Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the influence of parents and peers on adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors, framed by Primary Socialization Theory.

Design and Method

Longitudinal data collected annually from 1,081 rural youth (mean age = 17 ±.7; 43.5% males; 44% Hispanic) and once from their parents were analyzed using generalized linear models.

Results

Parental monitoring and adolescent’s religious commitment significantly predicted all health-promoting behaviors (nutrition, physical activity, safety, health practices awareness, stress management). Other statistically significant predictors were parent’s responsiveness and health-promoting behaviors. Peer influence predicted safety and stress management.

Practice Implications

Nurses may facilitate adolescents’ development of health-promoting behaviors through family-focused interventions.

Search terms: Adolescence, health behaviors health promotion, parental monitoring, primary socialization, religiosity

Although the major threats to health and life during adolescence are related to a few preventable health-risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking alcohol, using illicit drugs), engaging in health-promoting behaviors can lead to a number of immediate and long-term positive health outcomes (Pender, Murdaugh, & Parsons 2010). Health-promoting behaviors such as physical activity and eating foods low in fat have been shown to protect adolescents from adverse health outcomes (Hayman & Reineke, 2003; Johnson, Li, Galati, Pedersen, Smyth, & Parcel, 2003) and contribute to a healthy lifestyle over time (Kelder et al., 2003). Engaging in a healthy lifestyle during adolescence may prevent cardiovascular disease and cancer later in life (Grunbaum, Lowry, & Kann, 2001). The influence of friends on adolescents’ unhealthy behaviors is well-established, as are the protective effects of parent connectedness against risky behaviors, but the influence of friends and parents on adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors is examined less frequently. In the present study, we focus on the influence of parents’ and peers’ health behaviors and social connectedness of caring adults and friends on health-promoting behaviors in adolescents, and we provide evidence that should facilitate the development of health-promoting behaviors through family-focused interventions.

Although parents may provide verbal messages about the inherent dangers of engaging in risky health behaviors (Ford, Davenport, Meier, & McRee, 2011), their own actions often model behaviors that their children then imitate (Griesler & Kandel, 1998). Pender and colleagues’ (2010) conceptualization of health-promoting behavior posits that behavior is learned from observing and interacting with other people in one’s social environment. These nurse scientists (2010) proposed that a person is more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors when significant people such as family members and peers model that behavior and provide social support to facilitate such behaviors. Parents, by virtue of their central position in the social environment of the developing adolescent, play an important role in modeling health-promoting or health-risking behaviors. Parental monitoring, which includes knowing where children are when not in school, and parental religious practices have been shown to protect young adolescents from dating violence (Howard, Qiu, & Boekeloo, 2003). Parenting style, which includes parents’ responsiveness to and demandingness of their children, has been shown to protect adolescents from engaging in health-risk behaviors (Stephenson, Quick, Atkinson, & Tschida, 2005).

Peers also influence adolescents’ health behaviors (Dornelas et al., 2005; Wills, Gibbons, Gerrard, Murry, & Brody, 2003). For example, positive peer influences and social connectedness are related to adolescents’ positive health behaviors (Bruening et al., 2012). Less is understood, however, concerning the influence of parents’ own health behaviors and their parenting styles on their children’s health behaviors. Some have suggested that authoritative parenting styles (Milevsky, Schlechter, Netter, & Keehn, 2007) and engaging in organized religious activities (Haglund & Fehring, 2010; Manlove, Terry-Humen, Ikramullah, & Moore, 2006) may protect adolescents from engaging in health-risk behaviors. Protective factors within the family such as warmth, caring, and appropriate supervision have been cited as the most potent forms of protection, particularly within the Latino culture (Prado et al, 2007).

How parenting style and parents’ monitoring and health-related behaviors influence their adolescent children’s participation in developing specific health-promoting behaviors therefore remains unclear. Few studies have examined parents as role models of health-promoting or self-care behaviors for their adolescent child’s health-related behaviors. The present study was undertaken (a) to determine the influence of parents’ self-care behaviors and parenting behavior on health-promoting behaviors of their adolescent children and (b) to determine the influence of selected parenting behaviors (i.e., parenting style, parental monitoring, and parents’ religious commitment) as well as adolescents’ perceptions of other influences (i.e., social connectedness, peers, and religious commitment) on the adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors.

Background

Social learning theories of human development suggest that most human behaviors are learned within a social context that includes family, school, socializing institutions such as organized religions, and other supportive community organizations (Bandura, 1986; Bronfenbrenner, 1989; Lerner, 2002; Lerner & Castellino 2002). Studies of adolescent health over the past two decades have been dominated by a focus on health-risk behaviors, conceptualized as problem or deviant behaviors that tend to cluster together (Dishion, Ha, & Véronneau, 2012). Far fewer have focused on health-promoting or self-care behaviors of adolescents.

Few studies have examined the direct influence of parents’ behaviors on the development of adolescent health-promoting behaviors. In response to the Surgeon General’s 1979 report on health promotion and disease prevention, Pender introduced the health promotion model in 1982. This model served as a framework to integrate behavioral science and nursing perspectives on how to motivate persons to engage in behaviors that would enhance their overall health and quality of life (Pender et al., 2010). Subsequently, only a few nurse scientists have applied this perspective to the study of adolescent health behaviors (Srof & Velsor-Friedrich, 2006).

