Abstract

Background

Existing information on consequences of the DSM-5 revision for diagnosis of alcohol use disorders (AUD) has gaps, including missing information critical to understanding implications of the revision for clinical practice.

Methods

Data from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions were used to compare AUD severity, alcohol consumption and treatment, sociodemographic and health characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity among individuals with DSM-IV abuse versus DSM-5 moderate AUD and DSM-IV dependence versus DSM-5 severe AUD. For each pair of disorders, we additionally compared three mutually exclusive groups: individuals positive solely for the DSM-IV disorder, those positive solely for the DSM-5 disorder and those positive for both.

Results

Whereas 80.5% of individuals positive for DSM-IV dependence were positive for DSM-5 severe AUD, only 58.0% of those positive for abuse were positive for moderate AUD. The profiles of individuals with DSM-IV dependence and DSM-5 severe AUD were almost identical. The only significant (p<.005) difference, more AUD criteria among the former, reflected the higher criterion threshold (≥4 vs. ≥3) for severe AUD relative to dependence. In contrast, the profiles of individuals with DSM-5 moderate AUD and DSM-IV abuse differed substantially. The former endorsed more AUD criteria, had higher rates of physiological dependence, were less likely to be White and male, had lower incomes, were less likely to have private and more likely to have public health insurance, and had higher levels of comorbid anxiety disorders than the latter.

Conclusions

Similarities between the profiles of DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD far outweigh differences; however, clinicians may face some changes with respect to appropriate screening and referral for cases at the milder end of the AUD severity spectrum, and the mechanisms through which these will be reimbursed may shift slightly from the private to public sector.

Keywords: DSM-5, AUD, treatment, severity, clinical profile

INTRODUCTION

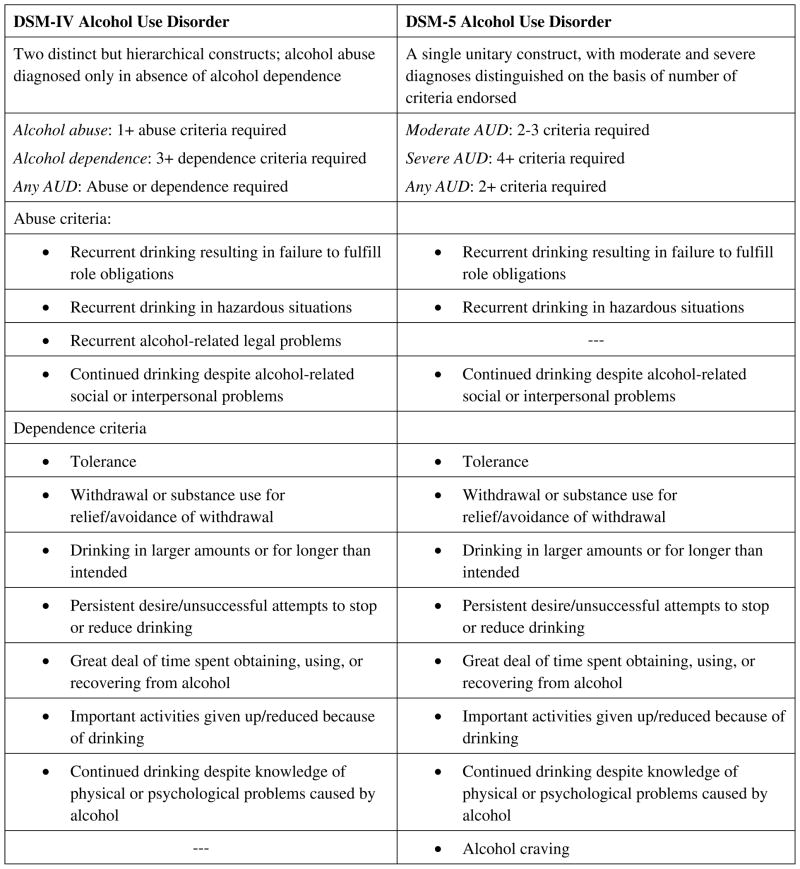

The proposed DSM-5 revision (http://www.dsm5.org) of the criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUD)represents a conceptual shift from the biaxial distinction between alcohol abuse and dependence to a unitary construct of AUD varying only in terms of severity. This shift was informed by studies supporting a single underlying latent AUD construct (Borges et al., 2010; Kahler and Strong, 2006: McBride et al., 2011; Saha et al., 2006; Smulewitz et al., 2010) and demonstrating that the DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) were interspersed in terms of severity (Harford et al., 2009; Ray et al., 2008; Saha et al., 2006), by calls for dimensional as well as categorical representations of AUD (Helzer et al., 2006), and by evidence that abuse did not necessarily precede the incidence of dependence (Grant et al., 2009; Vérgeset al., 2010). In the DSM-5 revision, the criterion of alcohol-related legal problems was dropped because of its low prevalence and poor psychometric properties (Saha et al., 2006), and a new craving criterion was added, consistent with its inclusion in the International Classification of Disease criteria for alcohol dependence (World Health Organization, 1992). Thus, the total number of AUD criteria remained at 11 (Figure 1). However, whereas DSM-IV abuse and dependence were based on discrete sets of diagnostic criteria (four for abuse and seven for dependence), all 11 criteria apply towards DSM-5 AUD (2–3 required for moderate AUD and ≥4 required for severe AUD). These changes resulted in cases of AUD lost, gained and shifted in severity under the DSM-5 revision. For example, individuals who were positive for DSM-IV abuse by virtue of having endorsed a single abuse criterion would no longer qualify for a diagnosis of AUD under the DSM-5 (unless they also endorsed at least one of the former dependence criteria). However, individuals endorsing just two of the former DSM-IV dependence criteria, formerly diagnostic or phans (Hasin and Paykin, 1998), would qualify for a diagnosis of DSM-5 moderate AUD.

