Abstract

Pyogenic granuloma is a commonly occurring inflammatory hyperplasia of the skin and oral mucosa. It is not associated with pus as its name suggests and histologically it resembles an angiomatous lesion rather than a granulomatous lesion. It is known by a variety of names such as Crocker and Hartzell's disease, granuloma pyogenicum, granuloma pediculatum benignum, benign vascular tumor and during pregnancy as granuloma gravidarum. This tumor like growth is considered to be non-neoplastic in nature and it presents itself in the oral cavity in various clinical and histological forms. Due to its frequent occurrence in the oral cavity, especially the gingiva, this article presents a case report of a large pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva and its management, reviews the literature and discusses why the term “pyogenic granuloma” is a misnomer.

Keywords: Etiology, gingiva, inflammatory hyperplasia, lobular capillary hemangioma, misnomer, non-lobular capillary hemangioma, oral cavity, pyogenic granuloma, recurrence, skin, treatment

INTRODUCTION

In 1844, Hullihen[1] described the first case of pyogenic granuloma in English literature. In 1897, pyogenic granuloma in man was described as “botryomycosis hominis.”[2] Hartzell[3] in 1904 is credited with giving the current term of “pyogenic granuloma” or “granuloma pyogenicum.” It was also called a Crocker and Hartzell's disease.[3] Angelopoulos[4] histologically described it as “hemangiomatous granuloma” due to the presence of numerous blood vessels and the inflammatory nature of the lesion. Cawson et al.,[5] in dermatologic literature have described it as “granuloma telangiectacticum” due to the presence of numerous blood vessels seen in histological sections. They described two forms of pyogenic granulomas, the lobular capillary hemangioma (LCH) and the non-lobular capillary hemangioma (non-LCH). Pyogenic granulomas commonly occur on the skin or the oral cavity but seldom in the gastrointestinal tract.[6]

Different investigators have suggested varied etiologic factors, which lead to the formation of pyogenic granuloma of the skin and oral cavity. Chronic low grade trauma,[7] physical trauma,[8] hormonal factors,[9] bacteria, viruses[10] and certain drugs[11] have been implicated as causative factors in the development of pyogenic granulomas. Oral pyogenic granulomas show a predilection for the gingiva, accounting for 75% of the cases.[12] Local irritants such as calculus, foreign material in the gingiva[8] and poor oral hygiene[7] are the precipitating factors.

In this article, we have presented a case report of a large pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva in a 22-year-old male patient who presented with a localized tumor like enlargement in the upper right quadrant of the jaw. We have also reviewed the literature and discussed the present case with reference to the same and have highlighted why the term pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer.

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old male reported to the Department of Periodontics, complaining of a swelling in the upper right jaw region, which caused discomfort while eating. The patient reported that he noticed the swelling 2 years ago, which was painless and gradually increased in size, during this period he had visited a medical doctor who had given him gum paint for application. He had stopped brushing the area due to bleeding from the area.

On extraoral examination, there was no visible swelling on the right side of the maxilla. Intraoral examination revealed a large sessile lobulated gingival overgrowth extending on buccal surfaces of 15, 16, 17 and 18. It was reddish pink in color with white patches and was approximately 21 mm × 44 mm in size. The surface was smooth no ulcerations were seen and it appeared ovoid in shape [Figure 1]. Buccally it extended beyond the occlusal plane of the teeth giving an appearance of missing teeth [Figure 2]. Oral hygiene was poor and the mouth showed large amounts of calculus. Teeth associated with it did not show any mobility. Radiographically, there were no visible abnormalities and the alveolar bone in the region of the growth appeared normal [Figure 3]. Routine hemogram was found to be normal. A provisional diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma was made. The differential diagnosis included peripheral ossifying fibroma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, hemangioma and fibroma.

Figure 1.

Buccal view of the gingival growth

Figure 2.

Occlusal view of the gingival growth

Figure 3.

