Abstract

Peptide-triazole (PT) entry inhibitors prevent HIV-1 infection by blocking viral gp120 binding to both HIV-1 receptor and coreceptor on target cells. Here, we used all-atom explicit solvent molecular dynamics (MD) to propose a model for the encounter complex of the peptide-triazoles with gp120. Saturation Transfer Difference NMR (STD NMR) and single-site mutagenesis experiments were performed to test the simulation results. We found that docking of the peptide to a conserved patch of residues lining the “F43 pocket” of gp120 in a bridging sheet naïve gp120 conformation of the glycoprotein, led to a stable complex. This pose prevents formation of the bridging sheet minidomain, which is required for receptor/coreceptor binding, providing a mechanistic basis for dual-site antagonism of this class of inhibitors. Burial of the peptide triazole at gp120 inner/outer domain interface significantly contributed to complex stability and rationalizes the significant contribution of hydrophobic triazole groups to peptide potency. Both the simulation model and STD NMR experiments suggest that the I-X-W (where X=(2S, 4S)-4-(4-phenyl-1H-1, 2, 3-triazol-1-yl) pyrrolidine) tripartite hydrophobic motif in the peptide is the major contributor of contacts at the gp120/PT interface. Since the model predicts that the peptide Trp side chain hydrogen bonding with gp120 S375 contributes to stability of the PT/gp120 complex, we tested this prediction through analysis of peptide binding to gp120 mutant S375A. The results showed that a peptide triazole KR21 inhibits S375A with 20-fold less potency versus WT, consistent with predictions of the model. Overall, the PT/gp120 model provides a starting point for both rational design of higher affinity peptide triazoles and development of structure-minimized entry inhibitors that can trap gp120 into an inactive conformation and prevent infection.

The envelope glycoprotein spikes on the HIV surface are the receptor recognition machinery of the virus, responsible for initiation of host cell entry (1, 2). Each envelope spike is a trimer of non-covalent dimers of transmembrane gp41 and the highly glycosylated gp120 (2). Viral entry occurs as a sequence of interactions with cell surface receptors: gp120 binds the CD4 receptor resulting in a conformational change which decrypts an epitope on gp120 that binds the coreceptor, a member of the chemokine receptor family, usually CCR5 or CXCR4 (2, 3). Binding to the coreceptor results in exposure of the gp41 fusion peptide, its insertion into the target membrane, and subsequent formation of the “six-helix bundle” of gp41 which likely drives fusion of the target cell and viral membranes, allowing the viral capsid to enter the cell (4, 5).

The multi-step process of viral entry provides a series of targets for intervention and blocking infection before the virus establishes a foothold in the host (6). Enfuvirtide (T20) is a subcutaneously injected 36 amino acid peptide that binds to the transiently exposed HR1 of gp41 and prevents formation of the six-helix bundle, preventing viral entry (7). It was approved for clinical use in 2003, although its low bioavailability and poor pharmacokinetics have spurred research for its improvement (8). Maraviroc, an orally administered small molecule that binds to CCR5 and inhibits gp120 recognition, was approved by the FDA in 2007 (7). Emergence of X4-tropic or R5X4-dualtropic viruses utilizing CXCR4 are the most common pathways of resistance to maraviroc (6, 9). The success of combination therapy has shown the value of using multiple agents to target sequentially diverse HIV (8). Prominent examples of targeting gp120 through inhibiting its interactions with CD4 or CCR5/CXCR4 include: NBD-556/DMJ-II-228 which inhibit gp120/CD4 interaction and BMS378806/BMS488043 which prevent viral entry through an unknown mechanism involving conformational changes in the envelope spike (10-12). The former is an agonist of coreceptor binding (13), although very recent work has shown that this undesirable phenotype can be eliminated by structural modification (14). The BMS class has a very small barrier to resistance as 1-2 mutations in gp120 result in 40-500 fold resistance to the inhibitor (7).

12p1 is a small peptide (with the sequence RINNIPWSEAMM) that allosterically inhibits gp120 interactions with both the receptor and the coreceptor (15, 16). Replacing the middle proline with azidoproline and derivatizing the latter with various alkynes through click chemistry led to identification of triazole variants with an approximately 400 fold increase in potency, generating a new class of peptide triazole (PT) entry inhibitors with low nanomolar affinity for gp120 (17, 18). HNG-156, which contains a ferrocenyl triazole-substitution, binds to gp120 with an equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of 7 nM, compared to the 5400 nM KD of 12p1 (19). It antagonizes gp120 interactions with both CD4 and coreceptor and inhibits HIV-1BaL entry at nanomolar 50% effective concentrations (EC50). This class of entry inhibitors is broadly active against various HIV clades, nontoxic and can be synergistically combined with other entry inhibitors (20, 21). Recently, it was found that some variants of the peptide can disrupt the viral membrane, leading to cell-free HIV virolysis and inactivation (22). Gp120 shedding and virolysis were shown to be dependent on the specific interactions of the peptides with gp120 (22). Clearly such peptide triazoles hold great promise for both therapeutic and microbicidal applications. Understanding the binding mode of peptide triazoles in the context of gp120 structure would help greatly in further developing peptide designs with improved potency and peptidomimetic character.

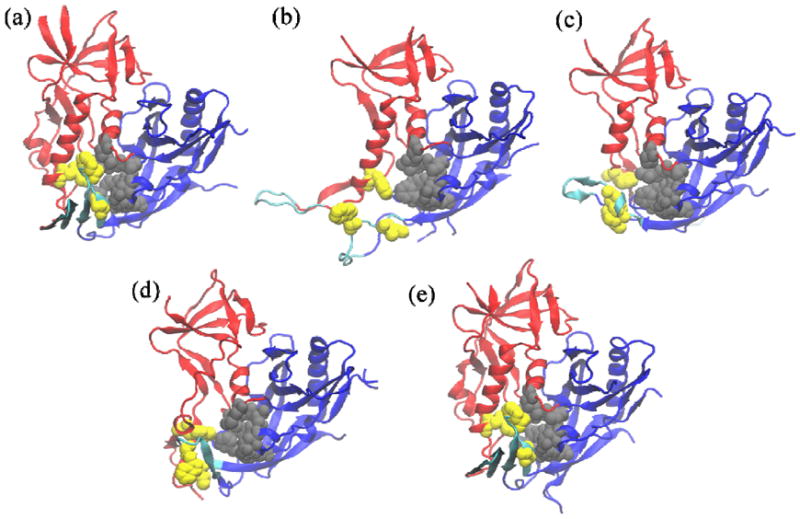

The crystal structure of deglycosylated HIV gp120 lacking the V1/V2/V3 variable loops (gp120 core) in complex with soluble CD4 and a coreceptor surrogate antibody (mAb 48d) shows gp120 in its canonical activated state (Figure 1a) (23). In the simplest interpretation, gp120 in this conformation can be divided into the inner domain, the outer domain and, at their interface; a four strand β-sheet (composed of β2, β3, β20 and β21) called the bridging sheet. The latter is where the coreceptor binds (24, 24). At the intersection of inner and outer domains with the bridging sheet lies a deep cavity called the “F43 pocket”. Residues lining this cavity are hydrophobic, well conserved and thought to be important for gp120 function (24). Out of 23 crystal structures of various HIV gp120 cores available in the protein data bank (PDB), only a handful are resolved in a conformation significantly different than the activated state (25). These include the mAb F105-bound (Figure 1b) (26), the mAb b13-bound (Figure 1c) (26) and the mAb b12-bound (Figure 1d) (27) conformations, all of which show a structure without a bridging sheet. Very recent studies suggest that the core gp120 has a propensity to more frequently sample the activated state with a folded bridging sheet (Figure 1e) (25), while the same study suggests that the full-length gp120 monomer and the native-state spike-bound gp120 are flexible, conformationally diverse and not in an activated state (25). The latter is in line with previous findings suggesting conformational diversity as a mechanism of viral evasion (28, 29). It has been proposed that peptide triazoles inhibit gp120 interactions with CD4 and the coreceptor surrogate, mAb 17b, by trapping the flexible ground state viral protein in one or more inactive conformations (15, 16, 30) and possibly preventing bridging sheet formation (16).

Figure 1.

conformations of gp120 core that have been crystallographically resolved to date: (a) unliganded (b) F105-bound (c) b13-bound (d) b12- and (e) CD4/48d-bound. The structures (d) and (e) were resolved using highly engineered and disulfide-stitched gp120 sequences. The sequence used in (e) contained the pocket filling S375W/T257S mutations. Inner domain is shown in red, outer domain in blue and components of the bridging sheet in cyan. Gray color depicts the outer domain residues of the F43 pocket (V255, T257, E370, F382, Y384, M475, S256bb, S375bb, F376bb and N377bb where the bb suffix indicates backbone atoms), which are conformationally invariant between different structures. yellow depicts the inner domain (W112) or β20/β21 (W427, I424, N425bb) members of the pocket.

Currently there are no crystal structures of a peptide triazole/gp120 complex, hampering efforts to optimize the peptide potency and develop non-natural peptidomimetics through structure-based design. The only direct study aimed at identifying binding determinants on the peptide employed saturation transfer difference NMR (STD NMR) to investigate binding of the parent 12p1 peptide to gp120. Those results showed that the bulky hydrophobic sidechain of peptide tryptophan binds to gp120 (31) consistent with previous synthetic variation studies on the peptide sequence (15-17). However, neither a mechanistic explanation of the interaction nor a model of the complex was suggested. Binding of peptide triazoles to full-length gp120 is characterized by a smaller negative entropy change (-TΔS ≅ +6.3 kcal.mol-1) (30) compared to CD4/gp120 binding (-TΔS=44.2 kcal.mol-1) (28), suggesting that gp120 maintains substantial conformational flexibility when bound to the peptide. This might be one of the reasons the gp120/peptide complex has resisted crystallization efforts to date. In this work, we set out to build atomistic models of gp120/peptide triazole complexes. We hypothesized that the peptide binds to a large hydrophobic cavity on the glycoprotein which is exposed in bridging-sheet naïve conformations of gp120, like the mAb F105-bound conformation. We used all-atom, explicit-solvent molecular dynamics to populate various conformations of an encounter complex consistent with this hypothesis. The most stable and energetically favorable complex showed a specific orientation of the peptide with its tryptophan inside the F43 pocket and its isoleucine plugging a shallow cavity at the junction of the inner/outer domain. This remarkably stable pose was reached after backbone movements of the β20/β21 loop which buried the large phenyl-triazole appendage on the derivatized proline. Independently, we used saturation transfer difference NMR (STD NMR) to study the peptide residues that come into contact with gp120 using a less potent version of the peptide. These results are in good agreement with the simulation model and show that the hydrophobic core of the peptide provides the major contact surface for gp120 interaction. In addition, the peptide/protein interface from the model encompasses all the residues which were found in a parallel study to be important for peptide binding to gp120 (32). Finally, we tested the predictive utility of the model by modifying a PT/gp120 contact which was found to be important in the simulations, and verified this prediction experimentally. Altogether, these findings provide a working model for the mechanism of dual inhibition of peptide-triazoles and can help both to design peptides with improved potencies and guide efforts to produce a stabilized complex for future crystallographic analysis.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis

Peptide triazoles (Table 1) were synthesized via manual solid-phase synthesis using Fmoc chemistry on a Rink amide resin at 0.25 mmol scale, purified using reverse phase HPLC and validated by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) as detailed elsewhere (30).

