Abstract

The naive T-cell pool in peripheral lymphoid tissues is fairly stable in terms of number, diversity and functional capabilities in spite of the absence of prominent stimuli. This stability is attributed to continuous tuning of the composition of the T-cell pool by various homeostatic signals. Despite extensive research into the link between signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) and T-cell survival, little is known about how Stat3 regulates homeostasis by maintaining the required naive T-cell population in peripheral lymphoid organs. We assessed whether the elimination of Stat3 in T cells limits T-cell survival. We demonstrated that the proportion and number of single-positive thymocytes as well as T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes were significantly decreased in the Stat3-deficient group as a result of the enhanced susceptibility of Stat3-deleted T lymphocytes to apoptosis. Importantly, expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL was markedly decreased in Stat3-deleted single-positive thymocytes and T lymphocytes, suggesting that Stat3 helps to maintain the T-cell pool in the resting condition by promoting the expression of Bcl-2 family genes. These findings suggest the importance of Stat3 in the integration of homeostatic cues for the maintenance and functional tuning of the T-cell pool.

Keywords: apoptosis, Bcl-2, homeostasis, Stat3, T cell

Introduction

Following development and education in the thymus, mature naive T cells are maintained in peripheral lymphoid organs including the spleen and lymph nodes.1,2 In spite of constant output from the thymus, the number of peripheral naive T cells is fairly constant, which implies a balance between the death and replacement of peripheral naive T cells. The peripheral naive T-cell pool is relatively unchanged in number in the absence of noticeable inflammatory responses.3 This stability is not, however, an intrinsic characteristic of T cells, but requires adjustment of the T-cell pool balance by various homeostatic signals. Naive T cells survive for several weeks in the absence of prominent antigen stimulation, and withdrawal or activation of homeostatic signals can control this lifespan.2 Numerous studies have shown that the homeostasis of naive T cells is supported by the combination of self-peptide MHC complexes and interleukin (IL-7) signals.4,5

A pivotal feature of these homeostatic cues and the downstream signals is the enhancement of T-cell survival by regulation of the expression of pro-survival B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family proteins.6 Regulated cell loss is crucial for proper differentiation and for the maintenance of homeostasis in T cells. Bcl-2 is an essential molecule that determines the susceptibility to apoptosis in various lineages.7 Previous studies have shown that constitutive expression of Bcl-2 in lymphoid cells inhibits or delays apoptosis induced by multiple stimuli.8

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3), as a key regulator of Bcl-2 family genes, plays a role in promoting the expression of pro-survival oncogenic factors during tumorigenesis.9 Stat3 has indispensable functions in differentiation, cell growth and the regulation of cell death in various tissues.10 Diverse Stat3 targets contribute to T-cell pathogenesis and homeostasis. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and massive parallel sequencing showed that Stat3 bound to the promoters of multiple genes involved in T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, T-cell activation, proliferation and survival.11 Moreover, targeted deletion of Stat3 in CD4+ T cells prevented autoimmune disease development.12 Patients with Job's or Hyper IgE Syndrome have dominant-negative mutations of Stat3 and are relatively deficient in Th17 cells, implying a close link between Stat3 and Th17 cells.13 Furthermore, IL-6 trans-signalling via Stat3 directed T-cell infiltration in acute inflammation.14 The IL-6/Stat3 signalling also regulated the ability of naive T cells to become B-cell helpers by promoting follicular helper T-cell development.15

In addition to its role in T-cell development and differentiation, several studies have demonstrated that Stat3 promotes the proliferation of activated T cells and regulates the lifespan of T lymphocytes. T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice displayed impaired IL-6-induced and IL-2-induced T-cell proliferation.16,17 Also, Stat3 plays a crucial role in promoting T-cell survival in response to various stimuli.18 Furthermore, Johnston et al.19 suggested that the T-cell growth factors IL-2, IL-7 and IL-15 all activate Stat3 and Stat5. Therefore, transcription complexes that include Stat3 and Stat5 may be of general importance to promote cell proliferation in T cells. Also, Durant et al.11 examined the CD4+ T cells in the spleen and found that the majority of control (Stat3fl/fl) T cells underwent multiple cell divisions after 5 days. In contrast, fewer than half of Stat3−/− T cells had divided, as indicated by CFSE dilution. By 7 days, essentially all of the control T cells had divided, whereas 18% of Stat3−/− T cells remained quiescent.

In spite of current knowledge about the link between Stat3 and T-cell survival, little is known about how Stat3 regulates T-cell homeostasis in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Using mice with targeted deletion of Stat3 in T cells, we showed that Stat3 maintains the CD4 or CD8 single-positive (SP) thymocytes and naive T-cell pool in the resting condition by promoting the expression of Bcl-2 family genes. This discovery magnifies the significance of Stat3 as a master regulator of homeostatic signals for the maintenance and functional adjustment of the naive T-cell population.

Materials and methods

Generation of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice

Mice homozygous for the loxP-flanked (floxed) Stat3 gene (Stat3fl/fl) were a kind gift from Dr S. Akira. Mice carrying a Cre transgene under the control of the distal Lck promoter (Lck-CRE+/+)were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice with a Stat3 deletion in T cells were generated by crossing mice with the floxed Stat3 allele with mice expressing Cre under the control of the Lck promoter.17 Genomic DNA was isolated from tail tips using a NucleoSpin genomic DNA purification kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co., Duren, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). Genotyping was performed with the primers CCTGAAGACCAAGTTCATCTGTGTGAC and CACACAAGCCATCAAACTCTGGTCTCC, which are specific for exons 22 and 23 of Stat3, respectively.20 Mice carrying Cre were identified by genotyping with the primers GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC and GTGAAACAGATT-GCTGTCACTT, which are specific for the Cre transgene, according to the manufacturer's instructions. All animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and all experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the College of Medicine, Seoul National University.