Orthopantomogram of the patient

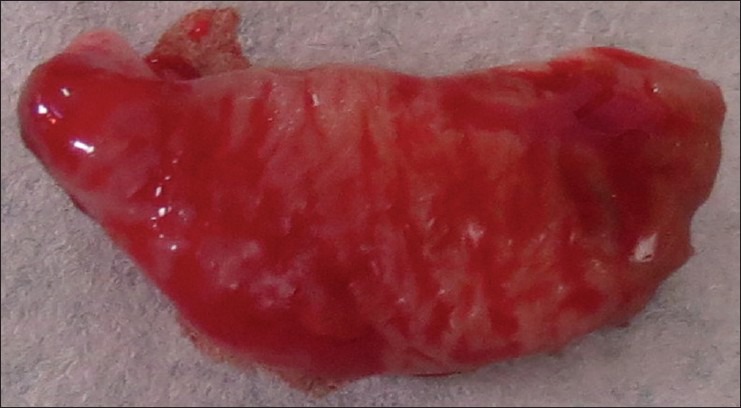

The patient did not have any systemic problems and so the case was prepared for surgery on the basis of the clinical and radiographic evidence. Oral prophylaxis was completed and the lesion was excised under aseptic conditions. Excision of the lesion up to and including the mucoperiosteum was carried out under local anesthesia using a scalpel and blade, followed by curettage and through scaling of the involved teeth. Periodontal dressing was placed and the patient was recalled after 1 week for removal of the pack and checkup. The excised tissue [Figure 4] was sent to the Department of Oral Pathology for histologic examination.

Figure 4.

Excised tissue

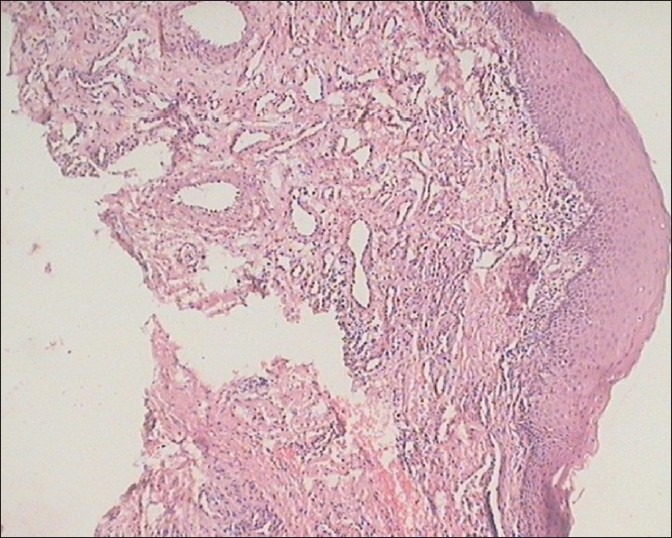

Histopathological report revealed parakeratinized epithelium, stretched in some places and showed proliferation toward the base of the lesion. The underlying connective tissue stroma showed dilated and engorged blood vessels, extravasated red blood cells, angiogenesis, few inflammatory cells and bundles of collagen fibers [Figure 5]. The diagnosis pyogenic granuloma was histologically confirmed.

Figure 5.

Histologic section of the growth

The patient was recalled every 3rd month for maintenance and to check for possible recurrence. This case was followed up for a period of 1 year and there has been no recurrence so far [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

1 year follow-up

DISCUSSION

Etiologic factors

Regezi et al.,[8] suggested that pyogenic granuloma is caused by a known stimulant or injury such as calculus or foreign material within the gingival crevice resulting in exuberant proliferation of connective tissue. Ainamo[13] suggested that routine tooth brushing habits cause repeated trauma to the gingiva resulting in irritation and formation of these lesions. Release of variety of endogenous substances and angiogenic factors caused disturbances in the vascularity of the affected area. Trauma to deciduous teeth,[14] aberrant tooth development,[15] occlusal interferences,[16] immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine[11] and wrong selection of healing cap for implants[17] are some of the other precipitating factors for pyogenic granulomas.

