ILC2s express arginase-I independently of STAT6 in resting tissue and during helminth infection.

Keywords: ILC2, Yarg, Arg1-YFP, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, alternatively activated macrophages

Abstract

Arg1 is produced by AAMs and is proposed to have a regulatory role during asthma and allergic inflammation. Here, we use an Arg1 reporter mouse to identify additional cellular sources of the enzyme in the lung. We demonstrate that ILC2s express Arg1 at rest and during infection with the migratory helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. In contrast to AAMs, which express Arg1 following IL-4/IL-13-mediated STAT6 activation, ILC2s constitutively express the enzyme in a STAT6-independent manner. Although ILC2s deficient in the IL-33R subunit T1/ST2 maintain Arg1 expression, IL-33 can regulate total lung Arg1 by expanding the ILC2 population and by activating macrophages indirectly via STAT6. Finally, we find that ILC2 Arg1 does not mediate ILC2 accumulation, ILC2 production of IL-5 and IL-13, or collagen production during N. brasiliensis infection. Thus, ILC2s are a novel source of Arg1 in resting tissue and during allergic inflammation.

Introduction

Arg1 is a urea cycle enzyme that hydrolyzes L-arginine into L-ornithine and urea [1]. First identified in the mammalian liver, Arg1 is also highly induced during type 2 inflammation caused by allergens or parasites. Elevated Arg1 expression in lung tissue is observed in asthma models induced by sensitization with OVA or Aspergillus fumigatus, as well as during helminth infection with N. brasiliensis larvae and Schistosoma mansoni eggs [2–4]. Although Arg1 has been shown to suppress S. mansoni-induced fibrosis in the liver [5], the functions of this enzyme in the lung during type 2 responses have been elusive [6].

Previous studies have demonstrated that macrophages activated by type 2 cytokines produce Arg1 during inflammation [7–9]. Macrophages stimulated in this manner express a distinct set of genes in addition to Arg1, including Chi3l3/Ym1, Retnla/Fizz1, and Mrc1/MMR, and are designated alternatively activated in contrast to macrophages classically activated by IFN-γ [10–12]. Components of the IL-4/IL-13 signaling pathway required for alternative activation include IL-4Rα, which complexes with the common γ-chain or IL-13Rα1 to form the IL-4R and IL-13R, respectively [9], and STAT6, which is phosphorylated by IL-4R- and IL-13R-associated kinases and activates Arg1 gene expression [13, 14]. Although macrophages constitute a significant source of Arg1 during type 2 inflammation, additional cellular sources of this enzyme have not been defined.

ILC2s are recently discovered cells that accumulate in tissue during type 2 inflammation, where they are important sources of IL-5 and IL-13 [15–17]. ILC2s are characterized as Lin− cells that express IL-7Rα and T1/ST2, a component of the IL-33R [15, 17]. Exogenous IL-33 increases ILC2 numbers, and T1/ST2-deficient mice have reduced ILC2s during inflammation, suggesting that IL-33 is critical for the expansion of this population [16, 17]. The epithelial cytokines TSLP and IL-25 have additionally been shown to be important in ILC2 responses [17, 18]. Further understanding of ILC2 signaling and activation is needed to identify other functions of these cells during homeostasis and inflammation.

In this study, we characterize leukocyte populations that express Arg1 in the lung at rest and during infection with the helminth N. brasiliensis. We show that ILC2s are a previously undescribed source of Arg1 in the lung and that these cells express Arg1 independently of STAT6. We determine that IL-33 can regulate arginase activity in the lung by increasing ILC2 numbers and by activating macrophages indirectly through cytokine-mediated STAT6 activation. Thus, Arg1 is regulated by STAT6-dependent and -independent pathways in discrete hematopoietic populations during type 2 inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Arg1-YFP (Yarg) mice were described previously [19]. Red5 mice contain a RFP-IRES-Cre recombinase construct that replaces the endogenous IL5 gene, as described [20]. STAT6-deficient mice and Arg1-flox mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) [21, 22]. T1/ST2-deficient mice (a generous gift from Martin Steinhoff, UCSF, CA, USA) have been described [23]. All mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6 for at least 10 generations. Studies were conducted in accordance with the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue dissociation

Lungs were perfused with 10 ml PBS, removed, minced, and pressed through a 70-μm nylon mesh to obtain a single-cell suspension. Small intestines were digested in 0.1 Wünsch/ml Liberase TM (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for four cycles of 20 min incubations and filtered through 70-μm nylon mesh. Hematopoietic intestinal cells were enriched by Percoll density gradient separation.

