Programmed cell death ligand-1 gene deficiency attenuates liver sinusoidal endothelial cell injury in sepsis, resulting from interactions with programmed cell death receptor-1 expressing Kupffer cells.

Keywords: hepatic endothelium, septic inflammation, liver immune tolerance, acute liver failure, coinhibitory molecules

Abstract

PD-1 and PD-L1 have been reported to provide peripheral tolerance by inhibiting TCR-mediated activation. We have reported that PD-L1−/− animals are protected from sepsis-induced mortality and immune suppression. Whereas studies indicate that LSECs normally express PD-L1, which is also thought to maintain local immune liver tolerance by ligating the receptor PD-1 on T lymphocytes, the role of PD-L1 in the septic liver remains unknown. Thus, we hypothesized initially that PD-L1 expression on LSECs protects them from sepsis-induced injury. We noted that the increased vascular permeability and pSTAT3 protein expression in whole liver from septic animals were attenuated in the absence of PD-L1. Isolated LSECs taken from septic animals, which exhibited increased cell death, declining cell numbers, reduced cellular proliferation, and VEGFR2 expression (an angiogenesis marker), also showed improved cell numbers, proliferation, and percent VEGFR2+ levels in the absence of PD-L1. We also observed that sepsis induced an increase of liver F4/80+PD-1+-expressing KCs and increased PD-L1 expression on LSECs. Interestingly, PD-L1 expression levels on LSECs decreased when PD-1+-expressing KCs were depleted with clodronate liposomes. Contrary to our original hypothesis, we document here that increased interactions between PD-1+ KCs and PD-L1+ LSECs appear to lead to the decline of normal endothelial function—essential to sustain vascular integrity and prevent ALF. Importantly, we uncover an underappreciated pathological aspect of PD-1:PD-L1 ligation during inflammation that is independent of its normal, immune-suppressive activity.

Introduction

Sepsis is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States and the leading cause of death in critically ill patients [1]. Sepsis often progresses to MODS, which is characterized the by the physiological breakdown of two or more organs. Whereas liver dysfunction is not the most common form of organ injury encountered in the septic patient, when it culminates into ALF, this becomes a grave complication [2]. Therefore, it is important to understand the pathophysiological changes that contribute to liver dysfunction associated with the development of MODS, which has been defined as the combination of cellular injury in addition to heightened inflammation.

ECs contribute to the complex pathology associated with MODS [3]. EC activation and dysfunction play major roles in MODS. We have shown recently that LSECs undergo Fas-mediated apoptosis and are susceptible to injury during sepsis [4]. We have also shown that KCs protect LSECs from further sepsis-induced injury [4]. LSECs, along with KCs, remain as the predominant NPC types of the hepatic sinusoid [5]. In addition to LSECs and KCs, the hepatic sinusoid contains an array of other immunologically active cells, including DCs. All (LSECs, DCs, and KCs) have been shown to recognize endotoxin, express TLR4, and play a role in liver immune tolerance [5].

Under normal conditions, the liver does not respond to food and microbial antigens that come from the intestine; all of the blood that passes through the intestine and spleen is eventually delivered to the liver. Instead, the liver's metabolic functioning allows it to produce neoantigens and maintain a liver-tolerance effect [6]. This “liver tolerance effect”, classified in 1969, is known as the liver's ability to induce an antigen-specific immune tolerance [7]. Contrary to vascular ECs, LSECs have the capacity to function as APCs and through their presentation of “neoantigens”, are considered to be major contributors of the liver immune-tolerance state [8].

It has been proposed that LSECs also contribute to the state of immune homeostasis through their expression of PD-L1 [9]. ECs, along with epithelial cells and a variety of APCs, have been reported to express PD-L1, which is the ligand for the coinhibitory receptor PD-1, which is expressed on B and T cells, as well as myeloid cells. The engagement of PD-1 to PD-L1 leads to the inhibition of TCR-mediated activation, proliferation, and cytokine secretion [10]. Whereas the role of PD-1: PD-L1 signaling has been addressed extensively in cancer and viral-infection models, its role in sepsis has only been recently studied [11, 12]. We have shown that PD-1−/− mice are protected from sepsis-induced lethality. Other groups [13–15] that have administered anti-PD-1- and/or anti-PD-L1-blocking antibodies to septic animals have confirmed this finding with similar results. More recently, LSECs have been shown to present soluble antigens to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. PD-L1 expression on LSECs has been shown to bind and ligate PD-1 on naïve CD8+ T cells in vitro—classified as a tolerogenic phenotype: CD127+, CD122+, and Bcl-2+ [9]. It has also been proposed that PD-L1 expression on vascular ECs may serve to modulate local angiogenesis [16]. Yet, the role of PD-L1 in the septic liver remains unknown.

As the liver has adapted specialized mechanisms to maintain immune tolerance, we believe that by better understanding how the tolerogenic capacities of LSECs are affected and possibly involved during septic inflammation, we would grasp a clearer perspective into the pathological processes underpinning the development of ALF. In this study, we wanted to determine how the expression of PD-L1 on LSECs affects their function during sepsis. Here, we report that in the absence of PD-L1, LSECs are less prone to injury and more likely to express proangiogenic and/or survival factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and animal use

Experimental protocols performed within this study have been approved by the Animal Care Usage Committee at Rhode Island Hospital (Providence, RI, USA) and meet the standards set forth by the U.S. National Institutes of Health's Guide for Laboratory Animal Use and Care. PD-L1−/− (or B7-H1−/− on C57BL/6 background) animals were bred in-house; the breeders were provided originally as a generous gift from Dr. Lieping Chen (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA). Age-matched C57BL/6 male mice (7–9 weeks of age) were ordered from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).

CLP animal surgery

Male mice were anesthetized by isoflurane, and a midline incision was made below the diaphragm. The cecum was exposed, ligated with a sterile silk thread, and then punctured twice with a 22-gauge needle. One puncture occurred closest to the site of ligation, whereas the other was distal to the site of ligation. Fecal material was allowed to exude from the punctured cecum, and then it was put back into the abdominal cavity. The visceral and skin layers were sewn back into place with a 6.0-nylon suture, and the site of incision was numbed with lidocaine. Animals were resuscitated with 1.0 mL lactate Ringer's solution. Sham control surgery was performed, but the cecum was neither ligated nor punctured [17].

