Abstract

Objective

Development of an effective therapy to slow the inexorable progression of Parkinson disease requires a reliable, objective measurement of disease severity. In the present study, we compare pre-synaptic PET tracer uptake in the substantia nigra (SN) to cell loss and motor impairment in MPTP non-human primates.

Methods

Pre-synaptic PET tracers, 6-[18F]-fluorodopa (FD), [11C]-2β-methoxy-3β-4-fluorophenyltropane (CFT), and [11C]-dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) were used to measure specific uptake in the SN and striatum before and after a variable dose of MPTP in non-human primates. These in vivo PET-based measures were compared with motor impairment, as well as post-mortem tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cell counts and striatal dopamine concentration.

Results

We found the specific uptake of CFT and DTBZ in the SN each had a strong, significant correlation with dopaminergic cell counts in the SN (R2 = 0.77, 0.53 respectively, p < .001) but FD did not. Additionally, CFT and DTBZ specific uptake in the SN each had a linear relationship with motor impairment (rs = −0.77, −0.71 respectively, p < .001) but FD did not.

Interpretation

Our findings demonstrate that PET measured binding potentials for CFT and DTBZ for a midbrain volume of interest targeted at the SN provide faithful correlates of nigral neuronal counts across a full range of lesion severity. Since these measures correlate with both nigral cell counts and parkinsonian ratings, we suggest that these SN PET measures are relevant biomarkers of nigrostriatal function.

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder associated with loss of the dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway. The hallmark motor manifestations of PD include tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability, the severity of which may reflect loss of nigrostriatal neurons.1 Currently available treatments focus on symptomatic relief, but no therapy has been shown to slow disease progression. To develop such therapy requires an objective measure of disease progression. Molecular imaging of nigrostriatal neurons has been applied for this purpose in multiple studies, but imaging results frequently conflict with clinical endpoints such as changes in the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS).2-5 Recent studies suggest that striatal uptake of presynaptic markers correlate with striatal dopamine but may not reflect loss of nigrostriatal neurons throughout the full range of depletion.6,7 In addition, nigral neuronal loss more closely correlates with clinical parkinsonism measures than striatal dopamine concentration, at least in MPTP treated nonhuman primates1. Therefore, development of molecular imaging markers that reflect nigral neuronal count may provide a more faithful biomarker of nigrostriatal injury.

Positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography combined with different radiotracers have been used to quantify loss in dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons. The first tracer developed was 6-[18F]-fluorodopa (FD), which is converted to 6-[18F]-fluorodopamine by dopa decarboxylase that is mostly contained in presynaptic neurons in the striatum.8 Subsequently developed radiotracers reflect other pre-synaptic sites, such as the dopamine transporter (DAT) and presynaptic vesicular monoamine transporter-2(VMAT-2).9,10,11 A variety of labeled tracers, primarily cocaine analogs, bind to DAT.12 In this study we use [11C]-2β-methoxy-3β-4-fluorophenyltropane (CFT) which binds to DAT, and [11C]-dihydrotetrabenazine which binds to VMAT-2.13,14 Previous studies primarily focused on measures of striatal terminal fields of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons, which may not reflect nigral cell loss or clinical behavior.1,7 However, a recent PET study using a DAT radioligand, 2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-nortropane ([18F]-FENCT), in non-human primates reported data from 3 monkeys that midbrain uptake may correlate with post-mortem stereologic counts of nigral neurons.11

The present study investigates the relationship of PET measured specific uptake for DTBZ, CFT, and FD in the midbrain to nigral neuron counts, striatal dopamine, striatal PET measures, and motor impairment across a wide range of lesion severity in MPTP-treated primates. The in vitro measures, striatal PET measures, and the motor ratings have been reported.1,6,7

Methods

Subjects

Sixteen male macaques between the ages of 3.5 and 6.5 years old (mean = 5.4±1.0 years) were studied. The minimum number of animals necessary was used and animal care followed National Institutes of Health guidelines. All work was conducted at the Washington University in St. Louis Nonhuman Primate Facility with the approval of its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were housed in facilities with 12-hour dark and light cycles, given access to food and water ad libitum, and provided with a variety of activities for psychological enrichment.

