Abstract

Introduction. Depression is one of the four major diseases in the world and is the most common cause of disability from diseases. The aim of this study is to estimate the prevalence of depression among Iranian university students using meta-analysis method. Materials and Methods. Keyword depression was searched in electronic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, MAGIran, Medlib, and SID. Data was analyzed using meta-analysis (random-effects model). Heterogeneity of studies was assessed using the I 2 index. Data was analyzed using STATA software Ver.10. Results. In 35 studies conducted in Iran from 1995 to 2012 with sample size of 9743, prevalence of depression in the university students was estimated to be 33% (95% CI: 32–34). The prevalence of depression among boys was estimated to be 28% (95% CI: 26–30), among girls 23% (95% CI: 22–24), single students 39% (95% CI: 37–41), and married students 20% (95% CI: 17–24). Metaregression model showed that the trend of depression among Iranian students was flat. Conclusions. On the whole, depression is common in university students with no preponderance between males and females and in single students is higher than married ones.

1. Introduction

Depression among university students is extremely prevalent and widespread problem across the country [1–3]. University students are a special group of people that are enduring a critical transitory period in which they are going from adolescence to adulthood and can be one of the most stressful times in a person's life. Trying to fit in, maintain good grades, plan for the future, and be away from home often causes anxiety for a lot of students [4]. As a reaction to this stress, some students get depressed. They find that they cannot get themselves together. They may cry all of the time, skip classes, or isolate themselves without realizing they are depressed. Previous studies reported that depression in university students is noted around the world [5–7] and the prevalence seems to be increasing [8].

The average age of onset is also on the decline, making depression a particularly salient problem area for university student populations [8]. Over two-thirds of young people do not talk about or seek help for mental health problems [9].

In Iran, preliminary studies on emotional distress have emerged in recent years including depression in Iranian university. Within the abovementioned background, the aim of this study is to estimate the prevalence of depression among university students using meta-analysis method.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Literature Search

Our search strategy, selection of publications, and the reporting of results for the review will be conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [10]. Literatures on the depression among student were acquired through searching Scientific Information Databases (SID), Global Medical Article Limberly (Medlib), Iranian Biomedical Journal (Iran Medex), Iranian Journal Database (Magiran), and international databases including PubMed/Medline, Scopus and ISI Web of Knowledge. The search strategy was limited to the Persian and/or English language and articles published up until February 2012 were considered. All publications with medical subject headings (MeSh) and keywords in title, abstract, and text for words including student depression were investigated. Iranian scientific databases were searched only using the keyword “student depression,” as these databases do not distinguish synonyms from each other and do not allow sensitive search operation using linking terms such as “AND,” “OR” or “NOT.” Consequently, this single keyword search was the most practical option.

2.2. Selection and Quality Assessment of Articles

All identified papers were critically appraised independently by two reviewers. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. Appraisal was guided by a checklist assessing clarity of aims and research questions. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies in the mentioned databases with full text, despite the language of original text; (2) having a standardized assessment of depression (either self-report or observer-rated). Exclusion criteria were (1) studies upon student overlapping time intervals of sample collection from the same origin; (2) low-quality design (STROBE checklist score's below 7.75 [11]); (3) inadequate reporting of results.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a standardized and prepiloted data extraction form. Data extraction will be undertaken by the first reviewer, and checked by a second reviewer although the process will be discussed and piloted by both reviewers. All identified papers will be critically appraised independently by both reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Appraisal will be guided by a checklist assessing clarity of aims and research questions. Information was extracted from each included study (including author, title, year and setting of study, methods of sample selection, sample size, study type, age, STROBE score, and prevalence). These data abstraction forms were reviewed and eligible papers were entered into the meta-analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The random effects model was used for combining results of studies in meta-analysis. Variance for each study was calculated using the binomial distribution formula. The presence of heterogeneity was determined by the DerSimonian-Laird (DL) approach [12]. Significance level was <0.1 and I 2 statistic for estimates of inconsistency between studies. The I 2 statistic estimates the percent of observed between-study variability due to heterogeneity rather than to chance and ranges from 0 to 100 percent (values of 25%, 50% and 75% were considered representing low, medium and high heterogeneity, resp.). A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity whilst 100% indicates significant heterogeneity. For this review, we determined that I 2 values above 75 percent were indicative of significant heterogeneity warranting analysis with a random effects model as opposed to the fixed effects model to adjust for the observed variability [13]. This heterogeneity was further explored through subgroup analyses and metaregression. Univariate and multivariate approach were employed to assess the causes of heterogeneity among the selected studies. Egger test was conducted to examine potential publication bias. Data manipulation and statistical analyses were done using STATA software, version 10. P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