Western blotting—protein expression of total STAT3 and pSTAT3

Twenty-four hours post-Sham and/or CLP surgery, animals were killed by CO2 overdose. Liver tissues from each animal were then harvested and placed into lysis buffer (containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaFl, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 10 mM PMSF, in addition to a protease inhibitor cocktail). Samples were homogenized, left on ice for 30 min, and spun at 9300 g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell lysates (45 μg protein, as determined by a Bradford protein assay) were loaded equally onto 10% polyacrylamide gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Life Technologies). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 10% nonfat dry milk in PBST and then probed with anti-mouse pSTAT3 (Ty705) and total STAT3 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C in 5% BSA + PBST. After primary antibody incubation, membranes were washed three times in PBST, and rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was added at a concentration of 1:2000 in 3% BSA + PBST. Membranes were developed by chemiluminescence using an Amersham prime ECL Plus detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). GAPDH was used as a loading control, and densitometric analyses were performed as reported previously by our laboratory [18].

Vascular leakage assay

Twenty-four hours post-Sham and/or CLP surgery, animals were i.v.-injected with 200 μl 0.5% (w/v) EBD (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); we performed this liver vascular leakage procedure according to the methods of Zellweger et al. [19]. The dye was allowed to percolate to the subendothelial spaces for 15 min, and then, the mice were killed by CO2 overdose. Whole livers were perfused with 1× PBS, weighed, and then dissociated with formamide (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h at 37°C. After 2 days, supernatants were spun down and read on a spectrophometer at 610 nm. The amount of vascular leakage or EBD extracted from each liver sample was calculated by the OD value, and concentration (mg/mL) was normalized to the amount of EBD (mg/mL) collected in the serum.

NPC isolation and LSEC (CD146+) magnetic bead enrichment

Animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation, 24 h post-CLP and/or -Sham surgery. We have reported the NPC isolation protocol previously [4], modified from Katz et al. [20]. In brief, liver tissue was perfused with collagenase buffer, extracted, and digested for 30–35 min at 37°C. Single-cell suspension samples were then collected in 40-μm strainers, and hepatocyte pellets were removed by slow centrifugation at 30 g for 10 min at 4°C. Cells in supernatant were enriched by 30% histodenz (Sigma-Aldrich) and spun down at 1650 g for 30 min at 4°C. NPCs, at the interface layer, were collected, washed, counted, and set aside for magnetic bead enrichment—CD146+ cells were separated and purified from NPCs by positive-selection CD146+ beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). Phenotype and purity were confirmed by flow cytometry on a BD FACSArray—50,000 events.

Flow cytometry

NPCs and/or CD146+-enriched LSECs were blocked with Fc Receptor block antibody (CD16/CD32; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. For PD-L1 staining, NPCs were stained for extracellular markers, anti-mouse CD45-PECy7 (eBioscience), and anti-mouse CD146-PE (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), in combination with anti-mouse PD-L1-allophycocyanin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 45 min at 4°C. For KC, PD-L1, and PD-1 staining, NPCs were stained with extracellular markers, anti-mouse F4/80-allophycocyanin (eBioscience), PD-L1-PE (eBioscience), and/or PD-1-PE (eBioscience) for 45 min at 4°C. For Annexin V staining, enriched LSECs were stained initially for extracellular markers, anti-mouse CD45-PECy7, and anti-mouse CD146-PE for 30 min at room temperature. Next, cells were spun down, resuspended in 1× binding buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and stained with Annexin V (BD Biosciences) for 15 min at room temperature. For Fas staining, enriched LSECs were stained for anti-mouse CD146-PE, CD45-PECy7, and Fas biotin (eBioscience) for 30 min at room temperature. Next, streptavidin-allophycocyanin was added for 15 min at room temperature. For VEGFR2 staining, enriched LSECs were stained with anti-mouse CD146-PE, CD45-PECy7, and VEGFR2-allophycocyanin (CD309; eBioscience) for 45 min at 4°C. For Ki67 staining, enriched LSECs were stained initially for extracellular markers, anti-mouse CD146-PE, and CD45-PECy7 for 30 min at room temperature. After extracellular staining, cells were then fixed and permeabilized in 1× eBioscience fixation/permeabilization solution for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed twice in 1× permeabilization buffer and stained for anti-mouse Ki67-allophycocyanin, an intracellular marker (eBioscience). Isotype controls for each staining condition were also stained at the same time as indicated by each manufacturer. After each staining condition, cells were washed 2× and then read on a BD FACSArray—50,000 events. Flow cytometry data were analyzed by FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

KC depletion

Clodronate and PBS control liposomes (provided by Dr. Nico van Roojen, Amsterdam, Netherlands) were mixed, diluted 1:5 in 1× PBS, and then i.v.-injected (total volume of 200 μl) into C57BL/6 animals [21]. Two days later, Sham and/or CLP surgery were performed on these mice.

Statistical analyses

All data collected in this study were analyzed and graphed by Prism v5 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Graphs are displayed as the mean ± sem. Significant differences were confirmed between groups when P < 0.05. P values were determined by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test for two groups and a nonparametric one-way ANOVA test for more than two groups.

Online Supplemental material

Typical gating strategies (representative flow cytometry dot-plots and histogram overlays) for enriched LSECs (gated on the CD146+CD45− population), stained for Ki67, are displayed in Supplemental Fig. 1, along with a detailed legend description.

