Abstract

Autophagy degrades cytoplasmic proteins and organelles to recycle cellular components that are required for cell survival and tissue homeostasis. However, it is not clear how autophagy is regulated in mammalian cells. WASH (Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) and SCAR homologue) plays an essential role in endosomal sorting through facilitating tubule fission via Arp2/3 activation. Here, we demonstrate a novel function of WASH in modulation of autophagy. We show that WASH deficiency causes early embryonic lethality and extensive autophagy of mouse embryos. WASH inhibits vacuolar protein sorting (Vps)34 kinase activity and autophagy induction. We identified that WASH is a new interactor of Beclin 1. Beclin 1 is ubiquitinated at lysine 437 through lysine 63 linkage in cells undergoing autophagy. Ambra1 is an E3 ligase for lysine 63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1 that is required for starvation-induced autophagy. The lysine 437 ubiquitination of Beclin 1 enhances the association with Vps34 to promote Vps34 activity. WASH can suppress Beclin 1 ubiquitination to inactivate Vps34 activity leading to suppression of autophagy.

Keywords: Ambra1, autophagy, Beclin 1 ubiquitination, Vps34 activity, WASH

Introduction

Macroautophagy (herein referred to as autophagy) degrades cytoplasmic proteins and organelles to recycle cellular components that are required for cell survival and tissue homeostasis (Shintani and Klionsky, 2004; Lee et al, 2010; Bodemann et al, 2011; Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). During autophagy induction, double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes are produced to sequester intracellular cargos and fused with lysosomes to form autolysosomes for subsequent degradation. Many autophagy-related genes (Atg) have been identified and characterized in yeast and some of them are evolutionarily conserved (Nakatogawa et al, 2009; Egan et al, 2011). Deficiency of some Atg or Atg-related genes resulted in early embryonic lethality or death of neonates in mice (Yue et al, 2003; Kuma et al, 2004; Fimia et al, 2007).

Beclin 1, a homologue of the Atg6/vacuolar protein sorting (Vps)30 protein in yeast, was first identified as a Bcl-2 interacting protein. Bcl-2 sequesters Beclin 1 from the core Beclin 1–Vps34 complex and inhibits autophagy (Pattingre et al, 2005). Beclin 1 is critical for localization of autophagic proteins to a preautophagosomal structure (PAS) through interaction with the class III phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3KC3/Vps34) (Weidberg et al, 2011). Vps34 can phosphorylate the D-3 position on the inositol ring of phosphatidylinositol to generate phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), which is essential for recruiting other regulatory factors to the site of autophagosome formation (Miller et al, 2010). Beclin 1 association with Vps34 was reported to be regulated through their post-translational modifications or other protein partners (Fimia et al, 2007; Takahashi et al, 2007; Zalckvar et al, 2009; Furuya et al, 2010; Shi and Kehrl, 2010). However, it is unclear how Vps34 activity is regulated in the process of autophagy.

WASH (Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) and SCAR homologue) is a recently identified member of the WASP family (Linardopoulou et al, 2007). WASH plays an essential role in endosome sorting through facilitating tubule fission via Arp2/3 activation (Derivery et al, 2009; Gomez and Billadeau, 2009). These reports showed that WASH is an endosomal protein that exists in the FAM21-containing multiprotein complex. However, its real in vivo roles have not been defined yet. Here, we demonstrate a novel function of WASH in modulation of autophagy. We found that WASH deficiency causes early embryonic lethality and extensive autophagy of mouse embryos. WASH is a negative regulator of autophagy through suppression of lysine 437 ubiquitination of Beclin 1 to inhibit Vps34 activity.

Results

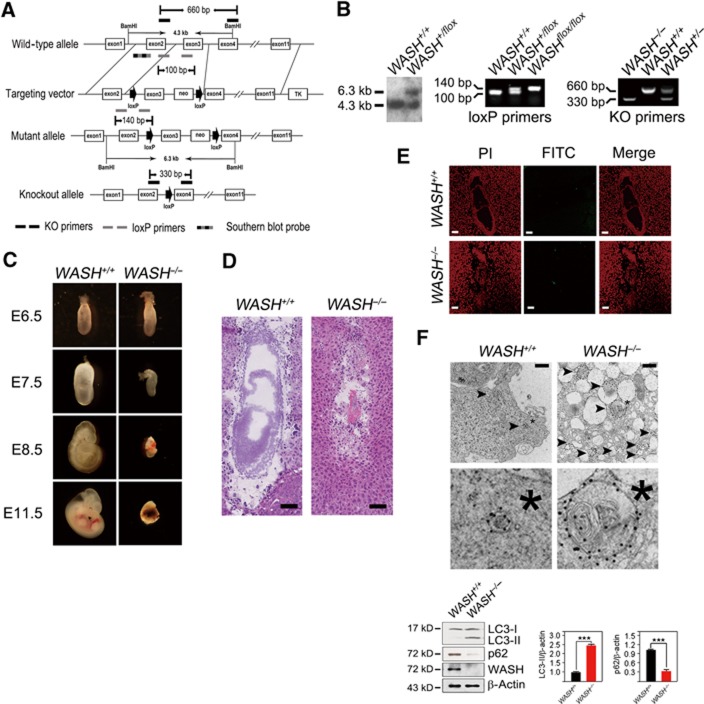

WASH deficiency causes embryonic lethality and extensive autophagy

To explore the in vivo roles of WASH, we generated WASH-conditional knockout (KO) mice (WASHflox/flox) with loxP sites flanking exon3 of the WASH gene (Figure 1A). WASH−/− mice were produced by crossing WASHflox/flox mice with Ella-Cre transgenic mice (Figure 1B). Surprisingly, no WASH−/− neonates were obtained from WASH+/−mice. Indeed, homozygous mutation of the WASH gene led to early embryonic lethality (Figure 1C). We observed that WASH was constitutively expressed in many tissues and various embryonic days of embryos (Supplementary Figure S1). We further found that WASH deficiency caused embryonic abnormality at embryonic day (E) 7.5 and the abnormal embryos were resorbed at E9.5. We found that E7.5 embryos of WASH−/− mice had no obvious three layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm) (Figure 1D). Some cavities, such as ectoplacental cavity, exocoelomic cavity, and amniotic cavity, were not well organized. Interestingly, the E7.5 WASH−/−embryonic cells exhibited massive cell death that was not apoptotic cell death (Figure 1E). Surprisingly, these embryos presented substantial autophagosome-like structures by electron microscopy (Figure 1F, upper panel). Moreover, we observed that light chain 3 (LC3) was localized in the autophagosome-like structures by immuno-electron microscopy. To confirm this autophagic phenotype, we isolated E7.5 embryos and lysed them for immunoblotting. Microtubule-associated LC3 is an autophagy indicator by conversion of LC3-I into LC3-II (Kabeya et al, 2000), and p62 is an autophagy substrate. We found that WASH−/− embryos exhibited dramatically enhanced LC3 conversion and a reduced level of p62 (Figure 1F, lower panel). WASH was deleted in the E7.5 WASH−/− embryo which was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-WASH antibody (Figure 1F, lower panel). We concluded that excessive autophagy caused by WASH deficiency leads to autophagic cell death of embryos, which is in agreement with autophagic cell death in previous reports (Yu et al, 2004; Elgendy et al, 2011). Collectively, WASH deficiency leads to early embryonic lethality and extensive autophagy of mouse embryos.

Figure 1.

