TGF-β plus rapamycin-induced regulatory T cells (iTreg) are comparable to iTreg induced with TGF-β plus retinoic acid in their suppressive capacity, but reveal distinct migration patterns in vivo that affect their therapeutic use.

Keywords: Treg migration, chemokines, adoptive cell therapy, inflammatory bowel disease, live-animal imaging

Abstract

Tregs play important roles in maintaining immune homeostasis, and thus, therapies based on Treg are promising candidates for the treatment for a variety of immune-mediated disorders. These therapies, however, face the significant challenge of obtaining adequate numbers of Tregs from peripheral blood that maintains suppressive function following extensive expansion. Inducing Tregs from non-Tregs offers a viable alternative. Different methods to induce Tregs have been proposed and involve mainly treating cells with TGF-β-iTreg. However, use of TGF-β alone is not sufficient to induce stable Tregs. ATRA or rapa has been shown to synergize with TGF-β to induce stable Tregs. Whereas TGF-β plus RA-iTregs have been well-described in the literature, the phenotype, function, and migratory characteristics of TGF-β plus rapa-iTreg have yet to be elucidated. Herein, we describe the phenotype and function of mouse rapa-iTreg and reveal that these cells differ in their in vivo homing capacity when compared with mouse RA-iTreg and mouse TGF-β-iTreg. This difference in migratory activity significantly affects the therapeutic capacity of each subset in a mouse model of colitis. We also describe the characteristics of iTreg generated in the presence of TGF-β, RA, and rapa.

Introduction

Treg-based therapies are widely regarded as promising treatment options for autoimmune disease and transplant rejection [1–3]. Currently, several therapies involving the use of ex vivo-expanded Tregs are being tested in clinical trials [2, 4, 5]. However, there are significant barriers to ex vivo Treg-based therapies, such as difficulty in isolating pure populations of these rare cells and expanding them to sufficiently large numbers, while maintaining their phenotype and function [2, 6].

One possible alternative to circumvent these issues is to generate adaptive Tregs or iTregs from the patient's own naive T cells, ex vivo or in vivo. Past reports [7, 8] have demonstrated that IL-2 and TGF-β1 can induce a Treg phenotype and functional characteristics in naive T cells upon in vitro stimulation. However, TGF-β-iTregs have been shown to be unstable in long-term in vitro culture and upon antigenic restimulation [9]. Additionally, the presence of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, can antagonize TGF-β-mediated induction of Tregs [10, 11], making the presence of such inflammatory mediators at the site of the disease a potential impediment to inducing Tregs in vivo.

Numerous reports suggest that these problems can be overcome through the use of small molecules that work in concert with TGF-β to induce Tregs. For example, ATRA is known to potently synergize with IL-2 and TGF-β to induce FoxP3 expression in naive mouse T cells [12–14] and allows for induction of Tregs, even in the presence of inflammatory cytokines. Thorough characterization of the phenotype and function of Tregs induced in the presence of IL-2, TGF-β and RA (RA-iTreg) demonstrates that they are better suppressors and more stable than TGF-β-iTregs [12, 14]. Nevertheless, RA-iTregs migrate primarily to mucosal tissue in the gut [12, 14], which might limit their use. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that depending on the immunological microenvironment, RA can induce inflammation rather than tolerance [15]. Also, RA has been shown to induce hypervitaminosis-A upon local administration [16, 17], and hence, it would be difficult to use this combination (cytokines+RA) to induce Tregs in vivo. Another small molecule that synergizes with IL-2 and TGF-β to induce FoxP3 expression in naive T cells is the serine/threonine protein kinase inhibitor rapa [18–20]. Although it has been demonstrated that, like RA, rapa can induce Tregs in mice, even in the presence of IL-6 [18], the phenotype and function of Tregs, induced in the presence of IL-2, TGF-β, and rapa (rapa-iTreg), are yet to be characterized.

In this study, we compare and contrast the phenotype (expression of canonical Treg markers and surface migratory markers), function, and stability of TGF-β-iTreg, RA-iTreg, and rapa-iTreg upon in vitro restimulation. Our data suggest that the combination of IL-2, TGF-β, and rapa induces Tregs with greater functional stability when compared with TGF-β-iTregs. Additionally, rapa-iTregs possess a relatively greater lymphoid tissue-homing capacity when compared with RA-iTregs that migrate primarily to the gut. This different migratory pattern correlates with a stronger protective capacity of rapa-iTregs over RA-iTregs when compared for their ability to delay disease onset in a mouse model of T cell-induced colitis. Additionally, we describe the characteristics of a new iTreg population generated by combining IL-2, TGF-β, RA, and rapa (RA+rapa-iTreg).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and under University of Pittsburgh Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols (University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Protocol Numbers 0909675 and 1002709).

Animals

Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 and B6.SJL-Ptprca/BoyAiTac (CD45.1) mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY, USA) and used within 2 months of delivery. B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J (albino C57BL/6 mice) and B6.Cg-FoxP3tm2Tch/J (FoxP3-EGFP mice) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and bred in our facility, together with C57BL/6-Rag2-KO mice. C57BL/6.Luc+ mice were a kind gift from Dr. Stephen Thorne (Dept. of Surgery, University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA). All animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions.