RESULTS

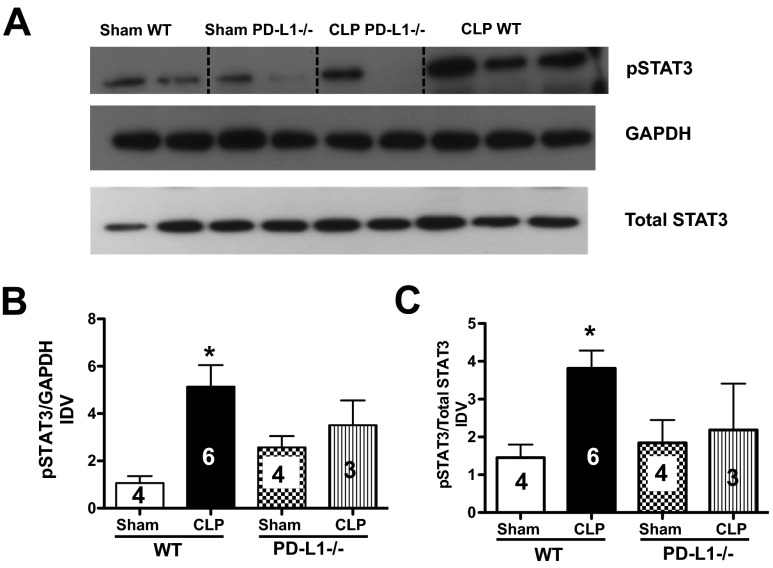

PD-L1 modulates pSTAT3 expression in the liver

Interestingly, it has been proposed that STAT3 regulates PD-L1 expression of tolerogenic APCs (primarily DCs) by binding to the PD-L1 promoter [22]. STAT3 has also been shown to protect the whole liver from Fas-induced injury [23]. As we have shown that sepsis-induced injury leads to an up-regulation of Fas and FasL in the liver [24], we decided to determine how STAT3 activation (increased pSTAT3) was affected in the presence or absence of PD-L1 in the livers, taken from septic animals. Here, we found that pSTAT3 increased in WT (C57BL/6) CLP mouse liver tissues when compared with Sham controls. However, whereas no change was observed between Sham and CLP PD-L1−/− mice, there was a trend toward a decrease in CLP PD-L1−/− compared with CLP WT mouse livers (Fig. 1A–C). This data suggest that the whole liver might be protected partially from sepsis-induced injury in the absence of PD-L1. As we looked at the levels of pSTAT3 in whole liver tissue homogenates, which include hepatocytes, we decided to determine whether PD-L1 directly affects the sinusoidal endothelium in our next set of experiments.

Figure 1. PD-L1 modulates pSTAT3 expression in whole liver tissue in response to CLP.

(A) Representative Western blot, depicting cell lysates probed for pSTAT3, total STAT3, and GAPDH from Sham and CLP WT and PD-L1−/− animals. Dashed, black line identifies the sample. Bands were detected at 79, 86, and 37 kDa, respectively. (B and C) Densitometric analyses were performed on pooled Sham and CLP protein samples from WT and PD-L1−/− animals. Graphs indicate the densitometry quantification expressed as image density value (IDV) over total STAT3 and/or GAPDH. There is an increase of pSTAT3 expression (compared with GAPDH and total STAT3) in CLP WT livers versus Sham, n = 3–6, *P < 0.05. There is a declining trend of pSTAT3 expression in CLP PD-L1−/− livers: P > 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus CLP WT; P > 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus Sham PD-L1−/−. P values determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean ± sem. The numbers on the bars within this panel reflect the animals in each experimental group.

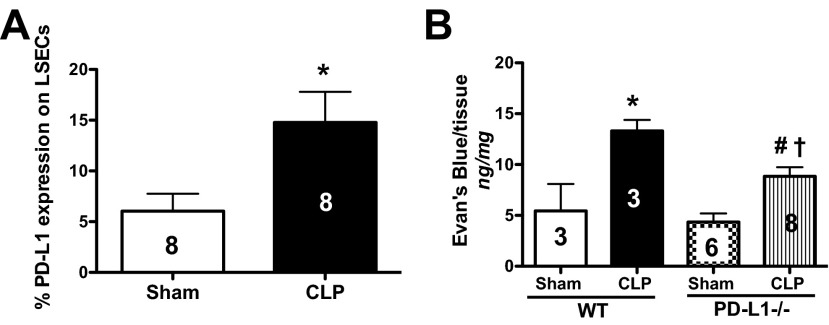

CLP-induced PD-L1 expression on LSECs affects liver tissue vascular permeability

LSECs have been reported to constitutively express PD-L1 [25]. To assess if sepsis affects PD-L1 expression on LSECs, we isolated NPCs and phenotyped the expression of PD-L1 on LSECs by flow cytometry (defined as CD146+CD45−PD-L1+-expressing cells). Initially, we found that LSECs up-regulated PD-L1, 24 h after CLP in WT mice (Fig. 2A). We then determined how liver tissue permeability was affected in the presence and/or absence of PD-L1. With the use of a vascular leakage assay, we found that there was more EBD extravasation into the tissues of CLP WT mouse livers compared with Sham WT controls, and this decreased in CLP PD-L1−/− animals (Fig. 2B). We also noted that sepsis induced an overall increase in liver tissue vascular permeability, as CLP PD-L1−/− animals also exhibited an increase of EBD leakage compared with their respective Sham controls (Fig. 2B). Collectively, these results suggest that not only is PD-L1 expression on LSECs increased in response to septic insult, but also, the expression of this gene directly contributes to elevated vascular permeability and localized tissue edema in sepsis. These processes are thought to play a significant role in organ dysfunction.

Figure 2. Increased PD-L1 expression on LSECs in response to CLP impacts liver tissue vascular permeability.

(A) LSECs up-regulate PD-L1 expression, 24 h post-CLP in WT animals, n = 8/group; *P < 0.05, CLP versus Sham WT, determined by a Mann-Whitney t-test. The numbers on the bar reflect the animals in each group. (B) There is more albumin protein leakage, as assessed by EBD, in liver tissue taken from CLP versus Sham WT animals, n = 3–8 group; *P < 0.05, CLP WT versus Sham WT. The increased EBD extravasation decreases in CLP PD-L1−/− animals, n = 3–8/group; #P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus CLP WT; †P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus Sham PD-L1−/−. P values were determined by a one-way ANOVA nonparametric test. All data in this panel are expressed as mean ± sem. The numbers on the bars within this panel reflect the animals in each experimental group.