Etiopathogenesis

Oral pyogenic granulomas occur in all age groups, children to older adult, but are more frequently encountered in females in their second decade due to the increased levels of circulating hormones estrogen and progesterone.[18] Hosseini et al.,[19] observed that gingival enlargements increased in pregnancy and atrophied in menopause. Yuan et al.,[20] concluded that the morphogenetic factors were higher in pyogenic granuloma rather than normal gingiva supporting the mechanism of angiogenesis in oral pyogenic granulomas in pregnant females. Due to its frequent occurrence in pregnant females pyogenic granuloma is also called as granuloma gravidarum or pregnancy tumor.[7] Hormonal changes and reaction of plaque bacteria are responsible for pregnancy gingivitis in some pregnant female patients.[21] Jafarzadeh et al.,[22] has reviewed the correlation of oral pyogenic granuloma, pregnancy and the role of oral hormonal contraceptives in detail. However, the effects of female hormones on oral pyogenic granulomas was questioned by Bhaskar and Jacoway[2] since they found lesions both in males and females with no specific sex predilection.

In this case, the patient discussed was a 22-year-old healthy male. From the numerous etiologies enumerated above[8,11,13,14,15,16,17] the probable etiologic factors applicable in this case included the presence of large amounts of calculus due to poor oral hygiene habits,[8] repeated trauma and occlusal interference while eating due to the size and position of the lesion[16] and as described by Ainamo,[13] recurrent trauma occurring during tooth brushing or function with the release of various endogenous and angiogenic factors contributing to the increased vascularity of the lesion. These factors probably contributed to the development of this lesion.

Pagliai and Cohen[23] describing pyogenic granulomas in children used the terminology LCH to described pyogenic granuloma as a benign, acquired, vascular neoplasm of the skin and mucous membrane. Davies et al.,[24] noted that the fibroblasts in pyogenic granulomas showed increased synthetic activity and presence of intranuclear inclusion bodies suggesting that pyogenic granulomas of the skin arise from disordered growth of the papillary dermis.

Bhaskar and Jacoway[2] demonstrated the presence of gram positive and gram negative bacilli in the superficial areas of the ulcerated form of pyogenic granuloma, rather than the non-ulcerated form suggesting that these organisms could be contaminants from the oral cavity. This probably justifies the inclusion of the term “pyogenic” in pyogenic granuloma. Oral pyogenic granuloma show prominent capillary growth within a granulomatous mass rather than the real pyogenic organisms and pus, so the term pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer and it is not a granuloma in the real sense.[7,8]

The lesion in the patient was not ulcerated.

Clinical features

Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity appears as an elevated, smooth or exophytic, sessile or pedunculated growth covered with red hemorrhagic and compressible erythematous papules, which appear lobulated and warty showing ulcerations and covered by yellow fibrinous membrane.[7,8] The color varies from red, reddish purple to pink depending on the vascularity of the growth.[25] The gingiva, especially the marginal gingiva is affected more than the alveolar part.[26] Besides the gingiva it is also noticed on the lips, tongue or buccal mucosa, affecting the maxilla more than the mandible, the anterior region than the posterior with the buccal surfaces being affected more than the lingual surfaces. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters and it is usually slow growing, asymptomatic, painless growth,[7,8] but at times it grows rapidly.[27]

The case presented here showed a large growth localized to the buccal surfaces of the upper right posterior maxilla, reddish pink in color, the growth was present since 2 years it had gradually increased in size, it had started to bleed intermittently and it also interfered during mastication, which prompted the patient to seek treatment. The growth involved the attached gingiva and the marginal gingiva [Figures 1 and 2] extending beyond the occlusal plane, thereby interfering with mastication.

