Abstract

The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program (VAQS) was established in 1998 as a post-graduate medical education fellowship to train physicians in new methods of improving the quality and safety of health care for Veterans and the nation. The VAQS curriculum is based on adult learning theory, with a national core curriculum of face-to-face components, technologically mediated distance learning components, and a unique local curriculum that draws from the strengths of regional resources.

VAQS has established strong ties with other VA programs. Fellows’ research and projects are integrated with local and regional VA leaders’ priorities, enhancing the relevance and visibility of the fellows’ efforts and promoting recruitment of fellows to VA positions.

VAQS has enrolled 96 fellows from 1999 to 2008; 75 have completed the program and 11 are currently enrolled. Fellowship graduates have pursued a variety of career paths: 20% are continuing training (most in VA); 32% hold a VA faculty/staff position; 63% are academic faculty; and 80% conduct clinical or research work related to health care improvement. Graduates have held leadership positions in VA, Department of Defense, and public health.

Combining knowledge about the improvement of health care with adult learning strategies, distance learning technologies, face-to-face meetings, local mentorship, and experiential projects has been successful in improving care in VA and preparing physicians to participate in, study, and lead the improvement of health care quality and safety.

The implementation of best practices supported by evidence to improve patient care is a critical aspect of translational research.1,2,3 It is estimated that it takes approximately 18 years to widely implement efficacious interventions. To improve quality of care, it is necessary to have evidence of the effectiveness of new practices, a sensible health policy framework for funding, and organizational leadership that can lead improvement. Furthermore, measuring quality of care is a key aspect of current pay-for-performance programs designed to improve overall care4 and quality measurement programs.5,6 Advancing new knowledge, as well as training and educating health care providers are necessary components of improving quality of care.

The issues of quality and safety as part of professional formation are well established.7,8 Reference to these issues can be found as far back as the original Oath of Hippocrates.9 A practitioner not only needs to demonstrate the knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to quality and safety but also must be competent in these areas. A shift in the educational focus has been led by accrediting organizations. The Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) developed six competencies10 requiring that all residency programs be able to show that residents demonstrate competence in the areas of patient care, medical knowledge, professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI), and systems-based practice (SBP). The latter two, PBLI and SBP, had been underdeveloped in prior curricula.

Residency programs and specialty boards are quickly developing curricula to reshape the general knowledge and skills physicians need to practice in the 21st century. However, such curricula in residency programs will not adequately provide the training or experience needed to generate new knowledge or science in either quality or safety. In addition, career paths that are available to physicians who wish to pursue jobs that include improving quality and safety as a distinct aspect of their professional work are few in number.11 To attempt to fill these gaps, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program (VAQS) was designed to train physicians in the scholarship of improving quality and safety. The program aims both to advance the science of and develop leaders in the research, practice, and education of quality and safety issues.

Overview of VAQS Fellowship

The VAQS Program was designed and implemented by Dartmouth Medical School faculty in coordination with leaders in the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) as a two-year post-residency fellowship for physicians interested in further developing the scholarship of the improvement of health care. It is one of several Advanced Fellowship Programs offered in VA through OAA.12 VAQS began in 1998 and enrolled its first fellows in July 1999. The Program aims are to:

apply knowledge and methods of health care improvement to the care of veterans;

innovate and continually improve health care;

teach health professionals about health care improvement;

perform research and develop new knowledge for the ongoing improvement of the quality and value of health care services; and

enrich Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA’s) clinical workforce with experts in research and application of health care quality improvement skills.

Fellows completing this advanced fellowship program should demonstrate competence in the following areas: (1) design, implementation, management, and monitoring of quality improvement systems for improvement to veterans' health care; (2) design, implementation, and facilitation of quality improvement research projects; (3) teaching health professionals about methodologies and activities they can use to improve care; and (4) using health care informatics to improve systems of care.

