Abstract

Androgen receptor (AR) is a critical effector of prostate cancer (PCa) development and progression. Androgen-dependent PCa rely on the function of AR for growth and progression. Many castration-resistant PCa continue to depend on AR signaling for survival and growth. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is essential for both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant growth of PCa cells. During androgen-dependent growth of prostate cells, androgen-AR signaling leads to the accumulation of rRNA. However, the mechanism by which AR regulates rRNA transcription is unknown. We have found that angiogenin (ANG), the 5th member of the vertebrate-specific, secreted ribonuclease superfamily that is upregulated in PCa, mediates androgen-stimulated rRNA transcription in PCa cells. Upon androgen stimulation, ANG undergoes nuclear translocation in androgen-dependent PCa cells where it binds to the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) promoter and stimulates rRNA transcription. ANG antagonists inhibit androgen-induced rRNA transcription and cell proliferation in androgen-dependent PCa cells. ANG also mediates androgen-independent rRNA transcription. It undergoes constitutive nuclear translocation in androgen-insensitive PCa cells, resulting in a constant rRNA overproduction thereby stimulating cell proliferation. ANG overexpression in androgen-dependent PCa cells enables castration-resistant growth of otherwise androgen-dependent cells. Thus, ANG-stimulated rRNA transcription is not only an essential component for androgen-dependent growth of PCa, but also contributes to the transition of PCa from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth status.

Keywords: Angiogenin, PCa, castration-resistant, ribosomal RNA, androgen receptor

Introduction

Early stage prostate cancer (PCa) requires androgen for growth and thus responds to androgen deprivation therapy. However, the disease progresses to a castration-resistant state that is unresponsive to androgen ablation. Treatment of these castration-resistant PCa patients is generally unsatisfactory. Therefore, the transition from castration-sensitive to castration-resistant growth status is a major obstacle for PCa therapy. The reasons for PCa to progress to castration-resistant status have not been clearly identified but androgen receptor (AR) is thought to play an essential role in this process. AR is a critical effector of PCa development and progression (1). The growth and progression of androgen-dependent PCa strictly depends on the transcription activity of AR. Accumulating evidence shows that castration-resistant PCa continue to depend on AR signaling (2, 3). Extensive efforts have been undertaken to determine the mechanism(s) by which androgens induce PCa cell proliferation and survival (4). It has been shown that AR acts as a master regulator of G1-S phase progression. It induces signals that promote G1 CDK activity and RB protein phosphorylation and inactivation (4). AR-responsive elements have been identified in the promoter region of these and many other androgen-regulated genes (5, 6).

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcription is essential for ribosome biogenesis, protein translation (7) and therefore for cell growth and proliferation of both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant PCa. It has been well documented that androgens regulate rRNA accumulation during androgen-dependent cell growth (8, 9) and that androgen-stimulated rRNA synthesis is a mechanism by which androgens affect growth (10). It is reasonable to hypothesize that a downstream effector might mediate the effect of androgen-AR on rRNA transcription as there has been no evidence that AR binds to ribosomal DNA (rDNA). It is also conceivable that overexpression of this effector may result in overproduction of rRNA and promote castration-resistant growth of PCa.

Angiogenin (ANG) was originally identified as an angiogenic molecule (11) and has been shown to play a role in tumor angiogenesis. Recent evidence indicates that ANG also directly stimulates cancer cell proliferation by enhancing rRNA transcription (12–16). ANG expression is up-regulated in many types of cancers (17), particularly in PCa (16, 18–21). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies have shown that ANG protein is dramatically enhanced in PCa tissues as compared to normal prostate glands (21). ELISA analysis showed that ANG level in the blood is progressively upregulated in PCa patients when they transit from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant, hormone-refractory phenotype (19). IHC analysis of ANG level in a large cohort of radical prostatectomy samples indicated that ANG expression is progressively upregulated in prostatic epithelial cells as they evolve from a benign to an invasive phenotype in the same patients (18). These results clearly demonstrated that ANG expression is correlated to prostate malignancy.

The biological activity of ANG is related to its ability to stimulate rRNA transcription. ANG is normally located in the extracellular matrix and plays a role in mediating cell adhesion (22). When cells have a high metabolic demand and need more ribosomes, ANG is taken up by the cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis (23) and is translocated to the nucleus. Upon reaching the nucleus, ANG accumulates in the nucleolus and stimulates rRNA transcription (24). Nuclear translocation of ANG is thus a metabolic requirement for sustained cell growth and is tightly controlled. However, the normally well-controlled nuclear translocation process of ANG is dysregulated in cancer cells to fulfill the higher metabolic requirement of these cells (15). In case of PCa, ANG-mediated rRNA transcription has been shown to be essential for both establishment and maintenance of AKT-induced prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) (13, 14), as well as for the growth of androgen-insensitive PCa (14, 16, 20, 21, 25). We therefore examined the role of ANG in androgen-stimulated rRNA transcription and in the transition of PCa to castration-resistant growth status. Our results show that ANG is responsible for rRNA transcription in the PCa cells when they are stimulated to proliferate by androgen, indicating an essential role of ANG in PCa growth. Moreover, overexpression of ANG promotes the transition of PCa cells from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth status.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, ELISA, immunofluorescence (IF), Western blotting, and cell counting

RWPE-1 cells were purchased from ATCC and were cultured in keratinocyte serum free medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml EGF (Promega) and 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Sigma). LNCaP cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. PC-3, DU 145 (ATCC), and PC-3M (from Dr. Isaiah J. Fidler, M. D. Anderson Hospital Cancer Cemter) were cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. ANG secretion levels were determined by ELISA as described previously (26). To test the effect of dihydroxytestosterone (DHT) on nuclear translocation of endogenous ANG, cells were washed in phenol red-free medium containing charcoal/dextran-treated (steroid-stripped) FBS (Sigma), incubated in this steroid-free medium for 1 day, and then stimulated by 1 nM DHT (Sigma) for 2 days. IF and Western blotting analyses of nuclear ANG were carried out as described previously (26). ANG monoclonal antibody (mAb) 26-2F was used for IF and polyclonal antibody (pAb) R112 was used for Western analysis. To examine the effect of exogenous ANG on cell proliferation, cells were prepared as described above in steroid-free medium and incubated with 0.1 μg/ml ANG or at the concentrations indicated. Medium was changed and fresh ANG was added every two days. Cells numbers were determined by MTS Cell Proliferation Assay (CellTiter 96® Aqueous, Promega) or with a Coulter counter.

ANG under-expression and over-expression LNCaP cells

Transient ANG knockdown LNCaP cells were prepared using a plasmid encoding an ANG-specific shRNA (5′-GGTTCAGAAACGTTGTTA) as previously described (15). Stable transfectants were selected with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin. ANG overexpression cells were prepared by transfecting LNCaP cells with a pCI-ANG containing the entire ANG coding sequence with the signal peptide (15). Stable transfectants were selected with 2 mg/ml G418.

