Abstract

Background

The Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI) aims to translate discovery into clinical practice. The Partnership of Academicians and Communities for Translation (PACT) represents a robust campus–community partnership.

Methods

The CCTSI collected data on all PACT activities including meeting notes, staff activity logs, stakeholder surveys and interviews, and several key component in‐depth evaluations. Data analysis by Evaluation and Community Engagement Core and PACT Council members identified critical shifts that changed the trajectory of community engagement efforts.

Results

Ten “critical shifts” in six broad rubrics created change in the PACT. Critical shifts were decision points in the development of the PACT that represented quantitative and qualitative changes in the work and trajectory. Critical shifts occurred in PACT management and leadership, financial control and resource allocation, and membership and voice.

Discussion

The development of a campus–community partnership is not a smooth linear path. Incremental changes lead to major decision points that represent an opportunity for critical shifts in developmental trajectory. We provide an enlightening, yet cautionary, tale to others considering a campus–community partnership so they may prepare for crucial decisions and critical shifts. The PACT serves as a genuine foundational platform for dynamic research efforts aimed at eliminating health disparities.

Keywords: community engagement, community‐based participatory research, translational research, clinical and translational science award

Background

The University of Colorado delayed its application for a Clinical and Translational Science Award1 (CTSA) to permit a planning year during which a number of options were developed and assessed to reorganize and improve the research enterprise. During this planning year, an additional research infrastructure was envisioned to enable a partnership among university investigators and communities. The ultimate goal of such a partnership became the reduction of health disparities in the Rocky Mountain Region through targeted investments in community translational research, followed by wider dissemination of successful practices. It was a transformative vision, building from existing relationships and programs, guided by the principles of community‐based participatory research.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Iterative conversations among investigators, community leaders, and the organizers of the CTSA proposal yielded three initial aims for a newly imagined Partnership of Academicians and Communities for Translation (PACT). The first aim was to transform rather haphazard and intermittent projects and relationships into a sustained, trustworthy enterprise for culturally proficient, community‐based translational research that matters to Rocky Mountain communities. The other initial aims focused on capacity building through practical and ongoing training for investigators and community members and on targeted community translation research initiatives. A respected health services researcher took on the initial role of Director of Community Engagement, willing communities and scientists were recruited to form an initial set of partners, and a small scientific staff was selected to support the work. A council comprised of 16 individuals, half representing communities and half academics was appointed by the Director to oversee development of the newly proposed community engagement pillar of the University's anticipated Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CCTSI).

The announcement of funding for the CCTSI engendered great excitement, enthusiasm, and some appropriate apprehension about the work to be done. A journey commenced, and 5 years later, a great deal has happened, some of it as planned, and much of it unanticipated. The purpose of this manuscript is to report the results of careful reflection and analysis by the participants in what may be best described as a creative collaborative journey over half a decade. We identified particular events, decisions, and adjustments that retrospectively can be seen as “critical shifts” that resulted in what the PACT has become today. Our intention is to reveal what it took in a particular setting to establish a successful, still evolving partnership that has emerged as a valued research infrastructure that might be missing, but needed in other settings.

Methods

The CCTSI Evaluation Core collected data on all PACT‐related activities including meeting notes, staff activity logs, key stakeholder surveys and interviews, and several key component in‐depth evaluations. These data were analyzed regularly by the Evaluation Core staff and shared with Community Engagement Core staff and PACT Council members. The CE research team reviewed these data and identified major themes and important milestones.

Members of the PACT Council Executive Committee worked with the CCTSI Community Engagement Staff and the Evaluation Core to analyze and interpret the data and produce this manuscript. The PACT Council Executive Committee is currently composed of two academic members and three community members.

Results

The Partnership of Academicians and Communities for Translation has undergone rapid development in the 5 years since inception. Development of the PACT was punctuated by important decisions that rapidly changed the trajectory of the PACT progress. We refer to critical shifts in the development of the PACT to describe these changes, the steps leading up to the decisions, and the sudden changes resulting from the decisions. The critical shifts were sometimes the result of small incremental changes, which lead to an important choice by the PACT Council or CCTSI Leadership. These decisions then lead to sudden change that had profound impact on the ongoing work of the Community Engagement Core and the PACT Council. Ten “critical shifts” were identified in six broad rubrics that marked the growth and transition of the PACT into its present form. Representative quotes from PACT Council members and Community Liaisons are included to illustrate these critical shifts.

