Abstract

Political violence is implicated in a range of mental health outcomes, including PTSD, depression, and anxiety. The social and political contexts of people’s lives, however, offer considerable protection from the mental health effects of political violence. In spite of the importance of people’s social and political environments for health, there is limited scholarship on how political violence compromises necessary social and political systems and inhibits individuals from participating in social and political life. Drawing on literature from multiple disciplines, including public health, anthropology, and psychology, this narrative review uses a multi-level, social ecological framework to enhance current knowledge about the ways that political violence affects health. Findings from over 50 studies were analyzed and used to build a conceptual model demonstrating how political violence threatens three inter-related domains of functioning: individual functioning in relationship to their environment; community functioning and social fabric; and governmental functioning and delivery of services to populations. Results illustrate the need for multilevel frameworks that move beyond individual pathology towards more nuanced conceptualizations about how political violence affects health; findings contribute to the development of prevention programs addressing political violence.

Introduction

Political violence is the deliberate use of power and force to achieve political goals (World Health Organization (WHO), 2002). As outlined by the World Health Organization (2002), political violence is characterized by both physical and psychological acts aimed at injuring or intimidating populations. Examples include shootings or aerial bombardments; detentions; arrests and torture; and home demolitions (Basoglu, Livanou, & Crnobaric, 2005; Clark et al., 2010; K. de Jong et al., 2002; E. F. Dubow et al., 2010; Farwell, 2004; Giacaman, Shannon, Saab, Arya, & Boyce, 2007; Hobfoll, Hall, & Canetti, 2012). The WHO definition of political violence also includes deprivation, the deliberate denial of basic needs and human rights. Examples include obstruction related to freedom of speech (e.g. activists who speak out against a regime being subject to torture (see, for instance, Robben, 2005)), and denial of access to food, education, sanitation, and healthcare (for instance, see International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), 1949; UNESCO, 2006; UNESCO: International Program for the Development of Communication (IPDC), 2012; United Nations Population Fund, 2007).

Particularly when we look at dimensions of deprivation within political violence, it is clear that political violence is intimately related to structural violence: the ways that structures of society (e.g. educational, legal, cultural, healthcare) insidiously act as “social machinery of oppression” (Farmer, 2006: 307) to regularly, systematically, and intentionally prohibit the realization of full human potential through unequal arrangements of social, economic, and political power (Farmer, et al., 2004, 2006; Galtung, 1969). Indeed, it is overwhelmingly clear that structural violence often precipitates, coexists with, and is deployed as a regular tool within political violence. Structural inequalities based, for instance, on class, nationalities, or ethnic groups often lead to political uprisings and rebellions and then to the yielding of power through violent repressions that characterize political violence (Cairns, et al., 1998; de Jong, 2010). In addition, it is usually the poorest and most disenfranchised that suffer the most within wars and conflicts as they are particularly targeted and/or face oppression and violence within a multitude of overlapping experiences (see, for instance: Al Gasseer, 2004; Berg, 2009; Lykes, et al., 2007; UNRISD (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development), 2005). Furthermore, political violence in the forms of repression, torture, and forced exile is often leveled specifically towards those who pose the most threat to the prevailing and oppressive social order (see, for instance: Blum, 2005; Esparza, 2005; Robben, 2005). Despite their mutual influence, authors, including Galtung (1969), who is widely credited with developing the initial framework for structural violence (Farmer, 2004), have proposed a few key points of differentiation between structural and political violence: whereas structural, “indirect” violence is covert, static, and lacks a clear aggressor, “direct” violence (what Galtung terms “personal violence”, but would also include political violence) is overt, dynamic, and connects a discernable aggressor with the victim (Galtung, 1969; Vorobej, 2008; Winter and Leighton, 2001). Although its relationship to structural violence will be clear as findings are presented below (and, in fact, the uncovering of this dynamic is one of the contributions of this overview), the research presented here centers on political violence, as defined above.

A considerable amount of research has examined how political violence is implicated in a variety of poor outcomes related to mental health, including PTSD, depression, and anxiety (Punamaki, 1990, Summerfield, 2000, de Jong et al, 2003, Barber, 2008, de Jong et al., 2008, Haj-Yahia, 2008). The WHO, for example, estimates that between one-third to one-half of people exposed to political violence will endure some type of mental distress, including PTSD, depression or anxiety (World Health Organization (WHO), 2001). In spite of these risks, however, we know that individuals and communities regularly manage the traumas of political violence as they demonstrate considerable resilience (Summerfield, 1999). Resilience- the successful recovery from or adaptation to hardship (Agaibi, 2005; Masten, et al., 1990) – is not an anomaly, but rather, is a predictable reaction to stress for both individuals and collectives (Bonanno, 2004; Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, & Pfefferbaum, 2008). While some individual traits may build resilience in the face of political violence (for reviews of these, see Betancourt and Khan, 2008; Masten, et al., 2012; Sousa, et al., 2013), resilience ultimately depends on the relationship between people and their social and political environments (Masten, et al., 2008; Shinn and Toohey, 2003; Ungar, 2011b). Individuals’ involvement in collectives, cohesive community networks, and democratic, responsive governmental systems are each central to health and well-being (Garbarino, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2007; Katz, 2001; Nowell and Boyd, 2010; Pfeiffer et al., 2008; Ungar, 2011a; World Health Organization, 2008).

For populations affected by political violence, resources within the environment (e.g., schools, community institutions, opportunities for social and political engagement, responsive public systems, and governmental accountability for atrocities committed against civilian populations) appear to offer protection against the deleterious impacts of political violence on health (Berk, 1998, Farwell and Cole, 2001, Lykes et al., 2007, Betancourt et al., 2010, Melton and Sianko, 2010). In spite of what we know, however, about the potential for social and political contexts to build resilience, there is limited health scholarship on how political violence threatens the individual-environment relationship, which we know is core to well-being (Kemp et al., 1997; Melton and Sianko, 2010). While it is increasingly recognized that political violence is a collective experience (Martín-Baró et al., 1994, Summerfield, 2000, Nelson, 2003, Robben, 2005, Giacaman et al., 2007c), we know more about its influence on individuals than we do about the ways it affects the larger groups, organizations, and government structures that underpin health and well-being.

However, particularly when we look across disciplines, there does exist some evidence about how political violence affects the dynamic relationships between individuals and the collective. This scholarship coincides with an increased attention to multilevel perspectives that transcend individual pathology through emphasizing social and political determinants of health (Krieger, 2001, 2008; Williams, 2002). Social ecological frameworks are particularly important for examinations of political violence because the violence simultaneously affects multiple domains related to individual and collective well-being (Hoffman & Kruczek, 2011; Martinez & Eiroa-Orosa, 2010), as it causes what Edelman, et al. (2003) refer to as the sociopolitical effects of political violence. Due to their comprehensive scope, multi-level frameworks enrich both scholarship on and intervention planning for political violence (Dubow et al., 2009; Tol, 2010). Accordingly, this review aims to enhance the literature on political violence by examining and synthesizing literature from across multiple disciplines to improve our understandings about the implications of political violence for collective well-being.

