 5-TTAAT-3´ (iapp-like) sequences. This prediction is consistent with our thermodynamic data, which show a steep and unfavorable change in the binding enthalpy of iapp-derived sequences, as compared to those derived from the insulin promoter or the consensus sequence. The deep red pocket occupied by Arg-150 in Figure 8A spans both Thy-1 and the 5´ C·G pair. Throughout the trajectory, Arg-150 preferentially orients within this pocket, while simultaneously maintaining the bridging hydrogen bond geometry previously discussed. In contrast, replacement of the 5´ C·G pair with a 5´ T·A pair interposes the partial positive charge on the six membered ring of the Ade nucleobase, resulting in a collapse of the strongly negative pocket to only include the first base pair of the core TAAT motif. Although hydrogen bonding to the Ade-N3 in a bridging conformation reminiscent of that observed with a 5´-CTAAT-3´ (insulin-like) sequence is sterically possible, the side chain of Arg-150 does not form this interaction. Instead, Arg-150 remains oriented towards the strongly negative pocket primarily including the first base pair of the TAAT motif.

Figure 8.

The Arg-150 side chain δ-guanidino group inserts into a strongly negative patch within the minor groove of the DNA duplex and reorients to track the position of maximum negative charge. The surface electrostatic potential of the DNA, calculated with Pdx1 removed, is mapped onto snapshots from Anton MD trajectories of (A) the Pdx1-DNACON complex and (B) the Pdx1-DNA(TTAATG) complex. In both cases, the snapshot recorded after 3.5 µs of production dynamics is selected for representation. In order to emphasize the strong negative charge of the Arg-150 binding pocket, even compared with the general charge on a DNA duplex, the color scale of the DNA surface for both panels is −14 kT/e (red) to 0.0 kT/e (white). The side chain atoms of Arg-150 are represented in CPK mode, and colored by atom type (grey, carbon; blue, nitrogen; white, hydrogen).

Conclusions

Among its many functions, Pdx1 maintains glucose homeostasis by regulating transcription of both the insulin and iapp genes, through interactions with A-box elements in their promoters. Collectively, the data presented here provide a clear hypothesis for the molecular origins of A-box specificity inherent to the Pdx1-DNA binding mode. The binding specificity of Pdx1 for regulated promoter elements is dominated by the presence of a TAAT sequence, which alone does not provide enough information to impart specificity. Our thermodynamic results quantify Pdx1’s preference for Cyt in the 5´-position, relative to the TAAT core, which is fundamental to its differential affinity for the insulin and iapp promoters. Analysis of microsecond timescale MD simulations, which have been vetted through their ability to reproduce experimental NMR data, reveals a plausible mechanism for the observed sequence-specificity. Our study demonstrates that Pdx1 is able to reject A·T and G·C base pairs at the 5´ position, relative to the TAAT core, because interactions between Arg-150 and the minor groove of the DNA become unstable in this context. More significantly, our study demonstrates that Pdx1 is able to discriminate between insulin and iapp promoter-derived sequences based on the electrostatic potential created by juxtaposition of their respective 5´-flanking residues with the first T·A pair of the core TAAT sequence, due to preferential electrostatic stabilization of the highly conserved Arg-150 in an orientation that favors hydrogen bonding with the 5´-flanking pair when sequences similar to those found in the human insulin promoter are bound.