WASH deficiency causes embryonic lethality and extensive autophagy. (A) Strategy to generate WASH-knockout (WASH−/−) mice. The coding exons of mWASH gene were shown as white boxes. The target vector with exon3 of mWASH gene was flanked with two loxP sites (arrow) and one neomycin resistance gene. The primers used for genotyping were KO primers for deficient genotypes, loxP primers for loxP site identification, and Southern blot probe for floxed mWASH gene. KO, knockout, m, mouse. (B) Detection of WASH gene targeting. The floxed WASH gene by gene targeting was analysed by Southern blotting (left panel) and PCR (middle panel). The genotypes of the offspring were analysed by PCR (right panel). (C) WASH deficiency is embryonic lethal. E11.5 of WASH deficiency showed a shrinked decidua. (D) Histological analysis of E7.5 WASH+/+ and WASH−/− embryos. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) WASH-deficient embryos do not undergo apoptosis. TUNEL assay was performed for apoptosis detection. PI, propidium iodide. FITC, fluoresceinisothiocyanate. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) E7.5 embryos of WASH−/− mice present extensive autophagy. Ultrastructure of isolated E7.5 embryos was stained with antibody against LC3 and visualized by immuno-electron microscopy. Black arrowhead indicates autophagosome. *, Cellular reference. Scale bar, 500 nm (upper panel). WASH+/+ or WASH−/− embryos were isolated, and LC3 conversion and p62 level were analysed by immunoblotting (lower panel). Bands were quantified and analysed by Image J and shown as means±s.d. ***P<0.001. Above experiments were repeated for three independent times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

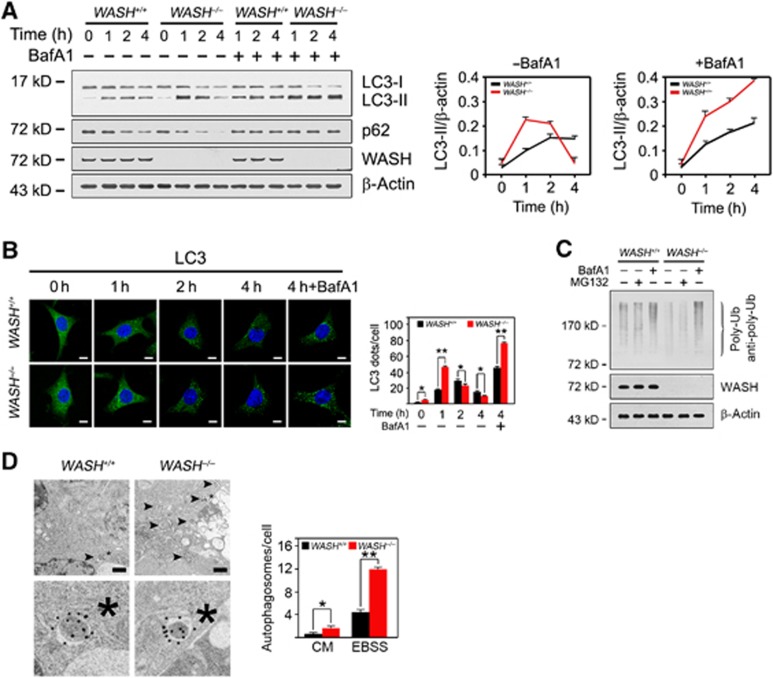

WASH inhibits autophagy

To examine how WASH regulates autophagy, we generated WASH−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) by expressing Cre recombinase in WASHflox/flox MEFs. WASH-deficient MEFs were treated with Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS), an amino acid and growth factor-free solution mimicking a nutrient-deprived condition. As expected, WASH deficiency enhanced much more conversion of LC3-I into LC3-II and degradation of p62 with nutrient deprivation compared with wild-type (WT) (WASH+/+) MEFs (Figure 2A). The autophagic process in WASH−/− MEFs took place more rapidly than that of WASH+/+ MEFs. Notably, a lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) was able to block the degradation of LC3-II and p62 during autophagy (Figure 2A), suggesting that WASH−/− MEFs induce robust autophagy and autophagic flux. Similar results were obtained by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 2B). Expectedly, WASH−/− MEFs showed a lower level of polyubiquitinated proteins (Figure 2C), and BafA1 could block the autophagic process but not a proteasome inhibitor MG132. Additionally, WASH−/− MEFs showed much more autophagosomes visualized by immuno-electron microscopy (Figure 2D). We observed that different morphologies between the WASH KO embryos and MEFs. The severe enlarged autophagosomes in WASH KO embryos might be caused by overactivated autophagy, which might not appear in cultured MEFs. Taken together, WASH deficiency enhances autophagy induction.

Figure 2.

WASH inhibits autophagy. (A) WASH deficiency enhances autophagy induction. WASH+/+ or WASH−/− MEFs were treated with EBSS for the indicated times in the presence or absence of 20 nM bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), and harvested for immunoblotting. Ratios of LC3-II/β-actin were calculated and shown at the right panel. (B) WASH knockout accelerates LC3 conversion by confocal microscopy. Endogenous LC3 puncta were visualized by staining with antibody against LC3 (left panel), and calculated as shown in the right panel. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Poly-ubiquitinated proteins are reduced in WASH−/− MEFs. WASH+/+ and WASH−/− MEFs were starved in EBSS for 2 h treated with or without 20 nM BafA1 or 10 μM MG132. Cells were harvested for immunoblotting with anti-poly-ubiquitin antibody (Enzo, clone FK1) that only recognizes poly-ubiquitinated ubiquitin chains. (D) Autophagosome-like structures in WASH+/+ and WASH−/− MEFs were visualized after starvation for 1 h by immuno-electron microscopy with antibody against LC3 (left panel). Black arrowhead indicates autophagosome. Scale bar, 500 nm. *, Cellular reference. Fifty cells were quantified from three independent experiments (right panel). Data were shown as means±s.d. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. Experiments were repeated for three independent times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

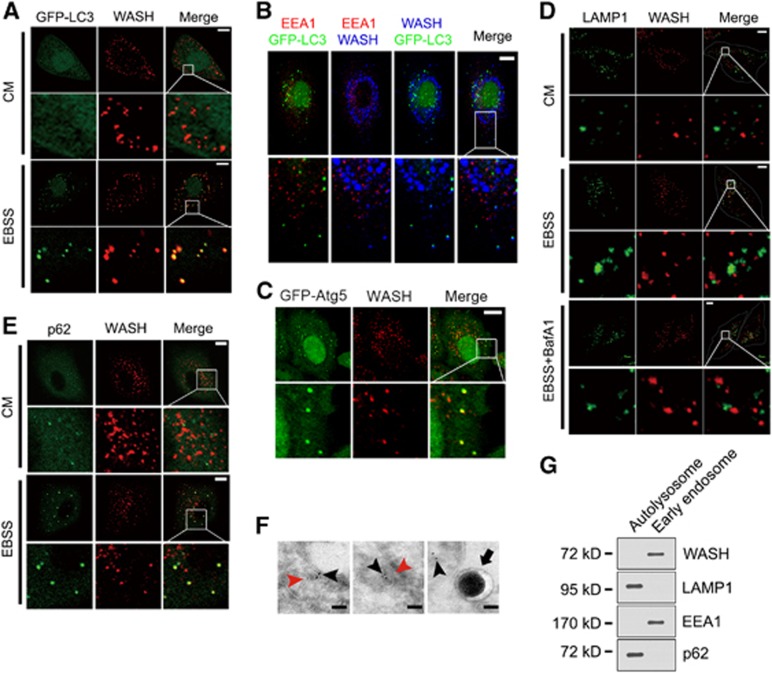

WASH is localized in autophagosomes

WASH was colocalized with GFP-LC3-positive autophagosomes under starvation (Figure 3A), but not under normal culture conditions (CM). This colocalization was not merged with EEA1 with EBSS treatment (Figure 3B), an early endosome marker, which colocalizes with WASH in CM culture, suggesting that WASH exerts its autophagic role independently of its endosomal trafficking function. p16-Arc is a component of the Arp2/3 complex that is essential for endosomal sorting and FAM21 is required for the endosomal localization of WASH (Singh et al, 2003; Gomez and Billadeau, 2009). p16-Arc or FAM21 silencing did not influence autophagy induction compared with the control shRNA-treated (shCtrl) cells (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). The VCA domain of WASH is required for the endosomal sorting function (Derivery et al, 2009; Jia et al, 2010). Additionally, the VCA domain-truncated WASH (ΔVCA) mutant could still rescue the accelerated autophagy induction in WASH KO MEFs comparable to that of the full-length (FL) WASH restoration (Supplementary Figure S2C). These observations indicate that WASH suppresses autophagy independently of its endosomal sorting function. Atg4 is essential for formation of autophagosomes, and Atg4 mutant (C74A) that impairs LC3 lipidation disrupts the closure of autophagosomes (Fujita et al, 2008). Importantly, in Atg4 (C74A)-expressed cells, WASH colocalized with Atg5 (Figure 3C), suggesting that WASH is localized in forming autophagosomes. However, WASH did not colocalize with the lysosome marker LAMP1 during the autophagy process (Figure 3D), which suggests that WASH does not function in autolysosomes. p62 is an autophagic substrate that is associated with LC3 on isolated membranes and incorporated into autophagosomes (Mathew et al, 2009; Itakura and Mizushima, 2011). Expectedly, WASH colocalized with p62 under starvation (Figure 3E). To further confirm the precise localization of WASH, we performed immuno-electron microscopy. We observed that WASH resided in the unclosed and closed autophagosomes, but not in the autolysosomes (Figure 3F). Moreover, WASH was not localized in the autolysosomes that was verified by detection of fractionation of organelles (Figure 3G). These results suggest that WASH may function in regulation of autophagosome formation.