Flow cytometry and cell death analyses

Single-cell suspensions from thymocytes, splenocytes or mesenteric lymph node cells were stained with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 antibody, an FITC-labelled antibody against CD8, allophycocyanin-labelled anti-CD3, anti-Foxp3, Alexa647-conjugated CD62L, and/or FITC-labelled CD44 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Splenocytes were fixed and permeabilized using the FoxP3 staining buffer set (eBioscience, Inc., San Diego, CA), and were then incubated with anti-Bcl-2 or anti-Bcl-xL (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Cells that had undergone apoptosis were detected by flow cytometry using an FITC-annexin V antibody and annexin V staining solution (BioLegend), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry analyses were performed using a FACS Canto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The data were analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

In vivo bromodeoxyuridine incorporation assay

The proliferation rate of T lymphocytes in control and Stat3-deficient mice was measured by in vivo bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay, as described previously.21 Briefly, 2 mg BrdU solution (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) in PBS was injected intraperitoneally into control (Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE−/−) and Stat3-deficient (Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/−) mice. Twelve hours after injection, splenocytes were isolated from both groups of mice. Purified splenocytes were stained with the allophycocyanin-anti-mouse CD3 antibody (BioLegend). Next, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using a FoxP3 intracellular staining kit (eBioscience), and then labelled with an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody using a BrdU Flow Kit (BD Pharmingen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry analyses were conducted on a FACSCanto flow cytometer. The data were analysed using FlowJo software.

Purification of splenic T cells

Splenic T cells were enriched using a Pan T-cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech Inc., Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, non-T cells in a cell suspension from the spleen were magnetically labelled. Then, non-T cells were removed by magnetic selection with an autoMACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotech Inc.). Isolated splenic T-cell purity was over 97% (data not shown).

Immunoblotting

Isolated thymocytes or splenic cells were harvested in a lysis solution (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and a phosphatase inhibitor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Total protein samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). The membranes were then probed with antibodies against Stat3, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, cleaved caspase-3, or β-actin (Cell Signalling Technology) and visualized using SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA).

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assays

Total RNA was purified from isolated spleen cells using the RNeasy Plus kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and cDNA was synthesized using a QuantiTech Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Then, cDNA was mixed with QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR master mix (Qiagen) and specific primers. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed with an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Raw data were analysed by comparative Ct quantification.22 Primers specific for human Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were obtained from Qiagen.

Immunofluorescence and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay

To perform immunofluorescence analyses, spleens or thymuses were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and sectioned to a thickness of 10 μm using a cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Sections were incubated overnight at 4° with an anti-CD3-biotin (BD Pharmingen) plus anti-Bcl-2 or anti-Bcl-xL (Cell Signaling Technology), and then incubated with appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. TUNEL assays were conducted using the TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (GeneScript, Piscataway, NJ), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Stained sections were mounted in VectaShield 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and were analysed under an LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Two-tailed Student's t-tests were conducted using the GraphPad Prism software (ver. 5.01; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

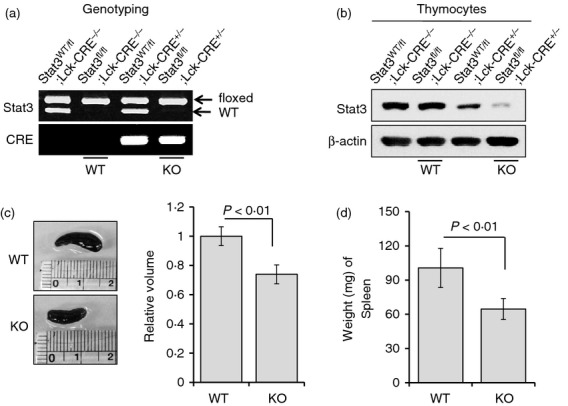

Generation of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice

Mice homozygous for Stat3fl/fl were mated with mice carrying the Cre transgene under the control of the Lck promoter. The first offspring generation (F1) carrying the Lck transgene and heterozygous for the floxed Stat3 gene (Stat3WT/fl Lck-CRE+/−) was further mated with Stat3fl/fl mice. The second offspring generation (F2) had four distinct genotypes: Stat3WT/f lLck-CRE+/−, Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE−/−, Stat3WT/fl Lck-CRE+/− and Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1). Genotyping using primers specific for exons 22 and 23 of Stat3 allowed identification of mice carrying the floxed Stat3 allele by bands of ∼ 350 bp in an agarose gel, whereas mice with wild-type Stat3 alleles showed bands ∼ 50 bp smaller than those with floxed alleles. Accordingly, we discriminated mice that were homozygous for the floxed Stat3 allele (Stat3fl/fl) from mice carrying both wild-type and floxed Stat3 alleles (Stat3WT/fl). Mice with the Cre transgene under the control of the Lck promoter were identified using primers specific for Cre transgene sequences (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Generation and identification of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. (a) Stat3fl/fl mice were identified by a single band at ∼ 350 bp on an agarose gel, while Stat3WT/fl mice showed another band ∼ 50 bp smaller than the floxed allele, which represents the wild-type Stat3 allele. Genotyping was performed using primers specific for exons 22 and 23 of Stat3. Lck-CRE+/− mice were identified by a single band at ∼ 100 bp on an agarose gel using primers specific for the Cre transgene. (b) Stat3 expression in thymocytes from each group of mice was determined (identified by genotyping) by immunoblotting. Stat3WT/fl Lck-CRE−/− and Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE−/− mice showed relatively high Stat3 protein levels, while Stat3WT/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice demonstrated reduced Stat3 expression, and Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice exhibited the lowest Stat3 expression. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (c) The volumes of spleens from each group of mice were measured at 8 weeks using vernier callipers. The volume of the spleen was about 20% smaller in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice compared with control mice. (d) The weights of spleens from each group of mice were measured at 8 weeks. Spleen weight was about 35% lower in the Stat3-deficient group compared with controls. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test.

