Abstract

Recent work has led to the hypothesis that kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in the arcuate nucleus play a key role in GnRH pulse generation, with kisspeptin driving GnRH release and neurokinin B (NKB) and dynorphin acting as start and stop signals, respectively. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by determining the actions, if any, of four neurotransmitters found in KNDy neurons (kisspeptin, NKB, dynorphin, and glutamate) on episodic LH secretion using local administration of agonists and antagonists to receptors for these transmitters in ovariectomized ewes. We also obtained evidence that GnRH-containing afferents contact KNDy neurons, so we tested the role of two components of these afferents: GnRH and orphanin-FQ. Microimplants of a Kiss1r antagonist briefly inhibited LH pulses and microinjections of 2 nmol of this antagonist produced a modest transitory decrease in LH pulse frequency. An antagonist to the NKB receptor also decreased LH pulse frequency, whereas NKB and an antagonist to the receptor for dynorphin both increased pulse frequency. In contrast, antagonists to GnRH receptors, orphanin-FQ receptors, and the N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor had no effect on episodic LH secretion. We thus conclude that the KNDy neuropeptides act in the arcuate nucleus to control episodic GnRH secretion in the ewe, but afferent input from GnRH neurons to this area does not. These data support the proposed roles for NKB and dynorphin within the KNDy neural network and raise the possibility that kisspeptin contributes to the control of GnRH pulse frequency in addition to its established role as an output signal from KNDy neurons that drives GnRH pulses.

GnRH secretion into the hypophysial portal circulation is the final common pathway for the neural control of LH. Under most endocrine conditions, GnRH secretion occurs episodically (1), a pattern that is essential for normal reproductive function as exposure of gonadotropes to continuous GnRH inhibits LH secretion (2). Clearly the GnRH neurons responsible for this episodic pattern must release GnRH in synchrony, but the mechanisms responsible for synchronizing their activity remain largely unknown. There is evidence from immortalized GnRH cells (3, 4) and primary cultures of immature GnRH neurons (5) that GnRH neurons have the inherent capacity to produce episodic release, but the applicability of these observations to normal adults in which GnRH neurons are anatomically scattered is unclear. Moreover, because kisspeptin is essential for GnRH secretion in humans (6, 7), pulsatile GnRH secretion is normally dependent on some afferent input.

Recently four groups have proposed an important role for a specific set of neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) in synchronizing GnRH release (8–11). These neurons coexpress kisspeptin, neurokinin B (NKB), and dynorphin (12). They are thus called kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons (8) and are found in sheep (12), rats (13, 14), mice (10), and goats (9). There is also evidence that KNDy neurons are important for reproductive function in women (15), although their role in men has been questioned (16). Although this population of neurons was first identified based on the colocalization of these three neuropeptides, most also contain glutamate in mice (17) and sheep (18), whereas galanin and a marker for γ-aminobutyric acid have been observed in a smaller percentage of murine KNDy neurons (17, 19).

Four lines of indirect evidence led to the hypothesis that KNDy neurons were important for episodic GnRH secretion: 1) both kisspeptin (6, 7) and NKB (20) are critical for normal GnRH secretion in humans; 2) KNDy neurons form an interconnected network (13, 21, 22) that includes connections between the ARC on both sides of the third ventricle (22, 23), 3) KNDy neurons contain NK3R, the receptor for NKB (10, 13, 24), and 4) bursts of multiunit electrical activity (MUA) that correlate with LH pulses are recorded from the vicinity of KNDy neurons (25) and are synchronized between each ARC (23). These four groups all proposed that kisspeptin is the output to GnRH neurons, whereas NKB acts within the KNDy network to initiate each GnRH pulse, and dynorphin acts within this network to inhibit KNDy neural activity and thus terminate each pulse. There is strong evidence that kisspeptin is critical for episodic GnRH release (26) and Kiss1r antagonists block LH pulses in ovariectomized (OVX) ewes (27). The proposed actions of NKB are supported by reports that the stimulatory actions of an NK3R agonist, senktide, on GnRH secretion are mediated by kisspeptin release from KNDy neurons in several species (28–33) and that intracerebroventricular (icv) administration of NKB accelerated the frequency of MUA in the ARC of OVX goats (9). There is less evidence for the proposed role of dynorphin, but iv administration of a nonspecific endogenous opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone, prolonged each GnRH pulse in OVX ewes (34), and icv administration of the κ-opioid receptor antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (BNI), increased the frequency of MUA in OVX goats (9).

Although there is thus significant indirect evidence for the hypothesis that KNDy neurons are important to GnRH pulse generation, there is no direct evidence that kisspeptin, NKB, and/or dynorphin act in the ovine ARC to affect endogenous GnRH secretion. Thus the primary goal of this work was to determine what, if any, actions the four established transmitters in KNDy neurons (kisspeptin, NKB, dynorphin, and glutamate) have within the ARC. Specifically, we tested the hypotheses that kisspeptin, NKB, or glutamate act in the ARC to stimulate LH pulse frequency, but dynorphin acts there to inhibit this system. Our approach was to monitor episodic LH secretion, as an index of GnRH release, before and after microimplantation (35, 36) or microinjection (36, 37) of receptor agonists and antagonists into the ARC of OVX ewes. In light of evidence that a GnRH receptor antagonist can increase GnRH pulse frequency in ewes (38) and GnRH directly inhibits neurons in the rodent ARC (39), we also explored a possible role for GnRH neural input to KNDy neurons. We first determined that GnRH-containing varicosities contacted KNDy cell bodies, and then tested the hypotheses that GnRH or orphanin-FQ, an inhibitory endogenous opioid peptide found in GnRH neurons (40), act in the ARC to inhibit LH pulse frequency.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult mixed-breed blackface ewes were maintained in an open barn and moved indoors 3–7 days prior to surgeries. Ewes were fed a maintenance pelleted ration once per day and had free access to water and mineral blocks. Lights were adjusted bimonthly to mimic the duration of natural lighting. All experiments were carried out in ewes that had been OVX for at least 2 weeks, but not more than 10 weeks, prior to any treatments. Surgeries were carried out as previously described (35, 41) under sterile conditions using 2%-4% isofluorane as anesthesia. Ovariectomies were performed via midventral lapaoratomy and chronic bilateral guide tubes were placed just above the ARC (35). Animals were treated with dexamethasone, analgesic, and penicillin, from 1 day before to 5 days after surgery (41). Blood samples (3–4 mL) were collected by jugular venipuncture into heparinized tubes and plasma stored at −20°C. All procedures were approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed National Institutes of Health guidelines for use of animals in research.