Conceptual Framework

Primary Socialization Theory (PST) is a social learning theory that posits that normative behaviors are learned in social contexts and are influenced by bonding with primary sources of socialization, such as family, school, and peers (Oetting & Donnermeyer, 1998). PST theorists assert that “adolescence is a particularly crucial time, a time when the potential for learning deviant norms is at its highest level” (Oetting, Deffenbacher, & Donnermeyer, 1998, p. 1338). Not only do parents have a large impact on their children’s behavior through parenting styles and monitoring that develop strong or weak family ties, these relationships influence the degree to which the developing adolescent will bond with deviant peers and engage in risky behaviors. Community influences such as religious institutions and schools may also affect healthy versus deviant behavior in youth by strengthening or weakening the bonds with the primary socialization units (Oetting, Donnermeyer, & Deffenbacher, 1998).

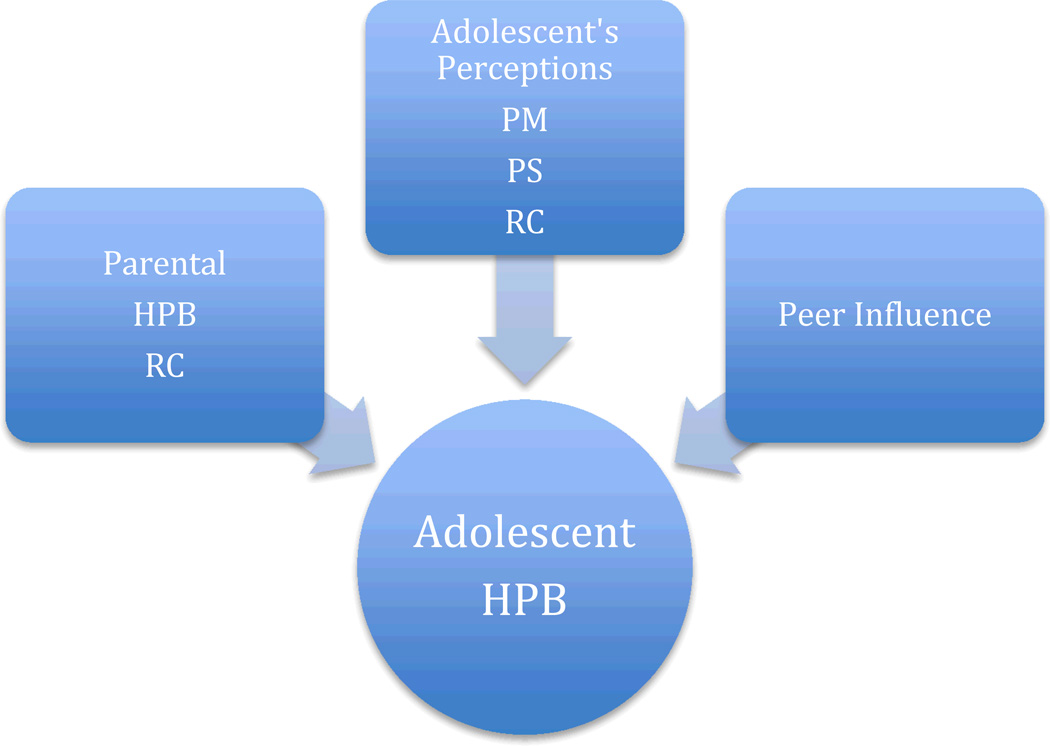

Although this theory has been used predominantly to explain the development of deviant behavior such as substance use in adolescents, we adapt it here to examine the influences of parental behaviors (modeling self-care and religious commitment and associated activities), the adolescent’s perceptions of those behaviors (parenting style and parental monitoring), and the influence of peers on the development of health-promoting behaviors of adolescents. Figure 1 depicts the proposed factors from parents’ health-promoting behaviors (HPB) and religious commitment (RC), the adolescents’ perceptions of their parents’ monitoring (PM) and parenting style (PS), as well as their own religious commitment (RC), and the influence from peers on the adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors.

Figure 1.

Relationships among parental and peer influences on adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors framed by Primary Socialization

Note: HPB = health-promoting behavior; RC = religious commitment; PM = parental monitoring; PS = parenting style.

Health-promoting behaviors

Health-promoting behaviors include actions taken by a person to commit to and facilitate a healthy lifestyle (Leddy, 2003). One study of nearly 2,000 pre-adolescents (Rew, Horner, & Fouladi, 2010) found that health-promoting behaviors significantly decreased over time and were exhibited more frequently by girls than boys. These behaviors were significantly and positively related to school engagement, social connectedness, and social acceptance. In contrast, several studies have shown that health-risk behaviors increase from early to late adolescence (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Hooshmand, Willoughby, & Good, 2012).

The literature pertaining to the influence of parents’ health-related behaviors on those of their children is sparse. In one study, young adolescent children (mean age 11.23 ± .96) whose parents helped them with their homework and who felt close to their children were more likely than those less connected with their parents to exhibit prosocial behaviors such as helping others (Day & Padilla-Walker, 2009). After conducting a systematic literature review about correlates of physical activity among adolescents, Sallis, Prochaska, and Taylor (2000) concluded the evidence was inconclusive regarding whether parental physical activity influenced adolescents’ physical activity. Findings from these studies are equivocal concerning the direct influence of parents’ health-related behaviors on those of their children.