Materials and Methods

Protein Preparation and Purification

A synthetic Pdx1 gene was purchased from Geneart and the Pdx1 homeodomain (amino acids 146–206 of the human sequence; subsequently referred to as Pdx1-HD), was subcloned by PCR into pET47b (Novagen) encoding a 6× His tag and a 3C protease recognition site upstream of the cloning site. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3) competent cells for protein over-expression. Pdx1-HD for ITC was harvested from cells grown in LB media at 37 °C until an OD of 0.8–1.0 was reached, at which time expression was induced with a final IPTG concentration of 0.5 mM and the temperature reduced to 30 °C. Pdx1-HD for NMR spectroscopy was harvested from cells grown in M9 minimal media, made with 15NH4Cl and either 13C-glucose for backbone assignment or 12C-glucose for spin relaxation measurements. The cells were incubated at 37 °C until an OD of 0.5–0.7 was reached and expression was induced with a final IPTG concentration of 0.5 mM and the temperature reduced to 30 °C. In all cases, cells were harvested 4 hours post-induction and lysed by sonication at 4 °C. The suspension was centrifuged at 4 °C for 30 min at 11500 rpm in a Beckman Coulter Allegra 25R using a TA-14–50 rotor. The supernatant was passed over a Ni-NTA (Novagen) column, and the protein was eluted with imidazole (200 mM). The 6× His-tag was cleaved by incubating with 3C protease at 4°C overnight while also dialyzing away the imidazole. The contents of the dialysis bag were passed over the same NTA-Ni column, and the flow-through was collected. The protein was concentrated using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter device (Millipore) that contained a PES 3000 MWCO membrane. The homeodomain was buffer exchanged into the storage buffer (100 mM cacodylate, pH 7.3, and 100 mM potassium chloride). Protein concentrations were determined by UV absorption at 278 nm in denaturing conditions (final concentrations of 6.1 M Guanidinium Chloride, pH 7.5) using the extinction coefficient of 14,000 M−1 cm−1.

Duplex DNA Preparation for ITC

All DNA was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc (for sequences of the forward-strand see Tables 1 and 2; all oligonucleotides were purchased with sequences providing perfect Watson-Crick complementarities). ssDNA concentrations were determined based on the IDT calculated extinction coefficients. Duplex formation was accomplished by heating complementary ssDNA in a water bath and slowly cooling to room temperature. Duplex DNA concentrations were quantified by standard UV absorbance assay at 260 nm. Finally, duplex DNA was dialyzed overnight in storage buffer.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

All binding studies were performed at 25 °C using standard protocols,46 adapted for running on an Auto-ITC200 (MicroCal, Inc.). Prior to ITC, duplex DNA and Pdx1-HD were co-dialyzed overnight in storage buffer (100 mM cacodylate, pH 7.3, and 100 mM potassium chloride). 1.2 – 1.5 µL of Pdx1 homeodomain (60 or 100 µM) were injected into 16-mer duplex DNA (6 or 10 µM) at 220 second intervals while the contents of the cell were stirred at a speed of 1000 rpm. The heat of ligand dilution was accounted for by averaging the final five points of each titration and subtracting the average from each point in the titration. ITC experiments for each duplex were completed at the least in triplicate and the averages of the best-fit parameters from a single-site binding model are reported with their associated uncertainties represented by the standard error of the mean. All data was fit in Origin 7.0 (MicroCal, Inc.).

Anton Simulations of Pdx1

Starting coordinates for all Pdx1 trajectories were derived from the crystal structure of the Pdx1 homeodomain bound to duplex DNA (pdb 2h1k; b, e, and f chains used).24 The DNA in this starting structure is similar to the consensus duplex used in our experimental studies except for the presence of a single-nucleotide 5´ overhang on both strands; for the wild-type DNA trajectory, the sequence of the DNA simulated was 5´-TCTCTAATGAGTTTC-3´ in complex with 5´-AGAAACTCATTAGAG-3´. The apo-Pdx1 simulation was initiated using the Pdx1 coordinates from the holo-state crystal structure, but with the DNA eliminated; Pdx1-DNA(WT) was initiated directly from the co-crystal structure. Simulations with substituted Watson-Crick base pairs in the 5´-position relative to the TAAT core recognition site were generated from the wild-type co-crystal structure using the Amber nucleic acid builder.47 Systematic variation of the base pair composition at the 5´-position in the wild type DNA(CTAATG) sequence resulted in three DNA-mutant trajectories, denoted throughout the text as Pdx1-DNA(ATAATG), Pdx1-DNA(GTAATG), and Pdx1-DNA(TTAATG).