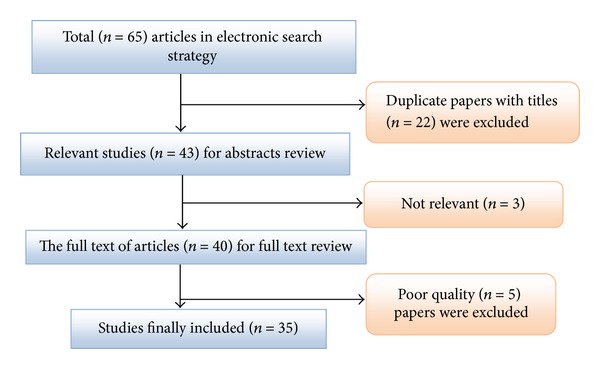

According to the literature search strategies, 65 studies were identified, but 30 studies were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 35 studies were published between 1995 and 2012 and included in meta-analysis (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Feature and characteristic studies included in study.

| Study number/author(s)/no. of reference | Place | Publication year | No. of population | Prevalence (%) | Instrument assessment | Cut point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Bahrami Dashtaki [14] | Tehran | 2005 | 100 | — | BDI | 15 |

| (2) Mohammadian [15] | Tehran | 2010 | 302 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (3) Alavi [16] | Mashhad | 2011 | 20 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (4) Hosseini [17] | Kermanshah | 2002 | 162 | 23.5 | BDI | 15 |

| (5) Bahadori Khosroshahi [18] | Zahedan | 2010 | 200 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (6) Biani [19] | Tabriz | 2008 | 571 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (7) Mohammad-Bigi et al. [20] | Arak | 2009 | 304 | 52.3 | BDI | 15 |

| (8) Amani et al. [21] | Ardabil | 2004 | 324 | 54.7 | BDI | 16 |

| (9) Dadkhah [22] | Ardabil | 2009 | 409 | 50.8 | BDI | 16 |

| (10) Pahlavan-Zadeh et al. [23] | Isfahan | 2010 | 50 | 38 | GHQ 28 | 22 |

| (11) Ranjbar-Kohan and Sajjadi Nejad [24] | Isfahan | 2010 | 40 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (12) Makvandi et al. [25] | Ahvaz | 2012 | 185 | — | BDI | 17 |

| (13) Makvandi [26] | Ahvaz | 2010 | 215 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (14) Ahmadi [27] | Ahvaz | 1995 | 200 | 45 | BDI | 16 |