Table 1.

Sequence and functional properties of parent 12p1 and peptide triazole variants. Cit in the peptide sequence denotes citrulline.

| Designation | Sequence | Triazole Derivative | Chirality | IC50(ELISA) [nM][a] | IC50(SPR) [nM][b] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp Cα | Pro Cγ | sCD4 | mAb 17b | sCD4 | mAb 17b | ||||

| UM101[c] | Cit1-N2-N3-I4-X5-W6-S7 | Phenyl | S | S | 230 | 670 | - | - | |

| UM25 | Cit1-N2-N3-I4-X5-W6-S7 | para-aminophenyl | S | S | 1100 | 18000 | - | - | |

| UM25RS | Cit1-N2-N3-I4-X5-W6-S7 | para-aminophenyl | S | R | >1E+5 | >1E+5 | - | - | |

| UM25RR | Cit1-N2-N3-I4-X5-W6-S7 | para-aminophenyl | R | R | >1E+5 | >1E+5 | - | - | |

| UM25SR | Cit1-N2-N3-I4-X5-W6-S7 | para-aminophenyl | R | S | >1E+5 | >1E+5 | - | - | |

| 12p1 | R1-I2-N3-N4-I5-P6-W7-S8-E9-A10-M11-M12 | - | S | - | - | - | 1100 | 1600 | |

| HNG156 | R1-I2-N3-N4-I5-X6-W7-S8-E9-A10-M11-M12 | Ferrocenyl | S | S | - | - | 112 | 152 | |

| UM24 | Cit1-N2-N3-I4-X5-W6-S7 | Ferrocenyl | S | S | - | - | 118 | 138 | |

| KR21 | R1-I2-N3-N4-I5-X6-W7-βA8[d]-BtLys9[e]-G10 | Ferrocenyl | S | S | 16.4 | 80 | 85 | 110 | |

IC50 determined using ELISA as outlined in Materials and Methods.

From references (19) and (30); IC50 was determined using SPR and values are shown here for comparison.

X in the sequence denotes derivatized azidoproline.

βA denotes β-alanine.

BtLys denotes Ne-biotinyl-L-lysine.

From reference (32)

Protein production

Monoclonal antibody 17b was obtained from Strategic BioSolutions. Soluble CD4 (sCD4) and Full-length HIV-1YU2 gp120 and were produced and purified as described before (30). The S375A mutation was produced and purified as reported previously (32). Briefly, DNA for transient transfection was purified using the Qiagen MaxiPrep kit (Qiagene) and transfected into confluent HEK 293F cells according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Five days later, cells were harvested, spun down and the supernatant was filtered through 0.2 μm filters. Purification was performed using nickel affinity chromatography as described earlier (33), followed by size-exclusion on a Hiload 26/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in order to separate gp120 aggregates from monomers. Size and purity of the final product was verified by separation on 7.5% acrylamide non-reducing SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomasie blue.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) kinetic interaction analysis experiments were performed on a Biacore 3000 (GE) machine. Gp120 (WT and S375A) was immobilized on a CM5 chip using standard NHS/amine conjugation. Anti IL5α-receptor mAb 2B6R was immobilized to 2000 RUs on one chip flow cell for use as a control surface. For direct binding experiments of KR21 peptide or sCD4 to gp120, analytes were injected at 100 μL/min for 2.5 minutes, followed by 5 minutes dissociation. Surfaces were regenerated using 3 seconds of 10 mM HCl injection. All experiments were done in filtered and degassed PBS with 0.005% Tween-20 and 0.1 % Sodium Azide, pH 7.2, at 25°C. For KR21/sCD4 competition experiments, serial dilutions of peptide with constant concentrations of sCD4 (50 nM) were injected over the gp120 surface. Data were fit to the Langmuir 1:1 binding equation to estimate steady state affinity in Biaevaluation 4.1 (direct binding), or to a 4-parameter sigmoidal (competition) in Origin 7.0 (OriginLab).

Saturation transfer difference (STD) NMR

All NMR data were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker Avance 600 NMR equipped with a cryogenically cooled z-shielded gradient probe. Series of 1D STD spectra were acquired with selective irradiation at -1.5, 11 and 12 ppm for on-resonance spectra, and 30 ppm for off resonance ‘reference’ spectra, using a train of 50 ms Gaussian-shaped radio frequency pulses separated by 1 ms delays and an optimized power level of 55 db. Water suppression was achieved using excitation sculpting (34) 1H and 13C chemical shift assignments were made by interpreting COSY, HOHAHA and NOESY spectra of the free peptides in solution. Samples were prepared in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 50 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA at a final concentration of 15 μM gp120 and 1.2 mM peptide. The pH of each sample was adjusted to 6.85 with 0.5 mM NaOH or HCl (not corrected for 2H). The NMR data were processed and analyzed with Topspin 2.1.6; in particular, each on-resonance spectrum was subtracted from its corresponding off-resonance spectrum to give a difference spectrum that was phase corrected using Topspin 2.1.6. Relative STD enhancements were determined by integrating peak intensities and normalizing to peak/s showing the largest enhancement (here Trp indole protons). To assure that artifacts were not introduced with protein irradiation, enhancements for spectra recorded with the above three different on-resonance carrier frequencies were compared. Though no STD signals were observed in control spectra using the same pulse sequence in the absence of protein, slight differences (<5%) in enhancements were observed. We therefore chose to integrate the upfield signals in spectra irradiated at 12 ppm, and the aromatic signals in spectra irradiated at -1.5 ppm.

Molecular simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using NAMD 2.7 (35) and the CHARRM22 force field (36). CHARMM parameters for the triazole appendage on the peptide were estimated by similarity to those available in the CHARMM general force field (37), using ParamChem online tool v0.9.19 (https://www.paramchem.org/) (38, 39) and, if necessary, manual addition of missing parameters (supporting information). Initial coordinates of HIV-1 YU2 gp120 core in complex with the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of antibody F105 were extracted from PDB entry 3HI1 (26). Missing residues (V4 loop and the base of V3 loop) were modeled in silico as unstructured loops. Hereafter, we will refer to this system as the “F105-bound” state. All structural manipulations and image rendering were done in VMD (40).

For a typical system setup for MD runs, the polypeptide was solvated in a TIP3P (41) water box with at least 20 Ȧ distance between the polypeptide molecule and the periodic box boundary. Neutralizing Na+ and Cl- ions were added to a total NaCl concentration of 0.025 M. A 2 femtosecond time-step was used in all integrations. The system temperature was kept constant at 310 K by coupling all non-hydrogen atoms to a Langevin thermostat with a friction coefficient of 5 ps-1. Nonbonded interactions were cut off above 9 Ȧ and smoothed to zero beginning from 8 Ȧ. PME long-range electrostatics with a grid spacing of 1 Ȧ was used, and all bonds involving hydrogens were constrained using RATTLE (42). Equilibration runs were performed at constant volume (NVT ensemble).

We used the F105-bound state directly from the crystal structure (3HI1) as the target for docking studies. UM101 or UM25 were minimized for 20 ps and equilibrated for 20 ns to sample conformations for initial complex pose generation. The minimized conformation of UM25 was manually oriented close to the F43 pocket of the F105-bound gp120 from the crystal structure (PDB 3HI1). In this latter state, the F43 pocket is open and exposed, with only the outer domain wall of the pocket formed such that the peptide tryptophan is located close to the F43 pocket and the peptide isoleucine is at the inner-outer domain interface. Twenty (20) conformations were randomly selected from the UM25 equilibration run and aligned over this initial conformation using the heavy atoms of these two peptide residues. For UM101 initial poses, the same initial conformations were used, replacing the para-amino group on the triazole with hydrogen. Water and neutralizing ions were added to these initial conformations (as explained above), and the system was minimized for 40 ps, keeping all protein non-hydrogen atoms fixed to relieve protein/peptide clashes. An additional 20 ps minimization was performed allowing for movement of the protein atoms. After manually inspecting all runs to check for any remaining clashes, runs with no overlaps were submitted for 15 ns of free MD equilibration. This resulted in 165 and 225 ns of MD simulation for UM101 and UM25 complexes, respectively.

For each peptide, the MD-generated systems were sampled every 100 ps and pooled. After orienting the conformations over the gp120 outer domain, coordinates of the peptide heavy atoms were extracted and clustered using the following procedure. Each peptide conformation represents a point in a 3N-dimensional space of Cartesian coordinates, where N is the number of atoms considered for analysis. We first performed standard k-means clustering on the set of f data points extracted from the trajectory, for 2 ≤ k ≤ 50. The task was then to find k for which the set of cluster centers most efficiently described the complete dataset, which we termed k*. We opted to use similarity between the ordered eigenvectors of the global covariance matrix Cαβ and those of the covariance matrix computed from among the k-means . The rationale was that, because covariance matrix eigenvectors defined directions in Cartesian space along which the data was most variable, the mean values (cluster centers) whose covariance matrix eigenvectors best recapitulated these most highly variable directions of the global data set were themselves the most efficient “coarse-graining” of the dataset. We used the following rule: k* is that k for which the dot-products of the k−1 eigenvalue-descending ordered eigenvectors of the covariance matrix computed using the k-means with their respective eigenvectors of the global covariance matrix are all greater than 0.5, and such that this number of “near-parallel” eigenvectors of the global and k-mean covariance matrices is at least equal to the number of global eigenvectors which account for at least 80% of the variance in the global data. The amount of the global variance accounted for by each principal component (PC) is equal to the variance of that PC divided by the total dataset variance (43). Since the k-means algorithm is sensitive to the choice of the initial cluster seeds (44), the whole loop was repeated 50 times and the result which gave the most well-packed clusters (as measured by the sum of Euclidean distances of cluster members from the cluster center) was used as the global optimum. All data points were transformed to standard z-scores before analysis. All analyses were done in MATLAB (MathWorks). Protein–peptide interaction energy was measured in NAMD as the non-bonded (van der Waals and electrostatic) part of CHARMM energy between the two molecules, in absence of water and under a dielectric constant of 80. We here report the root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of peptide atoms averaged for all member conformations of a cluster as a metric of cluster uniformity and stability. The average non-bonded interaction energy (hereafter referred to as interaction energy or simply energy) and average peptide RMSD of each cluster were used as the principal scoring metrics. The internal energy of the protein or the peptide were not included in the scoring as the former would have swamped and smoothed out any differences in the interaction energy, and both were found to be fairly constant throughout all simulations.

