Abstract

Heteroleptic copper compounds have been designed and synthesized on solid supports. Chemical redox agents were used to change the oxidation state of the SiO2-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds from Cu(I) to Cu(II) and then back to Cu(I). Optical spectroscopy of a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) suspension demonstrated the reversibility of the Cu(I)/Cu(II) SiO2-immobilized compounds by monitoring the metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) peak at about 450 nm. EPR spectroscopy was used to monitor the isomerization of Cu(I) tetrahedral to Cu(II) square planar. This conformational change corresponds to a 90° rotation of one ligand with respect to the other. Conductive AFM (cAFM) and macroscopic gold electrodes were used to study the electrical properties of a p+ Si-immobilized heteroleptic copper compound where switching between the Cu(I)/Cu(II) states occurred at −0.8 and +2.3 V.

Introduction

State variables represent a class of essential components in the emerging field of nanoelectronic devices1-6 that serve as the physical representations of information used in memory and logic applications.7 Important properties include switching speed, on/off ratio, maximum spatial density, limiting scaling factor, and on/off modulation method. Boolean logic remains the most commonly used information processing methodology in current technology and is based on two discrete states, represented by 1 or 0. A critical first step toward the fabrication of functional nanodevices capable of carrying out Boolean computation is the realization of a physical unit within the device that resides in two stable, distinguishable states. Subsequent integration of this nanostructure into the process of Si-based fabrication technology represents the crucial second step.

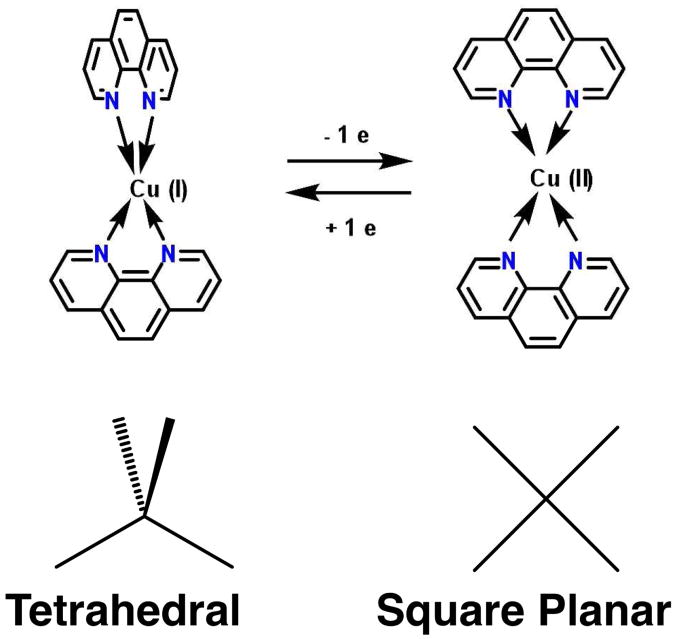

Rotational conformational states of transition-metal-containing compounds constitute a state variable for which information storage relies on physical changes of the molecule. In particular, transition metals offer useful features due to the accessibility of multiple oxidation states (low power consumption). Changes in transition metals include coordination number, color, and geometry.8 Of specific interest here, metal complexes of copper9-18 and nickel19 are known to exhibit oxidation state-dependent geometries. These distinct molecular conformations have potential to be employed as a state variable where the oxidation state of the metal center is used to drive conformational motion such as intramolecular rotation. For example, Cu(I) bis-1,10-phenanthroline compounds are tetrahedral while Cu(II) analogs are square planar (Scheme 1). Similarly, the unique carbons in Ni(III) bisdicarbollide cages adopt a transoid geometry with respect to one another while Ni(IV) analogs adopts a cisoid geometry.20 Such isomerizations can thus be used as a state variable based on a redox-induced intrarotational conformational change. Integration of nickel bisdicarbollides onto a solid silicon support and solid state switching of these systems has yet to be reported. The most highly developed nanoelectrical applications involve organic rotaxanes in a cross bar architecture.21-24

Scheme 1. Cu(I) (tetrahedral) and Cu(II) (square planar) bis-1,10-phenanthroline.

Silicon-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds provide an attractive option as potential physical state variables due to their discrete rotational mechanical movement and robust integration with the Si surface. This one electron redox-induced conformational change is reversible and occurs via the +1 and +2 oxidation states of copper, which isomerizes from the tetrahedral to square planar geometries, respectively (Scheme 1). The redox potential of the copper switch constitutes the minimum energy required for information storage i.e., one electron per molecule at the voltage at which the redox event occurs. Because information storage is based on the nanoscopic movement of atomic nuclei about the copper center, the rate of maximum switching process is fundamentally limited by the frequencies of the relevant rotational vibrational modes of the compound, giving a minimum switching speed on the order of a picosecond.9,25 Molecular integration onto a solid support necessitates a heteroleptic design (a metal center with two different ligands) whereby one ligand serves to immobilize the compound while the second ligand is able to move freely. In this way, a high-density layer of molecular switches can be immobilized onto a bottom electrode (i.e. p+ doped Si) and sandwiched by a top electrode (i.e. macroscopic gold electrodes or a conductive AFM tip) to achieve state variable functionality.25,26

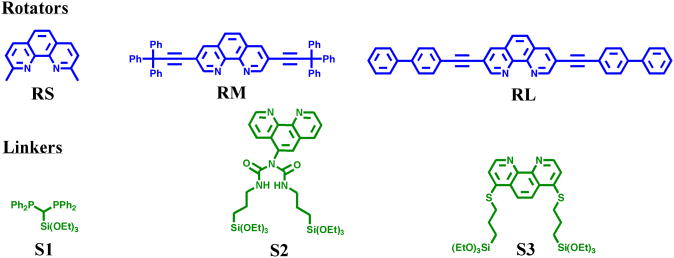

In this work, the design and synthesis of a family of Si-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds is presented. The systems shown undergo reversible, intramolecular conformational motion upon a one-electron oxidation or reduction and represent a physical state variable toward applications in nanoscale logic and memory devices.25,26 This system is particularly attractive due to its relatively low energetic activation barrier (−0.8 and +2.3 V), and potential for high spatial density. Switching between discrete conformation states occurs on the picosecond timescale9,25 and the molecules can be readily integrated into a silicon or silica solid-state platform.25,26 A modular synthetic approach (Scheme 2) enables versatility in the design of size, shape, and function within the nano-architecture of these functionally engineered materials.

Scheme 2. Individual Components of the SiO2-Immobilized Heteroleptic Copper Compounds.

Results and Discussion

Heteroleptic copper compounds in solution undergo fast ligand exchange reactions between copper and bidentate ligands.36,37 Although pure homoleptic copper compounds have been isolated, pure heteroleptic copper compounds in the solid-state are less common.38 The first reported mixed ligand copper systems HETPHEN (HETeroleptic bis(PHENanthroline))39,40 were synthesized via thermodynamic control. An approach used in the past employs bulky aryl substituents at the 2,9- and 4,7-bis(imine) coordination sites where steric bulk and electronic effects selectively control the metal complexation equilibrium through π-π stacking interactions.41 In the reported solution studies, steric and electronic factors governing the selective HETPHEN principles were observed by 1H NMR and ESI-MS titrations.42 Although strategic for locked positions,40,42-52 these interactions prohibit the isomerization of Cu(I) tetrahedral to Cu(II) square planar geometries. For the purpose of using heteroleptic copper compounds as a state variable, at least one ligand needs to be able to rotate freely.