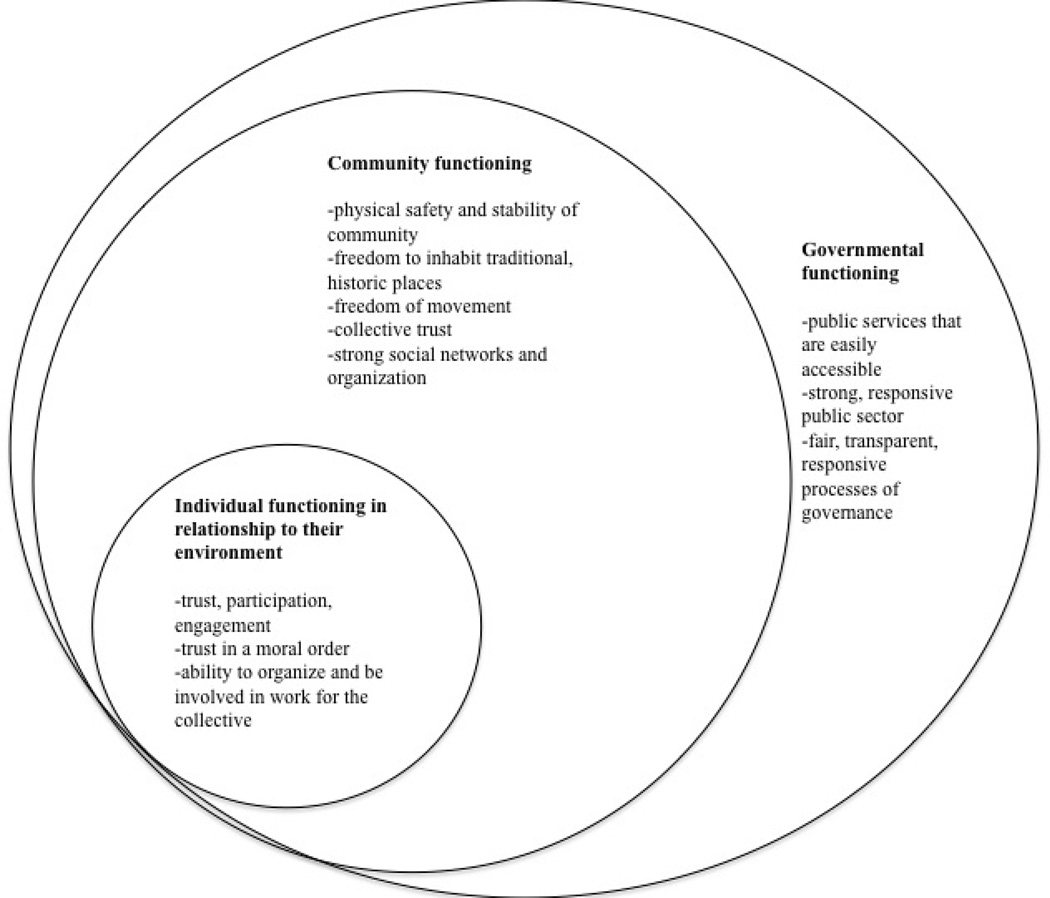

The term collective in this review refers to three inter-related domains of functioning: individuals’ ability to participate in social and political life; community functioning and social fabric; and governmental functioning and delivery of services to populations (see Figure 1). These three domains, which were built and clarified through the process of synthesizing the literature for the review, represent the central organizing framework for this paper. In line with Brofenbrenner’s theories (1986), which referred to bidirectional relationships between domains of functioning as mesosystems, this review also considers how political violence harms the relationship between areas of collective functioning. For instance, it considers how political violence might affect governmental functioning, which then weakens individuals’ willingness to engage in political life.

Figure 1.

Domains of collective functioning

Methods

For both local and outside researchers alike, within political violence there is little assurance for the safety or the stability and infrastructure needed for extended fieldwork, or for in-depth, large-scale, and/or longitudinal studies. Furthermore, as Krieger (2008) asserts, as a whole, social ecological examinations of health are still new, and accordingly, there are still ongoing deliberations regarding some of the core constructs like proximal, distal, and level. Although political violence, with its multi-level repercussions, demonstrates the need for social ecological perspectives, its complex nature, variations in its expression across locations and time points, and the range of evidence required for sound evaluation of its effects across levels (particularly at the collective level) all present special challenges for research. With these issues in mind, this review deliberately utilizes an integrated design to draw on findings from across disciplines (including public health, anthropology, geography, sociology, and psychology) and methodologies (for more on the advantages and disadvantags of integrated review studies, see Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., & Barroso, J., 2006; Voils, Sandelowski, Barroso, & Hasselblad, 2008). The variety of disciplines and methods represented in this review illustrate the importance of scholarship that is qualitative in nature, that is the product of reflections from professionals with extended time in the field, and/or that are overviews resulting from authors’ analyses of official reports or statistics, architecture, policies or programs, or historical events. Although aspects of systemic review processes were employed (evident in the explanation of the search strategy described below), this is a narrative review. A narrative format was chosen due the advantages it offers in terms of drawing on a wide array of disciplines and methods of inquiry, and its consequent fit with integrated approaches to reviews of literature (for more on the importance of narrative reviews, see for instance, Murphy, 2012).

To meet inclusion criteria, articles must be peer reviewed, published in English, and address the research question of how political violence directly affects individuals’ abilities to interact with collective structures or the collective structures themselves (e.g. community and governmental functioning). Psychinfo and PubMed databases were searched in 2011 using the key term “political violence”, resulting in 323 and 617 articles, respectively. Pubmed was searched using “war + infrastructure”, resulting in 309 articles (political violence + infrastructure only resulted in 17 articles so the search was done with the key term war instead of political violence). To further ensure representation of social science disciplines (and to provide a more updated search timeframe), an additional search was done in ProQuest in 2013 (limited to peer-reviewed sources), using the key words “political violence;” this resulted in 739 papers (many of which were duplicates on the original searches) that were searched, again first at the level of the title and the brief view of the abstract (where the search terms are highlighted in their context) and then at the level of the abstract. Excluding repeated articles, more than 1200 titles were initially reviewed, first based on their titles and then their abstracts.

Specific searches were also done within journals closely related to political violence (e.g. Conflict and Health, Disasters) or those with special issues or considerable space dedicated to political violence (e.g. Social Science and Medicine, Qualitative Sociology, Human Geography). Grey literature, author’s databases, and reference lists of published literature on related topics were also used; in this way, literature from relevant books were included and the search reached more deeply into the fields of geography and anthropology. Literature was not selected if it did not either address how political violence affects individuals’ involvement in the collective or reflect findings about how political violence affects collective structures (e.g., schools, healthcare, government systems, community well-being); for example, literature was rejected if it focused on the causes, rather than effects, of political violence; on the individual mental health implications of political violence; or solely on interventions related to political violence. In the end, fifty-three articles and 9 books or book sections were retained for review and analysis.

Results

Investigation and synthesis of the literature resulted in the establishment of three broad categories of collective functioning (each containing several sub-themes): (1) individuals’ ability to participate in social and political life; (2) community functioning and social fabric; and (3) governmental functioning. The review is organized according to these three domains. The discussion provides an analysis of the effects of political violence across these three domains. Table 1 illustrates the central organizing framework for the findings, and shows the number, methods, and locations of studies with respect to the three domains of collective functioning investigated. Table 2 provides the locations and descriptions of political violence provided by authors included in this review.

Table 1.

Phenomena, Methodology, Number*, and Locations of Studies

| Phenomenon | Survey research | Narrative research (e.g., interviews, focus groups) |

Ethnography, prolonged fieldwork, participant observation |

Overview based on analysis of existing evidence** |

total # of studies (# empirical, #overview)* |

Locations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influence on individuals’ ability to participate in social and political life | Isolation, mistrust, suspicion, withdrawal | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 10 (9 ,1) | Argentina, El Salvador, Northern Ireland, Peru, Guatemala, Burma, Kosovo, Indian Kashmir Valley |

| Deterioration of trust in moral order, justice, government entities, democracy | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 (5, 2) | Guatemala, Nicaragua, Former Yugoslavia, Northern Ireland | |

| Weakened ability of individuals to organize and work collectively | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 (7, 1) | Argentina, Guatemala, Bosnia, Burma | |

| Influence on community functioning/social fabric | Mass killings or disappearances | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 9 (7, 2) | Peru, Guatemala, Croatia, Colombia, El Salvador, Argentina, Nicaragua |

| Displacement and migration | 4 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 12 (7, 5) | Northern Ireland, Zimbabwe, Peru, Sri Lanka, Bosnia, El Salvador, North America | |

| Wide-scale physical destruction of places, including those of special meaning | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 (2, 4) | Croatia, Guatemala, Palestine, Iraq, Bosnia | ||

| Control of space and movement | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 13 (7, 6) | Iraq, Argentina, Northern Ireland, Palestine, Burma, South Africa, North America, Peru, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nepal | |

| Instillation of collective fear & terror | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 (5, 3) | Nicaragua, Colombia, Guatemala, Burma, El Salvador, Israel | ||

| Destruction of social networks | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 (8, 1) | Burma, Guatemala, Peru | |

| Diminishment of the number and strength of community organizing activities | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 9 (7, 2) | Guatemala, Burma, Zimbabwe, Peru, El Salvador | |

| Influence on governmental functioning and delivery of services to populations | Deterioration of public utilities | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 (3, 5) | Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Gaza, West Bank | |

| Deterioration of medical systems | 2 | 12 | 14 (2, 12) | Throughout Africa, Haiti, Pakistan, Iraq, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, Afghanistan, Guatemala, Zimbabwe, the Philippines, El Salvador, Croatia, Bosnia, Palestine, Kashmir | |||

| Deterioration of school systems | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 (2, 1) | Mozambique, Palestine, Burma | |

| Deterioration of public sector and governments’ ability to provide for its citizenry | 10 | 10 (10) | Throughout Africa, El Salvador, Haiti, Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Somalia | ||||

| Destruction of governance processes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 (3, 4) | Guatemala, El Salvador, Somali, global evaluations, Nicaragua |

