Abstract

Purpose

To collect human oocytes from ovaries removed as part of surgical treatment for endometrial carcinoma, and to induce in vitro maturation of such oocytes to obtain material for research on human ovarian aging.

Methods

Design: Prospective clinical study. Setting: University Hospital. Patients: Eight patients aged 35–44 years with a preoperative diagnosis of Stage I endometrial cancer agreed to participate in this project. Interventions: Surgically removed ovaries were punctured; oocytes were collected from follicular fluid and matured in vitro. Immunofluorescent detection of microtubules and DNA labeling were performed after in vitro maturation. Main Outcome Measures: Number of oocytes collected and their in vitro maturation stage.

Results

In total, 87 oocytes were collected, 11 of which had completed metaphase II. Of the oocytes collected, 75 % were from three patients in their 30s, while the remaining 25 % were from five patients in their 40s. Several stages of oocytes were collected and the detection of microtubule arrangement and chromatin in various stages using fluorescence was possible.

Conclusion

Material for research on human ovarian aging can be obtained from ovaries removed during surgery for endometrial cancer.

Keywords: Human oocytes, In vitro maturation, Microtubules

Introduction

The axiom “oocyte quality controls almost all of a couple’s reproductive potential” is widely accepted in reproductive medicine. Oocyte quality begins to decrease after age 30, and drops rapidly after age 35 [6, 7]. In older women, the meiotic spindle is frequently abnormal [1], and aging-associated oocyte aneuploidy and meiotic spindle defects have been described in mice [12]. However, to date, there are few studies investigating the association between aging and oocyte function. Studies on human oocytes are even less common. Considering the number of women over age 40 who wish to have children but are infertile, it is clear that additional studies on the functional decline of oocyte quality associated with aging are urgently needed.

One reason for the paucity of relevant research to date is the challenge of developing animal models to simulate the aging of human oocytes, and it is also difficult to obtain human oocytes for research purposes. There are ethical problems associated with the use of mature oocytes obtained through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for research, and the laws governing such use vary from country to country [9]. Additionally, a lower number of oocytes in women over age 30 complicates the extension of oocyte research to include the period preceding menopause.

In 2004, Revel et al. reported that human oocytes were obtained from an ovary that was resected during surgery for uterine endometrial cancer [11]. In their report, the ovary of a 43-year-old patient provided 17 oocytes after ovarian puncture, and eight embryos were obtained by in vitro maturation (IVM). Uterine endometrial cancer occurs in women over a wide age range, including our target age of 30–50 years. Therefore, we hypothesized that we could investigate aging-related changes in oocyte function by using ovaries resected from patients with endometrial cancer. However, a thorough examination of oocytes obtained from an ovary resected at a random point during the menstrual cycle had not previously been performed. Here we report the collection of human oocytes removed during surgery for endometrial carcinoma, which then underwent IVM to produce matured human oocytes for research. The organization of DNA and microtubules in the post-IVM oocytes was assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Materials

Eight patients from the age of 35 to 44 years with a preoperative diagnosis of Stage I endometrial cancer agreed to participate in this study. There were three patients in their 30s (two patients aged 35 years, Patients 1 and 8; one patient aged 38 years, Patient 5) and five patients in their 40s (two patients aged 41 years, Patients 3 and 4; two patients aged 42 years, Patients 6 and 7; one patient aged 44 years, Patient 2). All eight women had almost regular menstrual cycles before surgery.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tohoku University, and written informed consent was obtained prior to surgery.

Methods

After laparotomy under general anesthesia, surgeons confirmed that the patients had no macroscopic evidence of progressive cancer. After cytological sampling of the pelvic cavity, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed. And, the adnexa were maintained in warm phosphate-buffered saline, and immediately transported to the laboratory. We punctured macroscopically identifiable ovarian follicle-like structures with a 19-gauge needle and aspirated the follicular fluid (Fig. 1). We punctured each ovary approximately 15 times, and examined the collected oocytes under the microscope. IVM was promoted using M199 medium (Gibco Labs, Grand Island, NY) with 20 % Systemic Serum Substitute (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) and 75 mIU/mL of recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (rFSH, Fertinome P, Serono, Tokyo, Japan) at 37 °C in an atmosphere with 5 % oxygen and 90 % nitrogen for 24 to 48 h. Cumulus cells were removed from oocytes after culture and the maturation stage of the oocytes was estimated. We fixed the oocytes that released a polar body after 24 h of IVM, and fixed all remaining oocytes after 48 h in IVM conditions. Fixation was carried out as previously described [3]. In brief, after removing the cumulus cells, oocytes were incubated in Buffer M (25 % (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 1 mM glycol ether diamine tetraacetic acid [EGTA], 50 mM imidazole hydrochloride, and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol; pH 6.8) at 37 °C for 30 min. The oocytes were then placed on glass coverslips and fixed with −20 °C methanol. Immunofluorescence staining to detect microtubules and DNA visualization with Hoechst 33342 were performed as previously described [10]. Briefly, microtubules were labeled with a mixture of monoclonal antibodies against β-tubulin (clone 2-28-33; diluted 1:100; Sigma) and acetylated α-tubulin (clone 6-11-B1; diluted 1:100; Sigma). Primary antibodies were detected using fluorescein-conjugated goat immunoglobulin G (IgG; diluted 1:40; Zymed, San Francisco, CA). DNA was detected after labeling with 10 mg/mL of Hoechst 33342.