Figure 1.

Classification of alcohol use disorder under the DSM-5 and proposed DSM-V criteria

Although the DSM-5 revision addressed concerns about individuals being inappropriately classified with an AUD solely for endorsing impaired driving (Agrawal et al., 2010; Babor and Caetano, 2008), it has been criticized on other grounds. The predominant criticisms were that the revision was overly reliant on statistical evaluations of the dimensionality and severity of AUD criteria based on insufficiently validated symptom item indicators, that it combined core characteristics of AUD with its consequences and that it did not do enough to create a diagnosis that would correspond to a need for treatment or provide guidance for clinicians (Babor, 2011; Poznyak et al., 2011; Room, 2011).

Two recent studies examined the impact of the DSM-5 proposed revision on the prevalence of AUD in the general population. In a study based on the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being, the past-year prevalence of DSM-IV abuse or dependence was considerably lower than that of DSM-5 AUD, 6.0% versus 9.7% (Mewton et al., 2011). Findings indicated that 56.2% of the DSM-IV abuse cases would be retained in DSM-5 moderate AUD and that 69.2% of the DSM-IV dependence cases would be retained in DSM-5 severe AUD. This study focused on the dimensionality of AUD, which was very similar under the DSM-IV and DSM-5, but it did not compare profiles of individuals with DSM-IV and DSM-5 disorders.

In a similar U.S. study based on Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), the overall rates of DSM-IV and DSM-5 past-year AUD were of similar magnitude, 9.7 and 10.8%(Agrawal et al., 2011). Thus, the rate of DSM-5 AUD was similar to that reported by Mewton et al., but the rate of DSM-IV AUD was higher. One reason offered by the authors as an explanation for this inconsistency is that the NESARC used impaired driving as an indicator of hazardous use, whereas the Australian study did not. The findings of the two studies were more congruent when impaired driving was excluded as an indicator of hazardous use in the U.S. study. Agrawal et al. (2011) reported that 58.0% of the DSM-IV abuse cases would be retained in DSM-5 moderate AUD and that 80.5% of the DSM-IV dependence cases would be retained in DSM-5 severe AUD. Compared to cases lost altogether under the DSM-5 revision (those positive for any DSM-IV AUD but no DSM-5 AUD), cases gained (positive for DSM-5 but not DSM-IV AUD) were younger, more likely to be female and non-Caucasian, less likely to have high incomes and more likely to be below the poverty level. In addition, cases gained were more likely to drink 5+/4+ (men/women) drinks on a weekly basis, reported larger usual drink quantities, endorsed more DSM-5 criteria, were more likely to have physiological dependence (tolerance or withdrawal), and had more lifetime psychiatric disorders than cases lost.

These studies provided an important first look at the implications of the DSM-5 revision for the prevalence of AUD and its clinical profile. However, neither study compared the characteristics of individuals with abuse relative to those with moderate AUD, nor of those with dependence relative to those with severe AUD. Moreover, neither examined the differences under the DSM-IV and DSM-5 in alcohol treatment utilization or potentially related factors such as type of health insurance coverage, usual source of medical care, medical conditions, and responsibility for alcohol-related injuries. These comparisons are important for addressing concerns that the DSM-5 revision is inadequately tied to clinical practice and need for treatment. Accordingly, the primary objectives of this study were 1) to compare and assess the statistical significance of differences in past-year prevalence for DSM-IV and DSM-5 abuse/moderate AUD and dependence/severe AUD in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults; and 2) to compare and statistically test differences in sociodemographic and health characteristics, psychiatric and other substance use comorbidity, alcohol consumption, AUD severity and treatment utilization for individuals meeting the DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnoses.

METHODS

Sample

This study uses data from the Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), the 3-year follow-up of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. The 2001–2002 Wave 1 sample contained 43,093 respondents 18 and older living in households and noninstitutional group quarters (response rate = 81.0%). At the 2004–2005 Wave 2 follow-up, 34,653 of the original respondents were reinterviewed (86.7% of those eligible for reinterview, cumulative response rate = 70.2%). Detailed information on the sample design and weighting is reported elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003a, 2007a, 2009) Informed consent was obtained after potential respondents were informed in writing about the nature of the survey, uses of the survey data, voluntary nature of their participation and confidentiality of identifiable survey information. The research protocol received full ethical review and approval. In this analysis, prevalence estimates of past-year DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD were based on the full Wave 2 sample (n=34,653). Clinical profiles of DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD were based on individuals who met the criteria for these disorders in the year immediately preceding the Wave 2 follow-up interval (n=108 to 1,734, see Analysis for details).

Measures

DSM-IV and DSM-5 alcohol use disorders

A diagnosis of past-year DSM-IV dependence required endorsement of ≥3 dependence criteria (Figure 1) in the year immediately preceding the Wave 2 interview, whereas a diagnosis of past-year DSM-IV abuse required anendorsement of at least one abuse criterion. The DSM-IV AUD diagnoses are highly reliable, e.g. kappa = .74 for past-year AUD (Grant et al., 2003b). To be positive for past-year DSM-5 moderate AUD, respondents had to endorse 2–3 of the 11 DSM-5 AUD criteria (Figure 1)during the year preceding the Wave 2 interview. Past-year DSM-5 severe AUD required endorsement of ≥4 criteria.