Study Design

Each monkey had an MRI and two baseline PET scans using FD, DTBZ, and CFT. Animals were trained to perform several behavioral tasks to assess motor abilities, and ratings were done before and after MPTP. A variabledose of MPTP (0 to 0.31 mg/kg) was infused via the right internal carotid artery.6,15,16 Eight weeks later, two PET scans were repeated with each of the tracers. Following the final PET, the animal was euthanized and the brain was rapidly removed. Brain tissue was then prepared, stained, and counted. Animals were never given dopaminergic drugs and were able to care for themselves throughout the study.

Behavioral Measures

Each monkey was trained using positive conditioning to perform various behavioral tasks consisting of walking and reaching for fruit. After the monkey was trained on all tasks, behavioral sessions were recorded at the same time of day three times a week before and after MPTP. Each video was rated by an observer blinded to MPTP dose using a scale developed and validated for non-human primate studies.1,17 The final parkinsonism score was used for analyses, as motor impairment was stable for at least 4-5 weeks prior to euthanasia.1

Neuroimaging

PET Scans

PET scans were done with the Siemens (Knoxville, TN) MicroPET Focus 220 scanner as described.15,18 Radiotracer was injected intravenously over 60 seconds (FD: 3-10 mCi, CFT: 7-10 mCi, DTBZ: 7-10 mCi) followed by acquisition for as long as 120 minutes with three 1-minute frames, four 2-minute frames, three 3-minute time frames, and twenty 5-minute time frames for all tracers. Emission data were corrected for attenuation, scatter, randoms and deadtime. The reconstructed resolution was < 2.0 mm in all planes.18

MR-defined Volumes of Interest (VOIs)

Primates underwent T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition with gradient echo (MP-RAGE) and T2-weighted turbo spin-echo (TSE) MRI scans using a 3T MAGNETOM Trio System (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) prior to MPTP that were used to define VOIs.15 VOIs were drawn on pre-MPTP T1-weighted MR images. The SN, caudate, and putamen were outlined on transverse slices throughout the extent of the structures. Caudate and putamen regions were summed to form a striatal region of interest. The SN region (SN pars compacta and parts of SN pars reticulata) was identified as the band immediately dorsal to the hypo-intense SNr and ventral to the red nucleus. The medial border of the SN region was the oculomotor nerve fibers or the interpeduncular cistern when not at the level of the oculomotor nerve with the SNr also serving as the lateral border. We used the superior colliculus as the rostral border and pons as the caudal border of SN region. Top and bottom slices were removed to minimize spillover from neighboring regions. Although this SN region was based on anatomical landmarks it likely includes non-SN pars compacta tissue and regions ranged from 15-30 voxels (1.9 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm3) across subjects. The outline of the SN follows an approach used for humans.19 A pair of hemi-cylinders drawn on either side of the midline in the occipital cortex served as a reference region (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The midbrain VOIs outline in red and white on a transverse T1-weighted slice with high contrast. The regions surround the slight hyper-intensity between the hypo-intense reticulata (SNr) and red nucleus (RN). The medial border is the relatively hyper-intense oculomotor nerves just dorsolateral to the interpeduncular cistern (IC), and the lateral border is the SNr.

The MP-RAGE was co-registered to the baseline DTBZ scan using a voxel-based vector gradient co-registration.20 This procedure generated a transformation matrix from MP-RAGE space to the initial DTBZ PET scan, and this matrix transformed the VOIs to PET space. All other PET scans were individually co-registered to the first DTBZ scan also using the vector gradient method.

Tissue activity curves were extracted for each VOI, and the non-displaceable binding potential (BPND) was calculated for CFT and DTBZ according to the tissue reference method using data from 15-115 minutes after injection for CFT and 15-60 minutes for DTBZ and the influx constant (Kocc) for FD using data from 24-94 minutes after injection.21-24 Occipital uptake was used as the input function for all of these calculations.7 For each scan, a right/left ratio was calculated for BPND and Kocc. The average ratio of 2 pre-MPTP scans was calculated and used as the baseline tracer uptake. The average ratio of the 2 post-MPTP scans was calculated and used as the post-MPTP tracer uptake.