Flow cytometry

Rat anti-mouse CD3 (17A2), rat anti-mouse IL-7Rα (A7R34), rat anti-mouse F4/80 (BM8), rat anti-mouse Ly6G (RB6-8C5), mouse anti-mouse NK1.1 (PK136), rat anti-mouse MHC class II (M5/114.15.2), and rat anti-mouse IL-13Rα1 (13MOKA) antibodies and streptavidin APCs were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA); rat anti-mouse CD11b (M1/70), Armenian hamster anti-mouse CD11c (HL3), rat anti-mouse CD132 (FCM), and rat anti-mouse Siglec-F (E50-2440) antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Jose, CA, USA); rat anti-mouse B220 (RA3-6B2), rat anti-mouse CD25 (PC61), Syrian hamster anti-mouse KLRG1 (2F1/KLRg1), and Armenian hamster anti-mouse ICOS (C398.4A) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA); and rat anti-mouse T1/ST2 (DJ8) antibodies were purchased from MD Bioproducts (St. Paul, MN, USA).

Antibody-stained samples were incubated with DAPI, and live cells were selected by gating on DAPI− cells that had a cellular FSC/SSC profile. To gate on YFP+ macrophages, an open channel was used (PE, PerCP-cy5.5, or AmCyan) to account for autofluorescence. Cell surface marker expression on macrophages, with the exception of Siglec-F, was determined using APC-conjugated antibodies, as macrophage autofluorescence was minimal in the APC channel. Autofluorescence histograms were determined by comparing macrophages with lymphocytes in the PerCP-cy5.5 channel. Cell counts were calculated using CountBright absolute counting beads (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). Flow cytometry experiments were done using a LSR II with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

N. brasiliensis infection

Mice were infected with N. brasiliensis, as described [24]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and injected with 500 third-stage larvae s.c. in 200 μl saline. Mice were kept on antibiotic water (2 g/l neomycin sulfate, 100 mg/l Polymixin B) for the first 5 dpi. Worm burden was assessed in the small intestine by incubating filleted tissue in 10 ml HBSS for 2 h and counting worms under a dissecting microscope.

IL-33 treatment

Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and given 500 ng rIL-33 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in 20 μl PBS i.n. for 3 consecutive days. On the 4th day, whole lungs were isolated for flow cytometry.

Measurement of ILC2 cytokine production

Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+ ILC2s (1×104) were sorted from infected lungs using a MoFlo XDP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and cells were incubated in 100 μl complete RPMI at 37°C. After 8 h, supernatants were assayed for IL-9 and IL-13 by cytokine bead array (BD Biosciences).

Measurement of acid- and pepsin-soluble collagen

The superior lobes of infected mouse lungs were minced finely and incubated with 0.1 mg/ml pepsin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.5 M acetic acid overnight. Supernatants were neutralized and labeled with Sircol dye (Biocolor, County Antrim, UK).

Arginase enzyme activity assay

Eosinophils, ILC2s, and macrophages were sorted from C57BL/6 mice, and arginase enzyme activity was determined using a modified version of published methods [25]. Cells (2.5×104) from each population were lysed in 50 μl 0.1% Triton X-100 containing protease inhibitors (Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail, EDTA-free; Roche Applied Science) and incubated with 50 μl 10 mM MnCl 4H2O, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, for 10 min at 55°C to activate arginase. Aliquots (50 μl) were transferred to two Eppendorf tubes and mixed with 50 μl 0.5 M arginine, pH 9.7 (Sigma). Samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and then stopped with 400 μl of a 1:3:7 acid mixture of H2SO4, H3PO4, and H2O, or were stopped immediately to establish urea levels in unreacted samples. 12.5 μl of 9% α-isonitrosopropiophenone (Sigma) dissolved in ethanol was added to stopped samples and incubated at 95°C. ODs were read at 540 nm with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and arginase enzyme activity was determined by subtracting the amount of urea detected in unreacted samples from the urea detected after the 2-h reaction.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using the two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Arg1 is expressed by ILC2s and AAMs in the lung during N. brasiliensis infection

To characterize hematopoietic populations that express Arg1, we generated Arg1-YFP reporter mice, in which IRES-enhanced YFP was inserted in Exon 8, downstream of the endogenous stop codon and upstream of the 3′ untranslated region [19]. This insertion does not disrupt Arg1 expression, as determined by enzyme assays conducted on tissue isolated from homozygous mice (data not shown). To induce type 2 inflammation, Arg1-YFP mice were infected s.c. with N. brasiliensis, which migrates through the lung within the first few days of infection [26]. Worms translocate to the intestine by Day 3, but lung inflammation continues to intensify through 9–10 dpi [24].