Past-year alcohol use, AUD severity and treatment

Number of AUD criteria refers to the number of criteria endorsed in the year preceding the Wave 2 interview, out of the 12 criteria used for either DSM-IV or DSM-5 AUD, i.e., including both legal problems and craving. Physiological dependence was defined as endorsing the criteria for tolerance and/or withdrawal. Volume of ethanol intake (Dawson, 2003) reflected the larger of the sum of four beverage-specific volumes or the volume for all types of alcoholic drinks combined. Frequency of drinking 5+ drinks in a single day was converted to days per year using midpoints of response categories. Both consumption measures demonstrated good to excellent test-retest reliability, with intraclass coefficients of .68 to .83 (Grant et al., 2003b). Alcohol treatment was broadly defined to include past-year utilization of inpatient or outpatient treatment from alcohol specialty or general medical sources, rehabilitation or detoxification programs, nonmedical sources such as family services agencies, clergy and employee assistance programs, and participation in 12-step programs.

Background characteristics

Background characteristics refer to the year preceding the Wave 2 interview unless otherwise noted. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, race/ethnicity, marital status (married/cohabiting vs. not), educational attainment (attended/completed college vs. not), employment, and family income <$20,000 vs. ≥$20,000. Other measures included health insurance coverage (private, public, and none), usual source of medical care (private doctor, HMO doctor, clinic/emergency department, and none), number of medical conditions based on 17 conditions (e.g., diabetes, liver cirrhosis, hypertension) for which respondents had to report confirmation by a health professional, and number of major life stressors from a list of 14 (Dawson et al., 2005). Psychological and physical functioning comprised the norm-based mental and physical component scales (NBMCS and NBPCS) of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey (SF-12v2) (Ware et al., 2002), rescaled to a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 in the U.S. general population. Higher scores indicate better functioning. Age at first drink excluded tastes or sips of someone else’s drink. First-degree familial alcoholism comprised respondent-reported alcohol problems in biological parents, full siblings and/or biological children.

Comorbidity

Past-year mood disorder (major depressive, bipolar I or II disorders, dysthymia or hypomania), anxiety disorder (panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social or specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder), nicotine dependence and drug use disorder (DUD) for any of 10 types of illicit drugs were measured in accordance with DSM-IV criteria, as was lifetime personality disorder (PD)(antisocial, paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, histrionic, narcissistic, avoidant, dependent or obsessive-compulsive). The derivation, fair to good reliability (kappa = .40 to .79) and validity of these diagnoses have been reported elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c; Pietrzak et al., 2011; Pulay et al., 2010; Ruan et al., 2008; Stinson et al., 2005).

Analysis

Differences in the prevalence rates of past-year DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD diagnoses were tested in the full sample, using the SAS McNemar test statistic for differences of proportions in paired data, (http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/procstat/63104/HTML/default/viewer.htm#procstat_freq_sect008.htm). This statistic accounts for the inherent positive correlation of each individual’s DSM-IV and corresponding DSM-5 diagnoses resulting from the many common symptom item indicators shared by the two sets of criteria. All other statistical analyses employed SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, 2008) to adjust variance estimates for the complex, multi-stage sample design of the NESARC.

We employed t-tests of means and proportions to compare characteristics of all individuals in three mutually exclusive groups: 1) individuals positive solely for the DSM-IV disorder in question, 2) those positive solely for the DSM-5 disorder and 3) those positive for both. For comparing overall differences in clinical profiles, the substantial diagnostic overlap (cases positive for DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD)precluded using statistical tests designed for independent samples. Statistical procedures for testing differences in overlapping samples (Thompson, 1995) are intended to compare two different variables, e.g., income at time 1 and time 2, within an overlapping sample of the type where portions of the respondents rotate in and out in any given year. These procedures are not appropriate for testing differences in a single variable (e.g., age) across overlapping groups. Accordingly, we used a partial split sample design to create the largest possible mutually exclusive samples of individuals with DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnoses. Using abuse/moderate AUD as an example, the sample for DSM-IV abuse comprised all respondents who were positive solely for abuse (group 1 above) and half of those positive for both abuse and moderate AUD (group 3), the latter upweighted by a constant adjustment factor of ≈2 (the inverse of the split group 3 sample size divided by the full group 3 sample size) to be representative of its full unsplit prevalence. The sample for DSM-5 moderate AUD consisted of all respondents who were positive solely for moderate AUD (group 2) and the remaining half of those positive for both abuse and moderate AUD (group 3), the latter again upweighted to its full prevalence.(Without upweighting, the profiles of DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD would have overrepresented individuals positive solely for the disorder in question, all of whom contributed to the profile compared with only half of those positive for both disorders.) The same approach was used to create mutually exclusive samples for DSM-IV dependence and DSM-5 severe AUD. In order to create the two random half samples required for this approach, we applied even case identification numbers towards the DSM-5 diagnoses and odd case identification numbers towards the DSM-IV diagnoses. Case identification numbers were randomly generated when the Wave 1 and Wave 2 NESARC data sets were merged. We were then able to use t-tests of differences in independent samples to compare the clinical profiles of the DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnoses. In order to account for multiple comparisons, we applied a p-value of <.005 for citing differences as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Prevalence and concordance of DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD

As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of past-year DSM-5 moderate AUD was higher than the prevalence of past-year DSM-IV abuse, 6.9% versus 5.3% (McNemar’stest statistic = 153.3, df=1, p<.0001). Of individuals positive for any DSM-IV abuse, 42.0% did not satisfy the criteria for a DSM-5 moderate AUD. These were primarily composed (84.8%) of individuals who had satisfied a single DSM-IV abuse criterion, almost always hazardous use (data not shown). An additional 0.8% had satisfied two DSM-IV abuse symptoms, one of which was legal problems, which did not count towards a DSM-5 diagnosis, and 14.4% were individuals with two or fewer DSM-IV dependence whose combination of abuse and dependence symptoms was sufficiently large (≥4) to for a diagnosis of severe AUD.

Table 1.