| (15) Hasan Zadeh Taheri et al. [28] | Birjand | 2011 | 231 | 12.1 | BDI | 14 |

| (16) Moghareb et al. [29] | Birjand | 2009 | 400 | 45 | BDI | 16 |

| (17) Frotani [3] | Lar | 2005 | 134 | 42.5 | BDI | 16 |

| (18) Najafipour and Yektatalab [30] | Jahrom | 2008 | 150 | 45.4 | BDI | 15 |

| (19) Ildar Abadi et al. [1] | Zabol | 2002 | 175 | 64.3 | BDI | 16 |

| (20) Ahmadi-Tehrani et al. [31] | Qom | 2009 | 250 | 62.8 | BDI | 14 |

| (21) Partoi-Nejad [32] | Qom | 2011 | 600 | 33.3 | GHQ 28 | 22 |

| (22) Karami [33] | Kashan | 2009 | 208 | 48 | GHQ 28 | 22 |

| (23) Sooky et al. [34] | Kashan | 2010 | 307 | 35.8 | BDI | 16 |

| (24) Raenai et al. [35] | Kordestan | 2010 | 400 | 37.5 | BDI | 17 |

| (25) Eslami et al. [36] | Gorgan | 2002 | 202 | 15.5 | BDI | 16 |

| (26) Abdollahi et al. [37] | Golestan | 2011 | 132 | — | BDI | 16 |

| (27) Tavakoli et al. [38] | Gonabad | 2001 | 291 | 13.4 | BDI | 15 |

| (28) Ghasemi et al. [39] | Mashhad | 2009 | 780 | 28.6 | BDI | 15 |

| (29) Mohtashami-Poor et al. [40] | Mashhad | 2001 | 264 | 45.3 | BDI | 16 |

| (30) Abedini et al. [2] | Bandaradas | 2007 | 190 | 30.2 | BDI | 16 |

| (31) Hashemi et al. [41] | Yasuj | 2003 | 421 | 69.2 | BDI | 16 |

| (32) Hashemi et al. [42] | Hormozgan | 2004 | 452 | 62 | BDI | 14 |

| (33) Hashemi and Kamkar [43] | Yasuj | 2001 | 464 | 35.6 | BDI | 17 |

| (34) Baghiani Moghadam and Ehrampoosh [44] | Yazd | 2006 | 125 | 42.4 | BDI | 16 |

| (35) Baghiani Moghadam et al. [45] | Yazd | 2011 | 185 | 30 | BDI | 15 |

Figure 1.

Results of the systematic literature search.