Northern blotting

RNA were extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen), separated on an agarose/formaldehyde gel, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed to show the 18S rRNA level. The gel was then de-stained and transferred onto a nylon membrane. The probes used for the 47S rRNA (5′-GGTCGCCAGAGGACAGCGTGTCAG-3′) hybridizes with the first 25 nucleotides of the rRNA precursor. The probe used for actin (5′-GGAGCCGTTGTCGACGACGAGCGCGGCG-3′) hybridizes with nucleotides 56–83 of the actin mRNA.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Parent and siRNA knockdown LNCaP cells were cultured in steroid-free medium and stimulated with 1 nM DHT for 1 h. ANG over-expression transfectants were cultured in steroid-free medium and was not stimulated with DHT. Cells were washed with PBS and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at 37 °C for 10 min. After the cross-linking reaction was stopped by 125 mM glycine, cells were collected, washed and re-suspended in the SDS lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) containing 1 x protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The lysates were sonicated five times on a Branson Sonifier 450 with a microtip in 15-sec bursts followed by 2 min of cooling on ice. Cell debris was cleared and the supernatant was diluted 5-fold in ChIP dilution buffer (16.7 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 167 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM EDTA, 1.1% Triton X-100, 0.01% SDS), followed by incubating with 80 μl of protein A-Sepharose slurry for 1 h at 4 °C with agitation. After a brief centrifugation, 10% of the total supernatant was put aside and 1/10 of that material was used as input control. Of the 90% remaining supernatant, half was incubated with R112 polyclonal ANG antibody and the other half with a non-immune rabbit IgG overnight at 4 °C with rotation. Protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) slurry (60 μl) was added to the sample and the reaction mixtures were incubated for another hour. The Sepharose beads were washed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Upstate) and DNA fragments were purified with QIAquick Spin Kit (Qiagen). For PCR reactions, 10% of the immunoprecipitated materials were used as the DNA template in 35 cycles of amplification with the following primer sets. ABE1: forward, 5′-CCCTCGCTCGTTTCTTTC-3′; reverse, 5′-ACTGTGGCACGCCGCTCGGT-3′). ABE2: forward, 5′-TATTGCTACTGGGCTAGGG-3′; reverse, 5′-AACAGACAGGGAGGGAGA-3′. ABE3: forward, 5′-TCTTACTCTGTTTCCTTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-AGAAACACCCAGAAAGAG-3′). UCE: forward, 5′-CGTGTGTCCTTGGGTTGAC-3′; reverse, 5′-GAGGACAGCGTGTCAGCATA-3′. CORE: forward, 5′-CGGGGGAGGTATATCTTTCG-3′; reverse, 5′-GTCACCGTGAGGCCAGAG-3′.

3H-Uridine, 3H-thymidine, and 3H-leucine incorporation

Control (pCI-Neo) and ANG over-expression (pCI-ANG) LNCaP transfectants were seeded in 24-well plate in a density of 1 ×105 cells/cm2 and cultured in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% charcoal/dextran-treated FBS for 4 days. Cells were washed three times and incubated with fresh medium containing 1 μCi/ml 3H-uridine (PerkinElmer, NET367250UC), 3H-thymidine (PerkinElmer, NET027250UC), or 3H-leucine (PerkinElmer, NET46250UC) for 6 h in the absence or presence of 5 μM RAD001 (Novartis). At the end of incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS, precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), washed three times with acetone, and solubilized with 0.2 M NaOH plus 0.3% SDS. After neutralization with 1/5 volume of 1 M HCl, the radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Cell numbers were determined with a Coulter counter from parallel dishes cultured under the same conditions.

Castration

SCID mice (The Jackson Laboratory), 5-weeks-old, were anesthetized and the surgical area were disinfected using Betadine and rinsed with 70% ethanol. An incision was made in the scrotum. Then, an incision was made in the tunica of the first testicle. The testis, vas deferens, and attached testicular fat pad were pulled out of the incision. The blood vessels supplying the testis were cauterized. The testis, vas deferens and fatty tissue were severed just below the site of the cauterization. The tunica on the contralateral side was similarly penetrated, and the procedure repeated. The scrotum incision was closed using wound clips. The mice were given 0.05 mg/kg buprenorphine s.c. as an analgesic once they began to move around slightly. The animals were allowed to recover from surgery for a week before being used in tumor inoculation experiments.

Xenograft growth of LNCaP cells in SCID mice

LNCaP cells were transfected with a control vector pCI-Neo or the ANG expression vector pCI-ANG. Stable transfectants were selected in the presence of 2 mg/ml G418 in complete medium and ANG secretion levels of the pooled transfectants were determined by ELISA. For tumor inoculation, a 0.1 ml of 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences) containing 3 × 106 cells were injected s.c. into the lateral frank region of the mice. Tumor size was measured weekly with a caliber and the volume was calculated as volume = length × width2. The animals were sacrificed after 42 days and the tumors were removed and weighed.

IHC

Xenograft tumor tissue were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4 μm were cut, hydrated, incubated for 30 min with 3% H2O2 in methanol at RT, washed with H2O and PBS, and microwaved in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 10 min. Sections were then blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS for 30 min and incubated with human ANG mAb 26-2F at 30 μg/ml in 1% BSA in PBS at 4°C for 16 h. The DakoCytomation EnVision System was used to visualize the signals.