In Vitro Measures

Animals were euthanized with intravenous pentobarbital two months post-MPTP after the final PET. Brains were removed, processed, and stained as previously reported to obtain stereologic counts of nigral dopaminergic neurons and high performance liquid chromatography-based measures of striatal dopamine.6,25

Statistical Analysis

The injected (right) to control side (left) ratio was calculated for all PET, dopamine and stereology measures. The average post-MPTP right/left BPND or Kocc ratio was termed the post-MPTP BPND or Kocc. Results were analyzed using SPSS (version 18.0.2 IBM, Chicago, IL). Linear regression was performed for each of the PET tracers for both SN and striatal regions with nigrostriatal cell counts, striatal dopamine concentration and motor scores. Each animal contributed a single point in each regression. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

All sixteen animals successfully completed the study. One monkey had severe damage to the midbrain tissue during processing, preventing proper nigral cell counting on this animal. Motor scores for each animal demonstrated a wide range of severity of parkinsonism that stabilized for at least five weeks prior to euthanasia. The motor ratings in most of these animals have been reported.1 There was no differential damage between the caudate and putamen as previously reported.7 CFT and DTBZ BPND provided similar results before and after MPTP, while FD Kocc values were much more variable. At baseline the injected/control side ratios of CFT (t (15) = 0.77, p = 0.45) and DTBZ (t (15) = 0.60, p = 0.55) BPND were not significantly different from 1.0 across animals with relatively low standard deviation (Table 1). Similarly, DTBZ (mean CE = 0.07) and CFT (mean CE = 0.15) BPND injected/control side ratios were relatively stable between the two scans for each animal. Although baseline injected/control side ratios of FD Kocc were not significantly different from 1.0 on average (t (15) = 0.55, p = 0.59) the standard deviation was much higher (Table 1) with poor reproducibility between scans (mean coefficient of error (CE) = 0.35). All in vitro and in vivo measures of dopamine function significantly decreased following MPTP except for FD specific uptake in the SN region (Table 2). After MPTP, the within animal reproducibility remained acceptable for CFT and DBTZ (mean CE = 0.25, 0.09 respectively) but not for FD (mean CE = 0.44, Table 1). Post-MPTP nigral BPND ratio of CFT and DTBZ had a strong, significant correlation with each other (Figure 2, r = 0.88, N = 16, p < 0.001). However, post-MPTP FD Kocc did not correlate with either post-MPTP CFT or DTBZ BPND in the SN (r = 0.48, 0.35 respectively, N = 16, p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Summary of results from 16 monkeys

| Monkey #Number | SN Injected/Control Side Ratio Mean (CE) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFT Pre |

CFT Post |

DTBZ Pre |

DTBZ Post |

FD Pre |

FD Post |

SN Ratio |

DA Ratio |

|

| 1 | 1.06 (.18) | 0.73 (.13) | 0.99 (.04) | 0.72 (.11) | 0.99 (.04) | 0.72 (.12) | 0.73 | 0.50 |

| 2 | 1.05 (.17) | 0.91 (.16) | 0.93 (.06) | 0.86 (.02) | 1.11 (.05) | 0.92 (.22) | 0.81 | 0.86 |

| 3 | 0.95 (.40) | 0.19 (.30) | 0.86 (.02) | 0.43 (.25) | 0.96 (.44) | 1.13 (.50) | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| 4 | 1.11 (.04) | 1.16 (.20) | 0.96 (.10) | 1.00 (.06) | 0.81 (.09) | 1.15 (.37) | 0.78 | 1.07 |

| 5 | 1.17 (.33) | 0.04 (1.77) | 0.96 (.22) | 0.49 (.25) | 0.48 (.74) | 0.71 (.42) | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| 6 | 1.00 (.24) | 1.08 (.06) | 1.03 (.07) | 1.02 (.04) | 0.70 (.48) | 1.24 (.70) | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| 7 | 0.86 (0) | 0.41 (.14) | 0.99 (.10) | 0.63 (.08) | 1.04 (.11) | 0.90 (.48) | NA | 0.04 |