(1) Loose Affiliation to Coalition to Council

The first few meetings of the PACT Council were dominated with conversation about the purpose of the Council within the context of the greater CCTSI grant and program. As a new organization, members were unclear of the Council structure, accountability, organization, rules, and whether the Council really had any power. Members were skeptical of whether the Community Engagement Core of the CCTSI was really interested and able to produce a new kind of organization and truly transform the way translational research was done at the University of Colorado. Year one was spent working on group interaction and the dynamics of academic and community members sitting together to craft a new type of entity with new core values different from the individual members. CCTSI Leadership, including the Principal Investigator and other senior investigators, attended PACT Council meetings. Their participation provided a broader context for the Community Engagement Core within the CCTSI and they witnessed and contributed to the emergence and maturation of this new organization.

During the final month of year one, the PACT Council had a 2‐day off‐campus retreat. The PACT Council came away from the retreat with renewed energy to develop and codify formal structures within the CE Core and the PACT Council. Over the following 12 months, bylaws, committees, and a formal framework of management were set in place by the Council.

Critical Shift. On May 11, 2010 the PACT Council formally adopted Rules of Operation, which included a clear outline of the mission, values, ground rules and operating procedures. The PACT Council became a governing body with appropriate structure, documents, policies, and procedures. The Council embraced standard parliamentary procedure and formal rules of order for regular PACT Council meetings, committee meetings, and communication between meetings. The Community Engagement Core Director became the primary person responsible for putting into action the decisions of the PACT Council. A formal committee structure was put into place with each committee co‐chaired by a staff member and a PACT Council member.

Critical Shift. The PACT Council elected an Executive Committee to meet monthly to address time‐sensitive issues (e.g., funding opportunities), serve as the nominating committee, and prepare the PACT Council agenda. The PACT Executive Committee consists of the Chair of the Council, four at‐large members and is staffed by the Community Engagement Core Director and Deputy Director. The Executive Committee currently includes two academic members and three community members.

“The expanded role of the Executive Committee has greatly contributed to our agility. This small sub‐group is highly respected and trusted.”

Critical Shift. The CCTSI Principle Investigator signed off on the formal Rules of Operation, effectively ceding some power and control to the PACT Council. This agreement by the CCTSI Leadership provided a profound endorsement of the PACT Council as a decision making body that had the authority to operate and manage resources independently. The PACT Council community members were assured that their place at the table was genuine and valued, not cursory or incidental.

(2) Membership in the PACT Council

Original members of the PACT Council were identified during the preparation of the CTSA grant application. Members were chosen based on their history of community engagement and collaboration with members of the staff. Half of the original members were from the University of Colorado academic community and half were from community organizations. The original members had years of experience in their organizations and were willing to participate in a grant proposal with uncertain funding. While committed to community engaged translational research, academic members were many of the usual suspects involved in translational, practice‐based, and health services research. Community members included organizations that had current strong partnerships with the University and also included several “affiliate” clinical institutions including National Jewish Health, Denver Health, and Kaiser Permanente of Colorado.

During the second year of the grant, a PACT Council community member passed away unexpectedly leaving an empty chair. The Council was working to develop a nomination process for identifying new PACT Council members. The decision was made to replace a community member with another community member to ensure that the Council remained half community and half academic. One additional community member was added in year two following the resignation of another community member in year one.

“We have come a long way since our first several meetings. We have developed a more collaborative approach toward discussions and projects.”

Critical Shift. During year three the Council made two major decisions related to PACT Council Membership. First came the decision to reclassify affiliate organizations, which had previously been considered community members of the PACT Council, as academic members. This essentially increased the community voice on the Council by three members to ensure a 50:50 distribution between academic and community voice.

The second decision was to more actively recruit new members for the PACT Council. Rather than simply replace a community member representing a specific race/ethnicity/or current PACT organization, nominations were opened up widely to the greater Colorado community. PACT Council members were tasked with identifying and nominating new members from a host of under‐represented populations and communities.