Histopathology

Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are classified as the LCH type and the non-LCH type.[7,22,28] The LCH type has proliferating blood vessels organized in lobular aggregates, no specific changes such as edema, capillary dilation or inflammatory granulation were noted. The non-LCH type consisted of a vascular core resembling granulation tissue with foci of fibrous tissue. The lobular area of the LCH type has a greater number of blood vessels with small luminal diameter than that in a non-LCH type of pyogenic granuloma. In the central area of the non-LCH pyogenic granuloma a greater number of vessels with perivascular mesenchymal cells non-reactive for alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA) is detected as compared with the lobular area of the LCH type pyogenic granuloma, thereby Epivatianos et al., suggested that the LCH and the non-LCH pyogenic granulomas have different pathways of evolution.[29] Sato et al.,[30] described most oral pyogenic granulomas as the LCH type histologically. They investigated the relationship of human endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2 and its expression in the lobular capillary hemorrhage LCH type pyogenic granulomas and that the expression of Tie2 in the ovoid cells with the presence of alpha SMA antibodies played an important role in the development and progression of the LCH type of pyogenic granulomas. Regezi et al.,[8] demonstrated a strong activity of angiogenesis in oral pyogenic granulomas by demonstrating prominent capillary growth in the hyperplastic granulation tissue. Yuan et al.,[20] suggested the etiology of pyogenic granuloma to be due to an imbalance between the angiogenesis enhancers vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and angiogenesis inhibitors angiostatin and thrombospodin1. Vascular morphogenesis factors Tie-2, angiopoietin 2, ephrin B2 and ephrin were found to be up-regulated in oral pyogenic granulomas. Jafarzadeh et al.,[22] emphasized the importance of decorin, VEGF, connective tissue growth factors, bFGF basic fibroblast growth factor on angiogenesis associated with profound inflammation. Sternberg et al.,[12] described the natural course of the lesion in three phases of development as cellular phase, vascular phase and the phase of involution. Bhaskar and Jacoway[2] described pyogenic granuloma as covered with parakeratotic or non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

The biopsy report in this case report shows that the bulk of the lesion shows angiomatous tissue with endothelial cell proliferation, inflammatory cell infiltrate is seen in the form of few neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells covered by parakeratinized epithelium [Figure 5] and confirmed the diagnosis of oral pyogenic granuloma of the LCH type as described.

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings are usually absent.[31] However, Angelopoulos[4] concluded that in some cases long standing gingival pyogenic granulomas caused localized alveolar bone resorption.

In the present case, there were no obvious radiographic findings [Figure 3].

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included peripheral giant cell granuloma, peripheral ossifying fibroma, metastatic cancer,[8] hemangioma,[32] pregnancy tumor,[33] conventional granulation tissue hyperplasia, Kaposi's sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis[34] and non-Hodgkins lymphoma.[35] Peripheral giant cell granuloma can be histologically identified due to the presence of multinucleated giant cells[8] and lack of an infectious source.[31] Ossifying fibroma or peripheral odontogenic fibroma occurs exclusively on the gingiva; however, it has a minimal vascular component unlike a pyogenic granuloma.[8,36] Due to the proliferating blood vessels differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma from a hemangioma is made histologically in which hemangioma shows endothelial cell proliferation without acute inflammatory cell infiltrate,[34] which is a common finding in pyogenic granuloma. Metastic tumors of the oral cavity are rare and attached gingiva is commonly affected, clinically they resemble reactive or hyperplastic lesions such as pyogenic granuloma, but microscopically they usually resemble the tumor of origin, which usually is distant from the metastatic lesion seen in the oral cavity.[22] The diagnosis of pregnancy tumor is based on the history and the apparent influence of the female sex hormones.[37,38] Conventional hyperplastic gingival inflammation resembles pyogenic granuloma in histopathologic sections and it is impossible for the pathologist to reach a diagnosis and in such cases the surgeons description of the lesion is relied on.[39] Pyogenic granuloma is distinguished from Kaposi's sarcoma in Acquired immune deficiency syndrome due to the proliferation of dysplastic spindle cells, vascular clefts, extravasated erythrocytes and intracellular hyaline bodies[39] none of which are seen in pyogenic granuloma.