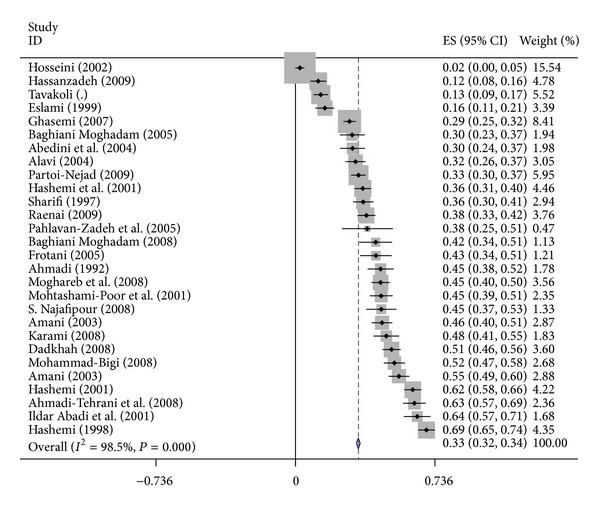

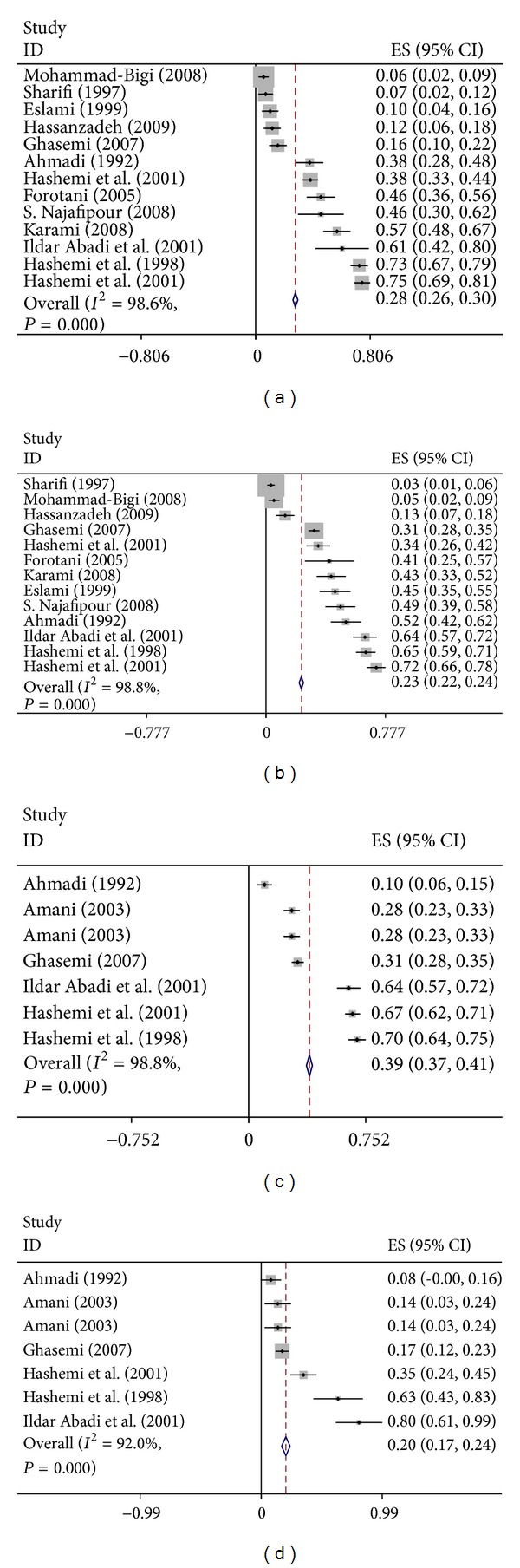

The overall prevalence of depression among university students was 33% (CI 95%: 32–34) (Figure 2). Prevalence of depression among subgroup including male and female students and single and married students was 28% (CI 95%: 26–30), 23% (CI 95%: 22–24), 39% (95%: 37–41), and 20% (CI 95%: 17–24) respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of student depression for random effects meta-analyses. (Squares represent effect estimates of individual studies with their 95% confidence intervals of depression with size of squares proportional to the weight assigned to the study in the meta-analysis. The diamond represents the overall result and 95% confidence interval of the random-effects meta-analysis.)

Figure 3.

Forest plots of student depression for subgroups analysis (forest plot (a) depression among male students, (b) among female students, (c) among single students, and (d) among married students).