We submitted the F105-bound gp120 conformation from PDB 3HI1, along with an initial peptide conformation, to the SwissDock server (http://swissdock.vital-it.ch/) (45). SwissDock is a free service which automates the pocket detection, pose generation and scoring process. We used this service as an unbiased method for generation of PT/gp120 encounter complexes. The scoring was based on a combination of contributions from CHARMM energy terms and surface desolvation terms (46). The top highest ranking results from the web server were selected and the top five which were more than 1 Ȧ different in peptide RMSD submitted for explicit-solvent all-atom MD runs, clustered and analyzed the same way as the two production sets explained above.

Results

Choice and characterization of peptide triazoles used in modeling and studies

Most of our past work on PTs have used peptides containing a ferrocenyl group on the triazole appendage (Table 1). Although this was found to lead to the most potent peptides, a phenyl moiety on the triazole leads to almost equally potent peptides (19). We chose to use phenyl-containing triazoles for our modeling and NMR studies as we can use available CHARMM parameters for the phenyl and our most diverse structure-activity studies on the triazole were done on a phenyl scaffold (17). To facilitate STD NMR studies of peptide triazole interactions with gp120, it was necessary to select peptide constructs that bound gp120 with sufficiently low affinity, since the efficiency of saturation transfer to the ligand depends on its off-rate from the protein (47). Thus, we introduced a para-amino group on the phenyl triazole which based on past work, was expected to decrease the peptide affinity for gp120 (17) and increase solubility.

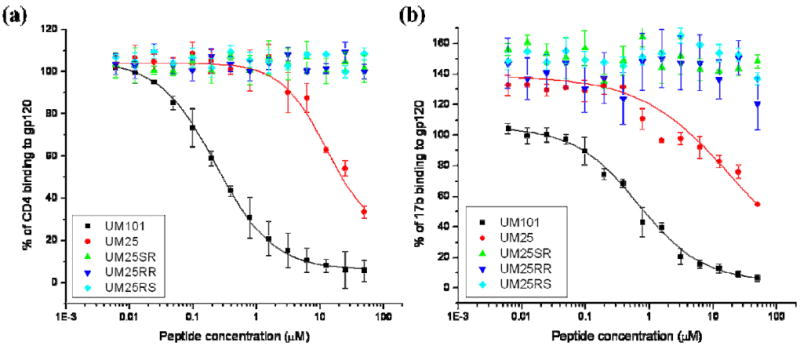

We used competition ELISA to measure the peptide triazole effects on gp120 interactions with sCD4 and 17b. The results are shown in Figure 2. Mean inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were calculated after fitting the data to a logistic function in Origin (OriginLab) and are reported in Table 1. Replacing the ferrocenyl triazole of HNG156 with phenyl triazole in UM101 results in a decrease in 17b-inhibitory potency and a similar but smaller effect on sCD4-inhibitory potency (Table 1) (17, 19). Changing the phenyl triazole of UM101 to para-aminophenyl triazole in UM25 has a much stronger negative effect on the peptide potency and almost reverts the sCD4 IC50 to that of the parent peptide 12p1 with no triazole. 17b inhibitory potency is almost lost and an approximate IC50 value of 18 μM can be estimated from the dose response in Figure 2. These results are in line with previous findings on the correlation of the triazole derivative hydrophobicity and peptide affinity, with the more hydrophobic and bulky derivatives producing more potent inhibitors (17).

Figure 2.

Effect of peptide triazoles on HIV-1YU2 gp120 interaction with (a) sCD4 and (b) 17b. IC50 values were determined by fitting the UM101 and UM25 data to a logistic function in Origin (OriginLab) and are listed in Table 1.

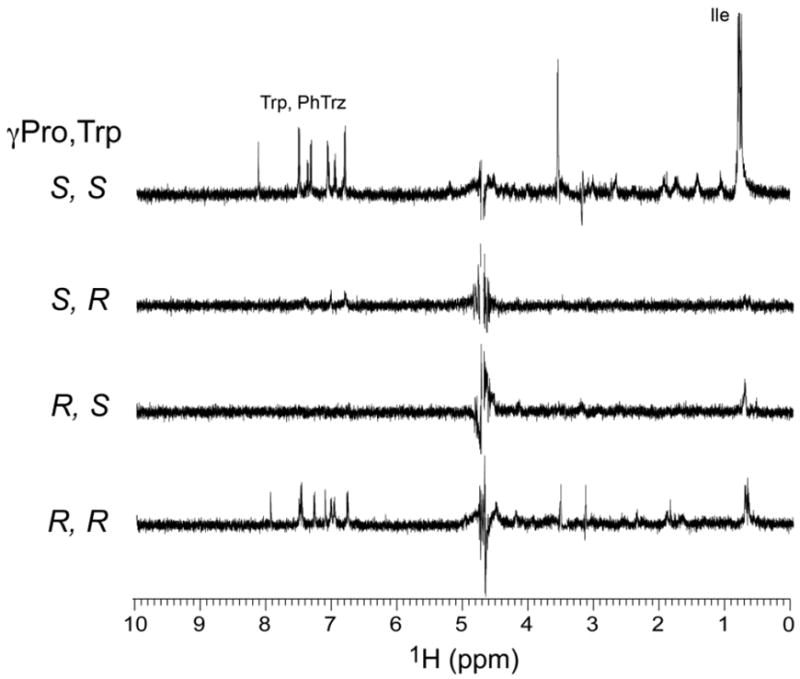

Previous work has shown that the stereochemistry of the chiral centers on peptide Pro-Cγ and Trp-Cα are very important for activity: when D-Trp is used along with a ferrocenyl appendage on the triazole, the peptide is almost inactive (30). Moreover, while the S configuration of the triazole on Pro-Cγ is active, the R configuration has similar activity to the parent peptide with no triazole (12p1 – see Table 1) (17). Here we aimed at further elucidating these findings through a systematic investigation of the stereochemistry around the two chiral centers and correlating that with NMR data and structural models. To simultaneously investigate the role of stereochemistry in both stereocenters of the hydrophobic X-W core in peptide activity, UM25 inhibitory potency was compared to other diastereomers where the Pro-Cγ and Trp-Cα atoms possessed R or S configurations. The original configuration with S-Pro-Cγ and S-Trp-Cα (UM25) is active but any change in configuration of either chiral center results in an inactive peptide (Figure 2 and Table 1), consistent with prior work on similar but longer peptides containing a ferrocenyl triazole (17, 30). Considering these results, we focused our modeling work only on UM101 and UM25, both of which have the S configuration in the chiral centers denoted above.

Simulation of a peptide-triazole/gp120-core encounter complex

Target gp120 conformation for docking studies

Previous work has shown that the parent peptide 12p1 does not inhibit binding of sCD4 to a mutant gp120 (S375W) (15) that has a propensity to sample the activated/CD4-bound state (48), while it inhibits binding of the F105 antibody to a mutant gp120 (I423P) which is inefficient at assuming the activated state (15, 48). Additionally, based on surface plasmon resonance (SPR) results, it was suggest that 12p1 inhibits sCD4 binding to gp120 through an allosteric mechanism (15). The above observations were used to propose that 12p1 traps gp120 in an inactive conformation that does not favor the CD4-bound state and lacks the bridging sheet. This is consistent with follow-up calorimetric studies which showed that binding of both 12p1 and peptide triazoles result in significantly less structuring of gp120 compared to binding of sCD4 (17, 30). Since a major determinant of gp120 structuring upon CD4 binding and activation is formation of the bridging sheet (49) and consistent with the aforementioned studies, we hypothesized that the gp120 conformation targeted by peptide triazoles is a conformation that has an unstructured bridging sheet.

There are three gp120 structures resolved to-date that lack the bridging sheet. These are gp120 complexes with mAbs F105, b12 and b13 (26, 27) (Figure 1b, c and d, respectively). We used the freely-available program Fpocket (http://fpocket.sourceforge.net) to detect druggable pockets on these structures (50, 51), where “druggable” is any pocket with a drug score above 0.5 (51). The algorithm failed to find any druggable pockets on the b12- and b13-bound conformations and indeed it failed to find any pocket at all on the b12-bound conformation. This is consistent with the fact that these structures were resolved with a highly engineered gp120 sequence containing multiple pocket-filling mutations and disulfide stitches which were introduced to stabilize the complexes for crystallization (26). In contrast, the Fpocket algorithm detected a large druggable pocket in the F105-bound structure overlapping the domain where the F43 pocket is located in the CD4-bound state (Figure S1). Additionally, the F105-bound conformation is the only bridging-sheet naïve conformation of gp120 which has been crystallographically resolved with a WT sequence (26). Finally, the F105-bound conformation is unique in lacking a secondary structure on both loops which make up the bridging-sheet, consistent with recent findings on the solution structure of these loops (52). Taking these points together, we selected this conformation as the target structure for further studies.

Role of the peptide hydrophobic core in binding

The I-X-W hydrophobic sequence in the middle of the peptide triazoles is crucial for their activity (30) and requires a specific X-W stereochemistry (17, 30). A survey of 103 high-resolution peptide/protein complexes in a prior study has shown that only a few amino acids of a peptide sequence typically contribute most of the interaction energy with its partner, commensurate with the “hot spot” hypothesis for general protein/protein interactions (53, 54). More interestingly, it was found that phenylalanine, leucine, tryptophan, tyrosine and isoleucine are by far the most frequently observed amino acids in peptide/protein interface hot spots (54). Based on these observations, and considering the previous work on truncated peptides (30), we hypothesized that the I-X-W hydrophobic core acts as the main interacting motif of the peptide.