Treatment

Excision and biopsy of the lesion is the recommended line of treatment unless it would produce a marked deformity and in such a case incisional biopsy is recommended.[36] Conservative surgical excision of the lesion with removal of irritants such as plaque, calculus and foreign materials is recommended for small painless non-bleeding lesions. Excision of the gingival lesions up to the periosteum with through scaling and root planning of adjacent teeth to remove all visible sources of irritation is recommended.[7]

In the present case, the lesion was surgically excised and was sent for histopathologic examination. The scaling and root planning of the adjacent teeth was completed to remove all the local irritants, which could have been the primary etiologic factor in the present case.[8]

Various other treatment modalities such as use of Nd: YAG laser, carbon dioxide laser, flash lamp pulse dye laser, cryosurgery, electrodessication, sodium tetradecyl sulfate sclerotherapy[22] and use of intra lesional steroids[27] have been used by various clinicians.

Treatment of oral pyogenic granulomas during pregnancy would depend on the individual case and ranges from preventive measures such as careful oral hygiene, removal of dental plaque and use of a soft toothbrush.[37] Wang recommended control of bleeding by desiccation of bleeders, firm compression of the lesion, use of blood transfusions in a case of severe bleeding from a pregnancy tumor and in rare cases termination of pregnancy due to uncontrollable eclampsia have been documented.[40] In some cases shrinkage of the lesion after pregnancy may make surgical treatment unnecessary.[39] In pregnant females recurrence of oral pyogenic granulomas is common so treatment should be preferably performed after parturition.[32] However, if necessary treatment can be completed in the second trimester with follow-up of the case post-parturition.[37]

Recurrence

Taira et al.,[36] have shown a recurrence rate of 16% in excised lesions and also described a case of multiple deep satellite lesions surrounding the original excised lesion in a case of Warner Wilson James syndrome. Incomplete excision, failure to remove etiologic factors or repeated trauma contributes to recurrence of these lesions.[8] Vilmann et al.,[26] emphasized the need of follow-up, especially in pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva due to its much higher recurrence rate.

The present case was followed up for a period of 1 year and no recurrence was observed.