Materials

A mouse CD4-negative isolation kit, αCD3/αCD28-labeled beads (aAPC Dynal), and Vybrant CFDA-succinimidyl ester cell tracer kit were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Mouse rIL-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), human rTGF-β1 (CHO cell-derived; PeproTech, Rocky Hills, NJ, USA), ATRA acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and rapa (LC labs, Woburn, MA, USA) were purchased from the appropriate supplier. The following antibodies were obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA): CD4 (L3T4), FoxP3 (FJK-16s), CD45.1 (A20), CD103 (2E7), CD25 (PC61.5), GITR protein (DTA-1), FR4 (eBio12A5), CCR7 (4B12), and CCR9 (eBioCW-1.2). Anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 CTLA-4 (UC10-4B9) was from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-PE microbeads were obtained from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA, USA).

T cell isolation

Spleens and LNs were dissected from mice and single-cell suspensions prepared using mechanical digestion. Following red blood cell lysis, CD4+ cell isolation was performed using the CD4-negative isolation kit (Invitrogen), as per the manufacturer's instructions. To enrich for CD25− cells, CD4+ cells were incubated with anti-mouse CD25-PE antibody (eBioscience), followed by addition of anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Bead-bound CD25+ cells were isolated by passing cells through a magnetic column. Unbound CD4+ CD25− cells were separated and used to induce Tregs. Over 95% of the obtained cells expressed the CD4R, and <2% of the cells expressed FoxP3. Bead-bound CD4+ CD25+ cells, considered nTreg, were used as controls in in vitro suppression assays. Approximately 85% of the CD4+ CD25+ cells expressed FoxP3.

Treg induction

Freshly isolated, naive CD4+ CD25− cells were cultured with aAPC Dynal beads at a 2:1 (dynal:cell) ratio in the presence of 10 ng/ml IL-2, 20 ng/ml TGF-β1, and/or 3 ng/ml (10 nM) RA and/or 10 ng/ml rapa. To obtain Teff, CD4+ CD25− cells were cultured with aAPC Dynal beads and 10 ng/ml IL-2 only. Cell cultures were maintained for 4 days, and cells separated subsequently from the magnetic Dynal beads. To determine induction of Treg phenotype, FoxP3 staining and flow cytometry (BD LSRII) were performed at the end of the 4-day culture period, as per the manufacturer's instructions (eBioscience).

In vitro suppression assay

Freshly isolated, naive CD4+ CD45.1+ cells were stained with CFSE (Invitrogen; per the manufacturer's instructions) and cocultured with autologous iTregs (generated as described above) at different ratios in 96-well plates. The number of naive CD4+ CD45.1+ cells was always 50,000 cells/well. For stimulation, 25,000 aAPC Dynal beads/well were used (2:1, naive cell:Dynal ratio). Cocultures were maintained for 4 days, followed by staining for flow cytometry. Quantification of T cell proliferation (or inhibition thereof) was determined through analysis of the resulting CFSE dilution profile, as interpolated by ModFit LT analysis software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA).

Testing iTreg stability in vitro

iTregs, generated under different conditions (Teff generated by stimulating naive T cells from CD45.2 mice in the presence of IL-2 only), were obtained from 4-day cultures and rested in 10 ng/ml IL-2 for 2 days. Thereafter, the cells were cultured along with aAPC Dynal beads as stimulators: (1) for Dynal only [no Teff and no factors (TGF-β, rapa, or RA)] group, 100,000 iTregs were cultured with 200,000 Dynal along with 10 ng/ml IL-2; (2) for Dynal + Teff (no factors) group, 50,000 iTregs were cultured with 50,000 Teff and 100,000 Dynal along with 10 ng/ml IL-2; (3) for Dynal + factors (no Teff) group, 100,000 iTregs were cultured with 200,000 Dynal and respective factors at the concentrations described above; and (4) for Dynal + Teff + factors group, 50,000 iTregs were cultured with 50,000 Teff and 100,000 Dynal and respective factors. Restimulation experiments were carried out for 4 days, and cells were then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vivo migration experiments

iTregs generated from naive CD45.1+ CD4+ CD25− cells were injected into CD45.2 mice at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells in 200 μl PBS/animal (lateral tail vein). Three days following injection, mice were killed and the spleen, cervical LNs, and mesenteric LNs collected. Single-cell suspensions from each of these tissues were prepared, stained for different markers, and analyzed by flow cytometry. For in vivo live animal imaging experiments, iTregs were generated from C57BL/6.Luc+ mice and injected into albino C57BL/6 mice at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells in 200 μl PBS/animal (lateral tail vein). At defined time-points, mice were injected (i.p.) with 200 μl luciferin (30 mg/ml) and imaged using the IVIS 200 (Xenogen VivoVision, Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA). Luminescent images were analyzed and quantified using Igor Pro Living Image 2.60.1 (Caliper Life Sciences).

In vivo suppression experiments

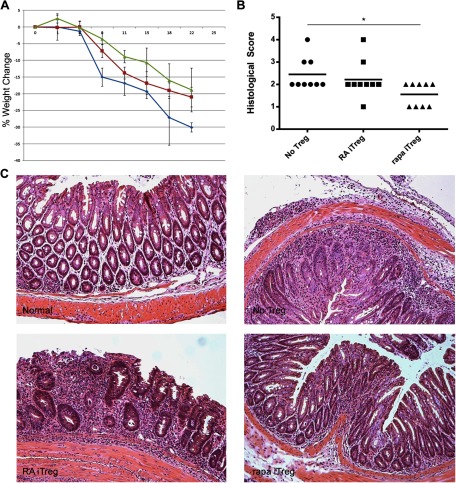

CD4+ CD25− T cells were isolated from FoxP3-EGFP mice and converted to RA- or rapa-iTregs, as described above. Expanded cells were flow-sorted postculture, based on expression of EGFP (restricted to FoxP3+ Tregs). One million CD4+ CD25− T cells (from an unrelated B6 mouse) and 1 million or 2.5 × 105 RA- or rapa-EGFP+ iTregs were injected i.v. into each Rag2-KO host. Control mice received 1 million CD4+ CD25− T cells only. A first cohort of mice was weighed every 2 days to monitor weight changes. A second group of identically treated recipients was killed on Day 8 after injection, and the proximal, middle, and distal portions of the colons were prepared for histological analysis.

