Abstract

Males have a higher risk for developing Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism after ischemic stroke than females. Although estrogens have been shown to play a neuroprotective role in Parkinson's disease, there is little information on androgens' actions on dopamine neurons. In this study, we examined the effects of androgens under conditions of oxidative stress to determine whether androgens play a neuroprotective or neurotoxic role in dopamine neuronal function. Mitochondrial function, cell viability, intracellular calcium levels, and mitochondrial calcium influx were examined in response to androgens under both nonoxidative and oxidative stress conditions. Briefly, N27 dopaminergic cells were exposed to the oxidative stressor, hydrogen peroxide, and physiologically relevant levels of testosterone or dihydrotestosterone, applied either before or after oxidative stress exposure. Androgens, alone, increased mitochondrial function via a calcium-dependent mechanism. Androgen pretreatment protected cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death. However, treatment with androgens after the oxidative insult increased cell death, and these effects were, in part, mediated by calcium influx into the mitochondria. Interestingly, the negative effects of androgens were not blocked by either androgen or estrogen receptor antagonists. Instead, a putative membrane-associated androgen receptor was implicated. Overall, our results indicate that androgens are neuroprotective when oxidative stress levels are minimal, but when oxidative stress levels are elevated, androgens exacerbate oxidative stress damage.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by Lewy body formations and motor disturbances, such as bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, and postural instability (1). The loss of dopamine neurons within the substantia nigra pars compacta is one of the primary pathological features of PD (2–6) and has been clearly linked with the motor disturbances associated with PD (7, 8). Dopamine neurons are inherently vulnerable to oxidative stress due to the process of dopamine metabolism, which can generate reactive oxygenated species (ROS) and free radicals (9). Oxidative stress, in turn, has been described as a key factor in the pathogenesis of PD (10–12).

Two clinically known risk factors for PD are aging and gender (9, 13–16). Oxidative stress increases with age (17), and PD incidence increases exponentially in individuals above the age of 65 years (18, 19). Furthermore, aged men have a greater prevalence of PD than aged women (9, 13–16). Interestingly, men also have a higher incidence of parkinsonism after ischemic stroke than women (20, 21), a neurodegenerative condition in which oxidative stress is strongly implicated as an important factor in the progression of cell death (22, 23). Therefore, these studies indicate a potential role for androgens in oxidative stress-mediated neurodegeneration.

The role of androgens, the major male sex hormone, in the higher incidence of PD is unclear. Although androgen levels decrease with age (24), androgen levels continue to remain higher in aged males than females (25). Some studies support a neuroprotective role for androgens, in which androgens can protect against oxidative stress damage (26, 27). A possible mechanism for androgen-induced neuroprotection is preconditioning because androgens alone can moderately increase oxidative stress and apoptosis (28). However, other studies indicate that androgens may not always be neuroprotective. For example, in a preexisting oxidative stress environment, androgens can further exacerbate oxidative stress damage (29). These results suggest that the level of oxidative stress determines whether androgens play a positive or negative role in neuronal function. We propose that below a certain oxidative stress threshold, androgens can be neuroprotective, but once a certain oxidative stress threshold is reached, such as occurs with PD and ischemic stroke, androgens can become damage promoting.

The oxidative stress-associated organelles, mitochondria, serve a variety of metabolic functions within the cell, including a critical role in calcium buffering (30). From a calcium homeostasis point of view, mitochondria can modulate the amplitude and frequency of calcium transients (31, 32), resulting in spontaneous and sustained depolarization of the mitochondria (33). Increased intracellular calcium accumulations have been implicated in the generation of increased oxidative stress (34) and the initiation of cell death in PD (35–38) and ischemic stroke (39, 40). These studies indicate a role for calcium in mediating neuronal vulnerability.

Given the role of oxidative stress in regulating dopaminergic cell fate and the conflicting studies regarding androgens and oxidative stress-mediated neurodegenerative disorders, we examined in the present study whether oxidative stress acts as a molecular switch to define androgen actions on dopamine neurons.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Testosterone (T) propionate, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), flutamide, T-BSA, tert-butyl-hydrogen peroxide, ICI 182,780, and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) were from Sigma. Ruthenium 360 (Ru360) and calcein acetomethoxy (AM) were from Calbiochem. The esterified, membrane-permeant derivative 1-[2-(5-carboxyoxazol-2-yl)-6-aminobenzo furan-5-oxy]-2-(2′-amino-5′-methylphenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, acetoxylmethyl ester Fura-2 AM, RPMI 1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), charcoal-stripped FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, and PBS were purchased from Invitrogen, Molecular Probes. T and DHT were dissolved in ethanol with a final concentration less than 0.0001% ethanol

Cell culture

The rat immortalized mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cell line 1RB3AN27 (N27) was used. This cell line expresses androgen receptor protein (28). The N27 cell line, which is derived from 12-day-old female rat fetal mesencephalic tissue, is composed of immortalized cells positive for tyrosine hydroxylase (41). To confirm the gender origin of the cells used in our study, we used a quantitative real-time PCR method to amplify Sry (sex-determining region Y), a male-specific gene expressed in human and rat embryos (42). Quantitative RT-PCR with rat Sry primers (Taqman Gene expression assay number Rn04224592_u1) detected no expression of this gene in the N27 cells, confirming their female origin. N27 cells were cultured at 5% CO2 at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and subcultured weekly. All experiments were performed between passages 12 and 19 and at approximately 80% confluency in RPMI 1640 medium without serum or with charcoal-stripped FBS to avoid confounders due to the presence of hormones in the serum (28).

Treatment paradigm

For mitochondria membrane potential experiments, N27 cells were incubated for 30 minutes with 10 nM TMRM (mitochondrial membrane potential indicator) (43–45) in serum- and phenol red-free RPMI 1640 prior to exposure to physiologically relevant levels of androgens for 2 hours (46–48). In some experiments, a 30-minute preincubation with the mitochondrial uniporter inhibitor, Ru360 (1uM), was included. Inhibition of the mitochondrial uniporter blocks calcium influx across the inner membrane of the mitochondria (49). For cell viability experiments, cells, incubated in charcoal-stripped FBS, were exposed to hydrogen peroxide (100–250 μM) for 12–14 hours to induce 20%-30% cell loss followed by a 24-hour exposure to androgens, unless stated otherwise. Because subsequent T exposure does not alter cell viability in experiments that have less than 20% oxidative stress-induced cell loss, only experiments in which hydrogen peroxide induced 20%-30% cell loss were examined. Cells were exposed to the various inhibitors 30 minutes prior to androgen exposure. T, DHT, and flutamide were made from a stock solution in ethanol (final concentration of ethanol < 0.001%). Vehicle control-treated cells were exposed to less than 0.001% ethanol.

Mitochondrial membrane potential imaging

Images were collected by a Zeiss confocal microscope with a ×63 oil objective. TMRM was excited at 543 nm and the fluorescence detected beyond a 560-nm-long pass barrier filter. Each scan contained approximately 300 mitochondria. Scans were randomly selected at the 2-hour time point and Z-series images of TMRM-incubated cells were obtained (45). At the conclusion of the experiment, the mitochondrial protonophore p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (10 μM) was used to uncouple the mitochondrial proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane and eliminate membrane potentials (50). To avoid the confounding contribution of background fluorescence, only data sets in which p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone abolished the membrane potential were used for analysis. The level of fluorescence in mitochondria per scan (n = 3 scans) was analyzed with a National Institutes of Health ImageJ program plug-in. This program is based on a modified form of the Nernst equation, which uses the fluorescence measured in individual mitochondria to calculate mitochondrial membrane potentials as follows: where Vmit is the mitochondrial membrane potential; Fmit is the intramitochondrial fluorescence; and Fcyto is the cytosolic fluorescence (51). After analysis, Z-series images were converted to Z-projections to show the population response. The membrane potential can be used as a measure of mitochondrial function because it is also influenced by ATP demand, respiratory chain capacity, proton conductance, substrate availability, and mitochondrial calcium sequestration (52).