| 8 | 1.25 (.24) | 0.99 (.22) | 1.32 (.18) | 1.21 (.01) | 1.38 (.58) | 0.82 (.97) | 0.68 | 0.37 |

| 9 | 1.20 (.13) | 0.35 (.23) | 1.26 (.04) | 0.80 (.02) | 1.23 (.42) | 0.86 (.38) | 0.47 | 0.02 |

| 10 | 0.77 (.04) | 0.99 (.32) | 0.94 (.05) | 0.98 (.18) | 0.99 (.30) | 1.19 (.43) | 0.88 | 1.03 |

| 11 | 1.06 (.10) | 0.95 (01) | 0.99 (.04) | 0.99 (.03) | 0.91 (.64) | 0.86 (.07) | 0.81 | 0.59 |

| 12 | 0.86 (0) | 0.41 (.14) | 0.99 (.10) | 0.63 (.08) | 1.13 (.45) | 0.67 (.42) | 0.49 | 0.02 |

| 13 | 0.97 (.04) | 0.35 (.03) | 0.86 (.10) | 0.70 (.13) | 1.07 (.09) | 0.85 (.06) | 0.50 | 0.01 |

| 14 | 0.99 (.21) | 0.49 (.08) | 1.09 (.02) | 0.76 (.05) | 1.02 (.35) | 0.93 (.27) | 0.20 | 0.01 |

| 15 | 1.08 (.21) | 0.94 (.17) | 1.09 (.07) | 0.88 (.06) | 0.95 (.60) | 0.93 (1.0) | 0.87 | 0.64 |

| 16 | 1.01 (.06) | 0.89 (0) | 1.03 (.03) | 1.04 (.07) | 0.76 (.22) | 1.03 (.56) | 0.94 | 0.86 |

|

| ||||||||

| 1.02 (.15) | 0.68 (.25) | 1.02 (.08) | 0.82 (.09) | 0.97 (.35) | 0.93 (.44) | 0.64 | 0.43 | |

Mean pre- and post-MPTP BPND and Kocc values for each of the16 monkeys. Co-efficient of error (CE) is given in parentheses. Values in the average row are the mean BPND or Kocc and the mean CE in parentheses. Post-mortem cell count ratio (SN ratio) and striatal dopamine concentration ratio (DA ratio) are the injected/control side ratio.

Table 2.

Summary of pre- and post-MPTP PET measures in the nigra and striatum

| Pre-MPTP Mean (SD) |

Post-MPTP Mean (SD) |

T- score |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigral CFT BP | 1.02 (0.13) | 0.68 (0.35) | −3.75 | .002 |

| Nigral DTBZ BP | 1.02 (0.12) | 0.82 (0.21) | −4.22 | .001 |

| Nigral FD Kocc | 0.97 (0.21) | 0.93 (0.17) | 0.50 | 0.62 |

| Striatal CFT BP | 0.99 (0.04) | 0.42 (0.41) | −5.32 | <.001 |

| Striatal DTBZ BP | 1.00 (0.04) | 0.45 (0.40) | −5.31 | <.001 |

| Striatal FD Kocc | 1.00 (0.05) | 0.54 (0.38) | −4.57 | <.001 |

Mean pre- and post-MPTP BPND or Kocc values for all monkeys. Standard deviations across monkeys are reported in parentheses. It should be noted that post-MPTP standard deviations are expected to be high due to variable doses of MPTP. T-test value and p-value are results of comparing means of post- and pre-MPTP measures.

Figure 2.

The relationship between injected/control side MPTP BPND of CFT and DTBZ. Each data point represents one monkey and the trend line is the linear fit of the data. There was a wide distribution of data and tight linear relationship.

