Abstract

Clinical, neuroimaging, and neuropathological findings of 2 cases of canine primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis are described. Magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of the brain revealed diffuse leptomeningeal alterations with no parenchymal involvement. These cases share many similarities with the same disease in humans.

Résumé

Gliomatose leptoméningée diffuse primaire chez 2 chiens. Les constatations cliniques ainsi que les résultats de la neuroimagerie et de la neuropathologie de 2 cas de gliomatose leptoméningée diffuse primaire sont décrits. L’imagerie par résonance magnétique et l’examen histopathologique du cerveau ont révélé des altérations leptoméningées sans atteinte parenchymateuse. Ces cas partagent beaucoup de similitudes avec la même maladie chez les humains.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Leptomeningeal gliomatosis is an uncommon, fatal condition reported in humans. It is characterized by widespread seeding of gliomatous tumor cells in the subarachnoid space (1). It includes a primary and a secondary form. The primary form, also known as primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis (PDLG), is a rare condition arising from heterotopic glial nests without evidence of tumor within the parenchyma of the brain and spinal cord (1). In the secondary form, leptomeningeal neoplastic invasion comes from a central nervous system (CNS) parenchymal focus of glial origin (1). Diagnosis requires histopathological confirmation. In the absence of histopathology, the diagnosis is based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance and exclusion of other diseases (2). Diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement with no discernible intra-axial component is a relevant finding in PDLG (1,2). However, in spite of the diagnostic usefulness of imaging and consequent leptomeningeal biopsy, PDLG in human medicine remains a difficult antemortem diagnosis (1–5).

In veterinary medicine, diffuse cranial meningeal involvement without parenchymal lesions is reported in dogs affected by leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, a secondary dissemination through the subarachnoid space from a solid tumor (6,7), or by idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis, a non-specific inflammatory and fibrotic disease of the dura mater (8). To the authors’ knowledge, primary leptomeningeal gliomatosis, as a single entity, has never been documented in companion animals. In this study, clinical, neuroimaging, and neuropathological findings of PDLG in 2 dogs are reported.

Case descriptions

Case 1

An 8-year-old male boxer dog was presented with a 4-month history of depressed mental status, progressive gait abnormalities, behavioral changes, and cervical pain. The dog had been previously treated with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug without any improvement in clinical signs.

A general physical examination detected no abnormalities. Neurological examination revealed depressed mental status, bilateral incomplete menace response, non-ambulatory tetraparesis, and decreased proprioception in all 4 limbs. The rest of the neurological examination was unremarkable. A diffuse or multifocal brain lesion was localized, with a suspected severe brainstem involvement. The main differential diagnoses were: meningoencephalitis of unknown etiology; bacterial, viral, protozoan, or fungal meningoencephalitis; uremic or hepatic encephalopathy, electrolyte imbalances, thiamine deficiency; and primary or secondary neoplasms. Results of complete blood (cell) count (CBC), serum biochemistry, and urinalysis were within normal ranges. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and cervical spinal cord was performed with a 0.22 T unit (MrV; Paramed, Genova, Italy). T1-weighted, post contrast [0.1 mmol/kg gadoteric acid IV (Dotarem; Gurbet Laboratories, Milan, Italy)] T1-weighted, and T2-weighted images were acquired in transverse, dorsal, and sagittal planes. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed dilation of the entire ventricular system (Figures 1A, B). At the level of the pons and medulla oblongata, the meninges appeared diffusely thickened and hyperintense on T2-weighted images with a marked contrast enhancement on postcontrast T1-weighted images (Figure 1A). The cervical region showed an intramedullary lesion, homogeneously hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The lesion had a transverse maximal width of 4.6 mm and extended from the second to the seventh cervical vertebral bodies. It was interpreted as an extensive syringohydromyelia. Neither intraparenchymal involvement, nor apparent signs of tentorial or foramen magnum herniation were seen. Clinical and MRI findings were suggestive of either meningitis or a disseminated, primary or secondary, meningeal neoplasm. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tap was not performed due to cardiovascular complications during the anesthesia (low systemic arterial pressure and heart rate: systolic pressure 30 mmHg; heart rate 20 bpm). During the following 2 d, treatment of the obstructive hydrocephalus consisted of diuretics [furosemide (Furosemide Italfarmaco, Italfarmaco SpA, Milan, Italy)] 1 mg/kg body weight (BW), IV, q12h and corticosteroids (prednisolone; Novosterol, Ceva Vetem SpA, Monza, Italy) 0.5 mg/kg BW, SC, q12h. Despite treatment, the patient’s neurological condition progressed to a stuporous mental state, non-ambulatory tetraparesis with absence of proprioception in all 4 limbs, and the owner elected euthanasia. A complete postmortem examination was performed.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance images (A,B) from Case 1. A — Transverse postcontrast T1-weighted (TE 24 ms; TR 690 ms) image at the level of the medulla oblongata. B — Dorsal postcontrast T1-weighted (TE 24 ms; TR 620 ms) image at the level of the fourth ventricle. Note dilation of the lateral and fourth ventricles (arrows, Figures 1A,1B) and widespread enhancement of the meninges of the medulla oblongata (arrowheads, Figure 1A). C — Irregular and gelatinous leptomeningeal thickening in the rhomboencephalic ventral surface (arrows). The orientation left/right was flipped to facilitate comparison with MRI images.