NOTE: Categories are not mutually exclusive; studies often had multiple phenomenon, method, and location, and they are counted in each of these that they report.

Overviews included historical, policy, or program analyses using official government reports, news reports, or budgets; spatial data (e.g., maps, architecture); and existing literature

Table 2.

List of locations & short explanation of political violence, as reported by study authors*

| Location | Authors | Timeline, if given, & characterization of political violence by authors |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | (Ityavyar and Ogba, 1989) | 1960–1987: violence and political conflicts |

| Afghanistan | (Salvage, 2007, Acerra et al., 2009) | 1979–1989: invasion and war with Soviet Union; internal factional fighting, 2001: US invasion |

| Argentina | (Robben, 2005) | 1955–1979: armed violence, 1976: start of state terror and "dirty war" against citizens |

| Bosnia | (Jones, 2002, Carballo et al., 2004, Coward 2004, Jones and Kafetsios, 2005, Simunovic, 2007) | 1992–1995; war |

| Burma | (Skidmore, 2003) | beginning 1998; totalitarian state control |

| Colombia | (Oslender, 2007) | beginning 1980s: internal crises, armed struggles for power |

| Croatia | (Dulic, 2006) | 1941–1945; war |

| (Violich, 1998) | 1991–5: war | |

| El Salvador | (Jenkins, 1991, Martín-Baró et al., 1994, Ugalde et al., 2000) | 1979–92 civil war, culmination of militarisation and political repression |

| Guatemala | (Lykes, 1997, Preti, 2002, Esparza, 2005, Lykes et al., 2007, Flores et al., 2009, Pedersen et al., 2010) | long history of conflict and violence, dating back to BC; written records of violence, torture, massacres from invasion of conquistadores in 1533 and throughout colonization from 16th-19th century; 1960–1996; civil war between army and left-wing guerillas, amidst non-violent leftist organizing for land reform, civil rights, democracy |

| Haiti | (Farmer, 2004) | 1991: violent coup |

| Iraq | (Basu, 2004, Graham, 2004, Hamid and Everett, 2007, Salvage, 2007, Gregory, 2008) | beginning 2003: invasion and war |

| Ireland | (Feldman, 2003, Dillenburger et al., 2008) | beginning 1969: sectarian violence and political conflict |

| Israel | Bar-Tal, et al., 2001 | protracted conflict |

| Kashmir Valley | (de Jong et al., 2008) | beginning 1947: disputed ownership of region, liberation struggle between India and Kashmiri militants |

| Kosovo | (Jones et al., 2003, Morina and Ford, 2008, Wang et al., 2010) | 1998–99: war and inter-ethnic violence |

| Lebanon | (Graham, 2004, Hamieh and Ginty, 2010) | 2006: war between Hezbollah and Israel in Lebanon |

| Mozambique | (Garbarino et al., 1992) | war |

| Nepal | (Tol et al., 2010) | beginning 1740: armed rebellions against autocratic rule, 1950: armed insurrection, 1971: uprising, 1996–2006: armed insurgency |

| Nicaragua | (Garfield et al., 1987, Tully, 1995) | 1936–1990: brutal dictatorship followed by US financed civil war |

| North America indigenous lands | (Evans-Campbell, 2008) | community massacres, genocidal policies |

| Pakistan | (Yusufzai, 2008) | 2005: US-led "war on terror" |

| Palestine | (Barghouthi and Giacaman, 1990, Giacaman et al., 2003, Segal et al., 2003, Giacaman et al., 2004, Graham, 2004, Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2006, Giacaman et al., 2007a, Weizman, 2007, Barber, 2008) | most of last century, continuing into 21st century; ongoing political conflict combined with invasion in 2002 |

| Peru | (Snider et al., 2004, Pedersen et al., 2008) | 1980s, early 1990s; civil war; aggression by both radical Maoist group and Peruvian military, including torture, murder and forced displacement |

| Somalia | (Menkhaus, 2010) | 1991–92: state collapse, civil war; 1993–95: armed conflict, 2007–08: external intervention, |

| South Africa | (Turshen, 1986, Yach, 1988) | 1960–1984: apartheid policies, stripping of citizenship, 1985–86: outbreak of violence related to apartheid policies |

| Sri Lanka | (de Jong et al., 2002, Reilley et al., 2002) | 1983–2002; civil war, armed ethnic conflict |

| Yugoslavia | (Basoglu et al., 2005b) | war |

| Zimbabwe | (Keller et al., 2008) | beginning 2007; state-sanctioned torture and political repression |

Note on locations reported on by multiple authors: If authors studied different time periods/conflicts in same place, separate lines are used. Otherwise, dates and characterization of conflicts use combined information

Influence of political violence on individual functioning in relationship to their envirornment

Participation in civil society and political processes is essential for the health and well-being of individuals (World Health Organization, 2008). It engenders a sense of responsibility for collective functioning, enhancing individual well-being (Nowell and Boyd, 2010). Political violence undermines individuals’ ability to engage with, and have confidence in, social and political life by: contributing to individuals’ isolation and withdrawal from society; deteriorating individuals’ trust in others, justice, and government entities and democracy itself; and lessening individuals’ abilities or willingness to engage in political activities.

Distrust, isolation, and withdrawal are consequences of political violence. Robben (2005) reported that political violence in Argentina inhibited individuals from interacting with others for collective purposes. Withdrawal, suspicion, mistrust and isolation of members from larger community and social life due to political violence were reported by Esparza (2005), Lykes, et al. (2007) and Flores, et al. (2009), who each examined political violence in Guatemala. Withdrawal, distrust and isolation were also reported from an array of research locations, including Dillenburger, et al. in Ireland (2008), Snider in Peru (2004), Skidmore in Burma (2003), and Jenkins’ research among refugees from El Salvador (1991). Morina and Ford’s research in Kosovo found 34.3% of participants reported symptoms of damaged relationships, including distrust and withdrawal (2008). De Jong, et al.’s research in the Indian Kashmir Valley (2008) found isolation, aggressive behavior, and ceasing to speak to people were the most commonly reported mechanisms used by respondents to cope with political violence (64.1%, 46.1%, and 36.9%, respectively), far above seeking support from family (12.4%) or talking to others (22.9%). Findings of isolation, mistrust and withdrawal resulting from political violence is consistent with scholars’ conclusions that mental health problems resulting from political violence rupture people’s ability to access help from their social environments (de Zulueta, 2007).

Political violence diminishes individuals’ trust in the moral organization of society, government entities and processes of democracy. Lykes, et al.’s study in Guatemala found the complicity of people’s own governments in political violence decreased individuals’ trust towards community and organizational processes (2007). This was also found by Flores, et al. in Guatemala (2009) and Tully in Nicaragua (1995), who reported distrust in institutions and systems of justice arose from political violence. Basoglu, el al. (2005c) found the trauma of war in Former Yugoslavia was compounded by participants’ perceptions that those responsible were not brought to justice. This conviction was associated with a drop in survivors’ belief in the basic goodness of people and a just order. Dillenburger, et al.’s (2008) study of political violence in Ireland found lasting bitterness among people towards larger society fueled by violence and the perception that perpetrators were not held accountable. This diminished belief in goodness of people and a just order, in turn, reduced people’s belief in democracy.