The VAQS Program used a new educational design for VA Advanced Fellowships. The Program was designed according to a hub and spokes model. Dartmouth, because of its history of research in quality and safety and its existing graduate curriculum, functions as the hub site for the program. VAQS staff at Dartmouth are responsible for coordination of all educational activities as well as the national leadership and coordination of the Program. The six VAQS sites each are led by a Senior Scholar who coordinates the site activities and serves as the primary mentor for fellows. The Senior Scholar is responsible for local recruitment and for all activities related to fellows’ projects and other academic activities outside the main curriculum in health care quality improvement created and delivered by Dartmouth. Each site can enroll as many as two fellows per year in the two-year program. Thus, the total compliment of fellows is up to 24 fellows annually. Additional details of the VAQS Program structure and organization are described elsewhere.13

Although the curriculum is designed over a two year course of study, its delivery is based on an academic year calendar. The structure of the educational activities in the Program is composed of three major elements: face-to-face meetings, two-way interactive video conferences (TWIV) and complementary distance learning strategies, and fellow projects. There are three face-to-face meetings of the VAQS Program scheduled throughout the academic year. The first is a 4-day Summer Institute each August at the hub site in Vermont. The second is a 1-day meeting in conjunction with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s National Forum in December. The third is a 1-day meeting in conjunction with the VA Health Services Research and Development Meeting in February or March. Each meeting brings together fellows and faculty from each site, Dartmouth faculty and staff, and leaders from VA. Each meeting has a theme and provides time for presentation of fellows’ work as well as interaction and discussion with invited guest faculty. The face-to-face meetings are specifically designed to take advantage of educational objectives that require social components to learning, including such topics as establishing shared values and goals, leadership development, enhancement of teaching skills, and communication skills.

The TWIV sessions occur approximately every two weeks and total 25 for each academic year (List 1). They are two hours in length and include small didactic sessions, presentations of fellows’ work, and live online exercises. The curriculum and assigned readings are distributed quarterly and are now available utilizing a web-based curriculum management program. Assignments for each session are given at the end of the preceding session.13 Topics covered in year one of a fellow’s experience are revisted in year two using different readings, assignments, and discussions to avoid duplication and promote enhanced learning of curricular content.

List 1. Session Titles for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program Two-Way Interactive Video Curriculum.

Introduction and Logistics; Systems Failure, Medical Errors

Quality Is Personal

Prior Leaders of Improvement

Health Care as a System; VA as a System

Personal Improvement Projects

Process and Outcomes Thinking

Change Concepts

Learning Cycles for Improvement

Variation & Statistical Process Control

Benchmarking

Understanding Patient Perspectives

Analyzing Satisfaction Data

Financial Data and Cost Analysis

Working Together, Collaboration

Conflict Management, Negotiation Theory

Teaching and Learning

Research Design for Improvement Work

Models for Understanding Complexity

Ethics and Quality Improvement

The Clinical Microsystem Model

High-Performing Microsystems

Making Change in a Microsystem

Measurement of Microsystem Performance

Competencies & Educational Evaluation

Strategic and Organizational Improvement

Fellows’ research and quality improvement projects make up the third component of the educational experience. These are largely created and mentored locally at each VAQS Program site. The Senior Scholars and site faculty play a critical role in the selection, development, and completion of these efforts. Progress updates and opportunities for feedback about fellows’ projects are built into the TWIV sessions and the VAQS meetings. Finally, several VAQS sites enable fellows to participate in an advanced degree program of their choosing through their affiliated university partner. In addition, fellows have many opportunities to participate in ongoing quality and safety efforts at their VA facility or within their regional VA Network. These opportunities are encouraged but not mandated in the VAQS curriculum.