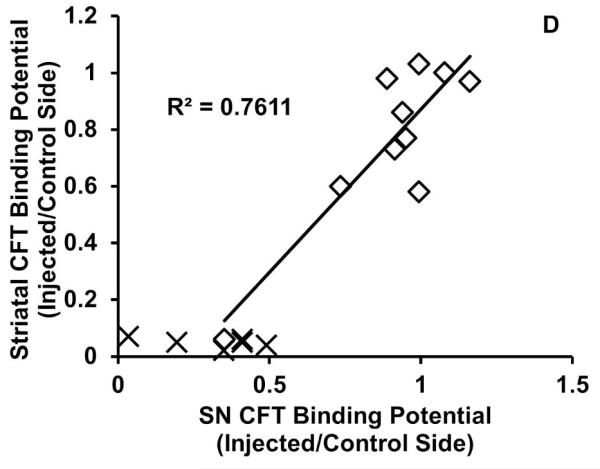

We then compared the SN post-MPTP BPND (or Kocc) for each radiotracer with in vivo and vitro measures of nigrostriatal neurons and striatal dopamine function. SN BPND for CFT (r = 0.87, N = 16, p < 0.001) and DTBZ (r = 0.73, N = 16, p = 0.001) significantly correlated with residual nigral neurons throughout the range of cell loss (Figure 3a-c) but FD had only a modest, trend-level correlation (r = 0.44, N = 16 p = 0.09). For CFT and FD, post-MPTP BPND (or Kocc) in the SN only correlated significantly with residual striatal dopamine when less than 50% of nigral neurons were lost, while DTBZ did not at any level of loss: CFT r = 0.80, n = 10, p = 0.006); DTBZ r = 0.38, n = 10 p = 0.28; and FD (Kocc) r = 0.74, n = 10, p = .01, Figure 4a-c). Comparisons of the post-MPTP BPND for CFT, DTBZ, and FD (Kocc) in the SN with the same measures in the striatum (striatal measures were previously reported7) revealed a pattern similar to that of the comparison with in vitro striatal dopamine measures. Specifically BPND in the SN only correlated with BPND of CFT (r = 0.87, n = 10, p = 0.001), DTBZ (r = 0.55, n = 10, p = 0.10), or FD (Kocc, r = 0.67, n = 10 p = 0.03) in the striatum when less than 50% of the nigral neurons were lost. At higher levels of nigral neuronal loss all striatal measures were near 0 (Figure 4d-f).

Figure 3.

The relationship between CFT (A),DTBZ (B), and FD (C) injected/control side BPND (or Kocc) in the SN and injected/control side ratio of TH+ neurons in the SN. Each data point represents one monkey and the trend lines are the linear fits of the data. CFT and DTBZ exhibited a tight linear correlation with residual cells in the SN.

Figure 4.

The relationship between injected/control side SN BPND or Kocc for each tracer and injected/control side striatal dopamine concentration (a-c) or striatal BPND or Kocc of the same tracer (d-f). Each data point represents one monkey. Trend lines are the linear fit of data points other than X, which were primates with ≥50% cell loss. Both striatal dopamine and striatal PET measures had a flooring effect after >50% cell loss, and SN BPND only showed a linear fit when <50% nigral cell loss occurred.

Finally, we compared the post-MPTP PET SN measures with clinical ratings of parkinsonism: CFT (rS = −0.77, N = 16, p < 0.001) and DTBZ (rS = −0.71, N = 16, p = 0.001) BPND in SN correlated with motor score (Figure 5) but FD did not (rs = −0.43, N = 16, p = 0.10).

Figure 5.

The relationship between CFT (top) and DTBZ (bottom) injected/control side BPND in the SN and final motor score. Each data point represents one monkey and the trend lines are the linear fits of the data. Both CFT and DTBZ had a tight linear relationship with motor scores across a wide range of lesion severity and motor impairment.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that PET measured binding potentials for CFT (for DAT) and DTBZ (for VMAT2) for a VOI targeted at the SN provide faithful correlates of nigral neuronal counts across a full range of lesion severity. Since these PET measures also correlate with parkinsonian ratings, we suggest that CFT and DTBZ binding potentials in SN provide relevant biomarkers of nigrostriatal damage. SN uptake of FD, however, failed to correlate with either nigral dopaminergic cell loss or motor impairment. These findings sharply contrast with striatal uptake of these tracers that only correlate with either nigral cell counts or clinical motor behavior when nigral neuronal loss does not exceed 50%. These SN PET measures have important implications for potential application to human studies of PD.