Histological analysis of colon sections

Paraffin-embedded sections, obtained from recipient mice colons, were prepared by the Histology Core of the STI (University of Pittsburgh) and stained with H&E. The degree of inflammation in cross-sections of the colon was graded by the same pathologist in a blinded manner. Pictures were taken using a 10× objective on a Zeiss Axiostar Plus microscope, equipped with an AxioCam MRc camera and controlled by AxioVision software. Histology was scored on a 0–5 scale, with the numbers implying the following: Score 0, no change (normal); Score 1, minimal scattered mucosal inflammatory cell infiltrates, with or without minimal epithelial hyperplasia; Score 2, mild scattered to diffuse inflammatory cell infiltrates, sometimes extending into the submucosa and associated with erosions, with minimal to mild epithelial hyperplasia and minimal to mild mucin depletion from goblet cells; Score 3, mild to moderate inflammatory cell infiltrates that were sometimes transmural, often associated with ulceration, with moderate epithelial hyperplasia and mucin depletion; Score 4, marked inflammatory cell infiltrates that were often transmural and associated with ulceration, with marked epithelial hyperplasia and mucin depletion; Score 5, marked transmural inflammation with severe ulceration and loss of intestinal glands.

Statistical analysis

Means ± sd values are shown in all figures unless otherwise indicated. One-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test, was performed on datasets when comparing multiple groups simultaneously. One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test, was performed on datasets when comparing individual samples with a single control sample. Normalized datasets were compared using the repeated measures ANOVA, followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. Histopathological scores of colon sections were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Small molecules enhance the ability of TGF-β to induce functional Tregs

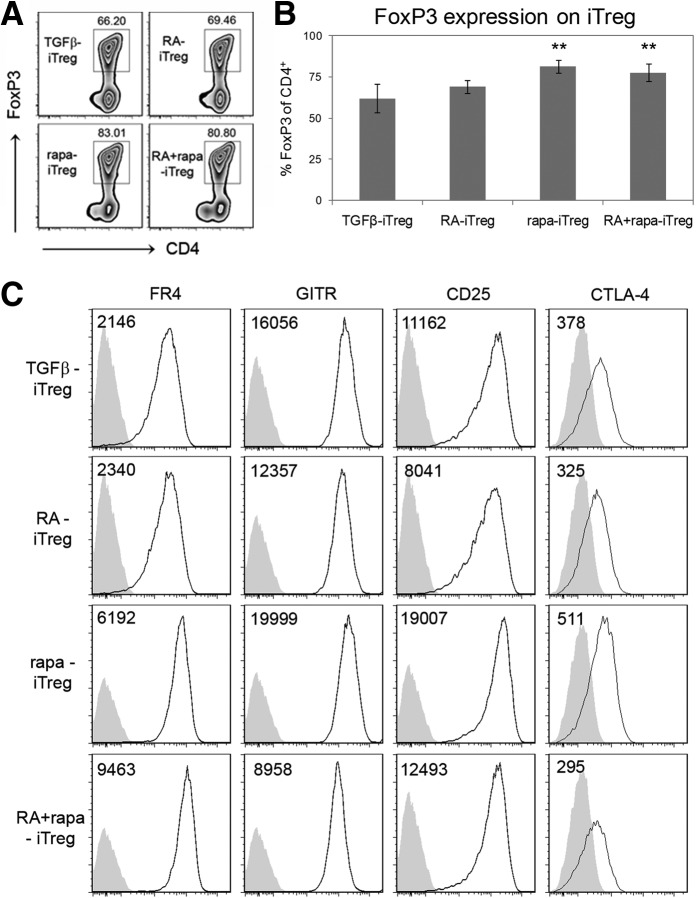

Tregs can be induced under a variety of in vitro [12, 14, 18, 19, 21] and in vivo conditions [22–24] to exhibit distinct characteristics that distinguish them from each other and from nTregs. Identification of these distinctive characteristics provides insight into their potential use in treating inflammatory disorders (such as autoimmune diseases and allergic hypersensitivity) and transplant rejection or in preventing tumor growth and metastasis [25]. In this study, in vitro-generated rapa-iTregs were compared directly with TGF-β-iTregs and RA-iTregs. Consistent with prior studies [12, 14, 18–20], we observed that the presence of RA or rapa enhanced the ability of IL-2 and TGF-β to induce FoxP3 expression in CD4+ CD25− naive T cells following activation (Fig. 1A and B and Supplemental Table 1). The same effect was observed when cells were cultured in the presence of a combination of IL-2, TGF-β, RA, and rapa. Cells cultured under all of these different conditions also expressed canonical Treg markers, such as FR4, CTLA4, GITR, and CD25 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that these cells were iTregs. Interestingly, the expression level of one of these markers, FR4 (which, along with CD25, can help distinguish activated Teff from Treg [26] and correlates with improved survival and stability), was notably greater in rapa-iTregs and RA + rapa-iTregs when compared with RA-iTregs (Supplemental Fig. 1). It has been suggested that expression of this FR may allow for greater survival and long-term stability of Treg populations in the periphery [26], and it remains to be determined if this is the case with rapa-iTregs and RA + rapa-iTregs. Additionally, we observed that these iTreg populations did not express or expressed similar levels of additional intracellular transcription factors (T-bet, GATA-3, etc.), used to classify Tregs based on their functional specialization (data not shown) [27–29]. A further notable observation was that addition of rapa lowered total cell yields (Supplemental Fig. 2A); however, only the combination of both small molecules together with cytokines led to a marked lowering of the total number of iTregs (FoxP3+ cells; Supplemental Fig. 2B).