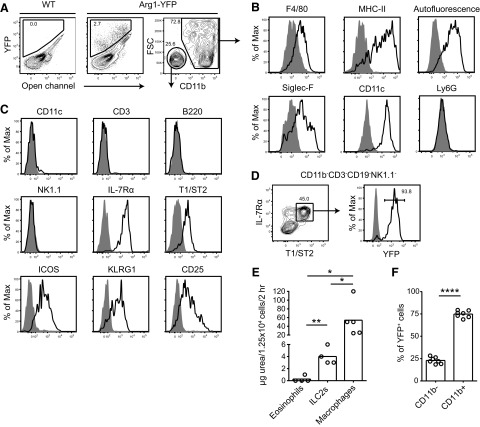

On Day 9, two major YFP+ populations were detected in the lung, which could be distinguished on the basis of CD11b expression (Fig. 1A). YFP+CD11b+ cells were macrophages based on expression of F4/80, MHC class II, and high autofluorescence (Fig. 1B). These cells were also CD11c+ and Siglec-F+, consistent with their identification as alveolar macrophages. In contrast, the YFP+CD11b− population lacked autofluorescence, as well as the myeloid and lymphoid Lin markers CD11c, CD3, B220, and NK1.1 (Fig. 1C, and data not shown). We identified these Lin− cells as ILC2s based on their expression of IL-7Rα, T1/ST2, ICOS, KLRG1, and CD25. Over 90% of all T1/ST2+ ILC2s expressed YFP, making Arg1 an unexpected marker of ILC2s in the inflamed lung (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Arg1 is expressed by ILC2s and AAMs in the lung during N. brasiliensis infection.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of YFP expression at Day 9 of N. brasiliensis infection in Arg1-YFP mouse lungs. A WT control was used to set gates (left plot), and an open channel was used to identify autofluorescence. CD11b expression in YFP+ cells is shown in the right plot. (B) Characterization of cell surface markers expressed by YFP+CD11b+ cells by flow cytometry. Shaded histograms represent isotype controls, except in the histogram depicting autofluorescence, where the shaded plot represents autofluorescence in lymphocytes. (C) Cell surface markers expressed by YFP+CD11b− cells determined by flow cytometry. Shaded histograms are isotype controls. (D) Expression of YFP in Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+ ILC2s. Cells were previously gated on live CD11b−CD3−CD19−NK1.1− cells. The shaded histogram is from a WT control. (E) Arginase enzyme assay in sorted lung populations from infected C57BL/6 mice. Cells (1.25×104) of each population were sorted from Day 12-infected lungs, lysed, and assayed for urea production in a 2-h reaction in the presence of arginine. Data are representative of two independent experiments; n = 4–5/group, with each symbol representing a sort from an individual animal. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01. (F) Percent of YFP+ cells that are CD11b− (ILC2s) or CD11b+ (macrophages); n = 7, pooled from two independent experiments. ****P ≤ 0.0001.

To verify that ILC2s express arginase in WT mice, an enzyme assay was conducted to quantify urea production in lysates of cells sorted from the lungs of infected C57BL/6 mice. Arginase enzyme activity was detected in ILC2 (Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+) and macrophage (CD11b+autofluorescenthi) but not eosinophil cell lysates, validating our findings with the reporter mouse (Fig. 1E). Based on enzyme activity, macrophages produced over tenfold more arginase/cell than ILC2s. Arg1+ macrophages were also more abundant than ILC2s, which comprised ∼25% of all Arg1+ cells (Fig. 1F).

To determine whether ILC2s shared other markers expressed by alternative-activated macrophages, cells were assessed for expression of MMR, Retnla/FIZZ1, and Chi3l3/Ym1. ILC2s did not express MMR, as assessed by flow cytometry, or Retnla mRNA, as determined by quantitative PCR (Supplemental Fig. 1A and B). Chi3l3 mRNA was detected in ILC2s and not in B cells, although expression levels of Chi3l3 by ILC2s were low compared with AAMs; the difference in Chi3l3 expression between AAMs and ILC2s was 48-fold compared with the sixfold difference in Arg1 expression between the two populations. Thus, ILC2s express Arg1 without activating other components of the traditional transcriptional program associated with alternative activation in macrophages, with the possible exception of Chi3l3.