Initial pose generation for simulations

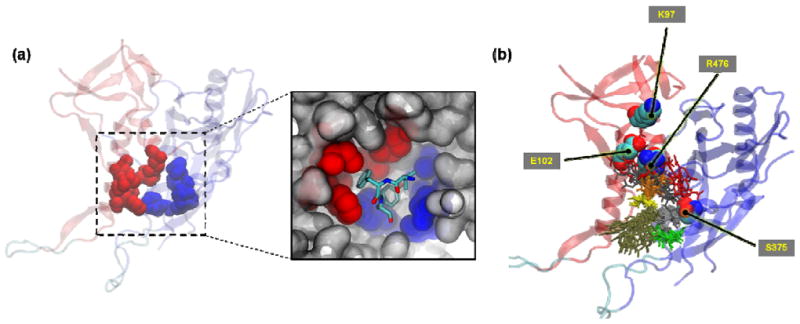

We combined the above two points (use of the F105-bound conformation and the possible role of the peptide hydrophobic core in gp120 binding) to formulate a strategy for generating initial peptide/gp120 poses. Examination of the F105/gp120 interface in the crystal structure revealed that the tip of the complementarity determining region of the third variable loop in the heavy chain (CDR-H3), comprised mainly of the three residues V100a, F100b, Y100c, inserted deeply into the (yet unformed) F43 pocket (Figure 3). Previously, it was reported that a pocket-filling S375W mutation in gp120 completely abrogated binding of the parent 12p1 peptide (15). Considering these observations, we further hypothesized that the peptide tryptophan could bind inside the F43 pocket, similar to Y100c of F105 and that the peptide isoleucine could insert into the small cavity formed between I108, I109, W112, F210, V255 and M475 of gp120, similar to F100b of F105 (Figure 3a). Interestingly, in the activated state of gp120, this latter pocket (hereafter referred to as “W427” pocket) is occupied by W427 on β20/β21, which is part of the bridging sheet. This conserved residue is necessary for CD4/gp120 interaction (24) and its mutation to valine can improve F105 recognition (55), leading one to speculate that in an unactivated conformation, this W427 pocket is unoccupied. Taken together, we postulated that the components of the peptide triazole hydrophobic core that are common between PTs and the parent 12p1 bind into these gp120 pockets (F43 and W427 pockets), partially mimicking the F105 CDR H3 binding in the F105-bound conformation of gp120. Thus, we used the Ile and Trp of the peptide to orient all MD-sampled peptide conformations over gp120 for initial pose generation. It is worth noting that such peptide orientation points the hydrophilic N-terminal sequence of the peptide toward the residues the mutation of which was shown to affect binding of the parent peptide 12p1 (K97, R476 and E102). These points are depicted in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

(a) F105-bound gp120 with the Fab removed. Red spheres show the residues that make up the small pocket at the interface of the inner and outer domains and blue spheres show some of the outer domain residues that are part of the (unformed) F43 cavity. The inset shows the placement of the tip of F105 CDR H3 loop residues V100a, F100b, Y100c (in cyan stick representation) at the gp120 interface. F100b inserts into the small pocket at the interface of the inner and outer domains (red spheres) and Y100c buries deep into the (unformed) F43 pocket (blue spheres) (b) Initial conformations of UM25/gp120 encounter complex before the start of minimization and equilibration steps. Peptide residues are colored based on residue number with red depicting the N-terminal (citrulline) and light green depicting the C-terminal (serine) residues. Gp120 backbone color-coding is that of Figure 1. Gp120 residues the mutation of which was found to affect binding of the parent peptide 12p1 (15) are shown in spheres and labeled along with S375.

Simulation results

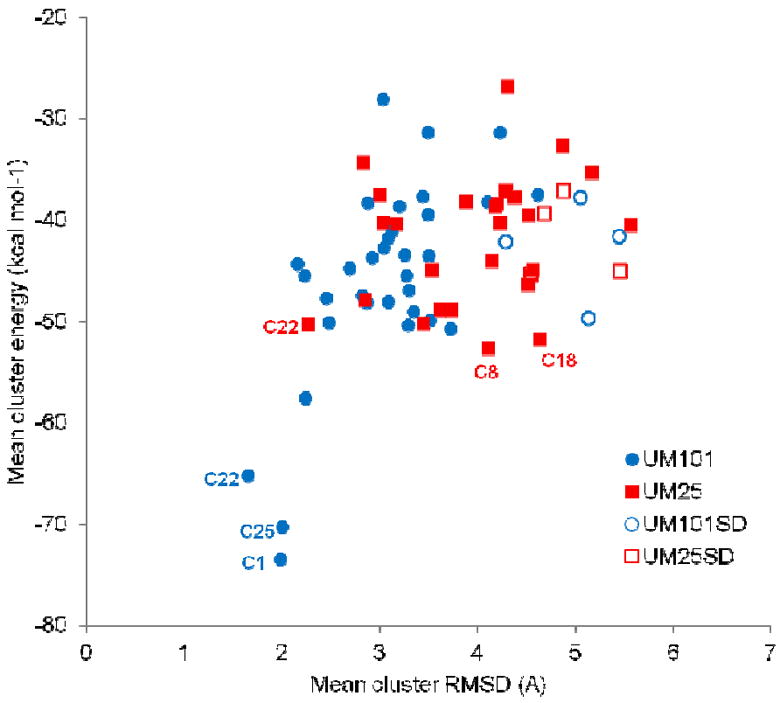

We tested the above hypotheses by applying the MD-based sampling scheme outlined in the Materials and Methods section to a set of initial poses for UM101 and UM25 peptides. Figure 3b shows the initial poses of the MD runs of UM25/gp120 complex. As an unbiased control, we also used the SwissDock server to produce energy-minimized peptide/gp120 docked complexes which we then subjected to the same all-atom explicit solvent MD scheme explained above (codenamed UM101SD and UM25SD, further discussed below). After removing the solvent and neutralizing ions, a PCA-based k-means clustering algorithm was used to group similar conformations together. The average peptide/gp120 interaction energy of each cluster was used as the main scoring criterion. Average RMSD (root mean squared deviation) of peptide heavy atoms within each cluster was used as a measure of cluster uniformity and pose stability, postulating that a low-energy favorable encounter complex should result in a structurally stable peptide and a cluster of similar conformations. Note that RMSD can be calculated against any reference conformation and the choice of the reference conformation will not have any significant effect on the relative difference between clusters. Figure 4 shows the mean interaction energy of each cluster plotted against the mean cluster RMSD. For UM101, there is a distinct collection of clusters which clearly are separated from the other clusters, showing a significant difference in potential energy and also lower intracluster fluctuations (as measured by intracluster RMSD). The three best scoring clusters were on average more than 10 kcal.mol-1 lower in energy scale than the next cluster. For UM25, there was no such obvious separation of clusters using similar metrics, although among the top three best scoring clusters (8, 18, 22), cluster 22 has the lowest mean RMSD, almost half the lowest energy cluster (cluster 8). As cluster 22 demonstrated the lowest energy and most stability (lower left of the plot in Figure 4) we chose cluster 22 as the top ranking cluster for UM25.

Figure 4.

Average scoring energy (CHARMM intermolecular interaction energy) of each cluster plotted versus average cluster variation (average RMSD over all cluster members) for all the runs after clustering of MD-generated conformations. UM101SD and UM25SD were runs initiated from best results out of SwissDock. Top three clusters from UM101 and UM25 are labeled in blue and red, respectively.

To compare these results with those of another docking method and to probe the effect of initiating our MD runs from a limited set of initial poses, we submitted UM101 and UM25 to the SwissDock server (45). We chose SwissDock over other freely available docking software primarily because it supports inclusion of non-natural amino acids out of the box and without the need for user-supplied force-filed parameters, provides an all-atom model of the complex and is suitable for relatively large ligands with many (>10) rotatable bonds. The results of MD runs and clustering for UM101 and UM25, starting from these optimized SwissDock poses, are represented in Figure 4 as UM101SD and UM25SD. The initial poses, based on a priori knowledge of gp120 conformation and past experimental knowledge of 12p1/gp120 interactions, result in clusters which are more homogenous and have lower interaction energies (compare open and closed symbols in Figure 4). Interestingly, after MD equilibration, the UM101SD pose with the lowest global interaction energy resulted in a conformation in which the peptide hydrophobic core was roughly positioned similarly to our initial UM101/UM25 docking poses, although UM101SD was initiated from a different conformation generated by the SwissDock server (Figure S2).

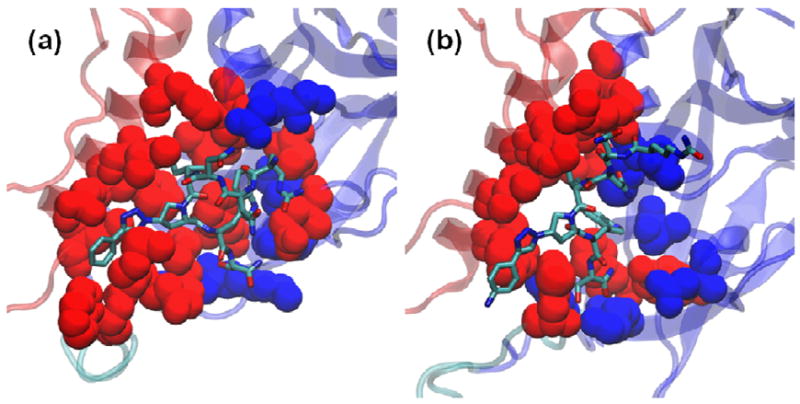

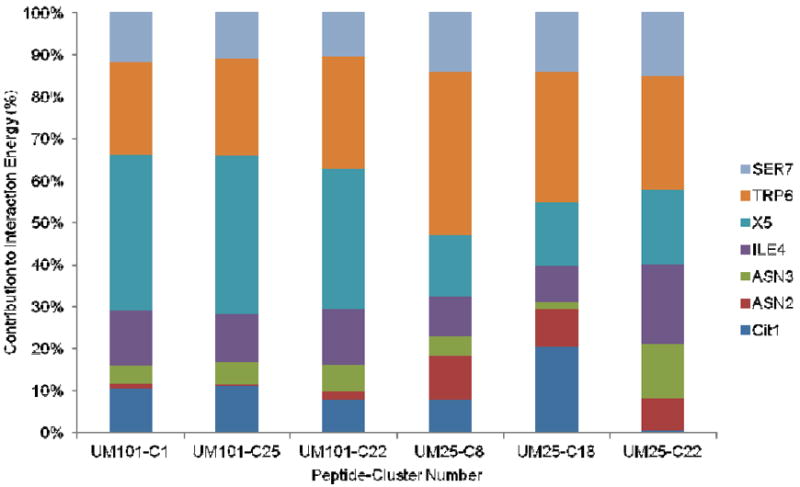

We further examined specific gp120/peptide triazole contacts for the top ranking UM101/UM25 clusters (Figure 5). We measured the intermolecular interaction energy for all members of a cluster and determined the fraction of that energy contributed by each gp120 residue (Table S1). We also counted the intermolecular hydrogen bonds (with a distance cut-off of 3 Ȧ and angular cut off of 30°) and determined the fraction of conformations in each cluster where a gp120 residue participates in hydrogen bonds. This fraction was used as the intermolecular hydrogen bond occupancy for that residue (Table S2). These data are summarized in Figure 5 (and further detailed in Figures S3-S4). Here, we have colored gp120 residues which contribute more than 2% of the intermolecular interaction energy for each cluster in red. Gp120 residues participating in intermolecular hydrogen bonds are shown in blue and for residues belonging to both groups, if the hydrogen bond occupancy was less than 10%, we colored the residues in red.