The PACT Council now has an active nomination process with the PACT Executive Committee serving as the Nominating Committee. One major role for the PACT Council is to regenerate itself through identifying, nominating, and recruiting appropriate members from the community and University. Rather than being hand selected by the Community Engagement Core Director or CCTSI, the PACT Council itself has chosen who needs to be at the table. With each new member, the PACT Council and Executive Committee have had an in‐depth conversation about current Council membership, missing voices, and the wide variety of Colorado communities interested in participation. Of the original 18 members, five have left the Council for a variety of reasons (death, work changes, etc.). The most recent vacancy resulted from the resignation of an academic member. To maintain the Council's commitment to a balanced membership with equal representation of community and academic participants, the Nominating Committee requested nominations for a community member to fill the vacancy. The Committee received and vetted seven nominations, presenting a slate of three nominees to the full PACT Council for final selection.

Critical Shift. Along with the changes in membership in the PACT Council, at the annual PACT Council Retreat the Council explicitly called out the difference between the PACT, the PACT Council, and each member's home institution. The Partnership of Academicians and Communities for Translation encompasses dozens of individuals and organizations committed to improving the health of all Coloradans and eliminate health disparities by translating the best healthcare into locally relevant and accessible healthcare. The PACT includes academic institutions, community organizations, individual academic and community members, funding agencies, health departments, and nongovernmental community‐based health organizations. Sometimes, the PACT Council makes decisions based on the best interests of the Council. However, at the annual retreat in year three, the PACT Council explicitly directed itself, the Director, and the staff to more actively work with all the partners in the PACT. To this end, the Community Engagement staff have developed and/or strengthened relationships with many organizations, such as the Colorado Area Health Education Centers, the Colorado Health Institute, local public health agencies and organizations serving the neighborhoods surrounding the Anschutz Medical Campus, such as the Aurora Fire Department.

(3) Role Definition

PACT Council members joined in an effort to improve the health of people in their communities. The task of translational research was new to most members. Hence, their role on the PACT Council was difficult to define. Members saw their role as providing community voice, input into research priorities, and as a link to their specific community. In the beginning it was unclear the level of power the PACT Council would wield in terms of resource allocation, program direction, and personnel oversight.

After the loss of the initial Community Engagement Core Director due to health issues, the PACT Council was tasked with identifying a new Director. While the final choice of Director required CCTSI and NIH Approval, the PACT Council was fully engaged in the process, reviewing applications, participating in interviews, and recommending a final candidate. This exercise in leadership provided the basis for the PACT Council to become a functional, decision making Council with authority.

Critical Shift. The Council voted unanimously to reallocate PACT Council reimbursement from a percentage of salary to a fixed amount for each PACT Council member. Academic Council members realized a significant decrease in their financial support and the community Council members saw a significant increase in their financial support as a result of this change. While incomes vary by a factor of three in their home institutions, in the PACT Council, every member's voice has equal value.

This dramatic shift in the budget of the CCTSI CE Core was the direct result of a powerful and equal voice for community members in the PACT Council. The PACT Council claimed its leadership and oversight role. Since then the PACT Council has made additional resource allocation decisions within the Pilot Grant program, the Community Liaison Program, and the staff.

We are now… “people with many potential conflicts of interest willing to prioritize the PACT.”

“Council members have a sense of identity separate from their parent organization; [they] check their parent organization at the door.”

Critical Shift. The PACT Council expressed a desire to become a research infrastructure that would exist for the long haul. Rather than a CTSA grant‐specific activity, the PACT Council began viewing itself through the lens of a long‐term collaborative effort with a 20+‐year lifespan. Unlike any other entity, the PACT provided a place for community members and academic researchers to join together in a robust discussion about local needs, local data, and local and regional solutions. Interestingly, the PACT Council members often declared dualities of interest. They wanted group transparency about agency and organizational affiliation. The PACT was not a source of revenue for the individual or their institutions; it was a new type of organization that could improve the health of all communities. By linking the best science with the best community knowledge, the PACT might produce something better than either could alone.