All-atom molecular simulations of apo-Pdx1 and Pdx1 in complex with duplex DNA of varying composition were conducted using the ff99SB Amber force field48 on Anton,32 a special-purpose machine for molecular mechanics. For all simulations, the starting conformation of Pdx1 or the Pdx1-DNA complex was embedded in a cubic box of SPC water molecules with a bulk sodium chloride concentration of 100 mM. For apo-Pdx1, this resulted in an initial box roughly 62 Å to a side, containing 14 Na+ and 23 Cl− ions (to neutralize the system), and 7,449 water molecules. Each of the four Pdx1-DNA complexes was embedded in a box that began approximately 77.4 Å to a side, containing 46 Na+ and 27 Cl− ions, and approximately 14,500 water molecules. The systems were prepared in Maestro for energy minimization and temperature equilibration in an NVT ensemble for a total of 1.2 ns in Desmond (D.E. Shaw Research). Subsequently, each simulation was equilibrated in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 bar; Berendsen coupling scheme) for a minimum of 5 ns. All bond lengths to hydrogen atoms were constrained using SHAKE. Production dynamics were run under the same NPT conditions with SHAKE, using a 2.0 fs timestep (long-range electrostatics computed every 6.0 fs). Each simulation was run for a minimum of 5.0 µs of production dynamics. Prior to analysis, snapshots that were stored to disk every 200 ps were stripped of waters using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD),49 which was also used for preliminary trajectory visualization.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis

Molecular graphics images were created using the UCSF Chimera package.50 Additional analysis and visualization were accomplished in MATLAB (MathWorks). MD-derived order parameters were obtained by using iRED analysis42 of MD trajectories averaged over 5 ns windows, as previously reported.51 Backbone carbon chemical shifts were calculated from the MD ensemble using the SHIFTS program,52 following the protocol of Li and Brüschweiler.53

Nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann Analysis

Electrostatic potential calculations were carried out using numerical solutions to the nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann equation, as implemented in the adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann solver (APBS)54 plug-in to PyMOL.55 Settings were chosen as described by Veeraraghavan et al.;56 briefly, the DNA from each analyzed snapshot was placed in a medium with a dielectric constant of 2.0 within the solvent-accessible surface-enclosed volume and dielectric constant 80 within the continuum solvent containing 0.15M monovalent ions.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

In all samples for NMR spectroscopy, the concentration of Pdx1-HD was approximately 200 µM and, when present, DNA was added to two-fold molar excess, yielding concentrations near 400 µM. Chemical shift assignments were generated using samples buffer exchanged into 20 mM cacodylate, pH 6.5, and 100 mM potassium chloride in 10% D2O (v/v); all spectra were recorded at 298K. Standard triple resonance NMR techniques were used to assign all resonances of Pdx1-HD (apo) and DNA bound Pdx1-HD (holo) on a BrukerAvance III 500 and 850 MHz spectrometers.57 Both spectrometers were equipped with TCI cryroprobes for maximum sensitivity. Spectra were processed by NMRpipe and analyzed with SPARKY (SPARKY 3.113; T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, University of California, San Francisco, CA). Relaxation data were analyzed in Matlab (MathWorks). Backbone chemical shifts for both states were assigned and have been deposited in the BMRB (ID number 19227 for apo-Pdx1 and 19228 for the Pdx1-DNAconcomplex). The change of 2D peak position in the 1H,15N-HSQC spectra for apo-Pdx1 and the Pdx1-DNACON complex is quantified as:

| (1) |

where Δppm is the change in chemical shift between the two states and α = 0.1 normalizes the 15N and 1H chemical shift ranges.

Experiments measuring 15N T1 and T2 spin relaxation, as well as the 1H-15N NOE, were performed at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer using standard 15N relaxation methods.35,36 Relaxation decays of T1 were generated by acquiring a set of ten spectra with delays, 50, 150, 150, 250, 350, 450, 550, 550, 650, and 750 ms. T2 relaxation decays were obtained by using 16, 48, 48, 80, 112, 144, 176, and 208 ms delays. Heteronuclear NOE experiments were acquired in duplicate using a 5 second saturation period for NOE transfer (and a matching time delay in the control experiment). Solution conditions for the spin relaxation samples were chosen to match the conditions used for ITC measurements (100 mM cacodylate, pH 7.3, and 100 mM potassium chloride), except for the addition of 10% D2O (v/v) to the NMR samples.

Modelfree Analysis

Lipari-Szabo modelfree analysis was performed using modelfree4.20,58 with diffusion tensor fitting using the quadric method59,60 and in-house written Matlab scripts as previously described.61 The x-ray crystal structure of Pdx1-HD (pdb 2h1k)24 was modified to remove the DNA and used as the structural reference for axially symmetric diffusion tensor estimation. The 15N T1, T2, and 1H-15N NOE data were fit using the axially symmetric global diffusion parameters established through the quadric protocol, with S2 and τe (model 2) describing internal motions for each site.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Does Pdx1 differentiate between insulin and iapp promoter elements? If so, how?