Prevalence of DSM-IV and DSM-5 past-year alcohol use disorders (AUD)

| Disorder | Past-year prevalence of disorder | Among those prevalent for past-year disorder, percentage who were positive for: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV but not corresponding DSM-5 diagnosis | DSM-5 but not corresponding DSM-IV diagnosis | DSM-IV and corresponding DSM-5 diagnosis | ||

| Moderate AUD: | ||||

| DSM-IV alcohol abuse | 5.3 (0.2) | 42.0 (1.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | 58.0 (1.4) |

| DSM-5 moderate AUD | 6.9 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 55.7 (1.4) | 44.3 (1.4) |

| Severe AUD: | ||||

| DSM-IV alcohol dependence | 4.4 (0.2) | 19.5 (1.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 80.5 (1.3) |

| DSM-5 severe AUD | 3.9 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 8.3 (0.9) | 91.7 (0.9) |

Note: Figures in parentheses are standard errors of estimates.

Among individuals positive for a DSM-5 moderate AUD, 55.7% had not satisfied the DSM-IV criteria for abuse. The majority, 71.7%, comprised former diagnostic orphans who had been positive for two DSM-IV dependence criteria but no abuse criteria (data not shown). An additional 6.2% had been positive for just one DSM-IV dependence criterion but were also positive for craving, bringing their total DSM-5 criterion count to two. The remainder, 22.1%, had been positive for three DSM-IV dependence criteria and remained positive for three DSM-5 criteria. These individuals were downgraded from the more severe DSM-IV diagnostic category of dependence into the less severe DSM-5 category of moderate AUD.

The rate of past-year DSM-5 severe AUD was slightly lower than that for past-year DSM-IV dependence, 3.9% versus 4.4% (McNemar’s test statistic = 84.7, df=1, p<.0001). Of individuals positive for dependence, 19.5% were not positive for severe AUD. Almost all (98.3%) of these cases consisted of individuals with three positive dependence and no abuse criteria, although a small proportion (1.7%) had three positive dependence criteria coupled with legal problems, an abuse criterion that did not count towards DSM-5 AUD (data not shown). The dependence criteria most often endorsed by these cases were drinking in larger quantities or for longer than intended (81.8%) and persistent desire/unsuccessful attempts to stop or reduce drinking (71.6%). All of these cases were downgraded into the less severe category of moderate AUD; none were lost altogether in terms of a DSM-5 diagnosis. Of cases positive for DSM-5 severe AUD, 8.3% were not positive for DSM-IV dependence. These consisted of individuals with one or two dependence criteria, whose total number of DSM-5 criteria was ≥4 as a result of positive abuse criteria and/or craving. More than half (57.1%) of these cases would have fallen into the category of moderate AUD without the addition of craving as a criterion under the DSM-5.

Comparison of DSM-IV abuse and DSM-5 moderate AUD

As indicated in Table 2, individuals positive solely for DSM-5 moderate AUD (column 2) had more positive AUD criteria and a higher prevalence of physiological dependence than those positive solely for DSM-IV abuse(column 1). In addition, those positive solely for moderate AUD were younger, less likely to be White but more likely to be Black or Hispanic, less likely to be male and married, more likely to have low incomes, less likely to have private but more likely to have public health insurance coverage, and less likely to report a private physician but more likely to cite clinics or emergency departments as their main source of medical care than those positive solely for abuse. They also had more major life stressors, lower scores for psychological functioning, and higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity and nicotine dependence but lower rates of comorbid DUD. Individuals who were positive for both abuse and moderate AUD (column 3) differed in numerous ways from those with abuse only or moderate AUD only. Their values for physical health and comorbidity measures tended to lie between those of the latter two groups, whereas their values for AUD measures tended to indicate greater severity than those for either of the other two groups.

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of individuals with past-year DSM-IV alcohol abuse and/or DSM-5 moderate alcohol use disorder (AUD)

| Characteristic | Mutually exclusive groups: full sample | Partially-split sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals positive for abuse/moderate AUD under: | Individuals positive for: | ||||

| DSM-IV only (n = 716) (1) | DSM-5 only (n = 1,258) (2) | DSM-IV and 5 (n = 993) (3) | DSM-IV abusea(n = 1,233) (4) | DSM-5 moderate AUDb (n = 1,734) (5) | |

| Past-year alcohol use, AUD severity, treatment | |||||

| Mean # AUD criteria (range 1-12) | 1.5 (0.0) | 2.3 (0.0)c | 2.5 (0.0)c,d | 2.0 (0.0) | 2.4 (0.0)e |

| % Physiological dependence | 7.4 (1.1) | 63.2 (1.7)c | 37.3 (1.6)c,d | 25.6 (1.4) | 51.1 (1.7)e |

| Mean ADV ethanol intake | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1)c,d | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) |

| Mean days/yr. drank 5+ drinks | 39.7 (3.0) | 45.0 (3.2) | 60.5 (3.5)c,d | 49.5 (2.7) | 53.7 (3.1) |

| % Alcohol-related injury | 4.7 (1.0) | 2.6 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.7) |

| % Alcohol treatment | 2.0 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.3) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.5) |

| Background characteristics: | |||||

| Mean age | 42.1 (0.7) | 38.1 (0.5)c | 38.3 (0.5)c | 39.9 (0.5) | 38.2 (0.4) |

| % White | 81.2 (1.9) | 64.2 (2.2)c | 80.2 (1.5)d | 79.9 (1.6) | 71.8 (1.7)e |

| % Black | 8.0 (1.1) | 14.6 (1.4)c | 7.8 (1.0)d | 8.1 (1.0) | 11.5 (1.0) |

| % Native American | 1.5 (0.5) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.5) |

| % Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.4 (0.5) | 2.9 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.6) |