Figure 3.

WASH is localized in autophagosomes. (A) WASH colocalizes with GFP-LC3 upon starvation. HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were stained with anti-WASH antibody after treatment with EBSS or culture medium (CM) for 1 h. (B) Autophagy-related WASH does not colocalize with EEA1. HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were cultured with EBSS for 1 h and stained with antibodies against EEA1 and WASH. (C) WASH localizes to unclosed autophagosomes. HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-Atg5 were transfected with Atg4B(C74A) mutant, followed by stimulation with EBSS for 1 h. Cells were stained with anti-WASH antibody (red). (D) WASH does not localize in autolysosomes. HeLa cells were treated with CM or EBSS in the presence or absence of 20 nM BafA1 at 37°C for 1 h. WASH and LAMP1 were visualized by staining with anti-WASH and anti-LAMP1 antibodies. (E) Colocalization of WASH and autophagy substrate p62 during autophagy. HeLa cells treated with or without EBSS were stained with anti-p62 and anti-WASH antibodies. For (A–E), scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Immuno-electron microscopy analysis of HeLa cells treated with EBSS for 1 h. Black arrowhead indicates WASH particle, red arrowhead indicates autophagosome, and black arrow denotes autolysosome. In all, 73±2% of autophagosomes contains WASH particles. Scale bar, 100 nm. (G) WASH is not localized in autolysosomes. Autolysosomes and early endosomes were separated from HeLa cells and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. The above experiments were repeated for three independent times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

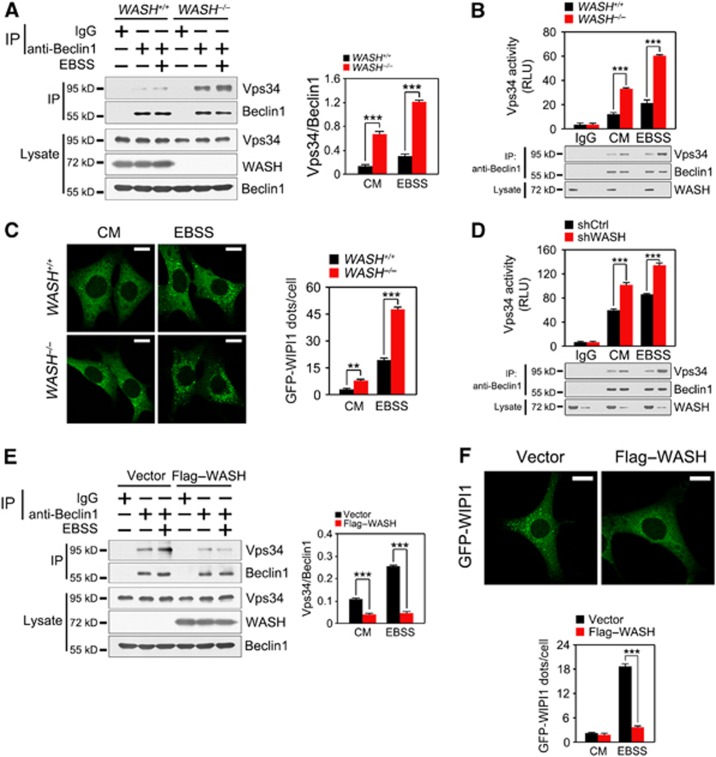

WASH suppresses Vps34 activity

We next wanted to test whether WASH inhibits autophagy through disturbing the Beclin 1–Vps34 complex. We found that anti-Beclin 1 antibody could precipitate much more Vps34 protein in WASH−/− MEFs than in WASH+/+MEFs, especially after EBSS treatment (Figure 4A). WASH deficiency did not change the stability of Beclin 1 even with EBSS treatment (Supplementary Figure S3). More importantly, WASH deficiency increased the Beclin 1-bound Vps34 kinase activity (Figure 4B). WIPI1 is a PI3P-binding protein that is involved in the formation of phagophores (Proikas-Cezanne et al, 2007). Notably, GFP-WIPI1 puncta were dramatically enhanced in WASH−/− MEFs in EBSS-induced autophagy (Figure 4C). Additionally, in WASH-silenced cells, Beclin 1 could precipitate more Vps34 protein compared with those of shCtrl cells. WASH depletion augmented Vps34 kinase activity (Figure 4D). By contrast, Flag–WASH-overexpressed MEFs declined the amount of co-purifying Vps34 protein level and dots of WIPI1 (Figure 4E and F). Collectively, WASH significantly inhibits Vps34 activity during the induction of autophagy.

Figure 4.

WASH inhibits Vps34 activity. (A) WASH deficiency enhances the interaction of Vps34 with Beclin 1. WASH+/+ and WASH−/− MEFs were treated with EBSS at 37°C for 1 h and immunoprecipitated for Beclin 1. IP, immunoprecipitation. Ratio of Vps34/Beclin 1 was calculated by the Image J software and shown in the right panel. (B) WASH KO MEFs were treated with or without EBSS at 37°C for 1 h followed by kinase assays. Cells were lysed and incubated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody to precipitate the autophagy-related Vps34. Immunoprecipitates were separated into two equal parts, one for kinase assays and the other for input detection. RLU, relative light unit. (C) WASH deficiency enhances Vps34 activity. WASH+/+ and WASH−/− MEFs stably expressing GFP-WIPI1 were stimulated with or without EBSS for 1 h followed by confocal microscopy (left panel). GFP-WIPI1 dots were calculated and shown in the right panel. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) WASH-silenced HeLa cells were treated with or without EBSS at 37°C for 1 h, and detected as above. (E) WASH attenuates the interaction of Beclin 1 with Vps34. MEFs stably expressing vector or Flag–WASH were starved with EBSS for 1 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Beclin 1 antibody. Ratio of Vps34/Beclin 1 was shown in the right panel. (F) WASH overexpression reduces Vps34 activity. MEFs stably expressing GFP-WIPI1 were transfected with vector or Flag–WASH and then starved with EBSS for 1 h, followed by visualization with confocal microscopy (upper panel). GFP-WIPI1 dots were calculated and shown in the lower panel. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are shown as means±s.d. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Experiments were repeated for three independent times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