Fig. 1.

Oocyte collection from resected ovaries. a A 19-gauge needle was used to puncture the ovary approximately 15 times in order to aspirate follicular fluid containing oocytes. b Immature oocytes collected from follicular fluid. c Oocytes after in vitro maturation (IVM)

Results

The number of oocytes collected from each patient is presented in Table 1. In total, we obtained 87 oocytes from eight patients. We obtained 65 oocytes (an average of 21.7 per patient) from the three women in their 30s. By contrast, we obtained only 22 oocytes (an average of 4.4 per patient) from the eight women in their 40s. Of the 87 oocytes, only 11 (all from women aged 35 years) reached metaphase II (MII) after IVM. By contrast, a significant number of oocytes were arrested in maturation, even with IVM. With respect to the developmental stage, the most common phenotype (n = 31) was “unclassifiable.” The status of the remaining oocytes included germinal vesicle (GV) or germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) in 23 oocytes, and metaphase I (MI) in 22 oocytes. The results of oocyte response to IVM are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of oocytes collected and their developmental stage

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Total | 30s | 40s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35 | 44 | 41 | 41 | 38 | 42 | 42 | 35 | |||

| Oocytes (n) | 25 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 14 | 11 | 5 | 26 | 87 | 65 | 22 |

| GV, GVBD | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 23 | 14 | 9 |

| MI | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 22 | 17 | 5 |

| MII | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 0 |

| Unclassified | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 31 | 23 | 8 |

| Average | 10.9 | 21.7 | 4.4 |

Nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 and immunofluorescent detection of microtubules after IVM revealed that the spindle apparatus of oocytes was in various nuclear phases. We observed characteristic microtubule and chromatin formation in oocytes that reached MII after IVM, and that oocytes arrested before the MII stage after 48 h of IVM (Fig. 2). In addition, immunofluorescence staining revealed various malformations of the meiotic spindle in MII oocytes obtained from two patients (Fig. 3). There were oocytes showing chromosome misalignment and the loss of microtubule arrangement, which comprise the meiotic spindle.

Fig. 2.

Oocyte staging by DNA and microtubule assessment. Nuclear staining by Hoechst 33342 and immunofluorescence staining for microtubules after in vitro maturation (IVM) revealed the spindle apparatus of oocytes in various nuclear phases. Microtubules (green) and chromatin (blue) were observed. a An oocyte in the germinal vesicle (GV) stage. b An oocyte in metaphase I (MI). c An oocyte in MI telophase. d An oocyte that has completed metaphase II (MII)

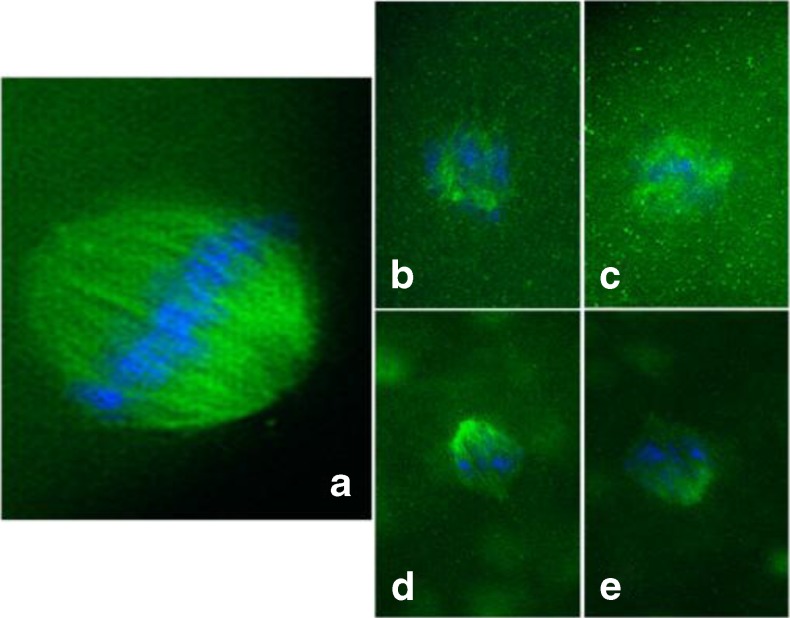

Fig. 3.