Intracellular calcium imaging

Cells were plated on 25-mm microcircle coverglasses at a density of 45 000 cells in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. At 80% confluency, cells were washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). Fura-2 AM was used to determine intracellular free calcium concentration. ([Ca++]i). The ratio of fluorescent intensity at 340 nm excitation (fura-2 AM calcium bound complex) to 380 nm excitation (calcium free fura-2 AM) was used as a measure of intracellular calcium concentration. The emission wavelength was 520 nm. Cells were loaded with 5 μM of fura-2 AM for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2. The cells were washed twice with HBSS to remove excess Fura-2 AM. Fresh HBSS media were added to the cells, and the basal 340/380 nm ratio (R) was measured. Following basal calcium measures, the cells were treated with 100 nM T or vehicle and the 340- and 380-nm measurements were obtained. At the end of the 10-minute experiment, the maximum 340/380 nm ratio was obtained by the addition of 2 μM ionomycin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to the media to stimulate intracellular calcium release and the minimum 340/380 nm ratio was determined after the addition of 500 mM EGTA. Intracellular calcium concentration was estimated from the following equation: [Ca++]i = βKd (R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R), in which Kd is the dissociation constant of fura-2 AM (224 nm under normal conditions), R is any given 340/380 ratio value of fluorescence measured for calcium-free and calcium-bound fura-2 AM, Rmin is the 340/380 ratio in the absence of calcium when the cells are exposed to EGTA, Rmax is the 340/380 ratio when the cells are exposed to ionomycin, and β is the ratio of the fluorescence measured at 380 nm in calcium depleted and calcium saturated (53). Images were captured using NIS-Elements AR 3.0 software on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S microscope, with a ×40 (NA 0.60) objective and a Photometrics Cascade camera. Thirteen cells were analyzed in the T condition, and seven cells were examined in the vehicle condition. All experiments were carried out at room temperature and measured within 15 minutes.

Cell viability

Cells were plated in triplicate into a 96-well black tissue culture plate at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well per experiment. Three independent replications, consisting of three separate plates, were performed for a final n = 3/treatment group. Controls were normalized to 100%. For viability analysis, media were aspirated and replaced with the fluorescent membrane-permeant cell marker, calcein AM (2 mM) in PBS. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Fluorescence was measured in a fluorescent plate reader with the temperature setting at 37°C and the excitation and emission wavelengths at 485 nm and 530 nm, respectively. The intensity of the fluorescence is directly proportional to the number of live cells.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was computed by the IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 software. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance (P ≤ .05) for mitochondrial membrane potentials, and cell viability was determined by ANOVA followed by the Fisher's least significant differences (LSD) post hoc test. Paired t tests were used to determine statistically significant differences between treatment groups in the intracellular calcium analysis experiments.

Results

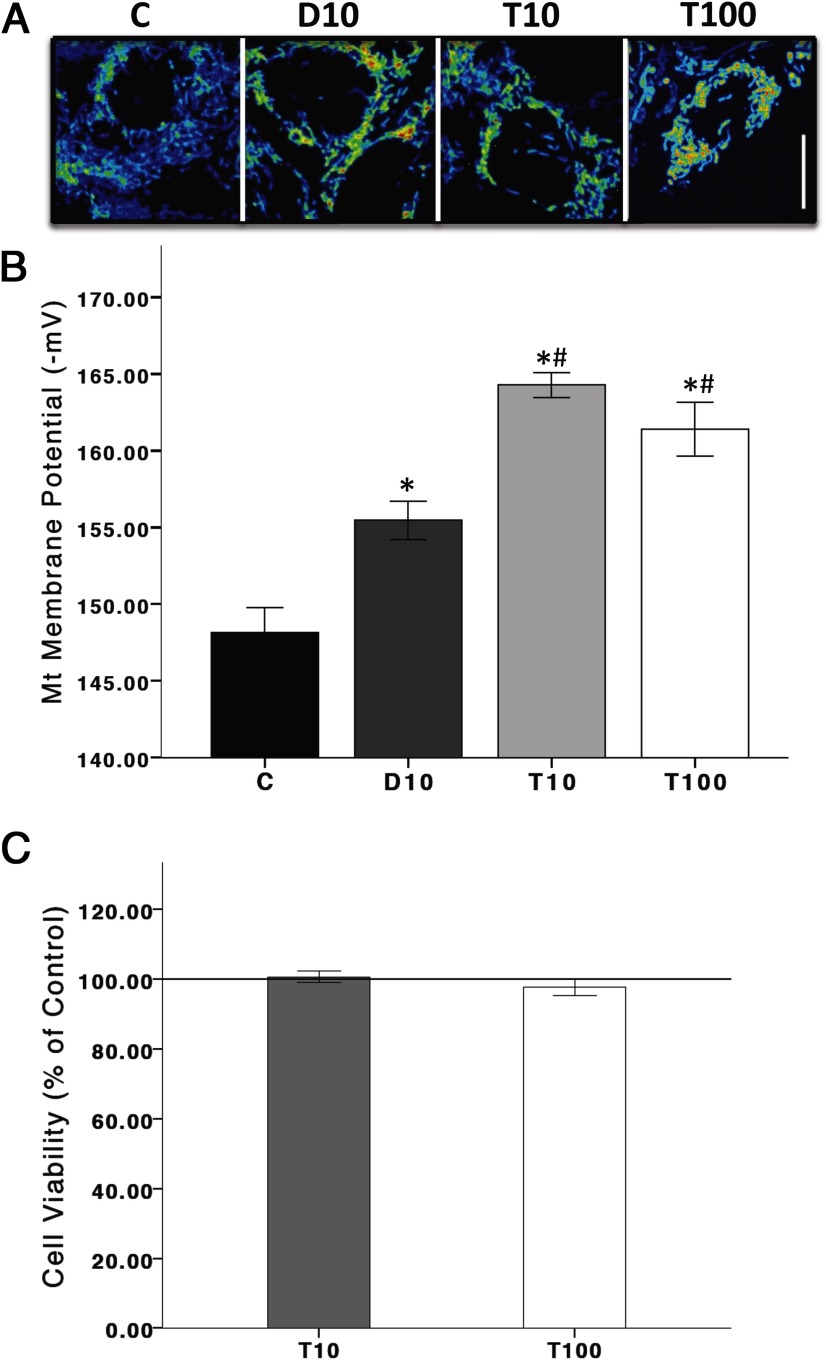

T and DHT alter mitochondrial function in N27 cells

In a recent study, we showed that androgens, possibly through the mitochondria, play a role in dopaminergic function (28). In the current study, mitochondrial function was examined indirectly by measuring mitochondrial membrane potentials. Specifically, cells were incubated in the mitochondrial membrane potential indicator (TMRM, 10 nM) 30 minutes prior to T (10 or 100 nM) or DHT (10 nM) for 2 hours. Figure 1, A and B, shows fluorescent micrographs of dopaminergic N27 cell mitochondria after T and DHT exposure. At 2 hours, T and DHT significantly increased mitochondrial membrane potential activation (derived using a Nernst based equation), as evidenced by the increased fluorescence, compared with vehicle controls (F 3,11 = 25.987, P < .05). These results suggest an underlying androgen-dependent mechanism on mitochondria membrane potential. We have previously shown that androgens, alone, can moderately increase cell death (10%) in N27 cells after 48 hours of exposure (28), but androgens do not have a detrimental effect on cell viability after 24 hours of exposure (Figure 1C) or in conditions that hydrogen peroxide induces less than 20% cell death (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Androgens alter mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial membrane potentials were assayed with the fluorescent dye TMRM. Increased fluorescence is indicative of increased mitochondria membrane potentials. N27 cells were exposed to either T (10 and 100 nM) or DHT (10 nM) for 2 hours (panels A and B). After 2 hours of exposure, T and DHT significantly increased TMRM fluorescence in N27 cells compared with vehicle control. T significantly increased TMRM fluorescence compared with DHT. T exposure for 24 hours did not influence cell viability (panel C). T10, 10 nM T; T100, 100 nM T; D10, 10 nM DHT; C, vehicle control. ANOVA was followed by an LSD post hoc test. Scale bar, 10 μM. * and #, Significance compared with C and D10, respectively. Horizontal line demarcates controls normalized to 100%.