(4) Openness of PACT Council Meetings

From the beginning, PACT Council meetings were open to any and all who wished to attend. The goal of the first year was to have the PACT Council become a viable, functioning leadership group with its own identity. While the PACT Council was open to visitors, meeting times and dates were primarily distributed to PACT Council members and CE staff. PACT Council members were encouraged to invite others based on their community wishes. As the Council structure became more formal and secure it became clear that the PACT could benefit from additional voices, specifically from the newly engaged Community Liaisons. Initially, Community Liaisons could be invited to PACT Council meetings by the PACT Council member from their community. As the various roles of PACT Council members, Liaisons, and Scientific Staff became clearer, attendance at PACT Council Meetings was opened widely and all those with any involvement in the Community Engagement Core were welcome and directly invited. Specifically, as the tasks of the Community Liaisons changed from only working with their assigned PACT Council member to more general community engagement tasks, the Liaisons became an integral part of PACT Council meetings. Space was chosen to accommodate the larger attendance so that all could sit “at the table.”

“We feel welcomed now and are expected to contribute our community expertise to PACT council discussions. We are a strong group and now we have a stronger voice.”

Critical Shift. The move to explicitly and intentionally open the PACT Council meetings had a profound impact on the Community Liaisons and their broader community organizations. Essentially, this decision doubled the number of community members attending the PACT Council meetings and increased the presence of the community at the PACT and within the CCTSI. The PACT Council became a place to actively voice concerns and share excitement between academic members and community members. All attendees were given equal voice and the conversations became much more meaningful and grounded in the community perspective.

(5) Self‐Reflective Evaluation

In the early days of the PACT Council, members were frequently unclear of their tasks and purpose. The CCTSI Evaluation team worked closely with the CE staff to evaluate partnership development, membership expectations, Liaison work and satisfaction, and pilot grant outcomes. The evaluation team reported regularly to the PACT Council on the work and outcomes of the various components of the CE Core. Early on, the PACT Council struggled with how to interpret or act upon this evaluation data. How did each program fit together with the others? How could these data impact the next decision? Over time, the reflective evaluation led by the evaluation team produced a Council eager for data to inform current work and strategic planning.

Critical Shift. The evaluation of the pilot grant program was presented to the PACT Council, which led to a robust conversation about how to best apply pilot grant resources to translate evidence in to practice. The conversation was energetic and the excitement about opportunity was palpable. The self‐reflective nature of the evaluation provided a new capacity for council decision making. Whether about the pilot grant program, or any of the other PACT programs, the PACT Council is now equipped with the capacity to use data, reflect openly and honestly, and make decisions based on the best interests of the Council as a whole.

(6) Organization Change

During year two, the Community Engagement Core Director suffered a serious medical condition and stepped down from leadership in the University and PACT Council. The PACT Council Chair provided leadership and a formal search was conducted for a new Director. The PACT Council also decided to develop a new position of Deputy Director to manage day‐to‐day operations in lieu of the numerous part‐time staff. After a formal search, the PACT Council unanimously chose a new Director.

Critical Shift. This substantial change in PACT Council and CCTSI Leadership was approved by the CCTSI Principle Investigator providing additional evidence that the PACT Council could independently choose its leadership, direction, and resource allocation. The CCTSI Principal Investigator's regular attendance at PACT Council meetings and strong working relationship with the PACT Council provided him with the knowledge and experience to trust the community–campus process for choosing leadership and direction. The PACT Council has power to make personnel and resource decisions within the context of healthy academic–community collaboration.

Pact today

These 10 critical shifts bring us to our current form and function. Today, the PACT includes more than 25 community organizations throughout Colorado and is open to all groups, communities, and institutions committed to improving the health of their community. Seven focus communities employ a Community Liaison who serves as the conduit, broker, and gatekeeper for academic–community research partnerships. A pilot grant program provides over $200,000 per year to campus–community partnerships working on innovative research that addresses health disparities identified by the community.7 A vibrant educational program provides training for researchers and community members. The PACT data program aims to provide locally relevant actionable data to communities.

(1) The Partnership of Academicians and Communities for Translation consists of dozens of organizations that have community ties and relationships with providers and researchers at the University. The PACT continues to grow as new relationships are forged and new collaborations are activated. The PACT represents our aspirational approach to a true, bidirectional partnership between community members and groups committed to improving the health of and healthcare in their community and the University of Colorado. The PACT is led by the PACT Council and Community Engagement Core staff.