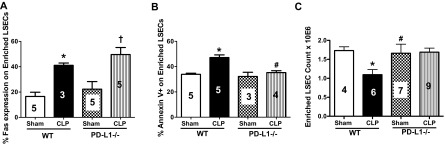

PD-L1−/− attenuates CLP-induced LSEC apoptosis and cell loss, independent of Fas expression

PD-1 was isolated originally from a T cell hybridoma that was undergoing programmed cell death [26]. Although it was isolated in the context of hunting for genes that regulate apoptosis, it was subsequently revealed that the function of PD-1 is not directly related to immune cell apoptosis but instead, promotes T cell anergy [27]. We have reported previously that LSECs undergo Fas-mediated apoptosis in sepsis [4]. We have also shown that LSECs have increased Fas expression after CLP in WT mice [4]. To confirm further that PD-1:PD-L1 signaling and Fas:FasL signaling are independent events, we chose to determine Fas expression on LSECs from WT and PD-L1−/− mice. Isolated LSECs ex vivo from CLP WT and CLP PD-L1−/− animals had an up-regulation of the Fas death receptor compared with their corresponding Sham controls (Fig. 3A). Whereas Fas:FasL and PD-1:PD-L1 may remain as independent signaling events, whole liver tissue permeability was still affected. Therefore, we decided to stain isolated LSECs ex vivo for an apoptosis marker, Annexin V, in WT and PD-L1−/− mice. Here, we found that LSECs from septic WT animals had an increase of Annexin V staining, and this was mitigated in LSECs from CLP PD-L1−/− animals (Fig. 3B). When we looked at total cell numbers, we also found that there was a twofold decrease in LSEC numbers from CLP WT animals, and these numbers were restored in CLP PD-L1−/− animals (Fig. 3C). These data collectively indicate that whereas Fas-mediated apoptosis of LSECs is independent of PD-L1 in sepsis, PD-L1 expression on LSECs still does impact sepsis-induced endothelium injury and cell loss.

Figure 3. Independent but synergetic effects of Fas and PD-L1 expression on CLP-induced mouse LSEC loss and apoptosis.

(A) Fas:FasL and PD-1:PD-L1 signaling events are independent of one another during sepsis. There is an increase of Fas expression on isolated LSECs from CLP WT and CLP PD-L1−/− animals versus their respective controls, n = 3–5; *P < 0.05, CLP versus Sham WT; †P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus Sham PD-L1−/−. P values were determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA test. (B) There is an increase of Annexin V staining on isolated LSECs from CLP versus Sham WT animals, and this staining decreases in CLP PD-L1−/− LSECs, n = 3–6/group; *P < 0.05, CLP versus Sham WT; #P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus CLP WT. P values determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA. (C) There is a decrease in LSEC number in CLP versus Sham WT animals, and these LSEC numbers are rescued in CLP PD-L1−/− animals, n = 4–8; *P < 0.05, CLP WT versus Sham WT; #P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus CLP WT. P values determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA. All data in this panel are expressed as mean ± sem. The numbers on the bars within this panel reflect the animals in each experimental group.

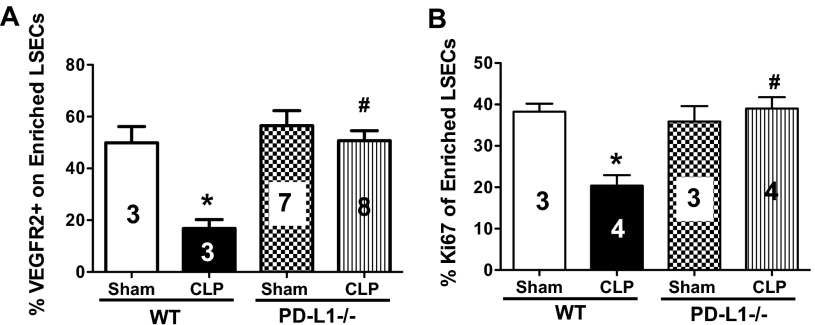

Lack of PD-L1 expression restores LSEC angiogenesis and proliferation

PD-L1 has been shown to regulate EC angiogenesis and proliferation in vitro but not in vivo [16]. Therefore, we decided for the next set of experiments to determine if PD-L1 expression on LSECs would directly affect their ability to undergo angiogenesis and cellular proliferation—important EC functions in maintaining vascular integrity. We noted initially that isolated LSECs from CLP WT had a significant decrease in VEGFR2, classified as CD146+CD45−VEGFR2+-expressing cells, as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A). Yet, the percentage of VEGFR2 expression on LSECs was restored in the CLP PD-L1−/− animals (Fig. 4A). VEGFR2 is not only a marker of angiogenesis, but also, it can be a good indicator of EC permeability, barrier function, and vitality. VEGFR2 is the receptor to the growth factor VEGF, which has been shown to be a crucial regulator of vascular development during embryogenesis, and new blood vessel formation in adults [28]. The down-regulation of VEGFR2 on LSECs in sepsis suggests that these cells are less viable.

Figure 4. PD-L1 expression on mouse LSECs modulates angiogenesis and cellular proliferation in response to CLP.

(A) There is a decrease of VEGFR2 expression on LSECs from CLP versus Sham WT animals, and this returns to Sham WT levels in LSECs from CLP PD-L1−/− animals, n = 3–8; *P < 0.05, CLP WT versus Sham WT; #P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus CLP WT. P values were determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA test. (B) LSECs from CLP versus Sham WT animals proliferate less, n = 3–4; *P < 0.05, CLP WT versus Sham WT; there is greater proliferation in LSECs from CLP PD-L1−/− animals; #P < 0.05, CLP PD-L1−/− versus CLP WT (see Supplemental Fig. 1 for Ki67+ gating strategy). P values determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA. All data in this panel are expressed as mean ± sem. The numbers on the bars within this panel reflect the animals in each experimental group.

We decided further to confirm our earlier observations that LSECs from CLP PD-L1−/− animals are protected from sepsis-induced injury and cell loss by looking at cell proliferation, as predicted by the change in intracellular Ki67 expression [29]. The Ki67 protein is actively expressed during all phases of the cell cycle, except when the cells are at a resting stage (G1/G0). Reports with flow cytometry experiments have shown that there are low percentages of Ki67-positive mature and primary-cultured ECs, whereas embryonic and transformed ECs exhibit higher percentages of Ki67 [30, 31]. We observed that isolated ex vivo LSECs from CLP WT animals had decreased percentage Ki67+ staining compared with their Sham controls, and this was restored in the LSECs from CLP PD-L1−/− animals (see Supplemental Fig. 1 for Ki67+ gating strategy and Fig. 4B for summary data of repeated experiments). Thus, LSECs from septic animals appear to proliferate and undergo cellular divisions at a reduced rate that is necessary to sustain normal homeostatic functions of ECs.