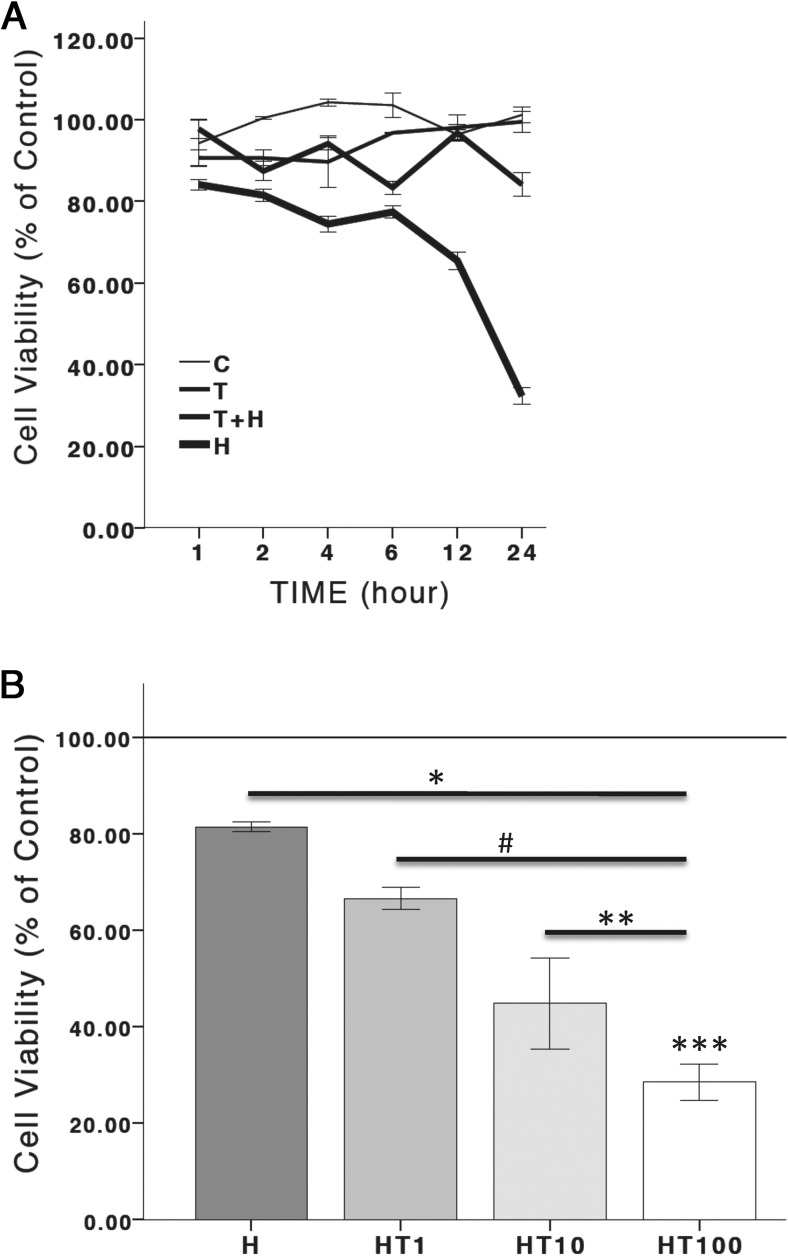

The timing of androgen exposure relative to the induction of oxidative stress determines the neuroprotective or neurotoxic properties of androgens on neuronal function

To determine the role of oxidative stress on androgen-mediated neuronal function, N27 cells were exposed to 100 nM T at the following times: 1) before (2 h) the application of the oxidative stressor, hydrogen peroxide; 2) 12–14 hours after the induction of oxidative stress with hydrogen peroxide; or 3) at the same time as when oxidative stress was induced (ie, coapplication of T and hydrogen peroxide). Figures 2 and 3 depict cell viability measurements. In Figure 2A, ANOVA reveals a significant overall effect of treatment groups (F 3,92 = 203.471, P < .05), time (F 5,92 = 11.505, P < .05), and an interaction between time and treatment groups (F 15,92 = 23.014, P < .05). In Figure 2B ANOVA shows a significant overall effect of treatment groups (F 4,14 = 36.158, P < .05). In Figure 3, A and B, there was a significant effect of treatment groups (F 3,11 = 9.640, P < .05) and (F 5,17 = 4.513, P < .05), respectively.

Figure 2.

Timing of hydrogen peroxide and T. Cell viability is presented as a percentage of control. Hydrogen peroxide significantly decreased cell viability. Two hours of T pretreatment significantly blocked hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death (A). Hydrogen peroxide significantly decreased cell viability. Twenty-four hours of T posttreatment significantly increased hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner (B). H, hydrogen peroxide; T, 100 nM T; T+H, 100 nM T pretreatment; HT, T 100 nM posttreatment; HT1, T 1 nM posttreatment; HT10, T 10 nM posttreatment; HT100, T 100 nM posttreatment; C, vehicle control. An ANOVA was followed by an LSD post hoc test. *, Significant compared with C; #, significant compared with H; **, significant compared with HT1; ***, significant compared with HT10. Horizontal line demarcates controls normalized to 100%.