The Stat3 protein level in thymocytes was measured by immunoblotting. As expected, mice without a Cre transgene in the Lck promoter showed high expression of Stat3 protein, independent of the floxed Stat3 allele, whereas mice carrying Cre transgenes demonstrated reduced expression of Stat3, which was dependent on the level of floxed Stat3 allele (Fig. 1b). Based on our data, we assigned Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE−/− mice as the control group and Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice as the test group; i.e. mice with Stat3-deficient T cells.

The volume of the spleen was about 20% lower in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice compared with the control group (Fig. 1c). Also, the weight of the spleen was ∼ 35% lower in Stat3-deficient mice compared with control mice (Fig. 1d).

T-cell-specific Stat3 deletion resulted in T-cell deficiency in the spleen and lymph nodes

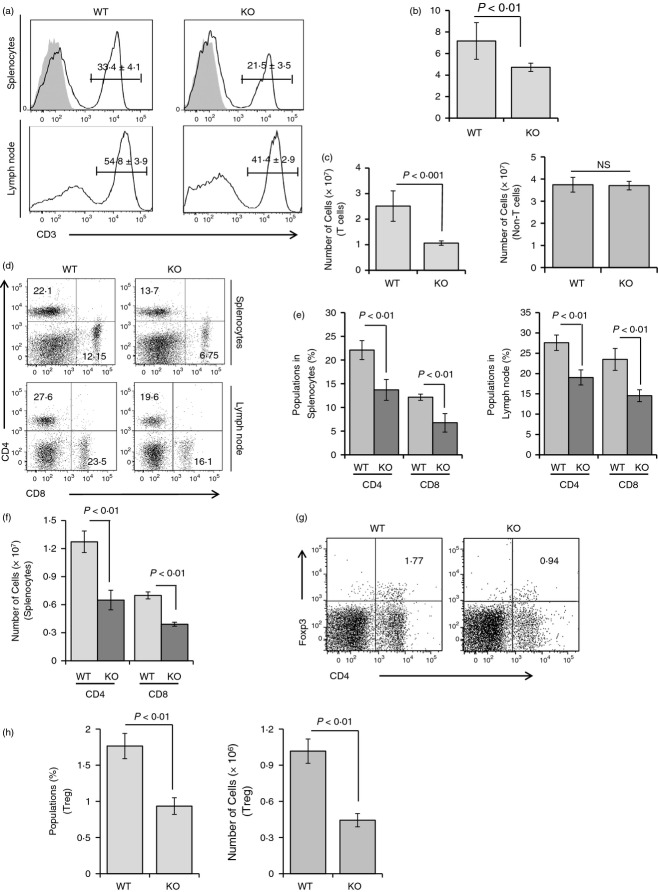

To determine whether the reductions in splenic volume and weight in the Stat3-deficient group were attributable to a deficiency in the T-cell population, FACS analysis was performed. The population of CD3-positive T cells in the spleen or mesenteric lymph node was reduced by ∼ 35–45% in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Depletion of T lymphocytes in the spleens and lymph node cells of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. (a) Splenocytes or lymph node cells were isolated from each group of mice at 8 weeks and stained with allophycocyanin (APC) -conjugated anti-mouse CD3 antibody. The population of CD3-positive T cells was decreased by ∼ 35–45% in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. Filled grey traces: isotype controls. (b) Absolute numbers of total splenocytes from each group of mice at 8 weeks were counted using a haemocytometer. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test. (c) Numbers of T cells and non-T cells among splenocytes were estimated from flow cytometry data. Total numbers of splenocytes were decreased by ∼ 30% in Stat3-deficient mice. The estimated number of T cells was reduced by about ∼ 45–50% in Stat3-deficient mice whereas numbers of non-T cells were comparable in both groups. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test. (d) FACS analyses of splenocytes or lymph node cells from both groups of mice were performed to identify the differences between CD4-positive and CD8-positive populations. Cells were isolated from each group of mice at 8 weeks and stained with phycoerythrin (PE) -conjugated anti-mouse CD4 and FITC-labelled CD8 antibody. FACS data were representative of three independent experiments, six mice per group. (e) Percentage of CD4-positive or CD8-positive cells in splenocytes (left) or lymph node cells (right) was analysed and demonstrated as bar graphs. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test. (f) Absolute cell number of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in splenocytes from control or Stat3-deficient mice were displayed. The cell numbers were calculated from the FACS data in (e) and the total cell number of splenocytes. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test. (g) The CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell population was analysed on splenocytes from control or Stat3-deficient mice. Splenocytes were isolated from each group of mice at 8 weeks and were fixed/permeabilized using Foxp3-staining buffer (eBioscience, Inc.). Cells were probed with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 and APC-labelled anti-Foxp3 antibody (BioLegend). FACS data were representative of three independent experiments, six mice per group. (h) The percentage (left) or the cell numbers (right) of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells in splenocytes was analysed and demonstrated as bar graphs. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test.

Absolute total splenocyte numbers were counted using a haemocytometer, and T-cell and non-T-cell numbers were calculated according to flow cytometry results. The total number of splenocytes was significantly reduced in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice (Fig. 2b). The number of CD3-positive T cells was reduced to a greater degree than that of splenocytes in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice; non-T-cell numbers in the spleen were similar in both groups (Fig. 2c). This implies that the reduced volume, weight and cell number in spleens of T-cell-specific Stat3-deleted mice was a result of the T-cell deficiency.

