Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge and vaccine acceptability in a convenience sample of immigrant Hispanic men, many of whom are parents of adolescents. Data on 189 male callers were collected from the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service Spanish-language call center. Most participants were willing to vaccinate their adolescent son (87.5 %) or daughter (78.8 %) against HPV. However, among this sample, awareness of HPV was low and knowledge of key risk factors varied. These findings can help guide the development of culturally informed educational efforts aimed at increasing informed decision-making about HPV vaccination among Hispanic fathers.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus (HPV), HPV vaccine acceptability, Hispanic men, HPV knowledge

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States, with more than 40 different types that can infect the genital area of both men and women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010; Weinstock et al., 2004). While HPV infection is most readily recognized as a causative factor in cervical cancer among women, men are also at risk for HPV-related morbidity and mortality (Bosch et al., 1996; Bosch et al., 2002). Among sexually active men aged 18–40 years, the prevalence rate of anogenital HPV is estimated to be as high as 72 % (Dunne et al., 2006). Oncogenic HPV types, mainly types 16 and 18, may be responsible for up to 93 % of anal cancers, 63 % of oropharyngeal cancers, and 36 % of penile cancers (Gillison et al., 2008; Guiliano et al., 2010). Non-oncogenic types, mainly types 6 and 11, are associated with genital warts (Gillison et al., 2008). Heterosexual men infected with HPV put their female partners at increased risk for cervical disease and genital warts (Bosch et al., 1996). In homosexual and bisexual men, the prevalence of anal HPV infection is about 60 %, and it is even higher among HIV-positive individuals, in whom it is estimated to be as high as 90 % (Chin-Hong et al., 2004; Palefsky et al., 1998). Racial and ethnic minorities account for a greater proportion of men diagnosed with HPV-related cancers (Benard et al., 2008; Watson et al., 2008). Additionally, Hispanic men may be disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and other STIs that put them at risk for HPV infection (CDC, 2008). A recent study reported that Hispanic ethnicity was independently associated with oncogenic and non-oncogenic HPV types (Nielson et al., 2009).

There are currently two prophylactic vaccines against HPV infection approved for use among females in the United States (CDC, 2010). Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of the quadrivalent vaccine for adolescent males and young men, ages 9–26, for use in the prevention of genital warts (CDC, 2010). For maximum public health benefit, HPV vaccination should occur in early adolescence prior to sexual initiation (Hildesheim & Herrero, 2007). Thus, it is important to examine HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability among parents, the primary decision makers for adolescents. Given that Hispanic adolescents are at particularly high risk for HPV infection after they become sexually active, studies that examine HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability among Hispanic parents are critical.

Studies examining HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability among Hispanic men are limited (Daley et al., 2011; Liddon et al., 2010). In general, study findings suggest that many men, regardless of race or ethnicity, are unaware of HPV and that their understanding and knowledge of HPV infection and its health consequences is low (Bair et al., 2008; Colón-López et al., 2010; Reiter et al., 2010b). In a recent study (Reiter et al., 2010b), nearly 40 % of heterosexual men were unaware of HPV. However, even among those who were aware of HPV, accurate knowledge of its transmission and its sequelae was low, with a mean number of correct responses of 3.5 out of 9.0.

Existing research on HPV vaccine acceptability has focused on females, so considerably less is known about HPV vaccine acceptability among males. A recent systematic review of HPV acceptability studies among males found that most studies use convenience samples, do not rely on nationally representative samples, and do not focus on vulnerable subpopulations at risk for HPV infection (Liddon et al., 2010). No study focuses specifically on Hispanic men. Overall, studies indicate that adult males are supportive of HPV vaccination for themselves, with acceptance rates ranging from33 %to 75 % (Ferris et al., 2008; Lenselink et al., 2008; Reiter et al., 2010b). Studies also indicate that acceptability is high among college students (74–78 %) but lower in community-based samples (33 %; Boehner et al., 2003; Jones & Cook, 2008). Among parents, studies examining HPV vaccine acceptability have been conducted among relatively homogenous groups, but acceptability has not been well characterized for Hispanic parents. To date, studies have found a range of acceptability rates, from 55 to 100 %, for parents willing to vaccinate their children against HPV (Brewer & Fazekas, 2007).