Evolution of VAQS

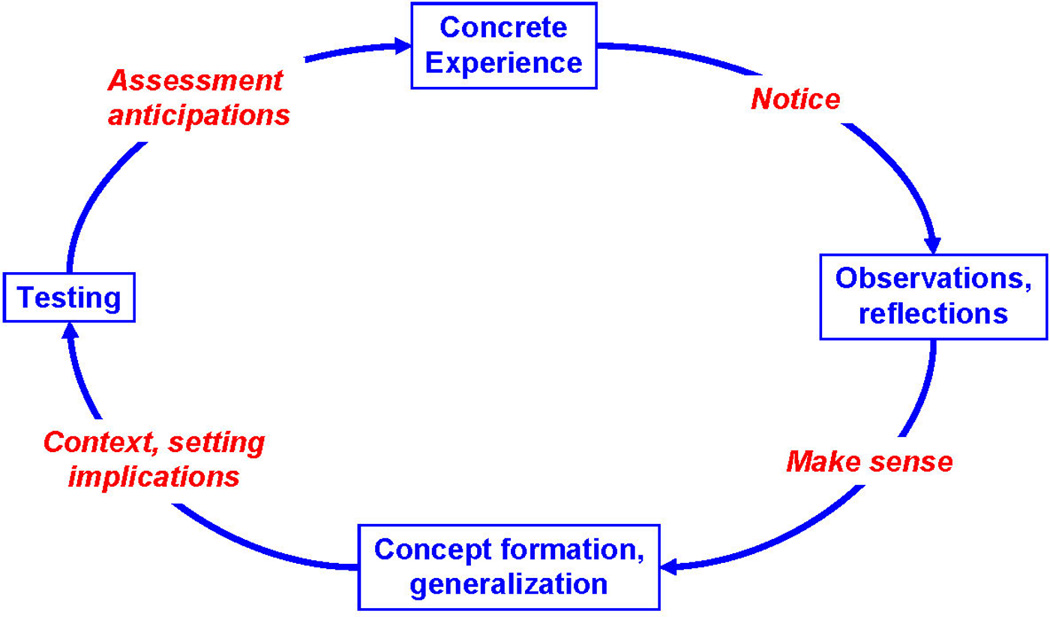

The VAQS curriculum content has evolved since its inception. At its core, the curriculum employs Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning (Figure 1).14 The cycle begins with a concrete experience. Promoting awareness and the ability to notice details leads to observations and reflections about the experience. The observations develop into concepts through a process of making sense of what has been noticed. Further consideration of the context, setting, and implications promote testing of the concept. Assessment of the test completes the cycle of learning. Thus, the VAQS curriculum promotes learning through specific efforts to improve care rather than an abstract discussion of concepts and theories. This design was chosen because of the importance of skill development in understanding and innovating in issues related to quality and safety. The initial content was adapted to fit the interactive video conferences from approximately 160 hours of course material used at Dartmouth in Masters-level graduate programs. The material is part of three courses which are specifically focused on the improvement of quality and safety. Course content covers topics such as concepts and theories of health care improvement, measurement and analysis of quality and safety issues, and clinical microsystems.

Figure 1.

Conceptual design of experiential learning in VAQS curriculum

The VAQS faculty, through review of existing literature and their own experience, learned and applied several key principles and techniques to promote engagement and learning using a video conference medium.15,16,17 They encountered several challenges in the initial use of this technology and identified some essential components in successfully addressing these challenges: sharing leadership by allowing learners to be teachers to the group; avoiding long periods of time (more than ten minutes) when only one person is speaking; assigning multiple roles to participants and rotating those responsibilities to encourage involvement; creating just-in-time assignments to engage learners in content; being flexible with time and material to allow for rich discussion to emerge; adapting curricular topics based on the interests of learners; being aware that some topics are not immediately conducive to distance learning strategies; and mastering nuances in the technology of the learning media, such as delays in video and audio transmission. Faculty use other strategies as well to enhance this distance learning. First, sessions are highly facilitated to assure interaction between all participants. Presenters and discussants are assigned prior to sessions, and participants are polled periodically to assure interaction and participant engagement. Also, sessions are augmented by web-based technologies that facilitate distribution of education materials and additional asynchronous interaction, such as discussion boards.

The VAQS curriculum is updated quarterly to promote interest and reinforce learning. Assignments and specific activities are updated on an annual basis – thus, on any given two-year cycle, fellows receive the same content only once. Fellows evaluate each session using a web-based anonymous survey. Comments from fellows are reviewed and incorporated into the next session or are addressed in other appropriate aspects of the curriculum. This dedication to using the feedback from fellows in meaningful ways has helped to enhance the personal stake that each fellow has in the experience of his or her colleagues.

Assignments for each session are grounded in the work of the participating fellows. Thus, it is common that a fellow will have several opportunities to present different aspects of a research or quality improvement project during the course of the year to the entire VAQS group. This provides a mechanism for bidirectional learning – the fellow presenting receives feedback and assistance from colleagues, and the other fellows learn about each other’s work. For example, when discussing how to teach about improvement, the fellows from Birmingham presented their elective model for teaching medical students at the University of Alabama Birmingham. This elective was their first foray into teaching, and they shared successes and failures and received feedback from fellows and faculty at all of the sites. This process is repeated during each TWIV with topics such as leadership, research design for improvement, and statistical analysis for improvement. These activities promote the feeling of a community of learners in the fellowship.

Integration of VAQS with the VA Organization

To be selected as a VAQS site, the support of local and network leaders was essential. Initially, this support has come in the form of 25% full-time equivalent (FTE) for the Senior Scholar; however, such FTE support was for a time-limited period. Subsequent support from operational leaders is negotiated by faculty at each site. Fellows’ support and connection to operational leaders varies across sites. Some have created strong connections, with fellows being regularly involved in local and regional quality and safety efforts. Such efforts have led fellows to leadership positions at the facility or regional level upon graduation. Former fellows have accepted positions as Director, Inpatient Quality Improvement, and Network Quality Management Officer, among others.