Political violence lessens the willingness of individuals to engage in political activities, including community organizing. Lykes, et al. (2007) found Mayan peasants in Guatemala targeted with violence due to their political organizing reported a preoccupation with defeatist and negative thoughts about community organizing as a result of political violence. Robben (2005) found that in Argentina torture was used against individuals to deter them from political engagement. Individuals may curtail social action to try to protect themselves from political violence, as reported by Skidmore in Burma (2003) and Esparza in Guatemala (2005). And, this disengagement may indeed offer psychological protection against the traumas of political violence, as found in Jones, et al.’s (2002) examination of political violence and engagement in political processes in Bosnia Herzegovina.

Influence of political violence on community functioning

Community is usually defined as a network of connections, often centered in a physical location, that encompass shared beliefs, circumstances, concerns and relationships (Chaskin, 2001). Community strength and connectedness is essential for the health and well-being of individuals, particularly when they are exposed to massive human tragedies (Hobfoll et al., 2007, Ungar, 2011a). Scholars propose communities function well due to collective efficacy, a combination of social cohesion, and the ability of the collective to operate as a unit that can affect change for the common good (Sampson, 2003, 2006). Political violence not only lessens individuals’ abilities to act within their communities, it also undermines the social foundations of a society (Summerfield, 2000), rupturing social fabric (collective histories, identities and values (Pedersen, 2002)) and often engendering collective senses of fear (Bar-Tal, et al., 2007). Studies reveal political violence deteriorates community functioning and social fabric by: (1) damaging community as a shared physical location of people, culture and identity through mass killings and displacement, destruction of meaningful places, and control of space and movement and (2) changing the overall climate and functioning of communities through instillation of collective fear and terror, destruction of networks, and diminishment of community organizing activities.

Mass killings were reported by Oslender in Colombia (2007), Duliá in Croatia (2006), and Jenkins in El Salvador (1991). Lykes, et al. (2007) report that in Guatemala, more than half of those killed were murdered in "group massacres aimed at destroying the whole community." Pedersen, et al. (2008) and Snider (2004) each conclude that in Peru, mass graves serve as visual reminders the target was not an individual but masses of people. Disappearances were reported by Robben (2005), Tully (1995) and Jenkins (1991) in Argentina, Nicaragua, and El Salvador, respectively. Massive displacement and migration due to political violence diminishes local and national networks, with scholars estimating the majority of the world’s 12 million refugees and 22 to 25 million internally displaced persons are fleeing political violence (Pedersen, 2002, Sidel and Levy, 2008). Massive displacement, internal and outward migration were reported as consequences of political violence by Dillenburger, et al. (2008), Carballo, et al. (2004), de Jong, et al. (2002), Pedersen, et al. (2008), Ugalde, et al. (2000), and Jones, et al. (2005) in their studies in Ireland, Bosnia, Sri Lanka, Peru, El Salvador and Zimbabwe. Evans-Campbell, et al. (2008) concluded forced displacement of American Indian children into boarding schools, adoptions and foster care has lasting consequences for communities, including loss of language and traditional practices and potential future leaders, ultimately jeopardizing the ability of a community to envision or plan its collective future.

Physical environments nurture communities by facilitating and rooting relationships and fulfilling needs for safety, comfort, and collective identity, history, and pride (Low and Altman, 1992, Fullilove, 1996). These are central to the dynamic relationship between person and environment, “mutually constituting entities (Kemp, forthcoming).” Violich (1998) concluded physical destruction caused by political violence in Croatia diminished the sense of unity and collectivity. Coward, who examined the destruction of urban spaces (or urbicide) in Bosnia within political violence, concluded there is a "certain kinship" between urbicide and genocide; physical destruction is intimately related to cultural destruction of peoples (Coward 2004). Acts of political violence include the demolitions of homes and businesses and the destruction of entire villages. Giacaman, et al. (2004) reported 31% to 87% of homes or businesses within the five villages studied in Palestine were destroyed due to Israeli invasions. Lykes, et al., (2007) reported that in Guatemala, acts of political violence included destruction of more than 400 villages.

Destruction of meaningful places representing community, culture and religion is an assault against collective identity. Sacred sites include places of communal space or land with shared historical and religious meaning; closures, take-overs and bombings represent particular, deliberate wounds to the cultural and spiritual lives of the community, as Coward (2004), Gregory (2008) and Violich (1998) found in Bosnia, Iraq and Croatia. Trauma to sacred sites may include denigration of the land itself through dumping of hazardous materials, as noted by Evans-Campbell, et al.’s research with American Indian and Alaska Native populations (2008). Destruction of collective land may be particularly harmful for indigenous populations whose attachment to the land may represent particular sets of social relations, as Lykes (1997) found in Guatemala.

Control of physical space and the populations therein is a primary objective of political violence (Graham, 2004, Gregory, 2008). In Feldman’s (2003) study of urban geography in Ireland, findings showed one-way streets and cul-de-sacs, roads with no escape where fighting parties are easily trapped, are fundamental to the militarization of space. Segal, et al. (2003), Weizman (2007), Gregory (2008), Skidmore (2003) and Turshen (1986) found in Palestine, Iraq, Burma, and South Africa that military roads, checkpoints, barricades, and networks symbolize and actualize control over territories where populations were previously free to move through space. This included the forced movement of communities into enclaves, Bantustans, and reservations in Palestine, South Africa and North America (Turshen, 1986, Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2006, Evans-Campbell, 2008). In Skidmore’s (2003) research in Burma, control over space, beyond practical and immediate consequences, is also described as “symbolic violence and aggression” with the intent to disorient a population and engender fear and terror. Giacaman, et al. (2007b), Shalhoub-Kevorkian (2006), Pedersen, et al. (2008), Jenkins (1991), Gregory (2008), and Tol, et al. (2010) found in Palestine, Peru, El Salvador, Iraq and Nepal, constant control and surveillance of space through blockades, checkpoints, and roadblocks not only curtailed physical activities (access to health care and education, economic trade) but activities of community (interactions and creations of ease, comfort, familiarity, ownership).

Political violence changes the overall climate and functioning of communities through instilling a collective sense and generalized climate of fear, as reported in studies of political violence from Nicaragua, Colombia, Guatemala, Burma and El Salvador (Tully, 1995, Skidmore, 2003, Lykes et al., 2007, Oslender, 2007, Flores et al., 2009). Work on intergroup conflict makes clear that political violence affects collective emotional orientations, or “cultural frameworks,” such as collective fear or collective hope. The collective sense of hope is closely linked to resilience and the potential for peace in the face of political violence; in contrast, collective fear and collective hatred further entrench conflict and violence (Bar-Tal, 2001; Bar-Tal, et al., 2007). In addition to fostering the conflict, collective terror is also deliberately deployed to control populations within political violence, as research by Jenkins (1991) in El Salvador and Skidmore (2003) in Burma each concluded.

The destruction of networks that are central to the well-being of both individuals and collectives is another way in which the overall functioning of communities is threatened. Scholars of political violence in El Salvador and Argentina concluded political violence deliberately destroys relationships, social ties and networks (Martín-Baró et al., 1994, Robben, 2005). While other authors do not characterize the destruction of networks as an overt act of political violence, studies by Pedersen et al. (2008), Jones, et al. (2003), and Dillenburger et al. (2008) in Peru, Kosovo and Ireland found destruction of networks was the ultimate result.