Parenting style

Four distinct types of parenting styles, based on characteristics such as responsiveness and demandingness, are used to describe how parents interact with their children; these four types include authoritative, authoritarian, permissive/indulgent, and neglectful parenting (McKinney, Donnelly, & Renk, 2008; Milevsky et al., 2007. An authoritative parenting style is demonstrated through warmth and responsiveness rather than permissiveness or neglect. Such a parent is engaged with the child, maintaining healthy communication through high levels of support and adaptable control (McKinney et al., 2008).

An authoritarian parenting style, however, demonstrates high levels of control and harsh disciplinary methods. Because parents using this style are less responsive and highly demanding of their children, their children often rebel and do not respond favorably (McKinney et al., 2008; Milevsky et al., 2007). Permissive/indulgent parenting is highly responsive to children’s wants and needs but demands little in terms of expectations; neglectful parenting is neither responsive nor demanding (Jackson, Henriksen, & Foshee, 1998). Non-authoritative parenting has been implicated in adolescent health-risk behaviors (Newman, Harrison, Dashiff, & Davies, 2008).

Parental monitoring

Parental monitoring refers to a parent’s being involved in his or her child’s life, having knowledge of and monitoring the child’s whereabouts, and providing a consistent, balanced level of discipline (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). Parental monitoring and supervision from an authoritative perspective can serve to protect adolescents from engaging in health-risk behaviors (Huebner & Howell, 2003). Among a nationally representative sample, Videon and Manning (2003) found higher fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents who reported having more than three meals per week with their parents.

Religiosity

Religiosity and cultural values have been suggested as important factors in the development of adolescent self-regulatory behaviors, but this topic has been rarely illuminated by empirical research (Abar, Carter, & Winsler, 2009). Abar et al. (2009) studied 85 older African American adolescents and found that maternal religiosity was not significantly related to adolescent health-risk behaviors such as smoking tobacco or marijuana and using drugs or alcohol.

Although religiosity has been identified in studies as a protective factor in adolescent health-risk research (Manlove et al., 2006; Wray-Lake et al., 2012), the impact of these studies has been limited by a lack of consistency in theoretical and operational definitions of these terms. For example, terms such as “religious involvement” (Regnerus, 2003), ”religious practices” (Barry & Nelson, 2005), and “how often do you attend religious services?” (Hull, Hennessy, Bleakley, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2011) have all served as operational definitions for the general phenomenon of “religiosity.” Moreover, many of these studies are further limited by the reliance on single-item measures or scales with no reported reliability or validity data (Rew & Wong, 2006). Many studies of the protective nature of religiosity have focused on college students rather than younger adolescents (Abar et al., 2009; Barry & Nelson, 2005).

Peer influences and social connectedness

Peers may influence friends through modeling health-risk behaviors, such as substance use, and changing norms that support these behaviors (Dornelas et al., 2005). In a rare study comparing adolescents (ages 13–16) with youth (ages 18–22), and adults (ages 24 and older), Gardner and Steinberg (2005) found that younger participants (i.e., adolescents and youth) were more likely than adults to engage in risky behaviors with a group of peers rather than when alone.

Social connectedness is the perception that one can reliably count on others to provide emotional and instrumental support (Frauenglass, Routh, Pantin, & Mason, 1997). Perceived social connectedness that aligns caring adults with vulnerable children has been identified as a critical resource in protecting adolescents from an array of poor developmental and health outcomes (Henrich, Brookmeyer, & Shahar, 2005; Regnerus & Elder, 2003). It remains unclear whether or not social connectedness relates to adolescent health-promoting behaviors.

In sum, most adolescent health research addresses the health-risk behaviors of adolescents as opposed to their health-promoting behaviors. Consistent protective factors against health-risk behaviors include parenting factors (e.g., parenting style, parental monitoring), religiosity, social connectedness, and peer influence. In contrast, however, very little is known about whether these same variables may relate to adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors.

Method

Design and Setting

This study is a component of a cohort-sequential longitudinal study of the development of health behaviors in middle adolescence. The approach includes strengths of both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs and allows the researcher to examine complex trajectories of behaviors that change over time. This design is characterized by repeated measures that allow for identifying intra- and inter-individual change in development (Nesselroade & Baltes, 1979). The study took place in rural areas of central Texas where the population of Hispanics, most of Mexican descent, is rapidly increasing.

Sample

The analytic sample for this study comprises the latest available records of 1,081 participants in the main study who provided data in their junior and senior years in high school. These data were collected from 2009–2012. Parents of these adolescents provided their own health-promoting behavior and religiosity data included in this analysis when the adolescents enrolled in the study as freshmen in high school.

Protocol

The University’s Human Subjects and Institutional Review Board approved the longitudinal study of health behaviors in middle adolescence annually throughout the study. Parents received a written letter describing the purpose and plan for data collection when their children enrolled in the study as freshmen. Each year parents provided written consent and adolescents under the age of 18 years provided written assent. All letters and research instruments were available in both English and Spanish languages.

During the first 2 years, data were collected via laptop computers in the participants’ homes. Parents and adolescents were asked to sit in separate rooms, where possible, or a reasonable distance apart if in the same room to maintain privacy during data collection. Trained graduate research assistants (GRAs) traveled to homes of participants to collect data and answer any questions about the procedure. In the last 3 years of the study, when participants were unable to provide a time for GRAs to make home visits, data were collected through paper surveys mailed to the participants. Participants responded to the same battery of measures each of the years they were enrolled in the study.