Other sites have attracted support by developing a research portfolio and successfully securing resources for research from VA. Examples of these programs include: Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Center for Quality Improvement Research in Cleveland, OH; HSR&D Research Enhancement Award Programs in Birmingham, AL, San Francisco, CA, and White River Junction, VT; Center for Research in the Implementation of Innovative Strategies in Practice in Iowa City, IA; and Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers in Cleveland, OH, and Nashville, TN. Fellows and graduates have contributed significantly to these efforts. This intimate connection between VAQS sites and VA research resources, combined with extensive mentoring by faculty, enabled four graduates to receive career development awards and independent funding. In both career paths, clinical researcher or clinical leader, a key element of success for each site has been a close partnership with other VA resources and acknowledged VA leaders at the site.

The national VAQS Program has sought to systematically connect fellows to multiple aspects of VA infrastructure in addition to conducting their local work at each site. This has largely been done through the curriculum – inviting VA leaders to participate in video conferences and program meetings. Examples of these types of interactions are described in Table 1. These interactions have provided opportunities for fellows to serve on national committees and have provided research opportunities for fellows. Also, VA leaders learn about and interact with the program (both with fellows and faculty) through these encounters. VA leaders have become teachers and contribute to the learning of fellows and faculty through presentations and workshops.

Table 1.

Interactions between Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Quality Scholars (VAQS) Fellowship and Other VA Organizations

| VA organization | Types of interactions |

|---|---|

| National Center for Patient Safety | Attendance at program meetings |

| Participation in two-way interactive videoconferences (TWIVs) | |

| Fellows’ participation in national collaborative projects | |

| Office of Quality and Performance | Attendance at program meetings |

| Participation on TWIVs | |

| Fellows’ participation in internships | |

| Office of Research – Heath Services Research and Development (HSR&D) | Integration of annual meeting into VAQS |

| Joint meeting with HSR&D Career Development Awardees | |

| Faculty participation in HSR&D activities | |

| Office of Research – Quality Enhancement Research Initiative | Attendance at program meetings |

| Fellows’ and faculty’s participation in key committees and projects | |

| Patient Care Services | Participation on TWIVs |

In 2002, leaders from VA presented information about the Secretary’s Robert W. Carey Performance Excellence Awards and the process for selecting winners at the VAQS summer program in Vermont. These awards recognize VA organizations with exemplary approaches to systems management that achieve excellent results for veterans. The foundation of the awards is the Malcolm Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence. Subsequently, six fellows completed training in the Baldrige examination process and certification. These fellows then participated in the national VA effort to judge and select this award for quality.

Leaders from the VA National Center for Patient Safety (NCPS) have regularly interacted with fellows. These interactions have resulted in fellows participating in and leading root cause analysis teams at various facilities, all with the goal to improve safety and quality of care. VA has conducted several national collaborative efforts to improve care and operations.

Connections formed with VA leaders during VAQS have allowed fellows and faculty to take on leadership roles in such large-scale efforts as Medical Team Training, Reducing Patient Falls, and Improving Processes for Compensation and Pension. Each of these was a national VA Collaborative to improve care for Veterans. Each Collaborative was designed based on a model for Breakthrough Series established by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and involved over one hundred teams throughout VA (Note: I can provide references if helpful). VAQS fellows and faculty served as coaches for teams. Such connections throughout VA have been possible through efforts by the Dartmouth hub site to integrate VA leaders and experiences about their work into the curriculum. Moreover, VAQS faculty have a key role in linking fellows with VA leaders, projects and other resources because of their connectedness throughout VA. Without faculty members’ knowledge and relationship within and across VA, many of the opportunities described above would not have been possible.