| % Hispanic | 7.8 (1.3) | 15.7 (1.8)c | 7.3 (1.1)d | 7.7 (1.1) | 11.8 (1.4) |

| % Male | 72.8 (1.8) | 59.6 (1.6)c | 74.6 (1.4)d | 75.2 (1.4) | 65.1 (1.2)e |

| % Married | 59.8 (2.2) | 51.0 (1.9)c | 51.7 (1.9) | 55.3 (1.9) | 51.1 (1.5) |

| % Attended college | 69.7 (2.2) | 61.9 (2.0) | 63.1 (1.9) | 66.4 (1.6) | 62.0 (1.7) |

| % Employed | 90.0 (1.2) | 87.0 (1.2) | 92.5 (1.0)d | 91.6 (0.9) | 89.3 (1.0) |

| % Income <$20,000 | 10.6 (1.3) | 22.3 (1.5)c | 13.3 (1.3)d | 11.9 (1.1) | 18.5 (1.3)e |

| % Private health insurance | 84.6 (1.5) | 71.1 (1.8)c | 78.2 (1.6)c,d | 81.3 (1.5) | 73.9 (1.5)e |

| % Public health insurance | 4.3 (0.8) | 10.9 (1.0)c | 5.7 (0.9)d | 4.6 (0.7) | 9.0 (0.8)e |

| % No health insurance | 11.1 (1.4) | 17.9 (1.6)c | 16.1 (1.3) | 14.1 (1.3) | 17.1 (1.2) |

| % Usual care from private MD | 63.1 (2.1) | 54.4 (1.9)c | 56.0 (1.9) | 59.5 (1.8) | 54.7 (1.7) |

| % Usual care from HMO | 15.1 (1.6) | 16.5 (1.4) | 17.5 (1.6) | 16.1 (1.3) | 17.3 (1.2) |

| % Usual care from clinic/ED/etc. | 11.7 (1.4) | 18.6 (1.4)c | 14.6 (1.4) | 13.4 (1.2) | 16.8 (1.2) |

| % No usual source of care | 10.1 (1.2) | 10.5 (1.1) | 12.0 (1.2) | 11.0 (1.1) | 11.3 (1.0) |

| Mean # medical conditions | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) |

| Mean # major life stressors | 1.9 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1)c | 2.2 (0.1)c | 2.1 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) |

| SF12 NBMCSf | 52.3 (0.3) | 49.4 (0.3)c | 51.0 (0.3)c,d | 51.1 (0.3) | 50.4 (0.3) |

| SF12 NBPCSf | 53.6 (0.3) | 52.3 (0.3) | 53.6 (0.3) | 53.8 (0.3) | 52.7 (0.3) |

| Mean age at first drink | 18.2 (0.2) | 18.4 (0.1) | 17.9 (0.1) | 18.0 (0.1) | 18.2 (0.1) |

| % 1st degree familial AUD | 36.3 (2.2) | 37.4 (1.9) | 37.6 (2.0) | 35.7 (1.6) | 38.6 (1.6) |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||

| % Any past-year mood disorder | 8.4 (1.3) | 16.1 (1.3)c | 11.8 (1.1) | 10.4 (1.1) | 14.1 (1.0) |

| % Any past-year anxiety disorder | 14.9 (1.5) | 24.7 (1.6)c | 16.4 (1.3)d | 15.1 (1.1) | 21.6 (1.3)e |

| % Any personality disorder | 26.3 (1.9) | 35.8 (1.6)c | 29.4 (1.9) | 28.6 (1.6) | 32.5 (1.5) |

| % Past-year nicotine dependence | 18.4 (1.8) | 26.3 (1.6)c | 26.6 (1.7)c | 24.4 (1.6) | 25.3 (1.4) |

| % Any past-year drug use disorder | 6.2 (1.0) | 2.9 (0.6)c | 9.4 (1.1)d | 7.1 (0.9) | 6.6 (0.9) |

Note: Figures in parentheses are standard errors of estimates; standard errors of 0.0 denote values <0.05)

Based on all cases in column 1 and a random half sample of cases in column 3

Based on all cases in column 2 and a random half sample of cases in column 3

Estimate is significantly different (p<.005) from that for individuals with DSM-IV diagnosis only (col. 1)

Estimate is significantly different (p<.005) from that for individuals with DSM-5 diagnosis only (col. 2)

Estimate is significantly different (p<.005) from that for all individuals with DSM-IV diagnosis (col. 4)

NBMCS = norm-based mental component score; NBPCS = norm-based physical component score

Many of the differences between columns 1 and 2 were reflected in the overall profiles of DSM-IV abuse and DSM-5 moderate AUD (columns 4 and 5). Individuals with moderate AUD endorsed more AUD criteria, were more likely to have physiological dependence, were less likely to be White, male, and privately insured, were more likely to have low incomes and public health insurance and had higher rates of anxiety disorder than those with abuse.

Comparison of DSM-IV dependence and DSM-5 severe AUD

As shown in Table 3, individuals positive solely for DSM-5 dependence(column 2) endorsed more AUD criteria despite lower rates of physiological dependence, were more likely to be male, to have private health insurance coverage and to have a comorbid drug use disorder, and reported fewer medical conditions than the those positive solely for DSM-IV dependence (column 1). Individuals positive for both DSM-IV dependence and DSM-5 severe AUD reported more AUD criteria, had higher rates of alcohol treatment and had lower levels of psychological functioning than those meeting only a single diagnosis. Compared to individuals positive solely for dependence, they were heavier drinkers, were more likely to have been responsible for an alcohol-related injury and had more life stressors and higher rates of DUD. Compared to individuals positive solely for severe AUD, they were more likely to endorse physiological dependence, had lower rates of private but higher rates of public health insurance coverage, and reported more medical conditions. The overall clinical profiles of dependence (column 4) and severe AUD(column 5) were very similar, the only significant difference being that individuals with severe AUD endorsed more AUD criteria.