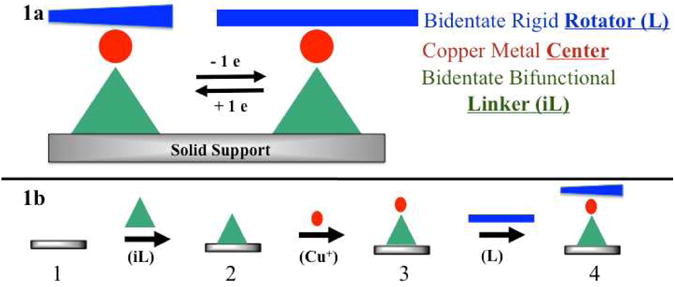

The strategy to synthesize heteroleptic copper compounds with non-hindered ligands that can have a large amplitude rotational conformational change involves a surface outward sequential synthesis.26 The design of heteroleptic copper compounds presented here involves four subunits and includes: (1) a support to serve as a solid-state platform, (2) a bifunctional chelating ligand that is covalently immobilized on the support and can bind to a copper center through bidentate coordination interactions (linker), (3) a Cu(I) or Cu(II) metal center, and (4) a bidentate rigid ligand (rotator). This method begins with an immobilized ligand (iL, linker) on a solid support, with the subsequent addition of copper (Cu+), followed by the chelation of a second ligand (L, rotator), shown by equation 1 and illustrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the copper switch components. (1a) iL is a bidentate bifunctional linker (triangle) that is covalently immobilized on a solid support, a copper ion is the metal center (circle) that is coordinated to both the linker and the rotator, and L is the bidentate rigid rotator (rectangle). Two states are shown, (1a, upper left) Cu(I) tetrahedral and (1a, upper right) Cu(II) square planar. In the Cu(I) system, the ligands are perpendicular to one another while in the Cu(II) system the ligands are parallel to one another. (1b) The surface outward sequential synthesis involves: (1) the solid support, (2) the immobilization of the linker, (3) the addition of the copper center, and (4) the addition of the rotator.

| (1) |

Two classes of bidentate ligands were used as the linker (iL): substituted 1,10-phenanthrolines and bisphosphines. Modified 1,10-phenanthroline ligands are an important class of chelating agents53 and are particularly attractive due to their rigidity, high affinity for metal centers, and ease of modification. Although diimines have one of the highest binding affinities for a copper metal center (e.g. 1,10-phenanthroline: K1 = 7 × 108, K2 = 4 × 106, K3 = 105)54 bisphosphine ligands also form favorable bonds to copper.55

Multiple linker and rotator components that use these types of ligands were designed and synthesized to allow for versatility in the fabrication of nanodevices (Scheme 2). For example, the designs include a short (∼ 1 nm) rotator that can be used for memory in intramolecular vertical conductance measurements25 and long (∼ 2 or 3 nm) rigid rotators with long pi-conjugated arms that can undergo large amplitude motion and function as molecular machines. Along similar lines, immobilized linkers (Scheme 3) with an sp3 center (iS1) or a mono-substituted 1,10-phenanthroline ligand (iS2) allow for flexibility of linker rotation if and when a rotator is prohibited from motion due to the deposition of a top gold electrode via shadow mask evaporation of Si-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds.26 In other words, the relative 90° rotational motion of the linker and rotator, with respect to each other, will cause an overall isomerization of the copper compound. S1 is particularly attractive due to its rigidity in standing up on the surface. Additionally, its phosphorus-containing atoms have high isotopic abundance and hence facilitate in characterization via solid-state NMR. S2 is useful because it is not easily oxidized chemically when switching between the Cu(I) and Cu(II) SiO2-immobilized systems. S3, a di-substituted 1,10-phenanthroline has linkers in the 4,7 positions that allow for a more stationary linker that will not rotate about an sp3 center (a characteristic that is desirable for intermolecular horizontal conductance measurements but not as important for intramolecular conductance measurements).

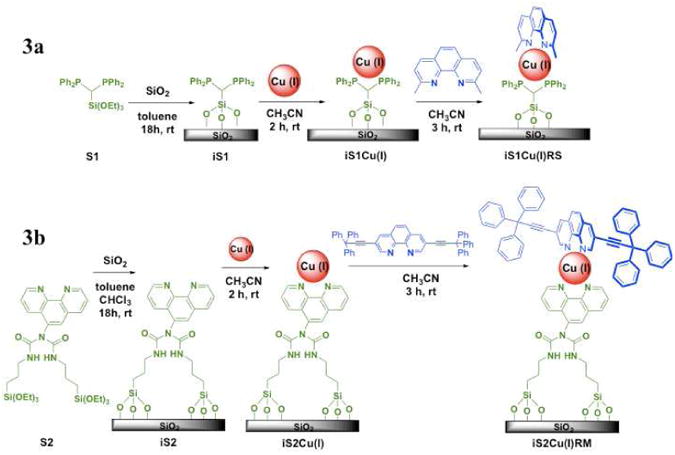

Scheme 3. Surface Outward Sequential Synthesis for Selected Heteroleptic Copper Compounds.

1. Homoleptic Copper Compounds

Homoleptic copper compounds were prepared as model compounds for the solid-state heteroleptic analogues. The homoleptic copper compound, copper bis-3,8-di(ethynyltrityl)-1,10-phenanthroline (Cu(RM)2+) is easily synthesized (Figure S14a). Despite the bulky ethynyltrityl groups present on the 3,8 positions of RM, large amplitude intrarotational motion of the bisRM ligands with respect to one another occurs upon oxidation of Cu(I) to Cu(II). This is further supported by the lack of luminescence in (Cu(RM)2+) and (Cu(RL)2+) as compared to the highly luminescent 2,9-di-substituted aryl groups in homoleptic copper compounds. The luminescence in copper(I) compounds is attributed to the lack of isomerization in Cu(I) to Cu(II) compounds caused by steric bulk.12-14,42,56,57 In order for the phenanthroline ligands to isomerize with the most efficient conformational change, the long rigid π-conjugated substituents (e.g. present in ligands RM and RL) need to be on the 3,8 (not the 2,9) positions of 1,10-phenanthroline.

The reduction potential obtained via cyclic voltammetry for Cu(RM)22+/+ and Cu(RL)22+/+ compared to copper bis-1,10-phenanthroline (Cu(phen)2)2+/+ and copper bis-2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (Cu(RS)2)2+/+ are shown in Table 1.34,57,58 The relatively high Cu(RM)22+/+ and Cu(RL)22+/+ couples compared to the Cu(phen))22+/+ couple can be attributed to the additional electron donating groups provided by the trityl acetylene and 4-ethynyl-biphenyl groups from RM and RL, resepectively.57

Table 1.