Drug and hormone administration

Agonists to NK3R (NKB and senktide) and antagonists to NK3R (SB222200), κ-opioid receptors (BNI), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (MK-801), and orphanin-FQ receptors (UFP-101) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience. The antagonist to Kiss1r, p271, which inhibits LH secretion when given icv to OVX ewes (37) was prepared by Dr R. Millar, and the GnRH receptor antagonist, acyline, was a gift from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Crystalline drugs were stored at either −20°C or room temperature based on the manufacturer's recommendations. Microimplants were cut to either extend 1 mm beyond the end of the guide tube (experiment 1) or to the tip of the guide tube (other experiments). The lumen of microimplants was filled by tamping sterile 22-gauge tubing in crystalline drug at least 60 times (35) and then cleaning the outside with sterile gauze. For microinjections of Kiss1r antagonist (experiments 3 and 4), stock solution (26.4 mg/mL or 0.011 mmol/mL, stored at −20°C) was diluted on the day of the experiment in sterile saline and 150 nL rapidly injected (over 30 sec) into each hemisphere using sterile 1 μL Hamilton syringes with fixed needles that extended to the tip of the guide tube.

Tissue collection

Hypothalamic tissue was collected for immunocytochemistry and histological determination of treatment sites as previously described (37). Briefly, ewes were heparinized and killed with an iv overdose of sodium pentobarbital (8–12 mL Euthasol; Webster Veterinary). When breathing stopped, the head was removed and perfused via internal carotids with 6 L of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 10 U/mL heparin and 0.1% NaNO3. Tissue blocks were removed and stored at 4°C in fixative overnight and then in 30% sucrose. After sucrose infiltration, 45-μm-thick frozen coronal sections were cut using a freezing microtome. For most experiments, every fifth section through the ARC was stained with cresyl violet and examined to determine site of treatment. For immunocytochemistry, 12 parallel series of sections (540 μm apart) were stored at −20°C in cryoprotectant.

Animal experiments

General protocols

Tissues for analysis of GnRH inputs to KNDy neurons were collected during an artificial follicular phase (42). Briefly, OVX ewes (n = 3) were treated with one 0.5-cm-long estradiol implant and two controlled internal drug release progesterone implants for 10–11 days. One day after controlled internal drug release progesterone implant removal, four 3-cm-long estradiol implants were inserted sc to simulate the preovulatory estradiol rise and tissue collected 18 hours later as described above.

Experiments examining the effects of receptor agonists and antagonists were performed in OVX ewes over a 3-year period, and although the general protocol remained the same, minor details evolved. During the first year (experiments 1–3), blood samples were collected every 12 minutes for 2 hours before to 4 hours after insertion of microimplants or microinjections. Thereafter (experiments 4 and 5), blood samples were collected every 10 minutes for 3 hours before to 4 hours after insertion of microimplants or microinjections. At the end of blood sampling, microimplants were removed and animals were given an im injection of 4 mL Gentamicin (Webster Veterinary Supplies) prophylactically. For each experiment, all ewes received all treatments (including controls) with treatment order randomized among the animals in that experiment. There was no effect of order of treatment in any experiment. In most cases, experiments were performed in the breeding season (mid-September through the end of December), but two experiments were done in early anestrus (March through April). Clear LH pulses are evident in OVX ewes throughout the year, but LH pulse frequencies are slightly higher in December than July (43). Because the experimental design used each animal as its own control, this seasonal variation did not affect the analyses.

Experiment 1: does endogenous kisspeptin act in the ARC to control LH pulses?

Ewes from a previous study that had guide tubes targeting the ARC to test the effects of RU486 in OVX ewes treated with estradiol and progesterone (35) were used in this experiment. After the last RU486 treatment in February, the peripheral estradiol and progesterone implants were removed, and the animals allowed to recover for 3 weeks. In early March, the effects of empty (control) or Kiss1r antagonist (p271)-filled microimplants that extended 1 mm beyond the end of the guide tubes were determined using a crossover design (n = 4) with 4 days between treatments.

Experiment 2: does endogenous NKB act in the ARC to control LH pulses?

Another group of ewes from the RU486 study (35) was used in this experiment. After the last RU486 treatment in September, the peripheral implants were removed, and the animals were allowed to recover for 6 weeks. In November, the effects of empty (control) or SB222200-filled microimplants that extended just to the end of the guide tubes were determined using a crossover design (n = 7) with 7 days between replicates.

Experiment 3: what is the effect of a low dose of Kiss1r antagonist in the ARC?

In mid-December, the animals (n = 7) used in experiment 2 received either bilateral microinjections of 500 pmol of p271 per side or 150 nL saline (as controls), and LH pulses were monitored for 2 hours before and 4 hours after injection (this volume was chosen based on preliminary data indicating that control 200 nL injections into the ARC inhibited LH pulses). Treatments were then repeated using a crossover design 3 days later.

Experiment 4: what is the effect of a higher dose of Kiss1r antagonist in the ARC?

Experiment 3 was replicated the next breeding season (October) in a new group of OVX ewes (n = 6) with 2 nmol of p271 or vehicle per side and samples collected every 10 minutes for 3 hours before and 4 hours after microinjection using a crossover design with 6 days between treatments.

Experiment 5: what are the actions of KNDy neurotransmitters, GnRH, and orphanin-FQ in the ARC?

This experiment tested the local effects of NKB, BNI (κ-opioid receptor antagonist), acyline (GnRH receptor antagonist), UFP-101 (orphanin-FQ receptor antagonist), or MK-801 (NMDA receptor antagonist) using microimplants into the ARC. Three sets of OVX ewes were used in this experiment, which took place over the period of a year. The first set (n = 6) received NKB, BNI, and control treatments in September, but only four of these had correct placements. Therefore, two more replicates were done; the next set (n = 7) received BNI, acyline, MK-801, and control treatments in April, whereas the last set (n = 6) received senktide (as part of a different experiment presented elsewhere), NKB, UFP-101, and control treatments in September. There were 4–7 days between replicates in each set.

Immunocytochemistry for kisspeptin, GnRH, and synaptophysin

Triple-label immunofluorescence was conducted on tissue sections from the middle ARC for kisspeptin, GnRH, and synaptophysin (a marker for presynaptic terminals), as previously described (12). Briefly, to visualize kisspeptin and GnRH, tissue sections were coincubated in monoclonal mouse anti-GnRH serum (1:8000; Covance) and polyclonal rabbit antikisspeptin-10 serum (1:200 000; gift from A. Caraty, Université Tours, Nouzilly France) for 17 hours. Kisspeptin was visualized with Alexa 555 goat antirabbit (1:100; 30 min; Invitrogen). Next, GnRH was visualized using biotinylated goat antimouse (1:250: 1 h; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), ABC (1:500; Vector Laboratories), biotinylated tyramide (TSA; 1:250; diluted in PBS with 1 μL of 3% H2O2 per milliliter of total volume; 10 min; PerkinElmer Life Sciences; catalog number NEL700A), and Alexa 488-conjugated streptavidin (1:100; 30 min; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Next, sections were incubated with monoclonal mouse antisynaptophysin (1:200; Sigma; incubated for 17 h) and Cy5-conjugated goat antimouse (1:100; 30 min; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Sections were mounted on gelatinized slides, dried, and coverslipped with gelvatol. Specificity and validation of these antibodies in sheep tissues has been previously described (12, 44). Additional controls included omission of one of the primary antibodies from the protocol; this resulted in complete elimination of labeling for the corresponding antigen without any effect on the others.