Finally, political violence diminishes the number, and strength, of community organizations and organizing activity, as reported in research by Skidmore in Burma (2003) and Esparza (2005), Flores, et al. (2009), and Lykes, et al. (2007) in Guatemala. Increased collective resignation and passivity, defeatist thoughts about “moving forward,” and failure to speak out against further repression were reported by Pedersen, et al. in Peru (2010). In Lykes, et al.’s research in Guatemala, more than half of respondents indicated unity and social mobilization existed only a little bit or not at all (Lykes et al., 2007). Diminished organizing activity is often accomplished through targeted killings, surveillance and repression aimed at individuals or geographic areas suspected of community organizing, particularly university students and professors and community leaders, as reported by Keller, et al. (2008), Flores, et al. (2009), Skidmore (2003), Snider (2004), and Wang (2010) of political violence in Zimbabwe, Guatemala, Burma, Peru and Kosovo.

Political violence & governmental functioning

The freedom, pluralism, accountability and trust inherent within functioning democracies support individual development and well-being, particularly within cases of mass disasters such as political violence (Melton and Sianko, 2010, Garbarino, 2011). In a more practical sense, individuals depend on governmental structures to provide opportunities for meaningful participation and to fulfill of basic requirements of health and well-being, such as systems for emergency response, water, sanitation, health and schooling (Flores et al., 2009, Melton and Sianko, 2010). Political violence is intimately related to several areas of governance, including leadership, freedom of the press, and accountability by governments for atrocities (de Jong, 2010). The literature suggests that political violence deteriorates the functioning of governments and its consequent ability to support the populace in three ways: (1) by deteriorating government systems necessary for daily living, (2) by weakening the public sector, and (3) by destroying democratic processes.

Well functioning public utility systems ensure public health. Studies done in El Salvador, Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Sri Lanka and South Africa found effects of political violence include the destruction or neglect of public utility systems (sewage, electric and water) and infrastructure like roads and bridges (Yach, 1988, Ugalde et al., 2000, Reilley et al., 2002, Coward 2004, Salvage, 2007, Gregory, 2008, Hamieh and Ginty, 2010). Graham (2010) concluded attacks on physical infrastructure needed for water and electricity networks in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon and Iraq represent an underlying aim to “de-modernize” whole societies. The damage to medical systems due to political violence has a host of consequences, including increased infectious disease (Beyrer, 1998, Reilley et al., 2002, Gayer et al., 2007) and problems in vaccination services (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2003, Herp et al., 2003). Damage is incurred through deliberate targeting of or “collateral damage” to health centers, as reported by Itavyar and Ogba (1989), Farmer (2004) and Yusufzai (2008) in Africa, Haiti, and Pakistan, respectively. Pedersen (2002) reported this damage in Mozambique, Nicaragua, and Peru. Salvage (2007) reported deterioration of health systems resulting from political violence in Iraq through material destruction of clinics and a reduction in supplies, equipment and drugs necessary for healthcare provision. Medical personnel have also been explicit targets of political violence in Afghanistan, Guatemala, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, the Philippines, Iraq, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Croatia, Bosnia, Palestine and Kashmir (Garfield et al., 1987, Pedersen, 2002, Keller et al., 2008, Yusufzai, 2008, Acerra et al., 2009, Flores et al., 2009). Basu (2004), Farmer (2004) and Simunovic (2007) correlate political violence to the shortage of healthcare workers in Haiti, Iraq and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In addition to physical infrastructure for healthcare, strong and responsive governmental systems are needed for health and well-being of populations (Katz, 2001, Farmer, 2004, Pfeiffer et al., 2008). However, political violence contributes to the deterioration of public sector and governments’ ability to provide for citizenry, creating “governance voids” (Cliffe and Luckham, 2000). It draws funds away from health and social services (Sidel and Levy, 2008), and diminishes resources for health sectors, as reported by Itavyar and Ogba (1989) in research throughout Africa, by Ugalde, et al. (2000) in El Salvador, where the healthcare budget was reduced by 50%, and by Farmer (2004) in Haiti, where in 2004, the newest medical school was turned into a military base for foreign troops. De-investment in the public sector as a part of political violence has been reported by Barghouthi and Giacaman (1990) in Palestine and Hamieh and Ginty in Lebanon (2010). Iraq is an example of a country with strong investment in the public mental health system prior to the invasion that now has virtually no plan for a government system of control or regulation (Hamid and Everett, 2007). Cliffe and Luckman (2000) and Pedersen (2002) report tensions are common with outside “experts” who have little understanding of the historical and political context of the area yet take control of recovery. This usurpation of control threatens government power as it decreases coordination and increases inefficiency and corruption, as reported by Simunovic (2007), Menkhaus (2010), Giacaman, et al. (2003), Ugalde et al. (2000), and Salvage (2007) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Somalia, Palestine, El Salvador and Iraq. Some reports charge the politics of outside aid within situations of political violence go beyond tensions over “turf;” rather that aid is deliberately used within political violence to manipulate and control governments or populations and to threaten sovereignty (Giacaman et al., 2003, Jacoby and James, 2010, Menkhaus, 2010).

Representation and inclusion of populations in decision making processes of government are essential for well-being (World Health Organization, 2008). Governmental systems that uphold the principles of democracy and accountability foster individual development and nurture well-being (Melton and Sianko, 2010, Garbarino, 2011). However, political violence undermines participation, as governments are weakened due to external targeting or turn against their own citizens. The aim of political violence perpetrated by people’s own governments is often to weaken political opposition, as reported in Guatemala, Argentina and Burma (Preti, 2002, Skidmore, 2003, Robben, 2005). Political violence often leaves a state void of institutions to protect its populace. There are also numerous examples of political violence wherein state institutions are the aggressors, as reported by Lykes (2007), Menkhaus (2010) and Farwell and Cole (2001). Literature from Peru, former Yugoslavia, El Salvador and Guatemala reveals the high prevalence and effects of governments’ denial of atrocities and lack of accountability for the wrong-doings during political violence in these locations (Martín-Baró et al., 1994, Preti, 2002, Basoglu et al., 2005a, Lykes et al., 2007).