Redox Potentials for Cuprous Phenanthroline Derivatives.

| Compound | CuII/I (V) |

|---|---|

| CuI(phen)2+ | 0.54 |

| CuI(RM)2+ | 0.84 |

| CuI(RL)2+ | 0.92 |

| CuI(RS)2+ | 0.99 |

Measured at r.t. in 0.1 M TBAH/CH2Cl2 vs. SCE with ferrocene as an internal standard.

2. Heteroleptic Copper Compounds

A total of six compounds (three linkers and three rotators), shown in Scheme 2, can be used in a modular synthetic approach to synthesize nine combinations of surface-immobilized heteroleptic Cu(I) compounds, (or eighteen total compounds when Cu(II) analogs are included). Each component allows for the versatility of device fabrication and serves useful purposes in the flexibility of the design. Different combinations of linkers and rotators form assemblies with criterion for through molecule conductance (intramolecular) or horizontal conductance (intermolecular) device geometries. In other words, through-molecule-conductance refers to intramolecular conductance from the top ligand, through the metal center to the linker, while horizontal conductance refers to conductance from the pi-conjugated top ligand to neighboring pi-conjugated top ligands.

Silica nanoparticles were chosen as a model solid support because (1) its surface properties mimic the native oxide layer of silicon, (2) linkers can be covalently attached with high surface area, and (3) its high dispersability in dimethyl sulfoxide is extremely practical for optical measurements using UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy. Solid-state NMR, EPR and UV-Vis absorption studies cannot be carried out using p+ Si wafers. The commercially available Merck silica is useful for solid-state NMR and EPR characterization and silica nanoparticles dispersed in liquids are favorable for UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy characterization. Silicon is also a favorable support for the linkers shown in Scheme 2 because alkoxysilanes form strong anchors to the native oxide layer on silicon. Additionally, p+ doped silicon wafers are useful for conductance measurements when a top electrode (macroscopic gold electrodes via shadow mask evaporation or a Pt/Ir AFM tip) is used to complete the device assembly.25,26

Among the linkers that have been immobilized on a silica support, iS127 (Scheme 3a) is attractive due to its short length and phosphorus-containing atoms; that have a high isotopic ratio for NMR and hence allow for the easy detection of surface modified silica particles via solid-state NMR studies. Phosphorus-31 solid-state NMR spectroscopy is a useful tool due to the phosphorus atom's great natural abundance (100 %), large chemical shift dispersion with ½ spin nucleus, and the improvement in the quality of spectra with magic angle spinning (MAS) and cross-polarization (CP) techniques.59 On the other hand, iS228 (Scheme 3b) is attractive due to its robustness against chemical redox agents and the fact that its absorption spectrum does not interfere with the RM π → π* region (Figures S12 and S13). Both iS1 and iS2 have flexibility in rotating when placed in a vertical device geometry due to the sp3 center in iS1 and the mono-substituted 1,10-phenanthroline with an sp3 center in iS2.25 iS3 was designed as a di-substituted 1,10-phenanthroline linker that allows full 90° rotation of the upper ligand since this linker (the bottom ligand) is rigidly immobilized at two points of the molecule. This rigidity is desirable for horizontal conductance measurements in logic applications where alignment is critical.

3. Divergent Synthesis

S1 was immobilized on silica particles to yield the immobilized linker iS1 (Scheme 3a). The 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum for iS1 (Figure S4a) shows two types of carbon peaks associated with iS1. The aromatic region is attributed to the phenyl groups bound to the phosphine. Two peaks appear in the aliphatic region at 59.46 and 16.36 ppm and are attributed to unbound ethoxy60 groups from iS1, from the methylene and methyl carbon atoms of the ethoxy group, respectively. The appearance of these two residual peaks is known because trialkoxysilane reagents do not exclusively form three siloxane bonds upon condensation reaction with silica surface silanol groups: there always exists a distribution of silane species bound by one, two, and three siloxane bonds.60 The 31P CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum for iS1 shows two peaks at 31.38 and −28.30 ppm. The rotational spin of the sample was 10 kHz and corresponding spinning sidebands are observed. The peak at 31.38 ppm is from the formation of a phosphine-oxide with the surface (Figure S4b).59,61 This is confirmed by addition of hydrogen peroxide to iS1 where it is observed that the peak at −28.30 ppm has been oxidized (Figure S4c) to the peak at 31.38 ppm.

S2 was also immobilized on silica and the 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of iS2 (Scheme 3b), shows carbon atom peaks in the carbonyl, aromatic, and aliphatic regions (Figure S5a). Similar to iS1, the 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR of iS2 contains residual alkoxide signals at 59.22 and 16.96 ppm from unbound ethoxy groups. In addition, a methanol wash of iS2 results in a methoxide peak that appears at 50.46 ppm. 29Si CP/MAS solid-state NMR confirms the covalent bonding that forms between S2 and the silica particles (Figure S5b). The peaks corresponding to the various siloxane Qm and organosiloxane Tn species can be identified clearly.62 The Tn bands [Tn = RSi(OSi)nOH3-n, n = 1-3] are resonances of the Si to which the linkers are bonded whereas the Qm bands [Qm = Si(OSi)m(OH)4-m, m = 2-4] correspond to bulk and surface Si to which only oxygen atoms are bonded.

The immobilized ligand, iS3, was produced by the immobilization of S3 on the solid silica support. The 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of iS3 confirms the presence of aromatic and aliphatic carbon atoms (Figure S6a) in addition to the residual ethoxide signals. The 29Si CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum shows the T and Q region of the silicon atoms. The T region shows the binding of one, two and three ethoxy groups to the solid silica support (Figure S6b).

Following the divergent synthetic scheme, subsequent attachment of the metal center and rotator is carried out. In a typical synthesis, copper (I) tetrakis(acetonitrile) hexafluorophosphate was chosen as the starting oxidation state for the copper metal center because of its high solubility in organic solvents such as acetonitrile and methylenechloride. In the case of iS1, starting independently with both Cu(I) and Cu(II) was necessary since the phosphine atoms in iS1 oxidize in the presence of oxidizing agents.59,61 In other words, chemical redox agents cannot be used to demonstrate the reversible two states of the Cu(I) and Cu(II) analogs in the presence of iS1.

The rotators are relatively short (RS, ∼1 nm), medium (RM, ∼2 nm), and long (RL, ∼3 nm) in size. RS is commercially available while RM and RL were synthesized by the Sonogashira coupling of 3,8-dibromo-1,10-phenanthroline to tritylacetylene and 4-ethynyl-biphenyl, respectively.