PD-1+-expressing KCs potentiate LSEC injury in sepsis

Our initial hypothesis was that PD-L1 expression on LSECs would protect them from sepsis-induced injury, as this molecule should be involved in driving immune suppression. However, up until this point, our data have suggested the opposite of this hypothesis and that PD-L1 expression on LSECs was actually mediating detrimental affects. Next, we decided to determine if the PD-1+-expressing cell population was potentially responsible for the observed functional changes in LSECs during sepsis, and if so, what were the changes? Initially, we noted an increase in the percent of and F4/80+PD-L1+- and F4/80+PD-1+-expressing cells in the liver, 24 h post-CLP (Fig. 5A and B). These cells are typically classified as KCs [32], and we chose to determine what effect ablating them by clodronate liposomes would have on the expression of PD-L1 on LSECs. We observed that the marked rise in the ex vivo frequency of PD-L1+ expression on LSECs derived from CLP WT animals was attenuated in CLP clodronate-treated (KC-depleted) animals (Fig. 5C). Overall, these data imply that PD-1+ KCs are likely interacting with PD-L1 on LSECs during sepsis, and this ligation alters normal EC functions, culminating in increased vascular permeability and liver injury.

Figure 5. PD-1.

+-expressing KCs ligate PD-L1 on LSECs during CLP. (A) There is an increase of liver F4/80+PD-L1+-expressing KCs following WT CLP at 24 h, CLP WT versus Sham WT, n = 5–8/group; *P < 0.05, determined by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney t-test. (B) There is an increase of liver F4/80+PD-1+-expressing KCs following WT CLP at 24 h versus Sham WT, n = 8/group; *P < 0.05, determined by a nonparametric Mann Whitney t-test. (C) There is an increase of PD-L1 expression on LSECs from CLP PBS control animals, n = 4–5/group; *P < 0.05, CLP PBS versus Sham PBS. PD-L1 expression levels on LSECs in CLP-KC-depleted animals (clodronate-treated) decreases; #P < 0.05, CLP-clodronate versus CLP PBS. P values were determined by a nonparametric one-way ANOVA test. All data in this panel are expressed as mean ± sem. The numbers on the bars within this panel reflect the animals in each experimental group.

DISCUSSION

The PD-1:PD-L1 pathway has not only been shown to promote septic morbidity but also to contribute to sepsis-induced immunosuppression—a key aspect of critical illness found in septic shock patients [21]. We have reported that PD-L1−/− animals are protected from sepsis-induced lethality and have decreased immune suppression [13]. Zhang et al. [15] have reported that when an anti-PD-L1-blocking antibody was administered to septic mice, their overall survival improved. They also found that this correlates with a decrease in T lymphocyte apoptosis and the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10. Yet, in lieu of these findings, the absence of PD-1 and more specifically, PD-L1 has not been linked directly to the pathology of MODS and how its expression on ECs contributes to this process. In this study, we demonstrate that PD-L1−/− also has beneficial effects on EC vitality and survival, which directly impact overall liver tissue permeability. Yet, these results are also potentially contrary to the proposed normal or homeostatic functions that have been attributed to PD-L1 found in the liver.

Under normal or homeostatic conditions, LSECs are considered to be unique APCs that not only cross-present antigen but also through their PD-L1 expression, can interact with PD-1 on naïve CD8+ T cells to promote immune tolerance and dampen local inflammation [33]. For example, PD-L1 on LSECs has also been shown to inhibit cytokine release of TH17 and TH1 cells by ligating its receptor, PD-1 [34]. Outside of the context of the liver, vascular ECs in vitro have been also shown to inactivate CD8+ T cell cytokine secretion through the expression of PD-L1s [35]. Therefore, our original hypothesis was that PD-L1 on LSECs would protect them from sepsis-induced injury and help to attenuate local inflammation. However, we believe, based on data presented here, that the normal functions of LSECs to provide immune-tolerant signals eventually become lost in response to sepsis. As a result of the up-regulated expression of PD-L1 on LSECs, increased interactions with PD-1+-expressing leukocytes, such as KCs, eventually lead to their demise.

LSECs have been reported to constitutively express PD-L1 [25]. We have noted that LSECs up-regulate PD-L1 expression during the response to sepsis (Fig. 2B). These findings correlate with studies in other liver viral infection models, which have suggested that PD-L1 may be a marker of chronic inflammation, where there are indices of active liver disease [36]. PD-L1 has been shown to be up-regulated on chronically inflamed livers, as evidence by liver biopsies from HBV and HCC human patients [37]. It has also been reported that there are increased PD-L1 expression levels during the active phases of HBV infection, in contrast to decreased expression levels of PD-L1 on LSECs and KCs during inactive/quiescent phases [38]. Up-regulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 also corresponds with viral persistence during active HCV infection [39].

We also found that there is a partial decrease in pSTAT3 protein expression in whole liver tissue homogenates taken from septic PD-L1−/− animals compared with WT septic animals alone (Fig. 1). STAT3 has been shown to not only protect hepatocytes from Fas-induced injury but also to be required for liver regeneration [23]. In the absence of PD-L1, the whole liver tissue trends toward a decrease in pSTAT3 expression compared with septic WT livers but still increased in comparison with its own Sham control (CLP PD-L1−/− vs. Sham PD-L1−/−; Fig. 1B). This might be explained by the marked rise of Fas expression on LSECs in the presence and absence of PD-L1 (Fig. 4A). Although the expression profiles of Fas and PD-L1 are distinct, both molecules are considered to maintain peripheral immune tolerance in select situations. The primary difference, however, resides in how FasL and PD-L1 are proposed to function. Fas:FasL signaling has been shown to cause T cell deletion and work independently of the costimulatory signal CD28, whereas PD-1:PD-L1 signaling requires CD28 [40–42]. In addition, their downstream signaling cascades are unique: Fas:FasL signaling uses the recruitment of death receptor-associated caspases and kinases, whereas PD-L1:PD-1 signaling uses phosphatases [43, 44].