At gross examination a marked diffuse thickening of the brainstem leptomeninges produced a whitish capsule-like feature (Figure 1C). It was more remarkable in the ventral surface of both the cerebellar-pontine angle and the medulla oblongata. Hydrocephalus and dilation of the central canal of the cervical spinal cord were confirmed. On histological examination, central canal dilation was associated with small dorsolateral fluid-filled cavitations lined by glial cells. These findings were consistent with syringohydromyelia. Histologically, the rhomboencephalic leptomeninges showed a diffuse infiltration of atypical cells with small round hyperchromatic nuclei and a large perinuclear halo with well-defined borders. The neoplastic cells were arranged in nests and lobules defined by a fine fibrovascular stroma and formed a small mass at the level of the ventral mesencephalic leptomeninges (Figure 2A). The mitotic index was high (16 mitotic figures/10 HPF). A slight infiltration of tumor cells was observed superficially at the parahippocampal gyrus and at the ventral thalamus, where it involved the adjacent optic nerves. Occasionally, neoplastic cells infiltrated the subpial thalamic and mesencephalic parenchyma, often in perivascular spaces. A fibroblastic hyperplasia and an increased number of small blood vessels were also observed. Selected paraffin-embedded brain sections were submitted to avidin-biotin peroxidase complex staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1:500; Dako, Carpenteria, California, USA), Olig2 (Olig2, rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1:50; Chemicon, Milan, Italy), MAC387 (MAC387, mouse monoclonal antibody anti-human myeloid/histiocyte antigen, 1:40; Dako), and lysozyme (rabbit anti-human lysozyme, 1:50; Dako). At immunolabelling, the neoplastic cells were diffusely immunoreactive for Olig2 (Figure 2B). Occasional infiltrating cells were GFAP-positive. Isolated MAC387 and lysozyme-positive cells were also identified throughout the meninges. Based on pathological findings a PDLG of oligondendrocytic origin was diagnosed.

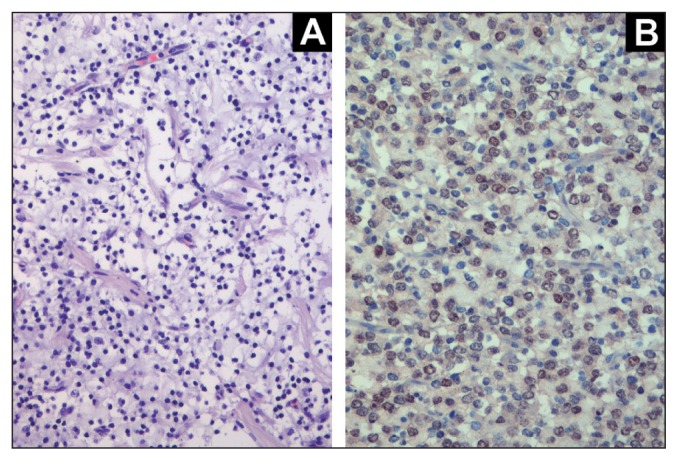

Figure 2.

Histological and immunohistochemical features of Case 1. A — Mesencephalic leptomeningeal mass characterized by round well-defined neoplastic cells, with hyperchromatic nuclei and perinuclear halo [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)] (×40). B — Olig2-immunoreaction is expressed as a nuclear pattern in about 80% of the neoplastic cells (anti-Olig2 antibody, ABC IHC-method, Carazzi’s counterstain, ×40).