Measures

A battery of 18 valid instruments was used to measure the variables of interest annually in the longitudinal study. For the purposes of this analysis, seven instruments were used to measure parental monitoring, parenting style, the parent’s health-promoting behaviors, religious commitment, social connectedness, peer influence, and the adolescent’s health-promoting behaviors. Parents provided data about demographics, their own religious commitment, and their own health-promoting behaviors; adolescents provided data about their perceptions of parental monitoring, parenting style, social connectedness, peer influence, religious commitment, and health-promoting behaviors. The same measure of religious commitment was used by both parents and adolescents. Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha for each of the measures for this sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Cronbach’s Alpha (α) of Scales Measuring Parent and Adolescent Behaviors

| Predictor Variables | n | Mean | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Monitoring | 995 | 31.0 | 6.0 | .83 |

| Parenting Responsiveness | 991 | 26.2 | 6.1 | .88 |

| Parenting Demandingness | 992 | 19.5 | 4.6 | .82 |

| Parent’s Health-promoting Behaviors | 990 | 130.1 | 11.2 | .81 |

| Parent’s Religious Commitment | 984 | 29.5 | 12.8 | .96 |

| Adolescent’s Religious Commitment | 994 | 21.4 | 11.0 | .96 |

| Adolescent’s Social Connectedness | 1001 | 31.7 | 5.6 | .77 |

| Adolescent’s Peer Influence | 1001 | 66.1 | 9.3 | .91 |

| Outcome Variables | ||||

| Nutrition | 998 | 25.0 | 8.3 | .90 |

| Physical Activity | 998 | 13.9 | 6.4 | .89 |

| Safety | 998 | 35.8 | 6.3 | .78 |

| Health Practices Awareness | 998 | 11.7 | 4.7 | .75 |

| Stress Management | 998 | 14.3 | 4.6 | .66 |

Parenting styles

The adolescent’s perception of their parents’ style was measured with the Authoritative Parenting Index (API), which consists of 16 statements with a 4-point response format (Jackson et al., 1998). The API comprises two subscales: responsiveness and demandingness. An example of responsiveness is “She listens to what I say”; an example of demandingness is “She has rules that I must follow.” Authoritative parenting refers to a style that is high in both responsiveness and demandingness (Jackson et al., 1998).

Parental monitoring

Parental monitoring, including knowing where one’s children are, who they are with, and setting boundaries (Windle et al., 2010), was measured with an eight-item scale (Huebner & Howell, 2003). This scale had a 5-point Likert response format (e.g., 0 = never; 4 = very often) and sample items included “My parent(s) know who my friends are,” and “My parent(s) monitor my computer/Internet use.” High scores indicated greater social connectedness than low scores.

Parent’s health-promoting behaviors

Health-promoting behaviors of the parent were measured with the Self-Care Inventory (Pardine, Napoli, & Dytell, 1983; Walker et al., 2004). The scale consists of 40 items with a 4-point Likert response format (e.g., 0 = rarely or never; 3 = very often). Examples are “During the past month, how often did you eat a nutritious breakfast?” and “During the past month, how often did you practice good oral hygiene care (e.g., brushed and flossed your teeth?)” High scores indicated greater health-promoting behaviors than low scores.

Religious commitment

Religious commitment reflected the congruence of an individual’s religious beliefs, values, and activities of daily living (Worthington et al., 2003, p. 85). It was measured with the Religious Commitment Inventory (Worthington et al., 2003), which consists of 10 items with a 5-point Likert response format (e.g. 1 = not at all true of me; 5 = totally true of me). Examples are “I spend time trying to grow in understanding of my faith” and “I enjoy spending time with others of my religious affiliation.” High scores indicated greater religious commitment than low scores. Both parents and adolescents completed the same measure.

Adolescent social connectedness

Social connectedness, which reflected the adolescent’s perception that s/he could depend on other people for instrumental and emotional support, was measured with the Family Integration Scale (Blum, Harris, Resnick, & Rosenwinkel, 1989). This scale was initially part of the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey. It consists of 10 items with a 4-point Likert response format (e.g., 1 = none; 4 = very much). Items indicate how much one believes that adults and peers care about her/him. Examples are “How much do you feel that school people care about you?” and “How much do you feel that you and your family have lots of fun together?” High scores indicated greater social connectedness than low scores.

Adolescent’s peer influences

Peer influence indicates how many of the adolescents’ friends engage in health-risk behaviors such as smoking and drinking, and how often these friends have asked them to engage in these same behaviors. The Peer Influence Scale (Williams, Toomey, McGovern, Wagenaar, & Perry, 1995) contains 15 items with a 5-point Likert response format (e.g., “Please tell us how many of your friends drink alcohol” 1= none, 5 = almost all of them. “How often have your friends asked you to drink alcohol? 1 = never, 5 = many times). Higher scores indicated more influence from peers to engage in health-risk behaviors.