Preference for CTAAT (insulin) is established over TTAAT (iapp) by ITC.

NMR dynamics support docking of the N-terminal arm of Pdx1 into the minor groove.

MD simulations rationalize N-terminal arm’s role in establishing specificity.

A mechanism for preference towards insulin over iapp promoter elements is proposed.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Neela Yennawar and Julia Fecko for assistance with the Auto-ITC200, and Dr. Debashish Sahu for helpful discussions of homeodomain-DNA interactions and function. This work was supported by an NIH predoctoral fellowship to M.B. (F31GM101936) and by start-up funds provided to S.A.S. by the Pennsylvania State University. The Anton machine at NRBSC/PSC was generously made available by D.E. Shaw Research. Anton computer time was provided by the National Resource for Biomedical Supercomputing (NRBSC) and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC) through Grant RC2GM093307 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- dsDNA

double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid

- HD

homeodomain

- HSQC

heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- IAPP

islet amyloid polypeptide

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-tiogalactopranoside

- iRED

isotropic reorientational eigenmode dynamics

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MHz

megahertz

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- NTA

nitrilotriacetic acid

- Pdx1

pancreatic-duodenal homeobox protein 1

- ssDNA

single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid

- SSP

secondary structure propensity

- UV

ultraviolet

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Throughout this paper we use numbering that indicates a residue’s position within the human Pdx1 sequence. Residue 1 of the canonical 60 residue homeodomain sequence corresponds to residue number 146 of Pdx1.