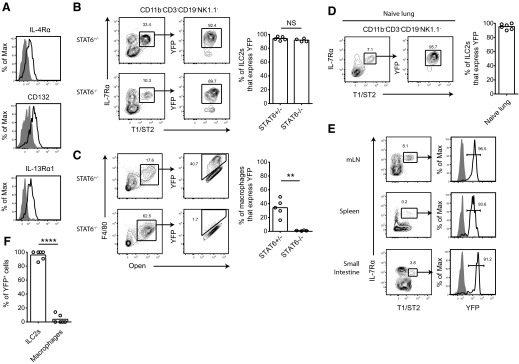

ILC2s constitutively express Arg1

The IL-4/IL-13/STAT6 signaling pathway induces alternatively activated genes, including Arg1, in macrophages [7–9, 13, 14]. As lung ILC2s express the receptor subunits IL-4Rα, CD132 (common γ-chain), and IL-13Rα1, these cells have the potential to respond to IL-4 and IL-13 (Fig. 2A). We investigated whether Arg1 expression by ILC2s was induced by IL-4/IL-13/STAT6 signaling by crossing Arg1 reporter mice with STAT6-deficient mice. Interestingly, Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+ lung ILC2s isolated from STAT6-deficient mice at 10 dpi maintained Arg1 expression (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the percentage of F4/80+ autofluorescent macrophages that expressed Arg1 was reduced by >30-fold in infected STAT6 knockout mice (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. ILC2s constitutively express Arg1.

(A) Expression of receptor subunits for type I and type II IL-4R in Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+ ILC2s by flow cytometry. Mice were infected with N. brasiliensis, and lung cells were stained on Day 9. Shaded histograms represent isotype controls. (B) YFP expression in lung ILC2s and (C) macrophages in STAT6-deficient mice. Cells were obtained from N. brasiliensis-infected lungs on Day 9. Flow cytometry plots on the left show the gating scheme used to obtain percentages graphed in the right panel. ILC2 plots were gated previously on live CD11b−CD3−CD19−NK1.1− cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments; n = 4–5. **P ≤ 0.01. (D) YFP expression in ILC2s isolated from the lungs of naive mice. Plots were gated previously on live CD11b−CD3−CD19−NK1.1− cells; n = 6, pooled from two independent experiments. (E) YFP expression in Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+ cells from the mesenteric LNs (mLN), spleen, and small intestine of naive mice. Plots were gated previously on CD11b−CD3−CD19−NK1.1− cells for the mesenteric LNs, and CD11b−CD3−CD5−CD19−NK1.1− cells for the spleen and small intestine. (F) Percent of YFP+ cells that are ILC2s or macrophages in the naive lung; n = 6, pooled from two independent experiments. ****P ≤ 0.0001.

As Arg1 expression in ILC2s was not induced by STAT6 signaling, we investigated whether naive ILC2s expressed the enzyme at rest. Indeed, >90% of ILC2s isolated from the naive lung, mesenteric LNs, spleen, and small intestine expressed Arg1, indicating that ILC2s express the enzyme constitutively (Fig. 2D and E). In the uninfected lung, ILC2s comprised >90% of all Arg1+ cells (Fig. 2F), making this population the primary hematopoietic cell source of Arg1 in the resting lung.

Arg1 deficiency does not affect ILC2 numbers or cytokine production

We next investigated whether Arg1 expression is required for ILC2 accumulation or function. Arg1 deficiency in mice is fatal 2 weeks after birth as a result of loss of the enzyme in hepatic cells [27]. To circumvent this issue, Arg1-flox mice have been generated to facilitate deletion of the enzyme in specific cell types of interest [22]. To target Arg1 deletion to ILC2s, we used Red5 mice, in which the IL-5 locus is disrupted by a construct containing RFP-IRES-Cre recombinase [20]. In these mice, ILC2s, but not macrophages, express RFP and Cre in N. brasiliensis-infected lungs as detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). We crossed Red5 mice with Arg1-flox mice to generate Red5-Arg1flox/flox mice, in which cells expressing IL-5 activate the recombinase and delete the Arg1 gene. Red5-Arg1flox/flox mice were healthy and had no obvious abnormalities (data not shown).

Figure 3. Arg1 deficiency does not affect ILC2 numbers or cytokine production.