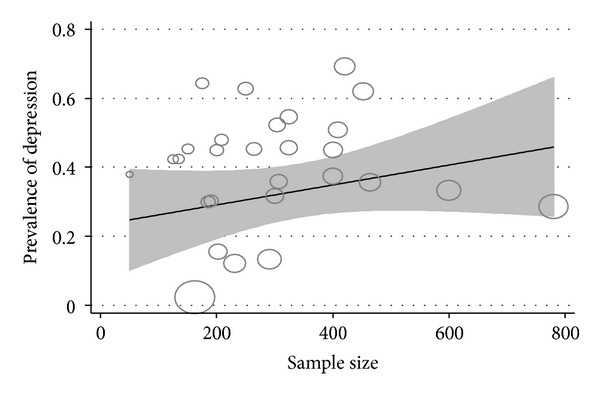

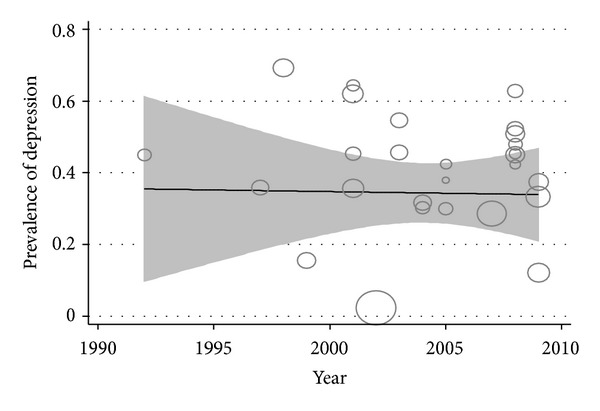

The meta regression of the prevalence of student depression again sample size of studies showed no statistically significant relationship (P = 0.66) (Figure 4). Scatter plot year of study and the prevalence of student depression meta regression showed a negative and no statistically significant relationship (P = 0.70). Since 1995, the student depression showed a stable trend (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Meta-regression plots of change in depression according to changes in continuous study moderator's sample size.

Figure 5.

Meta-regression plots of change in depression according to changes in continuous study moderator's year.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we have fully described our search strategy, study selection, data summary, and analysis to allow sensitivity analysis of any aspect of our approach. We have included every study that to our knowledge satisfies our inclusion criteria and employed techniques of estimation that allow integration of studies with high heterogeneity. In situations with high between-study heterogeneity (93.3%), the use of random-effects models is recommended as it produces study weights that primarily reflect the between-study variation and thus provides close-to-equal weighting [13].

In the current study, the Beck depression inventory (BDI) has been utilized to detect the prevalence of depression among university students. Although it is not designed for diagnostic purposes, its epidemiologic utility has been evaluated in several studies, which concluded that it is a reliable and valid instrument for detecting depressive disorders in nonclinical populations. Several studies support the BDI's usefulness in measuring and predicting depression in adolescent samples [46, 47].

The study showed that the prevalence of depression among university student was 33% (CI 95%: 32–34). Steptoe et al. showed that Asian countries had the highest level depressive symptoms [48], which was consistent with our result. The incidence of depression in our study was higher than in other studies, and as Bayram and Bilgel reported that depression were found in 27.1% of Turkish university students [49], Bostanci reported that out of all university students in Denizli, 26.2% had a BDI score of 17 or higher [50]. This variation has been explained to be due to cultural differences, different measurement tools, different methods, and different appraisal standards. University is an important transient life stage, with special academic, financial, and interpersonal pressures. Undergoing these transitions may lead to an increased risk of depression. However, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in the present study is a high incidence rate, more than that seen in average people. Most students who join university in Iran are leaving their homes for the first time. This might subject them to loss of the traditional social support and supervision, in addition to residing with other students and peer relationships. Moreover, there is a change in the style of learning from what the students are used to in school. These changes may act as risk factors to depression in university students in Iran.

We found no differences in depression between genders in our study. Similar to our results, some previous studies [49–51] showed that no differences in depression were observed among male and female students. This might originate from the fact that Iranian female university students have equal experience of the same pressure. However, some studies findings are contrary to our results and found higher levels of depression among female students [50–52].

We found that single students were susceptible to depression compared with married students. This may be because the single students face more stressful events than the married students, such as employment, economic, graduation, and marriage pressures. Contrary to our study, some studies showed that married students reported higher levels of depression [49].

One of the limitations of this study is that the difference in assessment tools and researchers varies in their choice of cut point according to the study location. Secondly, the more studies were observational and patients were not randomly chosen in addition our ability to assess study quality was limited by the fact that many studies failed to offer detailed information on selected subjects or valid data on important factors. Therefore selection bias and confounding seem inevitable. Thirdly, many of our data were extracted from the internal databases in Iran.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we found that depression is common in university students with no preponderance between males and females and in single students is higher than married ones. Our findings point to importance of screening of this vulnerable population and taking appropriate interventional measures to prevent the complications of depression. Further research studying sociodemographic factors and the effect of depression on the academic performance is needed.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported financially by Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Ilam, Iran.