Data analyses

Confocal analysis

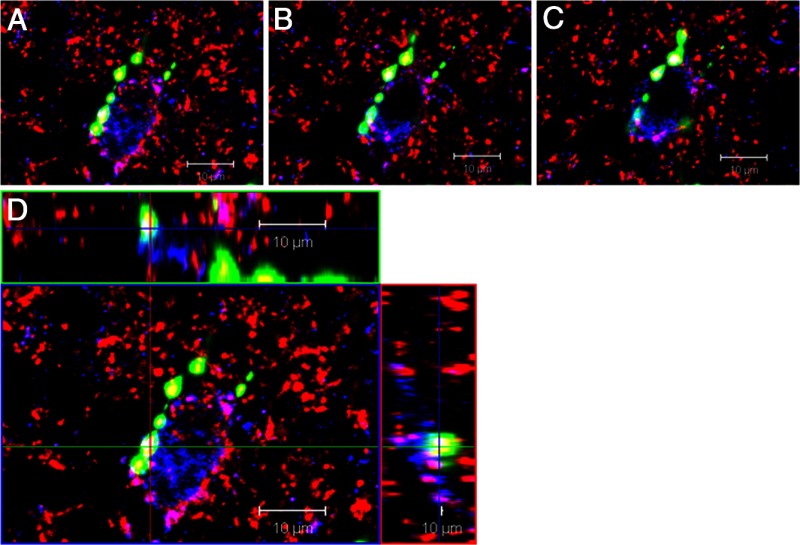

Using a Zeiss LSM-510 laser-scanning confocal microscope system, images of the ARC of the hypothalamus were captured in Z-stacks of 1 μm optical sections. Alexa 555 fluorescence (kisspeptin) was imaged with a HeNe1 laser and a 543-nm emission filter, Alexa 488 fluorescence (GnRH) with an Argon laser and a 488-nm emission filter, and Cy5 fluorescence (synaptophysin) with a HeNe2 laser and a 633-nm emission filter. KNDy cells (30–54/ewe) in hemisections (4–5/ewe) from the middle ARC were analyzed for contacts containing GnRH and synaptophysin. Images were pseudocolored showing kisspeptin in blue, GnRH in green, and synaptophysin in red to optimally illustrate GnRH close appositions onto kisspeptin neurons.

Assays

LH concentrations were measured as previously described in duplicate with a RIA using 100 μL of plasma and reagents provided by the National Hormone and Peptide Program. LH assay sensitivity averaged 0.07 ng/tube (NIH S24) with intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of 5.5% and 11.2%, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Pulses were identified using established criteria (37, 45) and average LH concentration, LH pulse amplitude (AMPL), and interpulse interval (IPI) determined for the following periods: pretreatment (2 or 3 h, depending on experiment), 0–2 hours, and 2–4 hours after insertion of microimplants or microinjections. These values for each experiment were analyzed for differences between agonist/antagonist and control treatments using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (main effects of time and treatment) with Bonferroni's t test used to determine differences between individual values. If a drug increased IPI beyond 2 hours, this analysis would underestimate drug effects. Therefore, in these cases, the maximum duration between two pulses before treatment was compared with this variable during treatment using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. P < .05 was statistically significant.

Results

Analysis of GnRH input to KNDy neurons

In the three animals examined, a total of 133 kisspeptin cells were analyzed and 16.7% ± 4.5% of these were contacted by at least one GnRH/synaptophysin-positive terminal. GnRH terminals were observed in contact with both kisspeptin cell bodies (Figure 3) and dendrites. Synaptophysin was colocalized in all GnRH varicosities in close apposition to KNDy cells, confirming their identity as presynaptic terminals. Kisspeptin cells bearing GnRH inputs were not located in any specific region within the middle ARC but instead were evenly distributed throughout the cell group at this level. To facilitate a concise description, the results of the rest of the experiments have been grouped based on the neurotransmitter being tested, rather than chronologically.

Figure 3.

Close contacts between a GnRH fiber and a KNDy neuron. An example of serial optical sections in a confocal Z-stack (A–C) and orthogonal views (D) through a kisspeptin-positive neuron (blue) receiving close contacts from a GnRH fiber (green) containing varicosities that are colabeled with synaptophysin (red). In addition, numerous dual-labeled kisspeptin/synaptophysin (magenta) inputs also surround this cell, representing KNDy-KNDy reciprocal contacts.

Sites of microimplantation and microinjection

Based on previous evidence on the spread of drugs from similar treatments (37, 46), the microimplant or microinjection sites on both sides of the hypothalamus had to be within 1 mm of the ARC to be considered a correct placement. Using this criterion 28 of 36 ewes were accepted for analysis of LH data, with sites concentrated just before or above the start of the infundibular recess in the anterior-posterior axis (Supplemental Figure 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Missed injections were either dorsal (n = 3), through the base of the hypothalamus (n = 2), in the third ventricle (n = 2), or posterior to the ARC in the mammillary body (n = 1).