(A) RFP expression in ILC2s (upper) or macrophages (lower) in Red5 lungs on Day 10 of N. brasiliensis infection. The shaded histograms represent WT controls. Plots for ILC2s were gated previously on live CD11b−CD3−CD19−NK1.1− cells. (B) RFP expression in ILC2s from Red5-Arg1flox/flox lungs at Day 10 of infection. The shaded histogram represents a WT control. Plots were gated previously on live CD11b−CD3−CD19−NK1.1− cells. (C) Arginase enzyme assay on ILC2s sorted from Red5-Arg1flox/flox lungs. Lin−IL-7Rα+T1/ST2+ cells (1.25×104) or CD4+ T cells were sorted from lungs at Day 10 of N. brasiliensis infection, lysed, and assayed for urea production after a 2-h reaction in the presence of arginine; n = 6; pooled from two independent experiments, with each n as a sort from an individual mouse. ***P ≤ 0.001. (D) Worm burden in Red5-Arg1flox/flox, Red5-Arg1flox/+, and Rag2-deficient positive controls at Day 10 of infection. Data are representative of two independent experiments; n = 4–5. (E) Total lung RFP+ ILC2 counts in Red5-Arg1flox/flox mice compared with Red5-Arg1flox/+ controls at Day 10 of infection. Data are representative of three independent experiments; n = 5–6. (F) IL-13 detected in the supernatants of unstimulated cultures of ILC2s, which were sorted from Day 10-infected mouse lungs and incubated in complete RPMI for 8 h. Data are representative of two independent experiments; n = 5. (G) Assessment of uncross linked collagen in Red5-Arg1flox/flox mice at Day 10 of infection. Acid- and pepsin-soluble collagen was extracted from the right superior lobe of the lung. Data are representative of two independent experiments; n = 5–6.

In N. brasiliensis-infected Red5-Arg1flox/flox mice, the percentage of the ILC2 population that expressed RFP was similar to that seen in Red5 mice, indicating that there was no selective growth advantage in rare, Red5-negative cells (Fig. 3B). ILC2 lysates from these mice were deficient in arginase activity, as assayed by urea production, indicating successful deletion of the Arg1 gene (Fig. 3C). The lack of enzyme activity in Arg1-deficient ILC2s also demonstrated that mitochondrial Arg2 does not compensate for the absence of Arg1 in these cells.

Red5-Arg1flox/flox mice cleared worms normally by Day 10 of infection (Fig. 3D). At this time-point, equivalent numbers of IL-5-producing ILC2s were present in infected Red5-Arg1flox/flox lungs compared with Red5-Arg1flox/+ controls, based on RFP+ cell counts (Fig. 3E). The mean fluorescence intensity of RFP also was unchanged by Arg1 deficiency (Fig. 3A and B, and data not shown). To assay other cytokines, ILC2s were sorted from infected lungs and cultured without stimulation. After 8 h, supernatants from Arg1-deficient and -sufficient ILC2 cultures contained equivalent amounts of IL-13, whereas IL-9 was undetectable in all cultures (Fig. 3F, and data not shown). Thus, Arg1 does not influence the accumulation of cytokine-producing ILC2s in the lung during worm infection.

To assay collagen production, infected lungs were digested overnight with pepsin and acetic acid to solubilize uncross linked collagen. There was no difference in the amounts of acid- and pepsin-soluble collagen extracted from Red5-Arg1flox/flox lungs and Red5-Arg1flox/+ controls, indicating that loss of ILC2-derived Arg1 does not affect collagen production during N. brasiliensis infection (Fig. 3G).