HPV vaccines hold significant potential to eliminate health disparities associated with HPV infection. However, the public health benefit of prophylactic vaccination can only be experienced if the vaccine is accepted by at-risk populations. Although research on HPV vaccine acceptability has increased in recent years, studies that include Latino/Hispanic populations are limited, with those that examine the perspective of Hispanic men being even more limited. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability in a convenience sample of immigrant Hispanic men. As parents of children at risk for HPV infection, their role is an important and understudied component of HPV vaccine uptake among adolescents. Results of this study can contribute to the development of effective, culturally informed educational messages about HPV and help identify opportunities to educate Hispanic fathers to make informed decisions about HPV vaccination for their children and even for themselves, if age-eligible.

Methods

Study Design and Procedure

The data for this cross-sectional study were drawn from a convenience sample of Spanish-speaking male callers from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Cancer Information Service (CIS). The former CIS Coastal Region operated a Spanish-language call center with trained information specialists providing cancer information to approximately 4,000 callers annually. As part of usual service, CIS information specialists document the primary reason(s) for each call and capture sociodemographic characteristics of callers. From July 2007 to March 2008, investigators from the University of Miami (UM) Miller School of Medicine, where the Spanish-language call center was then located, partnered with CIS staff to collect additional data on HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability. After usual service, CIS information specialists asked eligible callers to participate in a brief survey about HPV and cervical cancer. Callers were considered ineligible for participation if they resided outside the United States, were deemed emotionally distressed, or self-identified as a health professional and/or member of the media. Interested and eligible callers were consented to participate in this study using a two-step process approved by the UM Miller School of Medicine’s institutional review board. The interview took approximately 10–15 min to complete and was conducted completely in Spanish. When possible, survey items were derived from previously validated instruments and questionnaires (Dempsey et al., 2006; Marín et al., 1987; NCI, 2009).

Participants

Of 396 male callers to the Spanish-language call center, 224 (56.6 %) agreed to participate in the study. We included only those who identified as Hispanic and who were not born in the United States or Spain, leaving a final analytic sample of 189. Men born in the United States (n = 12) or Spain (n = 2) were excluded because of their small numbers, as well as because this study focused specifically on immigrant perspectives on HPV acceptance and vaccination.

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics

As part of standard protocol, CIS information specialists asked all participants (N = 189) for their age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education, income, and current healthcare coverage. Additionally, all participants reported their country of origin, length of time living in the United States, and primary language spoken overall and in various social contexts such as healthcare provider interactions. Questions for the language items were adopted from the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH), a well-known, validated instrument for measuring acculturation (Marín et al., 1987).

HPV Awareness and HPV Knowledge

All participants (N = 189) were then asked three items related specifically to awareness of the Pap test and HPV. Only those that answered “yes” to the question “Have you ever heard of HPV?” (n = 91) were then asked nine true/false questions regarding knowledge of individual risk factors for cervical cancer and HPV. The number of correct answers for each participant was summed and categorized into “low” (0–3), “medium” (4–6), and “high” (7–9) knowledge.

HPV Vaccine Acceptability

Prior to asking questions regarding participants’ willingness to vaccinate their sons and/or daughters against HPV, CIS information specialists delivered a brief educational intervention that included factual information about HPV and cervical cancer to all participants, whether or not they were aware of HPV. If the participant was the parent of an adolescent between the ages of 9–26 (n = 109), he was then asked to respond to one item measuring the outcome variable, acceptability: “How likely are you to vaccinate your adolescent daughter and/or son?” Participants answered “very likely,” “likely,” “unlikely,” “very unlikely,” or “don’t know.” If the participant was not the parent of an adolescent (n = 77), he was thanked for his participation, and the survey was concluded.

Attitudes About HPV Vaccination

Parents of adolescents (n = 109) were then asked questions regarding their attitudes and beliefs about HPV vaccination. These questions were based on psychological constructs from two validated models of health protective behavior: the Health Belief Model (HBM; Becker, 1974) and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA; Fishbein & Ajzen 1975). The normative belief constructs were derived from the TRA and were assessed with two items that measured how much participants were motivated to comply with the preference of their peers and physicians. The remaining constructs were derived from the HBM, and focused on (1) perceived susceptibility of disease; (2) perceived severity of disease; (3) perceived benefits of HPV vaccination; and (4) perceived barriers to HPV vaccination. Likert scales (ranging from 1 [strongly disagree] to 5 [strongly agree]) were used.