CONCLUSION

Pyogenic granuloma is a common lesion of the skin and oral cavity, especially the gingiva. This case report presents a case of a large gingival pyogenic granuloma in a male patient giving an insight into its myriad etiologies, clinical features, histological presentations, treatment modalities and recurrence rates and describes how the diagnosis and treatment of one such case was completed and followed up for a period of 1 year. The article also highlights that though the term pyogenic granuloma is frequently used it is not associated with pus and histologcally it resembles angiomatous lesion rather than granulomatous lesion indicating that the term “pyogenic granuloma” is a misnomer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank Prof. Sandhya Tamgadge, Department of Oral Pathology, Pad. Dr. D. Y. Patil Dental College, Nerul for her help and guidance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hullihen SP. Case of aneurism by anastomosis of the superior maxillae. Am J Dent Sci. 1844;4:160–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhaskar SN, Jacoway JR. Pyogenic granuloma – Clinical features, incidence, histology, and result of treatment: Report of 242 cases. J Oral Surg. 1966;24:391–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartzell MB. Granuloma pyogenicum. J Cutan Dis Syph. 1904;22:520–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angelopoulos AP. Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity: Statistical analysis of its clinical features. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:840–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cawson RA, Binnie WH, Speight PM, Barrett AW, Wright JM. 5th ed. Missouri: Mosby; 1998. Lucas Pathology of Tumors of Oral Tissues; pp. 252–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao T, Nagai E, Utsunomiya T, Tsuneyoshi M. An intestinal counterpart of pyogenic granuloma of the skin. A newly proposed entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1054–60. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; pp. 447–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RC. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2003. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathological Considerations; pp. 115–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mussalli NG, Hopps RM, Johnson NW. Oral pyogenic granuloma as a complication of pregnancy and the use of hormonal contraceptives. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1976;14:187–91. doi: 10.1002/j.1879-3479.1976.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janier M. Infection and angiomatous cutaneous lesions. J Mal Vasc. 1999;24:135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmeyer C, Devergie A, Mansouri S, Dubertret L, Aractingi S. Pyogenic granuloma of the tongue in chronic graft versus host disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:552–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sternberg SS, Antonioli DA, Carter D, Mills SE, Oberman H. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams and Wilkins; 1999. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology; pp. 169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainamo J. The effect of habitual toothcleansing on the occurrence of periodontal disease and dental caries. Suom Hammaslaak Toim. 1971;67:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilo L. Pyogenic granuloma subsequent to injury of a primary tooth. A case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:438–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2000.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milano M, Flaitz CM, Bennett J. Pyogenic granuloma associated with aberrant tooth development. Tex Dent J. 2001;118:166–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widowati W, Ban T, Shareff A. Epulis and pyogenic granuloma with occlusal interference. Maj Ked Gigi. 2005;38:52–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dojcinovic I, Richter M, Lombardi T. Occurrence of a pyogenic granuloma in relation to a dental implant. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1874–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojanotko-Harri AO, Harri MP, Hurttia HM, Sewón LA. Altered tissue metabolism of progesterone in pregnancy gingivitis and granuloma. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:262–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosseini FH, Tirgari F, Shaigan S. Immunohistochemical analysis of estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in gingival lesions. Iran J Public Health. 2006;35:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. Expression of Tie-2, angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, ephrinB2 and EphB4 in pyogenic granuloma of human gingiva implicates their roles in inflammatory angiogenesis. J Periodontal Res. 2000;35:165–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035003165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sooriyamoorthy M, Gower DB. Hormonal influences on gingival tissue: Relationship to periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:201–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: A review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167–75. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagliai KA, Cohen BA. Pyogenic granuloma in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:10–3. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies MG, Barton SP, Atai F, Marks R. The abnormal dermis in pyogenic granuloma. Histochemical and ultrastructural observations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:132–42. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(80)80392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mubeen K, Vijaylakshmi KR, Abhishek RP. Oral pyogenic granuloma with mandible involvement: An unusual presentation. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2011;3:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilmann A, Vilmann P, Vilmann H. Pyogenic granuloma: Evaluation of oral conditions. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:376–82. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parisi E, Glick PH, Glick M. Recurrent intraoral pyogenic granuloma with satellitosis treated with corticosteroids. Oral Dis. 2006;12:70–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills SE, Cooper PH, Fechner RE. Lobular capillary hemangioma: The underlying lesion of pyogenic granuloma. A study of 73 cases from the oral and nasal mucous membranes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:470–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epivatianos A, Antoniades D, Zaraboukas T, Zairi E, Poulopoulos A, Kiziridou A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity: Comparative study of its clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Pathol Int. 2005;55:391–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato H, Takeda Y, Satoh M. Expression of the endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2 in lobular capillary hemangioma of the oral mucosa: An immunohistochemical study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:432–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.310708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamal R, Dahiya P, Puri A. Oral pyogenic granuloma: Various concepts of etiopathogenesis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:79–82. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.92978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eversole LR. 3rd ed. Hamilton: BC Decker; 2002. Clinical Outline of Oral Pathology: Diagnosis and Treatment; pp. 113–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tumini V, Di Placido G, D’Archivio D, Del Giglio Matarazzo A. Hyperplastic gingival lesions in pregnancy. I. Epidemiology, pathology and clinical aspects. Minerva Stomatol. 1998;47:159–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calonje E, Wilson-Jones E. Vascular tumors: Tumors and tumor like conditions of blood vessels and lymphatics. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, Johnson B Jr, editors. Lever's Histopatology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadephia: Lippicott-Raven; 1997. p. 895. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raut A, Huryn J, Pollack A, Zlotolow I. Unusual gingival presentation of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder: A case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:436–41. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.107446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taira JW, Hill TL, Everett MA. Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) with satellitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70184-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: Case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daley TD, Nartey NO, Wysocki GP. Pregnancy tumor: An analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:196–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouquot JE, Nikai H. Lesions of the oral cavity. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of Head and Neck. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001. pp. 141–233. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang PH, Chao HT, Lee WL, Yuan CC, Ng HT. Severe bleeding from a pregnancy tumor. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]