Results

Androgen stimulates nuclear translocation of ANG in LNCaP cells

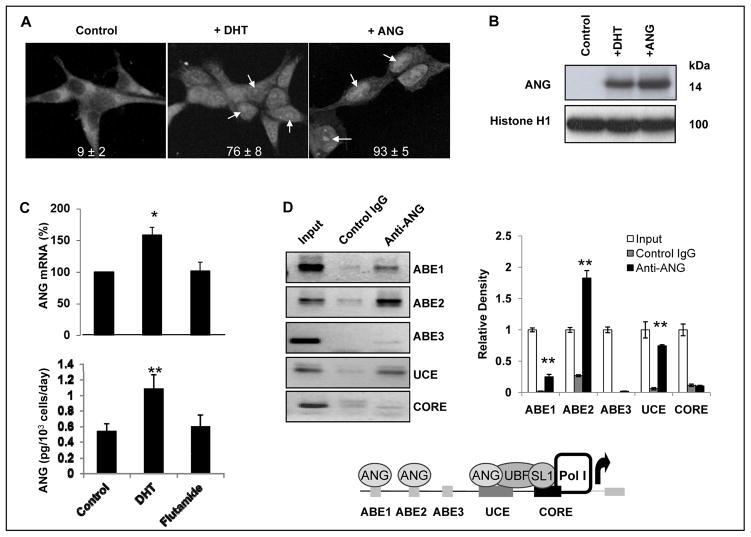

LNCaP cells express a gain-of-function AR and are responsive to androgen stimulation (27). If ANG mediates rRNA transcription of LNCaP cells in response to androgen stimulation, its nuclear translocation should be enhanced when cells are treated with androgen. This is indeed the case. Nuclear ANG was detectable only in 9 ± 2% of untreated LNCaP cells (Fig. 1A, left panel). The percentage of nuclear ANG positive cells increased to 76 ± 8% (Fig. 1A, middle panel, indicated by arrows) after treatment with DHT. Exogenous ANG (0.1 μg/ml) was added to the cells as a positive control (Fig. 1A, right panel), which resulted in a 93 ± 5% positive staining for nuclear ANG. The mAb 26-2F used in this study has a defined epitope recognition site and is specific only to human ANG (28). Western blotting analysis confirmed that nuclear translocation of endogenous ANG in LNCaP cells is stimulated by DHT (Fig. 1B). Moreover, we found that DHT promotes ANG transcription in LNCaP cells. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis indicated that ANG mRNA level was increased by 1.5-fold after DHT treatment (Fig. 1C, top panel). Accordingly, ANG protein level in the medium (secreted ANG) increased from 0.54 ± 0.10 to 1.08 ± 0.19 pg/103 cells per day (Fig. 1C, bottom panel) after DHT treatment. Thus, androgen enhances the expression as well as nuclear translocation of ANG in LNCaP cells. However, antiandrogen has no effect on ANG expression in PCa cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, treatment of LNCaP cells with flutamide did not change the mRNA and the protein levels of ANG. These results resemble earlier findings that ANG expression in estrogen-dependent breast cancer is stimulated by estrogen but is not affected by antiestrogen (29). However, antiestrogen has been shown to inhibit nuclear translocation of ANG in endothelia cells (29) and regulates ANG-induced angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo (30). We have not observed any effect of androgen or antiandrogen on nuclear translocation of ANG in endothelial cells and on the angiogenic activity of ANG. Thus, although both androgen and estrogen seem to upregulate ANG in hormone-dependent prostate and breast cancer cells, respectively, the outcome of hormone ablation therapies in prostate and breast cancers might be different, partially due to the differential response of ANG to antiandrogen and to antiestrogen.

Figure 1.

Effect of DHT on ANG. A, DHT stimulates nuclear translocation of ANG in LNCaP cells. Cells were cultured in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 medium + 10% charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS, and incubated in the absence (left panel) or presence of 1 nM DHT (middle panel) or 0.1 μg/ml ANG (right panel) for 30 min. Cells were fixed and ANG localization was determined by IF staining with ANG mAb 26-2F and Alexa 555-labeled goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG. ANG positive cells were counted in a total of 200 cells in five randomly selected areas. B, Western blotting analysis of nuclear ANG. Nuclear proteins were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting (150 μg per lane) with ANG pAb R112. Histone H1 was used as a loading control. C, Effect of androgen and anti-androgen on ANG expression. Cells were treated with DHT (1 nM) or Flutamide (1 μM) for 2 days. ANG mRNA and secreted ANG protein were determined by qRT-PCR and ELISA, respectively. D, ANG binds to the promoter region of rDNA. Left panels, ChIP analyses of ANG binding to ABE1, ABE2, ABE3, UCE, and CORE regions of the rDNA promoter. PCR primers were designed using MacVector software. The input control in each panel contains 1% of the total DNA. Left panel, ImageJ analysis of the ChIP bands. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.001. Bottom panel, a schematic view of ANG occupancy in the rDNA promoter.

ANG binds at the promoter region of rDNA in LNCaP cells

ANG has been shown to bind to DNA in the nucleus (31). In vitro experiments indicated that ANG binds to DNA sequences with CT-repeats in the promoter region of rDNA (24). ANG binding elements (ABE) have been identified and shown to have ANG-dependent promoter activity in a luciferase reporter assay (24). Three ABE exist in the promoter region of rDNA but it remained unknown whether ANG indeed binds to these ABE in vivo and if it binds, whether this binding enhances rRNA transcription. Therefore we used ChIP experiments to examine in vivo binding of ANG to the rDNA promoter in DHT-treated LNCaP cells. Fig. 1D shows that ANG binds to ABE1, ABE2, and also to the upstream control element (UCE) (Fig. 1D, left panel) where the essential transcription factor UCE binding factor (UBF) binds (32). ImageJ analyses indicated that the occupancy rate of ANG on ABE1, ABE2, ABE3, UCE, and CORE was 2.7 ± 0.5, 18.4 ± 6, 0.18 ± 0.02, 7.6 ± 0.2, and 1.1 ± 0.1%, respectively (Fig. 1D, right panel). The bottom panel of Fig. 1D is a schematic illustration for the binding of ANG to the promoter region of rDNA.

ANG mediates rRNA transcription in androgen-stimulated LNCaP cells

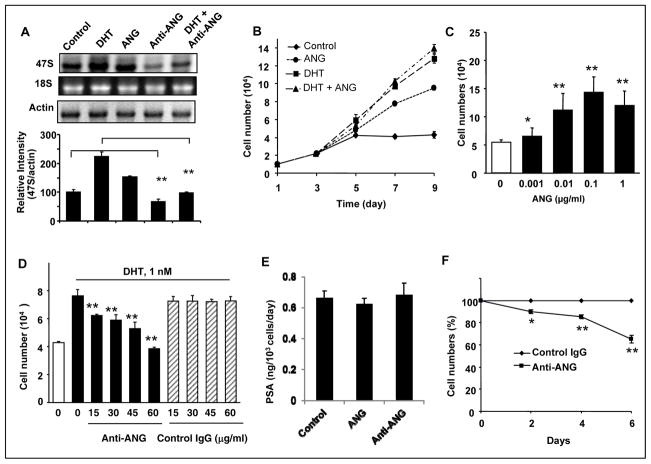

We next examined the role of endogenous ANG in rRNA synthesis in LNCaP cells. Northern blotting analysis was used to detect the steady-state level of 47S rRNA. Fig. 2A shows that DHT and exogenous ANG enhanced rRNA transcription by 2.23- and 1.53-fold, respectively. Significantly, ANG mAb 26-2F inhibited basal and DHT-induced rRNA transcription by 33 and 67%, respectively. These data demonstrated that ANG plays a role in both basal level and DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription in LNCaP cells. Since antibody does not enter the cells, the inhibitory effect of ANG mAb also indicates that it is necessary for ANG to be secreted first in order to mediate rRNA transcription, suggesting that ANG undergoes nuclear translocation via an autocrine or paracrine route.

Figure 2.