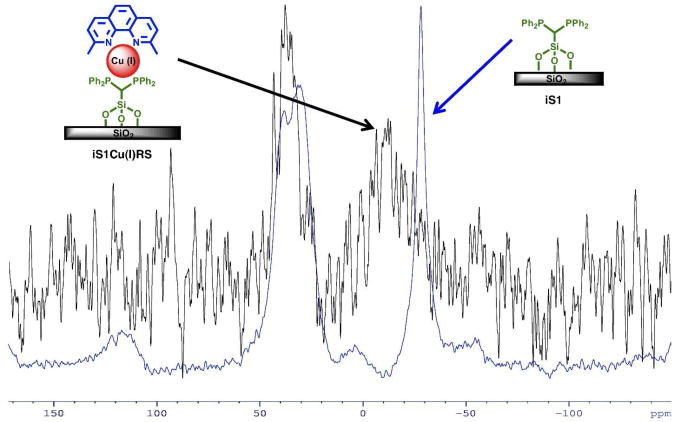

4. Properties of iS1Cu(I)RS

To illustrate the properties of compounds prepared by divergent synthesis and described in the previous section, iS1Cu(I)RS is an example of a compound where the first linker and shortest rotator are examined. Addition of Cu(I) and RS to iS1 yields the compound iS1Cu(I)RS. The 31P CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum for iS1Cu(I)RS shows the shift of the iS1 31P CP/MAS solid-state NMR signal from −28.30 to −12.15 ppm. This confirms the complexation of Cu(I) to iS1 (Figure 2).55 The signal in the 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of the aromatic carbon atoms from the phenanthroline portion of RS overlaps with the aromatic carbon atom signals from the phenyl groups on the phosphorus atoms in iS1. However, the methyl carbons on the 2,9 positions of the phenanthroline ligand of RS are distinctly observed in the 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of iS1Cu(I)RS and appear at 23.81 ppm. Although this signal is broad enough to interfere with the methylene carbon atom in iS1, a comparison of the 13C CP/MAS spectra of iS1 and iS1Cu(I)RS shows the distinction when RS is added to the compound (Figure S9b).

Figure 2.

31P CP/MAS solid-state NMR of iS1 and iS1Cu(I)RS.

Overall, although the number of scans of the iS1Cu(I)RS 13C and 31P CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectra are greater than the iS1 13C and 31P CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectra, the signal to noise for iS1Cu(I)RS is significantly worse. This is a consequence of the presence of a small amount of Cu(II) on the silica surface. The paramagnetic nature of Cu(II) vs Cu(I) significantly decreases the S/N ratio of the spectra (Figure S9a). EPR was used to confirm the presence of Cu(II) on the silica support (Figure S9c). Additionally, UV-Vis absorption spectra of independently synthesized iS1Cu(I)RS and iS1Cu(II)RS show that a metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) band is present for the Cu(I) species, indicative of the tetrahedral geometry. However, no MLCT band is present for the iS1Cu(II)RS implying a different geometry (i.e. square planar) from the Cu(I) form (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

An amount of 2.5 mL of the particle suspension (100 μg/mL) in DMSO of independently synthesized iS1Cu(I)RS and iS1Cu(II)RS. The Cu(I) form has a MLCT around 450 nm but the Cu(II) form does not. The red-curve represents the reduced state while the blue-curve represents the oxidized state.

5. Properties of iS2Cu(I)RS and iS2Cu(I)RM

To illustrate the properties of compounds prepared by divergent synthesis, iS2Cu(I)RS and iS2Cu(I)RM are examples of compounds examined where the second linker is used with either the shortest rotator or medium-length rotator, respectively. The addition of Cu(I) and RS to iS2 produces iS2Cu(I)RS (Scheme 3b). Unlike iS1Cu(I)RS, the methyl groups from the 2,9 position of the phenanthroline ring of RS are not clearly observed in the 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of iS2Cu(I)RS because the signal interferes with the aliphatic carbons of iS2 (Figures S10a and S10b). Therefore, the subsequent addition of Cu(I) and RM to produce iS2RM was used to distinguish between the carbon atom signals of iS2 and RM. The 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of RM shows additional carbon signals that result from the tritylacetylene groups of the phenanthroline ring present on the 3,8 positions of RM. The acetylene group contributes to carbon signals at 99.16 and 81.73 ppm while the trityl carbon results in a carbon atom signal at 56.38 ppm (Figure S7b). Comparison of the 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectra of iS2 and iS2Cu(I)RM shows the addition of RM to iS2 and Cu(I) (Figure S11c). Like iS1Cu(I)RS, the poor S/N ratio in the solid-state NMR spectra of iS2Cu(I)RS and iS2Cu(I)RM shows the presence of paramagnetic Cu(II). This presence is confirmed via EPR (Figures S10c and S11d). It is noteworthy that over time the slow oxidation of Cu(I) to Cu(II) occurs. Therefore, the addition of a reducing agent, such as ascorbic acid, to the immobilized Cu(I) compounds returns air-oxidized Cu(II) centers back to Cu(I).

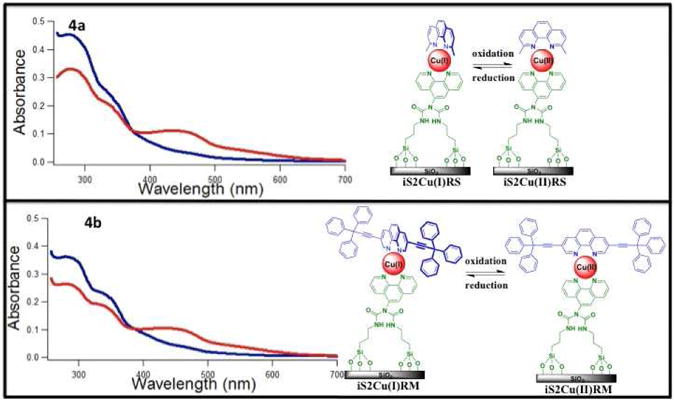

The absorption spectra of added ascorbic acid shows that any remaining Cu(II) was reduced to Cu(I) and hence an increase of the MLCT band at ∼ 450 nm was observed (Figure S11e). UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy was also used to distinguish between iS2Cu(I)RS and iS2Cu(I)RM immobilized on silica nanoparticles and dispersed in DMSO (Figure S11f). iS2Cu(I)RS and iS2Cu(I)RM can be distinguished by the additional shoulder at ∼ 336 nm in the iS2Cu(I)RM spectrum. This peak is attributed to the RM ligand of iS2Cu(I)RM. The UV-Vis absorption of iS2Cu(I)RS and iS2Cu(I)RM is compared to their Cu(II) analogs that were formed by the oxidizing agent, hydrogen peroxide (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

An amount of 2.5 mL of the particle suspension (100 μg/mL) in DMSO of (4a) iS2Cu(I)RS, (4b) iS2Cu(I)RM where the red-curves represent the reduced state. Disappearance of MLCT band of Cu(I) (∼ 450 nm) upon use of an oxidizing agent, H2O2, where the blue-curves represent the oxidized state.

6. Heteroleptic Copper Switches

The switching properties of the SiO2- and p+ Si-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds were studied. The switching characteristics of the SiO2-immobilized systems were explored via chemical redox agents, UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy, and EPR. The p+ Si-immobilized heteroleptic copper switches were studied by two methods: (1) macroscopic gold electrodes25 and (2) a conductive AFM tip.26

7. Heteroleptic Copper Switches on Silica Nanoparticles using Chemical Redox Agents

Tetravalent copper compounds are known to exhibit different geometries based on the charge of the copper metal center and the absence of sterically hindering substituents on the 2,9 positions of 1,10-phenanthroline. More specifically, copper(I) bis-bidentate compounds are tetrahedral while the copper(II) analogs are generally square planar.10,63 Hence up to a 90° rotation of the ligands, with respect to one another, can be achieved via oxidation and reduction of the copper metal center.