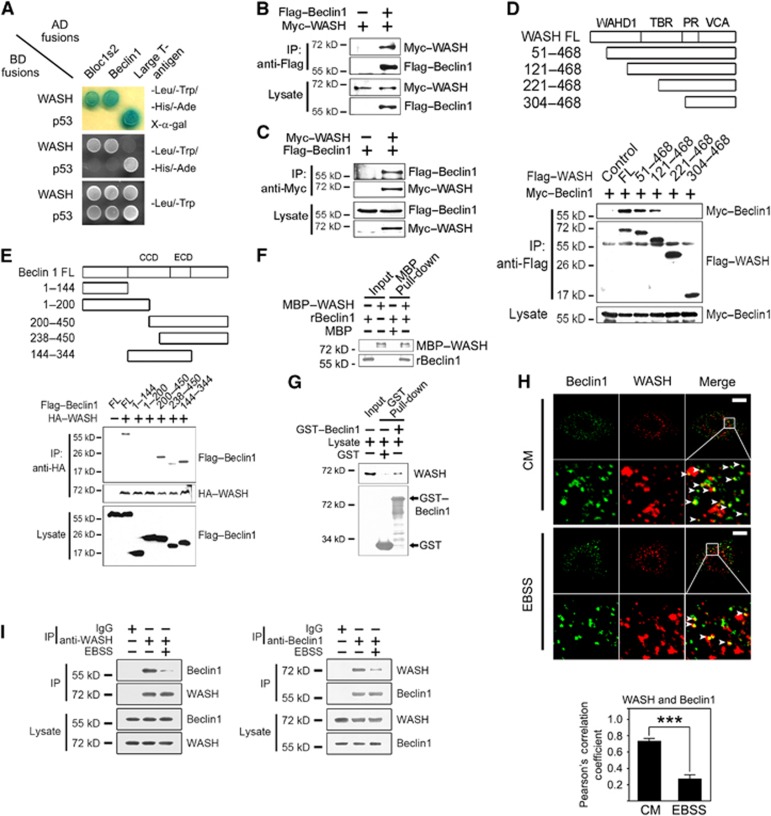

WASH interacts with Beclin 1

We screened a human spleen cDNA library to fish out WASH interactors using a yeast two-hybrid approach. Beclin 1 is a core component of Vps34 complex (Kihara et al, 2001; Funderburk et al, 2010). Interestingly, we identified that WASH was a novel interacting protein of Beclin 1 (Figure 5A). Bloc1s2, a known interactor of WASH (Monfregola et al, 2010), was used as a positive control in verification of the association via the yeast two-hybrid assay. Additionally, WASH did not interact with other components of the Vps34 or the Ulk1/Ulk2 complex (Supplementary Figure S4). The WASH–Beclin 1 interaction was verified in co-transfected human embryonic kidney epithelial 293T (HEK293T) cells by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) (Figure 5B and C). Using truncated WASH fragments, we defined that WASH (aa121–221) was necessary and sufficient for interaction with Beclin 1 (Figure 5D). Importantly, the deletion of aa121–221 (Δ121–221) of WASH failed to restore the accelerated autophagy process in WASH KO MEFs (Supplementary Figure S5A). However, the deletion of aa121–221 (Δ121–221) of WASH was able to rescue the enhanced EGFR degradation in WASH KO MEFs, while the WASH (ΔVCA) mutant had no such activity (Supplementary Figure S5B). These data confirmed that WASH exerts its autophagy regulation independently of its endosomal sorting role. Additionally, the central region of Beclin 1 (aa200–238) was mainly sufficient for association with WASH (Figure 5E). Moreover, recombinant MBP-tagged WASH (MBP–WASH) was able to pull down recombinant Beclin 1 (rBeclin 1) (Figure 5F), indicating that WASH directly binds to Beclin 1. Moreover, GST–Beclin 1 or anti-Beclin 1 antibody could precipitate endogenous WASH and vice versa (Figure 5G). We observed that the colocalization rate between WASH and Beclin 1 was declined under nutrient-deprived conditions compared with CM conditions by confocal microscopy (Figure 5H), indicating that reduced WASH binding appeared undergoing autophagy. Additionally, with EBSS treatment, the decreased association between WASH and Beclin 1 was confirmed by co-IP assays (Figure 5I).

Figure 5.

WASH associates with Beclin 1. (A) The interaction of WASH with Beclin 1 was validated by yeast two-hybrid assays. Yeast strain AH109 was co-transfected with Gal4 DNA-binding domain (BD) fused WASH and Gal4 activating domain (AD) fused Beclin 1. p53 and large T antigen or a known WASH interactor Bloc1s2 was introduced as positive controls. (B, C) WASH co-immunoprecipitates Beclin 1 in mammalian cells. Flag-tagged Beclin 1 and Myc-tagged WASH were co-transfected into HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitations were performed at 24 h post transfection. IP, immunoprecipitation. (D) Mapping the interacting regions between WASH and Beclin 1. (E) The indicated Flag-tagged Beclin 1 constructs encoding different regions of Beclin 1 were co-transfected with full-length HA-tagged WASH (HA–WASH) into HEK293T cells followed by immunoprecipitation. (F) WASH directly interacts with Beclin 1. Recombinant MBP-tagged WASH (MBP–WASH) or Beclin 1 (rBeclin 1) was expressed in E. coli and then subjected to MBP pull-down assay. (G) GST–Beclin 1 precipitates WASH from HeLa cell lysates. GST-Beclin 1 or GST was bound to GST beads and incubated with HeLa cell lysates followed by immunoblotting. (H) Endogenous WASH colocalizes with Beclin 1 via confocal microscopy. HeLa cells cultured in CM or EBSS for 1 h were stained with antibodies against Beclin 1 and WASH. The colocalization rate (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) between Beclin 1 and WASH was calculated and shown as means±s.d. in the lower panel. Scale bar, 10 μm. (I) HeLa cells were treated with CM or EBSS for 1 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with antibodies against WASH (left panel) or Beclin 1 (right panel), and the immunoprecipitates were detected with the indicated antibodies.***P<0.001. All the above experiments were repeated for at least three times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

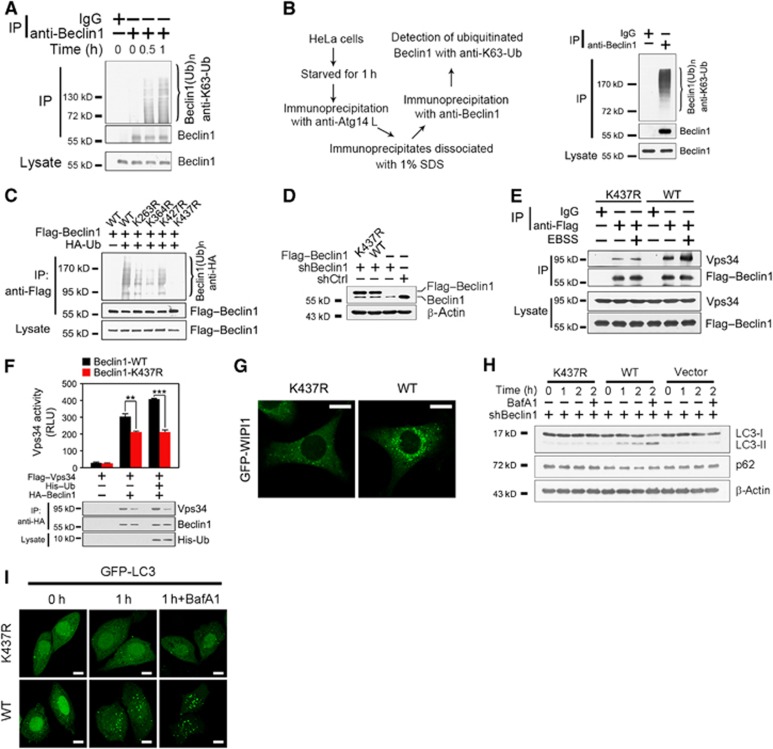

Lysine 437 ubiquitination of Beclin 1 is required for autophagy induction

To test whether Beclin 1 is ubiquitinated undergoing starvation-induced autophagy, we treated HeLa cells with EBSS to detect poly-ubiquitination of Beclin 1. We found that Beclin 1 was ubiquitinated during the process of autophagy (Figure 6A; Supplementary Figure S6), the ubiquitination of Beclin 1 was through lysine 63 (K63) linkage, but not through K48 linkage (data not shown). To further verify the ubiquitination state of Beclin 1, we first performed immunoprecipitation with anti-Atg14L antibody, and then did re-immunoprecipitation with anti-Beclin 1 antibody to separate autophagy-related Beclin 1 (Figure 6B, left panel). We found that the autophagic Beclin 1 was really poly-ubiquitinated and this ubiquitination was K63 linked (Figure 6B, right panel). To identify the ubiquitination site on Beclin 1, we mutated all the indicated lysines to arginines (Figure 6C; Supplementary Figure S6), which were evolutionarily conserved from yeast to humans. We defined that the ubiquitination site of Beclin 1 was at lysine 437 (Figure 6C). A recent report showed that Beclin 1 can be ubiquitinated in TLR4-induced autophagy in macrophages (Shi and Kehrl, 2010). They found that Beclin 1 is ubiquitinated at Lys117. However, we found that K117R-Beclin 1 mutant expressed in Beclin 1-silenced HeLa cells could still be ubiquitinated under EBSS treatment (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 6.