ANG mediates DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription and cell proliferation. A, ANG stimulates, and ANG mAb inhibits, rRNA transcription in LNCaP cells. Top panel, Northern blotting analysis of 47S rRNA. Cells were cultured in phenol red-free medium and charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS and incubated with DHT (1 nM), ANG (0.1 μg/ml), ANG mAb 26-2F (60 μg/ml) or a mixture of DHT and 26-2F for 2 h. The level of 47S rRNA was determined by Northern blotting with a probe specific to the initiation site sequence of the rRNA precursor. EB staining of 18S rRNA and Northern blotting of actin mRNA were used as the loading controls. The bar graph at the bottom shows the relative intensity of 47S rRNA to actin mRNA determined by ImageJ. B, ANG stimulates LNCaP cell proliferation in the absence of androgens. Cells were culture in phenol red-free and charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS for 2 day and stimulated with DHT (1 nM), ANG (0.1 μg/ml), or a mixture of the two for the time indicated. Cell numbers were determined with a Coulter counter and with confirmed with MTS assay. C, Dose dependence. ANG was added to the cells and cultured for 4 days. D, ANG mAb 26-2F inhibits DHT-induced cell proliferation. LNCaP cells were stimulated with 1 nM DHT in the presence of 26-2F or a control non-immune IgG at the concentrations indicated for 3 days. E, PSA expression is not dependent on ANG level. LNCaP cells were seeded at 1×105 cells per 35 mm2 dish in RPMI 1640 + 10% FBS and cultured for 2 days. After 2 days, the medium was switched to phenol red-free RPMI 1640 + 10% Charcoal/dextran-treated FBS. The cells were treated with 0.1 μg/ml of ANG or 60 μg/ml of 26-2F for another 2 days. The culture media were collected and PSA level was determined by ELISA. F, ANG mAb inhibits PC-3 cell proliferation. PC-3 cells were cultured in DMEM plus 10% FBS in the presence of 30 μg/ml 26-2F or a control non-immune IgG for the time indicated. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.001.

ANG stimulates LNCaP cell proliferation in the absence of androgen

The findings that ANG stimulates rRNA transcription in the absence of androgen and mediates androgen-stimulated rRNA transcription in LNCaP cells prompted us to look at the effect of ANG on cell proliferation. LNCaP cells, which could not proliferate in steroid-free medium, were stimulated to proliferate by exogenous ANG (Fig. 2B) in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2C). DHT was used as positive control for cell proliferation in these experiments. No additive or synergistic effect was observed when ANG and DHT were added simultaneously, indicating a functional overlap between ANG and DHT. ANG-stimulated rRNA transcription might present a mechanism by which PCa cells bypass androgen-AR signaling pathway.

Endogenous ANG is required for androgen-stimulated LNCaP cell proliferation

The essential role of ANG in rRNA transcription in response to androgen-AR signaling suggested that ANG may be required for androgen to induce cell proliferation. Fig. 2D shows that ANG mAb 26-2F inhibited DHT-induced proliferation of LNCaP cells in a dose dependent manner, indicating that ANG is required for LNCaP cells to proliferate in response to androgen-AR signaling. Both exogenous ANG and ANG mAb did not alter PSA expression in LNCaP cells (Fig. 2E), suggesting that AR-stimulated gene transcription is not regulated by ANG. ANG mAb also inhibited proliferation of androgen-independent PC-3 cells (Fig. 2F). These results demonstrate that ANG is essential for cell growth of both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant PCa.

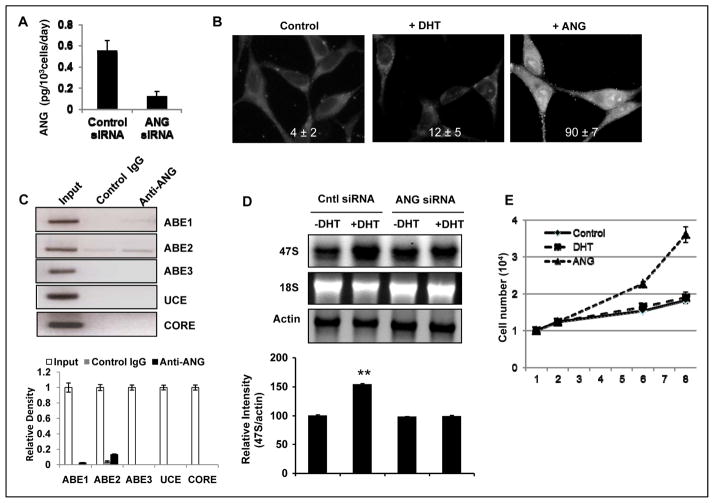

ANG siRNA inhibits DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription and proliferation of LNCaP cells

To confirm the role of endogenous ANG in rRNA transcription, we used a plasmid-mediated siRNA (15) to knock down ANG expression in LNCaP cells and examined the resultant changes in rRNA transcription. ELISA analysis indicated that the amount of secreted ANG in control and ANG-specific siRNA transfected cells was 0.55 ± 0.1 and 0.12 ± 0.05 pg/103 cells per day (Fig. 3A), representing a 79 % knockdown efficiency. ANG knockdown is accompanied by a decrease in DHT-stimulated nuclear translocation of ANG (Fig. 3B). Only 12 ± 5% of the ANG knockdown cells were positive for nuclear ANG upon DHT stimulation (Fig. 3B, middle panel), which is 6.3-fold lower than that in control LNCaP cells (76 ± 8%, Fig 1A). The percentage of cells with a positive nuclear ANG in the presence of exogenous ANG was 90 ± 7% (Fig. 3B, right panel), which is not significantly different from that of the parent cells (93 ± 5%, Fig. 1A, right panel), indicating that the ability of the cells to uptake exogenous ANG was not altered after endogenous ANG was knocked down. A decrease in nuclear ANG resulted in a lower occupancy of ANG at rDNA promoters (Fig. 3C), and is accompanied with a reduced capacity of the cells to respond to DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription (Fig. 3D). ANG occupancy in the UCE was not detectable in ANG knockdown cells and that at ABE1 and ABE2 was 0.35 and 1.38% (Fig. 1C), which is 7.7- and 13.3-fold lower than that in control cells (Fig. 1D). Knockdown of ANG completely abolished the activity of DHT in stimulating rRNA transcription (Fig. 3D). DHT was able to stimulate transcription of 47S rRNA in cells treated with a control siRNA but failed to do so in cells transfected with an ANG-specific siRNA (Fig. 3D). The reasons that the basal transcription of rRNA in unstimulated cells did not decrease in ANG knockdown cells (Fig. 3D, lanes 1 and 3) could be due to the remaining 21% of the ANG after siRNA treatment. This amount of ANG might suffice in maintaining the basal transcription but might be inadequate to meet the metabolic demand imposed by DHT treatment. The efficiency of the mAb in inhibiting the biological activity of ANG was thus better than that of siRNA. The concentration of the antibody used in these experiments was 60 μg/ml, which was at least 100-fold higher than the maximum possible concentration of endogenous ANG secreted from the cells. It is conceivable that all of the secreted ANG could be potentially neutralized by the antibody. However, 21% of the endogenous ANG remained in the siRNA knockdown cells. The discrepancy seen between ANG mAb and siRNA is most likely caused by the difference in the remaining ANG activities in the two systems. These results confirmed that ANG is necessary for enhanced rRNA transcription in LNCaP cells when they are stimulated to grow by androgen. Consistently, DHT is no longer able to stimulate proliferation in ANG knockdown LNCaP cells (Fig. 3E), further demonstrating that ANG is necessary for the growth-stimulatory function of androgens.