Discussion

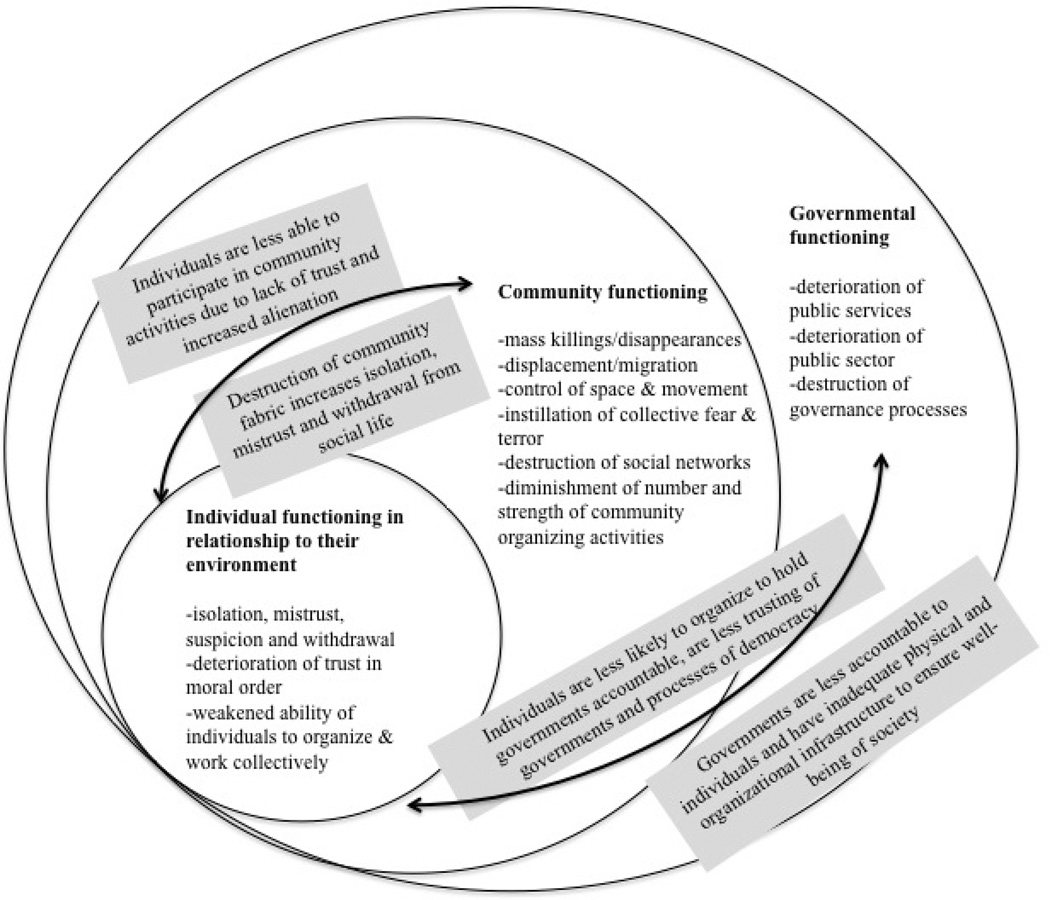

This review summarized literature on the effects of political violence, emphasizing the ways in which it impairs and dismantles collective functioning, which in turn threatens individual well-being. Findings were discussed with respect to how political violence affects an individual’s ability to participate in social and political life; how community functioning is lessened; and how the functioning of government and its official bodies is undermined. Figure 2 illustrates the effects of political violence in each domain of inquiry, following the findings detailed in the review and seen in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Effects of political violence on domains of collective functioning

Findings of various studies suggest well-being across domains is interdependent; often the weakening of one area (for instance, governmental functioning) affects another in turn (for instance, individuals’ willingness to engage in political life) (Figure 2). Studies by Robben (2005) and Skidmore (2003) found that, as individuals are less able to act as part of a collective due to mistrust and isolation stemming from political violence, community functioning suffers. Individuals are less able to take part in community activities like organizing. Lykes, et al. (2007) found that, as community functioning deteriorates (due to displacement, fear and terror, and destruction of social networks), isolation and mistrust increases. Additionally, Esparza (2005) found that, as individuals become less willing to hold governments accountable and are less trusting of governments and processes of democracy, government functioning deteriorates. Governments are also less accountable to individuals and have inadequate physical and organizational infrastructure to ensure well-being of society (Ugalde et al., 2000).

While most of these studies detailed the negative effects of political violence, one alternative hypothesis that should be presented is the notion that political violence might actually incite positive growth to the benefit of the collective, as it encourages what has been referred to on the individual level as “post-traumatic growth” (Linley & Joseph, 2004). For instance, scholars have noted that political violence inspires communities to come together for the purposes of resistance and collective demands for justice and accountability; thus, particularly in the responses, political violence may increase political involvement and build both individual and collective empowerment (Lykes, 2007; Punamäki,1990; Stewart, J., 2008). In addition, as noted in the introduction, political violence and structural violence are quite intertwined, usually co-occurring and sometimes co-precipitating. Further research is needed to determine how they interact and which might be the driving force of the collective injury within the context of political violence, and therefore perhaps the most salient point of intervention (see, for instance, Miller et al., 2010).

Implications for Further Research

Findings of this review provide implications for research. Specifically, there is a need to (1) examine health effects of political violence across multiple, interdependent areas of influence, (2) collect and refine indicators of collective functioning, especially those that may be effected by political violence, and (3) continue to develop and improve multilevel conceptual models that represent the diverse effects of political violence on health across and within levels. These are discussed below and then implications for policy and practice are explored.

First, the notion that areas of influence interact with one another is in line with theories that assert well-being rests on the mutual exchange between a person and his or her environment (Brofenbrenner and Morris, 1998, in (Brofenbrenner and Evans, 2000)). This theory of mutual exchange between person and their environment also resonates with scholars of political violence who assert it acts on multiple areas simultaneously (Martinez and Eiroa-Orosa, 2010). Thus, research frameworks that examine simultaneous consequences of violence within multiple areas of influence will provide more nuanced understandings of political violence (for expanded discussions and examples of this, see Evans-Campbell, 2008, Cummings et al., 2009, Dubow et al., 2010, Panter-Brick, 2010, Tol et al., 2010, as well as the 2010 special issue of Social Science and Medicine on conflict and health).

Second, future studies should seek to develop or refine indicators of collective functioning. Findings from this literature review suggest indicators of functioning relevant to understanding the problem of political violence on levels beyond the individual (de Jong, 2010). Creating, testing and refining measures of the areas of collective functioning on which political violence would be a useful next step in understanding the problem. Table 3 provides suggestions to this end.

Table 3.

Conceptualizing indicators of collective functioning

| Participation in social & political life |

Community Functioning & Social Fabric |

Governmental Functioning |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Third, this paper provides a preliminary conceptual model for identifying some of the effects of political violence on relationships between domains of collective functioning that underlie health. Future research might investigate this further and refine conceptual models that examine the effects of political violence on mutually created domains of collective functioning. It would be of particular use if these models or future research on political violence examined the relationship between community functioning/social fabric and governmental functioning, as this review of the literature did not find studies that proposed or explored this relationship. Research might also add domains, such as family functioning, to models of collective effects of political violence (Garbarino and Kostelny, 1996, Qouta et al., 2006, Haj-Yahia, 2007). Future models might also take a more positive focus and attend to resiliency or protective factors within political violence across multiple levels of functioning, as sociocultural processes, community resilience, and civic and political engagement all appear to build endurance in the face of political violence (Jenkins, 1991; Qouta et al., 1995; Khamis, 1998; Barber, 2001; Norris et al., 2008; Nguyen-Gillham et al., 2008; Nuwayhid et al., 2011; Sousa, et al., 2013; Zraly and Nyirazinyoye, 2010).

Findings from this review suggest a few implications for policy and practice. In light of the far-reaching effects of political violence demonstrated in this review and elsewhere, prevention of political violence itself should be prioritized, as pointed out by other health scholars (Hagopian et al., 2009, de Jong, 2010). In terms of secondary or tertiary prevention, or recovery from or management of effects of political violence, an increase in knowledge of the collective effects of political violence is particularly salient for mental health professionals focusing on conflict zones. Researchers have suggested sound collective social and political functioning plays a positive, protective role in the mental health of those who have experienced political violence (Farwell and Cole, 2001, de Zulueta, 2007). Equally important is the ability of individuals to aid in the rebuilding of social and political arenas of their societies after political violence through active participation, which necessitates trust and the ability to work collectively (Hernández, 2002). Understanding, then, how political violence affects both individuals and the social and political systems on which their health and well-being depend will help us to identify potential targets for multilevel policy and practice interventions (for examples of this, see Robben, 2005, Laplante and Holguin, 2006, Hoffman and Kruczek, 2011).

Recovery from the effects of political violence happens not only in the world of the individual, but also in their social and political worlds (Almedom and Summerfield, 2004). By focusing on political violence and collective well-being, this review illustrates the potential for multilevel frameworks that move beyond individual pathology to develop more nuanced conceptualizations of the health problems resulting from political violence. This increased understanding holds the potential to help to develop and implement treatment, intervention and prevention programs and policies that address the influence of political violence on health across multiple levels of functioning.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Drs. Todd Herrenkohl, Susan Kemp, Taryn Lindhorst, David Takeuchi, Tracy Harachi and Amy Hagopian for their thorough edits and thoughtful assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Acerra JR, Iskyan K, Qureshi ZA, Sharma RK. Rebuilding the health care system in Afghanistan: an overview of primary care and emergency services. International journal of emergency medicine. 2009;2:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s12245-009-0106-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agaibi CE. Trauma, PTSD, and Resilience: A Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6(3):195–216. doi: 10.1177/1524838005277438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Gasseer N, Dresden E, Keeney GB, Warren N. Status of women and infants in complex humanitarian emergencies. Journal of midwifery & women’s health. 2004;49(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almedom AM, Summerfield D. Mental well-being in settings of ‘complex emergency’: an overview. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2004;36:381–388. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Political Violence, Social Integration, and Youth Functioning: Palestinian Youth from the Intifada. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Contrasting portraits of war: Youths’ varied experiences with political violence in Bosnia and Palestine. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:298. [Google Scholar]