Interestingly, the most relevant topic for EC viability and survival is maintenance of their angiogenic capacity. Angiogenesis is required for liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy [45]. Here, we show that LSECs from WT septic animals have less ex vivo evidence of cellular proliferation compared with Sham controls or CLP PD-L1−/− animals (Fig. 4). In fact, LSEC progenitor cells have been shown to be required for liver regeneration in rats [46], making continual EC proliferation and replenishment of LSECs essential for restoring liver tissue function in cases of injury, such as sepsis. PD-L1 on vascular ECs has been shown to modulate angiogenesis in vitro, but it has not been implicated in a sepsis model or in vivo [16]. Here, we found that VEGFR2 expression decreases dramatically on LSECs during sepsis, and this is restored in CLP PD-L1−/− animals (Fig. 4). We also noted that LSECs from CLP PD-L1−/− mice exhibited decreased cell loss and apoptosis (Fig. 3B and C). These results are consistent that PD-L1 ligation modulates angiogenesis in vascular ECs [16] but also indicate that sepsis causes a loss of LSEC numbers and down-regulation of VEGFR2 and overall, affects the sinusoidal endothelium's ability to respond to VEGF and form new blood vessels. In addition, our findings of decreased VEGFR2 levels on septic LSECs correlate with a study that indicated that there are increased circulating levels of VEGF in blood-serum samples from septic patients and animals [47]. Perhaps there is an increase of VEGF, as the receptor has been down-regulated on ECs, as we have observed. Even though the functional significance of the rise in blood VEGF levels is debated, it appears to be a good indicator of developing septic morbidity and/or organ injury [47].

Although we found that PD-L1−/− promotes LSEC survival and angiogenesis, we also believe that PD-1+-expressing KCs drive the pathological process of LSEC dysfunction. The interaction between PD-L1 on the LSEC and PD-1 on the KC promotes the associated pathology of immune-tolerance breakdown and overall cell injury. Whereas most studies have indicated that LSECs and KCs are the primary cell populations that express PD-L1, we show here that KCs express PD-1 and found that there is an increased frequency of F4/80+PD-1+ cells in the liver during sepsis (Fig. 5B) [48]. There are also supporting data from other studies that have indicated that monocytes and/or KCs up-regulate their PD-L1 expression during septic shock, autoimmune liver disease, and HCC (Fig. 5A) [49–51]. For example, PD-L1 expression on KCs has been shown to interact with PD-1+-expressing CD8+ T cells and down-regulate their autoreactivity in autoimmune liver disease [50]. PD-L1 expression on KCs has also been proposed to suppress T lymphocyte effector functions during heightened inflammation, such as HCC. When a PD-L1-blocking antibody was incubated with CD8+ T cells from HCC patients ex vivo, T cells exhibited better effector functions, such as cytokine secretion and proliferative ability. Perhaps in these forms of liver injury, PD-L1 on KCs does serve to balance local inflammation by signaling to PD-1+-expressing CD8+ T cells [51]. We have shown that CD8+ T cells are not involved directly in LSEC injury [4]. This could also explain why we see that sepsis results in an increased percentage of F4/80+PD-L1+ cells in the liver, but these cells are not responsible for the observed effects on hepatic endothelial function, as they are signaling to CD8+ T lymphocytes [52].

Yet, it has also not been shown that KCs express PD-1, making our results novel. We have reported, however, that peritoneal macrophages express PD-1, and this cell population is essential for the protection from septic-induced mortality seen in PD-L1−/− animals [13]. We further add to the story, however, by also confirming that PD-1+-expressing KCs (F4/80+PD-1+) do contribute to EC dysfunction by ligating PD-L1 on LSECs. In the absence of KCs, there is an attenuation of PD-L1 expression on isolated LSECs from septic animals, which under septic conditions, becomes up-regulated (Figs. 2B and 5C).

In summary, we show here the first evidence that PD-L1 on LSECs potentially impacts and contributes to the pathology of ALF that occurs during septic shock. We believe this process to be dependent on the interactions between PD-1+-expressing KCs and PD-L1 on the sinusoidal endothelium. Most studies have suggested that targeting and/or blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway would be a good strategy to combat immune suppression seen in critically ill patients [53], but we now also think that this stands true for the protection of EC function, hepatic microcirculation, and indirectly, the suppression of MODS that develops during septic challenge. Whereas LSECs are prone to Fas-mediated apoptosis during septic inflammation, this may not be the sole mechanism of injury. We propose that the increased expression of Fas and PD-L1 on the endothelium may synergize to elicit marked increased interactions with FasL+ and PD-1+ leukocytes. The Fas:FasL and PD-1:PD-L1 signaling pathways are discreet from one another, but their combined effects could exacerbate local LSEC injury and/or cell death.

The potential clinical implications of this work not only confirm that PD-L1 is a marker of liver inflammation, as proposed previously [36] but also may predict disease outcome based on the expression levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 on liver macrophage populations. KCs may have differential effects on the liver during inflammation, and inflammation, in general, reorganizes the expression levels of PD-L1, shifting the liver from away from its normal immune-quiescent state. Inflammatory monocytes have been reported to express high levels of PD-L1, whereas resident macrophages, such as KCs, express low levels [54]. Yet, perhaps during inflammation or situations similar to sepsis, infiltrating monocytes can modulate the expression levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 on resident macrophage populations. This may be why we see two distinct F4/80+ populations (Fig. 5A and B). In fact, it has been proposed in other liver-infection models, such as an experimental animal model of fibrosis, that distinct subpopulations of macrophages play both roles in fibrosis progression and regression [55, 56]. One population acts in an anti-inflammatory fashion, and the other secretes proinflammatory cytokines to activate other liver cell populations. Thus, it would be worthwhile in future studies to investigate how modulating PD-L1-expression levels in the liver impacts KCs and ultimately, disease progression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the following grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health: F31-DK083873 and T32-GM065085 (to N.A.H.) as well as R01-GM053209 and R01-GM046354 (to A.A.).

The authors thank Professor Nico van Roojen (Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Vrije University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, Netherlands) for providing the clodronate and PBS control liposomes that were used to deplete KCs in this study. They thank Dr. Lieping Chen (Department of Cancer Immunology, Yale University School of Medicine) for providing the breeders for the PD-L1−/− mice that were used in this study.