Figure 1. RA and rapa enhance the ability of TGF-β to induce a Treg phenotype.

(A) Flow cytometry density plots indicating percent of CD4+ cells that express FoxP3 (representative of six independent experiments). Plots were generated after gating on CD4+ cells. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percent of CD4+ cells that express FoxP3. **P < 0.01 when the specified group was compared with the TGF-β-iTreg group using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Dunnett's test (based on n≥6). (C) Representative histograms (at least two independent experiments) for canonical markers expressed on Tregs. Plots were generated after gating on CD4+ FoxP3+ cells. Numbers on plots represent MFIs. Gray histograms represent isotype controls.

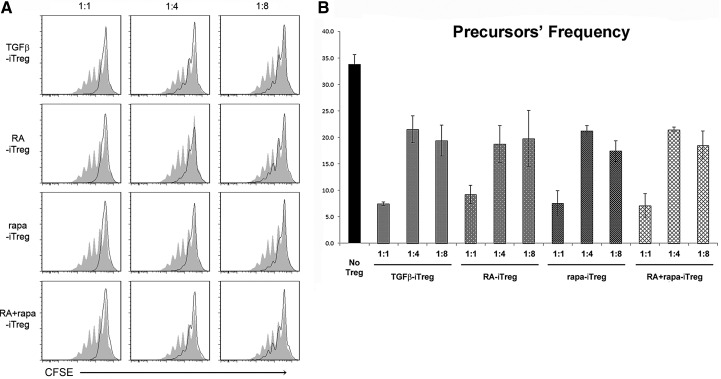

To determine the in vitro function of iTregs, their ability to suppress autologous, naive T cell proliferation in culture was tested. For this experiment, CFSE-stained CD4+ CD25− naive T cells, isolated from CD45.1 mice, were cocultured with iTregs (generated from CD45.2 mice) in the presence of αCD3/αCD28-labeled Dynal beads. We observed that the naive T cells were capable of robust proliferation when cultured in the absence of Tregs (Fig. 2A; gray background), but their proliferative capacity was decreased substantially when cultured in the presence of iTregs, generated under each of the conditions examined (Fig. 2). Quantitative analysis of the suppressive capacity of the different iTreg populations (based on estimation of stimulated T cell “precursor frequency”: the number of parent T cells induced to proliferate under each experimental condition to give rise to the observed CFSE dilution profile) revealed a similar in vitro-suppressive ability (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the proliferative capacity of naive T cells was restored in a similar manner among the groups, as the ratio of naive T cells:iTreg was increased.

Figure 2. iTregs suppress naive T cell proliferation.

Treg function determined using the CFSE dilution assay. (A) Filled histograms (gray) represent the proliferative capacity of naive T cells only (in the presence of stimulation). Numbers on top of the histograms indicate the ratio of Treg:naive T cells. Plots are representative of at least two independent experiments. (B) Quantitative analysis of the different iTreg groups from the experiment depicted in A. Precursor frequency corresponds to the frequency of T cells in the original seeded population that was stimulated to proliferate to give rise to the observed CFSE dilution profile (as calculated by ModFit LT). This number is inversely proportional to the extent of Treg-suppressive capacity. All iTreg populations exerted statistically significant suppression versus the no-iTreg group (P<0.05).