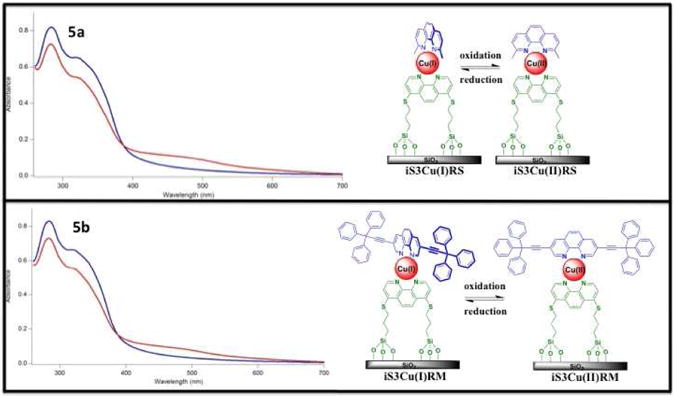

Absorption spectra of iS2Cu(I)RS, iS2Cu(I)RM, iS3Cu(I)RS, and iS3Cu(I)RM were measured by suspending the modified silica nanoparticles in DMSO. The MLCT band in all four samples appears ∼ 450 nm. Upon the addition of hydrogen peroxide and then washing of the particles, all four samples were separately oxidized to Cu(II) compounds. The presence of Cu(II) was observed by the disappearance of the MLCT. These samples were subsequently reduced back to Cu(I) by the addition of ascorbic acid followed by a wash. The MLCT band reappeared upon the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) (Figures S10d, S11e, S12, S13).

EPR characterization is a powerful tool used to determine the structure of paramagnetic compounds, including but not limited to Cu(II) compounds.64,65 Additional data that supports the isomerization of Cu(I) tetrahedral to Cu(II) square planar is extracted by EPR data. To begin with, the bis(1,10-phenanthroline) Cu(I) compounds are known to be tetrahedral66 (Figure S14a) while Cu(II) analogs are square planar.63 Based on the MLCT band at ∼450 nm for the heteroleptic copper compounds discussed above (iS1Cu(II)RS, iS2Cu(II)RS, iS2Cu(II)RM) and the crystal structure from Figure S14a, the SiO2-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds are considered to be tetrahedrally shaped. Upon oxidation of the Cu(I) center, isomerization of Cu(II) square planar takes place and this structural change is confirmed based on the pattern of the EPR signals shown in Figures S9c, S10c, and S11d.64,65

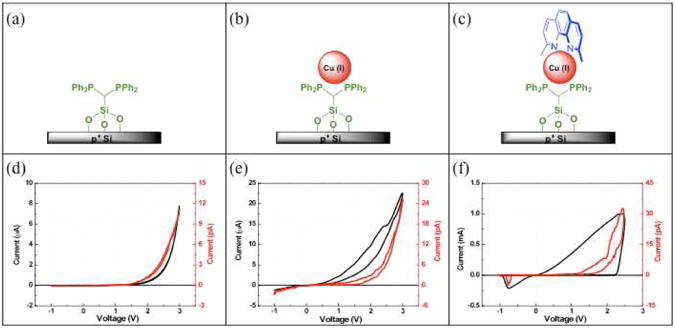

8. Current-Voltage Spectroscopy of iS1, iS1Cu, and iS1CuRS on p+ Si using Two Methods

Characterization of switching events in electrical devices can be readily carried out through I-V spectroscopy. Electrical properties of the immobilized molecular monolayers represented in steps 2-4 of Figure 1b were examined in a sandwich-type device architecture at both the macro- and nanoscale through the use of macroscopic Ti/gold electrodes and localized conductive AFM (cAFM), respectively.1 Discrete switching events are commonly associated with the observation of a distinct increase in conductance above specific threshold voltages in both the positive and negative direction, a persistent ‘ON’ state current following a switching event, and/or a hysteresis within the acquired I-V curve. As seen in Figure 6, I-V characteristics of devices whose molecular layer consisted of solely grafted linkers (iS1), Cu-ligated linkers (iS1Cu) and the fully-formed heteroleptic Cu switch (iS1CuRS) were investigated in order to assess the source of observed solution phase switching events. Beginning with a device residing in the OFF state, denoted by a lack of measured electrical current, bias voltage sweeps were applied to both iS1 and iS1Cu and resulted in the I-V curves seen in Figure 6d and 6e. As expected, neither molecular device revealed any of the effects indicating a molecular switching event described above. The lack of a ligated rigid rotator in these devices serves to eliminate any capability for intramolecular rotational motion. I-V curves acquired on iS1CuRS demonstrated that application of a positive bias >2.2V produced a drastic increase in conductivity that persisted upon sweeping the bias toward a negative potential as seen in Figure 6f. Application of a bias greater than -1V caused the ‘ON’ state to be switched ‘OFF’ and generated a corresponding, abrupt decrease in conductivity that persisted until the positive threshold voltage was applied. In combination, these results indicate that observed switching effects in fully-formed molecular devices are result of conformational effects and do not stem from either the ligand subunits themselves or the interfaces between the ligands and the metal electrodes.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the p+ Si immobilized heteroleptic copper switch components (a-c) and corresponding I-V curves acquired on each component layer in using both macroscopic Ti/Au (black) and Pt-Ir cAFM (red) electrodes (d-f) where molecular switching events are solely evident in the fully-formed compound (f).

Summary

The design and synthesis of a library of silica-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds was reported. The method used to compose this library of heteroleptic compounds involved surface outward sequential synthesis. A modular synthetic approach of three individual components comprised this class of functional materials and included a (1) bidentate linker immobilized on silica, (2) a Cu(I) or Cu(II) metal center and (3) a rigid and bidentate rotator. Solid-state NMR, EPR, and UV-vis absorption spectroscopies were used to characterize these silica-immobilized heteroleptic copper compounds. Hydrogen peroxide and ascorbic acid were used as chemical redox agents to change the oxidation state of the heteroleptic copper compounds from Cu(I) to Cu(II) and then back to Cu(I). Optical spectroscopy of a DMSO suspension demonstrated the reversibility of the Cu(I)/Cu(II) immobilized compounds by monitoring the disappearance and appearance of the MLCT band at 450 nm. EPR spectroscopy confirmed the structure of the SiO2-immobilized Cu(II) species as square planar. The electrical properties of these heteroleptic copper compounds immobilized on p+ Si, using macroscopic gold electrodes25 and conductive AFM26 make these materials promising candidates for future memory and logic applications.