Figure 3.

ANG siRNA abolishes DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription and cell proliferation. A, ELISA analysis of secreted ANG level in control and ANG siRNA-transfected cells. B, DHT-stimulated nuclear translocation of ANG is decreased in ANG knockdown cells. Cells were cultured in steroid-free medium for 24 h and stimulated with 1 nM DHT (middle) or 0.1 μg/ml ANG for 30 min. IF detection of ANG was carried out with 26-2F and Alexa 488-labeled goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. ANG positive cells were counted in a total of 200 cells in five randomly selected areas. C, ChIP analysis of ANG occupancy in rDNA promoter. ANG knockdown cells were cultured in steroid-free medium for 24 h and stimulated with 1 nM DHT for 1 h. ChIP were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 1D. Top panel, ChIP bands; bottom panel, ImageJ analysis. D, ANG siRNA abolishes DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription. Top panel, Northern blotting analysis of 47S rRNA in control and ANG siRNA-transfected cells with actin mRNA as loading controls. Bottom panel, relative intensity of 47S rRNA to actin mRNA determined by densitometry. **, p<0.01. E, ANG siRNA abolishes DHT-stimulated cell proliferation. ANG knockdown cells were cultured in steroid-free medium and stimulated with 1 nM DHT or 0.1 μg/ml ANG. Cell numbers were determined with a Coulter counter. Data shown are means ± SD of triplicates in a representative experiment.

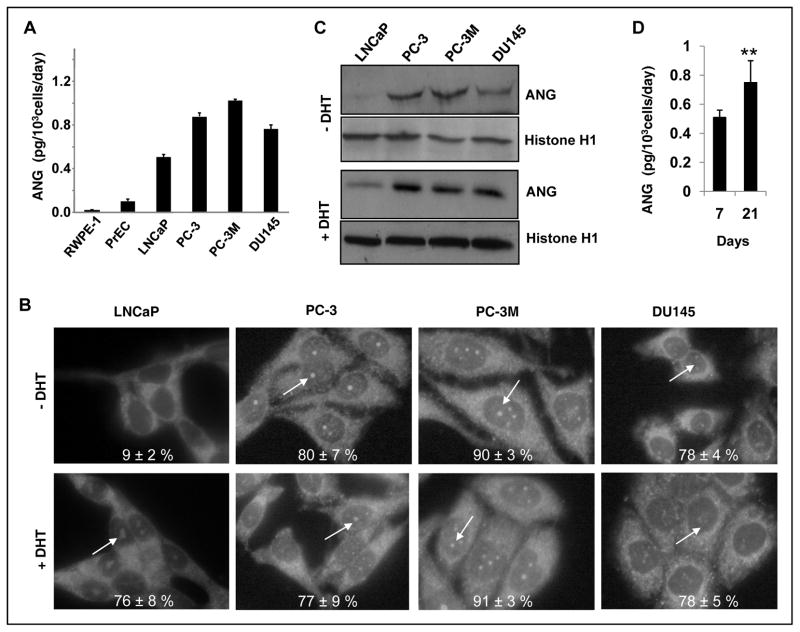

Exogenous ANG has no effect on androgen-independent PCa cells

The finding that ANG stimulates LNCaP cell proliferation in the absence of androgen led us to hypothesize that upregulation of ANG contributes to the development of androgen-independent PCa. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the effect of exogenous ANG on cell proliferation of androgen-independent PCa cells including PC-3, PC-3M and DU145. We found that exogenous ANG had no effect on proliferation of these cells (data not shown). Since endogenous ANG has already been shown to play a role in PC-3 cell proliferation (Fig. 2F and ref. (16), a plausible explanation would be that these androgen-independent cells already express adequate amount of ANG and that their nuclei have already been saturated by endogenous ANG. We therefore measured ANG expression levels by ELISA in these cells as well as in the normal prostate epithelial cells (RWPE-1 and PrEC). Indeed, androgen-independent PC-3, PC-3M and DU145 cells secreted more ANG than did androgen-dependent LNCaP cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, all four PCa cell lines secreted a significantly higher amount of ANG than did the normal prostate epithelial cells RWPE-1 and PrEC.

Figure 4.

Constant nuclear translocation of ANG in androgen-insensitive PCa cells. A, Upregulation of ANG in human PCa cells. Secreted ANG proteins in normal human prostate epithelial cells and PCa cells were determined by ELISA. B, Nuclear translocation of ANG in PCa cells. LNCaP, PC-3, PC-3M, and DU145 cells were cultured in their respective media supplemented with 10% FBS for two days. FBS was then replaced with charcoal/dextran-stripped serum and the cells were cultured in the absence or presence of DHT (1 nM) for 2 days. IF of ANG was carried out with ANG mAb 26-2F (50 μg/ml) and Alexa 488-labeled goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG (1:100 dilution) as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. Nucleolar ANG was indicated by arrows. C, Western blotting analysis of nuclear ANG. Nuclear proteins were extracted from the cells cultured in the absence (top two panels) and presence (bottom two panels) of DHT and analyzed by Western blotting (150 μg per lane) with ANG pAb R112. Histone H1 was used as a loading control. D, ANG expression is upregulated in ANG knockdown LNCaP cells after prolonged culture in steroid-free medium. Control and ANG siRNA transfectants were continuously cultured in steroid-free medium for one or three weeks without subculture. Medium was changed every two days. ANG secreted into the medium between day 6 and day 7, and between day 20 and day 21 was determined by ELISA. Cell number was determined from parallel dishes by a Coulter counter.

