Abstract

Progressive facial atrophy or Parry-Romberg syndrome is characterized by slowly progressive facial atrophy involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, cartilage and bony structures. Apart from facial atrophy, it can be associated with diverse clinical manifestations including headache, partial seizures, trigeminal neuralgia, cerebral hemiatrophy and ocular abnormalities. The exact etiology is unknown although sympathetic system dysfunction, autoimmune disorders, focal scleroderma, trauma and genetic factors have been postulated. We hereby report a patient having marked left-sided facial atrophy and wasting of the tongue. Such an extensive wasting is not previously reported in the literature.

Keywords: Facial atrophy, hemiatrophy, Parry-Romberg syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Parry-Romberg syndrome is characterized by slowly progressive atrophy of the soft tissues of essentially half the face. It is due to gradual wasting of subcutaneous fat, sometimes accompanied by atrophy of skin, cartilage, bone and muscle.[1] It is a chronic disorder leading to facial deformity and can be associated with varied neurological manifestations, which include migrainous headache, lancinating pains of trigeminal neuralgia and epileptic seizures.[2] The pathogenesis of this disfiguring disorder is debatable, although sympathetic dysfunction, autoimmune mechanism, focal scleroderma and infections have been postulated.[3] In this case report, we intended to present middle-aged female, who manifested with extensive left-sided facial atrophy with severe tongue wasting. Such a high degree of facial atrophy is not reported in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old female presented with gradually progressive left-sided facial atrophy for the last 30 years. She also complained of intermittent left-sided headache for the last 8–9 years, which was throbbing, pulsatile with photophobia, phonophobia with history of visual auras. She had continuous tearing and redness of left eye since 3 years. There was no history of extraction of teeth, local trauma, seizures or lancinating pain suggestive of trigeminal neuralgia. The patient denied history of joint pains, rash, dyspnea, double vision and neurologic deficits in the extremities. Family history was non-contributory.