Experimental Section

1. Linkers

[Bis(diphenylphosphino)methyl]triethoxysilane (S1).27

A solution of bis(diphenylphosphino)methane (1.02 g, 2.60 mmol) in 15 mL of toluene was treated with 1.62 mL (2.60 mmol) of 1.6 M n-BuLi in hexane and allowed to stir under an N2 atmosphere at room temperature. After 6 hours, 0.511 mL (2.60 mmol) of chlorotriethoxysilane was added dropwise under rapid stirring. After complete addition the reaction mixture was stirred for an additional 30 minutes. Toluene was removed by vacuum evaporation and the reaction mixture was dissolved in pentane. Centrifugation was used to separate the lithium salt and the supernatant was dried in vacuo to remove the pentane to yield 67% of product (0.824 g, 1.51 mmol). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.99 -7.36 (m, 8 H), 7.09-6.89 (m, 12 H), 3.95 (q, 6H), 2.79 (s, 1H), 1.22 (t, 9H). 31P NMR (202 MHz, C6D6) δ -21.12.

5-N,N-di(amidopropyltriethoxysilane)-1,10-phenanthroline (S2).28

A total of 0.200 g (1.02 mmol) of 5-amino-1,10-phenanthroline was dissolved in 30 mL of CHCl3 and filtered into a reaction flask. The solution was stirred while 1.6 mL (∼ 6.5 mmol) of 3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl isocyanate was added. The chloroform was evaporated at atmospheric pressure and the resulting mixture was heated at 80 °C, under N2, over night. The reaction mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and was then placed in an ice bath. Cold hexanes were added to precipitate an off-white powder. Centrifugation, decanting of the supernatant, and then dissolution of the solid in methanol was carried out. The solution was gravity filtered and the methanol was then removed by rotary evaporation and the final product was dried under vacuum over night to yield 0.274 g, 0.397 mmol (39%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.22 (m, 2H), 8.29 (m, 2H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.71 (m, 2H), 3.70 (q, 12H), 3.23; (m, 4H), 2.10 (br, 2H), 1.60 (m, 4H), 1.13 (t, 18H), 0.53 (m, 4H).

4,7-di(3-(triethoxysilyl)propylthio)-1,10-phenanthroline (S3).29

4,7-dichloro-1,10-phenanthroline (200 mg, 0.803 mmol) was stirred with 20 eq of 3-mercaptopropyl triethoxysilane (4.13 mL16.1 mmol) and 40 eq K2CO3 (4.44 g, 32.1 mmol) (dried in oven over night) in anhydrous THF under N2 for 36 h at 65 °C. The mixture was cooled, centrifuged and the THF from the supernatant was removed under vacuum to give a green oil. Dissolution of the oil in pentane followed by cooling to −115 °C precipitated the final product in a pure form (72% yield, 378 mg, 0.578 mmol). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.56 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 8.55 (s, 2H), 8.12 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 12 H), 2.70 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 1.81 (m, 4H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 18 H), 0.73 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 4H); MS (ESI) calcd for C30H49N2O6S2Si2 [M + H]+ 653.26, found 653.24.

2. Immobilization of Linkers

iS1, iS2, iS3

A total of 0.3 g of silica was slurried in about 50 mL of toluene and excess S1 (3 × 10−4 mol dissolved in 4 mL of toluene), S2 (3 × 10−4 mol, dissolved in 4 mL of CHCl3), or S3 (3 × 10−4 mol dissolved in 4 mL of THF) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h, under N2, at ambient temperature. The reaction mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant was removed. The modified silica particles were washed 3× with toluene and dried over night under vacuum.

3. Rotators

3,8-di(ethynyltrityl)-1,10-phenanthroline (RM)

RM was prepared based on modified procedures.30,31 A mixture of 3,8-dibromo-1,10-phenanthroline32 (0.54 g, 1.60 mmol, 1 eq), 3,3,3-triphenylpropyne33 (2.58 g, 9.60 mmol, 6 eq), dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) (0.071 g, 100 μmol), copper iodide (7.6 mg, 0.400 mmol), and anhydrous triethylamine (3.4 mL) was suspended in anhydrous benzene (20 mL). After refluxing the mixture for 4 d under Ar the solvent was evaporated. The black residue was dissolved in dichloromethane (150 mL), washed with 2% KCN solution (100 mL), water (100 mL), and dried over MgSO4. The residue was purified by column chromatography by first dry loading the crude product with silica, flushing out 3,3,3-triphenylphosphine (hexanes, Rf =1), and then gradually increasing the polarity of the elute (9:1, 6:1, 3:1, 1:1 hexanes/EtOAc respectively, and then EtOAc, Rf = 0.16). The product was recrystallized from EtOAc/hexanes. Yield: 0.890 g (1.25 mmol, 78%); a colorless solid, mp 269 °C. IR (neat) νmax 3086, 3058, 3024, 2218, 1597, 1539, 1490, 1446, 1421 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.24 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 8.36 (d, J = 2.0, 2H), 7.77 (s, 2H), 7.37 – 7.29 (m, 30H); 13C (125 MHz) CP/MAS δ 153, 146, 143, 129, 120, 99, 82, 56; MS (ESI) calcd for C54H37N2 [M + H]+ 713.29, found 713.28.

3,8-di(4-ethynylbiphenyl)-1,10-phenanthroline (RL)

RL was prepared based on modified procedures.30,31 A mixture of 3,8-dibromo-1,10-phenanthroline (0.54 g, 1.60 mmol, 1 eq), 4-ethynylbiphenyl (0.627 g, 3.52 mmol, 2.2 eq), dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) (0.056 g, 0.08 mmol, ∼10%), copper iodide (0.3 g, 0.16 mmol), and anhydrous triethylamine (10 mL) was suspended in anhydrous benzene (20 mL). After refluxing the mixture for 1 d under Ar the solvent was evaporated. The black residue was dissolved in dichloromethane (150 mL), washed with 2% KCN solution (100 mL), water (100 mL) and dried over MgSO4. The residue was purified by column chromatography, by first dry-loading the crude product with silica, flushing out 4-ethynylbiphenyl (SiO2, hexanes, Rf =1) and then gradually increasing the polarity of the elute (9:1, 6:1, 3:1, 1:1 hexanes/EtOAc respectively, EtOAc, and then CHCl3, Rf (10 % MeOH in EtOAc, 0.1 % NEt3 = 0.5). The product was recrystallized from 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane with slow diffusion of ether. Yield: 0.605 g (1.14 mmol, 62%); a pale yellow solid, mp 246-248 °C). IR (neat) νmax 3406, 2920, 2208, 1595, 1522, 1485, 1419 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ 9.28 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 8.81 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (s, 2H) 7.85 – 7.76 (m, 18H). MS (ESI) calcd for C40H25N2 [M + H]+ 533.20, found 533.20.

4. Assembly of SiO2 Immobilized Heteroleptic Cu Compounds

In a typical synthesis, 0.2 g iS1, iS2 or iS3 is slurried in about 30 mL of toluene (see supporting information). A concentration of 2 × 10−4 mol of [Cu(I) (CH3CN)4]PF6 in 4 mL CH3CN was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 2 h, under N2, at ambient temperature. A concentration of 2×10−4 mol of a RS, RM, or RL in 4 mL of CH3CN, CH2Cl2, or tetrachloroethane, respectively (see supporting information) was added to the reaction mixture and was allowed to stir for an additional 3 h. The reaction mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant was removed. The modified silica particles were washed 3× and dried over night under vacuum.