References

- 1.Ildar Abadi E, Firouz Kouhi M, Mazloum S, Navidian A. Prevalence of depression among students of Zabol Medical School, 2002. Journal of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. 2004;6(2):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abedini S, Davachi A, Sohbaee F, Mahmoodi M, Safa O. Prevalence of depression in nursing students in Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. Hormozgan Medical Journal. 2007;11(2) 42:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frotani M. Depression in students of higher education centers. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;18(41-42):13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan JL. Prevention of depression in the college student population: a review of the literature. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2012;26(1):21–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eller T, Aluoja A, Vasar V, Veldi M. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in Estonian medical students with sleep problems. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23(4):250–256. doi: 10.1002/da.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Glazebrook C. Reliability of a shortened version of the Zagazig Depression Scale and prevalence of depression in an Egyptian university student sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53(5):638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmoud JSR, Staten RT, Hall LA, Lennie TA. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2012;33(3):149–156. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.632708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reavley N, Jorm AF. Prevention and early intervention to improve mental health in higher education students: a review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2010;4(2):132–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castaldelli-Maia JM, Martins SS, Bhugra D, et al. Does ragging play a role in medical student depression—cause or effect? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;139(3):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Der Simonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ades AE, Lu G, Higgins JPT. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Medical Decision Making. 2005;25(6):646–654. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahrami Dashtaki H. Spirituality as a way of teaching effectiveness in reducing depression in students. Counseling Research & Developments. 2005;5(19):47–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammadian Y. Evaluating the use of poetry to reduce signs of depression in students. Journal of Ilam University of Medical Sciences. 2010;18(2):9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alavi K. Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy group practices (with emphasis on the fundamental components of pervasive awareness, distress tolerance, and emotional regulation), on depressive symptoms in students. The Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2011;13(50):35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosseini A. Introduction of changes in medical students’ attitudes and Depression—using group education. The Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2002;4(13-14):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahadori Khosroshahi J. Relationship between stressful life events and sense of humor with depression in students. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2010;9(51):27–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biani A. The relationship between religious orientation and depression and anxiety in students. The Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2008;10(39):191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammad-Bigi A, Mohammad-Salehi N, Ghamari F, Salehi B. Prevalence of depressive symptoms, general health status and risk factors in students of Arak University dormitory 2008. Arak Medical University Journal. 2009;12(3) 48:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amani F, Sohrabi B, Sadeghieh S, Mash’oufi M. Prevalence of depression in students of medical sciences 2003. Journal of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences. 2004;4(11):7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dadkhah B. Prayer association with depression in medical students. Teb va Tazkiyeh. 2009;18(3-4):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pahlavan-Zadeh S, Kiassat Poor M, Nassiri M. Depression in athletes and non-athlete students of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences. 2006;4(1-2) 8:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranjbar-Kohan Z, Sajjadi Nejad M. Effect of assertiveness training on self-esteem and depression in university students. Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2010;17(4) 45:308–316. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makvandi B, Heidari A, Shahany M, Najarian B, Askari P. The relationship between alexithymia and anxiety and depression in female students of Islamic Azad University of Ahvaz. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology. 2012;13(1) 47:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makvandi B. The relationship between alexithymia and anxiety and depression in female students of Islamic Azad University of Ahvaz. Journal of Women in Culture Arts. 2010;2(6):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmadi J. Rate of depression among medical students (Ahwaz 1992) Thought and Behavior in Clinical Psychology. 1995;1(4):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasan Zadeh Taheri M, Moghareb M, Ekhbari E, Raissun M, Hassanzadeh Taheri M. Prevalence of depression among new students of Birjand University of Medical Sciences in the year 2009-2010. Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2011;18(2) 47:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moghareb M, Qnadkafy M, Rezaei N. The relationship between prayer and depressive in Birjand University of Medical Sciences. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2009;6(1–4) 24:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.NajafiPour S, Yektatalab S. The prevalence of depression in University of Medical Sciences of Jahrom. Journal of Jahrom Uiversity of Medical Sciences. 2008;6(6):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmadi-Tehrani H, Haidari A, Kachuei A, Moghiseh M, Irani M. The association between depression and religious attitude towards Qom University of Medical Sciences, 2008. Qom University of Medical Sciences Journal. 2009;3(3) 11:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Partoi-Nejad. Comparison of depression in medical college students and scholars of Qom Seminary, 2008. Qom University of Medical Sciences Journal. 2011;5(3):49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karami M. Depression in college of paramedical kashan university of medical sciences, 2008. Journal of Urmia Nursing and Midwifery Faculty. 2009;7(3):166–172. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sooky Z, Sharifi K, Tagharrobi Z, Akbari H, Mesdaghinia E. Depression prevalence and its correlation with the psychosocial need satisfaction among Kashan high-school female students. Feyz Journal of Kashan University of Medical Sciences. 2010;14(3, serial 55):257–263. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raenai F, Ardalan F, Zaheri F. Attitude and practice of prayer and its relationship with depression in students of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences in 2009. Teb va Tazkiyeh. 2010;19(4):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eslami A-A, Vakili M-A, Faraji J. Depression among medical students of Gorgan and its relation to spend leisure time. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2002;4(9):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdollahi A, Asaiesh H, Jafari Y, Rezaeian M. University of Medical Sciences Students’ Mental Health: arrival in university and after one year. Journal of Gorgan Bouyeh Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery. 2011;8(1) 19:52–59. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tavakoli J, Ghahramani M, Haddizadeh Talasaz F, Chamanzari H. Mental health status of in young smokers and non smokers Gonabad city. Horizon of Medical Sciences. 2001;9(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghasemi M, Rajbnia F, Seadtian V, Meshkat M. Depression and its influencing factors in medical and paramedical students of Islamic Azad University of Mashhad, 2008-2009. Journal of Medival Science. 2009;4(3) 15:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohtashami-Poor E, Mohtashami-Poor M, Shadlou Mashhadi F, Emadzadeh A, Hassan Abadi H. Prayer relationship with depression in college students Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Horizon of Medical Sciences. 2001;9(1):61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashemi N, Baghri M, Ghafarian H-R. Factors associated with depression in university students Yasuj—2001. Journal of Medical Research. 2003;2(1) 5:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashemi N, Hoseini Z, Shahami M-A. Epidemiological studies of depression among university students Yasouj. Teb va Tazkiyeh. 2004;13(2):p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashemi N, Kamkar A. Prevalence of depression in students of medical sciences. Armaghan Danesh, Biomonthly Yasuj University of Medical Research Sciences Journal. 2001;6(21):14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baghiani Moghadam M-H, Ehrampoosh M-H. Depression in of medical sciences students of Yazd and its relationship to academic factors. Tolooe Behdasht. 2006;5(1-2):p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baghiani Moghadam M-H, Ehrampoosh M-H, Rahimi B, Aminian A-H, Aram M. Assessment of depression among college students in health and nursing Yazd University of Medical Sciences in 2008. Journal of Medical Education Development Center. 2011;6(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganesh SK, Animesh J, Supriya H. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors using Beck Depression Inventory among students of a medical college in Karnataka. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;54(3):223–226. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teri L. The use of the Beck Depression Inventory with adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1982;10(2):277–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00915946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steptoe A, Tsuda A, Tanaka Y, Wardle J. Depressive symptoms, socio-economic background, sense of control, and cultural factors in university students from 23 countries. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;14(2):97–107. doi: 10.1007/BF03004175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bayram N, Bilgel N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43(8):667–672. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bostanci M, Ozdel O, Oguzhanoglu NK, et al. Depressive symptomatology among university students in Denizli, Turkey: prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Croatian Medical Journal. 2005;46(1):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grant K, Marsh P, Syniar G, et al. Gender differences in rates of depression among undergraduates: measurement matters. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25(6):613–617. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wade TJ, Cairney J, Pevalin DJ. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: national panel results from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):190–198. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]