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

- −/−

- deficient

- ALF

- acute liver failure

- CLP

- cecal ligation and puncture

- EBD

- Evan's blue dye

- EC

- endothelial cell

- FasL

- Fas ligand

- HBV/HCV

- hepatitis B/C virus

- HCC

- hepatic cell carcinoma

- KC

- Kupffer cell

- LSEC

- liver sinusoidal endothelial cell

- MODS

- multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- NPC

- nonparenchymal cell

- PBST

- PBS-Tween-20

- PD-1

- programmed death receptor-1

- PD-L1

- programmed death ligand-1

- pSTAT3

- phosphorylated STAT3

AUTHORSHIP

N.A.H. designed and executed all experiments presented herein, as well as conducted statistical data analyses, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript. C-S.C. assisted with experiments and edited the written manuscript. F.W. performed flow cytometry experiments to determine the percentage of PD-1+ on F4/80+ NPCs (Fig. 5B). Y.W. performed flow cytomery experiments to determine the percentage of PD-L1 on F4/80+ NPCs (Fig. 5A). A.A. oversaw the study, as well as reviewed and edited the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Angus D. C., Linde-Zwirble W. T., Lidicker J., Clermont G., Carcillo J., Pinsky M. R. (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 29, 1303–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canabal J. M., Kramer D. J. (2008) Management of sepsis in patients with liver failure. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 14, 189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aird W. C. (2003) The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 101, 3765–3777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hutchins N. A., Chung C. S., Borgerding J. N., Ayala C. A., Ayala A. (2013) Kupffer cells protect liver sinusoidal endothelial cells from Fas-dependent apoptosis in sepsis by down-regulating gp130. Am. J. Pathol. 182, 742–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crispe I. N. (2009) The liver as a lymphoid organ. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 147–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tiegs G., Lohse A. W. (2010) Immune tolerance: what is unique about the liver. J. Autoimmun. 34, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calne R. Y., Sells R. A., Pena J. R., Davis D. R., Millard P. R., Herbertson B. M., Binns R. M., Davies D. A. (1969) Induction of immunological tolerance by porcine liver allografts. Nature 223, 472–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Limmer A., Ohl J., Kurts C., Ljunggren H. G., Reiss Y., Groettrup M., Momburg F., Arnold B., Knolle P. A. (2000) Efficient presentation of exogenous antigen by liver endothelial cells to CD8+ T cells results in antigen-specific T-cell tolerance. Nat. Med. 6, 1348–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diehl L., Schurich A., Grochtmann R., Hegenbarth S., Chen L., Knolle P. A. (2008) Tolerogenic maturation of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells promotes B7-homolog 1-dependent CD8+ T cell tolerance. Hepatology 47, 296–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freeman G. J., Long A. J., Iwai Y., Bourque K., Chernova T., Nishimura H., Fitz L. J., Malenkovich N., Okazaki T., Byrne M. C., Horton H. F., Fouser L., Carter L., Ling V., Bowman M. R., Carreno B. M., Collins M., Wood C. R., Honjo T. (2000) Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1027–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Day C. L., Kaufmann D. E., Kiepiela P., Brown J. A., Moodley E. S., Reddy S., Mackey E. W., Miller J. D., Leslie A. J., DePierres C., Mncube Z., Duraiswamy J., Zhu B., Eichbaum Q., Altfeld M., Wherry E. J., Coovadia H. M., Goulder P. J., Klenerman P., Ahmed R., Freeman G. J., Walker B. D. (2006) PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443, 350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dong H., Strome S. E., Salomao D. R., Tamura H., Hirano F., Flies D. B., Roche P. C., Lu J., Zhu G., Tamada K., Lennon V. A., Celis E., Chen L. (2002) Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat. Med. 8, 793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang X., Venet F., Wang Y. L., Lepape A., Yuan Z., Chen Y., Swan R., Kherouf H., Monneret G., Chung C. S., Ayala A. (2009) PD-1 expression by macrophages plays a pathologic role in altering microbial clearance and the innate inflammatory response to sepsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6303–6308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brahmamdam P., Inoue S., Unsinger J., Chang K. C., McDunn J. E., Hotchkiss R. S. (2010) Delayed administration of anti-PD-1 antibody reverses immune dysfunction and improves survival during sepsis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 233–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Y., Zhou Y., Lou J., Li J., Bo L., Zhu K., Wan X., Deng X., Cai Z. (2010) PD-L1 blockade improves survival in experimental sepsis by inhibiting lymphocyte apoptosis and reversing monocyte dysfunction. Crit. Care 14, R220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jin Y., Chauhan S. K., El Annan J., Sage P. T., Sharpe A. H., Dana R. (2011) A novel function for programmed death ligand-1 regulation of angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 1922–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rittirsch D., Huber-Lang M. S., Flierl M. A., Ward P. A. (2009) Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat. Protoc. 4, 31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wesche-Soldato D. E., Chung C. S., Lomas-Neira J., Doughty L. A., Gregory S. H., Ayala A. (2005) In vivo delivery of caspase-8 or Fas siRNA improves the survival of septic mice. Blood 106, 2295–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zellweger R. M., Prestwood T. R., Shresta S. (2010) Enhanced infection of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in a mouse model of antibody-induced severe dengue disease. Cell Host Microbe 7, 128–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katz S. C., Pillarisetty V. G., Bleier J. I., Shah A. B., DeMatteo R. P. (2004) Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are insufficient to activate T cells. J. Immunol. 173, 230–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hotchkiss R. S., Coopersmith C. M., McDunn J. E., Ferguson T. A. (2009) The sepsis seesaw: tilting toward immunosuppression. Nat. Med. 15, 496–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wolfle S. J., Strebovsky J., Bartz H., Sahr A., Arnold C., Kaiser C., Dalpke A. H., Heeg K. (2011) PD-L1 expression on tolerogenic APCs is controlled by STAT-3. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haga S., Terui K., Zhang H. Q., Enosawa S., Ogawa W., Inoue H., Okuyama T., Takeda K., Akira S., Ogino T., Irani K., Ozaki M. (2003) Stat3 protects against Fas-induced liver injury by redox-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 989–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wesche-Soldato D. E., Chung C. S., Gregory S. H., Salazar-Mather T. P., Ayala C. A., Ayala A. (2007) CD8+ T cells promote inflammation and apoptosis in the liver after sepsis: role of Fas-FasL. Am. J. Pathol. 