DTBZ and CFT BPND in the SN correlate with each other but not FD or striatal uptake

DTBZ and CFT binding potentials in the SN correlate strongly with each other. However, nigral FD specific uptake does not correlate with either DTBZ or CFT BPND. This differs from the striatum, where a recent study found a significant correlation between the DTBZ, CFT, and FD specific uptake.7 This discrepancy is likely due to low signal to noise ratio despite using a high resolution MicroPET as manifested in high scan to scan variability for nigral FD uptake. The nigral uptake of FD may be too low due to relatively low levels of dopa-decarboxylase in SN compared to the much higher levels in striatum. Without sufficient decarboxylase to convert FD to radiolabeled dopamine, it might not be possible to achieve a sufficiently high signal to noise ratio for detection.8 Other factors also may contribute to this limitation of FD. The imaging characteristics of FD are inferior to DTBZ and CFT with less brain penetration and lower target to background ratios. The preferential nigral accumulation of CFT and DTBZ also may reflect the anatomical location of DAT and VMAT2 in dendritic fields of nigrostriatal neurons.26,27 Another tracer of dopamine synthesis like [18F]-fluorometatyrosine (FMT) also reflects decarboxylase activity but is not subjected to O-methylation. FMT may not be as specific for dopaminergic neurons as FD.28-30 However, PET measures of midbrain uptake of FMT have been done in nonhuman primates and humans.31-32 FMT uptake in SN appeared to increase 3 weeks after unilateral MPTP in monkeys but this could reflect either increased dopa-decarboxylase activity at a time earlier than we examined in our study or a change in indolamine synthesis.30,31 Furthermore, the FMT measures have not yet been validated by comparison of quantitative SN PET imaging with quantitative stereological cell counts in the nigra.31 Nevertheless, either FD or another radiotracer like FMT reflects different components of nigral dopaminergic neurons from either a DAT or VMAT2 tracer, yet our data suggest that midbrain uptake of FD in monkeys does not provide a faithful representation of nigral TH cell counts.32

DTBZ and CFT BPND in the SN has a linear relationship with residual TH+ neurons

Previous neuroimaging studies have attempted to assess the ability of various tracers to reflect the degree of dopaminergic neuron loss in the SN. Many of these studies have focused on striatal PET measures with limited success.5,33 The present study suggests that PET measures should focus on specific tracer uptake in the SN, rather than the striatum. These results support previous findings suggesting that DAT radioligand binding linearly correlates with residual nigral dopamine cells in MPTP primates.11 However, the previous study was limited by a small number of subjects and limited range of nigral cell loss. The additional subjects and wider range of dopaminergic loss in our study offers additional evidence that nigral specific binding of a DAT marker reflects the number of nigral dopamine neurons.

Nigral DTBZ and CFT BPND’s linearly correlated with SN dopaminergic neuronal counts, but not with striatal dopamine or striatal PET measures. Nigral CFT BPND correlates with striatal measures (in vitro dopamine and in vivo PET) only with nigral cell loss of less than 50%. We did not demonstrate such a correlation between nigral DTBZ BPND and striatal measures but this most likely was due to one subject with considerably higher SN DTBZ BPND on the injected compared to the control side before and after MPTP. In general, at higher degrees of cell loss, the striatal measures reach a nadir with a flooring effect. These findings further support the notion that terminal field measures in the striatum do not consistently reflect in vivo nigral PET measures of CFT or DTBZ nor in vitro measures of nigral cell counts throughout a full range of nigral cell loss.

DTBZ and CFT BPND in the SN correspond with degree of motor impairment

Nigral DTBZ and CFT BPND’s strongly correlate with degree of motor impairment across a full range of clinical severity. We previously demonstrated ratings of parkinsonism in these animals correlate better with in vitro nigral dopaminergic cell counts than striatal dopamine concentration.1 Thus, our findings indicate that DAT and VMAT2 concentrations in the SN of MPTP primates have a linear relationship with degree of motor impairment in the absence of dopaminergic treatment in MPTP primates. The effects of medications on these SN measures remain to be determined.