Lysine 437 ubiquitination of Beclin 1 is required for autophagy induction. (A) Endogenous Beclin 1 is ubiquitinated through K63 linkage during the process of autophagy. HeLa cells starved in EBSS for the indicated times were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were dissociated with 1% SDS and re-immunoprecipitated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with antibody specific for lysine 63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains (anti-K63-Ub). (B) The autophagy-specific Beclin 1 is ubiquitinated through K63 linkage. After starved in EBSS for 1 h, HeLa cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Atg14L antibody before dissociated with 1% SDS. Immunoprecipitates were further precipitated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-K63-Ub antibody. The left panel denotes the scheme for separation of autophagy-specific Beclin 1. The right panel indicates ubiquitination state of autophagy-specific Beclin 1. (C) Lysine 437 mutation to arginine (K437R) abrogates ubiquitination of Beclin 1. Different constructs of Flag-tagged Beclin 1 mutants were co-transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA–Ub) into HEK293T cells. (D) Beclin 1 (WT) or K437R-Beclin 1 (K437R) mutant was stably expressed in Beclin 1-silenced HeLa cells. Beclin 1-knockdown HeLa cells were infected with lentivirus encoding 3XFlag-tagged WT Beclin 1 (WT) or K437R-Beclin 1 (K437R). (E) K437R-Beclin 1 mutant abrogates the enhanced interaction of Beclin 1 with Vps34 during autophagy. HeLa cells expressing 3XFlag–Beclin 1 or 3XFlag–K437R-Beclin 1 were treated with EBSS for 1 h, and harvested for immunoprecipitation. (F) Vps34 kinase activity is impaired by K437R-Beclin 1 mutant. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated vectors for 24 h and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody followed by a Vps34 kinase assay. Immunoprecipitates were separated into two equal parts, one for kinase assays and the other for input detection. (G) K437R-Beclin 1 reduces the activation of Vps34. Beclin 1-silenced HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-WIPI1 were rescued with WT- or K437R-Beclin 1, followed by stimulation with EBSS for 1 h. GFP-WIPI1 dots were visualized by confocal microscopy. (H) K437R-Beclin 1 mutant fails to induce autophagy after starvation. Beclin 1-knockdown HeLa cells expressing WT or K437R mutant of Beclin 1 (K437R) were starved with EBSS for the indicated times. (I) K437R-Beclin 1 mutant suppresses autophagosome formation. Beclin 1-knockdown HeLa cells expressing WT-Beclin 1 or K437R-Beclin 1 were infected with lentivirus encoding GFP-LC3, and stimulated with EBSS for 1 h in the presence or absence of 20 nM BafA1. GFP-LC3 dots were visualized by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are shown as means±s.d. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. All the above experiments were repeated for at least three times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

We generated cells stably expressing WT- or K437R-Beclin 1 in Beclin 1-silenced HeLa cells (Figure 6D). The expression levels of WT- and K437R-Beclin 1 were similar to that of endogenous Beclin 1. WT-Beclin 1 could precipitate much more Vps34 compared with K437R-Beclin 1 mutant, especially under starved conditions (Figure 6E), suggesting that K437 ubiquitination is required for starvation-induced autophagy. Furthermore, K437R-Beclin 1 mutant attenuated the Beclin 1-associated Vps34 kinase activity (Figure 6F), which was verified by GFP-WIPI1 punctate formation (Figure 6G). K437R-Beclin 1-rescued HeLa cells failed to convert LC3 and degrade p62 with EBSS treatment (Figure 6H), which was further verified by GFP-LC3 punctate patterns (Figure 6I). Collectively, K437 ubiquitination of Beclin 1 is required for autophagy induction.

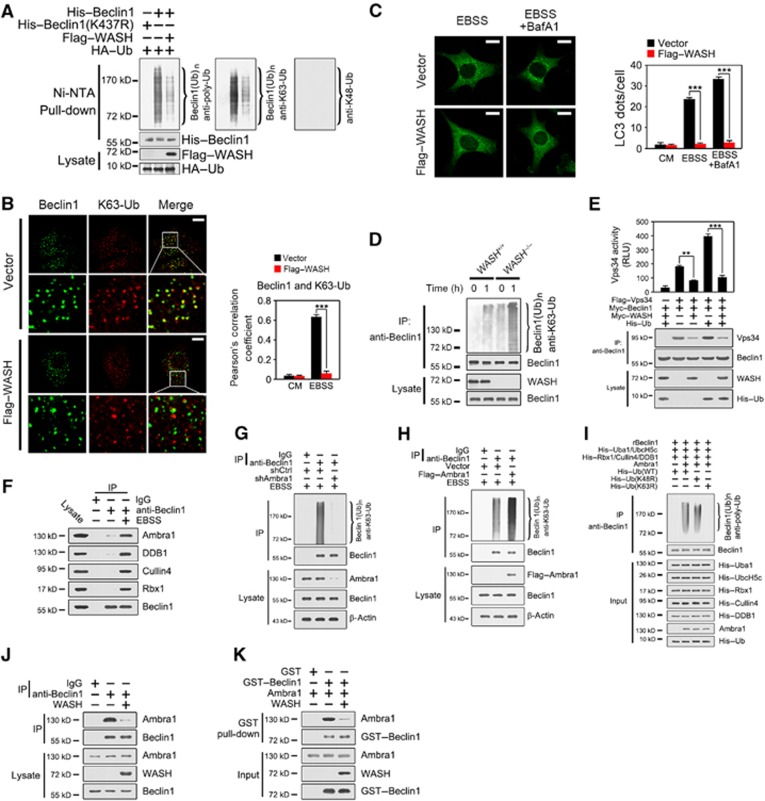

WASH suppresses Beclin 1 ubiquitination to inactivate Vps34 activity

Interestingly, Flag–WASH overexpression dramatically reduced the ubiquitination level of Beclin 1, which was K63-linked, but not K48-linked ubiquitination (Figure 7A). Consistently, K437 mutation abolished the ubiquitination of Beclin 1. We stained Beclin 1 and K63-Ub in Flag–WASH or vector-transfected HeLa cells followed by confocal microscopy. We found that the colocalization between Beclin 1 and K63-Ub was remarkably declined in WASH-overexpressed HeLa cells with EBSS treatment (Figure 7B). Importantly, WASH overexpression significantly suppressed LC3 lipidation after EBSS treatment (Figure 7C). Additionally, we found that WASH KO MEFs showed much more poly-ubiquitinated Beclin 1 compared with WT MEFs after starvation (Figure 7D), which is K63 linked, but not K48 linked (data not shown). Moreover, ubiquitinated Beclin 1 dramatically elevated Vps34 kinase activity, whereas WASH overexpression significantly decreased the Vps34 activity (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

WASH suppresses the ubiquitination of Beclin 1 to inactivate Vps34 activity. (A) WASH overexpression suppresses the ubiquitination of Beclin 1. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated vectors for 24 h followed by an Ni-NTA-based pull-down assay and immunoblotted with anti-poly-ubiquitin (anti-poly-Ub) (left panel), and anti-K63-specific ubiquitin (anti-K63-Ub) (middle panel) antibodies. The same blot was stripped and probed with anti-K48-specific ubiquitin (anti-K48-Ub) antibody (right panel). (B) WASH overexpression hinders K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1. HeLa cells stably expressing vector or Flag–WASH were treated with CM or EBSS with or without BafA1 for 1 h and then stained with antibodies against endogenous Beclin 1 and K63-linked polyubiquitin (K63-Ub). The colocalization rate (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) between Beclin 1 and K63-Ub was calculated and shown in the right panel. (C) WASH overexpression inhibits LC3 lipidation. HeLa cells stably expressing vector or Flag–WASH were treated with CM or EBSS with or without BafA1 for 1 h and then stained with antibody against endogenous LC3. LC3 dots were calculated and shown in the right panel. (D) WASH deficiency increases K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1. WASH+/+ and WASH−/− MEFs were treated with EBSS at 37°C for 1 h and lysed for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Beclin 1 antibody and probed with antibody against K63-linked poly-ubiquitin. (E) WASH overexpression inhibits Vps34 activity. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated vectors and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Beclin 1 antibody for Vps34 kinase activity assay. Immunoprecipitates were separated into two equal parts, one for kinase assay and the other for input detection. RLU, relative light unit. (F) Beclin 1 associates Ambra1 upon autophagy induction. HeLa cells treated with EBSS for 1 h were lysed for immunoprecipitation with anti-Beclin 1 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (G) Ambra1 knockdown declines Beclin 1 ubiquitination. HeLa cells with Ambra1 knockdown were treated with EBSS for 1 h, followed by immunoprecipitated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were dissociated with 1% SDS and re-immunoprecipitated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (H) Ambra1 overexpression increases Beclin 1 ubiquitination. HeLa cells with Ambra1 overexpression were treated as above. (I) Ambra1 can directly ubiquitinate Beclin 1 by an in vitro ubiquitination assay. Recombinant Beclin 1 (rBeclin 1) and components of the ubiquitination system were expressed and purified as described in Materials and methods. The reaction started by mixing the indicated components in ubiquitination buffer at 37°C for 1 h and followed by immunoblotting. (J, K) WASH and Ambra1 competitively bind to Beclin 1. HeLa cells with vector or WASH overexpression were starved for 1 h and lysed for immunoprecipitation with anti-Beclin 1 antibody (J). Recombinant Ambra1 and WASH proteins were incubated with GST–Beclin 1, followed by GST pull-down assays (K). Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are shown as means±s.d. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Data were repeated for at least three times with similar results.

Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

To further identify the E3 ligase of Beclin 1, we used anti-Beclin 1 antibody to pull down candidates from the EBSS-treated lysates. Interestingly, we found that Beclin 1 could precipitate Ambra1 (Figure 7F), as well as DDB1, Cullin 4, and Rbx1, which are the components of the DDB1–Cullin 4 complex (Jin et al, 2006; Braun et al, 2011; Fischer et al, 2011). Ambra1 was reported as a candidate substrate receptor for the DDB1–Cullin 4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Jin et al, 2006). Importantly, knockdown of Ambra1 dramatically declined ubiquitination of Beclin 1 under EBSS treatment (Figure 7G). In contrast, Flag–Ambra1 overexpression remarkably enhanced Beclin 1 ubiquitination (Figure 7H). To further verify that the Ambra1 is an E3 ligase for K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1, we performed an in vitro ubiquitination reconstitution assay. Expectedly, Ambra1 could directly ubiquitinate Beclin 1 in the in vitro ubiquitination reconstitution system (Figure 7I). Importantly, Beclin 1 could be polyubiquitinated by WT and K48-mutated ubiquitin (K48R), but not by K63-mutated ubiquitin (K63R), suggesting that Ambra1 contributes to the K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1. TRAF6 and NEDD4 were reported to be the two E3 ligases for Beclin 1 ubiquitination that regulates the Vps34 activity (Shi and Kehrl, 2010; Platta et al, 2012). We observed that knockdown of NEDD4 or TRAF6 failed to affect the Beclin 1 ubiquitination under EBSS treatment (Supplementary Figure S8). Thus, these observations indicate that Ambra1 is an E3 ligase for K63-linked Beclin 1 ubiquitination in starvation-induced autophagy. More importantly, WASH overexpression dramatically reduced the association between Beclin 1 and Ambra1 (Figure 7J), which was verified by in vitro incubation of recombinant proteins (Figure 7K). These data indicate that WASH and Ambra1 can competitively bind Beclin 1, and WASH suppresses the Beclin 1 ubiquitination through the competitive binding inhibition.

Discussion

Herein, we showed that WASH negatively regulates autophagy through suppression of Beclin 1 polyubiquitination. K437 ubiquitination of Beclin 1 is required for autophagy induction. Our data suggest that, for autophagy induction, Beclin 1 is rapidly ubiquitinated at K437 via K63 linkage, and then ubiquitinated Beclin 1 binds to Vps34 to augment Vps34 activity. For autophagy suppression, WASH binds to Beclin 1 to impede its ubiquitination. Thus, non-ubiquitinated Beclin 1 fails to associate with Vps34 to inactivate its kinase activity, leading to autophagy suppression.

During embryo development, cells take various processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and cell death, rendering the embryo to transform into an adult organism. Loss-of-function studies demonstrated that autophagy played a crucial role in embryogenesis. Here, we found that WASH was expressed in early embryonic stages and WASH deficiency caused extensive embryonic autophagy. Actually, we did a rescue experiment by crossing WASH+/−Atg5+/− mice with WASH+/−Atg5+/− mice. WASH−/−Atg5−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian frequency, and they appeared almost normal at birth and died 1 day of delivery. In this case, WASH deficiency did not rescue the Atg5 KO phenotype, but Atg5 deletion could rescue the WASH KO phenotype. These data indicate that Atg5 deficiency could inhibit WASH-mediated excessive autophagy, which implies that WASH is an upstream regulator in Atg5-mediated autophagy. The suppression of autophagy by Atg5 deficiency could partially rescue the lethal phenotype of WASH KO embryos, suggesting that excessive autophagy might be a main cause to WASH KO embryonic lethality at E7.5. Whether other defects may account for the embryonic lethality needs to be further investigated. WASH deficiency also caused embryonic lethality of Drosophila, suggesting that autophagy homeostasis in development might be highly evolutionarily conserved.

WASH generates directed actin filaments to aid fission of the budding vesicles via Arp2/3 activation (Derivery et al, 2009; Gomez and Billadeau, 2009). WASH is a major nucleation-promoting factor (NPF) and asymmetric distribution on endosomes. We show that WASH in autophagosomes undergoing autophagy is not localized in the endosomes (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the Beclin 1-associated WASH was not in the FAM21-containtaing WASH complex. Moreover, WASH KO MEFs did not affect endosomal trafficking. p16-Arc is a component of Arp2/3 complex (Singh et al, 2003), whose depletion did not influence autophagy induction. Our findings indicate that the autophagy-associated WASH is not involved in the endosomal trafficking.

Similarly to its orthologue in yeast, Vps34 in mammalian cells exists in two complexes, in which Beclin 1, Vps34, and p150/Vps15 are the core components (Zeng et al, 2006; Funderburk et al, 2010). The Vps34 complexes are finely controlled by each component. UVRAG (UV irradiation resistance-associated gene) can activate the Beclin 1–Vps34 complex when cells encounter nutrient limitation (Liang et al, 2006; Itakura et al, 2008). Atg14L (yeast Atg14-like) augments Vps34 kinase activity and enhances autophagy (Itakura et al, 2008; Matsunaga et al, 2009; Zhong et al, 2009). Notably, Rubicon (RUN domain and cysteine-rich domain containing, Beclin 1-interacting protein) is assembled in the Beclin 1–Vps34 complex (Itakura et al, 2008; Matsunaga et al, 2009; Zhong et al, 2009), which inhibits autophagy through disturbing autophagosome maturation. Interestingly, we demonstrate that WASH associates with Beclin 1 and is present in the Atg14L–Beclin 1–Vps34 complex, suggesting that WASH might function in the early stage of autophagosome biosynthesis.

Phosphorylation of Beclin 1 by several kinases liberates Beclin 1 from its binding partners of Bcl-2 family to induce autophagy (Zalckvar et al, 2009). Vps34 can be phosphorylated by Cdk1 that disrupts the Beclin 1–Vps34 complex (Furuya et al, 2010), negatively regulating autophagy during mitosis. A recent report showed that Beclin 1 can be ubiquitinated by an E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 in TLR4-induced autophagy in macrophages. They found that the K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1 is at K117 of the BH3 domain during TLR4-triggered autophagy in macrophages. However, we found that the K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1 is at K437 of C-terminus under a nutrient-deprived condition in HeLa cells. We identified that Ambra1 is an E3 ligase for K63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin 1 in starvation-induced autophagy. Ambra1, also called as DCAF3, is interacted with the DDB1–Cullin 4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Jin et al, 2006; Fischer et al, 2011). DCAF substrate receptors confer the E3 substrate specificity (Wertz et al, 2004; Bennett et al, 2010; Fischer et al, 2011). Ambra1 is the substrate receptor for ubiquitination of Beclin 1 in starvation-induced autophagy. However, whether different autophagic stimuli cause distinct lysine ubiquitination of Beclin 1 or distinct lysine ubiquitination in different cell types via different ubiquitin ligases needs to be further investigated.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

A rabbit polyclonal antibody against WASH was raised from the VCA domain of WASH protein. The VCA domain was subcloned into pGEX6P-1 vector, and purified with a GST-sepharose (GE Healthcare) column, followed by treatment of PreScission protease to remove the GST tag. The anti-WASH antibody specifically recognized both mouse and human WASH in recombinant or endogenous forms. Commercial antibodies rabbit polyclonal antibodies anti-LC3, anti-Beclin 1, anti-Atg14L, anti-Ambra1, anti-DDB1, anti-Cullin 4, anti-Rbx1, anti-TRAF6, anti-NEDD4, anti-EGFR, anti-p16-Arc, and anti-Vps34 were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-poly-ubiquitin antibody (clone FK1) was from Enzo. Mouse monoclonal antibodies anti-β-actin and anti-Flag were from Sigma-Aldrich. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies anti-LC3 and anti-p62 were from MBL. Anti-HA, anti-EEA1, anti-Myc, and anti-FAM21 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa-488, Alexa-594, or Alexa-405 were purchased from Molecular Probes. Donkey anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa-488 or Alexa-594 were from Molecular Probes. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz. BafA1 and MG132 were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture

HEK293T, HEK293A, and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), β-mercaptoethanol, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin. MEFs were obtained from E14.5 embryos, and supplied with DMEM containing 20% FBS. EBSS was used as starvation culture for the indicated time points.