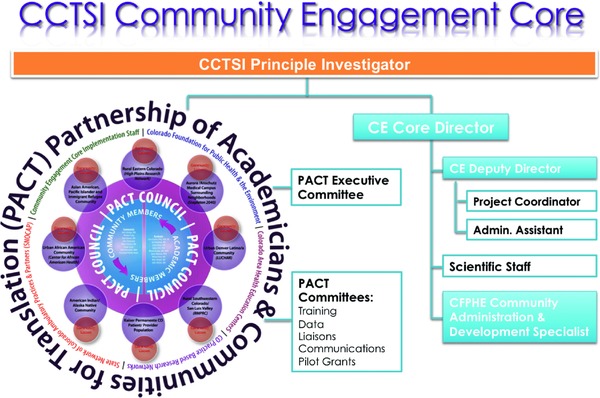

The PACT Council consists of 18 members with equal representation from the University and community and gives voice to more than 20 Colorado ethnic, geographic, and self‐identified communities facing a variety of health disparities. The PACT Council serves as the governing body providing leadership and authority for equitable resource allocation. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the Community Engagement core, the PACT and PACT Council. The PACT participates in the annual Engaging Communities in Education and Research conference, a combined conference for community engaged research, clinical preceptor education, and practice‐based research.8

(2) Seven focus communities employ a Community Liaison, a community member who serves as the conduit, broker, and gatekeeper for academic–community research partnerships. Community Liaisons represent a new type of health research worker and combine elements of a research assistant, community health worker, grassroots organizer, bi‐directional advocate, and investigator. They are active in all aspects of the community engagement efforts and provide an essential voice to the PACT Council. A full description of the work of the Liaison is beyond the scope of this paper and a full description is forthcoming.

(3) A pilot grant program provides over $200,000 per year to campus–community partnerships working on innovative programs that address health disparities identified by the community. Pilot grants are reviewed and chosen by a PACT Council committee. More than 20 partnerships have developed new research endeavors leading to over $3 million in additional grants. For example, a partnership development grant in rural Colorado obtained a pilot grant to do home blood pressure monitoring. This led to improved blood pressure control. This program has now spread to a joint effort between the urban Center for African American Health and the rural High Plains Research Network which was funded by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to implement and disseminate the community inspired home blood pressure program in rural and urban communities. Pilot grant posters are presented at an annual campus‐community open house. Over 150 attend this annual event which has led to numerous new partnerships between academic researchers and community members.

(4) A vibrant educational program provides education and training for researchers and community members. Initially, a general overview workshop on community engaged and participatory research was developed for all pilot grant awardees including community and academic members. This 1‐day seminar has been successfully implemented with over 98 participants.

Figure 1.

Graphic depiction of the PACT and Community Engagement Core.

Two graduate level courses have been developed for broader dissemination on the principals of community engagement. The first is a seminar series that includes lectures, videos, and small group sessions. Twelve sessions are held each year and graduate students can sign up to attend and receive graduate level credit. Seminars are also open to the community and recordings posted on the CCTSI website. The second course is the Colorado Immersion Training (CIT) course.

The CIT program provides an intensive longitudinal experience for researchers to develop and strengthen community‐engaged research.9 The CIT includes three major components: a formal reading list, a 1‐week intense immersion experience in one of six community tracks throughout Colorado, and 4–6 months of follow‐up and relationship building. The initial reading list is provided in a formal on‐line format over 1 month and includes general community engagement and participatory research literature as well as track‐specific readings. Literature includes peer‐reviewed manuscripts, books, literary work, and video unique to each track community and culture.10 The 1‐week intensive begins with a half‐day seminar on community engagement followed by placement in a local community for the remainder of the week. Current communities include the Denver Latino(a) community, the Denver African‐American community, the Denver Asian and refugee community, the Denver Native American community, the San Luis Valley in rural southern Colorado, and the High Plains Research Network in rural and frontier eastern Colorado.

(5) A data acquisition, monitoring, and display program will provide locally relevant actionable data to communities. Two data‐blasts in PACT communities provide a comprehensive description of the health and healthcare needs for our urban Center for African American Health and the rural San Luis Valley. A collaborative data‐sharing document guides the work of our data programs.