5. Homoleptic Cu Species for Crystallography and Electrochemistry

[Cu(I)bis(3,8-di(ethynyltrityl)-1,10-phenanthroline)]PF6 ([Cu(I)bisRM]PF6)

[Cu(I)bisRM]PF6 was prepared based on a previously reported procedure.34 Two equivalents of RM (7.22 mg, 1 × 10−5 mol) were dissolved in 5 mL of CH2Cl2, and the resultant solution was deaerated with argon. To this solution was added, with stirring, 1.9 mg (5 × 10−6 mol) of Cu(CH3CN)4(PF6) in 3 mL of CH3CN under an argon atmosphere. An orange-red color was immediately observed, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir at ambient temperature for 1 hour. 35 mL of argon-saturated diethyl ether was added to the reaction mixture. After 3 hours, an additional 20 mL of argon-saturated diethyl ether was added to the reaction mixture and allowed to stir overnight under an argon atmosphere. The formed precipitate was filtered onto a glass frit and redissolved in a minimum amount of CH2Cl2. Slow evaporation of diethyl ether produced air-stable crystals of the product in ∼ 88% yield. MS (MALDI) calcd for C108H72CuN4 1488.51, found 1487.98.

[Cu(I)bis(3,8-di(ethynylbiphenyl)-1,10-phenanthroline)]PF6([Cu(I)bisRL]PF6)

Two equivalents of RL (5.33 mg, 1 × 10−5 mol) were dissolved in 5 mL of tetrachloroethane, and the resultant solution was deaerated with argon. To this solution was added, with stirring, 1.9 mg (5 × 10−6 mol) of Cu(CH3CN)4(PF6) in 3 mL of CH3CN under an argon atmosphere. An orange-yellow color was immediately observed, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir at ambient temperature for 1 hour. 35 mL of argon-saturated diethyl ether was added to the reaction mixture and allowed to stir overnight under an argon atmosphere. The formed precipitate was filtered onto a glass frit. 1H NMR (500 MHz, (CD2Cl2) δ 7.89 – 6.79 (m, 46H).

6. UV-Vis Absorption Measurements

Silica nanoparticles were synthesized35 then functionalized by the copper compound (described in supporting information). 2.5 mL of the particle suspension (100 μg/mL) in DMSO was used. Either ascorbic acid or hydrogen peroxide solution was added into the suspension to reduce or oxidize the copper compounds bound on the particle surface, respectively. After the addition of the redox reagent, the particles were washed with and resuspended in DMSO to measure absorbance.

7. Assembly of p+ Si Immobilized Heteroleptic Cu Compounds

A p+ Si wafer was first washed with a piranha solution (1 part 30% H2O2 and 3 parts H2SO4) and then an aqua regia solution (1:3 HNO3:HCl). The wafer was then immersed into a 1×10−5 M solution of iS1 (in toluene), iS2 (CHCl3/toluene), or iS3 (THF/toluene) inside a test-tube. The test-tube was equipped with a stir bar and sealed under an N2 atmosphere. The wafer remained in this stirred solution at ambient temperature, under N2, for approximately 18 h. After washing away excess iS1, iS2 or iS3 with toluene, acetonitrile, or THF, respectively, the modified wafer containing immobilized linkers was subsequently immersed into a test tube containing 1×10−5 M solution of propylaminitriethoxysilane (PTS), equipped with a stir bar, under an N2 atmosphere, at room temperature, for an additional 18 h. The wafer was washed with toluene to remove excess PTS and then placed in a test tube containing 1×10−5 M solution of Cu(I)(CH3CN)4PF6 in CH3CN, under an N2 atmosphere and stirred at ambient temperature for 3 h. A concentration of 1×10−5 M of dmp in CH3CN was added to the reaction test tube and the immersed wafer was allowed to stir under ambient condition and under an N2 atmosphere for an additional 2 h. The wafer was washed thoroughly with CH3CN and dried with a flow of N2 gas and was then placed in a vacuum desiccator over night.

8. Electrical Characterization

Electrical properties of the p+ Si immobilized molecular layers were investigated through current-voltage (I-V) spectroscopy in ambient conditions at both the micro- and nanoscale. First, microscale devices were fabricated by deposition of a Ti/gold film through a shadow mask onto the surface of the molecular layer to form a top electrode. Electrical contact to the device was made using a probe station. Bias voltage sweeps were applied to the top gold electrode with respect to the grounded p+ Si substrate and analyzed by the Keithley 4200 Semiconductor Characterization System. In order to average the non-uniformity of the molecular monolayer, sweep delay and hold times were optimized and resulted in individual measurements requiring 10 min to complete depending on the measured current level. Second, local nanoscale I-V spectroscopic analyses were carried out via conductive atomic force microscopy (cAFM) using the Nanoscope V Dimension Icon (Veeco Instruments). Pt-Ir coated silicon cantilevers (ContPt, NanoWorld) with calibrated spring constants between 0.12-0.15 N/m, first longitudinal resonance frequencies between 11.5-13 kHz, and nominal tip radii of <25 nm were employed in contact mode under a minimum, constant applied load in order to reduce sample perturbation during the measurement. Bias voltage sweeps were applied to the sample with respect to a virtually grounded cAFM probe tip at a rate of 0.25 V/s over the range of interest. Each point within the bias sweep was sampled five times and averaged to enhance the S/N ratio. Presented I-V curves are composed of a single sweep. While small fluctuations attributed to non-uniformity in the active molecular layer were observed between individual devices, I-V characteristics were stable with repeated positive and negative bias sweeps.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