Analytic Plan

We first calculated univariate frequencies for sociodemographic variables for all participants (N = 189). For all participants, we calculated how many had heard of the Pap test, of HPV, and of the HPV vaccine. Only those who had heard of HPV (n = 91) were asked if they were aware of the HPV vaccine. The number of participants who correctly answered each question related to HPV knowledge was calculated. As described above, all callers were given a brief educational intervention on HPV, and then asked 10 questions assessing their attitudes about the HPV vaccine. Responses were tabulated and graphed, including a category for “don’t know.” We then calculated univariate frequencies for willingness to vaccinate their adolescent sons and/or daughters for those participants who were parents of an adolescent (n = 109). Finally, we constructed two multivariate logistic regression models to determine what factors were associated with participants’ willingness to vaccinate their sons and/or daughters with the HPV vaccine. The first model had willingness to vaccinate daughters as an outcome variable, and only fathers with daughters were included. The second model had willingness to vaccinate sons as an outcome variable, and only fathers with sons were included. A father was recorded as “willing” to vaccinate if he responded “very likely” or “likely” to vaccinate. Explanatory variables included prior HPV vaccine awareness, age, education, income, health insurance, years in the United States, and Mexican origin. Because there is such limited information on which factors affect male attitudes towards HPV vaccination, our analyses were exploratory rather than hypothesis-driven.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of all study participants (N = 189) are shown in Table 1. Approximately 66 % of participants were under the age of 50. Approximately one-third (30 %) had less than a high school education. Over half (52 %) reported a household income below $19,000, and 57.2 % reported not having health insurance. Overall, 58.6 % of participants were the parent of an adolescent child between the ages of 9 and 26 (the CDC-recommended age range for HPV vaccination). Regarding self-reported health, 50 % of participants reported having fair or poor health. The majority of participants (76.2 %) were not current smokers. Approximately half (49.2 %) reported that Mexico was their country of origin. The countries of origin of the remaining participants were combined into regions and reported as follows: South America (23.8 %), Central America (18.5 %), and the Caribbean, including Cuba and Puerto Rico. Nearly 70 % of participants reported living in the United States for 10 years or more. In terms of language spoken, most participants (86.2 %) reported that they usually spoke only or mostly Spanish. Most participants (60.4 %) also reported that they usually spoke only or mostly Spanish to their physician or healthcare provider, whereas close to 40 % reported speaking only or mostly English.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of all participants (N = 189)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years; N = 189) | ||

| 18–35 | 56 | 29.6 |

| 36–50 | 69 | 36.5 |

| 51+ | 64 | 33.9 |

| Education (n = 186) | ||

| Less than high school | 56 | 30.1 |

| High school graduate | 63 | 33.9 |

| Some college | 28 | 15.0 |

| College graduate or more | 39 | 21.0 |

| Household income (n = 177) | ||

| $19,000 or less | 92 | 52.0 |

| $20,000–$39,000 | 59 | 33.3 |

| $40,000 or more | 26 | 14.7 |

| Health insurance (n = 187) | ||

| No | 107 | 57.2 |

| Yes | 80 | 42.8 |

| Has a child between ages 9 and 26 (n = 186) | ||

| No | 77 | 41.4 |

| Yes | 109 | 58.6 |

| Self-rated health (n = 174) | ||

| Excellent | 20 | 11.5 |

| Good | 67 | 38.5 |

| Fair | 71 | 40.8 |

| Poor | 16 | 9.2 |

| Smoked in last 30 days (N = 189) | ||

| No | 45 | 23.8 |

| Yes | 144 | 76.2 |

| In United States 10 years or more (N = 189) | ||

| No | 57 | 30.2 |

| Yes | 132 | 69.8 |

| Language mainly spoken (N = 189) | ||

| All Spanish/mostly Spanish | 163 | 86.2 |

| Equal/mostly English/all English | 26 | 13.8 |

| Language spoken with doctor or healthcare provider (n = 187) | ||

| All Spanish/mostly Spanish | 113 | 60.4 |

| Equal/mostly English/all English | 74 | 39.6 |

| Region of origin (N = 189) | ||

| The Caribbean | 16 | 8.5 |

| Central America | 35 | 18.5 |

| Mexico | 93 | 49.2 |

| South America | 45 | 23.8 |

Number of responses in each category varied due to non-response

The percentages of those who had heard of the Pap test, HPV, and the HPV vaccine among all participants (N = 189) are presented in Table 2. A majority of participants (87.3 %) reported having heard of the Pap test. However, less than half of participants (48.2 %) reported having heard of HPV. Among these HPV-aware men (n = 91), awareness of the HPV vaccine known as Gardasil was 52.7 %. As mentioned previously, HPV knowledge was assessed only in HPV-aware participants. Table 3 presents the results of the nine true/false questions regarding knowledge of individual risk factors for cervical cancer and HPV and a summary score of items answered correctly. Overall, accurate knowledge of risk factors for HPV and cervical cancer varied. Most participants knew that multiple sexual partners increased the risk of cervical cancer and HPV infection (84.4 %) and that condoms can prevent the spread of HPV (76.4 %). Also, most knew that HPV is sexually transmitted (68.1 %) and that people infected with HPV might not have symptoms (65.2 %). However, fewer participants knew that HPV causes cervical cancer (56 %), that HPV can cause genital warts (32.6 %), and that HPV is common (39.6 %). Less than one-third (29.2 %) had high HPV knowledge, i.e., answered 7–9 items correctly.