Discussion

The CCTSI and PACT have undergone major transformative growth in their first 5 years. The PACT serves as a foundational platform for a dynamic (re)assortment of research efforts aimed at eliminating health disparities in Colorado. By forming the supportive scaffolding and infrastructure to develop and sustain Communities of Solution, the CCTSI and PACT are well down the road toward addressing health disparities.11 This infrastructure may represent an immerging technology necessary to truly eliminate health disparities in the United States. The PACT development and current activities may be of particular interest to those planning to submit proposals to the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) or the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

The PACT Council represents a new foundational infrastructure to translate generalizable knowledge to the local community where it matters most. Building trust and balancing power takes consistency over time, and does not just leap into existence. The founding PACT members started with mud on their boots and the PACT Council traded on their reputations and prior experience. Each critical shift was an inflection point on the trajectory of the PACT enterprise. The arc of the work is no longer just one CTSA grant to the next. The PACT represents a fundamental change in how academics and communities do research together, an exemplar of an emerging research structure and approach called out decades ago, with an opportunity to gain traction in over 60 CTSAs. The PACT work represents an opportunity for health science centers to identify populations in their vicinity to partner with, as together they accept responsibility to measure and improve health.

We have discovered a few old truths along the way that bear reiterating. Community engagement takes time. Community members have a life outside of research and healthcare. It is not their “day job” to complete all the work necessary to move research from idea to protocol to implementation. Community members are not researchers. While eager to learn and participate, it takes time to learn basic research methods, IRB and HIPAA regulation, and meet the host of university researchers interested in collaborating. Likewise, many academic researchers are marginally funded and must give first priority to current funded projects. Finding time to leave the campus and travel out into the community can be difficult to arrange and may take several visits before any relationship can even begin. But time is not the enemy. This long process also provides the foundation for a strong relationship. The PACT and PACT Council are not here and gone; they are in it for the long haul, and the strength of relationship is more important than the number of relationships or rapidly deployed programs.

As noted in previous work and literature, the early development of the PACT and PACT Council included lots of listening.12, 13, 14 Early meetings included a few structured elements, and lots of time for the community members to provide input, air grievances, educate the other members, and provide their vision for what an important organization might do. The listening extended into all aspects of the PACT work including numerous individual and group meetings with the Community Liaisons, PACT Council members, scientific staff, and other university and community members.

Listening required several explicit components that continue to require careful attention. First, there must be a safe venue for conversation. PACT Council meetings are physically structured around a large table so that all have an opportunity to speak and be heard. Initial meetings provided just enough room for PACT Council members. It became clear that open meetings that engaged other members of the Community Engagement Core including staff and community liaisons could be more successful, so the table was expanded, literally as well as figuratively. More than the physical structure was the cultural shift for the university faculty and staff to be silent and allow community members time to formulate and speak their words. This has been easy for some and more difficult for others. Second, the Chair, Vice‐Chair (currently a community member) along with the staff and Core Director meet with PACT Council members individually to provide further opportunity for members to openly discuss ideas and concerns. These meetings have taken many forms including visits to a member's home or work, or even one‐on‐one guided campus tours. These meetings have led to some initially quiet members becoming much more comfortable speaking at PACT Council meetings. Third, there must be topics worthy of conversation. Early meetings required delays about PACT Council structure, by‐laws, and governance issues, in lieu of conversations about purpose, meaning, and concepts of health equity. As the group developed, the formal conversations about PACT governance successfully melded the community voice with the university structure. Now, meetings include a formal agenda that provide a framework for conversation, necessary decision items, and plenty of flexibility to adapt to the speaking and listening needs of the group. A full transcription of our first retreat provided PACT Council members a permanent record for review and reflection.

The PACT Council has moved its meeting to various locations around the community so that community members are not always required to come to the large Anschutz Medical Campus of the University of Colorado Denver. One very successful meeting occurred in Ft Morgan, Colorado, 90 miles east of Denver. The local Country Club dining room served as the venue for the meeting and required the University faculty and Community Engagement Core Scientific Staff to travel to unfamiliar surroundings. The community members were right at home. Other meetings have been held at PACT Council member organizations including Kaiser, Denver Health, and 2040 Partners for Health. The PACT Council actively solicits invitations to meet in off‐campus sites.

The PACT Pilot Grant program requires every grant have a community partner and that at least half of the resources go to the community partner. This moves the research further out into the community as the community partners have control of their budget. As resources move into the community, academic researchers are more likely to travel into the community.