Because it has been reported that Lck-driven Cre expression is toxic for developing T cells,23 we also compared the splenic volumes, the proportion and the absolute number of T cells in spleens from Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE−/− and Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE+/− to exclude the possibility that our results were attributable to the off-target effect of Cre-recombinase to developing T cells. Both the volume of spleens and the absolute number of T cells showed only minimal decrease in Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE+/− mice compared with Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE−/− mice at 8 weeks (see Supplementary material, Fig. S2a–c), while the significant T-cell depletion was observed in spleens from Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice compared with those from Stat3WT/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice (Fig. S2d,e). Furthermore, we analysed the subpopulation of thymocytes in Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE−/− and Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE+/− mice (Fig. S2f–h). Both the population and the absolute number of double-positive, CD4 and CD8 SP cells were unvarying between CRE−/− and CRE+/− mice at 6 months (Fig. S2f–h). These results indicate that the T-cell deficiency in Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice largely resulted from Stat3 deletion, rather than from the off-target toxicity of Cre-recombinase.

We next investigated the proportion of CD4- or CD8-positive T cells in spleen and lymph node. Both the CD4 and CD8 populations were considerably decreased in the Stat3-deleted group (Fig. 2d–f). Also, the population and the absolute number of CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells, which are regarded as regulatory T cells, were notably decreased in spleens from Stat3-deficient mice when compared with the control group (Fig. 2g,h).

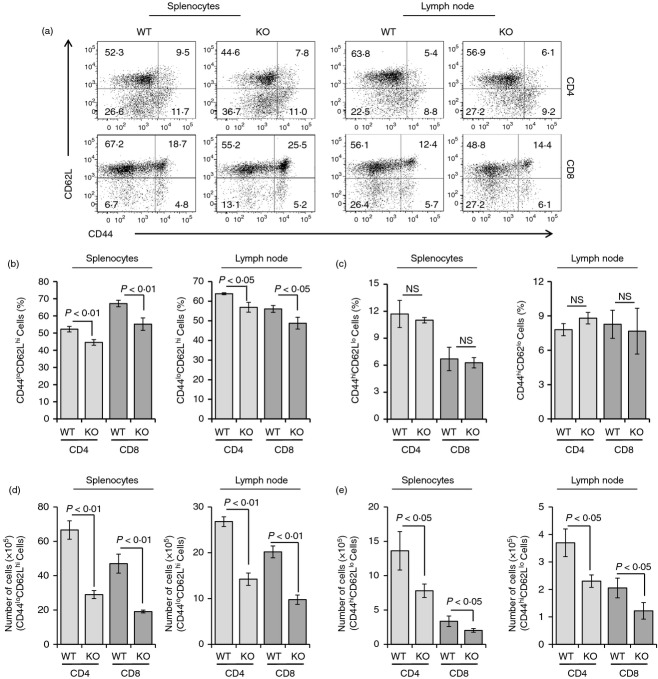

Population of both naive and effector/memory T cells was decreased in T cell-targeted Stat3-deleted mice

To observe the variation of naive or effector/memory T-cell population in peripheral T cells from wild type or Stat3 knockout mice, we performed flow cytometry analyses with CD4, CD8, CD62L and CD44 staining (Fig. 3). The CD62Lhigh and CD44low population in both CD4- and CD8-positive T lymphocytes, which has been identified as naive T cells, was considerably reduced in splenocytes and lymph node cells from the Stat3-deficient group (Fig. 3a,b), whereas the population of CD62Llow and CD44high effecteor/memory T cells was unvarying in both groups (Fig. 3a,c). However, the absolute cell numbers were reduced in both naive and memory/effector T lymphocytes from control and Stat3 knockout cells (Fig. 3d,e). These data suggest that Stat3 plays crucial roles in the maintenance of not only naive but also memory/effector T cells.

Figure 3.

Reductions in naive T lymphocytes in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. (a) Splenocytes or mesenteric lymph node cells were isolated from each group of mice at 8 weeks and stained with fluorescence-labelled CD4, CD8, CD62L and CD44 antibody. FACS data were representative of three independent experiments, six mice per group. (b) Percentage of CD44low CD62Lhigh cells in CD4-positive or CD8-positive T cells from splenocytes (left) or lymph node cells (right) was analysed and demonstrated as bar graphs. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test. (c) CD44high CD62Llow cell population in CD4-positive or CD8-positive T cells from spleens (left) or mesenteric lymph node cells (right) was examined and displayed as bar graphs. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test. The absolute cell numbers of CD44low CD62Lhigh cells (d) or CD44low CD62Lhigh cells (e) in CD4-positive or CD8-positive T cells from splenocytes or lymph node cells were analysed and demonstrated as bar graphs. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test.

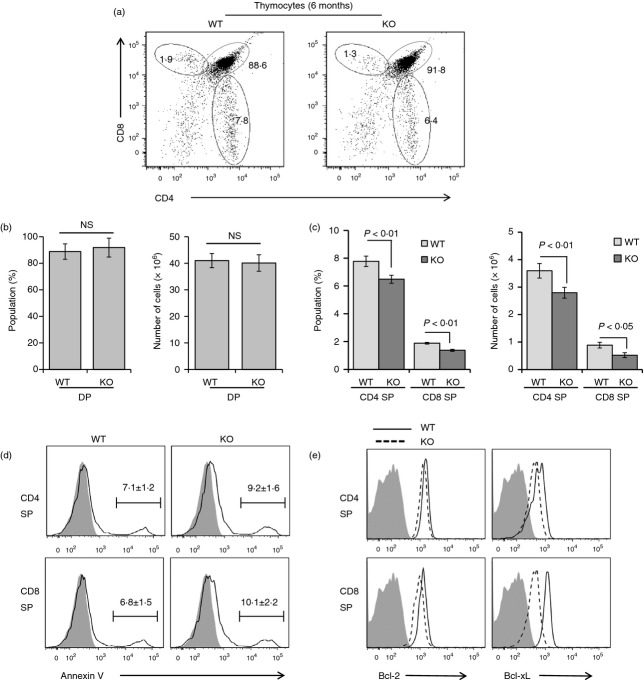

Stat3 maintains the population of CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes by promoting Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression

Both the per cent population and the absolute cell numbers of the CD4 or CD8 SP population in thymocytes was significantly reduced in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice at the age of 6 months, whereas those of CD4+ CD8+ double-positive cells were unvarying between both groups (Fig. 4a–c). However, the populations of double-positive, CD4 SP and CD8 SP showed negligible differences between control and Stat3 knockout mice at 4 or 8 weeks of age (data not shown). Next, we investigated whether the decrease of SP cells resulted from the enhanced susceptibility to apoptosis. The annexin V-positive population in CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes was ∼ 45% higher in Stat3-deficient mice compared with control mice (Fig. 4d). We further examined the expression level of pro-survival Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in SP thymocytes by flow cytometry analyses. Both Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression were significantly decreased in both CD4 and CD8 SP thymocytes from Stat3-deficient cells compared with the control mice (Fig. 4e). The expression of Bcl-2 family genes may be important for the survival of CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes. These results collectively imply that Stat3 contributes the maintenance of SP thymocytes by promoting the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL genes.

Figure 4.

Analysis of subpopulation from thymocytes. (a) Thymocytes were isolated from each group of mice at 6 months and stained with phycoerythrin (PE) -conjugated anti-mouse CD4 and FITC-labelled anti-mouse CD8 antibodies. The population of both CD4 and CD8 single-positive cells were significantly decreased in T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. Data are represented in three independent experiments, n = 6 per group. Both the percentage (left) and the absolute number (right) of CD4/CD8 double-positive cells (b) or CD4/CD8 single-positive cells (c) from each group of mice were analysed and displayed as a bar graph. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations of values from six mice per group. P-values were obtained using the two-tailed Student's t-test. (d) Thymocytes isolated from each group of mice at 6 months were probed with PE-anti-mouse CD4, allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-mouse CD8 and FITC-anti-annexin V antibodies in annexin V binding buffer, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Proportions of Annexin V-positive cells in the CD4 or CD8 single-positive population are demonstrated as histograms. Data are represented in three independent experiments. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. Filled grey traces: isotype controls. (e) Thymocytes isolated from each group of mice at 6 months were incubated with FITC-anti-mouse CD4 and APC-anti-mouse CD8. Then, cells were fixed and permeabilized with FoxP3+ staining kit (eBioscience) and stained with anti-Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL antibody, followed by appropriate PE-conjugated secondary antibody. Proportion of Bcl-2-positive or Bcl-xL-positive cells in the CD4 or CD8 single-positive population are presented as histograms. Data are represented in three independent experiments, n = 6 per group. Filled grey traces, lines and dotted lines indicate isotype controls, Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE−/− mice (WT) and Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice (KO), respectively.

To identify the role of Stat3 in thymic selection, we performed flow cytometry analyses of various T-cell receptor vβ chain in thymocytes or splenocytes. The population of T-cell receptor vβ4, 5, 6, 11 or 13 expressing cells in CD4 or CD8 SP cells in thymus was unvarying in Stat3 knockout mice compared with wild-type littermates (see Supplementary material, Fig. S3a,b), which was also observed in splenic T cells (Fig. S3a,c).

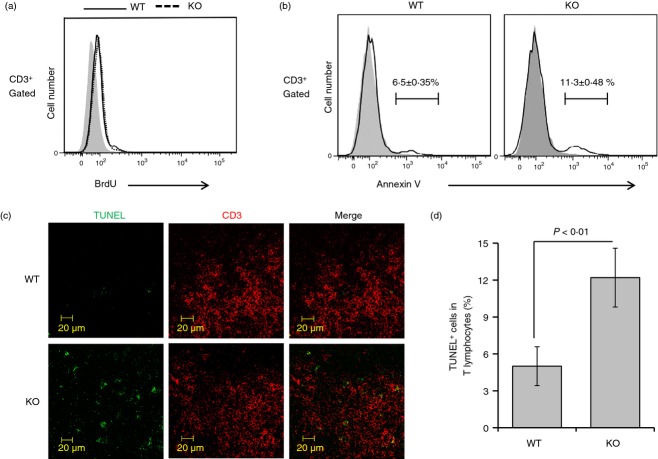

Stat3 deficiency induced apoptosis in T cells

To determine whether the deficiency in T cells in Stat3-deficient mice was attributable to an altered proliferation rate in T lymphocytes, we conducted in vivo BrdU incorporation assays. The proportion of BrdU-stained cells in CD3-positive populations was similar in Stat3-deficient mice and control mice (Fig. 5a). We next performed annexin V analysis and TUNEL assays to determine whether the T-cell deficiency in Stat3-deficient mice was a result of apoptosis. The annexin V-positive population in splenic T cells was ∼ 75% higher in Stat3-deficient mice compared with control mice (Fig. 5b). In addition, numbers of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells among splenic T cells were considerably increased in Stat3-deficient mice (Fig. 5c,d). These data suggest that Stat3 plays a pivotal role in preventing apoptosis in T lymphocytes.

Figure 5.