Figure 5.

Minimum energy representatives from the top scoring clusters for (a) UM101 (cluster 1) and (b) UM25 (cluster 22). Heavy atoms of gp120 residues which contribute more than 2% of the total interaction energy for each cluster are shown as red spheres. Heavy atoms of residues which act as a donor or acceptor of hydrogen bonds with occupancy values > 1% are shown as blue spheres. For residues which appear in both groups, those with hydrogen bond occupancy < 10% are colored red. Peptide heavy atoms are depicted in sticks. Backbones of the gp120 inner and outer domains are color coded as in Figure 1.

The major structural difference between the top ranking clusters of UM101 and UM25 is the burial of the triazole moiety at the interface of α1 C-terminus and β20/β21 in the former. This contributes on average 26-27 kcalmol-1 to the potential energy of interaction between the peptide and gp120. Measuring the fraction of potential energy contributed by each peptide residue, and averaging the results for the top three clusters, shows that the X-W cluster contributed 60 and 50 percent of the interaction energy in UM101 and UM25, respectively (Figure 6). This is consistent with previous results which showed these two residues to be critical for any functionality in the peptide (30). Although both peptides are similar in the overall contribution of this hydrophobic core to the interaction energy, the relative role of the two residues is drastically different. While in UM101 the triazole makes up for 36 percent of the energy versus 24 percent for the tryptophan, in UM25 it is the tryptophan which contributes more (32%) than the triazole (16%). Considering the depicted models of the complex (Figure 5), such results reflect the observation that in UM101 a large hydrophobic moiety is desolvated while in UM25 it stays solvated though still in contact with the protein. Interestingly, UM25 has a similar IC50 for inhibition of gp120/sCD4 interaction as that of 12p1, which does not contain a triazole appendage (Table 1). The role of hydrophobic group desolvation in improving the affinity of ligands is well-documented (56, 57) and is consistent with previous results which show a direct correlation between the hydrophobic solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of different triazole derivatives and the affinity of peptide triazoles (17). We also observed that UM101 is about five times more potent than UM25 in inhibiting gp120 binding to sCD4 (Table 1). Burial of the more hydrophobic triazole at the interface of the inner and outer domains provides an explanation for the significantly improved potency of UM101 over UM25.

Figure 6.

Contribution of each peptide residue to peptide/protein interaction energy in the three top ranking clusters of UM101 and UM25 from the simulations. C1, C25, etc. denote cluster numbers.

Correlation of the model of peptide/gp120 complex with experimental data and prediction of important contacts

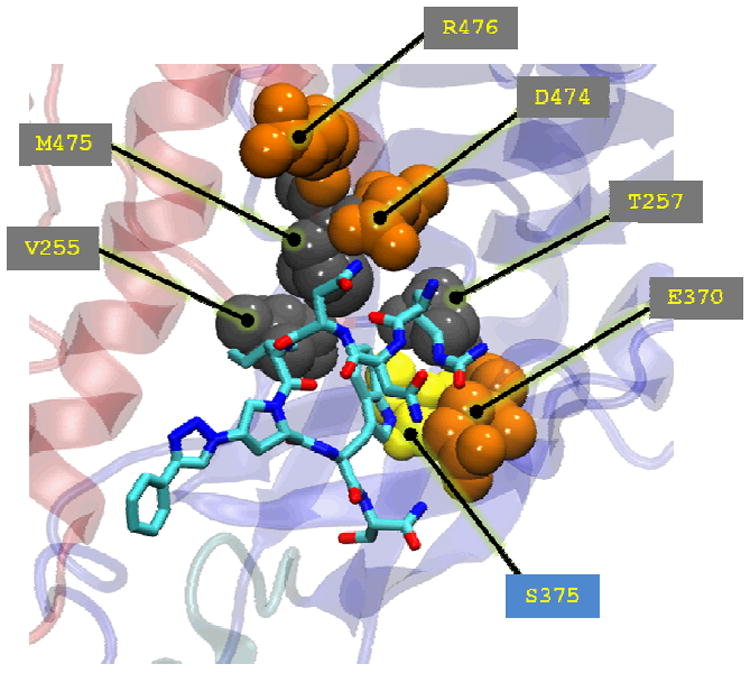

We used the past work on the interaction of the parent 12p1 with gp120 to guide the initial pose generation for a peptide triazole/gp120 encounter complex (28, 58). More specifically, we took into account the effect that the S375W and I423P mutations have on 12p1 inhibition of gp120 interactions with different ligands, along with information on the conformation targeted by the peptide gleaned from antibody binding data and isothermal titration calorimetry. More recent work in our group, through analysis of peptide triazole binding to a panel of gp120 alanine mutants, demonstrated that D474 and T257 had a significant effect on PT/gp120 interactions, with smaller effects from E370, M475, V255 and R476 (32). All of these residues are among those which contribute to van der Waals and electrostatic interactions with the peptide (Table S1) or hydrogen bonds (Table S2) in the simulations. Since those studies were done using a longer, high affinity peptide with a ferrocenyl triazole (KR21), we only consider our UM101 simulations for comparison. We have shown the top UM101 pose (cluster-1) along with the above residues in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Experimentally verified gp120 residues important for peptide binding (spheres) in the context of UM101 minimum-energy conformation of cluster-1 (Figure 5a). Hydrophilic residues surrounding the putative F43 pocket are colored orange, residues lining the inside of the pocket are colored gray and gp120 S375 (discussed later in the text) is colored yellow. Gp120 backbone coloring is that of Figure 1.

Focusing first on the hydrophilic residues surrounding the F43 pocket, E370 or D474 side chains serve as hydrogen bond acceptors from the charged N-terminus backbone of both UM101 and UM25 peptides (see Table S2). In contrast, we persistent interactions were observed with R476 only in the UM25 docked pose. In addition, such a positioning of the peptide N-terminus puts the two asparagines at interaction distances from a series of hydrophilic gp120 residues on the CD4-binding loop (E370, D368), the α5 helix (D474, D476) and the α1 helix (E102). Indeed the top two UM101 clusters are different only in how the N-terminus is placed relative to these gp120 domains (not shown). In cluster 1, the N-terminus and N3 of the peptide interact with D474 (hydrogen bond occupancy ~ 80% - Table S2) while the citrulline (Cit1) side chain and N2 interact with E370 and D368 (VdW and electrostatic – Table S1). In cluster 25 (the second ranking cluster), their placements are exchanged (D370-Cit1 hydrogen bond occupancy ~ 42%; N3-D474 occupancy ~5%. data not shown). In other words, the hydrophilic N-terminus of the peptide might be able to use the ring of hydrophilic residues surrounding the F43 pocket for hydrogen-bonding interactions with the side chains of the two peptide asparagines, or salt-bridge formation with the charged N-terminus of the peptide. This is also consistent with previous studies which have showed that hydrophilic mutations toward the N-terminus of the peptide yield compounds which still maintain activity (30). For example, mutation of the citrulline side chain to arginine to glutamic acid barely has any effect on peptide binding. Even complete deletions at these positions are tolerated without loss of function. Side-chain variability is much less tolerated at the N-terminus quickly vanishes as one gets closer to the hydrophobic core. Although peptides with hydrophilic mutations at the N-terminal asparagine maintained some activity, variations in the second asparagine led to inactive peptide (30). These observations are consistent with our model, wherein the peptide N-terminus can be localized on either side of the entrance to the (putative unformed) F43 pocket (D474 or E370) and allow formation of hydrogen bonding networks through interactions of the two asparagine side chains with the remaining hydrophilic residues on gp120.

The gp120 residues T257, M475 and V255 line the inside of the F43 cavity in the CD4-bound conformation and are completely buried in that state, while they are more exposed in the non-activated conformations such as the F105-bound conformation. In the latter, more “open” inactive conformations, these residues form the outer domain wall of the yet unformed F43 pocket. Combined together, these residues contribute about 12% of the total potential energy of interaction between UM101 and gp120 cluster-1. V255 and M475 contribute to the gp120 W427 pocket, which is plugged by the peptide isoleucine in the docked model. While these residues seem to interact with both peptide Ile and Trp, the critical T257 seems to solely interact with the important peptide tryptophan. Together, these data show that our model is consistent with recent experimental data on PT/gp120 interface.

The gp120 residues which were experimentally determined to affect peptide/gp120 interactions are all among the contacts which contribute either to VdW/electrostatic interaction (Table S1) or hydrogen bonds (Table S2) between the peptide and gp120 in the simulations. The only exception is R476 which only mildly affected the PT/gp120 interaction (32). This residue was found to be more important for the parent, lower affinity peptide 12p1 (15). Interestingly, in our simulations, this residue contributed to complex stability of only the lower affinity peptide UM25. In addition to these contacts, we observed other gp120 residues which may be important for interactions with PTs, but were not included in the studies of Tuzer et al. (32). The functionally critical peptide tryptophan donates a persistent hydrogen bond to gp120 S375 while its phenyl ring rests against the methyl group of T257 (The role of this latter contact will be discussed further below). The orientation of the peptide tryptophan shown in the UM101 cluster 1 stacks the indole ring against the highly conserved bulky F382 inside the pocket, commensurate with the importance of such π-π interactions in ligand recognition (56) and mimicking the F105 Y100c interaction with gp120 F382 (Figure 3a). W112, F382, I423, M426, I109, L116 and N425 all contribute significantly to the intermolecular interaction energy of the UM101/gp120 complex (Table S1). Overall, these observations suggest that the proposed model of the peptide triazole/gp120 interaction is consistent with the current data on the role of different gp120 residues in modulating peptide interactions.