The flip side of leaving campus involves bringing more community members to campus to explore and learn of the clinical, educational, and research work occurring on campus. “Campus immersions” lasting 1–3 days, have brought more than 50 community leaders and members to campus to tour the facilities, meet with basic and clinical scientists, and participate in educational programs such as the Center for Advanced Professional Excellence (CAPE), the University simulation labs. Participants report new and broader understanding of the scientific process, academic demands, and the numerous research programs active on campus. These “immersions” have demystified the campus and made it a much more friendly and accessible place for participating community members. Frontiers in Medical Science is an evening weekly science research session offered for 6–8 weeks in the Spring. Each discussion covers a common clinical topic and addresses the related state of the science research. Genetics, cancer, and cardiovascular disease have been popular topics and each week for 2 months, 80–100 community members gathered to learn and discuss with a campus researcher.

Conclusion

The PACT Council underwent significant growth and development over 5 years, punctuated by quantifiable critical shifts. The critical shifts changed the trajectory of the development and work of the PACT Council. The PACT Council has explicitly chosen to exist for the long‐haul, and has chosen to continue even if CTSA funding is eliminated. Their decision to collectively pursue additional funding positions them as a stable and enduring organization. Since 2008, the PACT Council and CE Core staff have submitted multiple collaborative grants and have secured $2,115,500 in extramural grant funding to support our shared research agenda. The early goal of the CCTSI was to transform the translational research enterprise at the University of Colorado. The critical shifts we report and the outcomes from those shifts provide evidence of sustainable transformation in Colorado. The critical shifts were often not predictable or obvious. They required risk and engagement by community members, academic researchers, and CCTSI leadership. With support and participation from all these people, transformation in the translational research enterprise can provide the foundation for campus‐community efforts to improve health.

Acknowledgment

Supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000154. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

References

- 1. National Institutes of Health . RFA‐RM‐07‐007: Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award(U54). RFA‐RM‐07‐007 2007 March 22. Available from: http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfafiles/RFA‐RM‐07‐007.html. Accessed April 2008.

- 2. Minkler M. Community‐based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005; 82(2S2): ii3–ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community‐based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998; 19: 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, Lopez J, Butz A, Mosley A, Coates L, Lambert GP. Community‐based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005; 113(10): 1463–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seifer S, Shore N, Holmes S. Developing and Sustaining Community‐University Partnerships for Health Research: Infrastructure Requirements. Seattle, WA: Community‐Campus Partnerships for Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Macaulay AC, Commanda LA, Freeman WL, Gibson N, McCabe ML, Robbins CM, Twohig P. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. BMJ. 1999; 319: 774–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Main DS, Felzien MC, Magid DJ, Calonge BN, O'Brien RA, Kempe A, Nearing K. A community translational research pilot grants program to facilitate community‐academic partnerships: lessons from Colorado's clinical translational science awards. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012. Fall; 6(3): 381–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Westfall JM, Ingram B, Navarro D, Magee D, Niebauer L, Zittleman L, Fernald D, Pace W. Engaging communities in education and research: PBRN's, AHEC, and CTSA. Clin Trans Sci. 2012; 5: 250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zittleman L, Wright L, Barrientos Ortiz C, Fleming C, Loudhawk‐Hedgepeth C, Marshall J, Ramirez L, Wheeler M, Westfall JM. Colorado immersion training in community engagement: because you can't study what you don't know. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carillo JE, Ananeh‐Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003; 118: 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lesko S, Griswold K, David SP, Bazemore A, Duane M, Morgan T, Westfall JM, Koop CE, Garrett B, Puffer J, Green L. Communities of solution: the Folsom Report revisited. Ann Fam Med. 2012; 10: 250–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katz DL. Representing your community in community‐based participatory research: differences made and measured. Prev Chron Dis 2004; 1(1): A12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braithwaite R, Bianchi C, Taylor SE. Ethnographic approach to community organization and health empowerment. Health Educ Q. 1994; 21(3): 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Metzler M, Higgins D, Beeker C, Freudenberg N, Lantz P, Senturia K, Eisinger A, Viruell‐Fuentes E, Gheisar B, Palermo A, et al. Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City and Seattle through community‐based participatory research partnerships. Am J Public Health. 2003; 93: 803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]