ANG is constitutively translocated to the nucleus of androgen-independent PCa cells

We next examined nuclear translocation of ANG in those cells in the presence or absence of androgen. ANG was found to be constitutively translocated to the nucleolus of the three types of androgen-independent cells both in the absence and presence of DHT (Fig. 4B). Western blotting analysis (Fig. 4C) showed that in PC-3, PC-3M and DU145 cells, ANG protein was detected in the nuclear proteins extracted from cells cultured in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of androgen. LNCaP cells were included in this experiment as a control for androgen-stimulated nuclear translocation of ANG, and the results confirmed the finding in Fig. 1A that androgen stimulates nuclear translocation of ANG in LNCaP cells. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that upregulation of ANG and constitutive nuclear translocation is associated with castration-resistant growth status of PCa cells. Consistently, we found that ANG expression in LNCaP cells was upregulated in prolonged culture under hormone- and steroid-free culture (Fig. 4D). The level of secreted ANG in LNCaP cells cultureed in phenol red-free, charcoal/dextran-treated FBS was 0.75 ± 0.15 pg per103 cells per day on day 21, which is 47% higher than that on day 7 (0.51 ± 0.05 pg/103 cells/day, Fig. 4D).

Overexpression of ANG stimulates castration-resistant growth of LNCaP cells

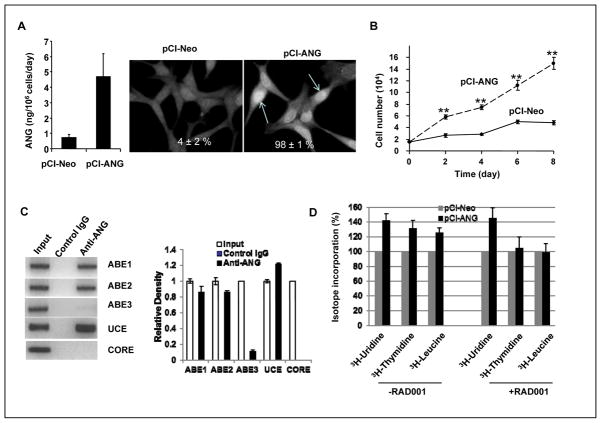

To determine whether upregulation of ANG is correlated with the development of castration resistance of PCa, we examined the effect of ANG overexpression on LNCaP cell proliferation in the absence of androgens. ANG expression vector pCI-ANG that carries the human ANG cDNA under CMV promoter and the control vector pCI-Neo were transfected into LNCaP cells and stable transfectants expressing 6.6-times higher ANG were selected (Fig. 5A, left) and shown to have increased nuclear accumulation of endogenous ANG (Fig. 5A, right panels, indicated with arrows). The percentage of positive cells for nuclear ANG increased from 4 ± 2% in the pCI-Neo vector control transfectants to 98 ± 1% in pCI-ANG transfectants in the absence of DHT. ANG over-expression stimulated LNCaP proliferation in culture in the absence of androgen (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

ANG over-expression promotes androgen-independent growth of LNCaP cells. A, Endogenous ANG in stable vector control (pCI-Neo) and ANG (pCI-ANG) transfectants. Left panel, ELISA analysis of secreted ANG protein in vector control and ANG transfectants. Right panels, IF detection of cellular ANG in control and ANG transfectants. Cells positive for nuclear ANG were counted in 200 cells in 5 randomly selected areas. B, ANG overexpression promotes LNCaP proliferation in vitro in the absence of androgen. Cells were cultured in phenol red-free medium and charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS. Cell numbers were determined with a Coulter counter. Data shown are means ± SD of triplicates in a representative experiment. C, ChIP analysis of ANG occupancy in rDNA promoter. ANG over-expression cells were cultured in steroid-free medium for 24 h and ChIP analyses were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 1D. Right panel, ChIP bands; right panel, ImageJ analysis. D, RAD001 inhibits ANG-stimulated DNA synthesis and protein translation but not RNA transcription. Vector (pCI-Neo) and ANG (pCI-ANG) transfectants were cultured in steroid-free medium and were pulsed with 1 μCi 3H-uridine, 3H-thymidine, or 3H-leucine for 6 h. Radioisotope incorporated into TCA-insoluble fraction was normalized to cell number and the value from the vector control transfectants was set as 100. Data shown are means ± SD of triplicates.

Consistently, rDNA promoter occupancy by ANG was significantly enhanced in ANG over-expression cells (Fig. 5C, left panel). ChIP analyses indicate that the percentage of ANG-bound ABE1, ABE2, and UCE was 8.6 ± 0.8, 8.2 ± 0.2, and 12.2 ± 0.14%, respectively (Fig. 5C, right panel), which is similar to the promoter occupancy in DHT-stimulated parent LNCaP cells (Fig. 1D). 3H-uridine incorporation experiments indicated that ANG over-expression cells have enhanced rRNA synthesis rate as compared to that of vector control (Fig. 5D). DNA and protein synthesis rates were concurrently enhanced in ANG over-expression cells as shown by 3H-thymidine and 3H-leucine incorporation experiment (Fig. 5D, left). RAD001, a water soluble analogue of rapamycin, inhibited ANG-induced protein and DNA synthesis but not RNA synthesis (Fig. 5D, right). These results suggest that ANG-stimulated RNA transcription is mTOR-insensitive but that of DNA synthesis and protein translation require the mTOR activity. This is consistent with our hypothesis that ANG-mediated rRNA transcription and mTOR-mediated ribosomal protein synthesis are both necessary for cell proliferation.