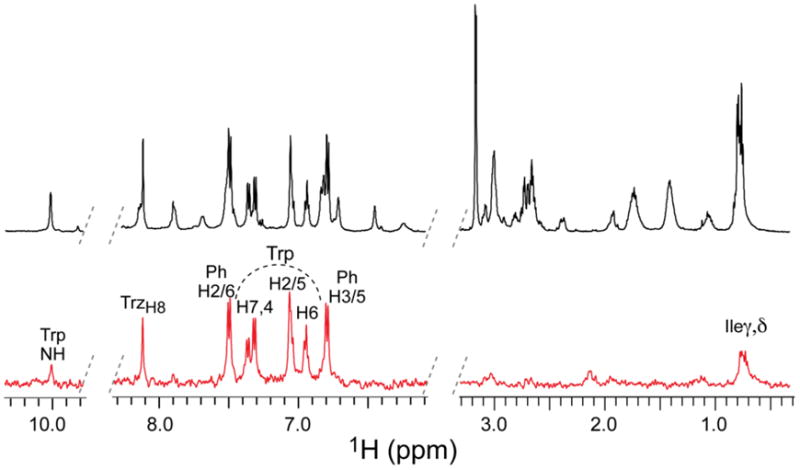

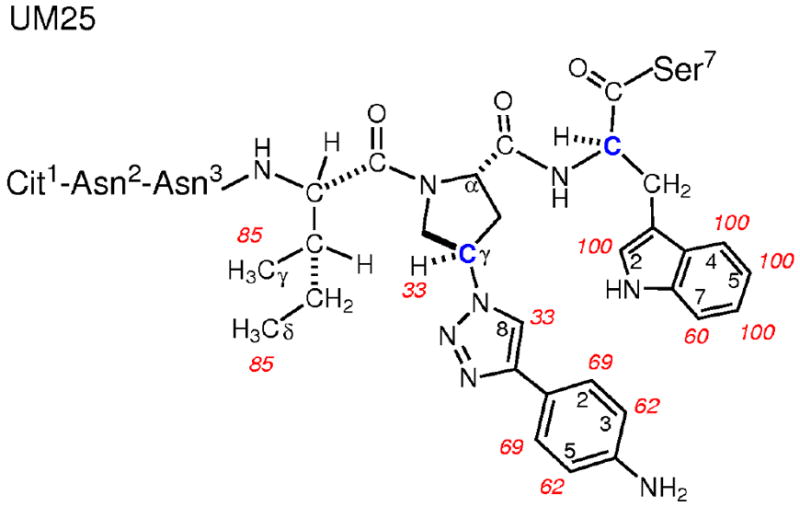

Characterization of peptide triazole binding to gp120 by NMR

We used Saturation Transfer Difference NMR (STD NMR) to independently characterize the binding of peptide triazoles to soluble gp120. In this method, saturation of protein resonances results in magnetization transfer from the receptor to the bound ligand in a distance-dependent manner. We introduced a para-aminophenyl group in place of the phenyl in UM101 in order to increase the off-rate of peptide/gp120 interaction for optimal results in STD NMR experiments (47) and to improve peptide solubility. In a difference spectrum, signals corresponding to protons in closest proximity to the protein in the bound state appear as the strongest signals. Together with full chemical shift assignments (Table S3) made via 1H-1H and 1H-13C 2D NMR experiments, an atomic level description of a binding epitope can be obtained.

As seen in Figure 8, strong STD enhancements (red spectrum) are seen for numerous protons of UM25. These include protons of the indole ring of Trp, and the p-aminophenyl triazole group, as well as γ and δ methyl groups of isoleucine. When compared to the reference spectrum, the strongest signals in the difference spectrum correspond to H-2/4/6/7 of tryptophan (Figure 9). The percent enhancement for each of the remaining signals was normalized to these protons, and the percent enhancements for each are shown in Figure 9 and Table 2. In addition to Trp, the side chains of Ile and Pro-Hγ strongly contribute to the binding to gp120, with STD enhancements ranging from 60 to 85%. Apart from protons located within these three residues, there are no other large enhancements observed in the difference spectra. Together these data suggest that these three residues in large part govern binding of UM25 to gp120. This is consistent with suggestions from the simulation model that the hydrophobic core of peptide triazoles is the major binding partner to gp120, with the I-X-W motif contributing about 60% of the interaction energy in UM25.

Figure 8.

STD NMR spectrum of UM25. Reference and difference spectra (see Materials and Methods) are shown in black and red, respectively (see Materials and Methods). Protons exhibiting the largest enhancements are labeled (see Table 2 for quantification). Protons of Trp are located under the curved, dotted line. Trz and Ph denote the triazole and p-aminophenyl rings, respectively (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Chemical structure of UM25 showing protons involved in gp120 binding. Percent enhancements observed in the STD NMR spectrum are labeled in red (Table 2). The two stereocenters studied for UM25 are indicated as blue carbons.

Table 2.

Percent enhancements for UM25 binding to gp120 observed by STD NMR.

| Residue | Proton | Enhancement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ile4 | Meγ | ~85a |

| Meδ | ~85a | |

|

| ||

| X5 | Hγ | 33 |

| H-2/6 | 69b | |

| H-3/5 | 62c | |

| H-8Trz | 33 | |

|

| ||

| Trp6 | H-2/5 | 100c |

| H-4 | 100 | |

| H-6 | 100 | |

| H-7 | 60 | |

Average of two methyl signals;

average of H-2/6;

average of H-3/5.

Binding of UM25 to gp120 is stereospecific

Previously we demonstrated that the S configurations on Trp-Cα and Pro-Cγ were important for the inhibitory function of peptide triazoles (17, 30). In this work, we changed the stereochemistry of these two chiral centers and observed that changing the Trp-Cα configuration from S to R renders the peptide almost inactive, while changing the Pro-Cγ at the triazole derivative attachment point from S to R reverts the activity back to the parent peptide without the triazole (Table 1 and Figure 2). To directly compare binding interactions between the four diastereomeric analogs of UM25 to gp120, we recorded STD NMR spectra on each of these peptides in complex with gp120. All samples were prepared and spectra recorded in an identical manner (Materials and Methods). For comparison, the four difference spectra are shown as stacked plots in Figure 10. The STD NMR spectra show that the UM25 analog bearing D-Trp (S configuration of the side chain) in the wild type background, as well as the analog bearing R-Pro-Hγ in the presence of L-Trp, do not bind to gp120. Interestingly, for the UM25 analog in which both stereocenters have been inverted, to R-Pro-Hγ and D-Trp, binding to gp120 is observed. However, the signal to noise for this spectrum is less than half that measured for wild type UM25, and while enhancements are seen for protons in the Pro-Hγ and Trp residues, negligible enhancements are observed for Ile. Thus, in addition to an apparent reduction in binding affinity, these data suggest that the entire tripartite arrangement presented by Ile, S-Pro-Hγ, and Trp are required for functional binding to gp120.

Figure 10.

STD NMR spectra of the four diastereomers of UM25 in complex with gp120. Stereochemistry of the two chiral centers is indicated on the left of each spectrum. PhTrz denotes the p-aminophenyl triazole.

Experimental test of model predictions

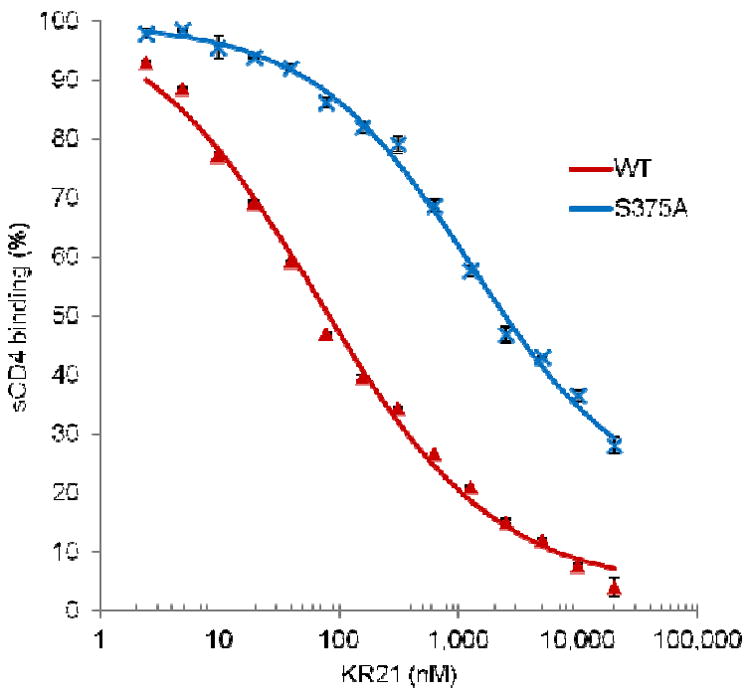

While the MD simulation model is consistent with recent mutational studies on PT/gp120 interaction (32) and the STD NMR studies presented above, a more direct verification of the model validity would be testing the predictions it provides. Considering the critical role the peptide tryptophan plays in its activity (16, 17), we examined its contacts with gp120 in the model more closely. Interestingly, a persistent hydrogen bond between the Trp side-chain and gp120 S375 is observed in the UM101 model (as well as the UM25 model) (Figure 5 and Table 2). S375 is among the residues which line the inside of the F43 cavity (Figure 1, Figure 7) and, as such, can be considered a hydrogen bonding partner in a mostly hydrophobic cavity. Hydrogen bonds in hydrophobic pockets have been shown to be major contributors to stabilization of protein-ligand interactions (51, 59, 60). These observations led us to postulate that the hydrogen bond between the peptide Trp side chain and gp120 S375 is important for peptide activity and that breaking this bond should lead to decreased activity of peptide triazoles. To test this hypothesis, we probed the interaction of a biotinylated peptide triazole (KR21, Table 1) with gp120 S375A mutant.