Impact of VAQS on Improving Quality and Safety in VA

A major goal of the VAQS Fellowship is for fellows to complete a project that improves the quality of care for Veterans and the nation. Fellows’ projects typically focus on the quality of care at a specific VA facility or its affiliated university. Many projects also result in publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Examples of single-facility projects include automation of an order for advanced directives at a VA nursing home18; improving door-to-balloon time for patients with acute myocardial infarction using quality improvement methods19; improving emergency caesarean delivery response times at a rural community hospital20; and using quality improvement methods to enhance medication reconciliation in a VA facility.21

Although some projects are conducted within a single facility, VA’s infrastructure, which organizes community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) and hospitals within regional networks, has allowed many fellows to extend their projects beyond a single facility. One example of a regional project was a step-wise intervention encouraging patient-focused care that improved hypertension control in Veterans.22 Another regional improvement project expanded the role of certified diabetic nurse educators in diabetic care management with the use of an algorithm to titrate insulin doses in primary care community clinics. This project led to a significant improvement in diabetic control for Veterans in these clinics and improved physician satisfaction.23

A few projects have been national in scope. One such initiative created an electronic tool based on VA’s national electronic health record to improve processes used in resident physician handoffs at the end of shifts. Another national project organized the process of medication reconciliation across VA Networks, creating a unified approach to this challenging issue. Further, many fellows’ projects have focused on understanding issues in quality and safety by examining existing VA data. Fellows’ work has clarified the risk of indwelling urinary catheters in geriatric patients24; explored medication prescribing quality25; and identified racial differences in coronary revascularization.26 In addition, fellows have focused their work on educational processes involving training of medical students and resident physicians.27,28,29

Overall, the VAQS fellowship provides a tremendous range and depth of opportunities for fellows. The “hub and spoke” program design creates a strong central curriculum for fellows, but allows considerable mentoring by local senior scholars. This provides all fellows with a strong foundation in quality improvement as well as the opportunity to pursue local projects and research opportunities that are unique to their VA and to their university affiliate.

Influence of VAQS on Fellows’ Career Choices

Training in the VAQS Program has generally created two types of academic physicians – clinician leaders and clinician researchers. So far, 20% (15 of 75) of graduates currently have a training position in a clinical medical subspecialty (9 in VA); 32% (24 of 75) of graduates currently have a VA faculty/staff position; 63% (47 of 75) of graduates are in academic faculty positions; 80% (60 of 75) of graduates are in clinical or research positions related to the improvement of health care.

Specific examples of the types of positions fellows have accepted after the training are noted in List 2. Examples of leadership positions span the domains of research, education, clinical operations, and public health. Notably, many former fellows state that the job they currently hold did not exist when they were in fellowship (e.g., Director of Inpatient Quality Improvement, National Director of Medication Reconciliation, Director of the Office of Research and Innovation in Medical Education, Quality Director, Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute), indicating that their positions were created specifically for them. In addition, many graduates report increasing success in negotiating jobs that include support for work on quality and safety not previously in place before they applied. In short, the knowledge and skills that our graduates possess are in demand by VA and non-VA employers.

List 2. Examples of Clinical Leadership and Educational Leadership Positions Currently Held by Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Quality Scholars Fellowship Graduates.

Clinician leader

VA

Network Quality Management Officer

Director, Inpatient Quality Improvement

Director, Mental Health Team in Primary Care

Director, Traumatic Brain Injury Clinic, Psychiatry Service

Co-Director, Skeggs Cleveland VA Diabetes Center

Chief of Admitting and Urgent Care Center

Quality Management Physician Advisor

Non-VA

Chief, Pulmonary Diseases, Critical Care, Sleep Medicine (Department of Defense)

Medical Director, Medical Management

Vice President and Chief Quality Officer

Medical Director, Quality and Safety Institute

Rural Health Quality Specialist

Medical Director, Acute Care Unit for Elders

Medical Director for Quality Improvement

Director, Center for Vaccine Sciences

Quality Director, Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute

Assistant Medical Director, Vanderbilt Center for Surgical Weight Loss

Education leader

Dean of Research and Evaluative Sciences

Assistant Dean for Research and Innovation

Associate Director, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Leadership Preventive Medicine Residency Program

Fellowship graduates have found success in research careers, as well. Three graduates have received Career Development Awards from the VA Health Services Research and Development Office. A fourth graduate has received a similar Career Development Award from the National Institute of Health. Graduates have published extensively. A recent literature search using PubMed identified 110 peer reviewed articles authored by prior fellows from 2006–2008 alone.

Most important for the fellowship, many fellows have taken faculty positions at the site or within the VA Network where they trained. Of the 75 graduates from VAQS, 33 have faculty positions associated with current program sites (three in Birmingham, four in Cleveland, four in Iowa City, nine in Nashville, four in San Francisco, and nine in White River Junction). This has enhanced the number of faculty available to future fellows for advice and mentoring. Two of these former fellows have even been appointed Associate Fellowship Program Directors to formalize their relationship with and leadership in VAQS.