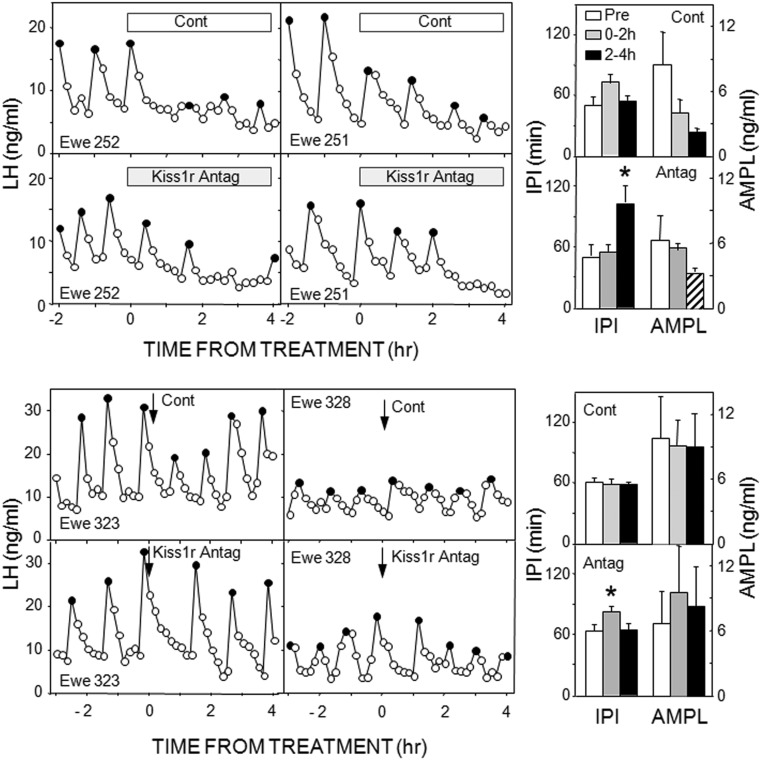

Effects of Kiss1r antagonist

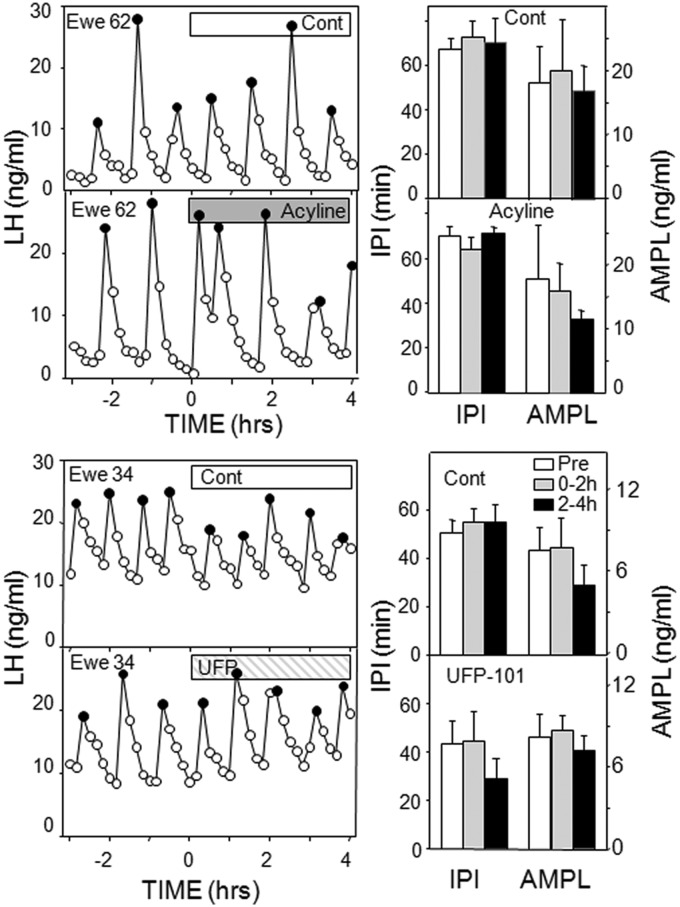

In experiment 1, microimplants containing p271 that extended beyond the guide tubes into the ARC inhibited LH pulses after a delay of 1–2 hours in three of four ewes and significantly increased IPI (Figure 1) and the maximum time between pulses (before: 51 ± 11 min; after: 117 ± 15 min). However, there was also an inhibition of LH concentrations with control treatments (Table 1). This was primarily due to a decrease in LH pulse amplitude (Figure 1), although this was not statistically significant (P = .075); amplitude was not analyzed with the antagonist treatment because three animals had no LH pulses in the final 2 hours of treatment. Because of the effects of control treatment in this experiment, we next tested the effects of placement of empty microimplants to the tip the guide tube (instead of beyond it into tissue). This treatment had no effect on episodic LH secretion (data not shown, but evident in subsequent control treatments), so in all subsequent experiments, microimplants and needles for microinjections were lowered to the tip of the guide tubes.

Figure 1.

Left panels, Top panels depict LH pulse patterns in two ewes receiving empty (open bar) and Kiss1r antagonist-containing (shaded bar) microimplants into the ARC. Bottom panels present LH pulse patterns in two ewes receiving microinjections (arrows) of saline (Cont) and 2 nmol Kiss1r antagonist into the ARC. Solid circles depict peaks of identified LH pulses. Right panels, Mean (± SEM) LH IPIs (left) and AMPLs (right) in response to control and Kiss1r antagonist treatments into the ARC; top two panels are from microimplants and bottom two from microinjections. Open bars, Pretreatment values; shaded bars, values for 0–2 hours after microimplantation or microinjection; black bars, values for 2–4 hours after microimplantation or microinjection; striped bar, not analyzed due to low animal numbers. *, P < .05 vs pretreatment values.

Table 1.

Effect of Treatments on Mean LH Concentrations

| Treatment | Control |

Agonist/Antagonist |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After 0–2 Hours | After 2–4 Hours | Before | After 0–2 Hours | After 2–4 Hours | |

| p271 microimplant | 8.4 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 0.4a | 6.8 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.7a |

| p271 2 nmol | 8.5 ± 2.3 | 9.0 ± 1.4 | 9.8 ± 2.1 | 9.8 ± 1.4 | 9.7 ± 1.6 | 10.1 ± 0.9 |

| SB222200 | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 13.7 ± 3.9 | 12.3 ± 3.8 | 12.5 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 2.3 | 9.1 ± 2.3a |

| NKB | 9.1 ± 1.5 | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 8.9 ± 1.4 | 10.5 ± 0.8 | 11.5 ± 1.4 | 9.6 ± 1.6 |

| BNI | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 9.0 ± 1.4 | 8.3 ± 1.0 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 10.3 ± 1.3 | 9.8 ± 1.6 |

| MK-801 | 6.6 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 2.6 | 8.2 ± 1.7 | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 9.6 ± 2.1 | 9.9 ± 2.4 |

| Acyline | 6.6 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 2.6 | 8.2 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| UFP101 | 10.9 ± 2.1 | 11.5 ± 1.4 | 11.2 ± 1.3 | 10.3 ± 1.0 | 12.1 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.3 |

Data presented are mean (±SEM) for time periods before and 0–2 and 2–4 hours after start of treatments. All treatments were via microimplants, except for 2 nmol of p271, which were administered by microinjections.

P < .05 vs control (before treatment) values by two-way ANOVA.

The next two experiments tested the effects of two doses of this Kiss1r antagonist administered by microinjection. The lower dose (500 pmol/side) was ineffective (Supplemental Table 1), but the higher dose (2 nmol/side) produced a modest increase in IPI just after injection (Figure 1). This effect was consistently seen when all ewes were treated with antagonist, so that IPI after the microinjection were 141% ± 13% longer than the preinjection average (compared with 96% ± 10% with control microinjection). Neither dose significantly altered LH pulse amplitude (Figure 1) or mean LH concentrations (Table 1).

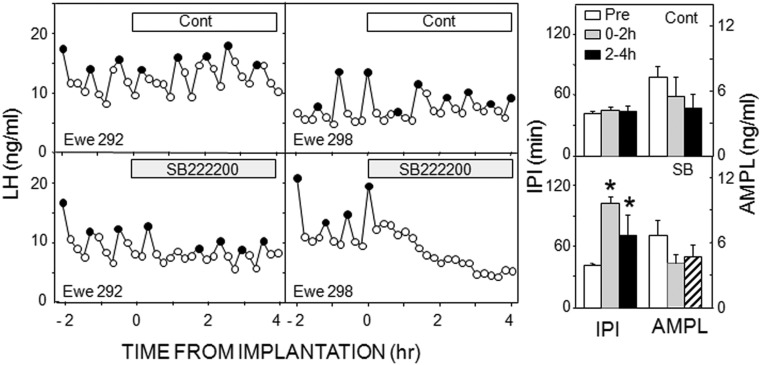

Effects of NK3R antagonist

Treatment of OVX ewes with the NK3R antagonist, SB222200, disrupted episodic LH secretion in all five ewes and significantly increased IPI, whereas there was no effect of empty tubing (Figure 2). Because this experiment was done in mid-late December, control IPIs were lower than in the previous work. Statistical analysis indicated significant main effects of time, treatment, and an interaction of the two. Two ewes had a complete inhibition during the posttreatment period; in the other three ewes, the hiatus in LH pulses was shorter, ranging from 84 to 108 minutes (Figure 2). Thus, the longest hiatus between pulses was significantly greater postimplantation (148 ± 27 min) than before (62.4 ± 7.0 min), whereas there was no significant differences in these variables with control treatments. Mean LH concentrations were significantly inhibited by SB222200 (Table 1), but LH pulse amplitude was not analyzed in this group because three of five ewes had no pulses during one time interval. There was no significant effect of control treatments on mean LH (Table 1) or LH pulse amplitude (Figure 2). Interestingly, in the two ewes with misplaced microimplants (one posterior and one dorsal), SB222200 appeared to increase episodic LH secretion (Supplemental Figure 2). These data were not statistically analyzed because of the low animal number.