References

- 1.Sander M, German MS. The beta cell transcription factors and development of the pancreas. J Mol Med. 1997;75:327–340. doi: 10.1007/s001090050118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutton JC, Penn EJ, Peshavaria M. Isolation and characterisation of insulin secretory granules from a rat islet cell tumour. Diabetologia. 1982;23:365–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00253746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suckale J, Solimena M. The insulin secretory granule as a signaling hub. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa A, Harris V, McCorkle SK, Unger RH, Luskey KL. Amylin secretion from the rat pancreas and its selective loss after streptozotocin treatment. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:973–976. doi: 10.1172/JCI114528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westermark P, Andersson A, Westermark GT. Islet amyloid polypeptide, islet amyloid, and diabetes mellitus. Physiological reviews. 2011;91:795–826. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akesson B, Panagiotidis G, Westermark P, Lundquist I. Islet amyloid polypeptide inhibits glucagon release and exerts a dual action on insulin release from isolated islets. Regul Pept. 2003;111:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutz TA. Control of energy homeostasis by amylin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1947–1965. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0905-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rushing PA, Hagan MM, Seeley RJ, Lutz TA, Woods SC. Amylin: a novel action in the brain to reduce body weight. Endocrinology. 2000;141:850–853. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.2.7378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutz TA. Amylinergic control of food intake. Physiology & behavior. 2006;89:465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woerle HJ, Albrecht M, Linke R, Zschau S, Neumann C, Nicolaus M, Gerich JE, Goke B, Schirra J. Impaired hyperglycemia-induced delay in gastric emptying in patients with type 1 diabetes deficient for islet amyloid polypeptide. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2325–2331. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.German MS, Moss LG, Wang J, Rutter WJ. The insulin and islet amyloid polypeptide genes contain similar cell-specific promoter elements that bind identical beta-cell nuclear complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1777–1788. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.German M, Ashcroft S, Docherty K, Edlund H, Edlund T, Goodison S, Imura H, Kennedy G, Madsen O, Melloul D, et al. The insulin gene promoter. A simplified nomenclature. Diabetes. 1995;44:1002–1004. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.8.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernardo AS, Hay CW, Docherty K. Pancreatic transcription factors and their role in the birth, life and survival of the pancreatic beta cell. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;294:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glick E, Leshkowitz D, Walker MD. Transcription factor BETA2 acts cooperatively with E2A and PDX1 to activate the insulin gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2199–2204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cissell MA, Zhao L, Sussel L, Henderson E, Stein R. Transcription factor occupancy of the insulin gene in vivo. Evidence for direct regulation by Nkx2.2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:751–756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohneda K, Mirmira RG, Wang J, Johnson JD, German MS. The homeodomain of PDX-1 mediates multiple protein-protein interactions in the formation of a transcriptional activation complex on the insulin promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:900–911. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.900-911.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serup P, Jensen J, Andersen FG, Jorgensen MC, Blume N, Holst JJ, Madsen OD. Induction of insulin and islet amyloid polypeptide production in pancreatic islet glucagonoma cells by insulin promoter factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9015–9020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakrabarti SK, James JC, Mirmira RG. Quantitative assessment of gene targeting in vitro and in vivo by the pancreatic transcription factor, Pdx1. Importance of chromatin structure in directing promoter binding. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13286–13293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macfarlane WM, Campbell SC, Elrick LJ, Oates V, Bermano G, Lindley KJ, Aynsley-Green A, Dunne MJ, James RF, Docherty K. Glucose regulates islet amyloid polypeptide gene transcription in a PDX1- and calcium-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15330–15335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908045199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller CP, McGehee RE, Jr, Habener JF. IDX-1: a new homeodomain transcription factor expressed in rat pancreatic islets and duodenum that transactivates the somatostatin gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:1145–1156. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberzon A, Ridner G, Walker MD. Role of intrinsic DNA binding specificity in defining target genes of the mammalian transcription factor PDX1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:54–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hay CW, Docherty K. Comparative analysis of insulin gene promoters: implications for diabetes research. Diabetes. 2006;55:3201–3213. doi: 10.2337/db06-0788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babu DA, Deering TG, Mirmira RG. A feat of metabolic proportions: Pdx1 orchestrates islet development and function in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;92:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longo A, Guanga GP, Rose RB. Structural basis for induced fit mechanisms in DNA recognition by the Pdx1 homeodomain. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2948–2957. doi: 10.1021/bi060969l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.German MS, Wang J. The insulin gene contains multiple transcriptional elements that respond to glucose. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4067–4075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacFarlane WM, Read ML, Gilligan M, Bujalska I, Docherty K. Glucose modulates the binding activity of the beta-cell transcription factor IUF1 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Biochem J. 1994;303(Pt 2):625–631. doi: 10.1042/bj3030625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor DG, Babu D, Mirmira RG. The C-terminal domain of the beta cell homeodomain factor Nkx6.1 enhances sequence-selective DNA binding at the insulin promoter. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11269–11278. doi: 10.1021/bi050821m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francis J, Babu DA, Deering TG, Chakrabarti SK, Garmey JC, Evans-Molina C, Taylor DG, Mirmira RG. Role of chromatin accessibility in the occupancy and transcription of the insulin gene by the pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3133–3145. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ades SE, Sauer RT. Specificity of minor-groove and major-groove interactions in a homeodomain-DNA complex. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14601–14608. doi: 10.1021/bi00044a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klepeis JL, Lindorff-Larsen K, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of protein structure and function. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dror RO, Dirks RM, Grossman JP, Xu H, Shaw DE. Biomolecular simulation: a computational microscope for molecular biology. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:429–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw DE, Deneroff MM, Dror RO, Kuskin JS, Larson RH, Salmon JK, Young C, Batson B, Bowers KJ, Chao JC, Eastwood MP, Gagliardo J, Grossman JP, Ho CR, Ierardi DJ, Kolossvary I, Klepeis JL, Layman T, Mcleavey C, Moraes MA, Mueller R, Priest EC, Shan YB, Spengler J, Theobald M, Towles B, Wang SC. Anton, a special-purpose machine for molecular dynamics simulation. Commun Acm. 2008;51:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Billeter M, Qian YQ, Otting G, Muller M, Gehring W, Wuthrich K. Determination of the nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of an Antennapedia homeodomain-DNA complex. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:1084–1093. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh JA, Singh VK, Jia Z, Forman-Kay JD. Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between alpha- and gamma-synuclein: implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2795–2804. doi: 10.1110/ps.062465306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer AG., 3rd NMR characterization of the dynamics of biomacromolecules. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3623–3640. doi: 10.1021/cr030413t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jarymowycz VA, Stone MJ. Fast time scale dynamics of protein backbones: NMR relaxation methods, applications, and functional consequences. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1624–1671. doi: 10.1021/cr040421p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]