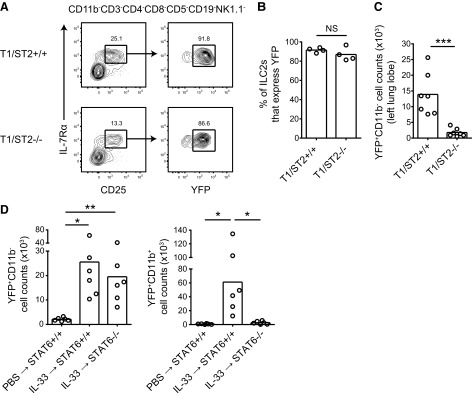

IL-33 can regulate Arg1+ cell numbers in lung tissue

IL-33, a member of the IL-1 superfamily of cytokines, has been implicated in the activation and expansion of ILC2s [15–17]. We reasoned that IL-33 could alter Arg1 expression in the lung by regulating ILC2 cell numbers. We first investigated whether Arg1 expression in ILC2s was affected by IL-33R deficiency using T1/ST2-deficient mice. This deficiency precludes the use of T1/ST2 as a marker of ILC2, so this population was identified as Lin−IL-7Rα+CD25+ (Fig. 4A). Based on these markers, ILC2s continue to express Arg1 in the absence of IL-33R (Fig. 4A and B), providing additional evidence for constitutive expression of this enzyme. As expected, there were significantly fewer CD11b− Arg1+ cells (ILC2s) in T1/ST2-deficient lungs compared with WT controls on Day 9 of infection (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. IL-33 can regulate Arg1+ cell numbers in lung tissue.

(A) Identification of ILC2s in T1/ST2-deficient mouse lungs using IL-7Rα and CD25. Cells are from Day 9 of N. brasiliensis infection. (B) Percent of lung ILC2s that express YFP in T1/ST2-deficient mice during inflammation. Cells were isolated from the left lung lobe at Day 9 of N. brasiliensis infection; n = 4. (C) Total lung YFP+CD11b− (ILC2) cell counts from infected, T1/ST2-deficient mice. Cell counts are from the left lung lobe at Day 9 of N. brasiliensis infection. Data are pooled from two independent experiments; n = 7. ***P ≤ 0.001. (D) Total lung YFP+CD11b− (ILC2) and YFP+CD11b+ (AAM) cell counts after administration of intranasal IL-33 in STAT6-deficient and -sufficient mice. rIL-33 (500 ng) was administered daily for 3 days, and cell counts in the whole lung were determined on Day 4; n = 6 and are the pooled data from two independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

To test whether IL-33 is sufficient to increase Arg1 expression in the lung by expanding ILC2s, rIL-33 was administered to WT Arg1-YFP mice i.n. for 3 days. On Day 4, there were higher numbers of Arg1+ ILC2s and macrophages in the lung following IL-33 treatment (Fig. 4D). As IL-33 can induce the production of type 2 cytokines, we investigated whether the increase in the numbers of these two Arg1+ cell types was a result of IL-4/IL-13 signaling. In STAT6-deficient mice treated with rIL-33, Arg1 expression by macrophages was abrogated significantly (Fig. 4D). In contrast, Arg1+ ILC2 numbers remained elevated in the absence of STAT6 signaling. These data demonstrate that IL-33 can increase lung Arg1 in two ways: by STAT6-independent expansion of the pool of constitutively Arg1+ ILC2s and by induction of IL-4/IL-13 leading to STAT6-dependent alternative macrophage activation.

DISCUSSION

Elevated Arg1 expression has been observed in the lung during type 2 inflammation, but a thorough survey of the cells responsible for producing this enzyme has not been performed. In this study, we used an Arg1 reporter mouse to identify cells that express this enzyme in vivo and determined that macrophages and ILC2s express Arg1 in the lung during helminth infection. Although our data confirm prior findings that AAMs are the predominant source of Arg1 in the N. brasiliensis-infected lung based on abundance and enzyme activity/cell [3], we identify ILC2s as the primary hematopoietic source of Arg1 under resting conditions.

Our identification of ILC2s was based on cell surface markers (IL-7Rα, T1/ST2, ICOS, and CD25) and FSC/SSC characteristics widely used to describe IL-5- or IL-13-producing, Lin− cells. Based on these markers, >90% of ILC2s express Arg1 in the resting and infected lung, making this enzyme a consistent marker for lung ILC2s. Thus, the Arg1-YFP reporter mouse may be a useful tool for identifying lung ILC2s in future studies. Although we demonstrated that ILC2s expressed Arg1 in other organs, including the mesenteric LN, spleen, and small intestine, the full characterization of cell populations that express Arg1 in these tissues remains to be determined. Still, Arg1, in combination with other ILC2 genes, may be useful to target these cells genetically without relying on cytokine production for identification. The discovery of new markers for ILC2s remains important, as there are few known ILC2 genes that are distinct from those expressed by T cell subsets.