Figure 2.

Panels on left depict LH pulse patterns in two ewes receiving empty (open bars) and SB222200-containing (shaded bars) microimplants into the ARC. Ewes were selected to depict shortest (left panels) and longest (right panels) interruption of LH pulses after antagonist treatment. Solid circles depict peaks of identified LH pulses. Bars on right present mean (± SEM) LH interpulse IPIs (left) and AMPLs (right) in response to control (top panel) and SB222200 (bottom panel). Open bars, Pretreatment values; shaded bars, values for 0–2 hours after microimplantation; black bars, values for 2–4 hours after microimplantation; striped bar, not analyzed due to low animal numbers. *, P < .05 vs pretreatment values

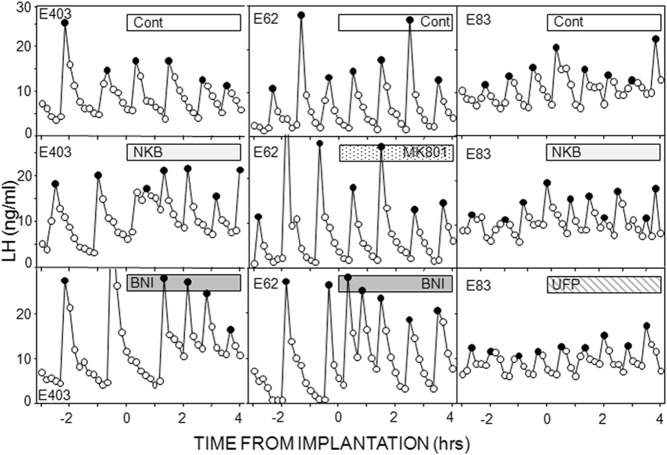

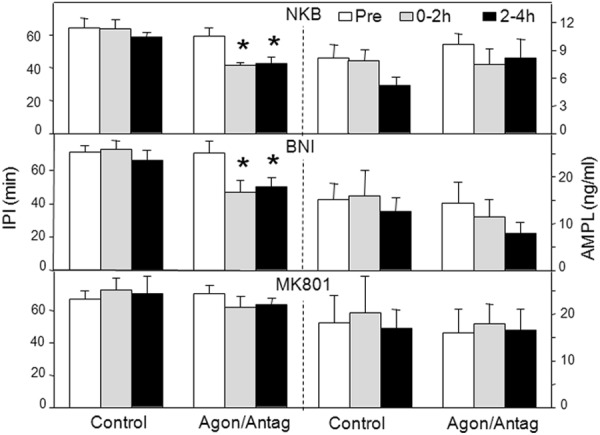

Effects of NKB and antagonists to the κ-opioid receptors and NMDA receptors

We next examined the effects of NKB and receptor antagonists for two other neurotransmitters in KNDy neurons. There was again no effect of empty microimplants on LH pulse frequency or amplitude (Figures 4 and 5). NKB-containing microimplants clearly decreased IPI in seven of nine ewes and produced a more modest decrease in the other two ewes. This decrease in IPI was sustained in most ewes, so IPI was significantly less during both treatment periods than before treatment (Figures 4 and 5). There was no effect of NKB on LH pulse amplitude (Figure 5) or mean LH concentrations (Table 1), and NKB had no effect in the ewes with missed microimplantation sites (data not shown).

Figure 4.

LH pulse patterns in one ewe from each replicate in experiment 5 with duration of treatment indicated by bars. In first replicate (left panels), ewes received empty (cont), NKB, and BNI-filled microimplants into the ARC. Treatments in second replicate (middle panels) were empty implants, an NMDA receptor antagonist (MK801), BNI, and acyline (pulse pattern shown in Figure 6). Ewes in the final replicate received control microimplants that were empty, or contained NKB, or the antagonist to the orphanin-FQ receptor (UFP-101). Solid circles depict peaks of identified LH pulses.

Figure 5.

LH pulse IPIs (left) and AMPLs (right) in response to NKB (top panel), and antagonists for the κ-opioid receptor (middle panel), the NKDA receptor (bottom panel). Bar codes are the same as in Figure 2. *, P < .05 vs pretreatment values.

We used BNI and MK-801 to test for the roles of dynorphin and glutamate, respectively, in the ARC. Because there was no previous work demonstrating the effectiveness of MK-801 in ewes, we first tested this antagonist in another area (the retrochiasmatic area of anestrous ewes) in which NMDA receptors have been implicated in inhibition of LH pulse frequency (47). Insertion of microimplants containing MK-801 into this area (n = 7) significantly increased LH pulse frequency (2.6 ± 0.6 pulses per 4 h) compared with controls (1.0 ± 0.3 pulses per 4 h). The effects of BNI were initially tested in the same six ewes that received NKB but successfully in only three ewes (two had incorrect placements and one animal that had received NKB had an obstructed guide tube). Therefore, we examined the effects of BNI, and MK-801, in an additional seven ewes, five of which had correct placements.

Administration of BNI markedly decreased IPI in the 2-hour postimplantation in six of seven ewes, and this decreased IPI was maintained during the last 2 hours in four of them so that IPI was significantly lower in both periods (Figures 4 and 5). There was no significantly effect of BNI on LH pulse amplitude (Figure 5) or mean LH concentrations (Table 1). MK-801 had no significant effect on IPI or LH pulse amplitude (Figure 5) or mean LH concentrations (Table 1). It should be noted that the increased LH pulse frequency in these ewes when treated with BNI serves as a useful positive control.

Possible effects of GnRH input to the ARC

Because GnRH-containing afferents onto KNDy neurons were evident, we examined the possible role of two constituents of these neurons, GnRH and orphanin-FQ, using antagonists to their receptors: acyline and UFP-101, respectively. Although acyline increased IPI in one ewe, neither antagonist had a statistically significant effect on LH pulse amplitude, IPI (Figure 6), or mean LH (Table 1) in these OVX ewes.

Figure 6.

Left, Top panels depict LH pulse patterns in one ewe receiving empty (open bar) and acyline-containing (shaded bar) microimplants into the ARC; note these data are from same ewe shown in Figure 4 (middle panel). Data in bottom panels are from one ewe given control (open bars) and an antagonist for the orphanin-FQ receptor (UFP-101); results from similar treatments in another ewe are illustrated in Figure 4, left panels. Right, Mean (± SEM) LH IPIs (left) and AMPLs (right) in response to control and antagonist treatments into the ARC; bar codes are the same as in Figure 2. There were no statistical differences with either treatment.