Adolescent’s health-promoting behaviors

The dependent variables for this study were measures of health-promoting behaviors or actions taken by an adolescent to improve general health and well-being. These adolescent outcome behaviors were measured with five subscales of the Adolescent Lifestyle Questionnaire (ALQ; Gillis, 1997). The ALQ contains seven subscales consisting of 43 items with a 6-point Likert response format (e.g., 1 = never; 6 = always). For this analysis, we used only five of the subscales that measured nutrition (NU), physical activity (PA), safety (SAF), health practices awareness (HA), and stress management (SM). Sample items include “When riding in an automobile, I wear a seatbelt” [SAF]; “I talk to my friends about my stress” [SM]; “I read pamphlets, teen magazines about health topics of interest” [HA]; “I play sports at least 3 times per week” [PA]; and “I usually choose foods without additives” [NU]. The two other subscales, identity awareness and social support, did not conceptually reflect health-behaviors of the adolescent per se and were not used in this analysis.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Descriptive statistics consisting of means and standard deviations for continuous data and frequencies and percents for categorical data were computed. Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha for the adolescent behavior outcome scales, the adolescent predictor scales, and the parental predictor scales are reported in Table 1. Table 2 is a correlation matrix of all variables in this analysis. Generalized linear models (GLM) were computed. Each least squares regression model included the adolescent’s age, race/ethnicity, and gender, plus parent’s marital status, and participation in subsidized school lunch program to control for their possible confounding effects; the adolescent and parental predictors were eliminated in a step-wise backward elimination procedure until all predictors were significant at the .05 probability level. The absolute value of the standardized estimates is interpreted as the relative importance of the variable in the regression equation.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Primary Socialization Variables and Adolescent Health-promoting Behaviors

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NU | .333** | .298** | .475** | .442** | .147** | .052 | .144** | .197** | .054 | .130** | .129** | .068* | |

| 2 PA | .233** | .212** | .382** | .177** | .080* | .185** | .197** | .077* | .216** | .142** | .063* | ||

| 3 SAF | .345** | .364** | .242** | .283** | .320** | .449** | .515** | .324** | .122** | .136** | |||

| 4 HPA | .551** | .232** | .247** | .235** | .310** | .125** | .369** | .065* | .049 | ||||

| 5 SM | .425** | .229** | .236** | .290** | .076* | .344** | .089* | .210** | |||||

| 6 ARC | .152** | .197** | .213** | .149** | .246** | .100* | .500** | ||||||

| 7 API R | .267** | .338** | .187** | .633** | .117* | .063 | |||||||

| 8 API D | .626** | .248** | .340** | .140** | .103* | ||||||||

| 9 PM | .334** | .391**. | 140** | .115* | |||||||||

| 10 Peer | .232** | .061 | .089* | ||||||||||

| 11 SoCon | .137** | .128** | |||||||||||

| 12 PHPB | .190** | ||||||||||||

| 13 PRC | 1 |

Note.

p < .05;

p ≤ .001

1 = Nutrition; 2 = Physical activity; 3 = Safety; 4 = Health practices awareness; 5 = Stress management; 6 = Adolescent’s Religious commitment; 7 = Parenting responsiveness; 8 = Parent demandingness; 9 = Parental monitoring; 10 = Peer influence; 11 = Social connectedness; 12 = Parent’s health-promoting behaviors; 13 = Parent’s Religious commitment

Findings

The mean age of the 1,081 adolescents in the sample was 17 years (SD =.7). Males (n = 435) comprised 43.5% of the sample. The race/ethnic composition was 44% Hispanic (n = 449), 37.5% non-Hispanic White (n = 382), 12.4% non-Hispanic Black (n = 126), and 3% each other (n = 31), and unknown (n = 30). Grade levels were 20% juniors and 80% seniors. The means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas of the outcomes and predictors are shown in Table 1. Note that the sample size varies from 990 to 1001. Cases with missing data were eliminated from the analyses; therefore, the sample size for each regression shown in Table 3 will vary according to the missing data among the variables remaining in the final equation.

Table 3.

Adolescent Health Behaviors Regressed on Demographics and Parent and Adolescent Predictors.

| Predictor Variables | Health Behaviors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition (n = 938; R2 =.10) | ||||

| b | SE | Partial r | p | |

| Parental Monitoring | .22 | .05 | .14 | < .001 |

| Parent Responsiveness | −.13 | .07 | −.07 | .048 |

| Adolescent’s Social Connectedness | .13 | .06 | .07 | .048 |

| Adolescent’s Religious Commitment | .09 | .03 | .11 | .001 |

| Parent’s Health-promoting Behavior | .06 | .02 | .08 | .022 |

| Physical Activity (n = 938; R2 =.17) | ||||

| b | SE | Partial r | p | |

| Adolescent’s Social Connectedness | .23 | .25 | .15 | < .001 |

| Parental Monitoring | .14 | .04 | .13 | < .001 |

| Parent Responsiveness | −.11 | .04 | −.07 | .008 |

| Adolescent’s Religious Commitment | .08 | .02 | .14 | < .001 |

| Parent’s Health-promoting Behavior | .04 | .02 | .09 | .024 |

| Safety (n = 938; R2 =.40) | ||||

| b | SE | Partial r | p | |

| Adolescent’s Peer Influence | .27 | .02 | .44 | < .001 |

| Parental Monitoring | .25 | .03 | .26 | < .001 |

| Parent Responsiveness | .11 | .03 | .13 | < .001 |

| Adolescent’s Religious Commitment | .06 | .02 | .13 | < .001 |

| Health Practices Awareness (n = 945; R2 = 0.22) | ||||

| b | SE | Partial r | p | |

| Adolescent’s Social Connectedness | .23 | .03 | .26 | < .001 |

| Parental Monitoring | .23 | .03 | .16 | < .001 |

| Adolescent Religious Commitment | .05 | .01 | .12 | < .001 |

| Stress Management (n = 945; R2 =.28) | ||||

| b | SE | Partial r | p | |

| Adolescent Religious Commitment | .14 | .01 | .35 | < .001 |

| Adolescent’s Social Connectedness | .19 | .03 | .23 | < .001 |

| Parental Monitoring | .11 | .02 | .14 | < .001 |

| Adolescent’s Peer Influence | −.05 | .01 | −.10 | .002 |

b = regression coefficient, SE = standard error, R2 = multiple correlation. Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, and grade level.