Assessment of meiotic spindle formation in oocytes after in vitro maturation (IVM). a–e Oocytes that have completed metaphase II (MII) after IVM. We used immunofluorescence staining to detect the meiotic spindle arrangements of oocytes in MII. Both normal (a) and deranged configurations (b–e) were observed

Discussion

Ethical issues constitute an obstacle to obtaining oocytes for human research. In this respect, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as standard treatment [5] for patients with uterine endometrial cancer represents an opportunity to avoid ethical problems associated with other sources of oocytes and obtain usable material for research without impacting the pathological diagnosis of the resected specimen. In humans, meiotic chromosome segregation errors, a major cause of aneuploidy, become dramatically more frequent as women age [4, 13]. A common aging-related problem during the maturation of human oocytes is poor sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I and meiosis II [14]. In aged mouse oocytes, there are lower levels of cohesion proteins such as Rec8 and shugoshins, which control meiotic chromosome segregation [2, 8]. On the other hand, there are no reports to date about changes in cohesion proteins associated with aging of human oocytes. One reason is that it is difficult to obtain human oocytes as research material. We were able to obtain oocytes in various stages from women of various ages in this study, which would be useful for such research. To our knowledge, this is the first report of immunofluorescent detection of microtubules after IVM of human oocytes from ovaries resected in patients with endometrial carcinoma. The number of oocytes collected from women in their 40s was clearly lower than that from women in their 30s in this study. In addition, we could not obtain oocytes in metaphase II from samples collected from women in their 40s. Wiser et al. reported IVM was a procedure best suited to patients younger than 40 years of age [15]. The number of oocytes and MII oocytes in women over 40 were significantly lower in their study of IVM in women of different ages. Unfortunately, we did not examine the patients’ hormone status: for example, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, anti-mullerian hormone levels during the perioperative period. In the future, to study the effects of IVM itself, a control group of oocytes developing in vivo can help identify contributing factors besides aging.

We conclude that materials for research on human ovarian aging can be obtained from ovaries removed from patients during surgery for endometrial cancer. We believe this is a useful and ethical method to advance research on aging-associated changes in oocyte function.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Y.T.) and the Uehara Memorial Fundation (Y.T.).

Footnotes

Capsule Surgically removed ovaries from patients with endometrial carcinoma represent a new source of material for human oocyte research.

References

- 1.Battaglia DE, Goodwin P, Klein NA, Soules MR. Influence of maternal age on meiotic spindle assembly in oocytes from naturally cycling women. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England) 1996;11(10):2217–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiang T, Duncan FE, Schindler K, Schultz RM, Lampson MA. Evidence that weakened centromere cohesion is a leading cause of age-related aneuploidy in oocytes. Curr Biol: CB. 2010;20(17):1522–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa H. The best approach to observe microtubule organization in oocyte cytoplasm production of oocyte wole mount samples by Buffer M Fixation. J Mamm Ova Res. 2009;26(4):232–3. doi: 10.1274/jmor.26.232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassold T, Hunt P. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(4):280–91. doi: 10.1038/35066065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphrey MM, Apte SM. The use of minimally invasive surgery for endometrial cancer. Cancer Control : J Moffitt Cancer Center. 2009;16(1):30–7. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krey LC, Grifo JA. Poor embryo quality: the answer lies (mostly) in the egg. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(3):466–8. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01778-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim AS, Tsakok MF. Age-related decline in fertility: a link to degenerative oocytes? Fertil Steril. 1997;68(2):265–71. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lister LM, Kouznetsova A, Hyslop LA, Kalleas D, Pace SL, Barel JC, et al. Age-related meiotic segregation errors in mammalian oocytes are preceded by depletion of cohesin and Sgo2. Curr Biol: CB. 2010;20(17):1511–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLaren A. Free-range eggs? Science (New York, NY) 2007;316(5823):339. doi: 10.1126/science.1142267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita J, Terada Y, Hosoi Y, Fujinami N, Sugimoto M, Nakamura S-I, et al. Microtubule organization during rabbit fertilization by intracytoplasmic sperm injection with and without sperm centrosome. Reprod Med Biol. 2005;4(2):169–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0578.2005.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revel A, Safran A, Benshushan A, Shushan A, Laufer N, Simon A. In vitro maturation and fertilization of oocytes from an intact ovary of a surgically treated patient with endometrial carcinoma: case report. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England) 2004;19(7):1608–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selesniemi K, Lee HJ, Muhlhauser A, Tilly JL. Prevention of maternal aging-associated oocyte aneuploidy and meiotic spindle defects in mice by dietary and genetic strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(30):12319–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018793108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanian VV, Bickel SE. Aging predisposes oocytes to meiotic nondisjunction when the cohesin subunit SMC1 is reduced. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(11):e1000263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogt E, Kirsch-Volders M, Parry J, Eichenlaub-Ritter U. Spindle formation, chromosome segregation and the spindle checkpoint in mammalian oocytes and susceptibility to meiotic error. Mutat Res. 2008;651(1–2):14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiser A, Son WY, Shalom-Paz E, Reinblatt SL, Tulandi T, Holzer H. How old is too old for in vitro maturation (IVM) treatment? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(2):381–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]