In this study, we used STAT6-deficient mice to establish that the IL-4/IL-13/STAT6 signaling pathway is not required for Arg1 expression in ILC2s. It remains to be determined how Arg1 transcription is regulated in ILC2s. STAT6-independent mechanisms that induce Arg1 exist in macrophages, although they have not been described during type 2 inflammatory responses. During Mycobacterium bovis infection, Arg1 is regulated by MyD88 and the transcription factor C/EBPβ, which binds to an enhancer upstream of Arg1 and can regulate gene expression in the absence of STAT6 [22]. Although it is unlikely that MyD88 signaling activates Arg1 expression in ILC2s due to the constitutive expression of this enzyme in naive and T1/ST2 knockout mice, involvement of C/EBPβ in ILC2 Arg1 expression will require further investigation. Future studies determining whether the constitutive expression of Arg1 is established during ILC2 development may lead to insights as to how expression of Arg1 is controlled.

IL-33 has been shown to be an important factor in the activation and expansion of ILC2s. Here, we demonstrate that IL-33 can enhance the expression of Arg1 in the lung by regulating the size of the ILC2 compartment but not the level of Arg1 expression/cell. We anticipate that other cytokines that expand ILC2 numbers, such as TSLP and IL-25, will also increase Arg1 expression in the lung by this mechanism. As IL-33, TSLP, and IL-25 are implicated in the initiation of type 2 responses, we speculate that ILC2 recruitment and expansion may represent a rapid mechanism for increasing arginase activity in tissue. Experiments examining the kinetics of ILC2 numbers and macrophage activation after different types of stimuli and in additional tissues will elucidate this further.

The two pathways that serve to enhance Arg1 expression in the lung during type 2 inflammation suggest that this enzyme has important roles in this tissue. Despite this, the function of Arg1 in the lung has been elusive. Our data using mice deficient in Arg1 specifically in ILC2s indicate that Arg1 expression does not affect ILC2 numbers or cytokine production in the lung after worm infection. However, Arg1 was deleted in cells that produce IL-5, and therefore, we cannot exclude a role for the enzyme early in ILC2 development or differentiation. Future studies using alternative strategies to target Arg1 expression in ILCs may shed light on additional functions of these cells and their enzymatic activities.

We speculate that the effects of Arg1 expression by ILC2s will be seen more prominently in environments where AAMs are absent. ILC2s are present in naive mice, and thus, it will be of interest to study whether enzyme production by this cell type is important for maintenance of tissue homeostasis. The immune and metabolic functions of Arg1 expression by ILC2s in various tissues in naive and infected mice remain intriguing areas for investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R37 AI26918, R01 AI30663, PPG HL107202), and the UCSF Sandler Asthma Basic Research Center.

The authors thank Z. Wang for expertise in cell sorting.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 862

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

- AAM

- alternatively activated macrophage

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- Arg1

- arginase-I

- Arg1-flox

- arginase-I-floxed

- Chi3l3

- chitinase 3-like 3

- dpi

- days postinfection

- FSC

- forward-scatter

- ILC2

- type 2 innate lymphoid cell

- i.n.