iTreg stability upon restimulation

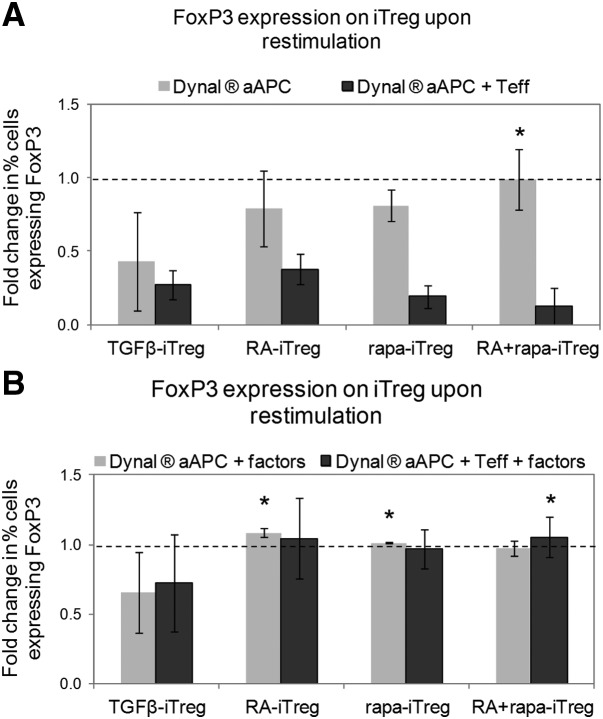

Various reports in the literature suggest that iTregs (tend to) lose their FoxP3 expression in the presence of high levels of antigenic stimulation and inflammatory cytokines (such as IFN-γ and IL-6) [30–32]. For example, it has been demonstrated that following long-term (>8 days) in vitro culture [9] or in the presence of inflammatory factors [10, 11], there is a considerable reduction in the incidence of FoxP3-expressing cells among the TGF-β-iTregs. To determine if the same were true of iTregs generated in the presence of RA and/or rapa, these induced populations were restimulated through TCR activation (αCD3/CD28 Dynal beads) with IL-2 (no addition of TGF-β, RA, or rapa) in the absence or presence of Teff (generated by activating CD4+ CD25− naive T cells from CD45.2 mice for 4 days in the presence of Dynal beads and 10 ng/ml IL-2). The rationale for using Teff in these in vitro cultures was to mimic the immune microenvironment that iTregs would likely encounter in inflamed tissues. Restimulation of TGF-β-iTregs in the absence of Teff led to a considerable reduction in the incidence of FoxP3+ cells (among the iTreg population) when compared with RA-iTregs, rapa-iTregs, and RA + rapa-iTregs. Furthermore, the presence of Teff led to a marked decrease in FoxP3-expressing cells among all of the iTreg groups (Fig. 3A). This loss of FoxP3 expression was limited to the presence of Teff; such an effect was not observed in the presence of mature DCs (data not shown). Additionally, the presence of IL-2 and TGF-β alone did not prevent the loss of FoxP3+ cells among the TGF-β-iTregs, which showed significantly lower percentages of FoxP3+ cells when compared with other iTregs (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, Treg-inducing factors (IL-2, TGF-β, and RA for RA-iTregs; IL-2, TGF-β, and rapa for rapa-iTregs; IL-2, TGF-β, RA, and rapa for RA+rapa-iTregs), during restimulation, prevented the decrease in incidence of FoxP3+ cells (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that the use of ex vivo-generated Tregs, induced in the presence of RA and/or rapa, might be limited to situations where a supportive milieu can be established in vivo, for example, using low-dose immunosuppressive regimens or controlled release formulations for immunomodulatory agents [33]. Furthermore, it has been suggested recently that the methylation patterns on the FoxP3 gene locus are a good determinant of long-term Treg stability [9]. It remains to be determined if these iTreg differ in this aspect.

Figure 3. iTregs generated in the presence of RA and/or rapa are more stable than TGF-β-iTregs in long-term cultures.

Quantitative analysis of the fold change in percent FoxP3+ iTregs (assessed by flow cytometry) after in vitro restimulation, in the absence (A) or presence (B) of Treg-inducing factors and in the absence (gray bars) or presence (black bars) of prestimulated Teff. Treg-inducing factors indicate the cytokines and/or small molecules used to generate the iTregs. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Fold change is expressed as the ratio between the percent of FoxP3+ cells at the end of the restimulation cultures to the percent of FoxP3+ cells at the beginning of the cultures. Dotted lines indicate normalized values of percent of FoxP3+ cells at the beginning of the cultures. *P < 0.05 when the specified group was compared with the TGF-β-iTreg group using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Dunnett's test.

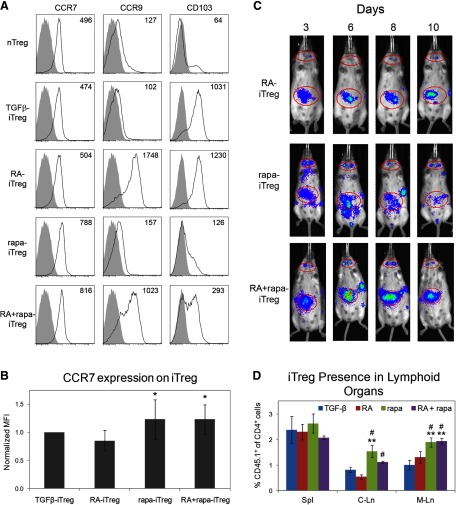

Expression of migratory receptors on iTregs and their in vivo homing capacity

RA-iTregs are known to express CCR9 and CD103 on their surface, which direct migration of cells toward the small intestine LP and possibly skin epithelium [12, 14]. These RA-iTregs are reported to have the potential to prevent inflammation in the gut. We observed that rapa-iTregs did not express either of these markers but expressed relatively higher levels of CCR7 (Fig. 4A and B) when compared with RA-iTregs. Interestingly, RA + rapa-iTregs, which also expressed significantly elevated levels of CCR7, appeared to comprise three distinct iTreg populations based on their expression of CCR9 and CD103, where 35.7% cells were CCR9+ CD103+, 33.2% cells were CCR9+ CD103−, and 22.1% cells were CCR9− CD103− (Supplemental Fig. 3). This heterogeneity could suggest that cells affected by RA are not influenced by rapa and vice versa (although the CCR9+CD103− population cannot be associated specifically with RA or rapa).

Figure 4. Differential expression of migratory receptors on iTregs, generated under different conditions, leads to distinct iTreg localization patterns in vivo following their adoptive transfer.