Future Directions

Training mid-career faculty

Given the success of the VAQS Program over the past 10 years, there are plans for future development and expansion in many areas of the program. First is the training of current VA faculty who are not part of VAQS. Participating in the VAQS Program is a challenge for many current VA faculty because of issues with both time and compensation. However, many physicians in the middle of their careers recognize and seek out opportunities to obtain additional training and skills to enhance their professional development. The VAQS Program has recognized this need, especially in seeking to fulfill its mission to train the leaders of the scholarship of quality and safety. Thus, the Program has enrolled 21 mid-career physicians as fellows, constituting 33% of VAQS graduates. In discussing the experience with these graduates and others who chose not to enroll in the fellowship, the requirement to take two years from one’s current career path for this training remained an important barrier.

Recognizing the need to adapt to meet the needs of VA, one program site leader developed a specific fellowship experience for a faculty person that required only one year of additional training. This required approval of OAA and the Dartmouth hub site, both of which contributed to and endorsed the proposal fully. The design of the experience was tailored to meet both the faculty member’s specific learning needs and the needs of the VA Facility. The Facility Director assisted in creating the experience and approved a reduction in the faculty person’s time to 50% FTE to participate in this experience. The faculty member participated in all aspects of the VAQS Program, and she was mentored specifically during this time by the site director. The experience resulted in several publications and the development of a research career development award application. The experience was viewed as a success and there are plans to work to replicate this model at other VAQS sites in future.

Inclusion of nurses

The inclusion of doctoral or post-doctoral nurses in VAQS is among the next steps for the program. The VAQS faculty have long recognized the potential benefit of making the program interprofessional.30 Now, in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-funded Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) initiative, the first pre- and post-doctoral nurse fellows enrolled in VAQS in July 2009. This partnership allows support of Nurse Senior Scholars at all VAQS sites affiliated with a School of Nursing.

The addition of nurses to VAQS is a full integration, not a parallel track; thus, nurse and physician fellows participate together in curriculum and projects. Mentoring of fellows occurs both within and across professions (e.g., nurse-nurse, nurse-physician, physician-nurse, physician-physician). The existing curriculum has been modified to include interprofessional activities, such as working in teams, understanding professional mental models, and preparation. Reading from both medicine and nursing journals has been incorporated in the curriculum. Finally, nurse and other health professional faculty act as guest speakers for each program meeting. This further enhances the interprofessional experience for all fellows.

Enhancing reflection and learning through program assessment

The VAQS Program has an extensive evaluation system for its educational experiences. Each video conference, meeting, and program event is evaluated using a real-time web-based survey. In addition, fellows and alumni are surveyed annually. The VAQS National Director conducts semi-annual interviews with each. Faculty at each site regularly meet with fellows and provide feedback. The evaluation methods (in person, anonymous, quantitative, and qualitative) have provided rich information on a regular basis to continually adapt, update, and reassess the Program. This learning-based rather than judgment-based approach to evaluation has also helped us engage our fellows, faculty, and graduates as partners in the redesign of the Program.

Despite the volume and richness of the information we collect, we struggle to define clearly what works in VAQS. We have recently adopted a new evaluation strategy based on the realist evaluation work of Pawson and Tilley.31 This evaluation method has been used to study complex social interventions, such as crime prevention and international feeding programs.32 The method requires that the evaluator develop a hypothesis of how the intervention works. It then asks the evaluator to further describe the linkage of specific elements of the context for the intervention, the mechanism through which the intervention works, and the outcome that is used to assess this effect. Realist evaluation employs a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to assess the intervention. The result of the evaluation is a middle-range theory about how the program works. The theory generally addresses the question of what works where, for whom, under which circumstances, and why. We are currently employing this approach and have discovered many insights about our sites and the educational programs. We intend to report further on the design and results of this evaluation when it is complete.

Conclusions

The VAQS Program has successfully trained 75 physicians since its inception in 1999. Graduates of the fellowship have pursued careers in clinical leadership, research and education, many of which were employment opportunities that were developed specifically to take advantage of the graduate’s unique skills. The fact that 60% of graduates have found jobs in academic settings suggests that VAQS training has helped to address the challenge of a lack of academic career pathways in quality improvement noted by Shojania and Levinson.11 As a group, the program alumni have published more than 300 articles in peer-reviewed journals. Many graduates have held and continue to hold important positions of influence locally, regionally, and nationally in VA and the private sector. From this perspective alone, the VAQS Program has demonstrated a clear impact in leading the development of the scholarship of quality and safety.