Table 3 shows the regression coefficients (b) adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, and grade level. Each type of adolescent health-promoting behavior (i.e., nutrition, physical activity, safety, health practices awareness, and stress management) was regressed on predictors of parental monitoring, parenting style (responsiveness and demandingness), parent’s health-promoting behaviors, religious commitment of adolescent and of parent, and adolescent social connectedness and peer influence.

Parent predictor variables

Parental monitoring was a significant predictor for each of the behavior domains and ranged from partial correlation of .13 for physical activity to .26 for safety behaviors. Parenting responsiveness style was a significant predictor for safety, and nutrition, but it was not a significant predictor for the other types of health-promoting behaviors. Parenting demandingness was not retained in any of the regression equations. Parenting responsiveness was positively associated with safety but negatively associated with physical activity and nutrition. Parent’s health-promoting behavior was a significant predictor of nutrition, physical activity, and health practices awareness. Parent’s religious commitment was not used in the regression models because of collinearity (r = .50) with the adolescent’s religious commitment.

Adolescent predictor variables

Adolescent’s social connectedness was a significant predictor for all types of health-promoting behaviors except safety. Social connectedness contributed the largest partial correlation with physical activity and health practices awareness. Adolescent peer influence was a significant and positive predictor of safety behaviors but a negative and fairly weak predictor of stress management. Adolescent’s religious commitment was a significant but fairly weak predictor for four of the five types of health-promoting behaviors. Its greatest effect was on stress management.

Discussion

The present findings provide some support for the theoretical framework of primary socialization (Oetting et al., 1998). Clearly, parenting variables such as responsive parenting, parental monitoring, and parental health-promoting behaviors are associated with adolescents’ health-promoting behaviors. The parent’s health behaviors contributed less to the regression equations than did parental monitoring as a predictor of all adolescent behavior outcomes. Parent’s health behavior was not a significant predictor of safety, health practices awareness, or stress management. It may be that adolescents in this study perceived their parents’ concern about their social interactions (i.e., where they were, who they were with) to be more important than the health-promoting behaviors that parents modeled in their day-to-day living. Similarly, it may be that the scale used to measure the adolescent’s health-promoting behaviors focuses on self-directed behaviors and communication with friends and teachers rather than a focus on communication with parents about these behaviors.

Parenting style that is perceived as responsive is clearly more strongly related to an adolescent’s health-promoting behaviors than a style that is perceived as demanding. This finding is somewhat confusing when interpreted in the light of previous research indicating that parents who are both responsive and demanding (i.e., authoritative) represent a protective factor against health-risk behaviors in adolescents (Jackson et al., 1998). Based on our use of the Authoritative Parenting Index, we would have expected to see parenting responsiveness and parenting demandingness as similar significant predictors in the regression equations. It may be that as the adolescents in this study matured, they experienced less demandingness from their parents owing to the adolescents’ increased autonomy, but they retained the sense that these parents were still responsive to them. Moreover, the negative association of parental responsiveness with nutrition may suggest that parents who are highly responsive, as is the case among indulgent parents, foster poor nutrition through permissiveness. Further longitudinal study should be done to determine if these interpretations are valid.

Some adolescents may perceive parental monitoring as a parent’s lack of trust or support, but this interpretation warrants further investigation. Similarly, the perception of parental monitoring may add stress to an adolescent’s life and thus is counter-productive to adolescents’ stress management behaviors. This too warrants further investigation. It was surprising to find no significant relationship between parents’ health-promoting behaviors and those of adolescents in the domain of safety because many of the behaviors are the same, although worded slightly differently (e.g., use of seat belts when riding in a car, avoiding smoking and drinking alcohol). Perhaps safety behaviors such as use of seat belts have become so habitual by the time children become adolescents that any direct influence of parents is attenuated over time. These behaviors may also have become habits for their peers who might otherwise encourage them to engage in health-risk behaviors.

Social connectedness was significantly associated with all health-promoting behaviors among the adolescents in this sample except for safety. It was surprising to find a positive association between peer influence and any of the adolescent’s health-promoting behaviors because the measure of peer influence used in this study reflected peers who engaged in many health-risk behaviors (smoking, sniffing to get high, drinking alcohol, etc.) and who often asked the respondents to engage in these behaviors, whereas the ALQ used to measure the health-promoting behaviors eschewed engaging in such behaviors. It may be that peers who engaged in these behaviors and attempted to encourage the participants to engage in such behaviors actually motivated the participants to engage in the opposite type of behaviors. It may also be that peers who engage in other health-risk behaviors such as smoking and drinking nevertheless also engage in safety measures such as wearing seatbelts because such behavior has been habituated. In sum, the predictive influence of peers on safety and the negative influence on stress management are equivocal. This is an area for further exploration.

Adolescents’ religious commitment was significantly associated with each of the five health-promoting behaviors. This supports other findings that adolescents’ religiosity is significantly related to less engagement in health-risk behaviors such as smoking, drinking, risky sexual activities, and suicidal ideation (Sinha, Cnaan, & Gelles, 2007). Our results extend what is known about the protective effects of religiosity to the realm of health-promoting behaviors.