Generation of WASH −/− mice

The target vector of WASH-conditional KO mice (WASHflox/flox) was constructed to flank exon3 of mouse WASH gene with two loxP sites as described previously (Li et al, 2011). The vector was transfected into embryonic stem (ES) cells of 129 mice. After neomycin selection, the ES clones flanking loxP sites were microinjected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice. WASH+/flox mice were obtained after several rounds of selection. WASHflox/flox mice were generated via intercrossing of WASH+/flox mice. WASH+/− mice were produced by crossing WASHflox/flox mice with EIIa-Cre transgenic mice. WASH−/− mice were generated by intercrossing of WASH+/− mice.

Generation of WASH −/− MEFs

MEFs were prepared from E14.5 WASHflox/flox embryos and infected with the lentivirus encoding the Cre recombinase for 48 h. MEF cells were further selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin to generate WASH-deficient cells. WASH expression was confirmed by western blotting and immunostaining. WASHflox/flox MEFs were infected with lentivirus encoding the indicated GFP fusion proteins with or without Cre recombinase flanked by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Forty-eight hours after infection, MEFs were analysed by flow cytometry, and GFP-positive cells were collected for subsequent experiments.

Yeast two-hybrid screening

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed using a MatchmakerTM Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid system (Clontech/Takara) under the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, WASH was subcloned into pGBKT7 vector (BD-WASH). Yeast AH109 cells were transfected with BD-WASH and plasmids containing a human spleen cDNA library (Clontech/Takara) and then plated on SD medium lacking adenine, histidine, tryptophan and leucine. Selected clones were isolated and identified by DNA sequencing. Recovery of the plasmids and β-gal assay were carried out as described previously (Zhao et al, 2007). Bloc1s2 was subcloned into pGADT7 vector (AD-Bloc1s2) and co-transfected with BD-WASH, whose interaction served as a positive control.

Vps34 kinase assay

Endogenous Vps34 or overexpressed Flag–Vps34 was immunoprecipitated by antibody against Beclin 1. Immunoprecipitated beads were washed for three times and added with sonicated phosphatidylinositol (Sigma) (1 μl of 5 mg) and (1 μl of 10 mM) ATP in 30 μl reaction buffer (40 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml BSA) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The conversion of ATP into ADP level was measured by an ADP-GloTM Kinase Assay Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro ubiquitination reconstitution assay

Uba1, UbcH5c, Rbx1, ubiquitin, and Cullin 4 were subcloned into pET-28a vectors. Ambra1 was subcloned into pMAL-c2p vector. Beclin 1 was subcloned into pGEX-6p-1 vector. Plasmids were then transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). DE3 clones were cultured (OD600=0.6) and then induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16°C for 24 h. Cells were collected and lysed and further purified by Ni-NTA resin columns, MBP columns (Novagen) or GST-sepharose columns (GE Healthcare). His-DDB1 was expressed in Sf9 cells using a baculovirus expression system and purified by an Ni-NTA column. The in vitro ubiquitination reconstitution assay was performed by mixing E1 (Uba1), E2 (UbcH5c), E3 (Ambra1, DDB1, Cullin 4, and Rbx1), ubiquitin and Beclin 1 (after cleaving GST tag by Precision digestion) in the ubiquitination buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 mM ATP, pH 7.4) of 30 μl volume at 37°C for 1 h.

Immunofluorescence assay

MEFs or HeLa cells were grown on 0.01% poly-L-lysine-treated coverslips and transfected with the indicated vectors by Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) for 24 h as described previously (Fan et al, 2003). After starvation stimulation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at RT followed by permeabilization with 50 μg/ml digitonin for 20 min at RT. Ten percent of donkey serum was used for blocking and primary antibodies were added for 2 h at RT. After washing with PBS, the coverslips were stained with Alexa488-, Alexa594- or Alexa405-conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were obtained with laser scanning confocal microscopy (Olympus FV500).

Separation of autolysosomes and early endosomes

Autolysosomes and early endosomes were separated as previously described (Tjelle et al, 1996; Yu et al, 2010) and analysed by immunoblotting.

Electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), HeLa cells or MEFs were harvested by trypsin digestion and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde on ice for 2 h followed by postfixation in 2% osmium tetroxide (Zhao et al, 2007). Briefly, cells were immersed in SPI-PON812 resin after dehydrating with sequential washes in 50, 70, 90, 95, and 100% ethanol. The ultrathin sections were collected on copper grids and counterstained using uranyl acetate and lead citrate. For mouse embryo electron microscopy, E7.5 embryos were prepared and treated the same as above. For immuno-EM, HeLa cells or MEFs were starved for 1 h, fixed with 4% PFA and 0.05% glutaraldehyde for 2 h on ice and then cryo-sectioned by a Tokuyasu method and mounted in copper grids followed by blocking in 1% BSA. The sections were stained with anti-WASH (30 ng/μl) antibody and further stained with 10 nM gold-linked anti-rabbit IgG. Next, they were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and stained with neutral uranyl acetate before coating with 2% methyl cellulose. Images were taken with an FEI Tecnai spirit transmission electron microscope.

RNA interference

RNA interference sequences were designed according to pSUPER system instructions (Oligoengine). HeLa cells were transfected with pSUPER vector encoding target sequence against Beclin 1 (#1 5′-TCAGGAGAGGAGCCATTTA-3′, #2 5′-TGGACAGTTTGGCACAATC-3′), WASH (#1 5′-GTCGGATCTCTTCAACAAG-3′, #2 5′-GGCCAAGATTGAGAAGATC-3′), Ambra1 (#1 5′-CCCAGAAAAGAATGCTGTC-3′, #2 5′-AGGGCAAGAGAGTAGAACT-3′), p16-Arc (#1 5′-GGTGGACGTGGATGAATAT-3′, #2 5′-CAGGCAGCATTGTCTTGAA-3′), FAM21 (#1 5′-GGCCTACTACAGTTTCTAC-3′, #2 5′-CAGTGAAGAAGGCTCTGTA-3′), NEDD4 (#1 5′-CCAAGATTGGAGAGACCAT-3′, #2 5′-ACCTAAAACCAGTGGCTCA-3′), TRAF6 (#1 5′-CTGAAAGTGACTGCTGTGT-3′, #2 5′-CCTGTAGCGCTGTAACAAA-3′), or scramble sequences. Forty-eight hours after transfection, stably silenced clones were selected by 1 μg/ml puromycin.

Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated vectors for 24 h. Cells were harvested and treated with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–Cl, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.4). Supernatants were achieved by centrifugation (15 000 g, 15 min, 4°C), and incubated with the indicated antibodies for 6 h at 4°C followed by immunoprecipitation with 30 μl protein A/G agarose. The precipitates were completely washed with PBS and tested by immunoblotting. For poly-ubiquitinated Beclin 1 assay, immunoprecipitates were denatured by boiling with 1% SDS and re-immunoprecipitated with anti-Beclin 1 antibody.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used as statistical analysis by using Microsoft Excel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Timothy Gomez and Daniel Billadeau for the antibody against human WASH and plasmid for shWASH. We thank Dr Alexis Gautreau for antibody against mouse WASH. We thank Dr Yulong He for providing Adenovirus-GFP-Cre vector. We thank Drs Tamotsu Yoshimori and Li Yu for helpful advice. We thank Xuan Yang and Dr Yong Gong for protein expression and Yan Teng for technical support. We also thank Drs Liang Tong, Dangsheng Li, and Geng Zhang for critical reading and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30830030, 30972676, and 31100971), 973 Program of the MOST of China (2010CB911902), the Strategic Priority Research Programs of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01010407 and XDA01010103), the National Key Project of Scientific and Technical Supporting Programs of the MOST of China (2006BAI23B02), and the Chinese National Key Program on Basic Research (2012CB945103).