- Barghouthi M, Giacaman R. The emergence of an infrastructure of resistance: The case of health. In: Nassar J, Heacock R, editors. Intifada: Palestine at the crossroads. New York: Praeger; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D. Why Does Fear Override Hope in Societies Engulfed by Intractable Conflict, as It Does in the Israeli Society? Political Psychology. 2001;22(3) [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D, Halperin E, de Rivera J. Collective Emotions in Conflict Situations: Societal Implications. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63(2):441–460. [Google Scholar]

- Basoglu M, Livanou M, Crnobaric C. Psychiatric and Cognitive Effects of War in Former Yugoslavia: Association of Lack of Redress for Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Reactions. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005a;294:580–590. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basoglu M, Livanou M, Crnobaric C, Franciskovic T, Suljic E, Duric D, Vranesic M. Psychiatric and Cognitive Effects of War in Former Yugoslavia: Association of Lack of Redress for Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Reactions. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005b;294:580. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basoglu M, Livanou M, Crnobaric C, Franciskovic T, Suljic E, Duric D, Vranesic M. Psychiatric and Cognitive Effects of War in Former Yugoslavia: Association of Lack of Redress for Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Reactions. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005c;294:580. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu P. Iraq’s public health infrastructure a casualty of war. Nature medicine. 2004:10. doi: 10.1038/nm0204-110a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JA, Woods NF. Global Women’s Health: A Spotlight on Caregiving. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2009;44(3):375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk JH. Trauma and resilience during war: a look at the children and humanitarian aid workers of Bosnia. Psychoanalytic Review. 1998;85:640–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s Former Child Soldiers: A Longitudinal Study of Risk, Protective Factors, and Mental Health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry. 2008;20:317–328. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C. Burma and Cambodia: Human Rights, Social Disruption, and the Spread of HIV/AIDS. Health and Human Rights. 1998;2:84–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum W. Rogue state: A guide to the world’s only superpower. Monroe, Me.: Common Courage Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? The American Psychologist. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brofenbrenner U, Evans GW. Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social Development. 2000;9:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E, Darby J. The conflict in Northern Ireland: Causes, consequences, and controls. [10.1037/0003-066X.53.7.754] American Psychologist. 1998;53(7):754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo M, Smajkic A, Zeric D, Dzidowska M, Gebre-Medhin JOY, Van Halem J. Mental health and coping in a war situation: The case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2004;36:463–477. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Cdc) Vaccination services in postwar Iraq. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52:734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaskin RJ. Perspectives on neighborhood and community: A review of the literature. In: Tropman JE, Erlich J, Rothman J, editors. Tactics & techniques of community intervention. Itasca, Ill.: F.E. Peacock Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe L, Luckham R. What Happens to the State in Conflict?: Political Analysis as a Tool for Planning Humanitarian Assistance. Disasters. 2000;24:291–313. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward M. Urbicide in Bosnia. In: Graham S, editor. Cities under siege: The new military urbanism. London; New York: Verso; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings ME, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Merrilees CE, Cairns E. Children and Political Violence from a Social Ecological Perspective: Implications from Research on Children and Families in Northern Ireland. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:16–38. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JTVM. A public health framework to translate risk factors related to political violence and war into multi-level preventive interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JTVM, Komproe IH, van Ommeren MV. Common mental disorders in postconflict settings. The lancet. 2003:2128–2130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong K, Ford N, Lokuge K, Fromm S, Van Galen R, Reilley B, Kleber R. Conflict in the Indian Kashmir Valley II: psychosocial impact. Conflict and Health. 2008:2. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong K, Mulhern M, Ford N, Simpson I, Swan A, Van Der Kam S. Psychological trauma of the civil war in Sri Lanka. The Lancet. 2002;359:1517–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zulueta CF. Mass violence and mental health: Attachment and trauma. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19:221–233. doi: 10.1080/09540260701349464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillenburger K, Fargas M, Akhonzada R. Long-Term Effects of Political Violence: Narrative Inquiry Across a 20-Year Period. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1312–1322. doi: 10.1177/1049732308322487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, Boxer P, Shikaki K, Landau S, Gvirsman SD, Ginges J. Exposure to conflict and violence across contexts: Relations to adjustment among Palestinian children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:103–116. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulic T. Mass killing in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945: a case for comparative research. Journal of Genocide Research. 2006;8:255–281. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman L, Kersner D, Kordon D, Lagos D. Psychosocial effects and treatment of mass trauma due to sociopolitical events: The Argentine experience. In: Krippner S, McIntyre TM, editors. The psychological impact of war trauma on civilians : an international perspective: Psychological dimensions to war and peace. Westport, Conn.: Praeger; 2003. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza M. Post-war Guatemala: long-term effects of psychological and ideological militarization of the K’iche Mayans. Journal of Genocide Research. 2005;7:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T. Historical Trauma in American Indian/Native American Communities: A Multilevel Framework for Exploring Impacts on Individuals, Families, and Communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, Keshavjee S. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(10):e449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. Political Violence and Public Health in Haiti. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:1483–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farwell N, Cole JB. Community as a Context of Healing Psychosocial Recovery of Children Affected by War and Political Violence. International Journal of Mental Health. 2001;30:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman A. Political Terror and the Technologies of Memory: Excuse, Sacrifice, Commodification, and Actuarial Moralities. Radical History Review. 2003;85:58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Flores W, Ruano AL, Funchal DP. Social Participation within a Context of Political Violence: Implications for the Promotion and Exercise of the Right to Health in Guatemala. Health and Human Rights. 2009;11:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove MT. Psychiatric implications of displacement: contributions from the psychology of place. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:1516–1523. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtung J. Violence, peace and peace research. Journal of Peace Research. 1969;6(3):167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. What does living in a democracy mean for kids? The American journal of orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:443–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Dubrow N, Kostelny K, Pardo C. Children in Danger. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Kostelny K. The effects of political violence on Palestinian children’s behavior problems: a risk accumulation model. Child Dev Child Development. 1996;67:33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RM, Frieden T, Vermund SH. Health-related outcomes of war in Nicaragua. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:615–618. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.5.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayer M, Legros D, Formenty P. Conflict and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13:1625–1631. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.061093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R, Abdul-Rahim HF, Wick L. Health sector reform in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT): targeting the forest or the trees? Health Policy and Planning. 2003;18:59–67. doi: 10.1093/heapol/18.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R, Husseini A, Gordon NH, Awartani F. Imprints on the consciousness. European Journal of Public Health. 2004;14:286–290. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R, Mataria A, Nguyen-Gillham V, Abu Safieh R, Stefanini A, Chatterji S. Quality of life in the Palestinian context: An inquiry in war-like conditions. Health Policy. 2007a;81:68–84. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R, Mataria A, Nguyen-Gillham V, Safieh RA, Stefanini A, Chatterji S. Quality of life in the Palestinian context: An inquiry in war-like conditions. Health Policy. 2007b;81:68–84. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R, Shannon H, Saab H, Arya N, Boyce W. Individual and collective exposure to political violence: Palestinian adolescents coping with conflict. European Journal of Public Health. 2007c;17:361–368. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. Introduction. In: Graham S, editor. Cities under siege : the new military urbanism. London; New York: Verso; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. Cities under siege: The new military urbanism. London; New York: Verso; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory D. The Biopolitics of Baghdad: Counterinsurgency and the Counter-City. Human Geography. 2008:1. [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian A, Ratevosian J, Deriel E. Gathering in groups: peace advocacy in health professional associations. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009:84. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181baa21b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Yahia MM. Challenges in studying the psychological effects of Palestinian children’s exposure to political violence and their coping with this traumatic experience. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Yahia MM. Political violence in retrospect: Its effect on the mental health of Palestinian adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid HI, Everett A. Developing Iraq’s mental health policy. Psychiatric services. 2007;58:1355–1357. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamieh CS, Ginty RM. A very political reconstruction: governance and reconstruction in Lebanon after the 2006 war. Disasters. 2010;34:103–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández P. Resilience in Families and Communities: Latin American Contributions From the Psychology of Liberation. The Family Journal. 2002;10:334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Herp MV, Parqué V, Rackley E, Ford N. Mortality, Violence and Lack of Access to Healthcare in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Disasters. 2003;27:141–153. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Watson P, Bell CC, Bryant RA, Brymer MJ, Friedman MJ, Friedman M, Gersons BPR, De Jong JT, Layne CM, Maguen S, Neria Y, Norwood AE, Pynoos RS, Reissman D, Ruzek JI, Shalev AY, Solomon Z, Steinberg AM, Ursano RJ. Five Essential Elements of Immediate and MidTerm Mass Trauma Intervention: Empirical Evidence. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2007;70:283–315. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M, Kruczek T. A Bioecological Model of Mass Trauma: Individual, Community, and Societal Effects Œ∑. The Counseling Psychologist. 2011;39:1087–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Ityavyar DA, Ogba LO. Violence, conflict and health in Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 1989;28:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby T, James E. Emerging patterns in the reconstruction of conflict-affected countries. Disasters. 2010;34:S1–S14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH. The state construction of affect: political ethos and mental health among Salvadoran refugees. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1991;15:139–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00119042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. Adolescent understandings of political violence and psychological well-being: A qualitative study from Bosnia Herzegovina. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1351–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Kafetsios K. Exposure to Political Violence and Psychological Well-being in Bosnian Adolescents: A Mixed Method Approach. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;10:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Rrustemi A, Shahini M, Uka A. Mental health services for war-affected children: report of a survey in Kosovo. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2003;183:540–546. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MB. The price of citizenship : redefining the American welfare state. New York: Metropolitan Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Keller AS, Stewart SA, Eppel S. Health and human rights under assault in Zimbabwe. Lancet. 2008;371:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp SP. Place matters: Towards a rejuvenated theory of environment for direct social work practice. In: Borden W, editor. The place and play of theory in social work practice. New York: Columbia University Press; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp SP, Whittaker JK, Tracy EM. Person-environment practice: The social ecology of interpersonal helping. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Khamis V. Psychological distress and well-being among traumatized Palestinian women during the intifada. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;46:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:668–677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Proximal, Distal, and the Politics of Causation: What’s Level Got to Do With It? American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:221–230. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante LJ, Holguin MR. The Peruvian Truth Commission’s Mental Health Reparations: Empowering Survivors of Political Violence to Impact Public Health Policy. Health and human rights. 2006;9:136–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley P, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(1):11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low SM, Altman I. Place attachment: A conceptual inquiry. In: Altman I, Low SM, editors. Place attachment: Human behavior and environment. Vol. 12. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lykes MB. Activist participatory research among the Maya of Guatemala: Constructing meanings from situated knowledge. GSOI Journal of Social Issues. 1997;53:725–746. [Google Scholar]