Discussion

These results provide evidence that kisspeptin and NKB act in the ARC to increase LH (and GnRH) pulse frequency, whereas dynorphin acts in this region to hold pulse frequency in check. In contrast, these data do not support an important role for glutamate, acting via NMDA receptors, or orphanin-FQ in the control of LH pulse frequency in OVX ewes. Similarly, GnRH does not appear to be important for control of episodic secretion, even though GnRH neurons send afferent projections to a subset of the KNDy cell population. The decrease in LH secretion seen after empty guide tubes were inserted into tissue but not when they extended just to the tip of the guide tubes (Figures 1–4), although unexpected, supports the hypothesis that this area plays an important role in driving episodic GnRH secretion.

The present study provides the first direct evidence in sheep that KNDy neurons receive monosynaptic input from GnRH neurons and is consistent with confocal analyses demonstrating GnRH-immunoreactive close contacts onto kisspeptin neurons in monkeys (48). Although the GnRH/synaptophysin-containing inputs were identified only at the light microscopic level, we have previously demonstrated that synaptophysin-positive close contacts seen with confocal analysis reliably indicate bona fide synapses when the same material is examined under the electron microscope (49). Because KNDy neurons also project to GnRH neurons in both the preoptic area and medial basal hypothalamus (50), this observation raises the possibility of reciprocal connections between these sets of neurons. However, it is not clear whether true reciprocal connections exist because only 45%-60% of GnRH neurons receive KNDy inputs, GnRH-containing contacts on KNDy neurons were seen in only 17% of cells, and the specific source of these GnRH inputs remains to be determined. The presence of GnRH contacts onto KNDy neurons is consistent with the hypothesis that GnRH plays a role in controlling the activity of these neurons and could provide a simple explanation for termination of each GnRH pulse. This hypothesis is supported by the report that the GnRH-receptor antagonist, Nal-Glu, stimulated GnRH pulse frequency in luteal phase ewes (38), but we observed no effect of acyline microimplants in the ARC on LH pulse frequency or amplitude. It thus seems unlikely that GnRH input to KNDy neurons plays an important role in episodic GnRH secretion, although we cannot rule out the possibility that an insufficient number of GnRH receptors were blocked with the microimplants of acyline. Nevertheless, this conclusion is consistent with other data in sheep (51) and the inability of either a GnRH receptor agonist or antagonist to alter bursts of MUA in OVX monkeys (52). In contrast, GnRH increased bursting of MUA in the rat (53) and stimulated the GnRH release from the murine GT1–7 cells (3).

Because acyline was ineffective, we also tested whether another product of ovine GnRH neurons, orphanin-FQ, is important for episodic LH secretion. Orphanin-FQ is found in all GnRH neurons and exogenous orphanin-FQ inhibits LH pulse frequency in OVX ewes (40). Because microimplants of UFP-101 into the ARC had no effect on episodic LH secretion, we conclude that orphanin-FQ released from these inputs is probably not important for steroid-independent control of GnRH pulses. This conclusion is consistent with the recent observation that icv administration of this antagonist increased episodic LH secretion only in the presence of progesterone (54). Although the failures of acyline and UFP-101 to affect LH secretion do not rule out roles for other components of GnRH neurons in control of GnRH pulses, they raise the possibility that the GnRH input to KNDy neurons plays another role. One possibility is that this input may be important for modifying KNDy cell function during the preovulatory GnRH surge because MUA activity decreases, or is completely eliminated, during the LH surge in monkeys (55), goats (56), and rats (57).

Although these results do not support a role for inhibitory GnRH neural input, they are consistent with the hypothesis that dynorphin release inhibits KNDy cell activity to terminate each pulse because BNI microimplants consistently increased LH pulse frequency. These data confirm and extend previous data demonstrating that icv administration of BNI accelerates bursts of MUA in OVX goats (9). In contrast, BNI had no effect on LH pulse frequency in OVX rats when given icv (58) or into the ARC (59), so there may be significant species differences for the role of dynorphin in pulse generation. In this regard, recent evidence supports a role for dynorphin in estrogen-negative feedback in rats (58), but endogenous opioid peptides do not appear to be involved in this action in ewes (34). In contrast, there is strong evidence that dynorphin participates in progesterone-negative feedback in both pregnant rats (60) and luteal-phase ewes (8). Thus, it appears that dynorphin inhibits episodic LH secretion in rats, goats, and sheep, but this inhibitory activity is evident only in OVX animals in the latter two species.

Of the three possible stimulatory transmitters in KNDy neurons, the data reported here support a role for NKB and kisspeptin, but not glutamate, in maintaining episodic GnRH secretion. The lack of effect of the NMDA receptor antagonist is somewhat surprising because KNDy neurons receive significant glutamatergic input (61). Furthermore, NMDA stimulates bursting activity of KNDy neurons in slice preparations (62) and induces pulsatile LH secretion in sheep (63) and other species (64) including primates (65). However, the lack of effect of MK-801 is consistent with an earlier report that icv administration of a different NMDA receptor antagonist had no effect on LH pulse patterns in OVX lambs (66). Perhaps glutamate acts via both NMDA and 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazol propionic acid receptors to stimulate KNDy neurons so that the blockade of both receptor types is needed to produce an effect.

The local effects of NKB in the ARC to stimulate LH pulse frequency seen here confirm and extend previous data demonstrating that icv administration of NKB accelerates MUA bursts in OVX goats (9). Interestingly, in that study NKB inhibited LH concentrations; because that effect was not observed in this work, one can infer that NKB acts in the ARC to stimulate MUA and LH pulse frequency but produces inhibitory effects on LH secretion elsewhere in the ovine hypothalamus. We also did not see the typical inverse relationship between pulse frequency and amplitude, probably because of the short duration of the treatment. These results are consistent with accumulating data from a number of species, including sheep, that the stimulatory effects of NK3R agonists are mediated by kisspeptin release from KNDy neurons (28–33). It should be noted, however, that senktide inhibited episodic LH secretion and bursts of MUA in OVX rats (67); interestingly, this action of senktide appears to be mediated by dynorphin (59). Although there are thus considerable data on the actions of exogenous NK3R agonists, this is the first report that an NK3R antagonist (SB222200) disrupts episodic LH secretion in OVX animals. In contrast, in OVX rats, SB222200 (59) and another specific NK3R antagonist (32) had no effect on episodic LH secretion. Thus, as was the case with dynorphin, there appear to be species differences in the role of endogenous NKB, but the opposite effects of NKB and the NK3R antagonist in this study provides strong support for the proposed role of NKB in initiating each GnRH pulse in sheep. The infertility (20) and suppression of episodic LH secretion (68) seen in humans with inactivating mutations of NKB signaling are also consistent with this postulated role for NKB.