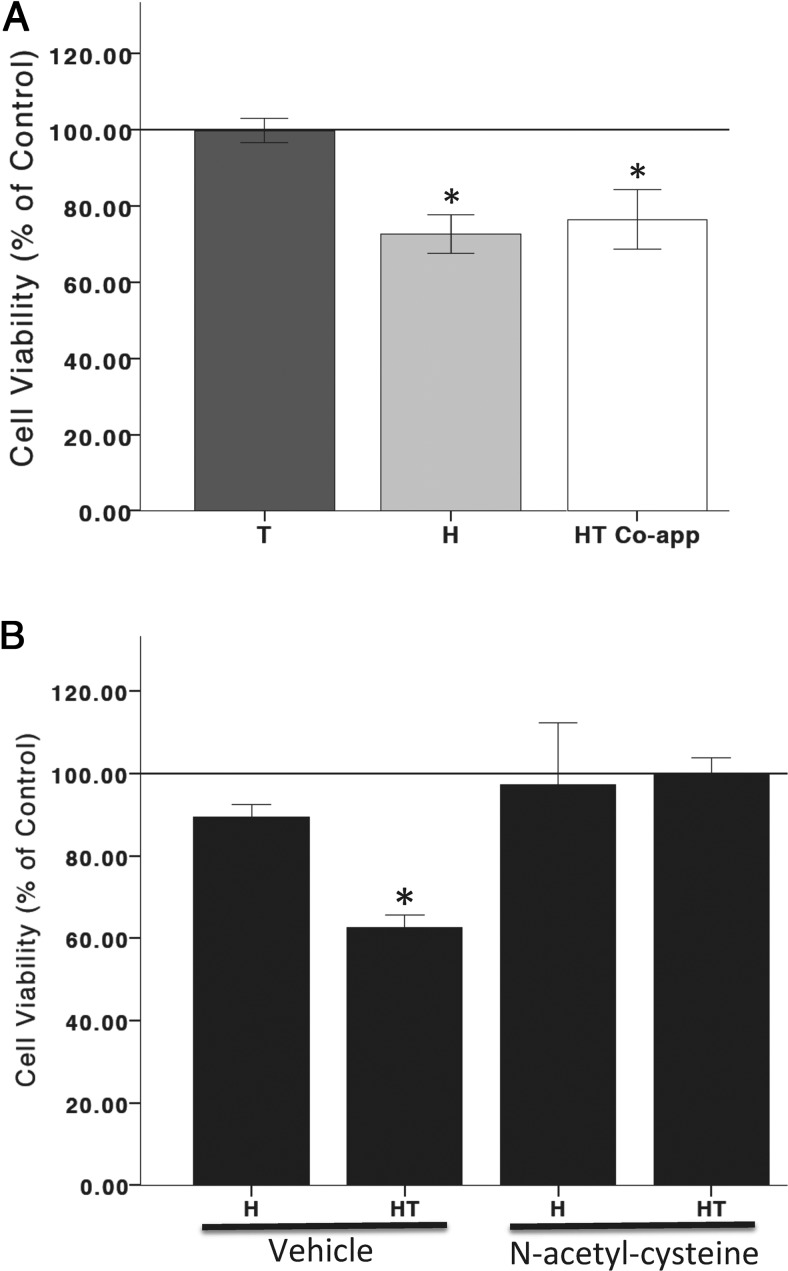

Figure 3.

Oxidative stress and androgen interaction. Hydrogen peroxide significantly increased cell death. T does not alter hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death when coapplied with hydrogen peroxide (A). The antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (1 mM), blocked T posttreatment and hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death (B). C, vehicle control; H, hydrogen peroxide; HT, T 100 nM posttreatment. An ANOVA was followed by an LSD post hoc test. *, Significant compared with C. Horizontal line demarcates controls normalized to 100%.

These results indicate that when cells are pretreated with T (100 nM) for 2 hours prior to oxidative stress, T is neuroprotective against subsequent oxidative stress. Conversely, when cells are pretreated for 12–14 hours with hydrogen peroxide to induce 20%-30% cell loss and then exposed to T for 24 hours, T becomes neurotoxic, as evidenced by a concentration-dependent increase in oxidative stress induced cell death (Figure 2). However, if cells are simultaneously exposed to hydrogen peroxide and T, T does not alter cell viability, indicating that a cellular response to hydrogen peroxide is required for androgens' negative effects on cellular function. Hydrogen peroxide at concentrations that induce 20%-30% cell loss in N27 cells increases ROS generation, and this increase in ROS generation can be blocked by antioxidants (54). To determine whether hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress mediates androgens' deleterious effects on cell viability, the antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (1 mM), was applied to cells at the same time as hydrogen peroxide, 12–14 hours prior to T (100 nM). In the presence of the oxidant species scavenger, N-acetyl-cysteine (55, 56), T did not compromise cell viability. These results indicate the involvement of ROS in androgens' negative effects on cell viability (Figure 3).

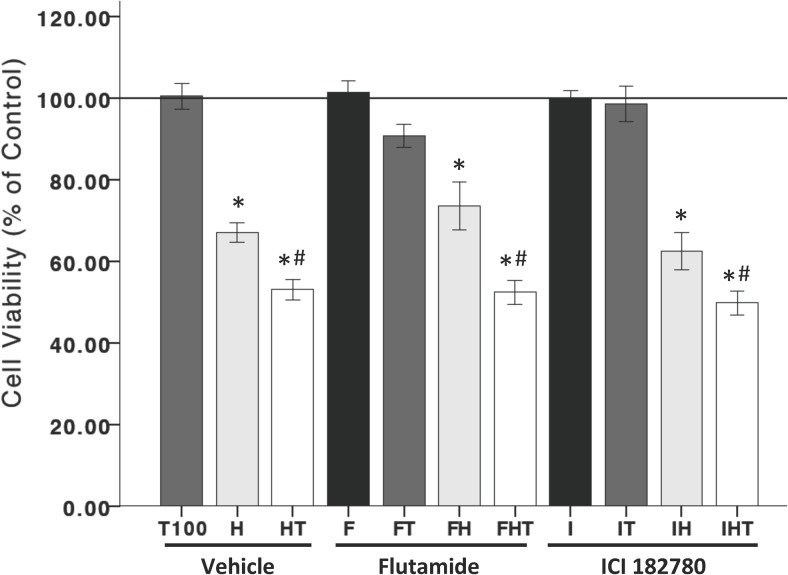

The neurotoxic properties of T are androgen and estrogen receptor independent in N27 cells

The role of androgen and estrogen receptors were examined in the T post-hydrogen peroxide treatment in Figure 4. ANOVA reveals a significant effect of treatment groups (F 11,35 = 35.699, P < .05). Similar to previous results, T (100 nM) after hydrogen peroxide exposure significantly decreased cell viability. This effect was neither blocked by the androgen receptor antagonist, flutamide (500 nM), nor the estrogen receptor-α/β antagonist, ICI 182,780 (1 μM), suggesting that T's neurotoxic effects on cell viability, under conditions of oxidative stress, are independent of T's cognate receptors in N27 cells.

Figure 4.

The deleterious effects of T are not mediated by androgen or estrogen receptors. Neither the androgen receptor nor estrogen-α/β receptors mediate T posttreatment negative effects on cell viability, as evidenced by the lack of effect in response to the androgen receptor antagonist, flutamide (500 nM), and the estrogen receptor-α/β antagonist, ICI 182,780 (1 uM). H, hydrogen peroxide; T, 100 nM T; HT, T posttreatment; C, vehicle control. An ANOVA was followed by an LSD post hoc test. *, Significant compared with C; #, significant compared with H. Horizontal line demarcates controls normalized to 100%.

Intracellular calcium mediates T's negative effects in an oxidative stress environment

Previous studies have shown the ability of T to increase intracellular calcium levels in catecholaminergic SH-SY5Y cells (57). To determine whether T, alone, increases intracellular calcium in N27 cells, nonoxidative stressed, normal cells were bathed in a calcium-free buffer and incubated with the fluorescent calcium sensor dye, FURA-2 AM, to measure [Ca++]i. In the calcium-free buffer, baseline [Ca++]i was 4.5 nM, and T significantly increased [Ca++]I to 250 nM in response to 100 nM T, well below the approximately 500 nM [Ca++]i considered cytotoxic (58). These results suggest that T induces the release of calcium from intracellular calcium stores [paired t(167) = 9.205, P < .05] (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

T and intracellular calcium. Intracellular calcium ([Ca++]i) levels were measured to determine whether androgens induce calcium release from intracellular stores. FURA-2 AM-loaded N27 cells were bathed in a calcium-free HBSS buffer and basal [Ca++]i were determined until stable. One minute after stabilization, cells were treated with vehicle control or T. In the calcium-free buffer, baseline calcium levels were 4.5 nM and T significantly increased [Ca++]i to 250 nM. The addition of 2 uM ionomycin to the media was used to stimulate maximum intracellular calcium release. A paired t test was used for analysis (A). Mitochondrial function in response to Ru360 (1 uM), a mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor, was used to determine whether the androgen-induced effects on mitochondrial function were mediated through calcium influx into the mitochondria. N27 cells were exposed to either T or Ru360 + T for 2 hours. Ru360 significantly blocked the androgen-induced increase in membrane potentials (B). To determine the involvement of mitochondrial calcium influx in the T posttreatment of hydrogen peroxide induced cell death, Ru360 was applied 30 minutes prior to T exposure. Ru360 significantly blocked T-induced cell death in an oxidative stress environment (C). H, hydrogen peroxide; T, 100 nM T; HT, T posttreatment; R, Ru360; RT, Ru360 + T; C, vehicle control. An ANOVA was followed by an LSD post hoc test. *, Significant compared with C; #, significant compared with C and H; **, significant compared with HT. Scale bar, 10 μM. Horizontal line demarcates controls normalized to 100%.