Increased apoptosis in Stat3-deficient T lymphocytes. (a) In vivo bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assays were performed to measure the proliferation rate of splenic T lymphocytes. Briefly, 2 mg BrdU was injected intraperitoneally. Twelve hours later, splenocytes were isolated and probed with anti-CD3 and anti-BrdU antibodies (BrdU Flow Kit; BD Pharmingen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The proportions of control and Stat3-deficient cells undergoing proliferation were similar. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Filled grey traces: isotype controls. (b) Splenocytes isolated from each group of mice at 8 weeks were incubated with allophycocyanin-anti-mouse CD3 and FITC-anti-annexin V antibodies in annexin V binding buffer, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Proportions of Annexin V-positive cells in the CD3-gated population are presented as histograms. The annexin V-positive subpopulation of splenic T cells was increased by ∼ 75% in Stat3-deficient mice compared with control mice. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. Filled grey traces: isotype controls. (c) Spleens from each group of mice were isolated and frozen sections were prepared using a cryostat. TUNEL assays were performed using a TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit. The proportion of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells among the CD3-positive population was increased in spleens from Stat3-deficient compared with control mice. (d) Representative data of the results shown in (c). Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using a two-tailed Student's t-test.

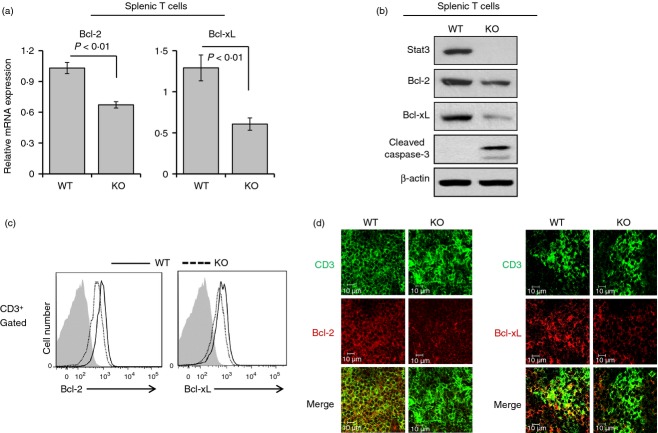

Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression was decreased in T lymphocytes from Stat3-deficient mice

Next, we measured the mRNA expression of Bcl-2 family genes in splenic T cells isolated using the Pan T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech Inc.). Expression of the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL was markedly decreased in the T-cell-specific Stat3-deleted group compared with the control group (Fig. 6a). Stat3, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL protein levels were reduced; accordingly, the expression of cleaved caspase-3 was enhanced in purified T cells from T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, expression of both Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in splenic T cells was considerably reduced in Stat3-deficient mice, as shown by flow cytometry analyses and immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 6c,d). These data collectively suggest that Stat3 plays a crucial role in maintenance of the T-cell population by inducing Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression.

Figure 6.

Suppression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression in Stat3-deficient T cells. (a) Splenic T cells were purified using the Pan T Cell Isolation Kit and an autoMACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotech Inc.). Total RNA was purified and cDNA was synthesized. Quantitiative RT-PCR was conducted and the raw data were analysed by comparative Ct quantification. The mRNA expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL was significantly reduced. Data are presented as means ± SD of six mice per group. P-values were obtained using the two-tailed Student's t-test. (b) Purified splenic T cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Stat3, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL protein levels were reduced in Stat3-deficient T cells. Accordingly, caspase-3 cleavage was considerably increased in Stat3-deficient T cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (c) Flow cytometry analyses of isolated splenocytes demonstrated that the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL was significantly decreased in Stat3-deficient T cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Filled grey traces, lines and dotted lines indicate isotype controls, Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE−/− mice (WT) and Stat3fl/fl Lck-CRE+/− mice (KO), respectively. (d) Spleens were frozen and sectioned. The sections were incubated with anti-CD3-biotin plus anti-Bcl-2 or anti-Bcl-xL, and then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies. Expression of both Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in splenic T cells was markedly attenuated in Stat3-deficient mice. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

We demonstrated that Stat3 contributes to T-cell homeostasis by inducing the expression of Bcl-2 family genes. Stat3 deficiency may enhance the susceptibility of T cells to apoptosis by attenuating the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, resulting in the breakdown of T-cell homeostasis in lymphoid organs.

In the present study, we successfully generated T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice, as described previously17 (Fig. 1). These mice were born healthy and presented no obvious abnormalities. The study in which T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice were first generated showed that these mice had no abnormalities in T-cell development.17 Instead, it demonstrated that Stat3-deficient T lymphocytes have impaired proliferation in response to IL-6 treatment and defective IL-2-mediated IL-2 receptor α chain expression.16,17 However, a recent study reported that the spleen and lymph nodes of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice were smaller than those of wild-type littermates.18 We also found that the spleens of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice were considerably smaller and that their cell numbers were reduced (Figs 1c,d, and 2b). These findings were attributable to the deficiency of T lymphocytes, rather than non-T cells, in Stat3-knockout mice (Fig. 2a,c).

We demonstrated that both the per cent population and absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were reduced in Stat3-deficient mice (Fig. 2d–f). The maintenance of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells has also been reported to be attributable to the common γ chain cytokine signalling in which Stat3 and Stat5 are involved.24,25 Consistently, the population and the number of cells of CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells were notably decreased in Stat3-deficient mice when compared with the control group (Fig. 2g,h). Next, we investigated whether the reduction of CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes was mainly a result of the decrease of naive or memory/effector T cells. The population of CD44low CD62Lhigh naive cells in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes was significantly reduced in splenocytes and lymph node cells from Stat3-deficient mice, whereas that of CD44high CD62Llow effector/memory cells was unchanged (Fig. 3a–c). However, we found that the absolute numbers of both the naive and memory/effector T cells were significantly reduced in Stat3-deficient cells when compared with the control group (Fig. 3d,e). We also observed that the extent of the reduction of naive T cells from Stat3-deficient mice was larger than that of memory/effector T cells when compared with the control group (Fig. 3d,e).