Author contributions: PX and SW designed and performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper; ZZ and ZD performed experiments; YD and LS designed constructs for conditional knockout mice; LS performed electron microscopy; GH expressed proteins in a ubiquitination system; BY and CL analysed the data; NH, XC, and XY generated conditional knockout mice; QS performed mouse experiments, LL. analysed the data; Z.F. initiated the study, organized, designed, and wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bennett EJ, Rush J, Gygi SP, Harper JW (2010) Dynamics of Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase network revealed by systematic quantitative proteomics. Cell 143: 951–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodemann BO, Orvedahl A, Cheng TL, Ram RR, Ou YH, Formstecher E, Maiti M, Hazelett CC, Wauson EM, Balakireva M, Camonis JH, Yeaman C, Levine B, White MA (2011) RalB and the exocyst mediate the cellular starvation response by direct activation of autophagosome assembly. Cell 144: 253–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun S, Garcia JF, Rowley M, Rougemaille M, Shankar S, Madhani HD (2011) The Cul4-Ddb1(Cdt2) ubiquitin ligase inhibits invasion of a boundary-associated antisilencing factor into heterochromatin. Cell 144: 41–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivery E, Sousa C, Gautier JJ, Lombard B, Loew D, Gautreau A (2009) The Arp2/3 activator WASH controls the fission of endosomes through a large multiprotein complex. Dev Cell 17: 712–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R, Asara JM, Fitzpatrick J, Dillin A, Viollet B, Kundu M, Hansen M, Shaw RJ (2011) Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science 331: 456–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgendy M, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Martin SJ (2011) Oncogenic Ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol Cell 42: 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan ZS, Beresford PJ, Oh DY, Zhang D, Lieberman J (2003) Tumor suppressor NM23-H1 is a granzyme A-activated DNase during CTL-mediated apoptosis, and the nucleosome assembly protein SET is its inhibitor. Cell 112: 659–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimia GM, Stoykova A, Romagnoli A, Giunta L, Di Bartolomeo S, Nardacci R, Corazzari M, Fuoco C, Ucar A, Schwartz P, Gruss P, Piacentini M, Chowdhury K, Cecconi F (2007) Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature 447: 1121–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer ES, Scrima A, Bohm K, Matsumoto S, Lingaraju GM, Faty M, Yasuda T, Cavadini S, Wakasugi M, Hanaoka F, Iwai S, Gut H, Sugasawa K, Thoma NH (2011) The molecular basis of CRL4(DDB2/CSA) ubiquitin ligase architecture, targeting, and activation. Cell 147: 1024–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N, Hayashi-Nishino M, Fukumoto H, Omori H, Yamamoto A, Noda T, Yoshimori T (2008) An Atg4B mutant hampers the lipidation of LC3 paralogues and causes defects in autophagosome closure. Mol Biol Cell 19: 4651–4659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburk SF, Wang QJ, Yue ZY (2010) The Beclin 1-VPS34 complex—at the crossroads of autophagy and beyond. Trends Cell Biol 20: 355–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya T, Kim M, Lipinski M, Li JY, Kim D, Lu T, Shen Y, Rameh L, Yankner B, Tsai LH, Yuan JY (2010) Negative regulation of Vps34 by Cdk mediated phosphorylation. Mol Cell 38: 500–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TS, Billadeau DD (2009) A FAM21-containing WASH complex regulates retromer-dependent sorting. Dev Cell 17: 699–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N (2008) Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Complexes with Mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell 19: 5360–5372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Mizushima N (2011) p62 targeting to the autophagosome formation site requires self-oligomerization but not LC3 binding. J Cell Biol 192: 17–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Gomez TS, Metlagel Z, Umetani J, Otwinowski Z, Rosen MK, Billadeau DD (2010) WASH and WAVE actin regulators of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) family are controlled by analogous structurally related complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10442–10447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JP, Arias EE, Chen J, Harper JW, Walter JC (2006) A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol Cell 23: 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Uero T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T (2000) LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 19: 5720–5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T (2001) Beclin-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep 2: 330–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N (2004) The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432: 1032–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Yu WH, Kumar A, Lee S, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Wolfe DM, Martinez-Vicente M, Massey AC, Sovak G, Uchiyama Y, Westaway D, Cuervo AM, Nixon RA (2010) Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require Presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 141: 1146–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li FF, Lan Y, Wang YL, Wang J, Yang GA, Meng FW, Han H, Meng AM, Wang YP, Yang XA (2011) Endothelial Smad4 maintains cerebrovascular integrity by activating N-Cadherin through cooperation with Notch. Dev Cell 20: 291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH, Jung JU (2006) Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol 8: 688–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardopoulou EV, Parghi SS, Friedman C, Osborn GE, Parkhurst SM, Trask BJ (2007) Human subtelomeric WASH genes encode a new subclass of the WASP family. PLoS Genet 3: 2477–2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen GH, Chen HY, Bray K, Reddy A, Bhanot G, Gelinas C, DiPaola RS, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E (2009) Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell 137: 1062–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, Omori H, Satoh T, Kurotori N, Maejima I, Shirahama-Noda K, Ichimura T, Isobe T, Akira S, Noda T, Yoshimori T (2009) Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nat Cell Biol 11: 385–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Tavshanjian B, Oleksy A, Perisic O, Houseman BT, Shokat KM, Williams RL (2010) Shaping development of autophagy inhibitors with the structure of the lipid kinase Vps34. Science 327: 1638–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Komatsu M (2011) Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147: 728–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monfregola J, Napolitano G, D'Urso M, Lappalainen P, Ursini MV (2010) Functional characterization of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein and Scar Homolog (WASH), a bi-modular nucleation-promoting factor able to interact with Biogenesis of Lysosome-related Organelle Subunit 2 (BLOS2) and gamma-Tubulin. J Biol Chem 285: 16951–16957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y (2009) Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 458–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu XP, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, Packer M, Schneider MD, Levine B (2005) Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122: 927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platta HW, Abrahamsen H, Thoresen SB, Stenmark H (2012) Nedd4-dependent lysine-11-linked polyubiquitination of the tumour suppressor Beclin 1. Biochem J 441: 399–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proikas-Cezanne T, Ruckerbauer S, Stierhof YD, Berg C, Nordheim A (2007) Human WIPI-1 puncta-formation: A novel assay to assess mammalian autophagy. Febs Lett 581: 3396–3404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi CS, Kehrl JH (2010) TRAF6 and A20 regulate lysine 63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin-1 to control TLR4-induced autophagy. Sci Signal 3: ra42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T, Klionsky DJ (2004) Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science 306: 990–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Powell DW, Rane MJ, Millard TH, Trent JO, Pierce WM, Klein JB, Machesky LM, McLeish KR (2003) Identification of the p16-Arc subunit of the Arp 2/3 complex as a substrate of MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 by proteomic analysis. J Biol Chem 278: 36410–36417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y, Liang C, Jung JU, Cheng JQ, Mule JJ, Pledger WJ, Wang HG (2007) Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1142–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjelle TE, Brech A, Juvet LK, Griffiths G, Berg T (1996) Isolation and characterization of early endosomes, late endosomes and terminal lysosomes: their role in protein degradation. J Cell Sci 109: 2905–2914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidberg H, Shvets E, Elazar Z (2011) Biogenesis and cargo selectivity of autophagosomes. Annu Rev Biochem 80: 125–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz IE, O'Rourke KM, Zhang ZM, Dornan D, Arnott D, Deshaies RJ, Dixit VM (2004) Human De-etiolated-1 regulates c-Jun by assembling a CUL4A ubiquitin ligase. Science 303: 1371–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Alva A, Su H, Dutt P, Freundt E, Welsh S, Baehrecke EH, Lenardo MJ (2004) Regulation of an ATG7-beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science 304: 1500–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, McPhee CK, Zheng LX, Mardones GA, Rong YG, Peng JY, Mi N, Zhao Y, Liu ZH, Wan FY, Hailey DW, Oorschot V, Klumperman J, Baehrecke EH, Lenardo MJ (2010) Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature 465: 942–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue ZY, Jin SK, Yang CW, Levine AJ, Heintz N (2003) Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15077–15082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Mizrachy L, Idelchuk Y, Koren I, Eisenstein M, Sabanay H, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Kimchi A (2009) DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-X-L and induction of autophagy. Embo Rep 10: 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng XH, Overmeyer JH, Maltese WA (2006) Functional specificity of the mammalian Beclin-Vps34 Pl 3-kinase complex in macroautophagy versus endocytosis and lysosomal enzyme trafficking. J Cell Sci 119: 259–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao TB, Zhang HL, Guo YM, Fan ZS (2007) Granzyme K directly processes bid to release cytochrome c and endonuclease g leading to mitochondria-dependent cell death. J Biol Chem 282: 12104–12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li XT, Yan Y, Backer JM, Chait BT, Heintz N, Yue ZY (2009) Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nat Cell Biol 11: 468–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.