We recognize the lessons we describe here are results of the experience of only a single training program; however, there are no comparable doctoral-level training programs that exclusively focus on advancing the scholarship of health care improvement. We have certainly benefited from the experience and model of the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program33 (CSP), but the design and focus of this nationally recognized exemplary program is different from ours. VAQS started out with a structure based on the CSP in 1999, but since then the VAQS curriculum has evolved dynamically and now has little in common with the curricular structure or content of CSP. A key difference between the two programs is the strong national curriculum in VAQS. This promotes ongoing integration of fellows and faculty across sites throughout the year; the only curricular integration in the CSP takes place at annual meeting. Otherwise, CSP sites engage in parallel activities that are not integrated.

Our experience in VAQS has developed at six sites which are distributed across the United States and demonstrates that such a training model is not limited to a specific site or region. In addition to taking advantage of local differences and priorities, we have encouraged intentional collaboration among and across our sites. This has enhanced the reach and scope of many efforts. Furthermore, the impact of the VAQS Program is not limited to the VA system. Although the major focus of the work of fellows in the VAQS Program is in VA, the successes extend into the university affiliates of each VA facility and to the community as well.

The VAQS Program has been successful in many ways. It has promoted the integration of fellowship training with other aspects of the VA organization; used available distance learning technology combined with in-person meetings to create a national community of learners; linked fellows’ projects to VA strategic priorities to improve quality and safety; and assisted graduates in garnering clinical leadership and research positions. Based on these accomplishments, the VAQS Fellowship should be considered as a model for future VA learning experiences. In addition, aspects of VAQS, such as the use of a core curriculum, connecting learners from different sites, and use of graduates to enhance and promote the relevance of learning, may be adaptable to other training settings in which the structure of a full two-year fellowship is not possible.

The need for training health professionals to lead, study, and educate others about the improvement of quality and safety is clear. VA was a vanguard in this effort 10 years ago with the development of the VAQS Program. Today, this program provides an example of a fellowship training experience that has a national scope with local and regional impact on the care of Veterans. VAQS uses a combination of distance learning technology, in-person meetings, connection with leaders, and experiential learning through projects. The novel design of the Program may serve as an example for others to replicate as the health care community works to close the quality chasm that continues to exist today.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to Leslie K. Walker, Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship (VAQS) National Program Coordinator, for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript and her ongoing support of VAQS.

The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship (VAQS) is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA). Drs. Splaine and Batalden are supported by OAA to lead, implement and oversee the VAQS Program.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not represent the opinion of VA.

Contributor Information

Mark E. Splaine, Associate Professor of Medicine and Community and Family Medicine, Center for Leadership and Improvement, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire..

Greg Ogrinc, Associate Professor of Medicine and Community and Family Medicine, Senior Scholar Dept. of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, White River Junction, VT and Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, New Hampshire..

Stuart C. Gilman, Director, Advanced Fellowships, VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Washington, D.C..

David C. Aron, Professor of Medicine, Senior Scholar Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program, and Director, Center for Quality Improvement Research, Louis Stokes Cleveland Dept. of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio..

Carlos Estrada, Associate Professor of Medicine, Senior Scholar Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program, Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama..

Gary E. Rosenthal, Professor of Medicine, Senior Scholar Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program, and Chief, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Iowa City Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, University of Iowa School of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa..

Sei Lee, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Associate Fellowship Director Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program, and Chief, Geriatrics Section, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California..

Robert S. Dittus, Professor of Medicine, Senior Scholar Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program, and Chief, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Nashville Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee..

Paul B. Batalden, Professor of Pediatrics and Community and Family Medicine, and Director, Center for Leadership and Improvement, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire..

References

- 1.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr, Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289:1278–1287. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg RN. A National Crisis and a Call to Action. Translating Biomedical Research to the Bedside. JAMA. 2003;289:1305–1306. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salanitro AS, Estrada CA, Allison JJ. In: Implementation research: beyond the traditional randomized controlled trial. Essentials of Clinical Research. Stephen Glasser, editor. Springer Science; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of Research, Development, and Information. Baltimore, MD: [Accessed August 18, 2009]. The Medicare care management performance demonstration fact sheet 2007. ( http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/MMA649_Summary.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Measuring Quality, Improving Health. [Accessed August 24, 2009]; ( http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/61/Default.aspx). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jencks SF, Huff ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–1999 to 2000–2001. JAMA. 2003;289:305–312. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medical School Objectives Project (MSOP) of the American Association of Medical Colleges. [Accessed August 24, 2009]; ( https://services.aamc.org/publications/showfile.cfm?file=version87.pdf&prd_id=198&prv_id=239&pdf_id=87). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batalden PB, Stevens DP, Kizer KW. Knowledge for Improvement: Who Will Lead the Learning? Quality Management in Health Care. 2002;10(3):3–9. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edelstein L. The Hippocratic Oath: Text, Translation, and Interpretation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) ACGME Outcome Project. [Accessed August 18, 2009]; Available at ( http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compHome.asp). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shojania KG, Levinson W. Clinicians in quality improvement: a new career pathway in academic medicine. JAMA. 2009;301(7):766–768. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Academic Affiliations. VA Advanced Fellowship Programs. [Accessed August 18, 2009]; Available at ( http://www.va.gov/oaa/specialfellows/default.asp).