It is accepted that the homeostasis of naive T cells is maintained by the combination of self-peptide MHC complexes and IL-7 signals.4,5 Also, IL-2 plays crucial roles in the differentiation of naive T cells into memory T lymphocytes.26 Moreover, both IL-2 and IL-7 activate Stat3 in T cells.19

Hence, we suggest that Stat3 supports the maintenance and expansion of the naive T-cell pool through the IL-7 receptor signals, as well as mediating memory/effector T-cell production via IL-2-induced signal transduction. Consistently, we showed that both the naive and memory/effector T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs were significantly deficient in Stat3 knockout mice.

Because the mice contain a Cre transgene driven by the distal promoter of Lck gene, Cre-recombinase expression is mainly observed in T cells after T-cell receptor α (Tcra) locus rearrangement and after the process of positive selection in thymic cortex.27 To identify whether the T-cell deficiency in Stat3 knockout mice was attributable to the dysregulation of thymic development, we would have to observe the CD4 and/or CD8 expression pattern in thymocytes from wild-type or Stat3 knockout mice (Fig. 4a). CD4 or CD8 SP cells were unvarying in both groups of mice at 4–8 weeks old (data not shown). However, we observed considerable decreases of both CD4 and CD8 SP cells in thymocytes from Stat3-deficient mice at 6 months old (Fig. 4a,b). A possible mechanism for this finding is that the failure to compensate the Stat3 deficiency occurred on the maintenance of the CD4 or CD8 SP population in aged mice, while it works intact at younger age. Stat5, as a candidate molecule for compensating Stat3 deficiency in thymocytes, has been reported to play a crucial role in the thymic development including maintenance of CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes.28 Together with the Stat3, Stat5 is a key signal transducer for the IL-2 and IL-7 receptor signalling in T cells.29 Furthermore, the activity of Stat5 is much reduced in ageing thymus.29,30 We therefore speculate that the pro-survival signals delivered from IL-2 or IL-7 receptors successfully lead to the expression of downstream targets such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL through Stat5 activation, which is sufficient in young mice even when Stat3 is deficient. However, the expression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL might be unable to be maintained in Stat3-deficient mice at an old age because the activity of Stat5 is dramatically decreased in ageing thymocytes.

We also demonstrated that the susceptibility to apoptosis was enhanced and the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL was significantly reduced in thymocytes from Stat3 knockout mice (Fig. 4c,d). In a study that investigated Bcl-2 expression patterns in the thymus and periphery, it was described that the Bcl-2 expression level is relatively low in double-positive thymocytes, but is significantly up-regulated in SP thymocytes, and mature B and T cells.31 Also, the survival of thymocytes has been suggested to be regulated by Bcl-x protein.32 These findings imply that the survival of thymocytes may be largely regulated by Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression, which is promoted by Stat3 activation.

To determine whether T-cell deficiency in Stat3-deleted mice was attributable to the dysregulation of thymic selection and development; we assessed expression patterns of various T-cell receptor vβ chains (see Supplementary material, Fig. S3). The T-cell receptor vβ expression pattern was generally unvarying between wild-type littermates and the Stat3 knockout group, which implies that Stat3 does not influence the thymic selection process.

To investigate whether the T-cell deficiency in Stat3-knockout mice resulted from increased susceptibility to apoptosis, we performed annexin V staining and TUNEL assays. The numbers of Stat3-deficient T lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis were increased considerably compared with controls (Fig. 5a,b). Several studies performed using T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice have suggested that the expression of Bcl-2 family genes, including Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, was significantly attenuated in T cells upon stimulation with IL-2 or IL-6, or in mouse models of autoimmune disease, such as mice with experimental colitis.11,16,17 Our data provide striking evidence that Stat3 also regulates Bcl-2 family genes in T cells without any prominent cytokine stimulation or induction of autoimmunity (Fig. 6). These results suggest that Stat3 plays a critical role in both maintenance of the resting naive T-cell population and T-cell clonal expansion in response to pro-inflammatory signals through regulation of pro-survival Bcl-2 family genes.

Stat3 also promotes T-cell expansion by enhancing the expression of both pro-survival and proliferative genes.11,17 Hence, we examined whether proliferative potential was decreased in Stat3-knockout cells. Unexpectedly, neither the proportion of cells that were proliferating (Fig. 5a) nor the expression levels of genes that promote cell division, such as cyclins D and E, was significantly decreased in T cells from Stat3-deficient mice (data not shown). Mature SP T lymphocytes are known to enter a ‘resting’ state in which they are quiescent and relatively resistant to apoptosis.33 This suggests that most naive T cells are quiescent. Hence, their maintenance may depend largely on pro-survival signals rather than on stimuli that promote cell division. Our data suggest that Stat3 does not contribute to T-cell proliferation under resting conditions, but could provide resistance against apoptosis by up-regulating Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL gene expression in naive T lymphocytes.

Roles for soluble factors in the maintenance of naive T-cell homeostasis were indicated by the ability of various cytokines to rescue naive T cells from apoptotic cell death.2 In cooperation with signals from T-cell receptors, the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21, which are members of the common γ chain cytokine receptor family, provide pro-survival signals involving PI3K-Akt pathways in naive T lymphocytes.34,35 Furthermore, Akt has been reported to modulate the activity of Stat3 and potentiate the expression of molecules acting downstream of Stat3.36,37 This suggests that various cytokines that activate the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway may confer resistance against apoptosis on resting T cells by promoting Stat3 activation, thereby enhancing Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression.

In conclusion, our results suggest a role for Stat3 in the maintenance of naive T-cell homeostasis. Although we describe an important mechanism by which the T-cell pool is preserved under resting conditions, further studies should address whether Stat3 can provide survival signals to relatively quiescent T or B lymphocytes, such as memory T cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea [NRF] grants [No. 2011-0010571 and 2011-0030739] funded by the Korean government [MESF].