Table 2.

Awareness of Pap test, HPV, and HPV vaccine

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Pap test among all participants (N = 189) | ||

| No | 24 | 12.7 |

| Yes | 165 | 87.3 |

| Awareness of HPV among all participants (N = 189) | ||

| No | 98 | 51.9 |

| Yes | 91 | 48.2 |

| Awareness of HPV vaccine among participants who were aware of HPV (N = 91) | ||

| No | 43 | 47.3 |

| Yes | 48 | 52.7 |

Table 3.

HPV knowledge among participants who were aware of HPV (n = 91)

| HPV-related question | % correct |

|---|---|

| HPV causes cervical cancer | 56.0 |

| HPV is a sexually transmitted disease | 68.1 |

| HPV infection is rare | 39.6 |

| HPV can cause abnormal Pap smears | 44.4 |

| Cigarette smoking increases your chances of getting cervical cancer | 63.3 |

| Having many sexual partners increases your risk of getting HPV and cervical cancer | 84.4 |

| Genital warts are caused by HPV | 32.6 |

| Condoms can prevent the spread of HPV from person to person | 76.4 |

| People infected with HPV might not have symptoms | 65.2 |

| Categories of knowledge | |

| Low (0–3 correct) | 21.4 |

| Medium (4–6 correct) | 49.4 |

| High (7–9 correct) | 29.2 |

Number of responses for each question varied between 90 and 91 due to non-response

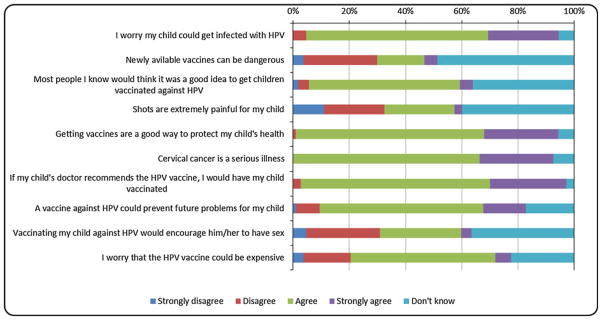

The Fig. 1 shows the results of attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination among participants who were parents of adolescents (n = 109). Overall, participants’ attitudes about vaccines as a way to protect their child’s health were overwhelmingly positive, as measured by those responding “agree” or “strongly agree” (93.4 %). The vast majority of participants (92.5 %) agreed with the statement that cervical cancer is a serious illness. Most perceived their children to be at risk for HPV infection (89.8 %). Most participants also perceived that the HPV vaccine could prevent future health problems (73.3 %), but a few were unsure (17.1 %). Attitudes regarding reasons not to vaccinate (i.e., cost, danger, pain, encouragement to have sex) varied considerably. Some participants thought that vaccines could be painful (27.8 %) and that new vaccines could be dangerous (21.5 %). However, many participants were unsure if vaccines are painful (39.8 %) or dangerous (48.6 %), and an additional 30 % disagreed with both of those concerns. These findings indicate that there was considerable uncertainty among participants about the safety of vaccines and their own fears regarding discomfort. Additionally, participants were uncertain if vaccination against HPV would encourage sex: 30.8 % agreed, while 32.7 % disagreed and 36.5 % were unsure. With respect to cost, more than two-thirds of participants (67.0 %) thought that the HPV vaccine is likely to be expensive. The majority of participants (94.4 %) reported that if their child’s physician recommended the HPV vaccine, they would have their child vaccinated. Many participants (58.3 %) also reported that people they knew would approve of their receiving the vaccine. However, over just over one-third of participants (36.1 %) were unsure of how their peers would feel about the idea of HPV vaccination.

Fig. 1.