T-induced increase of mitochondrial membrane potential is mediated via calcium influx into the mitochondria

To ascertain whether androgens, alone, induce mitochondrial activation through a calcium-mediated mechanism, cells were pretreated with the mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor, Ru360, which blocks calcium influx into the mitochondria. TMRM-incubated cells were treated with T (100 nM), with or without Ru360 (1 μM) for 2 hours. Ru360 blocked the T-induced increase of mitochondrial membrane potential (F 3,11 = 19.032, P < .05) (Figure 5B). To determine whether mitochondrial calcium influx mediates T's neurotoxic effects in an oxidative stress environment, Ru360 was applied 30 minutes prior to T exposure in hydrogen peroxide-treated cells (Figure 5C). Similar to previous results, T (100 nM) after hydrogen peroxide exposure significantly decreased cell viability. The negative effect of T on cell viability was blocked by the mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor, Ru360 (F 7,23 = 22.752, P < .05), indicating that calcium influx into the mitochondria plays a role in T's neurotoxic effects on cell viability in an oxidative stress environment.

Membrane-associated androgen receptor involvement in T's neurotoxic effects in an oxidative stress environment

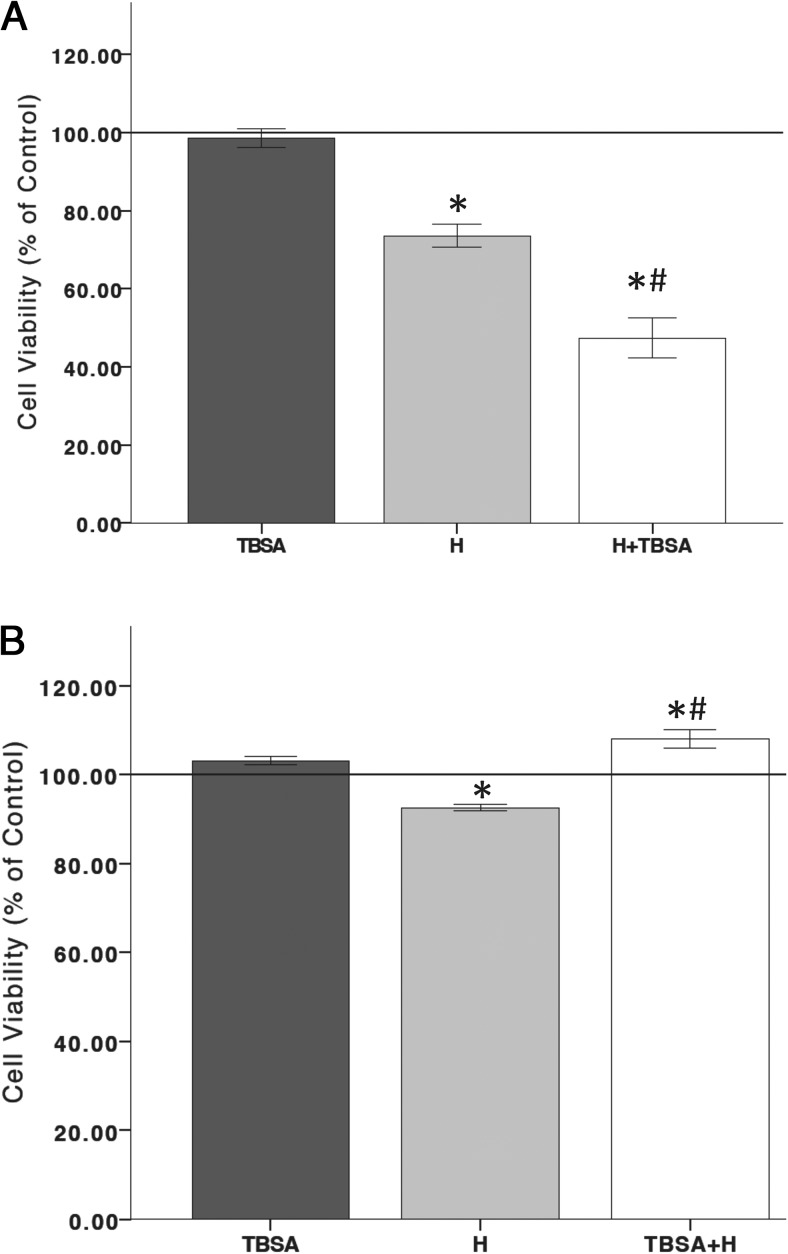

Putative membrane-associated androgen receptors (mAR) have been found in several cell types (59–63). Generally, mAR is indicative of nongenomic signaling because mAR is insensitive to androgen receptor antagonists, such as flutamide, and associated with increased intracellular calcium signaling (61). To determine the involvement of the mAR in the neurotoxic and neuroprotective properties of T in an oxidative stress environment, T conjugated to BSA (TBSA) (500 nM) was used to bind putative mARs on the cell membrane (62). In Figure 6A, an ANOVA revealed a significant overall effect of treatment groups (F 3,11 = 25.683, P < .05), in which TBSA treatment after oxidative stress exposure significantly decreased cell viability. Furthermore, ANOVA showed a significant effect of treatment (F 3,11 = 29.639, P < .05), wherein the TBSA 2-hour pretreatment prior to a 6-hour oxidative stress exposure protected N27 cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death (Figure 6B). Therefore, these results implicate the involvement of mAR.

Figure 6.

Membrane-associated androgen receptor involvement. To examine the role of mARs, TBSA was used to bind only putative membrane androgen receptors. TBSA alone does not affect cell viability. Hydrogen peroxide significantly decreased cell viability. Twenty-four hours TBSA posttreatment significantly increased hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death (A). TBSA pretreatment for 2 hours blocked cell death induced by a 6-hour exposure to hydrogen peroxide (B). H, hydrogen peroxide; TBSA, 500 nM T conjugated to BSA; H+TBSA, TBSA posttreatment; TBSA+H, TBSA pretreatment; C, vehicle control. An ANOVA was followed by an LSD post hoc test. *, Significant compared with C; #, significant compared with H. Horizontal line demarcates controls normalized to 100%.

Discussion

This study shows that the timing of androgens relative to the onset of oxidative stress defines the neuroprotective and neurotoxic properties of androgens in dopaminergic N27 cells. The key findings were that: 1) the effects of T on N27 cell viability is dependent on the oxidant load of the cell (ie, protective when administered prior to the prooxidant insult, hydrogen peroxide, but cytotoxic when administered after a period of hydrogen peroxide exposure; 2) the neurotoxic effects of T are blocked by the mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor, Ru360; and 3) the neurotoxic effects of T appear to be mediated by a receptor other than the classical androgen or estrogen receptors and may be mediated by a putative mAR.

T has been shown to increase brain mitochondrial activity in the rat (64). Similarly, we found that 2 hours of androgen exposure significantly increased mitochondrial membrane potentials. This increase in mitochondrial function is mediated by calcium influx into the mitochondria. Previous studies have shown an association between androgens and calcium. In a catecholaminergic cell line (SH-SY5Y), nanomolar concentrations of T increased intracellular calcium and calcium oscillations within the cytosol (57). These calcium oscillations have been implicated in many cellular activities (65–67). In this study we found that androgens increased cytosolic calcium levels in dopaminergic N27 cells. This increase in intracellular calcium is likely attributed to calcium release from intracellular calcium stores because the buffer in which the cells were incubated did not contain calcium. The increase in cytosolic calcium resulting from exposure to T under normal conditions is below the predicted cytotoxic levels of calcium (∼500 nM) that result in overt cell dysfunction and death (58). Additionally, when calcium influx across the inner membrane of the mitochondria was blocked using the mitochondrial uniporter inhibitor, Ru360, the androgen-induced increase in mitochondrial membrane potentials was inhibited. Similar effects of androgens on the mobilization of intracellular calcium has been demonstrated in other cells, including human prostate cancer cells (68), rat heart myocytes (69), dopaminergic neuroblastomas (57), and macrophages (70).