(A) Histograms depicting expression patterns of different migratory receptors, plotted after gating on CD4+ FoxP3+ cells. Numbers on plots represent MFI values. (B) Quantitative analysis of CCR7 expression on iTregs generated under different conditions (MFI values were normalized to TGF-β-iTregs). *P < 0.05 when comparing normalized data of a specified group with the RA-iTreg group using repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Tukey-Kramer test; n = 5. (C) Representative images acquired using the IVIS 200, showing in vivo iTreg localization over 10 days. Red ellipses indicate the cervical LN (small ellipse) and gut area (large ellipse). (D) iTregs generated from CD45.1+ mice were injected into CD45.2+ mice, and after 3 days, spleen (Spl), cervical LNs (C-Ln), and mesenteric LNs (M-Ln) harvested to analyze the percentage of CD45.1+ cells. **P < 0.01 when comparing the specified group with the TGF-β-iTreg group; #P < 0.05 when comparing data of the specified group with RA-iTregs using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey-Kramer test.

To determine if the differential expression of these receptors would affect in vivo homing, we explored the migration patterns of adoptively transferred iTregs over 10 days using intravital tracking experiments that permitted the study of cell movement in vivo in the same animals over time. Following adoptive transfer of luminescent iTregs, we observed that RA-iTregs and rapa-iTregs had divergent distribution patterns, with the former migrating in a diffuse pattern to the gut and skin tissue, whereas the latter migrated mainly to lymphoid tissues. This difference was evident within 3 days and persisted for over 10 days (Fig. 4C). Additionally, the data suggested that RA + rapa-iTregs migrated to the secondary lymphoid organs and the gut, although there were considerably greater numbers of cells in the gut tissue. In Fig. 4C, a high luminescence signal can be seen in the gut region of mice infused with rapa-iTregs. This most likely represents cells that have migrated to the mesenteric LNs (as the images obtained using the noninvasive imaging technique are two-dimensional, it is not possible to distinguish signals obtained from the mesenteric LNs and the rest of the gut). This finding was verified through adoptive transfer of iTregs generated from CD45.1 mice into congenic CD45.2 mice. Three days following adoptive transfer, significantly greater numbers of rapa-iTregs and RA + rapa-iTregs were observed in the cervical and mesenteric LNs when compared with TGF-β-iTregs and RA-iTregs (Fig. 4D). In addition, we observed that all adoptively transferred iTreg populations maintained their FoxP3 expression (Supplemental Fig. 4). The preferential accumulation of rapa-iTreg versus RA-iTregs in lymphoid tissues was evident, even in gut-associated tissues. Our analysis of the frequency of adoptively transferred iTregs between PP and LP, 6 days post-transfer, revealed a higher accumulation of rapa-iTregs in PP, with a negligible difference between the two populations at the level of LP (Supplemental Fig. 5). Overall, these data indicate that ex vivo Treg induction in the presence of rapa renders a population with the unique ability to accumulate in lymphoid organs, a characteristic that could be extremely valuable for prompt regulation of adverse immune responses developing in such tissues.

It is conceivable that these differences in migratory capacities observed between RA- and rapa-iTregs might result in different abilities to control local immune responses in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we determined the suppressive effect of RA- and rapa-iTregs in a T cell-mediated colitis model induced by the adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25− T cells into Rag2-KO mice, a modification of the original Powrie colitis model [34]. This is characterized by the development of a rapid wasting disease (Fig. 5A) [35]. To exclude any contribution of the differential rates of conversion into FoxP3+ cells (Fig. 1A), iTregs were generated from CD4+CD25− T cells isolated from FoxP3-EGFP mice and the induced EGFP+ cells purified by FACS before transfer. Coinjection of FACS-purified RA- or rapa-iTregs with T cells at a 1:1 ratio caused the complete prevention of weight loss (data not shown). However, when a lower proportion of iTregs (1:4) was used, we observed a superior ability of rapa-iTregs to delay disease progression (Fig. 5A). Histological analysis of colon specimens collected from recipient mice, 8 days postadoptive transfer, confirmed the difference in protective ability between RA- and rapa-iTregs (Fig. 5B and C). In fact, histological scoring of different groups showed a significant difference between the No-Treg and rapa-iTreg groups, whereas no significant difference was observed with animals cotransferred with RA-iTregs (Fig. 5B). Colon sections from mice coinjected with CD4+CD25− T cells plus rapa-iTregs showed limited inflammatory cell infiltrates, with minimal epithelial hyperplasia and mild mucin depletion from goblet cells. In contrast, mice coinjected with RA-iTregs showed high levels of mucosal hypertrophy, pronounced cell infiltration of the LP, and distortion of the crypts that differed minimally from animals that received CD4+CD25− T cells only (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these data suggest that although RA- and rapa-iTregs are powerful regulators of immune reactivity, their divergent in vivo distribution pattern confers upon them a different capacity to modulate pathological immune responses, depending on the disease-development stage and the tissue affected. Additionally, it is of notice that RA + rapa-iTregs expressed overall higher levels of CCR7, while also containing cell populations that expressed CCR9 and CD103. We intend to investigate if such an expression pattern allows the RA + rapa-iTregs to be more efficient at suppressing immune responses in vivo (as a result of their ability to migrate simultaneously to different organs in vivo) and if such an effect can or cannot be reproduced using a mixture of RA-iTregs and rapa-iTregs.

Figure 5. RA- and rapa-iTregs exhibit different in vivo abilities to control colitogenic T cells that correlate with their differential distribution pattern.