The ability of microimplants of a Kiss1r antagonist to inhibit LH pulses and for microinjections of this antagonist to slow pulse frequency suggests that endogenous kisspeptin may act in the ARC to stimulate LH pulse frequency in OVX ewes. This is somewhat surprising because exogenous kisspeptin did not alter the frequency of MUA in OVX goats (25) and rats (69), but our data are consistent with the effects of intra-ARC injections of a similar Kiss1r antagonist (peptide 234) in OVX rats (70). It should be noted that both studies of MUA used iv injection of kisspeptin-10 so this peptide may not have reached the ARC at effective concentrations. One possible explanation for the effects of the antagonist is that it diffused to the median eminence to block kisspeptin effects on GnRH terminals (71), but this is unlikely because it produced only a 40% increment in IPI in our study and no effects on LH pulse amplitude of intra-ARC administration were observed when this antagonist was given into the ARC of sheep or rats (70). Although endogenous kisspeptin appears to act within the ARC to stimulate GnRH/LH pulse frequency, the specific neurons affected remain to be determined. There is evidence for Kiss1r mRNA in the ARC of several species, including sheep and rats (72), but the only cellular analysis has been done in sheep, in which Kiss1r mRNA was found only in cells that did not express Kiss1 mRNA (71).

In conclusion, the results indicate that input from GnRH neurons to the ARC is likely not important to the control of GnRH pulse frequency, but endogenous kisspeptin may act in this area to stimulate GnRH pulse frequency. The data also provide strong support for the hypotheses that NKB acts in the ARC to initiate each GnRH pulse, whereas the inhibitory actions of dynorphin are important for pulse termination in ewes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Heather Bungard, Jennifer Lydon, and Cheri Felix (West Virginia University Food Animal Research Facility) and Dr Margaret Minch for the care of the animals and Paul Harton for his technical assistance in sectioning tissue. We also thank Dr Al Parlow and the National Hormone and Peptide Program for reagents used to measure LH and the Contraception and Reproductive Health Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for acyline.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HD039916 and RO1-HD017864.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AMPL

- LH pulse amplitude

- ARC

- arcuate nucleus

- BNI

- nor-binaltorphimine

- icv

- intracerebroventricular

- IPI

- interpulse interval

- KNDy

- kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin

- MUA

- multiunit electrical activity

- NKB

- neurokinin B

- NMDA

- N-methyl-D-aspartate

- OVX

- ovariectomized.

References

- 1. Karsch FJ. Central actions of ovarian steroids in the feedback regulation of pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone. Annu Rev Physiol. 1987;49:365–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belchetz PE, Plant TM, Nakai Y, Keogh EJ, Knobil E. Hypophysial responses to continuous and intermittent delivery of hypopthalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Science. 1978;202:631–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krsmanovic LZ, Stojilkovic SS, Mertz LM, Tomic M, Catt KJ. Expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors and autocrine regulation of neuropeptide release in immortalized hypothalamic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3908–3912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moenter SM, DeFazio AR, Pitts GR, Nunemaker CS. Mechanisms underlying episodic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:79–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Terasawa E. Cellular mechanism of pulsatile LHRH release. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998;112:283–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, et al. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1614–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10972–10976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL. Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3479–3489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wakabayashi Y, Nakada T, Murata K, et al. Neurokinin B and dynorphin A in kisspeptin neurons of the arcuate nucleus participate in generation of periodic oscillation of neural activity driving pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the goat. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3124–3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Chavkin C, Okamura H, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by kisspeptin/dynorphin/neurokinin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11859–11866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rance NE, Krajewski SJ, Smith MA, Cholanian M, Dacks PA. Neurokinin B and the hypothalamic regulation of reproduction. Brain Res. 2010;1364:116–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goodman RL, Lehman MN, Smith JT, et al. Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the ewe express both dynorphin A and neurokinin B. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5752–5760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burke MC, Letts PA, Krajewski SJ, Rance NE. Coexpression of dynorphin and neurokinin B immunoreactivity in the rat hypothalamus: morphologic evidence of interrelated function within the arcuate nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:712–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. True C, Kirigiti M, Ciofi P, Grove KL, Smith MS. Characterisation of arcuate nucleus kisspeptin/neurokinin B neuronal projections and regulation during lactation in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:52–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rance NE. Menopause and the human hypothalamus: evidence for the role of kisspeptin/neurokinin B neurons in the regulation of estrogen negative feedback. Peptides. 2009;30:111–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hrabovszky E, Sipos MT, Molnar CS, et al. Low degree of overlap between kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin immunoreactivities in the infundibular nucleus of young male human subjects challenges the KNDy neuron concept. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4978–4989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cravo RM, Margatho LO, Osborne-Lawrence S, et al. Characterization of Kiss1 neurons using transgenic mouse models. Neuroscience. 2011;173:37–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merkley CM, Coolen LM, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Colocalization of glutamate within kisspeptin cells and their projections onto GnRH neurons in the ewe. Paper presented at: 7th International Congress of Neuroendocrinology; July 2010; Rouen, France (Abstract P2–10) [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kallo I, Vida B, Deli L, et al. Co-localisation of kisspeptin with galanin or neurokinin B in afferents to mouse GnRH neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24:464–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet. 2009;41:354–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foradori CD, Amstalden M, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Colocalisation of dynorphin a and neurokinin B immunoreactivity in the arcuate nucleus and median eminence of the sheep. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:534–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krajewski SJ, Burke MC, Anderson MJ, McMullen NT, Rance NE. Forebrain projections of arcuate neurokinin B neurons demonstrated by anterograde tract-tracing and monosodium glutamate lesions in the rat. Neuroscience. 2010;166:680–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wakabayashi Y, Yamamura T, Sakamoto K, Mori Y, Okamura H. Electrophysiological and morphological evidence for synchronized GnRH pulse generator activity among kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin A (KNDy) neurons in goats. J Reprod Dev. 2013;59:40–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amstalden M, Coolen LM, Hemmerle AM, et al. Neurokinin 3 receptor immunoreactivity in the septal region, preoptic area and hypothalamus of the female sheep: colocalisation in neurokinin B cells of the arcuate nucleus but not in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ohkura S, Takase K, Matsuyama S, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone pulse generator activity in the hypothalamus of the goat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:813–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Kisspeptin neurons from mice to men: similarities and differences. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5015–5018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roseweir AK, Kauffman AS, Smith JT, Guerriero KA, et al. Discovery of potent kisspeptin antagonists delineate physiological mechanisms of gonadotropin regulation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3920–3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Navarro VM, Castellano JM, McConkey SM, et al. Interactions between kisspeptin and neurokinin B in the control of GnRH secretion in the female rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E202–E210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Wu M, et al. Regulation of NKB pathways and their roles in the control of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4265–4275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ramaswamy S, Seminara SB, Plant TM. Evidence from the agonadal juvenile male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) for the view that the action of neurokinin B to trigger gonadotropin-releasing hormone release is upstream from the kisspeptin receptor. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94:237–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garcia-Galiano D, van Ingen Schenau D, Leon S, Krajnc-Franken MA, et al. Kisspeptin signaling is indispensable for neurokinin B, but not glutamate, stimulation of gonadotropin secretion in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:316–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noritake K, Matsuoka T, Ohsawa T, et al. Involvement of neurokinin receptors in the control of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in rats. J Reprod Dev. 2011;57:409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grachev P, Li XF, Lin YS, et al. GPR54-dependent stimulation of luteinizing hormone secretion by neurokinin B in prepubertal rats. PloS One. 2012;7:e44344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goodman RL, Parfitt DB, Evans NP, Dahl GE, Karsch FJ. Endogenous opioid peptides control the amplitude and shape of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses in the ewe. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2412–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodman RL, Holaskova I, Nestor CC, et al. Evidence that the arcuate nucleus is an important site of progesterone negative feedback in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3451–3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Billings HJ, Connors JM, Altman SN, et al. Neurokinin B acts via the neurokinin-3 receptor in the retrochiasmatic area to stimulate luteinizing hormone secretion in sheep. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3836–3846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goodman RL, Maltby MJ, Millar RP, et al. Evidence that dopamine acts via kisspeptin to hold GnRH pulse frequency in check in anestrous ewes. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5918–5927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Padmanabhan V, Evans NP, Dahl GE, McFadden KL, Mauger DT, Karsch FJ. Evidence for short or ultrashort loop negative feedback of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62:248–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Herbison AE, Hubbard JI, Sirett NE. LH-RH in picomole concentrations evokes excitation and inhibition of rat arcuate neurones in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1984;46:311–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foradori CD, Amstalden M, Coolen LM, et al. Orphanin FQ: evidence for a role in the control of the reproductive neuroendocrine system. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4993–5001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Anderson GM, Connors JM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Goodman RL. Oestradiol microimplants in the ventromedial preoptic area inhibit secretion of luteinizing hormone via dopamine neurones in anoestrous ewes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:1051–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Skinner DC, Harris TG, Evans NP. Duration and amplitude of the luteal phase progesterone increment times the estradiol-induced luteinizing hormone surge in ewes. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1135–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goodman RL, Bittman EL, Foster DL, Karsch FJ. Alterations in the control of luteinizing hormone pulse frequency underlie the seasonal variation in estradiol negative feedback in the ewe. Biol Reprod. 1982;27:580–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith JT, Coolen LM, Kriegsfeld LJ, et al. Variation in kisspeptin and RFamide-related peptide (RFRP) expression and terminal connections to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the brain: a novel medium for seasonal breeding in the sheep. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5770–5782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goodman RL, Karsch FJ. Pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone: differential suppression by ovarian steroids. Endocrinology. 1980;107:1286–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Anderson GM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Billings HJ, Connors JM, Goodman RL. Evidence that thyroid hormones act in the ventromedial preoptic area and the premammillary region of the brain to allow the termination of the breeding season in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2892–2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Singh SR, Hileman SM, Connors JM, et al. Estradiol negative feedback regulation by glutamatergic afferents to A15 dopaminergic neurons: variation with season. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4663–4671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ramaswamy S, Guerriero KA, Gibbs RB, Plant TM. Structural interactions between kisspeptin and GnRH neurons in the mediobasal hypothalamus of the male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) as revealed by double immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4387–4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Adams VL, Goodman RL, Salm AK, Coolen LM, Karsch FJ, Lehman MN. Morphological plasticity in the neural circuitry responsible for seasonal breeding in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4843–4851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Merkley CM, Coolen LM, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Direct projections of arcuate KNDy (kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin) neurons to GnRH neruons in the sheep. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; November 2011; Washington, DC (Abstract 712.705) [Google Scholar]