- intranasally

- KLRG1

- killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G member 1

- Lin

- lineage

- MMR

- macrophage mannose receptor

- Retnla

- resistin-like α

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- SSC

- side-scatter

- TSLP

- thymic stromal lymphopoietin

AUTHORSHIP

J.K.B. and R.M.L. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. J.K.B. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. J.C.N. and H-E.L. generated the Red5 mouse, and H-E.L. generated the Arg1-YFP mouse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Morris S. M., Jr., (2002) Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 22, 87–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sandler N. G., Mentink-Kane M. M., Cheever A. W., Wynn T. A. (2003) Global gene expression profiles during acute pathogen-induced pulmonary inflammation reveal divergent roles for Th1 and Th2 responses in tissue repair. J. Immunol. 171, 3655–3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reece J. J., Siracusa M. C., Scott A. L. (2006) Innate immune responses to lung-stage helminth infection induce alternatively activated alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 74, 4970–4981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zimmermann N., King N. E., Laporte J., Yang M., Mishra A., Pope S. M., Muntel E. E., Witte D. P., Pegg A. A., Foster P. S., Hamid Q., Rothenberg M. E. (2003) Dissection of experimental asthma with DNA microarray analysis identifies arginase in asthma pathogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1863–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pesce J. T., Ramalingam T. R., Mentink-Kane M. M., Wilson M. S., El Kasmi K. C., Smith A. M., Thompson R. W., Cheever A. W., Murray P. J., Wynn T. A. (2009) Arginase-1-expressing macrophages suppress Th2 cytokine-driven inflammation and fibrosis. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barron L., Smith A. M., El Kasmi K. C., Qualls J. E., Huang X., Cheever A., Borthwick L. A., Wilson M. S., Murray P. J., Wynn T. A. (2013) Role of arginase 1 from myeloid cells in Th2-dominated lung inflammation. PLoS One 8, e61961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munder M., Eichmann K., Modolell M. (1998) Alternative metabolic states in murine macrophages reflected by the nitric oxide synthase/arginase balance: competitive regulation by CD4+ T cells correlates with Th1/Th2 phenotype. J. Immunol. 160, 5347–5354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hesse M., Modolell M., La Flamme A. C., Schito M., Fuentes J. M., Cheever A. W., Pearce E. J., Wynn T. A. (2001) Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J. Immunol. 167, 6533–6544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Herbert D. R., Holscher C., Mohrs M., Arendse B., Schwegmann A., Radwanska M., Leeto M., Kirsch R., Hall P., Mossmann H., Claussen B., Forster I., Brombacher F. (2004) Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 20, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nair M. G., Cochrane D. W., Allen J. E. (2003) Macrophages in chronic type 2 inflammation have a novel phenotype characterized by the abundant expression of Ym1 and Fizz1 that can be partly replicated in vitro. Immunol. Lett. 85, 173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stein M., Keshav S., Harris N., Gordon S. (1992) Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J. Exp. Med. 176, 287–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Welch J. S., Escoubet-Lozach L., Sykes D. B., Liddiard K., Greaves D. R., Glass C. K. (2002) TH2 cytokines and allergic challenge induce Ym1 expression in macrophages by a STAT6-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42821–42829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rutschman R., Lang R., Hesse M., Ihle J. N., Wynn T. A., Murray P. J. (2001) Cutting edge: Stat6-dependent substrate depletion regulates nitric oxide production. J. Immunol. 166, 2173–2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pauleau A. L., Rutschman R., Lang R., Pernis A., Watowich S. S., Murray P. J. (2004) Enhancer-mediated control of macrophage-specific arginase I expression. J. Immunol. 172, 7565–7573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moro K., Yamada T., Tanabe M., Takeuchi T., Ikawa T., Kawamoto H., Furusawa J., Ohtani M., Fujii H., Koyasu S. (2010) Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature 463, 540–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Price A. E., Liang H. E., Sullivan B. M., Reinhardt R. L., Eisley C. J., Erle D. J., Locksley R. M. (2010) Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11489–11494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neill D. R., Wong S. H., Bellosi A., Flynn R. J., Daly M., Langford T. K., Bucks C., Kane C. M., Fallon P. G., Pannell R., Jolin H. E., McKenzie A. N. (2010) Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature 464, 1367–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halim T. Y., Krauss R. H., Sun A. C., Takei F. (2012) Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity 36, 451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reese T. A., Liang H. E., Tager A. M., Luster A. D., Van Rooijen N., Voehringer D., Locksley R. M. (2007) Chitin induces accumulation in tissue of innate immune cells associated with allergy. Nature 447, 92–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molofsky A. B., Nussbaum J. C., Liang H-E., Van Dyken S. J., Cheng L. E., Mohapatra A., Chawla A., Locksley R. M. (2013) Innate lymphoid type cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 210, 535–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaplan M. H., Schindler U., Smiley S. T., Grusby M. J. (1996) Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity 4, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. El Kasmi K. C., Qualls J. E., Pesce J. T., Smith A. M., Thompson R. W., Henao-Tamayo M., Basaraba R. J., Konig T., Schleicher U., Koo M. S., Kaplan G., Fitzgerald K. A., Tuomanen E. I., Orme I. M., Kanneganti T. D., Bogdan C., Wynn T. A., Murray P. J. (2008) Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1399–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoshino K., Kashiwamura S., Kuribayashi K., Kodama T., Tsujimura T., Nakanishi K., Matsuyama T., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) The absence of interleukin 1 receptor-related T1/ST2 does not affect T helper cell type 2 development and its effector function. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1541–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Voehringer D., Shinkai K., Locksley R. M. (2004) Type 2 immunity reflects orchestrated recruitment of cells committed to IL-4 production. Immunity 20, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corraliza I. M., Campo M. L., Soler G., Modolell M. (1994) Determination of arginase activity in macrophages: a micromethod. J. Immunol. Methods 174, 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Camberis M., Le Gros G., Urban J., Jr. (2003) Animal model of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 19, Unit 19.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iyer R. K., Yoo P. K., Kern R. M., Rozengurt N., Tsoa R., O'Brien W. E., Yu H., Grody W. W., Cederbaum S. D. (2002) Mouse model for human arginase deficiency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4491–4498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.