Attitudes about HPV vaccine and vaccines in general among participants who were parents of adolescents (n = 109) (Number of responses varied between 105 and 108 due to non-response)

As shown in Table 4, study participants were overwhelmingly willing to vaccinate their adolescent son (87.5 %) or daughter (78.8 %). Although not statistically significant, participants were more uncertain regarding their willingness to vaccinate their daughters (16.5 %) than their sons (5.6 %). Table 5 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis. The explanatory variables included prior HPV awareness, sociodemographic variables, whether participants had been in the United States 10 years or more, and whether participants were of Mexican origin. No independent variables were significantly associated with willingness to vaccinate. Importantly, many variables were excluded from the multivariate logistic regression models because of multicollinearity; these variables included general health status, language spoken, smoking status, parental status, HPV knowledge, and attitudes towards HPV vaccination. Additionally, some variables were excluded because of missing values. It is likely that this issue of multicollinearity is due to the fact that participants were overwhelmingly willing to vaccinate their children, with only 4.7 % stating that they would not be willing to vaccinate their daughter and 6.9 % stating that they would not be willing to vaccinate their son.

Table 4.

Willingness to vaccinate daughters and/or sons among participants who were parents of adolescents

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| How likely are you to vaccinate your adolescent daughter? (n = 83)a | ||

| Very likely/likely | 66 | 79.5 |

| Unlikely/very unlikely | 4 | 4.8 |

| Don’t know | 13 | 15.7 |

| How likely are you to vaccinate your adolescent son? (n = 72)a | ||

| Very likely/likely | 63 | 87.5 |

| Unlikely/very unlikely | 5 | 6.9 |

| Don’t know | 4 | 5.6 |

Significant differences in percentages in categories of likelihoods of vaccinating sons and/or daughters, χ2 = 6.248, df = 2, p = .04

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression showing association between variables and willingness to vaccinate sons and/or daughters for HPV

| Vaccinate daughters (odds ratio [confidence interval]) | Vaccinate sons (odds ratio [confidence interval]) | |

|---|---|---|

| Aware of HPV | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 3.17 [0.74, 13.63] | 1.95 [0.33, 11.54] |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–26 | Ref | Ref |

| 27–44 | 1.61 [0.20, 13.0] | 1.02 [0.08, 12.55] |

| 45+ | 2.41 [0.29, 20.15] | 1.16 [0.08, 16.08] |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school or high school | Ref | Ref |

| Some college | 0.49 [0.07, 3.47] | 0.15 [0.02, 1.19] |

| College graduate or more | 1.63 [0.28, 9.58] | 1.00 [0.11, 9.65] |

| Household income | ||

| $19,000 or less | Ref | Ref |

| $20,000–$39,000 | 0.93 [0.25, 3.43] | 0.93 [0.14, 6.11] |

| $40,000 or more | 3.83 [0.35, 41.67] | 0.54 [0.06, 4.63] |

| Health insurance | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 0.27 [0.07, 1.01] | 0.56 [0.10, 3.28] |

| In United States 10 years or more | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 2.26 [0.55, 9.34] | 0.36 [0.03, 4.63] |

| Mexican origin | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.97 [0.46, 8.45] | 2.02 [0.29, 14.08] |

Statistical significance was set at p<.05.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess awareness and knowledge of HPV and its related risk factors, and to examine attitudes regarding HPV vaccination in a convenience sample of immigrant Hispanic men. Additionally, we were interested in looking at vaccine acceptability among Hispanic fathers, who share parental consent for a population at high risk for HPV infection and in whom little research has been conducted. Our results indicate that HPV vaccine acceptance was very high among this sample of Hispanic fathers. The acceptance rate was high even though this sample was overwhelmingly foreign-born and reported low levels of education, income, and health insurance coverage. Additionally, attitudes about vaccines generally and HPV vaccine specifically were positive. However, overall awareness of HPV was not high following the post-licensure media and direct-to-consumer advertising of the HPV vaccine. Furthermore, accurate knowledge of risk factors for HPV and cervical cancer varied in this sample.

Overall, study participants were overwhelmingly willing to vaccinate their adolescent sons (79.5 %) or daughters (87.5 %). These findings are consistent with those of other studies conducted in the United States indicating that most adult males and parents of boys support vaccination (Liddon et al., 2010). Our rates are slightly higher than those reported for male college students and their willingness to self-vaccinate (74–78 %) and significantly higher than those reported for community samples of non-Hispanic men (33–48 %) (Ferris et al., 2008; Jones & Cook, 2008; Reiter et al. 2010a). Our findings are more consistent with results from the Natural History Study of HPV Infection in Men (HIM study), which similarly reported higher vaccine intentions among Hispanic men (95 %) than among non-Hispanic White men (74 %) and non-Hispanic Black men (81 %) (Daley et al., 2011). While there is little to no research on Hispanic fathers regarding HPV vaccine acceptability for their children, a study comparing HPV vaccine acceptability of Latino/Hispanic mothers to that of non-Latino mothers found that Latino mothers were significantly more willing than non-Latino mothers to vaccinate their sons (Watts et al., 2009).