Table 3.

Selected characteristics of individuals with past-year DSM-IV alcohol dependence and/or DSM-5 severe alcohol use disorder (AUD)

| Characteristic | Mutually exclusive groups | Partially-split sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals positive for dependence/severe AUD under: | Individuals positive for: | ||||

| DSM-IV only (n = 269) (1) | DSM-5 only (n = 108) (2) | DSM-IV and 5 (n = 1,164) (3) | DSM-IV dependencea (n = 844) (4) | DSM-5 severe AUDb (n = 697) (5) | |

| Past-year alcohol use, AUD severity, treatment | |||||

| Mean # AUD criteria (range 1–12) | 3.0 (0.0) | 4.2 (0.0)c | 6.0 (0.1)c,d | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.1)e |

| % Physiological dependence | 84.7 (2.5) | 51.2 (6.0)c | 89.1 (1.1)d | 86.0 (1.5) | 88.3 (1.3) |

| Mean ADV ethanol intake | 1.3 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.1)c | 2.7 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) |

| Mean days/yr. drank 5+ drinks | 58.3 (8.6) | 96.5 (11.6) | 116.4 (4.1)c | 106.3 (5.2) | 113.5 (5.5) |

| % Alcohol-related injury | 5.0 (2.0) | 18.5 (5.3) | 15.7 (1.3)c | 12.0 (1.5) | 17.6 (1.8) |

| % Alcohol treatment | 2.7 (1.0) | 6.2 (2.7) | 15.6 (1.4)c,d | 14.8 (1.8) | 13.0 (1.6) |

| Background characteristics: | |||||

| Mean age | 36.9 (1.0) | 34.6 (1.2) | 36.6 (0.4) | 37.0 (0.6) | 36.0 (0.6) |

| % White | 63.2 (3.9) | 73.1 (4.7) | 68.5 (2.5) | 69.0 (2.4) | 67.3 (2.9) |

| % Black | 17.9 (3.1) | 11.8 (3.3) | 11.2 (1.2) | 11.8 (1.2) | 12.2 (1.5) |

| % Native American | 1.3 (0.6) | 2.0 (1.4) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.0) |

| % Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.9 (0.9) | 5.4 (2.6) | 2.9 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.0) | 3.2 (1.1) |

| % Hispanic | 15.6 (3.3) | 7.8 (2.4) | 13.7 (1.9) | 13.5 (1.8) | 13.7 (2.4) |

| % Male | 63.9 (3.5) | 79.8 (4.3)c | 69.7 (1.8) | 68.1 (2.0) | 71.1 (2.3) |

| % Married | 47.5 (3.9) | 47.2 (5.6) | 41.7 (1.7) | 42.2 (2.2) | 42.8 (2.2) |

| % Attended college | 60.6 (3.9) | 59.5 (5.3) | 57.3 (1.9) | 59.1 (2.3) | 56.2 (2.2) |

| % Employed | 87.1 (2.6) | 90.5 (2.8) | 87.9 (1.2) | 88.6 (1.3) | 87.3 (1.6) |

| % Income <$20,000 | 27.6 (3.4) | 19.2 (4.1) | 26.8 (1.7) | 26.6 (2.1) | 26.6 (2.2) |

| % Private health insurance | 64.0 (3.8) | 79.6 (4.5)c | 66.0 (1.7)d | 66.1 (2.1) | 66.5 (2.1) |

| % Public health insurance | 9.6 (2.2) | 3.6 (1.8) | 11.1 (1.1)d | 9.6 (1.2) | 11.8 (1.4) |

| % No health insurance | 26.3 (3.9) | 16.8 (4.3) | 22.9 (1.7) | 24.3 (2.1) | 21.7 (2.1) |

| % Usual care from private MD | 50.9 (3.7) | 49.7 (5.1) | 50.5 (1.8) | 50.7 (2.1) | 50.2 (2.3) |

| % Usual care from HMO | 19.1 (2.9) | 12.5 (3.7) | 14.4 (1.2) | 15.6 (1.4) | 13.9 (1.5) |

| % Usual care from clinic/ED/etc. | 16.9 (2.7) | 23.7 (4.9) | 21.9 (1.4) | 20.0 (1.6) | 23.0 (2.0) |

| % No usual source of care | 13.1 (2.9) | 14.1 (3.4) | 13.3 (1.2) | 13.8 (1.5) | 12.8 (1.7) |

| Mean # medical conditions | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1)c | 0.8 (0.1)d | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) |

| Mean # major life stressors | 2.6 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | 3.2 (0.1)c | 3.1 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.1) |

| SF12 NBMCSf | 48.3 (0.9) | 48.9 (1.0) | 45.5 (0.4)c,d | 46.0 (0.5) | 45.9 (0.5) |

| SF12 NBPCSf | 51.6 (0.7) | 53.9 (0.8) | 51.7 (0.4) | 51.6 (0.5) | 51.8 (0.5) |

| Mean age at first drink | 18.7 (0.3) | 17.6 (0.4) | 17.7 (0.2) | 17.7 (0.2) | 17.9 (0.3) |

| % 1st degree familial AUD | 39.8 (3.6) | 52.2 (5.5) | 48.6 (1.9) | 46.0 (2.2) | 49.8 (2.3) |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||

| % Any past-year mood disorder | 22.0 (3.1) | 16.1 (4.1) | 28.8 (1.6)d | 29.0 (1.9) | 26.2 (2.1) |

| % Any past-year anxiety disorder | 28.5 (3.7) | 25.9 (4.6) | 35.4 (1.7) | 34.9 (2.1) | 33.6 (2.1) |

| % Any personality disorder | 41.1 (3.7) | 41.5 (5.3) | 51.2 (1.8) | 50.8 (2.2) | 48.8 (2.4) |

| % Past-year nicotine dependence | 33.0 (3.7) | 40.3 (5.8) | 41.8 (1.9) | 41.7 (2.2) | 40.0 (2.5) |

| % Any past-year drug use disorder | 2.8 (1.4) | 14.7 (3.6)c | 13.4 (1.2)c | 11.0 (1.4) | 13.7 (1.6) |