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We thank Dr Shizuo Akira for providing the Stat3-floxed mice. We also thank the Institute for Experimental Animals of the College of Medicine, Seoul National University.

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see:

Disclosures

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Generation of T-cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice.

Figure S2. Analysis of T-cell numbers and the thymic subpopulations in Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE−/− and Stat3WT/WT Lck-CRE+/+ mice.

Figure S3. Analysis of expression pattern in various T-cell receptor vβ chains from thymocytes or splenocytes

References

- 1.Jameson SC. Maintaining the norm: T-cell homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:547–56. doi: 10.1038/nri853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takada K, Jameson SC. Naive T cell homeostasis: from awareness of space to a sense of place. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:823–32. doi: 10.1038/nri2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almeida AR, Rocha B, Freitas AA, Tanchot C. Homeostasis of T cell numbers: from thymus production to peripheral compartmentalization and the indexation of regulatory T cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:239–49. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witherden D, van Oers N, Waltzinger C, Weiss A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Tetracycline-controllable selection of CD4+ T cells: half-life and survival signals in the absence of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. J Exp Med. 2000;191:355–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vivien L, Benoist C, Mathis D. T lymphocytes need IL-7 but not IL-4 or IL-6 to survive in vivo. Int Immunol. 2001;13:763–8. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.6.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maraskovsky E, O'Reilly LA, Teepe M, Corcoran LM, Peschon JJ, Strasser A. Bcl-2 can rescue T lymphocyte development in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice but not in mutant rag-1–/– mice. Cell. 1997;89:1011–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nunez G, Clarke MF. The Bcl-2 family of proteins: regulators of cell death and survival. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:399–403. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaux DL, Cory S, Adams JM. Bcl-2 gene promotes haemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre-B cells. Nature. 1988;335:440–2. doi: 10.1038/335440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, et al. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano T, Ishihara K, Hibi M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene. 2000;19:2548–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durant L, Watford WT, Ramos HL, et al. Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity. 2010;32:605–15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Lee YS, Yu CR, Egwuagu CE. Loss of STAT3 in CD4+ T cells prevents development of experimental autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 2008;180:6070–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milner JD, Brenchley JM, Laurence A, et al. Impaired TH17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLoughlin RM, Jenkins BJ, Grail D, et al. IL-6 trans-signaling via STAT3 directs T cell infiltration in acute inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9589–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501794102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eddahri F, Denanglaire S, Bureau F, et al. Interleukin-6/STAT3 signaling regulates the ability of naive T cells to acquire B-cell help capacities. Blood. 2009;113:2426–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akaishi H, Takeda K, Kaisho T, et al. Defective IL-2-mediated IL-2 receptor α chain expression in Stat3-deficient T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1747–51. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Yoshida N, Takeda J, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Stat3 activation is responsible for IL-6-dependent T cell proliferation through preventing apoptosis: generation and characterization of T cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:4652–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh HM, Yu CR, Golestaneh N, et al. STAT3 protein promotes T-cell survival and inhibits interleukin-2 production through up-regulation of Class O Forkhead transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30888–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.253500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston JA, Bacon CM, Finbloom DS, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT5, STAT3, and Janus kinases by interleukins 2 and 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8705–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman RS, Lourenco PC, Tonner E, et al. Suppression of epithelial apoptosis and delayed mammary gland involution in mice with a conditional knockout of Stat3. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2604–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolbeare F, Gratzner H, Pallavicini MG, Gray JW. Flow cytometric measurement of total DNA content and incorporated bromodeoxyuridine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5573–77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.18.5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popivanova BK, Kitamura K, Wu Y, et al. Blocking TNF-α in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Investig. 2008;118:560–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI32453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi J, Petrie HT. Activation kinetics and off-target effects of thymus-initiated cre transgenes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallandre JR, Brillard E, Crehange G, et al. Role of STAT3 in CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory lymphocyte generation: implications in graft-versus-host disease and antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2007;179:7593–604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antov A, Yang L, Vig M, Baltimore D, Van Parijs L. Essential role for STAT5 signaling in CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cell homeostasis and the maintenance of self-tolerance. J Immunol. 2003;171:3435–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaleco S, Swainson L, Dardalhon V, Burjanadze M, Kinet S, Taylor N. Homeostasis of naive and memory CD4+ T cells: IL-2 and IL-7 differentially regulate the balance between proliferation and Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;171:61–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goswami R, Jabeen R, Yagi R, Pham D, Zhu J, Goenka S, Kaplan MH. STAT6-dependent regulation of Th9 development. J Immunol. 2012;188:968–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriggl R, Topham DJ, Teglund S, et al. Stat5 is required for IL-2-induced cell cycle progression of peripheral T cells. Immunity. 1999;10:249–59. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawelec G, Hirokawa K, Fulop T. Altered T cell signalling in ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1613–37. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007;120:435–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujii Y, Okumura M, Takeuchi Y, Inada K, Nakahara K, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Bcl-2 expression in the thymus and periphery. Cell Immunol. 1994;155:335–44. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma A, Pena JC, Chang B, et al. Bclx regulates the survival of double-positive thymocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4763–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuo CT, Veselits ML, Leiden JM. LKLF: a transcriptional regulator of single-positive T cell quiescence and survival. Science. 1997;277:1986–90. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by γc family cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:480–90. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang Q, Li WQ, Aiello FB, et al. Cell biology of IL-7, a key lymphotrophin. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:513–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivanov VN, Krasilnikov M, Ronai Z. Regulation of Fas expression by STAT3 and c-Jun is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4932–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kortylewski M, Feld F, Kruger KD, et al. Akt modulates STAT3-mediated gene expression through a FKHR (FOXO1a)-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5242–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.