The vast majority of study participants (93.5 %) had positive attitudes about vaccines as a way to protect their child’s health and most (73.3 %) believed that the HPV vaccine could prevent future health problems in their child. It is likely that this foreign-born sample has had previous experience with and recognizes the importance of vaccination. For example, Mexico has had overwhelming success in their ability to link immunization programs to all of the health sectors in the country, and has implemented successful national campaigns focused on immunization for children (Santos et al., 2004). Because approximately half of our study sample was from Mexico, it is possible that this positive perception of vaccination continues to play a favorable role in influencing their attitudes towards acceptability of a new vaccine in this country. A recent study found that Mexican immigrant parents were accepting of a vaccine against STIs and that they strongly endorsed several different vaccine-related scenarios assessing willingness (Bair et al., 2008).

There is consistent evidence that HPV awareness and knowledge is not distributed evenly among racial and ethnic groups and that lack of HPV awareness and knowledge persists even after the vaccine is available (Cates, et al., 2009; Daley et al., 2011). With HPV awareness at 48 %, this study seems to substantiate these existing disparities. This may speak to the fact that a significant portion of health education around HPV and the HPV vaccine has been aimed exclusively at women. It may also speak to the complexity of the HPV virus, its ability to clear in some populations while persisting in others, and its well-publicized link to cervical cancer rather than to other male-specific cancers. Lastly, it may speak to the low health literacy among racial and ethnic minorities. A study conducted among ethnically and racially diverse patients found that close to half had difficulty understanding HPV information (Schillinger et al., 2002).

It is also clear from this study that accurate, detailed knowledge about HPV and its association with genital warts, cancer, and sexual behavior is lacking. Even with almost half of the study population aware of HPV, there were knowledge gaps relating to transmission, risky behavior, and its ubiquity as the most common STI in the United States. This is particularly important in a post-vaccine era when considerable media coverage and direct-to-consumer advertising has resulted in increased awareness, but not necessarily in increased knowledge. Increasing the depth of knowledge among men who may have heard of HPV is important for increasing informed decision-making about HPV vaccination. Future research should examine where Hispanic men would want to acquire information about HPV both for themselves and for their adolescent children. It is important to investigate what sources would be considered trustworthy for additional information and what avenues would support culturally appropriate health communication interventions. Recent studies on other STIs, such as HIV and syphilis, suggest that culturally tailored interventions are more effective than generic messages (Colón-López et al., 2010; DiClemente et al., 2004).

The finding of such high rates of HPV vaccine acceptability in this Spanish-speaking, immigrant population is interesting and points to several possible explanations around cultural influences on immunization practices. For example, newly arrived immigrants may be less likely to view mainstream English-language media and thus are less likely to be exposed to anti-vaccine messages discussing the negative side effects of vaccination. The probability of being exposed to such messages likely increases with acculturation and with time spent living in the United States. In this study, close to one-third of participants have been in this country for less than 10 years, and over 85 % spoke mostly or only Spanish. Another potential explanation involves the cultural concept of family, or familia, that is integral for Hispanics (Negy & Woods, 1992; Sabogal et al., 1987). While not measured directly in this study, strong feelings of family and parental responsibility have been shown to lessen as individuals migrate to this country away from family ties and obligations and into the more individualistic US culture. There is evidence that a sense of parental responsibility is stronger in less acculturated individuals and this may impact vaccination rates (Sabogal et al., 1987). This may partly explain the very high acceptance rates in this study when men were asked about vaccinating their sons and/or daughters. Given that this population views vaccines in such a positive manner, feelings that support vaccination as an important component of taking care of ones’ family would be consistent with positive attitudes towards HPV vaccination.

Finally, the very high rate of acceptance may be attributed to the unique nature of CIS callers, all of whom were actively seeking cancer information at the time of survey administration. There is a body of research that states that those who have enhanced information access and information-seeking skills are in a more favorable position to obtain information and make informed medical decisions across the spectrum of health and illness (Viswanath & Finnegan, 1996). It can be argued that by virtue of their call to the CIS and their knowledge of a national resource for cancer information, this group of Hispanic men are more likely to be active information seekers and thus are different than typical monolingual Hispanics residing in the United States. Perhaps it is for this reason that willingness to vaccinate was exceptionally high.