- 13.Splaine ME, Aron DA, Dittus RS, Kiefe CI, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, Weeks WB, Batalden PB. A curriculum for training quality scholars to improve the health and health care of veterans and the community at large. Quality Management in Health Care. 2002;10(3):10–18. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware S, et al. Teaching at a distance using interactive video. Journal of Allied Health. 1998;27(3):137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandler G, et al. Teaching using interactive video: Creating connections. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39(2):73–80. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20000201-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogrinc G, Splaine ME, Foster T, Regan-Smith M, Batalden PB. Exploring and embracing complexity in a distance learning curriculum for physicians. Academic Medicine. 2003;8(3):280–285. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindner SA, Davoren JB, Vollmer A, Williams B, Landefeld CS. An electronic medical record intervention increased nursing home advance directive orders and documentation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):1001–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang RL, Donelli A, Byrd J, Mickiewicz MA, Slovis C, Roumie C, Elasy TA, Dittus RS, Speroff T, Disalvo T, Zhao D. Using quality improvement methods to improve door-to-balloon time at an academic medical center. J.Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20(2):46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mooney SE, Ogrinc G, Steadman W. Improving emergency caesarean delivery response times at a rural community hospital. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):60–66. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoover D, Rowe S, Schaub K, Gee J, Pugacz A, Folstad J, Guadelupe K, Yomtovian R, Piña I, Aron D. Getting 'SERIOUS' about medication reconciliation: a model for improving the quality of the medication reconciliation process. Poster presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement National Forum; December 9, 2008; Nashville, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roumie CL, Elasy TA, Greevy R, Griffin MR, Liu X, Stone WJ, Wallston KA, Dittus RS, Alvarez V, Cobb J, Speroff T. Improving blood pressure control through provider education, provider alerts, and patient education: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(3):165–175. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-3-200608010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kern EFO, Beischel S, Stalnaker R, Aron DC, Kirsh SR, Watts SA. Building a diabetes registry from the Veterans Health Administration’s computerized patient record system. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(1):7–14. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Sen S, Bertenthal D, Sands LP, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Covinsky KE, Landefeld CS. The relationship of indwelling urinary catheters to death, length of hospital stay, functional decline, and nursing home admission in hospitalized older medical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinman MA, Rosenthal GE, Landefeld CS, Bertenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ. Conflicts and concordance between measures of medication prescribing quality. Med Care. 2007;45(1):95–99. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241111.11991.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popescu I, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Rosenthal GE. Differences in mortality and use of revascularization in black and white patients with acute MI admitted to hospitals with and without revascularization services. JAMA. 2007;297(22):2489–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.22.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogrinc G, West A, Eliassen MS, Liuw S, Schiffman J, Cochran N. Integrating practice-based learning and improvement into medical student learning: evaluating complex curricular innovations. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):221–229. doi: 10.1080/10401330701364593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster T, Regan-Smith M, Murray C, Dysinger W, Homa K, Johnson LM, Batalden PB. Residency education, preventive medicine, and population health care improvement: the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Leadership Preventive Medicine approach. Acad.Med. 2008;83(4):390–398. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181667da9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon GW, Keitz SA, Holland GJ, Chang BK, Byrne JM, Tomolo A, Aron DC, Wicker AB, Kashner TM. Factors determining medical students' and residents' satisfaction during VA-based training: findings from the VA Learners' Perceptions Survey. Acad.Med. 2008;3(6):611–620. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181722e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is“quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2007;16:2–3. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.022046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawson R, Tlley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage Publications Limited; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes. BMJ. 2007;335:858–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39359.525174.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voelker R. Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars mark 35 years of health services research. JAMA. 2007;297:2571–2573. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.23.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]