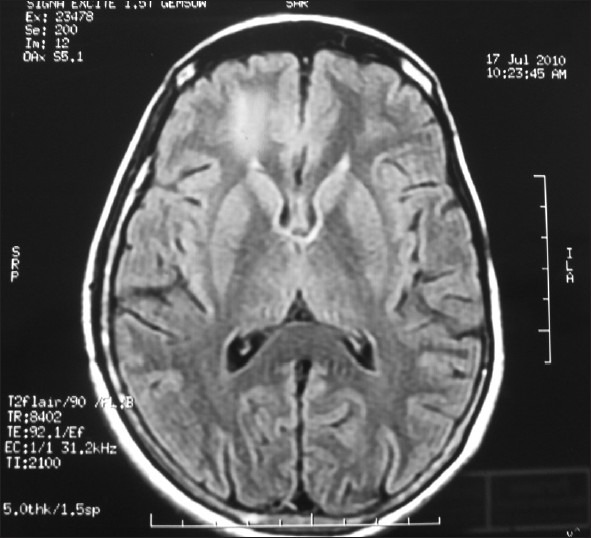

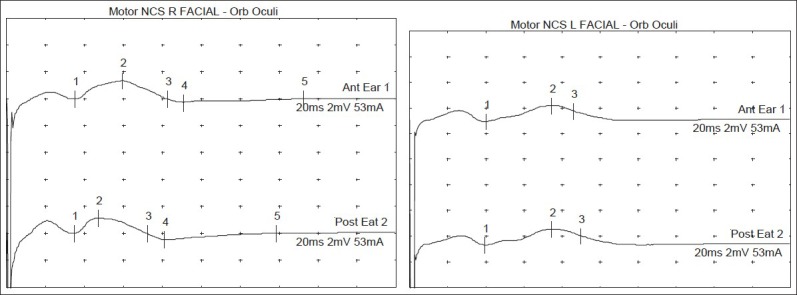

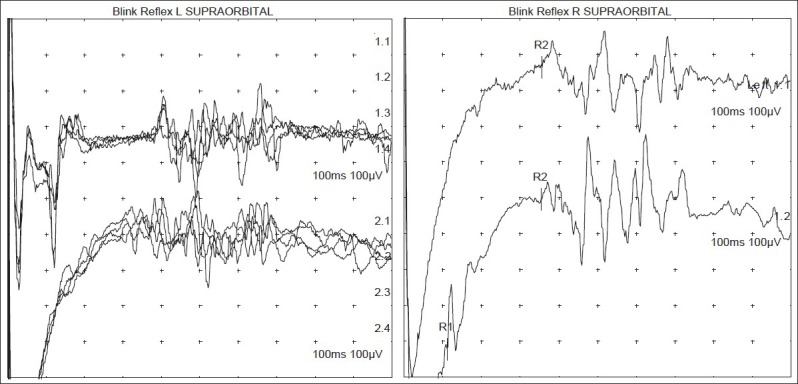

On examination, marked left-sided facial atrophy was present [Figure 1]. Oral cavity assessment disclosed left-sided tongue atrophy [Figure 2]. Ocular examination revealed enophthalmos and uveitis in left eye. The skin over left lower face had bluish hue. Rest of neurological examination was unremarkable. The investigations, including hematological parameters, blood sugar, serum creatinine, blood urea and liver function test revealed normal results. The C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were not raised. The autoimmune markers, comprising antinuclear antibody, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody, anticardiolipin antibody and rheumatoid factor were non-reactive in sera. The viral studies for Epstein Barre virus, cytomegalovirus, dengue virus, herpes simplex virus and Japanese encephalitis virus showed negative results. Electroencephalography was reported to be normal. Magnetic resonance imaging of cranium did not demonstrate any abnormality [Figure 3]. Facial nerve stimulation at anterior ear on both sides revealed minor differences in latency and amplitudes [Figure 4]. Blink reflex on stimulation of supraorbital nerves showed insignificant differences of R2-R1, on left side 27.95 ms, while on right side 24.20 ms [Figure 5]. The clinical description and laboratory evaluation suggested the diagnosis of facial atrophy of Romberg and migraine with aura. The patient was prescribed propranolol 40 mg twice a day, flunarizine 10 mg/day as prophylactics for migraine along with abortive medications for control of acute headache. The patient was not willing for facial reconstructive surgery. On follow up after 6 months, her frequency of headache was significantly decreased.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the patient revealing extensive left-sided facial atrophy

Figure 2.

Photograph showing left-sided tongue atrophy

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging cranium T2 FLAIR image demonstrated normal study

Figure 4.

Facial nerve stimulation on both sides revealing minor differences in latency and amplitudes

Figure 5.

No gross abnormality on blink reflex

DISCUSSION

Facial atrophy of Romberg is a rare neurological disorder characterized by gradually developing facial atrophy involving skin, soft tissue, cartilage and bony structures. It can also be accompanied by atrophy of other parts of body. Duymaz et al. in their paper reported a patient of unusual combination of contralateral lower extremity atrophy with Parry-Romberg syndrome.[4] In our patient there was longstanding history of progressive facial atrophy and migraine with aura.

The neurological manifestations commonly associated with facial atrophy syndrome are migraine, trigeminal neuralgia, partial seizures and occasionally neurological deficits in extremities and abnormal movements.[2] A young male was reported of severe facial pain associated with progressive facial atrophy. This patient responded dramatically to carbamazepine, justifying the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia.[5] In other report, a patient was diagnosed as Parry-Romberg syndrome, who presented with status migrainous.[6] We hypothesized that it could be involvement of trigemino-vascular system which can explain causation of headache as well as facial atrophy.

The etiopathogenetic mechanism for progressive facial atrophy is controversial. The literature analysis revealed sympathetic dysfunction, local trauma, localized scleroderma, autoimmunity and infection particularly Borrelia burgdorferi to be causative factors.[7] In our patient we tried to find out involvement of trigemino-facial pathway and brainstem with the help of facial nerve stimulation and blink reflex but the results were inconclusive. Also our patient had no evidence of linear scleroderma and connective tissue disorder.

The findings on magnetic resonance imaging of cranium depicted in a study were either ipsilateral or contralateral intracerebral atrophy and white matter hyperintensities.[8] Our patient had no abnormalities on MRI (Cranium) but there was significant tongue atrophy and left-sided enophthalmos. Bandello et al. in their case of Parry-Romberg syndrome did fluoroangiography and echography. They inferred that enophthalmos is caused not only by progressive fat atrophy but also by shrinkage of the eyeball and thinning of the extraocular muscles.[9]

The treatment of this disorder is by taking care of associated conditions like prophylactic medications for migraine, antiepileptic drugs for seizures and carbamazepine for trigeminal neuralgia. The facial reconstructive surgery with graft of autologous fat can be performed after abatement of active disease.[10]

CONCLUSION

We report a patient of severe left-sided facial atrophy with tongue wasting. This case also highlights coexistent migraine with aura with responsiveness to prophylactic medications. We also attempted to explore facial and trigeminal nerve involvement by performing neurophysiological studies, although results are inconclusive.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Rogers BO. Progressive facial hemiatrophy: Romberg's disease: A review of 772 cases. Proc 3d Int Cong Plast Surg. Excerpta Medica ICS. 1964;66:681–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Restivo DA, Milone P. Teaching NeuroImages: Progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome) with ipsilateral cerebral hemiatrophy. Neurology. 2010;74:e11. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ca00af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cory RC, Clayman DA, Faillace WJ, McKee SW, Gama CH. Clinical and radiologic findings in progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome) AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:751–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duymaz A, Karabekmez FE, Keskin M, Tosun Z. Parry-Romberg syndrome: Facial atrophy and its relationship with other regions of the body. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:457–61. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31818bed6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar AA, Kumar RA, Shantha GP, Aloogopinathan G. Progressive hemi facial atrophy - Parry Romberg syndrome presenting as severe facial pain in a young man: A case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6776. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menascu S, Padeh S, Hoffman C, Ben-Zeev B. Parry-Romberg syndrome presenting as status migrainosus. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40:321–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de saber morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: A retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;65:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moko SB, Mistry Y, Blandin de Chalain TM. Parry-Romberg syndrome: Intracranial MRI appearances. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:321–4. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandello F, Rosa N, Ghisolfi F, Sebastiani A. New findings in the Parry-Romberg syndrome: A case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2002;12:556–8. doi: 10.1177/112067210201200620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterodimas A, Huanquipaco JC, de Souza Filho S, Bornia FA, Pitanguy I. Autologous fat transplantation for the treatment of Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:424–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]