Case 2

A 9-year-old male boxer dog was presented with a 2-week history of gait abnormalities and depressed mental status. A general physical examination detected no abnormalities, whereas neurological examination revealed a severely depressed mental status, right circling, lack of menace response and cotton ball test in the right eye, decreased menace response and palpebral reflex in the left eye, and left facial paresis. The rest of the neurological examination was unremarkable. Clinical signs were consistent with a multifocal localization. The main differential diagnoses were the same as for case 1. Results of CBC, serum biochemistry and urinalysis were within normal ranges.

An MRI study of the brain was performed using the same protocol as in case 1. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images of the brain, in the transverse plane, were also acquired. The entire ventricular system was dilated. On FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences, the meninges appeared diffusely hyperintense. On postcontrast T1-weighted images, a markedly enhanced meningeal thickening at the level of brainstem, cerebellar-pontine angles, interthalamic adhesion, and right cerebrum was seen (Figures 3A, B). The lesion appeared entirely extra-axial and no obvious signs of parenchymal infiltration were seen. Analysis of CSF, collected from the cerebellomedullary cistern, revealed elevated total protein [1.0 g/L; reference range (RR): < 0.25 g/L], and a normal cell count (1 nucleated cell/μL; RR: 0 to 5 nucleated cells/μL), consistent with albuminocytological dissociation. Due to the poor prognosis, the owner requested euthanasia and a complete postmortem examination was authorized.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance images (A,B) for Case 2. A — Transverse postcontrast T1-weighted (TE 24 ms; TR 644 ms) image at the level of diencephalomesencephalic junction. B — Dorsal postcontrast T1-weighted (TE 24 ms; TR 620 ms) image at the level of the temporal area. There are multifocal contrast enhancing lesions (arrows) involving mostly the meninges at the level of the transition between diencephalon and mesencephalon (Figure 2A) and at the level of mesencephalon, third ventricle, interthalamic adhesion, and right prosencephalon (Figure 2B). C — A brownish mass dramatically disfigures the diencephalomesencephalic profile (arrows). The orientation left/right was flipped to facilitate comparison with MRI images.

Macroscopic examination of the brain showed a diffuse leptomeningeal thickening, due to a brownish gelatinous tissue. It was more severe at the level of the thalamus and mesencephalon where it was associated with a pale halo (Figure 3C). Histologically, the subarachnoid space was widely infiltrated by round-oval to fusiform-shaped cells showing long cytoplasmic processes, with hyperchromatic large nuclei (Figure 4A). Mitotic figures were > 20/10 HPF. A significant increase in the number of blood vessels was also evident. As the tumor progressed from the prosencephalon to the rhomboencephalon, it was associated with a diffuse subpial superficial neoplastic invasion of the adjacent nervous tissue. Selected paraffin-embedded brain sections were submitted to avidin-biotin peroxidase complex staining for GFAP, Olig2, MAC387, and lysozyme as described in case 1. The neoplastic cells were diffusely and markedly GFAP-positive (Figure 4B). Scattered MAC387 and lysozyme-positive cells were found, while Olig2 positive cells were not observed. In this case a PDLG of astrocytic origin was diagnosed.

Figure 4.

Histological and immunohistochemical features of Case 2. A — Neoplastic cells infiltrating brain leptomeninges arranged in a storiform pattern (H&E, ×40). B — Neoplastic fusiform cells infiltrating brain leptomeninges have long GFAP-positive cytoplasmic processes (anti-GFAP antibody, ABC IHC-method, Carazzi’s counterstain, ×40).

Discussion

Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis, thought to be a neoplastic transformation of heterotopic glial nests, is a rare condition first described in humans by Roussy et al in 1923 (9). During development, these heterotopic cells are thought to migrate from the CNS through microscopic defects in the pia mater (1). Diffuse, neoplastic involvement of the leptomeninges has rarely been reported in veterinary medicine, as a form of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis (6,7), or secondary to a primary intraparenchymal glioma or gliomatosis (10,11). To the authors’ knowledge PDLG, as a single entity, has never been described in the veterinary literature. This is the first report describing such a condition in dogs.

The cases reported herein share many similarities with human PDLG (1,3–5,12,13). The symptomatology of human PDLG is non-specific, mainly suggesting raised intracranial pressure (ICP) and complicated by hydrocephalus due to obstruction of CSF drainage (1,4,5). The most common findings are meningeal signs, mental confusion, headaches, and multiple cranial palsies. Due to the lack of specificity and the variability of clinical presentation, the clinical diagnosis of these tumors poses a difficult challenge and encompasses the differential diagnoses of chronic/subacute meningitis, of infectious, autoimmune etiology and neoplasms (1,4,5). Similarly, the clinical signs exhibited by these 2 dogs were poorly localized, reflecting the diffuse nature of the disease, and were probably related to the suspected raised ICP secondary to the obstruction of CSF drainage in the subarachnoid space. Also in our cases, the main differential diagnoses were inflammatory or neoplastic diseases.