The role of androgens in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration is unclear. Some studies support a neuroprotective role for androgens, in which androgens can protect against oxidative stress damage (26, 27). A possible mechanism for androgen-induced neuroprotection is preconditioning, in which androgens promote cellular adaptation against subsequent oxidative stress insults. In our previous findings, T exposure for 48 hours induced a low level of apoptosis (10%) and moderately increased oxidative stress in N27 cells (28). Furthermore, in the current study, a 2-hour T exposure was sufficient to increase mitochondrial activity, intracellular calcium release, and calcium influx into the mitochondria. These effects of androgens on oxidative stress, intracellular calcium, and mitochondrial activation may have preconditioned N27 cells to become more resistant to a subsequent oxidative insult, consistent with other studies that found calcium-mediated neuroprotection (71, 72). This cellular preconditioning may be one of the underlying mechanisms involved in the neuroprotective effects of T against oxidative stress damage, as observed in this study and others (26, 27).

It is possible that low levels of T may predispose individuals to neurodegenerative disorders because low T has been linked with oxidative stress-associated neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and ischemic stroke (73–77). A possible mechanism could be a reduction in T-induced preconditioning, leading to greater vulnerability of specific neuronal systems to oxidative stress. However, once oxidative stress reaches levels at or above the threshold that can induce cellular damage, T switches to a damage-promoting hormone by exacerbating oxidative stress-induced damage. As evidenced in this study, if T is applied after a period of increased oxidative load that induces at least 20% cell death, T exacerbates oxidative stress-related damage in a concentration-dependent manner. However, in low oxidative stress conditions that induce less than 20% cell death, T does not impact cell viability. These results indicate that the presence of oxidative stress may act as a molecular switch, converting the neuroprotective effects of T to one that is neurotoxic. Supporting this hypothesis that oxidative stress was a key determinant of T's effect on cell viability, we found that the free radical scavenger, N-acetyl cysteine, and the mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor prevented the cytotoxic effects of T. A possible mechanism is that N-acetyl cysteine and the mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor reset the cellular oxidative stress system so that the effects of subsequent T exposure may be more similar to effects observed in the T pretreatment and concurrent oxidative stress condition, respectively.

This action of oxidative stress as a molecular switch for androgen actions is especially relevant to the debate of treating the elderly with androgens. Recently T replacement therapy (TRT) has been proposed as a neuroprotective therapeutic in aged men to prevent or treat age-related disorders (73, 78, 79). However, results have been equivocal. These equivocal results were of sufficient concern to prompt the National Institutes of Health and the Institute of Medicine to question the value of TRT in elderly men. They concluded that further research is required to determine whether TRT is, in fact, a viable treatment for age-related disorders (80). According to our data, we propose that TRT would be beneficial as a preventative strategy. However, TRT use as a treatment in oxidative stress conditions (ie, PD, ischemic stroke) may exacerbate neuronal damage or in the case of ischemic stroke increase the risk for parkinsonism in men. Furthermore, the physiological state of the patient with respect to oxidative stress levels should be examined prior to TRT to ensure that individuals with high levels of oxidative stress are not exposed because TRT could be damage promoting in this group of individuals.

Mechanisms underlying T's neurotoxic effects could include increased free radical generation and intracellular calcium. T alone increased ROS in N27 cells (28), and the free radical scavenger, N-acetyl cysteine, blocked the deleterious effects of T on cell viability, indicating the involvement of ROS. These results are in agreement with previous studies investigating the contribution of sex differences in mitochondrial dysfunction in which male rats had higher levels of peroxide production, lower mitochondrial glutathione, and increased oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA compared with females (81, 82). Furthermore, human males have higher urinary excretion of 8-hydroxyguanosine (a measure of oxidative damage to DNA) than females (83). Together these observations reinforce the hypothesis of androgen involvement in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress damage.

Another possible mechanism underlying androgen's neurotoxic effects is intracellular calcium. Interestingly, calcium accumulation can be an oxidative stressor per se (84). Furthermore, mitochondrial calcium overload has been implicated in the generation of ROS and in the release of several proapoptotic proteins (85), which may play an important role in the neurotoxic properties of androgens. In addition to free radical generation, excitotoxicity through calcium overload has been implicated in dopaminergic neuronal death (86). In the current study, T increased intracellular calcium concentrations via calcium release from intracellular calcium stores. In an oxidative stress environment, this increase in intracellular calcium can lead to calcium overload and neurotoxicity. Indeed, our results indicate that calcium influx into the mitochondria is one of the contributing factors for T-induced cell loss in an oxidative stress environment. Inhibition of mitochondrial calcium influx blocked T's damage-promoting effects on N27 cells, consistent with other studies that showed neuroprotection in response to mitochondrial calcium inhibition (87–90). Therefore, the observation that aged men have a greater prevalence of PD (9, 13–16) and increased incidence of parkinsonism after ischemic stroke than aged women (20, 21) may be related to the following: 1) the loss of androgen-mediated preconditioning, resulting in increased oxidative stress and 2) androgen-induced calcium overload in the mitochondria, leading to further increases in oxidative stress to induce dopaminergic neurotoxicity.

Interestingly, it does not appear that the classical androgen and estrogen receptors mediate androgen's neurotoxic effects in an oxidative stress environment because this effect was insensitive to androgen and estrogen receptor antagonists. As an alternative, we proposed the potential involvement of a putative mAR. Generally, mAR is indicative of nongenomic signaling because mAR is insensitive to androgen receptor antagonists and associated with increased intracellular calcium signaling (60, 61, 91). Consistent with mAR actions, the neurotoxic properties of T in this study were insensitive to the androgen receptor antagonist, flutamide, and involved increased intracellular signaling. Furthermore, similar to what was observed with T, TBSA, a mAR ligand, significantly decreased cell viability in an oxidative stress environment but in a pretreatment paradigm protected cells from oxidative stress-induced cell loss. Further research in this area needs to be conducted to determine whether manipulation of this nongenomic pathway can provide more effective therapies for oxidative stress-mediated neurodegenerative conditions.

In conclusion, our results indicate that androgens are neuroprotective against subsequent oxidative stress-induced damage, possibly through a preconditioning mechanism. However, in a preexisting high oxidative stress environment, androgens can become neurotoxic and exacerbate oxidative stress damage. Our results offer a mechanism that reconciles the differing effects of androgens in an oxidative stress environment, such as the in vivo studies in male rodents from our laboratory and other laboratories, in which androgens protected against oxidative stress-related insults, such as middle cerebral artery occlusion, β-amyloid, and 3-nitropropionic acid (92–95), and androgens exacerbated damage resulting from oxidative stress-related insults of middle cerebral artery occlusion and 6-hydroxydopamine (29, 96, 97). Furthermore, this study provides further support for the possible role of androgenic mechanisms underlying the greater prevalence of PD (9, 13–16) and increased incidence of parkinsonism after ischemic stroke in men compared with women (20, 21).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Lora Talley-Watts, Dr Andrea Giuffrida, Hai-Ying Ma, Nataliya Rybalchenko, Rosa Lemus, Dr Victoria E. Centonze, Dr James L. Roberts, and Dr James Lechleiter for their technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants F32NS061417–01 and AHA 10BGIA4180116, Garvey Texas Foundation (to R.L.C.); and Grants AG022550 and AG027956 (to M.S.). Images were generated in the Core Optical Imaging Facility supported by University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, National Institutes of Health-National Cancer Institute Grant P30 CA54174 (Cancer Therapy and Research Center at University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio) and National Institutes of Health-NIA Grant P01AG19316.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AM

- acetomethoxy

- [Ca++]i

- intracellular free calcium concentration

- DHT

- dihydrotestosterone

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- LSD

- least significant differences

- mAR

- membrane-associated androgen receptor

- N27

- 1RB3AN27

- PD

- Parkinson's disease

- ROS

- reactive oxygenated species

- Ru360

- Ruthenium 360

- TBSA

- T conjugated to BSA

- TMRM

- tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- TRT

- T replacement therapy.