Parents’ health-promoting behaviors contributed significantly but modestly to adolescents’ physical activity and nutrition but not to adolescents’ safety, health practices awareness, or stress management. This was surprising; we expected this variable to be a strong predictor of all adolescent health-promoting behaviors. One of the stress management behaviors was talk to my friends about my stress, but no item suggested talking with parents, so the instrument itself may account for this finding. Similarly, the behaviors categorized in the ALQ as health practices awareness included talking to a teacher or nurse about ways to improve my health, and discuss health issues with others. However, these items did not include a direct reference to parents. Items categorized as safety (e.g., wear seatbelts in automobile) and nutrition (e.g., read food labels) suggest self-directed actions rather than actions involving relationships.

Limitations of this study included the reliance on self-reported variables from a convenience sample of adolescents and their parents. The study was limited to three rural areas in central Texas so findings are not generalizable to other demographic groups of adolescents. Nonetheless, the findings add to the growing literature demonstrating that adolescents’ perceptions of their parents and their parents’ health behaviors continue to influence the health-promoting behaviors of adolescents as they transition into and through high school.

Many of the findings of this study are new to the adolescent health literature. Until now, little research has focused on the direct influences of parents on the development of health-promoting behaviors in adolescents. The sample represents a high percentage of Hispanics, contributing new information about a demographic that is increasing in the United States. While much research remains to be done in this important area of health science, this study has shown that parents and religious commitment are important factors that contribute to the development of positive, health-promoting behaviors in adolescents. Parents who are responsive to the needs of their adolescent children, who monitor their adolescents’ activities, and who model healthy behaviors themselves remain influential as their children mature and are increasingly exposed to peers who might otherwise influence them to engage in health-risk behaviors.

Conclusion

The findings confirm that parenting behaviors and religious commitment remain significant sources of socialization for a diverse group of adolescents as they face the transition of completing high school. Health-promoting behaviors form a solid base on which adolescents may build a future healthy lifestyle.

How Might This Information Affect Nursing Practice

Evidence from this study suggests that further study is warranted to develop and test nursing interventions based on Primary Socialization Theory. Nonetheless, school nurses and pediatric nurse practitioners who work with adolescents and their families can reflect on the findings to better understand the relationships that adolescents continue to have with parents as well as peers. Nurses working in public health settings may also use the evidence to base their practices on recognizing that adolescents are forming health behaviors that are both health-promoting and health-risking. Nurses can incorporate a better understanding of the influence that both peers and parents have on the development of these health behaviors and how these may lead to a healthy lifestyle in early adulthood.

This study reinforces that, in this time of transition to greater independence, parents still matter to their adolescent children. Nurses are urged to remember that parents continue to influence adolescents and should be included in efforts to promote adolescents’ healthy behaviors. Nurses in settings that treat adolescents should assess the health behaviors of these youth and encourage parents to monitor their adolescent’s activities. Parents can also be reminded that they continue to be role models of health behaviors for their adolescent children. Moreover, parents and other caring adults who interact with adolescents in a variety of social settings can be reminded that the development of health-promoting behaviors in adolescence may lay an essential framework for a healthy lifestyle in adulthood.

Parish nurses whose careers have taken them into religious institutions may use the findings from this study as evidence from which to plan a family-centered health intervention. For example, these nurses might develop and initiate a brief program for adolescents and their parents to enhance their awareness of what defines health-promoting behaviors. Activities could include adolescents’ and parents’ values clarifications to underscore the importance of having a healthy lifestyle to ensure well-being. Another important component of such an intervention could be to provide anticipatory guidance about parenting an adolescent. This type of intervention is consistent with activities that are already frequently practiced by many parish nurses (Solari-Twadell, 2010).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NR0009856 to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest. Submissions from members of the journal’s editorial staff or editorial board receive double-blind peer review. Journal staff and editorial board members are not assigned to the review of or make decisions on manuscripts for which they are listed as authors.

Contributor Information

Lynn Rew, University of Texas at Austin, School of Nursing, Austin, TX, USA.

Kristopher L. Arheart, The University of Miami, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Miami, Florida.

Sanna Thompson, The University of Texas at Austin, School of Social Work, Austin, Texas.

Karen Johnson, The University of Texas at Austin, School of Nursing, Austin, Texas.