To evaluate the suppressive capacity of RA- and rapa-iTregs in an in vivo inflammatory context, 1 × 106 CD4+CD25− T cells were injected i.v. into Rag2-KO mice without (No Treg; blue line) or with 2.5 × 105 of RA-iTreg (red line) or rapa-iTreg (green line) and the change in body weight monitored every 2 days; n = 4 mice/group. (B) A second set of Rag2-KO mice (n=9/group) received the same T cell combinations indicated in A, and on Day-8 postadoptive transfer, their colons were isolated and sectioned and histopathological scores obtained for the different groups. Differences among groups were determined using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (*P<0.02). (C) Representative sets of H&E-stained colonic sections obtained from the indicated groups.

Based on our results, we argue that to optimize a therapeutic protocol based on adoptive transfer of iTregs, it will be necessary to consider the ideal site of activity of the cells to be administered and to tailor their induction or expansion to favor their accumulation to that specific tissue. This concept has been investigated elegantly by Issa et al. [36], who showed in a humanized mouse model of human skin transplantation that different populations of human Tregs display distinct efficacy in vivo based on their expression of tissue-specific homing molecules. In this regard, it will be important to demonstrate that our findings extend to human iTregs. Although some differences have been outlined in the past between the suppressive capacities of mouse and human iTregs, induced with TGF-β only [37], recent investigations have demonstrated the importance of adding RA or rapa during the conversion to generate stable and powerful suppressors. These are the same reagents that we have considered in our investigation, and we are in the process of investigating their impact on migration of human iTregs.

Finally, given the challenges and cost associated with cellular therapies, a system capable of inducing Tregs in vivo would be suited ideally to treating autoimmune disease and transplant rejection. To this end, formulations would be necessary that deliver a combination of Treg-inducing factors in a local and sustained manner, as can be achieved using controlled release formulations [38]. The preferred combination of factors to be used in vivo might be IL-2, TGF-β, and rapa, as rapa (1) is currently approved for clinical use, (2) has the ability to suppress a variety of immune functions apart from inducing Tregs, and (3) might be safer than RA, given the latter's ability to induce hypervitaminosis A.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication was made possible by grant KL2 RR024154 (to S.R.L.) from the National Center for Research Resources (a component of the U.S. National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research). This work was also supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI67541 (to A.W.T.) and by the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation (to S.R.L.). G.R. is in receipt of an American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award (1-10-JF-43) and the STI Joseph Patrick Fellowship. L.C.C. is supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute predoctoral fellowship.

We thank STI and Department of Immunology Flow Cores for their assistance with all of the flow cytometry-based experiments. We also thank the STI Histology Core for assistance with preparation of colon sections. We are grateful to Drs. Adriana Larregina and Adrian Morelli for their support with histological analysis and scoring.