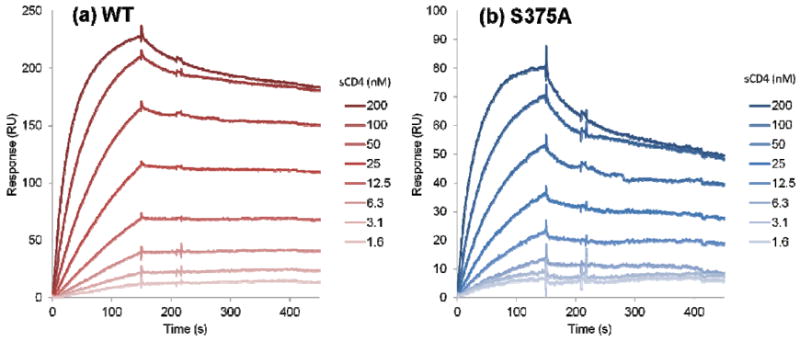

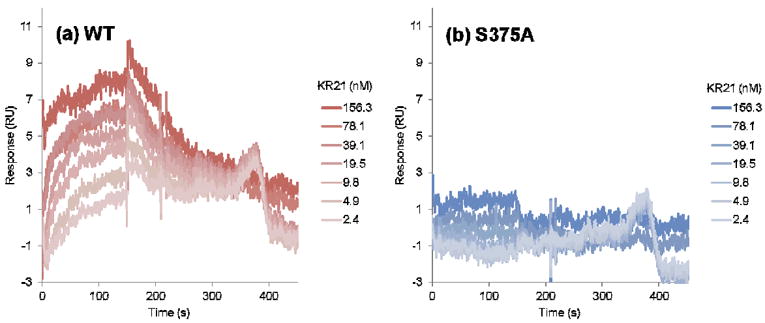

We first verified the functionality of the S375A gp120 mutant by measuring its affinity for sCD4 (Figure 11). Fitting of the sensorgram data to a steady state 1:1 affinity model (Materials and Methods) yielded KD = 37 nM for WT and KD = 41 nM for S375A gp120. Hence, S375A maintains correct gp120 folding and activity. We then probed the affinity of KR21 for this mutant by a direct binding SPR assay wherein serial dilutions of the peptide were injected over immobilized WT and S375A (Figure 12). Steady state fits for WT sensograms yielded KD = 9 nM for KR21/gp120 interactions, but KR21 binding to S375A was severely disrupted and we could not fit the data. A reduction in KR21 affinity for S375A, combined with the unaltered affinity of the mutant for sCD4, leads one to speculate that the latter would be more resistant to KR21 inhibition of gp120/sCD4 interaction. Measuring the inhibitory potency of KR21 for PT/gp120 interaction provides an alternative means to quantify the effect of S375A mutation on PT/gp120 interaction. We mixed a non-saturating amount of sCD4 (50 nM) with serial dilutions of KR21 and injected the mixture over immobilized gp120. The resulting SPR sensograms are shown in Figure S5. Steady state response values at 290 seconds (end of the association phase), normalized to the response in absence of the peptide, were used to generate the dose-response data in Figure 13. Fitting of the results to a 4-parameter logistic curve yielded IC50 values of 65 nM and 1283 nM for WT and S375A, respectively. Consistent with the direct binding data, the competition results show a large-scale reduction (20 fold) in the sCD4/S375A inhibitory potency of KR21 compared to WT gp120. This is consistent with the simulation-based hypothesis that the peptide tryptophan side chain makes a hydrogen bond with the gp120 S375 inside the F43 pocket, and that disruption of this bond will significantly affect PT/gp120 interaction.

Figure 11.

Binding of sCD4 to immobilized (a) WT and (b) S375A gp120. Lighter color in the SPR signal denotes lower sCD4 concentration. Fitting of the data to a steady state affinity model yielded KD = 37 nM for WT and KD = 41 nM for S375A gp120. Data are averages of duplicates.

Figure 12.

Direct binding of KR21 peptide triazole to immobilized (a) WT and (b) S375A gp120. Darker color in the SPR signal denotes higher peptide concentration. Fitting of the data for WT to a steady state affinity model yielded KD = 9 nM. S375A sensograms did not approach saturation and hence could not be fitted. Data are averages of triplicates.

Figure 13.

KR21 inhibition of WT (red) and S375A (blue) gp120 interaction with sCD4. Data points were extracted from sensograms of Figure S5 and fit to a 4-parameter sigmoidal equation resulting in IC50 values of 65 nM for WT and 1283 nM for S375A.

Discussion

The ability of peptide triazoles to inactivate HIV-1 by specifically targeting a highly conserved site on Env gp120 (32), combined with the inability to date to obtain a crystallographi structure of the complex, provided the impetus in the current study to simulate the complex using molecular dynamics simulation. Prior work has suggested that peptide trizoles stabilize gp120 in a conformation that is not as structured as the activated form of the protein and lacks an ordered bridging sheet (21, 22). Here, we used the bridging-sheet disordered F105-bound gp120 conformation as the simulation target and employed an explicit-solvent MD-based scheme to sample structures of peptide-protein encounter complex. Clusters of conformation with minimum average energy and intracluster RMSD were selected for further analysis. Measuring the peptide/gp120 interaction energy in these clusters showed that the I-X-W hydrophobic cluster is the hot-spot for peptide/gp120 interactions, contributing 50-60% of the intermolecular nonbonded energy. These were consistent with previous reports on the importance of the N-N-I-X-W motif for peptide activity (15, 30). In addition, STD NMR analysis confirmed the importance of the I-X-W motif in the peptide for gp120 binding and showed that binding of this tripartite hydrophobic domain is the sole contributor to STD NMR signals of the peptide. In simulations, a specific geometry in the peptide hydrophobic core was required to insert into the hydrophobic cavities present in the F105-bound gp120: the minimum energy poses from simulations showed that a change of stereochemistry at Trp-Cα and Pro-Cγ chiral centers led to clashes with the protein surface or force the triazole moiety away from the protein surface. Consistent with the simulation results, our NMR experiments also showed no signal for binding of peptide diastereomers with R-Trp-Cα and R-Pro-Cγ. We measured the contribution to the interaction energies from different gp120 residues and found that those that were experimentally determined to be important for peptide triazole binding were also either major contributors to the interaction energy or participated in persistent hydrogen bonds with the peptide. Furthermore, we identified additional gp120 residues the mutation of which would be predicted to reduce gp120 affinity. Among those, we tested the effect of mutating gp120 S375 on binding of a peptide triazole variant (KR21). Consistent with our prediction, this mutation decreased the sCD4 IC50 of KR21 by 20-fold. Together these results provide a self-consistent model, of the peptide triazole/gp120 encounter complex, which can be used to both design a stabilized covalent conjugate for further structural studies and to test ideas for rational design of improved entry inhibitors.

We used the F105-bound gp120 conformation as our target for PT/gp120 complex simulations, based on previous studies suggesting that peptide triazoles bind to a bridging sheet naïve gp120 conformation (23, 25, 28, 29). We used the Fpocket algorithm (25) to look for suitable pockets on available bridging sheet naïve gp120 crystal structures. Previous studies have shown that peptides mostly bind to the largest pockets on protein surfaces (54) and the F105-bound structure was the only conformation which displayed a large druggable cavity. In addition, in contrast to the b12- and b13-bound gp120 conformations which were resolved with highly engineered sequences, the F105/gp120 crystal structure was resolved with a WT sequence and did not contain any engineered mutations (28, 30). Interestingly, recent hydrogen/deuterium exchange studies on the full-length gp120 conformations in solution showed that the β2/β3 and β20/β21 domains which fold into the bridging sheet in the activated state, are largely disordered in the unliganded gp120 (52). This is a unique property of the gp120 conformation in complex with F105, in contrast to the b12-b and b13-bound structures. Finally, recent simulation studies have demonstrated the flexibility of β20/β20 in the F105-bound conformation (25) and the corresponding amenability of the F43 pocket to expansion (61). Despite the above points, we used the SwissDock server to generate possible initial PT/gp120 docked poses but all of the top 20 poses were on the gp120 silent face and none were close to the functionally relevant gp120 F43 pocket. Taking together, these results all support our choice of the F105-bound state as the target for docking studies.

We clustered the PT/gp120 complexes from MD simulations based on peptide conformations and selected the most homogenous clusters with the lowest values of the intermolecular part of CHARMM interactioin energy as the best scoring clusters (Figure 4). Simulation of the encounter complex of both UM101 and UM25 showed a similar binding pose for the peptide hydrophobic core and slightly different trajectories for the peptide N-termini (Figure 5). The common hydrophobic core contacts were reflected in gp120 residues contributing significantly to the interaction energy (Table S1) or intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Table S2). Our simulations point to the I-X-W motif as the most important contributor of interaction energy between gp120 and PT (Figure 6). Similarly, our STD-NMR results point to the hydrophobic I-X-W motif as the only peptide/gp120 interface (Figure 9). Both observations are consistent with previous studies that established N-N-I-X-W as the minimum sequence required for peptide activity (26).

We used peptide triazoles with phenyl (UM101) and para-aminophenyl triazoles (UM25) on the central proline for our simulation and STD-NMR studies. The latter facilitated our STD-NMR studies by providing better solubility and faster off-rates while the high affinity of the former for gp120 provided us with a peptide which better represented the high-potency members of this class of molecules. We also synthesized stereoisomers of UM25 with different configurations around the tryptophan Cα and azidoproline Cγ (Figure 9). Consistent with our ELISA results on their lack of inhibitory potency (Figure 2), we did not observe any significant STD-NMR signal for any of the stereoisomers (Figure 10). Our simulations suggest that a precise geometry around the tripartite hydrophobic core of PTs is necessary for their function, consistent with previous studies on longer PT sequences (23). Hence this model provides a working hypothesis for these effects by proposing that a change of stereochemistry at the above chiral centers will lead to clashes with the protein surface (for tryptophan side-chain) or force the triazole moiety away from the protein and into the solvent (for triazole).

While the hydrophobic core conformation in the encounter complex for both UM101 and UM25 is similar, more variability is observed on the N-terminus. Past work in our group has shown that the N-terminal hydrophilic extension on the peptides can be modified to include positively or negatively charged or neutral residues without much difference in peptide/gp120 affinity (30). Such findings are consistent with our findings from simulations. It has been suggested that electrostatic interactions serve to guide peptide-protein interactions to an initial, metastable encounter complex which is then stabilized through binding of a small number of hotspot residues (54, 62). Therefore we think that hydrogen-bonding, hydrophilic N-terminal extension residues of the peptide bind to the ring of charged residues surrounding the F43 pocket (like E370 and D474, Figure 7 and Tables S1 and S2) and localize it close to this flexible pocket and then in a second step, the hydrophobic hotspot residues bind to the (possibly transiently exposed) F43 pocket, latching the peptide onto gp120. Launching a 200 ns MD simulation from the minimum energy cluster 1 of UM101, we observed that the hydrophobic core of the peptide is solidly bound to gp120 (peptide core heavy atom RMSD ≅ 2 Ȧ) while the hydrophilic N-terminus is flexible (data not shown) and transiently samples the two hydrophilic domains surrounding the F43 cavity (centered on D474 and E370, both of which were found to be important PT/gp120 contacts) (32).