References

- Abar B, Carter KL, Winsler A. The effects of maternal parenting style and religious commitment on self-regulation, academic achievement, and risk behavior among African-American parochial college students. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CM, Nelson LJ. The role of religion in the transition to adulthood for young emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Blum R, Harris LJ, Resnick MD, Rosenwinkel K. Technical report on the adolescent health survey. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development. 1989;6:187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bruening M, Eisenberg M, MacLehose R, Nanney MS, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Relationship between adolescents’ and their friends’ eating behaviors: Breakfast, fruit, vegetable, whole-grain, and dairy intake. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112:1608–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RD, Padilla-Walker LM. Mother and father connectedness and involvement during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:900–904. doi: 10.1037/a0016438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Ha T, Véronneau M-H. An ecological analysis of the effects of deviant peer clustering on sexual promiscuity, problem behavior, and childbearing from early adolescence to adulthood: An enhancement of the life history framework. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:703–717. doi: 10.1037/a0027304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1(1):61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas E, Patten C, Fischer E, Decker PA, Offord K, Barbagallo J, Ahluwalia JS. Ethnic variation in socioenvironmental factors that influence adolescent smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CA, Davenport AF, Meier A, McRee A-L. Partnerships between parents and health care professionals to improve adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauenglass S, Routh DK, Pantin HM, Mason CA. Family support decreases influence of deviant peers on Hispanic adolescents’ substance use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(1):15–23. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Steinberg L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:625–635. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis AJ. The Adolescent Lifestyle Questionnaire: Development and psychometric testing. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 1997;29(1):d29–d46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB. The impact of maternal drinking during and after pregnancy on the drinking of adolescent offspring. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:292–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum JA, Lowry R, Kann L. Prevalence of health-related behaviors among alternative high school students as compared with students attending regular high schools. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:337–343. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund KA, Fehring RJ. The association of religiosity, sexual education, and parental factors with risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Religious Health. 2010;49:460–472. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman LL, Reineke PR. Preventing coronary health disease: The implementation of healthy lifestyle strategies for children and adolescents. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;18:294–301. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shahar G. Weapon violence in adolescence: Parent and school connectedness as protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooshmand S, Willoughby T, Good M. Does the direction of effects in the association between depressive symptoms and health-risk behaviors differ by behavior? A longitudinal study across the high school years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard D, Qiu Y, Boekeloo B. Personal and social contextual correlates of adolescent dating violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner AJ, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SJ, Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Identifying the causal pathways from religiosity to delayed adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:543–553. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.521868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:319–337. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CC, Li D, Galati T, Pedersen S, Smyth M, Parcel GS. Maintenance of the classroom health education curricula: Results from the CATCH-ON study. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30:476–488. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder SH, Mitchell PD, McKenzie TL, Derby C, Strikmiller PK, Luepker RV, Stone EJ. Long-term implementation of the CATCH physical education program. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30:463–475. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leddy SK. Integrative health promotion: Conceptual bases for nursing practice. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Adolescence: Development, diversity, context, and application. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Castellino DR. Contemporary developmental theory and adolescence: Developmental systems and applied developmental science. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:122–135. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove JS, Terry-Humen E, Ikramullah EN, Moore KA. The role of parent religiosity in teens’ transitions to sex and contraception. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C, Donnelly R, Renk K. Perceived parenting, positive and negative perceptions of parents, and late adolescent emotional adjustment. Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 2008;13(2):66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A, Schlechter M, Netter S, Keehn D. Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(1):39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR, Baltes PB, editors. Longitudinal research in the study of behavior and development. New York, NY: Academic Press; [Google Scholar]

- Newman K, Harrison L, Dashiff C, Davies S. Relationships between parenting styles and risk behaviors in adolescent health: An integrative literature review. Rev Latino-am Enfermagerm. 2008;16(1):142–150. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Deffenbacher JL, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory. The role played by personal traits in the etiology of drug use and deviance. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:1337–1366. doi: 10.3109/10826089809062220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Deffenbacher JL. Primary socialization theory. The influence of the community on drug use and deviance. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:1629–1665. doi: 10.3109/10826089809058948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardine P, Napoli A, Dytell R. Health behavior change mediating the stress-illness relationship. Annaheim, CA: Paper presented at the American Psychological Association; Aug, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, Szapocznik J. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD. Linked lives, faith, and behavior: Intergenerational religious influence on adolescent delinquency. Journal for Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD, Elder GH., Jr Staying on track in school: Religious influences in high and low-risk settings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:633–649. [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Horner SD, Fouladi RT. Factors associated with health behaviors in middle childhood. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2010;25:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Wong YJ. A systematic review of associations among religiosity/spirituality and adolescent health attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32:963–975. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC: 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013 from www.sas.com/software/sas9/ [Google Scholar]

- Sinha JW, Cnaan RA, Gelles RJ. Adolescent risk behaviors and religion: Findings from a national study. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:231–249. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari-Twadell PA. Providing coping assistance for women with behavioral interventions. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2010;39:205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srof BJ, Velsor-Friedrich B. Health promotion in adolescents: A review of Pender’s Health Promotion Model. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2006;19:366–373. doi: 10.1177/0894318406292831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson MT, Quick BL, Atkinson J, Tschida DA. Authoritative parenting and drug-prevention practices: Implications for antidrug ads for parents. Health Communication. 2005;17:301–321. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1703_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM, Manning CK. Influences on adolescent eating patterns: The importance of family meals. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32:356–373. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00711-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LO, Freeland-Graves J, Milani T, Hanss-Nuss H, George G, Sterling BS, Stuifbergen A. Weight and behavioral psychosocial factors among ethnically diverse low-income women after childbirth: I. Methods and context. Women & Health. 2004;40(2):1–17. doi: 10.1300/J013v40n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Toomey TL, McGovern P, Wagenaar AC, Perry CL. Development, reliability, and validity of self-reported alcohol-use measures with young adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1995;4(3):17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Murry VM, Brody GH. Family communication and religiosity related to substance use and sexual behavior in early adolescence: A test for pathways through self-control and prototype perceptions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:312–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Brener N, Cuccaro P, Dittus P, Kanouse DE, Murray N, Schuster MA. Parenting predictors of early-adolescents’ health behaviors: Simultaneous group comparisons across sex and ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:594–606. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington EL, Jr, Wade NG, Hight TL, Ripley JS, McCullough ME, Berry JW, O’Connor L. The Religious Commitment Inventory—10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50(1):84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake L, Maggs JL, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. Associations between community attachments and adolescent substance use in nationally representative samples. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]