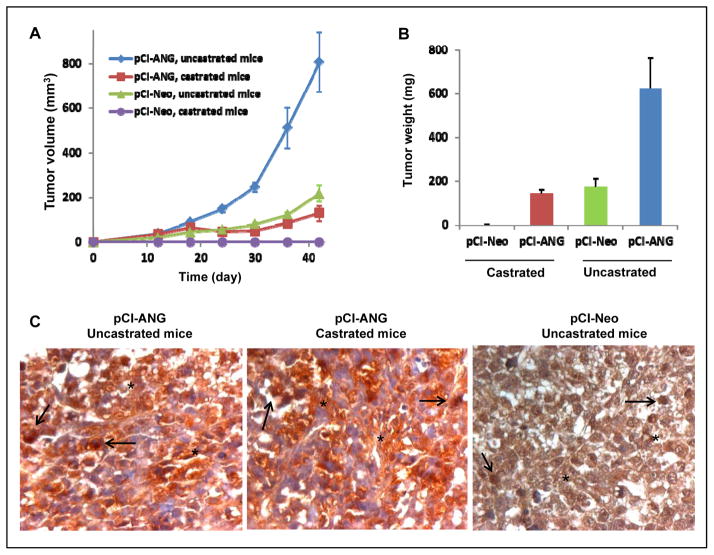

When these cells were inoculated into SCID mice, both the vector and ANG transfectants were able to establish tumors with a 100% tumor take rate in uncastrated mice (n=6). It is noticeable that the tumor growth rate in animals inoculated with ANG transfectants was much greater than in those inoculated with the vector control transfectants (Fig. 6A). Consistently, the tumor weight derived from ANG overexpression cells (0.62 ± 0.35 g) was 3.6-times bigger than that derived from the vector transfectants (0.17 ± 0.10 g) (Fig. 6B). To determine whether ANG overexpression promotes androgen-independent proliferation in vivo, these transfectants were inoculated into castrated SCID mice. None of the animals (n=6) inoculated with vector transfectants had palpable tumors in castrated mice, whereas 5 of the 6 castrated mice developed tumors when inoculated with ANG transfectants, indicating that ANG over-expression permits LNCaP tumor establishment in the absence of androgen. We noted that the tumor growth rate in castrated mice was slower than that in uncastrated mice (Fig. 6A), and that the tumor weight from the castrated animals (0.14 ± 0.95 g) was lower than that from the uncastrated animal (0.62 ± 0.35) (Fig. 6B), indicating that androgen still has an effect on in vivo growth of ANG transfectants. IHC showes that ANG expression and localization in the tumors derived from ANG transfectants grown in uncastrated (Fig 6C, left) and castrated (Fig. 6C, center) mice are indistinguishable. Both nuclear (arrows) and extracellular ANG (stars) were prominent and much stronger than that in the tumor tissues derived from vector control transfectants grown in uncastrated mice (Fig. 6C, right). These results indicate that ANG over-expression results in constant nuclear translocation of ANG in LNCaP cells even in castrated mice. They also indicate that ANG over-expression enables LNCaP cells to proliferate in the absence of androgen both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that over-expression of ANG contributes to the transition of PCa to castration resistance. These results, together with the finding that ANG is enhanced in the nucleus of androgen-independent cells, suggest that upregulation and enhanced nuclear translocation of ANG will result in an excessive supply of rRNA, which may contribute to the development of castration resistance.

Figure 6.

ANG overexpression is correlated with castration-resistant growth of LNCaP cells in vivo. A, Xenograft growth of vector control and ANG transfectants in castrated SCID mice. A mixture of 70 μl cell suspension (1×106 cells) and 30 μl Matrigel was injected s.c. per mouse (6 per group). The mice were castrated or sham-operated at the same time. Tumors sizes were measured with a caliper and recoded in mm3 (length × width2). B, Wet weight of dissected tumors. C, Expression and localization of human ANG detected by IHC with mAb 26-2F. Representative nuclear and extracellular localizations of ANG were indicated with black arrows and stars, respectively. **, p<0.001.

Discussion

There are two major findings of this paper. The first is that ANG mediates DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription in androgen-sensitive LNCaP cells. The second is that ANG over-expression permits LNCaP cell growth in the absence of androgen. These results indicate that ANG is a critical player in the growth of both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant PCa. More importantly, these results also indicate that ANG plays an active role in the transition of PCa from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth status.

Transition to castration-resistant growth is a life threatening development of PCa. The median survival of castration-resistant PCa is 10–20 months (33). Recent advancements in chemotherapy have provided only palliative but not survival benefit (34, 35). A major challenge in developing effective therapeutics is the heterogeneous genetic, epigenetic and cellular pathogenesis of PCa (36, 37). For examples, constitutive AR function (1), AKT activation and PTEN loss (38), aberrant activation of multiple growth factor signaling pathways (36), upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 (39), loss of cell cycle regulatory proteins (40), and epigenetic alterations (37) have all been identified as PCa etiology. Therefore, targeting multiple pathways involved in cancer development and progression are thought to provide better chances for success (41). An alternative approach would be to identify a down-stream target that is common to multiple upstream pathways. The results we present in this paper have identified ANG-mediated rRNA transcription as such a target.

rRNA is essential for ribosome biogenesis that is critical for protein translation (42). Ribosomes have been traditionally considered as merely having house-keeping functions (43). In fact, ribosomes are essential for correctly and efficiently producing all proteins in the cells and their abnormality has been associated to cancers (44). For cancer cells, ribosome biogenesis needs to be enhanced to meet the high metabolic demand of these cells. A functional ribosome is composed, in an equal molar ratio, of 79 ribosomal proteins and 4 rRNA molecules (45). It is well known that, in response to growth signals such as upon androgen stimulation of prostate cells, the production of ribosomal proteins is enhanced through the mTOR-S6K pathway. However, it was unclear how rRNA is proportionally increased. Our work has shown that under these circumstances rRNA transcription is enhanced by ANG. We show that DHT not only stimulates nuclear translocation of ANG in LNCaP cells (Fig. 1A), but also upregulates ANG expression (Fig. 1C). We also show that nuclear ANG binds to both ABE and UCE at the promoter region of rDNA (Fig. 1D) and promotes rRNA transcription (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that in androgen-dependent PCa cells, it is ANG that stimulates rRNA transcription so that ribosome biogenesis can take place. Thus, ANG is a permissive factor for DHT to induce cell proliferation. This contention has been proven by the findings that both ANG mAb (Fig. 2A) and siRNA (Fig. 3D) inhibit DHT-stimulated rRNA transcription in LNCaP cells. Consistently, both mAb and siRNA of ANG inhibit DHT-stimulated LNCaP cell proliferation (Fig. 2D and 3E).