The most significant difference in the peptide pose of the top scoring complexes for UM101 and UM25 was at the triazole appendage. While this moiety was fully buried (FSASA=0.13) in the simulated structure of UM101/gp120 (Figure 5a) and contributed the largest fraction of intermolecular interaction energy, it stayed relatively soluble (FSASA=0.62) in the case of UM25 and its contribution to the interaction energy was reduced, surpassed by that of the peptide tryptophan (Figure 6). Previous studies established that hydrophobic substitutions on the triazole enhance the peptide potency (17), consistent with the generally accepted positive contribution of hydrophobic group desolvation to increasing drug potency (56, 57). These results are further corroborated with our STD NMR results which show difference signals for the the triazole moiety (Figure 9), although the size of the signal is smaller than the tryptophan signals. Though we did not observe complete, persistent burial of the triazole in UM25 (which was used in NMR studies here) simulations, the triazole in this peptide stayed close to gp120 surface. Such proximity can give rise to saturation transfer difference signals (63). Interestingly, UM25 inhibitory potency of gp120/sCD4 interaction is similar to that of 12p1, which lacks the triazole moiety and hence will lack the positive contribution its burial provides for intermolecular interaction energy. Complete burial of the phenyl triazole of the high-affinity UM101 peptide at the interface of β20/β21 and the α1 C-terminus and lack of such persistent desolvation for the lower-affinity UM25 para-aminophenyl triazole provides a structural explanation for the improved potency of the former peptide.

The strongest STD-NMR signals arise from the hydrogens on the tryptophan indole, indicating that this residue is in intimate contact with gp120. This is consistent with the simulations results which show that the peptide tryptophan is stabilized inside the (yet unformed) gp120 F43 cavity, particularly through a side chain hydrogen bond with gp120 S375. These two independent observations are consistent with past results which showed that mutation of this tryptophan abrogates peptide activity (15, 16).

The next set of strong signals arises from Ile4 of the peptide which in our model resides inside a shallow cavity at the interface of the inner and outer domains, we called “W427” pocket (Figure 3 and Figure 5). As such, the peptide tryptophan fills a cavity which is occupied by F105 F100b. Based on our model, we think introduction of more hydrophobic residues (like Phe) at this position on the peptide can improve its inhibitory potency.

The triazole appendage makes up the last bit of the I-X-W “tripartite” pharmacophore, with STD enhancements as high as 80% of those observed for the tryptophan protons. We find it surprising that moving from the triazole ring toward the para-aminophenyl appendage, the STD NMR signal seems to decrease. This may indicate burial of this moiety inside a transient or flexible pocket. The interface between two flexible domains may be a plausible option for such a pocket.

Our data on gp120 contacts at the PT/gp120 interface correlate with recent studies wherein gp120 residues important for PT binding were investigated through alanine scanning mutagenesis of some gp120 mutants (32). Residues which were shown to be important for PT binding to gp120 (D474, T257, E370, M475, V255 and R476) (32) were also found in our simulations to contribute to either the intermolecular interaction energy or hydrogen-bond formation in the PT/gp120 complex for both UM101 and UM25 simulations, although R476 was only implicated in simulations of the low affinity UM25 peptide. This latter residue was found to impact interactions of the parent low affinity 12p1 peptide with gp120 (15), but had a smaller impact on the interactions of the higher affinity variants (like KR21) compared to D474 or T257. Since the mutational studies were performed with a high affinity peptide (KR21), we focused on the UM101/gp120 pose generated from the simulations.

In addition to being consistent with these observations, our model suggests additional contacts which were not studied by Tuzer et al. (32): W112, F382, I423, M426, I109, L116 and N425 were gp120 residues which had the largest contribution to interaction energy with UM101. It would be interesting to test the effect of mutations at these sites on PT/gp120 interactions. Therefore, our model is not only consistent with recent experimental data on the PT/gp120 interaction, but also can be used to make specific predictions on how one might further test the model validity using additional mutations.

As an example, and to further test the predictive utility of our model, we focused on gp120 S375. The side chain of this residue in our model accepts a persistent hydrogen bond from the critical peptide tryptophan side chain (Figure 7 and Table S2). We hypothesized that this buried hydrogen bond contributes significantly to stability of the PT/gp120 complex. To test this we probed the interactions of a PT variant with a C-terminal biotin (KR21) with the gp120 mutant S375A using SPR. Direct binding experiments (Figure 12) showed that KR21 affinity to gp120 is significantly reduced. To quantify the extent of this effect, we tested the KR21 inhibitory potency against S375A interaction with sCD4. Although S375A affinity for sCD4 is almost unchanged compared to WT, KR21 inhibitory potency for this mutant is 20-fold reduced (Figure 13). This was consistent with our model-based prediction and provides a direct evidence for utility of this model in structure based studies of PT/gp120 interactions.

Among all the clades tested (clades A-D), only a gp120 sequence (90CM243) from the circulating recombinant form AE (CRF01_AE) was fully resistant to peptide triazole inhibition of sCD4 binding (up to 4 μM peptide triazoles) (20). 99% of sequences in this strain of HIV-1 have a histidine at position 375 (64). Interestingly, the S375W gp120 mutant was found to be resistant to the parent 12p1 peptide (15) while we observed that S375A has reduced sensitivity to PTs (Figure 13). We think the lower potency of KR21 for S375A argues for the role of a direct contact effect in this case and possibly a combination of direct contact and conformational alteration for S375W. The significantly larger side chain of S375W would completely obstruct the critical peptide tryptophan from accessing contacts inside the F43 pocket. Considering the similarity of the aromatic tryptophan and histidine side chains (64), we think complete blockade of all peptide tryptophan contacts inside the F43 pocket (Figure 7) might explain resistance of 90CM243 strain to peptide triazoles. Therefore we think our model can provide a structure-based hypothesis for the observed resistance of a gp120 strain. Furthermore, we predict that all clade AE sequences will be resistant to peptide triazoles, as long as they have a bulky hydrophobic side chain like a histidine at position 375.

Further studies will try to overcome the limitations of our current model. We do not know the conformation of gp120 that is targeted by the peptide. Using the “right” target conformation immensely impacts the success of docking models (65). In using MD to drive conformational sampling of both the peptide and the protein, our aim was to start from a potentially “wrong” conformation and arrive at a local minimum on some complex free energy surface that would provide a better picture of the peptide/gp120 interactions. Previous work in our lab has generated ensembles of bridging sheet naïve gp120 conformations (66) which can be used using ensemble docking methods (65). Our use of similarity-derived CHARMM parameters for the triazole moiety might have negatively impacted the quality of the results. Although surveys of PDB structures have found that ligand strain energies of several kT are common (67), supporting some acceptable margin of error in dihedral parameters used in this work, we recognize that improving the quality of these parameters would be important for improving the current model. Finally, we used a simple nonbonded interaction energy score for ranking the MD-generated poses. Although other, more advanced scoring schemes can be used, the ambiguity in the target conformation of gp120 argues against investing in such expensive methods since, using such a simple scoring scheme, we were able to distinguish poses which are consistent with independently derived experimental results. In addition to the single mutation studied here (S375A), testing additional predictions of the current model experimentally (i.e. introduction of phenylalanine in place of Ile4 on peptide to improve its affinity or mutating W112 or I109 on gp120 to probe the effect on peptide binding) can provide more direct cues to refining the model using more rigorous simulation methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors acknowledge the National Institutes of Health for support through grants NIH 5R21AI093248-02 and 5R21AI091513-02 (A.E., C.F.A. and I.M.C.), NIH 5P01GM056550 (A.E., F.T., U.M., J.M.L. and I.M.C.) and the National Science Foundation for computational support through TeraGrid/XSEDE allocation MCB070073N (C.F.A.). Funding for D.R.M.M. was provided through a CAPES-Fullbright scholarship. This work was supported in part by the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program, Office of the Director, NIH (C.A.B.) and the NIH Intramural Research Program (NIDDK). Part of the computational work was performed on the DRACO GPU cluster in the Department of Physics at Drexel University (NSF AST-0959884).

Abbreviations

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- STD NMR

saturation transfer difference nuclear magnetic resonance

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PBST

phosphate buffered saline with Tween

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- SA

streptavidin

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- OPD

o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride

- OD

optical density

- COSY

correlation spectroscopy

- HOHAHA

homonuclear Hartmann-Hahn spectroscopy

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- NaOH

sodium hydroxide

- HCl

hydrochloric acid

- MD

molecular dynamics

- Fab

antigen-binding fragment

- PDB

protein databank

- PC

principal component

- PCA

principal component analysis

- RMSD

root-mean squared distance/deviation

- WT

wild-type

- IC50

half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- SASA

solvent accessible surface area

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Tables S1-S3 and Figures S1-S5. CHARMM force field parameters for triazole. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Poignard P, Saphire EO, Parren PW, Burton DR. gp120: Biologic aspects of structural features. Annual review of immunology. 2001;19:253–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doms RW. Beyond receptor expression: the influence of receptor conformation, density, and affinity in HIV-1 infection. Virology. 2000;276:229–237. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallo SA, Finnegan CM, Viard M, Raviv Y, Dimitrov A, Rawat SS, Puri A, Durell S, Blumenthal R. The HIV Env-mediated fusion reaction. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2003;1614:36–50. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Didigu CA, Doms RW. Novel approaches to inhibit HIV entry. Viruses. 2012;4:309–324. doi: 10.3390/v4020309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilton JC, Doms RW. Entry inhibitors in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Antiviral research. 2010;85:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkhout B, Eggink D, Sanders RW. Is there a future for antiviral fusion inhibitors? Current opinion in virology. 2012;2:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore JP, Kuritzkes DR. A piece de resistance: how HIV-1 escapes small molecule CCR5 inhibitors. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2009;4:118–124. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283223d46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Si Z, Madani N, Cox JM, Chruma JJ, Klein JC, Schon A, Phan N, Wang L, Biorn AC, Cocklin S, Chaiken I, Freire E, Smith AB, 3rd, Sodroski JG. Small-molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 entry block receptor-induced conformational changes in the viral envelope glycoproteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:5036–5041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307953101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]