This study also found that a notable number of participants were unsure of their beliefs or had not yet formed opinions about certain aspects of the HPV vaccine. This was particularly true when considering barriers to vaccination including side effects and cost, as well as when considering what their peers thought of getting vaccinated. Newly introduced vaccines may therefore require additional education or counseling on the part of healthcare providers in order to allay safety-related and other concerns. Previous research has indicated that physician recommendation is an important predictor of vaccination in this population (Ferris et al., 2009; Gerend & Barley, 2009; Liddon et al., 2010). In this study, almost 95 % of participants reported that they believed if their child’s physician recommended the HPV vaccine, they would have their child vaccinated. Clearly, healthcare providers can play a critical role in informing parents and providing important information to help manage the current uncertainty that this population may have relating to the perceived danger and side effects of HPV vaccination for their children.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting our results. Participants were recruited from callers who contacted the NCI’s CIS Spanish-language call center. Generalization from this population is thus limited given that those who contact the CIS can be classified as information seekers and may represent those with higher motivation and interest in cancer-related issues and perhaps a greater interest in preventive health behaviors such as HPV vaccination. Additionally, the design of the study did not allow us to collect data on actual behaviors relating to HPV vaccine uptake or other related health behaviors; therefore, the degree extent to which participants’ reported intention/willingness to vaccinate their children matched their actual past and future behaviors is not known. However, intention to vaccinate has been shown to be a good, but not a perfect, predictor of subsequent vaccination behavior (Armitage & Connor, 2001; Rosenthal et al., 2008). Furthermore, a significant body of research on models of health protective behavior like the TRA and the HBM indicate that measuring the intention to engage in a behavior like vaccination is a significant and reliable predictor of subsequent engagement of the behavior (Becker, 1974; Dempsey, et al., 2006; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

Finally, this study asked men to think about HPV vaccination in terms of vaccinating their adolescent daughter and/or son. The research was conducted at a time when recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) were only available for females. Thus, we did not explore male personal willingness to vaccinate. However, it is worth noting that close to 40 % of the study participants were age-eligible for the HPV vaccine. The high rate of acceptance suggests that men might be willing to accept HPV vaccination for themselves, thereby reducing their own risk of HPV infection or that of their female or same-sex partner. Examining additional factors that may also influence the beliefs and opinions of men about HPV vaccines is an area ripe for future research given the ACIP’s updated recommendations for male vaccination.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study provides important information about Hispanic men’s awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and the HPV vaccine. Additionally, given the focus on fathers and their shared role in decision-making for adolescents, these results provide critical insight that is not currently available in the literature and can help to guide culturally informed primary prevention efforts aimed at Hispanic fathers. These significant knowledge gaps are particularly critical to explore because men who were unsure or unaware of specific risk factors may gather incorrect information or experience additional barriers when exploring vaccination both for their children and themselves, and because intentions to vaccinate may not translate into vaccine uptake.

Contributor Information

Julie Kornfeld, Email: jkornfel@med.miami.edu, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Clinical Research Building, Room 910 (Locator code R669), 1120 NW 14th Street, Miami, FL 33136, USA.

Margaret M. Byrne, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Clinical Research Building, Room 910 (Locator code R669), 1120 NW 14th Street, Miami, FL 33136, USA

Robin Vanderpool, Department of Health Behavior, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY, USA.

Sarah Shin, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA.

Erin Kobetz, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Clinical Research Building, Room 910 (Locator code R669), 1120 NW 14th Street, Miami, FL 33136, USA.

References

- Armitage CH, Connor M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:417–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair RM, Mays RM, Sturm LA, Perkins SM, Juliar BE, Zimet GD. Acceptability to Latino parents of sexually transmitted infection vaccination. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH, editor. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–508. [Google Scholar]

- Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD, Roland KB, Lai SM, Cokkinides V, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(Suppl 10):2910–2918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehner CW, Howe SR, Bernstein DI, Rosenthal SL. Viral sexually transmitted disease vaccine acceptability among college students. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30:774–778. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000078823.05041.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch FX, Castellsagué X, Muñoz N, de Sanjosé S, Ghaffari AM, González LC, Shah KV. Male sexual behavior and human papillomavirus DNA: Key risk factors for cervical cancer in Spain. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88:1060–1067. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.15.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Muñoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2002;55:244–265. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Preventive Medicine. 2007;45:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates JR, Brewer NT, Fazekas KI, Mitchell CE, Smith JS. Racial differences in HPV knowledge, HPV vaccine acceptability, and related beliefs among rural, southern women. The Journal of Rural Health. 2009;25:93–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC HIV/AIDS Facts. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. HIV/AIDS among Hispanics/Latinos. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/hispanic.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, Buchbinder S, Cohen D, Colfax G, Palefsky JM. Age-specific prevalence of anal human papillomavirus infection in HIV-negative sexually active men who have sex with men: The EXPLORE Study. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;190:2070–2076. doi: 10.1086/425906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón-López V, Ortiz AP, Palefsky J. Burden of human papillomavirus infection and related comorbidities in men: Implications for research, disease prevention and health promotion among Hispanic men. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal. 2010;29:232–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley EM, Marhefka S, Buhi E, Hernandez ND, Chandler R, Vamos C, Giuliano AR. Ethnic and racial differences in HPV knowledge and vaccine intentions among men receiving HPV test results. Vaccine. 2011;29:4013–4018. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey AF, Zimet GD, Davis RL, Koutsky L. Factors that are associated with parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines: A randomized intervention study of written information and HPV. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1486–1493. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, 3rd, Robillard A. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized control trial. The Journal of the American Medicine Association. 2004;292:171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, Markowitz LE, Giuliano AR. Prevalence of HPV Infection among men: A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;194:1044–1057. doi: 10.1086/507432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, Patel P, Jackson L, Price GA, et al. Men’s attitudes toward receiving the human papillomavirus vaccine. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2008;12:276–281. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318167913e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, Patel P, Price GA, Jackson L, et al. Variables associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptance by men. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2009;22:34–42. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gerend MA, Barley J. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among young adult men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36:58–62. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818606fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowry DR. HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. Cancer. 2008;113(Suppl 10):3036–3046. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Anic G, Nyitray AG. Epidemiology and pathology of HPV disease in males. Gynecologic Oncology. 2010;117(Suppl 2):S15–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildesheim A, Herrero R. Human papillomavirus vaccine should be given before sexual debut for maximum benefit. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196:1431–1432. doi: 10.1086/522869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Cook R. Intent to receive an HPV vaccine among university men and women and implications for vaccine administration. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57:23–32. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.1.23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenselink CH, Schmeink CE, Melchers WJ, Massuger LF, Hendriks JC, van Hamont D, et al. Young adults and acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Public Health. 2008;122:1295–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddon N, Hood J, Winn BA, Markowitz LE. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine for males: A review of the literature. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Sabogal F, Marín BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 2007 final report. 2009 Retrieved from http://hints.cancer.gov/docs/HINTS2007FinalReport.pdf.

- Negy C, Woods DJ. A note on the relationship between acculturation and socioeconomic status. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1992;14:248–251. [Google Scholar]

- Nielson CM, Harris RB, Flores R, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss MR, Dunne EF, Giuliano AR. Multiple-type human papillomavirus infection in male anogenital sites: Prevalence and associated factors. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18:1077–1083. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Jay N. Prevalence and risk factors for human papillomavirus infection of the anal canal in human immunodeficiency (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative homosexual men. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;177:361–367. doi: 10.1086/514194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter PL, Brewer NT, McRee AL, Gilbert P, Smith JS. Acceptability of HPV vaccine among a national sample of gay and bisexual men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010a;37:197–203. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bf542c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Smith JS. Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among a national sample of heterosexual men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2010b;86:241–246. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.039065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal SL, Rupp R, Zimet GD, Meza HM, Loza ML, Short MB, et al. Uptake of HPV vaccine: Demographics, sexual history and values, parenting style, and vaccine attitudes. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Santos JL, Nakamura MA, Godoy MV, Kuri P, Lucas CA, Conyer RT. Measles in Mexico, 1941–2001: Interruption of endemic transmission and lessons learned. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;189(Suppl 1):S243–S250. doi: 10.1086/378520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, Bindman AB. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K, Finnegan JR., Jr . The knowledge gap hypothesis: Twenty-five years later. In: Burleson B, editor. Communication Yearbook. Vol. 19. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 187–227. [Google Scholar]

- Watson M, Saraiya M, Ahmed F, Cardinez CJ, Reichman ME, Weir HK, et al. Using population-based cancer registry data to assess the burden of human papillomavirus-associated cancers in the United States: Overview of methods. Cancer. 2008;113(Suppl 10):2841–2854. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts LA, Joseph N, Wallace M, Rauh-Hain JA, Muzikansky A, Growdon WB, et al. HPV vaccine: A comparison of attitudes and behavioral perspectives between Latino and non-Latino women. Gynecologic Oncology. 2009;112:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]