References

- 1. Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318(1):121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39(6):889–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forno LS. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55(3):259–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Science. 2003;302(5646):819–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dietz V, Quintern J, Berger W. Electrophysiological studies of gait in spasticity and rigidity. Evidence that altered mechanical properties of muscle contribute to hypertonia. Brain. 1981;104(3):431–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shastry BS. Neurodegenerative disorders of protein aggregation. Neurochem Int. 2003;43(1):1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hornykiewicz O. Dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) and brain function. Pharmacol Rev. 1966;18(2):925–964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Riederer P, Wuketich S. Time course of nigrostriatal degeneration in Parkinson's disease. A detailed study of influential factors in human brain amine analysis. J Neural Transm. 1976;38(3–4):277–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lotharius J, Barg S, Wiekop P, Lundberg C, Raymon HK, Brundin P. Effect of mutant α-synuclein on dopamine homeostasis in a new human mesencephalic cell line. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(41):38884–38894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jenner P. Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(suppl 3):S26–S36; discussion S36–S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gille G, Hung ST, Reichmann H, Rausch WD. Oxidative stress to dopaminergic neurons as models of Parkinson's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1018:533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanthasamy AG, Kitazawa M, Kaul S, et al. Proteolytic activation of proapoptotic kinase PKCδ is regulated by overexpression of Bcl-2: implications for oxidative stress and environmental factors in Parkinson's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1010:683–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mayeux R, Marder K, Cote LJ, et al. The frequency of idiopathic Parkinson's disease by age, ethnic group, and sex in northern Manhattan, 1988–1993. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(8):820–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hofman A, Collette HJ, Bartelds AI. Incidence and risk factors of Parkinson's disease in The Netherlands. Neuroepidemiology. 1989;8(6):296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Den Eeden S, Tanner C, Bernstein A, et al. Incidence of Parkinson's disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(11):1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanrott K, Gudmunsen L, O'Neill MJ, Wonnacott S. 6-Hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis is mediated via extracellular auto-oxidation and caspase 3-dependent activation of protein kinase Cδ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(9):5373–5382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366(1–2):211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Lau LM, Giesbergen PC, de Rijk MC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Incidence of parkinsonism and Parkinson disease in a general population: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2004;63(7):1240–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Rijk MC, Tzourio C, Breteler MM, et al. Prevalence of parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease in Europe: the EUROPARKINSON Collaborative Study. European Community Concerted Action on the Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(1):10–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benitez-Rivero S, Marin-Oyaga VA, Garcia-Solis D, et al. Clinical features and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT imaging in vascular parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(2):122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thanvi B, Lo N, Robinson T. Vascular parkinsonism—an important cause of parkinsonism in older people. Age Ageing. 2005;34(2):114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doyle KP, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Mechanisms of ischemic brain damage. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(3):310–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehta SL, Manhas N, Raghubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54(1):34–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hollander M, Koudstaal PJ, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Incidence, risk, and case fatality of first ever stroke in the elderly population. The Rotterdam Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(3):317–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gavrilova N, Lindau ST. Salivary sex hormone measurement in a national, population-based study of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009:gbn028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahlbom E, Grandison L, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Ceccatelli S. Androgen treatment of neonatal rats decreases susceptibility of cerebellar granule neurons to oxidative stress in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(4):1285–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahlbom E, Prins GS, Ceccatelli S. Testosterone protects cerebellar granule cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death through a receptor mediated mechanism. Brain Res. 2001;892(2):255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cunningham RL, Giuffrida A, Roberts JL. Androgens induce dopaminergic neurotoxicity via caspase-3-dependent activation of protein kinase Cδ. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5539–5548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cunningham RL, Macheda T, Watts LT, et al. Androgens exacerbate motor asymmetry in male rats with unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. Horm Behav. 2011;60(5):617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Orth M, Schapira AH. Mitochondria and degenerative disorders. Am J Med Genet. 2001;106(1):27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ichas F, Jouaville LS, Sidash SS, Mazat JP, Holmuhamedov EL. Mitochondrial calcium spiking: a transduction mechanism based on calcium-induced permeability transition involved in cell calcium signalling. FEBS Lett. 1994;348(2):211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jouaville LS, Ichas F, Holmuhamedov EL, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD. Synchronization of calcium waves by mitochondrial substrates in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Nature. 1995;377(6548):438–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ichas F, Jouaville LS, Mazat JP. Mitochondria are excitable organelles capable of generating and conveying electrical and calcium signals. Cell. 1997;89(7):1145–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, et al. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature. 2010;468(7324):696–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan CS, Guzman JN, Ilijic E, et al. 'Rejuvenation' protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1081–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Danzer KM, Haasen D, Karow AR, et al. Different species of α-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J Neurosci. 2007;27(34):9220–9232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, et al. PINK1-associated Parkinson's disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Mol Cell. 2009;33(5):627–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crocker SJ, Smith PD, Jackson-Lewis V, et al. Inhibition of calpains prevents neuronal and behavioral deficits in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23(10):4081–4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Besancon E, Guo S, Lok J, Tymianski M, Lo EH. Beyond NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors: emerging mechanisms for ionic imbalance and cell death in stroke. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(5):268–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kobayashi T, Mori Y. Ca2+ channel antagonists and neuroprotection from cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;363(1):1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adams FS, La Rosa FG, Kumar S, et al. Characterization and transplantation of two neuronal cell lines with dopaminergic properties. Neurochem Res. 1996;21(5):619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miyajima A, Sunouchi M, Mitsunaga K, Yamakoshi Y, Nakazawa K, Usami M. Sexing of postimplantation rat embryos in stored two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) samples by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of an Sry sequence. J Toxicol Sci. 2009;34(6):681–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fall CP, Bennett JP., Jr Visualization of cyclosporin A and Ca2+-sensitive cyclical mitochondrial depolarizations in cell culture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1410(1):77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ward MW, Huber HJ, Weisova P, Dussmann H, Nicholls DG, Prehn JH. Mitochondrial and plasma membrane potential of cultured cerebellar neurons during glutamate-induced necrosis, apoptosis, and tolerance. J Neurosci. 2007;27(31):8238–8249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liang H, Van Remmen H, Frohlich V, Lechleiter J, Richardson A, Ran Q. Gpx4 protects mitochondrial ATP generation against oxidative damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356(4):893–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. World Health Organization, Nieschlag E, Wang C, et al. Guidelines for the Use of Androgens. Heidelberg: Springer; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith KW, Feldman HA, McKinlay JB. Construction and field validation of a self-administered screener for testosterone deficiency (hypogonadism) in ageing men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;53(6):703–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zitzmann M, Brune M, Nieschlag E. Vascular reactivity in hypogonadal men is reduced by androgen substitution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(11):5030–5037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gunter TE, Pfeiffer DR. Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am J Physiol. 1990;258(5 Pt 1):C755–C786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boitier E, Rea R, Duchen MR. Mitochondria exert a negative feedback on the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ waves in rat cortical astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1999;145(4):795–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Loew LM, Tuft RA, Carrington W, Fay FS. Imaging in five dimensions: time-dependent membrane potentials in individual mitochondria. Biophys J. 1993;65(6):2396–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nicholls DG, Budd SL. Mitochondria and neuronal survival. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(1):315–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(6):3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Carvour M, Song C, Kaul S, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy A. Chronic low-dose oxidative stress induces caspase-3-dependent PKCδ proteolytic activation and apoptosis in a cell culture model of dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1139:197–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Moldeus P, Cotgreave IA, Berggren M. Lung protection by a thiol-containing antioxidant: N-acetylcysteine. Respiration. 1986;50(suppl 1):31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6(6):593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Estrada M, Uhlen P, Ehrlich BE. Ca2+ oscillations induced by testosterone enhance neurite outgrowth. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 4):733–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Abramov AY, Duchen MR. Measurements of threshold of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in intact and permeabilized cells by flash photolysis of caged calcium. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;793:299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Figueroa-Valverde L, Luna H, Castillo-Henkel C, Munoz-Garcia O, Morato-Cartagena T, Ceballos-Reyes G. Synthesis and evaluation of the cardiovascular effects of two, membrane impermeant, macromolecular complexes of dextran-testosterone. Steroids. 2002;67(7):611–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kampa M, Nifli AP, Charalampopoulos I, et al. Opposing effects of estradiol- and testosterone-membrane binding sites on T47D breast cancer cell apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307(1):41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kampa M, Papakonstanti EA, Hatzoglou A, Stathopoulos EN, Stournaras C, Castanas E. The human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP bears functional membrane testosterone receptors that increase PSA secretion and modify actin cytoskeleton. FASEB J. 2002;16(11):1429–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gatson JW, Singh M. Activation of a membrane-associated androgen receptor promotes cell death in primary cortical astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):2458–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gatson JW, Kaur P, Singh M. Dihydrotestosterone differentially modulates the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathways through the nuclear and novel membrane androgen receptor in C6 cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147(4):2028–2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Garcia MV, Cabezas JA, Perez-Gonzalez MN. Effects of oestradiol, testosterone and medroxyprogesterone on subcellular fraction marker enzyme activities from rat liver and brain. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1985;80(2):347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Borodinsky LN, Root CM, Cronin JA, Sann SB, Gu X, Spitzer NC. Activity-dependent homeostatic specification of transmitter expression in embryonic neurons. Nature. 2004;429(6991):523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ciccolini F, Collins TJ, Sudhoelter J, Lipp P, Berridge MJ, Bootman MD. Local and global spontaneous calcium events regulate neurite outgrowth and onset of GABAergic phenotype during neural precursor differentiation. J Neurosci. 2003;23(1):103–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Root CM, Velazquez-Ulloa NA, Monsalve GC, Minakova E, Spitzer NC. Embryonically expressed GABA and glutamate drive electrical activity regulating neurotransmitter specification. J Neurosci. 2008;28(18):4777–4784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Steinsapir J, Socci R, Reinach P. Effects of androgen on intracellular calcium of LNCaP cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179(1):90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Koenig H, Fan CC, Goldstone AD, Lu CY, Trout JJ. Polyamines mediate androgenic stimulation of calcium fluxes and membrane transport in rat heart myocytes. Circ Res. 1989;64(3):415–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Benten WP, Guo Z, Krucken J, Wunderlich F. Rapid effects of androgens in macrophages. Steroids. 2004;69(8–9):585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yano S, Tokumitsu H, Soderling TR. Calcium promotes cell survival through CaM-K kinase activation of the protein-kinase-B pathway. Nature. 1998;396(6711):584–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hu SC, Chrivia J, Ghosh A. Regulation of CBP-mediated transcription by neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron. 1999;22(4):799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pike CJ, Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Barron AM. Protective actions of sex steroid hormones in Alzheimer's disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30(2):239–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pike CJ, Rosario ER, Nguyen TV. Androgens, aging, and Alzheimer's disease. Endocrine. 2006;29(2):233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jeppesen LL, Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS, Winther K. Decreased serum testosterone in men with acute ischemic stroke. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(6):749–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Harman SM, Tsitouras PD. Reproductive hormones in aging men. I. Measurement of sex steroids, basal luteinizing hormone, and Leydig cell response to human chorionic gonadotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;51(1):35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Okun MS, DeLong MR, Hanfelt J, Gearing M, Levey A. Plasma testosterone levels in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Neurology. 2004;62(3):411–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Morales A, Johnston B, Heaton JP, Lundie M. Testosterone supplementation for hypogonadal impotence: assessment of biochemical measures and therapeutic outcomes. J Urol. 1997;157(3):849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mitchell E, Thomas D, Burnet R. Testosterone improves motor function in Parkinson's disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13(1):133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 81. Borras C, Sastre J, Garcia-Sala D, Lloret A, Pallardo FV, Vina J. Mitochondria from females exhibit higher antioxidant gene expression and lower oxidative damage than males. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34(5):546–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Guevara R, Santandreu FM, Valle A, Gianotti M, Oliver J, Roca P. Sex-dependent differences in aged rat brain mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(2):169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Loft S, Vistisen K, Ewertz M, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Poulsen HE. Oxidative DNA damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine excretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13(12):2241–2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Toescu EC, Myronova N, Verkhratsky A. Age-related structural and functional changes of brain mitochondria. Cell Calcium. 2000;28(5–6):329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fiskum G. Mitochondrial participation in ischemic and traumatic neural cell death. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(10):843–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Beal MF. Excitotoxicity and nitric oxide in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(3 suppl 1):S110–S114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Jambrina E, Alonso R, Alcalde M, et al. Calcium influx through receptor-operated channel induces mitochondria-triggered paraptotic cell death. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):14134–14145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial membrane potential and the permeability transition in excitotoxicity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;893:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Bae JH, Park JW, Kwon TK. Ruthenium red, inhibitor of mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, inhibits curcumin-induced apoptosis via the prevention of intracellular Ca2+ depletion and cytochrome c release. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303(4):1073–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lee WT, Yin HS, Shen YZ. The mechanisms of neuronal death produced by mitochondrial toxin 3-nitropropionic acid: the roles of N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors and mitochondrial calcium overload. Neuroscience. 2002;112(3):707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Papakonstanti EA, Kampa M, Castanas E, Stournaras C. A rapid, nongenomic, signaling pathway regulates the actin reorganization induced by activation of membrane testosterone receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(5):870–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Uchida M, Palmateer JM, Herson PS, DeVries AC, Cheng J, Hurn PD. Dose-dependent effects of androgens on outcome after focal cerebral ischemia in adult male mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(8):1454–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tunez I, Feijoo M, Collado JA, et al. Effect of testosterone on oxidative stress and cell damage induced by 3-nitropropionic acid in striatum of ovariectomized rats. Life Sci. 2007;80(13):1221–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ramsden M, Nyborg AC, Murphy MP, et al. Androgens modulate β-amyloid levels in male rat brain. J Neurochem. 2003;87(4):1052–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Rosario ER, Carroll JC, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Pike CJ. Androgens regulate the development of neuropathology in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26(51):13384–13389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Yang SH, Perez E, Cutright J, et al. Testosterone increases neurotoxicity of glutamate in vitro and ischemia-reperfusion injury in an animal model. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(1):195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hawk T, Zhang YQ, Rajakumar G, Day AL, Simpkins JW. Testosterone increases and estradiol decreases middle cerebral artery occlusion lesion size in male rats. Brain Res. 1998;796(1–2):296–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]