Note: Figures in parentheses are standard errors of estimates; standard errors of 0.0 denote values <0.05)

Based on all cases in column 1 and a random half sample of cases in column 3

Based on all cases in column 2 and a random half sample of cases in column 3

Estimate is significantly different (p<.005) from that for individuals with DSM-IV diagnosis only (col. 1)

Estimate is significantly different (p<.005) from that for individuals with DSM-5 diagnosis only (col. 2)

Estimate is significantly different (p<.005) from that for all individuals with DSM-IV diagnosis (col. 4)

NBMCS = norm-based mental component score; NBPCS = norm-based physical component score

DISCUSSION

In a general population sample of U.S adults, the proposed DSM-5 cutpoint of ≥4 positive criteria for severe AUD yielded a diagnosis that closely corresponded to DSM-IV dependence in terms of alcohol consumption, treatment utilization, sociodemographic profile, psychosocial impairment and comorbidity. The only significant difference between the two profiles, the higher mean number of AUD criteria endorsed by individuals positive for severe AUD, reflected the higher number of positive criteria required for the DSM-5 diagnosis. A marginally higher proportion of individuals reporting alcohol-related injuries under DSM-5 severe AUD (p = .017) resulted from abuse criteria counting towards severe AUD but not dependence. Among individuals positive for severe AUD but not dependence, more than 80% of those reporting alcohol-related injuries endorsed the criterion of hazardous use and had been classified with abuse rather than dependence under the DSM-IV.

These slight differences in the clinical profiles of dependence and severe AUD suggest no need for major change in adapting existing clinical practices to suit the needs of individuals with DSM-5 severe AUD, with one possible exception. Some of the individuals who screen positive for AUD in primary care or emergency department settings may be classified with a more severe disorder under the DSM-5(severe AUD) than under the DSM-IV (abuse). Thus, some of the individuals who likely would have received a brief intervention under the DSM-IV may now be considered candidates for more intensive treatment modalities. An important area for future research will be to determine whether these individuals respond to recommendations for treatment and whether it offers any benefits beyond those conferred by brief interventions, which have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing harmful drinking practices and associated costs (Fleming, 2000; Havard et al., 2011; Solberg, 2008).

In contrast to the high level of concordance between DSM-IV alcohol dependence and DSM-5 severe AUD, (80.5%) there was a considerably lower level of concordance between DSM-IV alcohol abuse and DSM-5 moderate AUD (58%). Discrepancies reflect both the criteria upon which the two disorders are based – which include core characteristics of AUD such as tolerance, withdrawal, craving and impaired control for moderate AUD but not abuse – and the requirement of two positive criteria for moderate AUD compared to one positive criterion for abuse. When individuals with DSM-5 moderate AUD were compared to those with DSM-IV abuse, there were striking reductions in the proportions of Whites and males and a striking increase in the proportion of low-income individuals, reflecting gender, race/ethnic and income disparities (Harford et al., 2009; Kahler and Strong, 2006; Keyes and Hasin, 2008; Saha et al., 2006) in the endorsement of hazardous use, which was sufficient in itself to establish a diagnosis of DSM-IV abuse but not DSM-5 moderate AUD. These findings closely mirrored those of Agrawal et al. (2011), reflecting the fact that all the cases lost for overall AUD under the DSM-5 came from the DSM-IV category of abuse. The higher proportions of women and race/ethnic minorities in the category of moderate AUD indicate a need to examine screening and treatment approaches formerly targeted at DSM-IV abuse for their appropriateness to a more diverse audience. In addition, the higher rates of anxiety disorder, physiological dependence and craving within DSM-5 moderate AUD relative to abuse suggest that the revised disorder would derive greater benefit from screening for dual diagnoses and may be more amenable to medication for all eviating craving and withdrawal symptoms. Finally, the lower proportion of cases with private health insurance coverage may have some ramifications for reimbursement; however, rates of treatment for those with either abuse or moderate AUD are so low that any shift in coverage would likely have a minimal impact.

One of the concerns with the DSM-5 revision has been whether individuals excluded from a diagnosis but formerly positive for an AUD, i.e., those positive for a single abuse criterion (usually hazardous use), will be adversely affected by no longer having a diagnosable condition for which the costs of treatment or brief intervention can be reimbursed. Although the prior study by Agrawal et al. (2011) presented a profile of this group of individuals, it did not examine treatment utilization. Whereas the present analysis provided a profile of cases that were positive for abuse but not moderate AUD, not all of the individuals in this category were excluded from a DSM-5 diagnosis; a small proportion were upgraded into the category of DSM-5 severe AUD. In post-hoc analyses of treatment utilization among individuals who went from positive to negative for any AUD under the DSM-5 (data not shown), only 1.3% had received help for alcohol problems in the past year, and the majority of these had sought help solely from nonmedical sources (e.g., 12-step programs, etc.). Thus, it would appear that few individuals will miss out on treatment that they otherwise would have received because of the DSM-5 exclusion of cases with a single abuse criterion.