Limitations and Future Studies

While these results provide encouragement that PET measures of nigral uptake of DTBZ and CFT could be used as biomarkers of nigrostriatal injury providing an objective metric of PD progression for clinical trials, there are several important limitations of this present study that should be further investigated. We only examined the relationship between the radiotracers and in vitro measures at 2 months post-MPTP. It will be important to examine these relationships at multiple time points to determine if changes in these relationships occur at different times following MPTP. This will also allow comparison of the rate of loss between CFT, DTBZ, and in vitro dopamine measures over time. The long-term and short-term effects of common dopaminergic medications or any therapeutic intervention on DTBZ and CFT BPND in the SN must be determined; otherwise these measures might not provide a faithful biomarker of nigrostriatal neurons for a specific clinical trial.33-35 It is also important to note that while the MPTP model provides a model of nigrostriatal injury, there are differences in the neuropathology between MPTP and PD which limit a direct comparison of these data to the neuropathologic changes in PD.36,37 Finally, the midbrain uptake of these biomarkers could provide a viable metric for PD disease progression but like other moelcular imaging approaches, it may have limited diagnostic utility when compared to current clinical assessments.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH (NS058714, NS069746, NS41509, NS075321); Michael J Fox Foundation; Murphy Fund; American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Center for Advanced PD Research at Washington University; Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function; Hartke Fund; Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation (Elliot Stein Family Fund for PD Research & the Parkinson Disease Research Fund). We thank Christina Zukas, Darryl Craig, and Terry Anderson for expert technical assistance. All authors report no financial interests or potential conflicts of interests.