In human medicine, MRI is the most accurate diagnostic imaging modality for leptomeningeal pathology in the CNS, with a higher sensitivity than computed tomography (2,14). Diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement with no discernible intra-axial component is a consistent finding in PDLG cases (1,3,4). FLAIR sequences are particularly useful in depicting the extent of the disease, showing diffuse hyperintense signal in the subarachnoid space (1). Markedly elevated protein content and occupation of subarachnoid space by neoplastic cells may contribute to this phenomenon (1). Consistent with what has been reported in human medicine, FLAIR sequences in case 2 allowed a further identification of the disease showing diffuse hyperintensity of the brainstem meninges. Moreover, in both our cases, MRI showed diffuse meningeal enhancement in cerebral hemispheres, thalamus and brainstem, with no evidence of intraparenchymal involvement, and an obstructive hydrocephalus.

In human cases, CSF assay usually shows an elevation in proteins associated with low or moderate pleocytosis and normal or low glucose levels (1,13,15). Repetitive CSF collection and analysis may be needed for proper diagnosis even if the first tap failed to prove the existence of neoplastic cells. Despite diffuse leptomeningeal involvement, neoplastic cells are held together due to their adhesive nature with a meshwork of cell processes; therefore, they are less prone to exfoliate (1,5). Likewise, in case 2 CSF analysis revealed an albuminocytological dissociation and no malignant cells were found.

Although a number of cases have been reported in human medicine since 1923 (9), PDLG is not recognized as a specific neoplastic entity by the World Health Organization in classification of tumors of the CNS, but it is considered in the differential diagnoses of gliomatosis along with gliomatosis cerebri and gliomatosis peritonei (16). Histological classification of PDLG, therefore, follows the conventional classification of gliomas.

It has been hypothesized that PDLG arises within heterotopic leptomeningeal glial nests, which can be found in the subarachnoid space in approximately 1% of random necropsies, most commonly around the medulla oblongata (17). Involvement of the medulla oblongata in both our cases seems to support this pathogenesis in dogs. Nevertheless, a number of localizations of the lesions other than in the brainstem have been reported in the human literature, including cerebrum, cerebellum, spinal cord, and cauda equina (3–5). Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis can develop as a nodular or as a diffuse form. The nodular form is also recognized as a solitary or focal leptomeningeal gliomatosis, defined by limited tumor masses in the cranial or spinal leptomeninges (12). On the contrary, the latter is considered as a diffuse extension, outside the parenchyma, of glial tumor cells over a wide area of the CNS (18), which corresponds to our observations. Moreover, recently leptomeningeal gliomatosis was redefined as a neoplasm, although largely leptomeningeal, associated with a parenchymal component small enough to be considered as an ingrowth from the meningeal lesion (19). This condition might be considered for case 2.

Regarding histological classification, PDLG of astrocytic origin is more common in humans than the oligodendrocytic form (1,3,4). Uncommonly PDLG has been considered consistent with ganglioglioma and ependymoblastoma (1,5). In our study, histopathological and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with oligodendrocytic and astrocytic cell tumors, since there was diffuse immunoreactivity for Olig2 and GFAP, in case 1 and case 2, respectively. Olig2, one of the first identified transcription factors that regulates oligodendroglial development, has an intranuclear localization and is useful for detecting normal and neoplastic oligodendroglial cells (20,21). MAC387 and lysozyme-positive cells in both cases were considered to be reactive macrophagic cells within the tumors, while the occasional GFAP-positive cells identified in case 1 were considered to be additional heterotopic cells entrapped within the tumor.

The clinical course of human PDLG is short with survival times from the first symptoms to death being less than 12 mo, in most cases due to the disease being misdiagnosed as meningitis or to the lack of appropriate treatment (1). The high mitotic rate and the widespread diffusion of the tumor at presentation may account for the poor prognosis (1,22) even if recent reports suggest that treatment combining radiation and chemotherapy can improve survival (5,14). In the cases herein, the imaging and histopathologic features of the tumor resembled the human counterpart, leading to a poor prognosis. The neurological condition at presentation was severe in both cases and owners elected euthanasia before we were able to perform other diagnostic procedures (such as biopsy or repetitive CSF taps) or plan other treatments such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Characteristic aspects of the disease are the difficulty in making a diagnosis because of its rarity and clinical resemblance to aseptic meningitis, and its extensive and aggressive nature, refractory to intensive radiotherapy and chemotherapy (1,15). The diagnosis of PDLG in humans is most often made at autopsy, mainly because of lack of specific clinical, radiologic, and laboratory diagnostic criteria, and the progressive natural history of the disease (1,15).