In addition to having implications for clinicians, the results of this study have relevance for psychometricians. As noted previously, individuals who were positive solely for DSM-5 severe AUD had lower levels of physiological dependence, despite otherwise greater severity of AUD, than those positive solely for DSM-IV dependence. When this counter intuitive finding was explored in post-hoc analyses, the difference reflected less frequent endorsement among cases gained of sleep problems and vomiting, the mildest and most commonly endorsed withdrawal symptoms(Dawson et al., 2010; Kahler and Strong, 2006). Although these differences were marginally significant at the individual symptom level (p = .048 and .050), they resulted in a highly significant difference in the overall prevalence of physiological dependence (p <.001) for cases lost and gained. This suggests a psychometrically undesirable property of the withdrawal criterion, i.e., a tendency to be inversely related to other indicators of AUD severity when defined solely in terms of its mildest symptoms. This observation is consistent with findings reported elsewhere (Harford et al., 2009; Kahler and Strong, 2006) that the withdrawal criterion had a low discrimination score and wide dispersion relative to AUD severity, particularly among young age groups. Kahler and Strong (2006) also reported that both sleep problems and vomiting exhibited differential item functioning with respect to sex, reflecting greater severity among women than men, reinforcing the negative psychometric properties of these symptoms as sole indicators of withdrawal.

This study was limited by the fact that DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD were classified in largely overlapping rather than independent populations. As a result, comparisons of the clinical profiles of the disorders required partially split sample analyses that reduced the statistical power to discern differences in the profiles. Moreover, many highly relevant aspects of clinical course could not be addressed in this study. For example, questions on age at onset of AUD in the NESARC were asked with respect to the symptoms that defined DSM-IV AUD and could not be extrapolated to the corresponding DSM-5 AUD. Similarly, the questions that as certained chronological clustering of symptoms, necessary to establish a diagnosis for disorders prevalent in first two years of the follow-up interval, could not be extrapolated to the DSM-5 disorders. Because we were unable to create valid measures of DSM-5 AUD for the earlier time period, we were unable to compare the course of AUD (i.e., chronicity, remission, progression to more severe AUD) under the DSM-IV and DSM-5.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrated, in a large, nationally representative sample, important aspects of the clinical characteristics of AUD for two versions of the DSM. On the whole, the similarities in profiles of DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUD far outweighed the differences. However, clinicians may face some changes with respect to appropriate screening and referral for cases at the milder end of the AUD severity spectrum, and in terms of the extent to which these will be reimbursed. That is, the implications of the revision appear to be far more serious for screening and brief intervention than for intensive alcohol treatment.

Acknowledgments

The study on which this paper is based, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), is sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies or the U.S. government.

References

- Agrawal A, Bucholz KK, Lynskey MT. DSM-IV alcohol abuse due to hazardous use: a less severe form of abuse? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:857–863. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Heath AC, Lynskey MT. DSM-IV to DSM-5: the impact of proposed revisions on diagnosis of alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2011;106:1935–1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Caetano R. The trouble with alcohol abuse: what are we trying to measure, diagnose, count and prevent? Addiction. 2008;103:1057–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF. Substance, not semantics, is the issue: Comments on the proposed addiction criteria for DSM-V. Addiction. 2011;106:870–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Herpitel CJ, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Rubio-Stpiec M. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-national perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. There is potential for cultural and social bias in DSM-V. Addiction. 2011;106:895–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Ruan WJ. The association between stress and drinking: modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:453–460. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Saha TD, Grant BF. A multidimensional assessment of the validity and utility of alcohol use disorder severity as determined by item response theory models. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL. Benefit-cost analysis of brief physician advice with problem drinkers in primary care settings. Med Care. 2000;38:7–18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Kay W, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV(AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of dependence and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004a;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004b;61:361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004c;61:1107–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance abuse, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molec Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Yi HY, Faden VB, Chen CM. The dimensionality of DSM-IV alcohol use disorders among adolescent and adult drinkers and symptom patterns by age, gender and race/ethnicity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:868–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Beseler CL. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol abuse, dependence and binge drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: diagnostic ‘or phans’ in a community sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havard A, Shakeshaft AP, Conigrave KM, Doran CM. Randomized controlled trial of mailed personalized feedback for problem drinkers in the emergency department: the short term impact. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01632.x. E-pub a head of print, October 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, van den Brink W, Guth SE. Should there be both categorical and dimensional criteria for the substance use disorders in DSM-V? Addiction. 2006;101:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR. A Rasch model analysis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Socio-economic status and problem alcohol use: the positive relationship between income and the DSM-IV alcohol abuse diagnosis. Addiction. 2008;103:1120–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride O, Teeson M, Baillie A, Slade T. Assessing the dimensionality of lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and a quantity-frequency measure alcohol use criterion in the Australian population: a factor mixture modeling approach. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:333–341. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewton L, Slade T, McBride O, Grove R, Teesson M. An evaluation of the proposed DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria using Australian national data. Addiction. 2011;106:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznyak V, Reed GM, Clark N. Applying an international perspective to proposed changes for DSM-V. Addiction. 2011;106:868–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Grant BF. The relationship of DSM-IV personality disorders to nicotine dependence: results from a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LL, Kahler CW, Young D, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. The factor structure and severity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in psychiatric outpatients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:496–299. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 10.0. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Room R. Substance use disorders – a conceptual and terminological muddle. Addiction. 2011;106:879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV(AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou PS, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes K, Beseler C, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Spivak B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders: results from Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PC. A hybrid paired and unpaired analysis for the comparison of proportions. Statistics in Med. 1995;14:1463–1470. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vérges A, Steinley D, Trull TJ, Sher K. It’s the algorithm! Why differential rates of chronicity and comorbidity are not evidence for the validity of the abuse-dependence distinction. JAb norm Psychol. 2010;119:650–661. doi: 10.1037/a0020116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting Version 1) Quality Metric; Lincoln, RI: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1992. The ICD10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. [Google Scholar]