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

- aAPC

- artificial APC

- FoxP3

- forkhead box P3

- FR

- folate receptor

- GITR

- glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related

- iTreg

- induced regulatory T cell

- KO

- knockout

- LP

- lamina propria

- MFI

- median fluorescence intensity

- nTreg

- natural regulatory T cell

- PP

- Peyer's patches

- RA

- retinoic acid

- rapa

- rapamycin

- STI

- Starzl Transplantation Institute

- Teff

- effector T cell

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

AUTHORSHIP

S.J., G.R., A.W.T. and S.R.L. conceived of the idea, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. S.J. performed all of the experiments, and G.R. assisted with all of the experiments. L.C.C. helped with the in vivo migratory experiments and performed all of the in vivo suppression experiments. E.E.N. helped with the in vitro Treg induction experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wieckiewicz J., Goto R., Wood K. J. (2010) T regulatory cells and the control of alloimmunity: from characterisation to clinical application. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 22, 662–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Riley J. L., June C. H., Blazar B. R. (2009) Human T regulatory cell therapy: take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity 30, 656–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brusko T. M., Putnam A. L., Bluestone J. A. (2008) Human regulatory T cells: role in autoimmune disease and therapeutic opportunities. Immunol. Rev. 223, 371–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trzonkowski P., Bieniaszewska M., Juscinska J., Dobyszuk A., Krzystyniak A., Marek N., Myskiwska J., Hellmann A. (2009) First-in-man clinical results of the treatment of patients with graft versus host disease with human ex vivo expanded CD4+CD25+CD127− T regulatory cells. Clin. Immunol. 133, 22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brunstein C. G., Miller J. S., Cao Q., McKenna D. H., Hippen K. L., Curtsinger J., DeFor T., Levine B. L., June C. H., Rubinstein P., McGlave P. B., Blazar B. R., Wagner J. E. (2011) Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics. Blood 117, 1061–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Safinia N., Sagoo P., Lechler R., Lombardi G. (2010) Adoptive regulatory T cell therapy: challenges in clinical transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 15, 427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fu S., Zhang N., Yopp A. C., Chen D., Mao M., Zhang H., Ding Y., Bromberg J. S. (2004) TGF-β induces FoxP3 + T-regulatory cells from CD4+ CD25− precursors. Am. J. Transplant. 4, 1614–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen W., Jin W., Hardegen N., Lei K. J., Li L., Marinos N., McGrady G., Wahl S. M. (2003) Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-β induction of transcription factor FoxP3. J. Exp. Med. 198, 1875–1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Floess S., Freyer J., Siewert C., Baron U., Olek S., Polansky J., Schlawe K., Chang H. D., Bopp T., Schmitt E., Klein-Hessling S., Serfling E., Hamann A., Huehn J. (2007) Epigenetic control of the FoxP3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 5, e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Veldhoen M., Hocking R. J., Atkins C. J., Locksley R. M., Stockinger B. (2006) TGF-β in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity 24, 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bettelli E., Carrier Y., Gao W., Korn T., Strom T. B., Oukka M., Weiner H. L., Kuchroo V. K. (2006) Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mucida D., Park Y., Kim G., Turovskaya O., Scott I., Kronenberg M., Cheroutre H. (2007) Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science 317, 256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lu L., Zhou X., Wang J., Zheng S. G., Horwitz D. A. (2011) Characterization of protective human CD4+CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells generated with IL-2, TGF-β and retinoic acid. PLoS One 5, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Benson M. J., Pino-Lagos K., Rosemblatt M., Noelle R. J. (2007) All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1765–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DePaolo R. W., Abadie V., Tang F., Fehlner-Peach H., Hall J. A., Wang W., Marietta E. V., Kasarda D. D., Waldmann T. A., Murray J. A., Semrad C., Kupfer S. S., Belkaid Y., Guandalini S., Jabri B. (2011) Co-adjuvant effects of retinoic acid and IL-15 induce inflammatory immunity to dietary antigens. Nature 471, 220–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones D. H. (1989) The role and mechanism of action of 13-cis-retinoic acid in the treatment of severe (nodulocystic) acne. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 91–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barua A. B., Olson J. A. (1996) Percutaneous absorption, excretion and metabolism of all-trans-retinoyl beta-glucuronide and of all-trans-retinoic acid in the rat. Skin Pharmacol. 9, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kopf H., de la Rosa G. M., Howard O. M. Z., Chen X. (2007) Rapamycin inhibits differentiation of Th17 cells and promotes generation of FoxP3+ T regulatory cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 7, 1819–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haxhinasto S., Mathis D., Benoist C. (2008) The AKT-mTOR axis regulates de novo differentiation of CD4 +FoxP3+ cells. J. Exp. Med. 205, 565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cobbold S. P., Adams E., Farquhar C. A., Nolan K. F., Howie D., Lui K. O., Fairchild P. J., Mellor A. L., Ron D., Waldmann H. (2009) Infectious tolerance via the consumption of essential amino acids and mTOR signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12055–12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hill J. A., Hall J. A., Sun C. M., Cai Q., Ghyselinck N., Chambon P., Belkaid Y., Mathis D., Benoist C. (2008) Retinoic acid enhances FoxP3 induction indirectly by relieving inhibition from CD4+CD44hi cells. Immunity 29, 758–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mucida D., Kutchukhidze N., Erazo A., Russo M., Lafaille J. J., Curotto De Lafaille M. A. (2005) Oral tolerance in the absence of naturally occurring Tregs. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1923–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu V. C., Wong L. Y., Jang T., Shah A. H., Park I., Yang X., Zhang Q., Lonning S., Teicher B. A., Lee C. (2007) Tumor evasion of the immune system by converting CD4+CD25− T cells into CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells: role of tumor-derived TGF-β. J. Immunol. 178, 2883–2892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cobbold S. P., Castejon R., Adams E., Zelenika D., Graca L., Humm S., Waldmann H. (2004) Induction of foxP3+ regulatory T cells in the periphery of T cell receptor transgenic mice tolerized to transplants. J. Immunol. 172, 6003–6010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Campbell D. J., Koch M. A. (2011) Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 119–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamaguchi T., Hirota K., Nagahama K., Ohkawa K., Takahashi T., Nomura T., Sakaguchi S. (2007) Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity 27, 145–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barnes M. J., Powrie F. (2009) Hybrid Treg cells: steel frames and plastic exteriors. Nat. Immunol. 10, 563–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koch M. A., Tucker-Heard G., Perdue N. R., Killebrew J. R., Urdahl K. B., Campbell D. J. (2009) The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 10, 595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zheng Y., Chaudhry A., Kas A., deRoos P., Kim J. M., Chu T. T., Corcoran L., Treuting P., Klein U., Rudensky A. Y. (2009) Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature 458, 351–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murphy K. M., Stockinger B. (2010) Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat. Immunol. 11, 674–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou X., Bailey-Bucktrout S. L., Jeker L. T., Penaranda C., Martinez-Llordella M., Ashby M., Nakayama M., Rosenthal W., Bluestone J. A. (2009) Instability of the transcription factor FoxP3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1000–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee Y. K., Mukasa R., Hatton R. D., Weaver C. T. (2009) Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21, 274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jhunjhunwala S., Raimondi G., Thomson A. W., Little S. R. (2009) Delivery of rapamycin to dendritic cells using degradable microparticles. J. Control Rel. 133, 191–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asseman C., Mauze S., Leach M. W., Coffman R. L., Powrie F. (1999) An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 190, 995–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Housley W. J., Adams C. O., Nichols F. C., Puddington L., Lingenheld E. G., Zhu L., Rajan T. V., Clark R. B. (2011) Natural but not inducible regulatory T cells require TNF-α signaling for in vivo function. J. Immunol. 186, 6779–6787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Issa F., Hester J., Milward K., Wood K. J. (2012) Homing of regulatory T cells to human skin is important for the prevention of alloimmune-mediated pathology in an in vivo cellular therapy model. PLoS One 7, e53331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lan Q., Fan H., Quesniaux V., Ryffel B., Liu Z., Zheng S. G. (2012) Induced FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells: a potential new weapon to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases? J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 22–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jhunjhunwala S., Balmert S. C., Raimondi G., Dons E., Nichols E. E., Thomson A. W., Little S. R. (2012) Controlled release formulations of IL-2, TGF-β1 and rapamycin for the induction of regulatory T cells. J. Control Release 159, 78–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.