References

- [1].Tabbal SD, Tian LL, Karimi MK, Brown CA, et al. Low nigrostriatal reserve for motor parkinsonism in nonhuman primates. Exp Neuro. 2012;237:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].The Parkinson Study Group Levodopa and the Progression of Parkinson’s Disease. NEJM. 2004;351:2498–2508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Whone AL, Watts RL, Stoessl AJ, Davis M, et al. Slower progression of Parkinson’s disease with ropinirole versus levodopa: The REAL-PET study. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:93–101. doi: 10.1002/ana.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lang AE, Gill S, Patel NK, Lozano A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor infusion in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:459–466. doi: 10.1002/ana.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ravina B, Eidelberg D, Ahlskog JE, Albin RL, et al. The role of radiotracer imaging in Parkinson disease. Neurol. 2005;64:208–215. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149403.14458.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tian LL, Karimi MK, Loftin SK, Brown CA, et al. No Differential Regulation of Dopamine Transporter (DAT) and Vesicular Monoamine Transporter 2 (VMAT2) Binding in a Primate Model of Parkinson Disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Karimi MK, Brown CA, Tian LL, Loftin SK, et al. Validation of Nigrostriatal Positron Emission Tomography Measures: Critical Limits. Ann Neruol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ana.23798. DOI: 10.1002/ana.23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Martin WW, Perlmutter JS. Assessment of fetal tissue transplantation in Parkinson’s disease: Does PET play a role? Neurol. 1994;44:1777–1780. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.10.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bohnen NI, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Wernette KA, et al. Positron emission tomography of monoaminergic vesicular binding in aging and Parkinson disease. J. Cereb Blood Metab. 2006;26:1198–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen M-K, Kuwabara H, Zhou Y, Adams RJ, et al. VMAT2 and dopamine neuron loss in a primate model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2008;105:78–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Masilamoni G, Votaw J, Howell L, Villalba RM, et al. 18 F-FECNT: Validation as PET dopamine transporter ligand in parkinsonism. Exp Neuro. 2010;226:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Marek KL, Seibyl JP, Zoghbi SS, Zea-Ponce Y, et al. [123I] beta-CIT/SPECT imaging demonstrates bilateral loss of dopamine transporters in hemi-Parkinson’s disease. Neurol. 1996;46:231–237. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Vander Borght TM, Karlamangla A, et al. Kinetic Evaluation of [11C]Dihydrotetrabenazine by Dynamic PET: Measurement of Vesicular Monoamine Transporter. J Cereb Blood Metabl. 1996;16:1288–1299. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Brownell A-L, Elmaleh DR, Metlzer PC, Shoup TM, et al. Cocaine congeners as PET imaging probes for dopamine terminals. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1186–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tabbal SD, Mink JW, Antenor JA, Carl JL, et al. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced acute transient dystonia in monkeys associated with low striatal dopamine. Neurosci. 2006;141:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nishant K, Lee JJ, Perlmutter JS, Derdeyn CP. Cervical Carotid and Circle of Willis Arterial Anatomy of Macaque Monkeys: A Comparative Anatomy Study. Anat Rec. 2009;292:976–984. doi: 10.1002/ar.20891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Perlmutter JS, Tempel LW, Black KJ, Parkinson D, Todd RD. MPTP induces dystonia and parkinsonism: clues to the pathophysiology of dystonia. Neurol. 1997;49:1432–1438. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tai Y-C, Ruangma A, Newport DF, Chow PL, et al. Performance evaluation of the microPET focus: A third-generation microPET scanner dedicated to animal imaging. J Nuc Med. 2005;46:455–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Foster ER, Black KJ, Antenor J, Perlmutter JS, Hershey T. Motor asymmetry and substantia nigra volume are related to spatial delayed response performance in Parkinson disease. Brain Cognition. 2008;67:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rowland DJ, Garbow JR, Laforest R, Snyder AZ. Registration of [18F]FDG microPET and small-animal MRI. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Logan J. Graphical analysis of PET data applied to reversible and irreversible tracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sossi V, Holden JE, Chan G, Krzywinski M, et al. Analysis of four dopaminergic tracers kinetics using two different tissue input function methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:653–660. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1983;3:1–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Patlak CS, Blasberg RG. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Metab. 1985;5:584–590. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Karimi MK, Carl JL, Loftin SK, Perlmutter JS. Modified high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection method for plasma measurement of levodopa, 3-O-methyldopa, dopamine, carbidopa and 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl acetic acid. J Chromatogr B. 2006;836:120–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hersch SM, Yi H, Heilman CJ, Edwards RH, Levey AI. Subcellular localization and molecular topology of the dopamine transporter in the striatum and substantia nigra. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:211–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nirenberg MJ, Chan J, Liu Y, Edwards RH, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural Localization of the Vesicular Monoamine Transporter-2 in Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons: Potential Sites for Somatodendritic Storage and Release of Dopamine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4135–4145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nahmias C, Wahl L, Chirakal R, Firnau R, Garnett ES. A probe for intracerebral aromatic amino-acid decarboxylase activity: Distribution and kinetics of [18F]6-fluoro-L-m-tyrosine in the human brain. Mov Disord. 1995;10:298–304. doi: 10.1002/mds.870100312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Barrio JR, Huang S-C, Yu D-C, Melega WP, et al. Radiofluorinated L-m-Tyrosines: New In-Vivo Probes for Central Dopamine Biochemistry. J Cereb Blood Metab. 1996;16:667–678. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199607000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brown WD, DeJesus OT, Pyzalski RW, Roberts AD, et al. Localization of trapping of 6-[18F]fluoro-L-m-tyrosine, an aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase tracer for PET. Synapse. 1999;34:111–123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199911)34:2<111::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Eberling JL, Bankiewicz KS, Jordan S, VanBrocklin HF, Jagust WJ. PET studies of functional compensation in primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2727–2733. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199708180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dang LC, O’Neil JP, Jagust WJ. Genetic effects on behavior are mediated by neurotransmitters and large-scale neural networks. Neuroimage. 2012;66:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Michell AW, Lewis JG, Foltynie T, Barker RA. Biomarkers and Parkinson’s Disease. Brain. 2004;127:1693–1705. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dorsey ER, Holloway RG, Ravina BM. Biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Nuerother. 2006;6:823–831. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.6.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fahn S, Oakes D, Shoulson I, Kieburtz K, et al. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s disease. NEJM. 2004;351:2498–508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Meissner W, Prunier C, Guilloteau D, Chalon S, et al. Time-course of nigrostriatal degeneration in a progressive MPTP-lesioned macaque model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;28:209–218. doi: 10.1385/MN:28:3:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]