- Lykes MB, Beristain CM, Perez-Armioan MLC. Political Violence, Impunity, and Emotional Climate in Maya Communities. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63:369–385. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Major episodes of political violence 1946–2010 [online] [Accessed Access Date 2010];Center for Systematic Peace. 2010 Available from: http://www.systemicpeace.org/warlist.htm.

- Martín-Baró I, Aron A, Corne S. Writings for a liberation psychology. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez MA, Eiroa-Orosa FJ. Psychosocial research and action with survivors of political violence in Latin America: methodological considerations and implications for practice. Intervention. 2010;8:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2(4):425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Obradovic J. Disaster Preparation and Recovery: Lessons from Research on Resilience in Human Development. Ecology & Society. 2008;13(1) [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Narayan AJ. Child Development in the Context of Disaster, War, and Terrorism: Pathways of Risk and Resilience. [10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100356] Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63(1):227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton GB, Sianko N. How can government protect mental health amid a disaster? The American journal of orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:536–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkhaus K. Stabilisation and humanitarian access in a collapsed state: the Somali case. Disasters. 2010;34:320–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina N, Ford JD. Complex sequelae of psychological trauma among Kosovar civilian war victims. The International journal of social psychiatry. 2008;54:425–436. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM. Writing an Effective Review Article. [10.1007/s13181-012-0234-2] Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2012;8(2):89–90. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BS. Post-War Trauma and Reconciliation in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Observations, Experiences, and Implications for Marriage and Family Therapy. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2003;31:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Gillham V, Giacaman R, Naser G, Boyce W. Normalising the abnormal: Palestinian youth and the contradictions of resilience in protracted conflict. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2008;16:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris F, Stevens S, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche K, Pfefferbaum R. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell B, Boyd N. Viewing community as responsibility as well as resource: deconstructing the theoretical roots of psychological sense of community. Journal of community psychology. 2010;38:828. [Google Scholar]

- Nuwayhid I, Zurayk H, Yamout R, Cortas CS. Summer 2006 war on Lebanon: A lesson in community resilience. Global Public Health. 2011;6:505–519. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.557666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslender U. Spaces of terror and fear on Colombia’s Pacific Coast. In: Gregory D, Pred A, editors. Violent geographies: fear, terror, and political violence. New York: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C. Conflict, violence, and health: Setting a new interdisciplinary agenda. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen D. Political violence, ethnic conflict, and contemporary wars: broad implications for health and social well-being. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:175–190. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen D, Kienzler H, Gamarra J. Llaki and Ñakary: Idioms of Distress and Suffering Among the Highland Quechua in the Peruvian Andes. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2010;34:279–300. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen D, Tremblay J, Errazuriz C, Gamarra J. The sequelae of political violence: Assessing trauma, suffering and dislocation in the Peruvian highlands. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer J, Johnson W, Fort M, Shakow A, Hagopian A, Gloyd S, Gimbel-Sherr K. Strengthening health systems in poor countries: a code of conduct for nongovernmental organizations. American journal of public health. 2008;98:2134–2140. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti A. Guatemala: Violence in Peacetime - A Critical Analysis of the Armed Conflict and the Peace Process. Disasters. 2002;26:99–119. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki R-L. Relationships between political violence and psychological responses among Palestinian women. Journal of peace research. 1990;271:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamaki R-L, El Sarraj E. The impact of the peace treaty on psychological well-being: A follow-up study of Palestinian children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00080-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, PunamaäKi RL, El Sarraj E. Mother-child expression of psychological distress in war trauma. SAGE Family Studies Abstracts. 2006:28. [Google Scholar]

- Reilley B, Abeyasinghe R, Pakianathar MV. Barriers to prompt and effective treatment of malaria in northern Sri Lanka. Tropical medicine & international health. 2002;7:744–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robben ACGM. Political violence and trauma in Argentina. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Salvage J. Casualties of war. Nursing standard. 2007:21. doi: 10.7748/ns.21.50.20.s24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. The neighborhood context of well-being. IPBM Perspectives in Biology & Medicine. 2003;46:S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, editors. Taking stock : the status of criminological theory. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and Designing Mixed Research Synthesis Studies. Research in the schools. 2006;1329(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal R, Weizman E, Tartakover D. A civilian occupation : the politics of Israeli architecture. Tel Aviv; London; New York: Babel; VERSO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shalhoub-Kevorkian N. Counter-Spaces as Resistance in Conflict Zones: Palestinian Women Recreating a Home. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy. 2006;17:109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Toohey SM. Community Contexts of Human Welfare. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidel VW, Levy BS. The health impact of war. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008;15:189–195. doi: 10.1080/17457300802404935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunovic VJ. Health care in Bosnia and Herzegovina before, during, and after 19921995 war: a personal testimony. Conflict and health. 2007:1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore M. Darker than Midnight: Fear, Vulnerability, and Terror Making in Urban Burma (Myanmar) American Ethnologist. 2003;30:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Snider L, Cabrejos C, Huayllasco Marquina E, Jose Trujillo J, Avery A, Ango Aguilar H. Psychosocial assessment for victims of violence in Peru: The importance of local participation. Journal of biosocial science. 2004;36:389–400. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa C, Haj-Yahia MM, Feldman G, Lee J. Political violence and resilience. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. doi: 10.1177/1524838013493520. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]