171, 87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lohse A. W., Knolle P. A., Bilo K., Uhrig A., Waldmann C., Ibe M., Schmitt E., Gerken G., Meyer Zum Buschenfelde H. (1996) Antigen-presenting function and B7 expression of murine sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells. Gastroenterology 110, 1175–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ishida Y., Agata Y., Shibahara K., Honjo T. (1992) Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 11, 3887–3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barber D. L., Wherry E. J., Masopust D., Zhu B., Allison J. P., Sharpe A. H., Freeman G. J., Ahmed R. (2006) Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439, 682–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yancopoulos G. D., Davis S., Gale N. W., Rudge J. S., Wiegand S. J., Holash J. (2000) Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature 407, 242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scholzen T., Gerdes J. (2000) The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J. Cell. Physiol. 182, 311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Antoine N., Greimers R., De Roanne C., Kusaka M., Heinen E., Simar L. J., Castronovo V. (1994) AGM-1470, a potent angiogenesis inhibitor, prevents the entry of normal but not transformed endothelial cells into the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cancer Res. 54, 2073–2076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kurniali P. C., O'Gara K., Wang X., Wang L. J., Somasundar P., Falanga V., Espat N. J., Katz S. C. (2012) The effects of sorafenib on liver regeneration in a model of partial hepatectomy. J. Surg. Res. 178, 242–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee S. H., Starkey P. M., Gordon S. (1985) Quantitative analysis of total macrophage content in adult mouse tissues. Immunochemical studies with monoclonal antibody F4/80. J. Exp. Med. 161, 475–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schurich A., Berg M., Stabenow D., Bottcher J., Kern M., Schild H. J., Kurts C., Schuette V., Burgdorf S., Diehl L., Limmer A., Knolle P. A. (2010) Dynamic regulation of CD8 T cell tolerance induction by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 184, 4107–4114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carambia A., Frenzel C., Bruns O. T., Schwinge D., Reimer R., Hohenberg H., Huber S., Tiegs G., Schramm C., Lohse A. W., Herkel J. (2012) Inhibition of inflammatory CD4 T cell activity by murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J. Hepatol. 58, 112–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rodig N., Ryan T., Allen J. A., Pang H., Grabie N., Chernova T., Greenfield E. A., Liang S. C., Sharpe A. H., Lichtman A. H., Freeman G. J. (2003) Endothelial expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 down-regulates CD8+ T cell activation and cytolysis. Eur. J. Immunol. 33, 3117–3126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kassel R., Cruise M. W., Iezzoni J. C., Taylor N. A., Pruett T. L., Hahn Y. S. (2009) Chronically inflamed livers up-regulate expression of inhibitory B7 family members. Hepatology 50, 1625–1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang B. J., Bao J. J., Wang J. Z., Wang Y., Jiang M., Xing M. Y., Zhang W. G., Qi J. Y., Roggendorf M., Lu M. J., Yang D. L. (2011) Immunostaining of PD-1/PD-Ls in liver tissues of patients with hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 17, 3322–3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xie Z., Chen Y., Zhao S., Yang Z., Yao X., Guo S., Yang C., Fei L., Zeng X., Ni B., Wu Y. (2009) Intrahepatic PD-1/PD-L1 up-regulation closely correlates with inflammation and virus replication in patients with chronic HBV infection. Immunol. Invest. 38, 624–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Larrubia J. R., Benito-Martinez S., Miquel J., Calvino M., Sanz-de-Villalobos E., Parra-Cid T. (2009) Costimulatory molecule programmed death-1 in the cytotoxic response during chronic hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 5129–5140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang H. G., Su X., Liu D., Liu W., Yang P., Wang Z., Edwards C. K., Bluethmann H., Mountz J. D., Zhou T. (1999) Induction of specific T cell tolerance by Fas ligand-expressing antigen-presenting cells. J. Immunol. 162, 1423–1430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Askenasy N., Yolcu E. S., Yaniv I., Shirwan H. (2005) Induction of tolerance using Fas ligand: a double-edged immunomodulator. Blood 105, 1396–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van Parijs L., Ibraghimov A., Abbas A. K. (1996) The roles of costimulation and Fas in T cell apoptosis and peripheral tolerance. Immunity 4, 321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wajant H. (2002) The Fas signaling pathway: more than a paradigm. Science 296, 1635–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Keir M. E., Butte M. J., Freeman G. J., Sharpe A. H. (2008) PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26, 677–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uda Y., Hirano T., Son G., Iimuro Y., Uyama N., Yamanaka J., Mori A., Arii S., Fujimoto J. (2013) Angiogenesis is crucial for liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Surgery 153, 70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang L., Wang X., Xie G., Wang L., Hill C. K., DeLeve L. D. (2012) Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell progenitor cells promote liver regeneration in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1567–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yano K., Liaw P. C., Mullington J. M., Shih S. C., Okada H., Bodyak N., Kang P. M., Toltl L., Belikoff B., Buras J., Simms B. T., Mizgerd J. P., Carmeliet P., Karumanchi S. A., Aird W. C. (2006) Vascular endothelial growth factor is an important determinant of sepsis morbidity and mortality. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1447–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iwai Y., Terawaki S., Ikegawa M., Okazaki T., Honjo T. (2003) PD-1 inhibits antiviral immunity at the effector phase in the liver. J. Exp. Med. 198, 39–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang Y., Li J., Lou J., Zhou Y., Bo L., Zhu J., Zhu K., Wan X., Cai Z., Deng X. (2011) Upregulation of programmed death-1 on T cells and programmed death ligand-1 on monocytes in septic shock patients. Crit. Care 15, R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oikawa T., Takahashi H., Ishikawa T., Hokari A., Otsuki N., Azuma M., Zeniya M., Tajiri H. (2007) Intrahepatic expression of the co-stimulatory molecules programmed death-1, and its ligands in autoimmune liver disease. Pathol. Int. 57, 485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu K., Kryczek I., Chen L., Zou W., Welling T. H. (2009) Kupffer cell suppression of CD8+ T cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by B7-H1/programmed death-1 interactions. Cancer Res. 69, 8067–8075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Latchman Y. E., Liang S. C., Wu Y., Chernova T., Sobel R. A., Klemm M., Kuchroo V. K., Freeman G. J., Sharpe A. H. (2004) PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10691–10696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Goyert S. M., Silver J. (2010) Editorial: PD-1, a new target for sepsis treatment: better late than never. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 225–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Loke P., Allison J. P. (2003) PD-L1 and PD-L2 are differentially regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5336–5341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Heymann F., Trautwein C., Tacke F. (2009) Monocytes and macrophages as cellular targets in liver fibrosis. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 8, 307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Karlmark K. R., Weiskirchen R., Zimmermann H. W., Gassler N., Ginhoux F., Weber C., Merad M., Luedde T., Trautwein C., Tacke F. (2009) Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 50, 261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.