An amount of 2.5 mL of the particle suspension (100 μg/mL) in DMSO of (5a) iS3Cu(I)RS and (5b) iS3Cu(I)RM, where the red-curves represent the reduced state. Disappearance of MLCT band of Cu(I) (∼ 450 nm) upon use of an oxidizing agent, H2O2, where the blue-curves represent the oxidized state. The absorption spectrum of iS3 interferes with the π to π* transition of RM, hence iS3Cu(I)RS and iS3Cu(I)RM absorption spectra cannot be distinguished.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support by the SRC-DARPA Focus Research Program (FCRP) through the Center on Functional Engineered Nano Architechtonics (FENA) and the National Science Foundation through grant CHE0809384. We thank Dr. Bob Taylor, Dr. Bob Schwartz, Dr. Christopher Henry, Dr. Khanhlinh Nguyen, and Dr. Edward Plummer for their helpful discussions and Dr. Yanli Zhao for his help with images. Characterization of this material is supported by shared instrumentation funded by the National Science Foundation and National Center for Research Resources under equipment grant numbers DMR9975975 and S10RR024605, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Spectral characterization data. This material is free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Balzani V, C A, Venturi M. Molecular Devices and Machines - A Journey into the Nano World. 2nd. Weinheim: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Likharev KKJ. Nanoelectron Optoelectron. 2008;3:203–230. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu W, Lieber CM. Nat Mater. 2007;6:841–850. doi: 10.1038/nmat2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pischel U. Austr J Chem. 63:148–164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silvi S, Venturi M, Credi AJ. Mater Chem. 2009;19:2279–2294. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kay ER, Leigh DA, Zerbetto F. Angew Chem Inter Ed. 2007;46:72–191. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galatsis K, Khitun A, Ostroumov R, Wang KL, Dichtel WR, Plummer E, Stoddart JF, Zink JI, Jae Young L, Ya-Hong X, Ki Wook K. IEEE Trans Nanotech. 2009;8:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotton FA. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry. 6th. Wiley; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LX, Shaw GB, Novozhilova I, Liu T, Jennings G, Attenkofer K, Meyer GJ, Coppens P. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7022–7034. doi: 10.1021/ja0294663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MT, Gantzel PK, Karpishin TB. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:2285–2290. doi: 10.1021/ic971164s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruthkosky M, Kelly CA, Castellano FN, Meyer GJ. Coord Chem Rev. 1998;171:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Lv C, Koyama M, Kubo M, Miyamoto A. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, Lv C, Koyama M, Kubo M, Miyamoto A. J Organomet Chem. 2006;691:551–556. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Wang W, Koyama M, Kubo M, Miyamoto A. J Photochem Photobio A: Chem. 2006;179:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 15.He S, Dennis AE, Smith RC. Macromol Rap Commun. 2009;30:2079–2083. doi: 10.1002/marc.200900388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colasson BX, Dietrich-Buchecker C, Jimenez-Molero MC, Sauvage JP. J Phys Org Chem. 2002;15:476–483. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collin JP, Gavina P, Heitz V, Sauvage JP. New J Chem. 1997;21:525. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauvage JP. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:611–619. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawthorne MF, Zink JI, Skelton JM, Bayer MJ, Liu C, Livshits E, Baer R, Neuhauser D. Science. 2004;303:1849–1851. doi: 10.1126/science.1093846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren LF, Hawthorne MF. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:1157–1173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dichtel WR, Heath JR, Stoddart JF. Philosoph Trans Roy Soc a-Mathemat Phys Engin Sci. 2007;365:1607–1625. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2007.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diehl MR, Steuerman DW, Tseng HR, Vignon SA, Star A, Celestre PC, Stoddart JF, Heath JR. ChemPhysChem. 2003;4:1335–1339. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Goddard WA, Jang SS, Dichtel WR, Heath JR, Stoddart JF. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:2136–2143. doi: 10.1021/jp809213m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo Y, Collier CP, Jeppesen JO, Nielsen KA, DeIonno E, Ho G, Perkins J, Tseng HR, Yamamoto T, Stoddart JF, Heath JR. ChemPhysChem. 2002;3:519. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20020617)3:6<519::AID-CPHC519>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue M, Kabehie S, Stieg AZ, Tkatchouk E, Benitez D, Stephenson RM, Goddard WA, Zink JI, Wang KL. App Phys Lett. 2009;95:093503–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabehie S, Stieg AZ, Xue M, Liong M, Wang KL, Zink JI. J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1:589–593. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piestert F, Fetouaki R, Bogza M, Oeser T, Blümel J. Chem Commun. 2005:1481–1483. doi: 10.1039/b413642j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kloster GM, Watton SP. Inorg Chim Acta. 2000;297:156–161. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terry TJ, Stack TDP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4945–4953. doi: 10.1021/ja0742030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmittel M, Michel C, Wiegrefe A. Synthesis. 2005;2005:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Tet Lett. 1975;16:4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitoh Y, Koizumi Ta, Osakada K, Yamamoto T. Can J Chem. 1997;75:1336–1339. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominguez Z, Dang H, Strouse MJ, Garcia-Garibay MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7719–7727. doi: 10.1021/ja025753v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruthkosky M, Castellano FN, Meyer GJ. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:6406–6412. doi: 10.1021/ic960503z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai Q, Luo ZS, Pang WQ, Fan YW, Chen XH, Cui FZ. Chem Mater. 2001;13:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigel H, Huber PR, Griesser R, Prijs B. Inorg Chem. 1973;12:1198–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigel H. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1975;14:394–402. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan J, Bats JW, Schmittel M. Inorganic Chemistry. 2009;48:6338–6340. doi: 10.1021/ic9008366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmittel M, Ganz A. Chem Commun. 1997:999–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmittel M, M C, Liu SX, Schildbach D, Fenske D. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2001:1155–1166. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malini-Balakrishnan R, Scheller KH, Haering UK, Tribolet R, Sigel H. Inorg Chem. 1985;24:2067–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalsani V, Schmittel M, Listorti A, Accorsi G, Armaroli N. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:2061–2067. doi: 10.1021/ic051828v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halper SR, Cohen SM. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:4139–4141. doi: 10.1021/ic0504442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halper SR, Malachowski MR, Delaney HM, Cohen SM. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:1242–1249. doi: 10.1021/ic0352295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Listorti A, Accorsi G, Rio Y, Armaroli N, Moudam O, Gegout A, Delavaux-Nicot B, Holler M, Nierengarten JFO. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:6254–6261. doi: 10.1021/ic800315e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller MT, Gantzel PK, Karpishin TB. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4292–4293. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pogozhev D, Baudron SA, Hosseini MW. Inorg Chem. 2009;49:331–338. doi: 10.1021/ic902057d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmittel M, Michel C, Wiegrefe A, Kalsani V. Synthesis. 2001;10:1561. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stange AF, Wolfgang KZ. Anorg Allg Chem. 1996;622:1118–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cuttell DG, Kuang SM, Fanwick PE, McMillin DR, Walton RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6–7. doi: 10.1021/ja012247h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin L, Zhang QS, Sun W, Wang JY, Lu CZ, Cheng YX, Wang LX. Dalton Trans. 2009:9388–9391. doi: 10.1039/b916782j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang QS, Ding JQ, Cheng YX, Wang LX, Xie ZY, Jing XB, Wang FS. Adv Funct Mater. 2007;17:2983–2990. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sammes PG, Yahioglu G. Chem Soc Rev. 1994;5:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jorgensen CK. Inorganic Complexes. Vol. 1 Academic Press Inc.; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Black JR, Levason W, Spicer MD, Webster M. J Chem Soc Dal Trans. 1993:3129–3136. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dietrich-Buchecker CO, Marnot PA, Sauvage JP, Kirchoff JR, McMillin D. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1983:513–515. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eggleston MK, McMillin DR, Koenig KS, Pallenberg A. J Inorg Chem. 1997;36:172–176. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scaltrito DV, Thompson DW, O'Callaghan JA, Meyer GJ. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;208:243–266. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blümel J. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:5050–5056. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blümel J. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:2112–2113. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sommer J, Yang Y, Rambow D, Blümel J. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7561–7563. doi: 10.1021/ic049065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peng C, Zhang H, Yu J, Meng Q, Fu L, Li H, Sun L, Guo X. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:15278–15287. doi: 10.1021/jp051984n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amournjarusiri K, Hathaway BJ. Acta Crystallograph Sec C. 1991;47:1383–1385. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zink JI, Drago RS. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:4550–4554. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hyde JS, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Basosi R, Froncisz W, Antholine WE. J Magnet Res (1969) 1989;82:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pallenberg AJ, Marschner TM, Barnhart DM. Polyhedron. 1997;16:2711–2719. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.