- 51. Caraty A, Locatelli A, Delaleu B, Spitz IM, Schatz B, Bouchard P. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and GnRH antagonists do not alter endogenous GnRH secretion in short-term castrated rams. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2523–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ordog T, Chen MD, Nishihara M, Connaughton MA, Goldsmith JR, Knobil E. On the role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in the operation of the GnRH pulse generator in the rhesus monkey. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hiruma H, Kimura F. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone is a putative factor that causes LHRH neurons to fire synchronously in ovariectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61:509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nestor CC, Cheng G, Nesselrod GL, et al. Evidence that orphanin FQ mediates progesterone negative feedback in the ewe. Endocrinology. [Published online August 8, 2013] doi:10.1210/en.2013-1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. O'Byrne KT, Thalabard JC, Grosser PM, et al. Radiotelemetric monitoring of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator activity throughout the menstrual cycle of the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1991;129:1207–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tanaka T, Mori Y, Hoshino K. Hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator activity during the estradiol-induced LH surge in ovariectomized goats. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;56:641–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nishihara M, Sano A, Kimura F. Cessation of the electrical activity of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator during the steroid-induced surge of luteinizing hormone in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;59:513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mostari MP, Ieda N, Deura C, et al. Dynorphin-κ opioid receptor signaling partly mediates estrogen negative feedback effect on LH pulses in female rats. J Reprod Dev. 2013;59(3):266–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grachev P, Li XF, Kinsey-Jones JS, et al. Suppression of the GnRH pulse generator by neurokinin B involves a κ-opioid receptor-dependent mechanism. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4894–4904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gallo RV. κ-Opioid receptor involvement in the regulation of pulsatile luteinizing hormone release during early pregnancy in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 1990;2:685–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Merkley CM, Coolen LM, Padmanabhan V, Jackson LM, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Evidence for transcriptional activation of arcuate kisspeptin neurons, and glutamatergic input to kisspeptin during the preovulatory GnRH surge of the sheep. Presented at: 91st Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society; June 2009; Washington, DC (Abstract P3–220) [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gottsch ML, Popa SM, Lawhorn JK, et al. Molecular properties of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4298–4309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Estienne MJ, Schillo KK, Hileman SM, Green MA, Hayes SH. Effect of N-methyl-d,l-aspartate on luteinizing hormone secretion in ovariectomized ewes in the absence and presence of estradiol. Biol Reprod. 1990;42:126–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brann DW, Mahesh VB. Excitatory amino acids: evidence for a role in the control of reproduction and anterior pituitary hormone secretion. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:678–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gay VL, Plant TM. N-methyl-D,L-aspartate elicits hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone release in prepubertal male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Endocrinology. 1987;120:2289–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hileman SM, Schillo KK, Estienne MJ. Effects of intracerebroventricular administration of D,L-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, on luteininizing hormone release in ovariectomized lambs. Biol Reprod. 1992;47:1168–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kinsey-Jones JS, Grachev P, Li XF, et al. The inhibitory effects of neurokinin B on GnRH pulse generator frequency in the female rat. Endocrinology. 2012;153:307–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Young J, George JT, Tello JA, et al. Kisspeptin restores pulsatile LH secretion in patients with neurokinin B signaling deficiencies: physiological, pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;97:193–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kinsey-Jones JS, Li XF, Luckman SM, O'Byrne KT. Effects of kisspeptin-10 on the electrophysiological manifestation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator activity in the female rat. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1004–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li XF, Kinsey-Jones JS, Cheng Y, et al. Kisspeptin signalling in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus regulates GnRH pulse generator frequency in the rat. PloS One. 2009;4:e8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Smith JT, Li Q, Yap KS, et al. Kisspeptin is essential for the full preovulatory LH surge and stimulates GnRH release from the isolated ovine median eminence. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1001–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lehman MN, Hileman SM, Goodman RL. Neuroanatomy of the kisspeptin signaling system in mammals: comparative and developmental aspects. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;784:27–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.