Another significant finding of this paper is that ANG is a contributing factor for the development of castration-resistant PCa. We have found that ANG overexpression enable androgen-independent growth of otherwise androgen-dependent LNCaP cells both in vitro (Fig. 5B) and in vivo (Fig. 6A). These results strongly suggest that elevated level of ANG contributes to the transition of PCa from androgen-dependent growth to castration-resistant growth. It is unclear at present whether or not AR continues to play a role in ANG-stimulated growth of castration-resistant PCa. We are currently investigating whether ANG is able to stimulate nuclear translocation of AR in the absence of androgen and whether the transcriptional activity of AR requires the participation of ANG action. A more in-depth understanding of the crosstalk between the ANG pathway and the AR pathway will likely reveal the mechanism by which ANG overexpression stimulates androgen-independent growth of PCa. Nevertheless, the present evidence has clearly demonstrated that upregulation of ANG is able to promote androgen-independent growth of androgen-sensitive PCa cells. Thus, the progressive upregulation of ANG observed in PCa (18) may not only be a passive response of the cells to an increased metabolic demand, but also an active participant in the development and progression of this disease. Some early reports also support an active role of ANG in PCa. For examples, ANG has been shown to be the most significantly upregulated gene in the PIN tissue in murine prostate-restricted AKT kinase transgenic (MPAKT) mice (19). The role of ANG in the prostate in MPAKT mice has been shown to stimulate rRNA transcription to permit AKT-induced cell growth (13). As such, ANG-stimulated rRNA transcription might be a common pathway for a variety of growth stimuli in PCa. The uncontrolled growth inflicted by genetic, epigenetic and cellular abnormalities likely all requires ANG to participate. Thus, ANG is a molecular target for PCa drug development. ANG antagonists would be effective in inhibiting both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant growth of PCa. More importantly, this type of inhibitors would also be effective in preventing the transition of PCa from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth status.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was support by NIH grant R01 CA105241.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Taplin ME. Androgen receptor: role and novel therapeutic prospects in prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:1495–508. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.9.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Sawyers CL, Scher HI. Targeting the androgen receptor pathway in prostate cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:440–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balk SP, Knudsen KE. AR, the cell cycle, and prostate cancer. Nucl Recept Signal. 2008;6:e001. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q, Li W, Liu XS, Carroll JS, Janne OA, Keeton EK, et al. A hierarchical network of transcription factors governs androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer growth. Mol Cell. 2007;27:380–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Mani RS, Cao Q, Brenner CJ, Cao X, Wang X, et al. An integrated network of androgen receptor, polycomb, and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:443–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenwald IB. Deregulation of protein synthesis as a mechanism of neoplastic transformation. Bioessays. 1996;18:243–50. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mainwaring WI, Wilce PA. The control of the form and function of the ribosomes in androgen-dependent tissues by testosterone. Biochem J. 1973;134:795–805. doi: 10.1042/bj1340795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mainwaring WI, Derry NS. Enhanced transcription of rRNA genes by purified androgen receptor complexes in vitro. J Steroid Biochem. 1983;19:101–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabler RL, Srinivasan A, Taylor LJ, Mowad J, Rothblum LI, Cavanaugh AH. Androgen regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis in LNCaP cells and rat prostate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;59:431–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fett JW, Strydom DJ, Lobb RR, Alderman EM, Bethune JL, Riordan JF, et al. Isolation and characterization of angiogenin, an angiogenic protein from human carcinoma cells. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5480–6. doi: 10.1021/bi00341a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirukawa S, Olson KA, Tsuji T, Hu GF. Neamine inhibits xenografic human tumor growth and angiogenesis in athymic mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8745–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibaragi S, Yoshioka N, Kishikawa H, Hu JK, Sadow PM, Li M, et al. Angiogenin-stimulated Ribosomal RNA Transcription Is Essential for Initiation and Survival of AKT-induced Prostate Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:415–24. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibaragi S, Yoshioka N, Li S, Hu MG, Hirukawa S, Sadow PM, et al. Neamine inhibits prostate cancer growth by suppressing angiogenin-mediated ribosomal RNA transcription. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1981–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji T, Sun Y, Kishimoto K, Olson KA, Liu S, Hirukawa S, et al. Angiogenin is translocated to the nucleus of HeLa cells and is involved in ribosomal RNA transcription and cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1352–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshioka N, Wang L, Kishimoto K, Tsuji T, Hu GF. A therapeutic target for prostate cancer based on angiogenin-stimulated angiogenesis and cancer cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14519–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606708103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tello-Montoliu A, Patel JV, Lip GY. Angiogenin: a review of the pathophysiology and potential clinical applications. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1864–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katona TM, Neubauer BL, Iversen PW, Zhang S, Baldridge LA, Cheng L. Elevated expression of angiogenin in prostate cancer and its precursors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8358–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majumder PK, Yeh JJ, George DJ, Febbo PG, Kum J, Xue Q, et al. Prostate intraepithelial neoplasia induced by prostate restricted Akt activation: the MPAKT model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7841–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232229100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson KA, Byers HR, Key ME, Fett JW. Prevention of human prostate tumor metastasis in athymic mice by antisense targeting of human angiogenin. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3598–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson KA, Byers HR, Key ME, Fett JW. Inhibition of prostate carcinoma establishment and metastatic growth in mice by an antiangiogenin monoclonal antibody. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:923–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soncin F. Angiogenin supports endothelial and fibroblast cell adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2232–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moroianu J, Riordan JF. Nuclear translocation of angiogenin in proliferating endothelial cells is essential to its angiogenic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1677–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu ZP, Tsuji T, Riordan JF, Hu GF. Identification and characterization of an angiogenin-binding DNA sequence that stimulates luciferase reporter gene expression. Biochemistry. 2003;42:121–8. doi: 10.1021/bi020465x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kao RY, Jenkins JL, Olson KA, Key ME, Fett JW, Shapiro R. A small-molecule inhibitor of the ribonucleolytic activity of human angiogenin that possesses antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10066–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152342999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kishimoto K, Liu S, Tsuji T, Olson KA, Hu GF. Endogenous angiogenin in endothelial cells is a general requirement for cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:445–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Kawinski E, Karr JP, Rosenthal H, Chu TM, et al. LNCaP model of human prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1809–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chavali GB, Papageorgiou AC, Olson KA, Fett JW, Hu G, Shapiro R, et al. The crystal structure of human angiogenin in complex with an antitumor neutralizing antibody. Structure. 2003;11:875–85. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson UW, Abrahamsson A, Dabrosin C. Angiogenin regulation by estradiol in breast tissue: tamoxifen inhibits angiogenin nuclear translocation and antiangiogenin therapy reduces breast cancer growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3659–69. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aberg UW, Saarinen N, Abrahamsson A, Nurmi T, Engblom S, Dabrosin C. Tamoxifen and flaxseed alter angiogenesis regulators in normal human breast tissue in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu G, Xu C, Riordan JF. Human angiogenin is rapidly translocated to the nucleus of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and binds to DNA. J Cell Biochem. 2000;76:452–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000301)76:3<452::aid-jcb12>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badet J, Soncin F, Guitton JD, Lamare O, Cartwright T, Barritault D. Specific binding of angiogenin to calf pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:8427–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berthold DR, Sternberg CN, Tannock IF. Management of advanced prostate cancer after first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8247–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, Lara PN, Jr, Jones JA, Taplin ME, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mimeault M, Batra SK. Recent advances on multiple tumorigenic cascades involved in prostatic cancer progression and targeting therapies. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1–22. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz WA, Hatina J. Epigenetics of prostate cancer: beyond DNA methylation. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:100–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trotman LC, Niki M, Dotan ZA, Koutcher JA, Di Cristofano A, Xiao A, et al. Pten dose dictates cancer progression in the prostate. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furuya Y, Krajewski S, Epstein JI, Reed JC, Isaacs JT. Expression of bcl-2 and the progression of human and rodent prostatic cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:389–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Marzo AM, Marchi VL, Epstein JI, Nelson WG. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1985–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65517-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta RA, DuBois RN. Combinations for cancer prevention. Nat Med. 2000;6:974–5. doi: 10.1038/79664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moss T. At the crossroads of growth control; making ribosomal RNA. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moss T, Langlois F, Gagnon-Kugler T, Stefanovsky V. A housekeeper with power of attorney: the rRNA genes in ribosome biogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:29–49. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6278-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruggero D, Pandolfi PP. Does the ribosome translate cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:179–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nazar RN. Ribosomal RNA processing and ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:457–65. doi: 10.1080/15216540400010867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]