This case report documents the first 2 cases of PDLG in dogs. Even if additional cases and further study are warranted to have a more detailed clinical and pathological picture of PDLG, we suggest that it should be considered as a differential diagnosis in dogs with progressive signs of intracranial dysfunction and with MRI findings of diffuse leptomeningeal alterations with no parenchymal involvement. CVJ

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at the 24th ESVN Annual Symposium, Trier, Germany, September 2011.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Yomo S, Tada T, Hirayama S, et al. A case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:209–216. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukui MB, Meltzer CC, Kanal E, Smirniotopoulos G. MR Imaging of the meninges. Radiology. 1996;201:605–612. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riva M, Bacigaluppi S, Galli C, Citterio A, Collice M. Primary leptomeningeal gliomatosis: Case report and review of the literature. Neurol Sci. 2005;26:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debono B, Derrey S, Rabehenoina C, Proust F, Freger P, Laquerrière A. Primary diffuse multinodular leptomeningeal gliomatosis: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somja J, Boly M, Sadzot B, Moonen G, Deprez M. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis: An autopsy case and review of the literature. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2010;110:325–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandara MT, Rosi F, Lepri E, Angeli G. Cerebellar leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48:504–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2007.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mateo I, Lorenzo V, Munoz A, Molin J. Meningeal carcinomatosis in a dog: Magnetic resonance imaging features and pathological correlation. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2009.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roynard P, Behr S, Barone G, Llabres-Diaz F, Cherubini GB. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis in six dogs: MRI, CSF and histopatological findings, treatment and outcome. J Small Anim Pract. 2012;53:543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2012.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roussy G, Cornil L, Leroux R. Tumeur meningee a type glial. Revue Neurologique (Paris) 1923;30:294–298. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patnaik AK, Erlandson RA, Lieberman PH, Fenner WR, Prata RG. Choroid plexus carcinoma with meningeal carcinomatosis in a dog. Vet Pathol. 1980;17:381–385. doi: 10.1177/030098588001700312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipsitz D, Levitski RE, Chauvet AE. Magnetic resonance imaging of a choroid plexus carcinoma and meningeal carcinomatosis in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1999;40:246–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.1999.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietrich PY, Aapro MS, Rieder A, Pizzolato GR. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis (PDLG): A neoplastic cause of chronic meningitis. J Neurooncol. 1993;15:275–283. doi: 10.1007/BF01050075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonçalves AL, Masruha MR, Carrete H, Jr, Stavale JN, Da Silva NS, Pereira Vilanova LC. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis. Arquivos de Neuropsiquiatria. 2008;66:85–87. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2008000100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beauchesne P, Pialat J, Duthel R, et al. Aggressive treatment with complete remission in primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis. J Neurooncol. 1998;37:161–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1005888319228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilic M, Welsh CT, Rumboldt Z, Hoda RS. Disseminated primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis: A case report with liquid based and conventional smear cytology. Cytojournal. 2005;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louis DL, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper IS, Kernohan JW. Heterotopic nests in the subarachnoid space: Histologic characteristics, mode of origin and relation to meningeal gliomas. J Neuropath Exp Neurol. 1951;10:16–21. doi: 10.1097/00005072-195110010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korein J, Feigin I, Shapiro MF. Oligodendrogliomatosis with intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 1957;7:589–594. doi: 10.1212/wnl.7.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleihues P, Cavenee WK. World Health Organization classification of tumours Pathology and genetics of tumours of the nervous system. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoo H, Nobusawa S, Takebayashi H, et al. Anti-human Olig2 antibody as a useful immunohistochemical marker of normal oligodendrocytes and gliomas. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1717–1725. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63730-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galán A, Guil-Luna S, Millán Y, Martìn-Suárez EM, Pumarola M, de Las Mulas JM. Oligodendroglial gliomatosis cerebri in a poodle. Vet Comp Oncol. 2010;8:254–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2010.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rees JH, Balakas N, Agathonikou A, et al. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis simulating tubercolous meningitis. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:120–122. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]